6.6 COPD

Pathophysiology

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is a chronic, progressive, and incurable respiratory condition that causes breathing difficulties and reduced lung function. COPD is characterized by the obstruction of airflow in and out of the lungs. The primary cause of COPD is cigarette smoking. A deficiency of Alpha 1 antitrypsin, an enzyme with lung protective properties, is also a potential cause of COPD. Other causes of COPD include prolonged exposure to irritants that damage the lungs, such as environmental exposures, including air pollution, dust, chemicals, or secondhand smoke.[1]

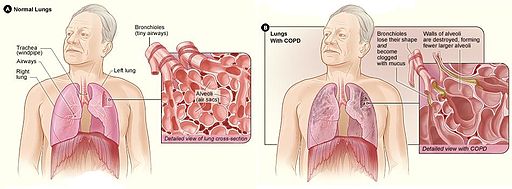

COPD includes two conditions called chronic bronchitis and emphysema. Chronic bronchitis is an inflammation of the bronchi and bronchioles characterized by increased mucus and chronic productive cough for at least three months of the year for at least two consecutive years. Emphysema is a destructive problem of lung elastic tissue that reduces its ability to recoil after stretching, leading to hyperinflation of the lung.

Most people who have COPD have a mixture of both emphysema and chronic bronchitis in different proportions, and the seriousness of each condition varies from person to person. In COPD, there is less air flow in and out of the airways because of one or more reasons[2]:

- The airways and alveoli lose their elastic quality.

- The walls between many of the air sacs are destroyed.

- The walls of the airways become thick and inflamed.

- The airways make more mucus than usual and can become clogged.

COPD is a progressive disease, meaning that symptoms worsen over time. In the early stages of COPD, individuals may not experience noticeable symptoms, but as the condition advances, breathing difficulties become more pronounced. Although there is no cure, treatments and lifestyle changes such as quitting smoking can help clients feel better, stay more active, and slow the progress of the disease. Oxygen therapy, pulmonary rehabilitation, and medications are prescribed to manage symptoms and enhance quality of life. Individuals with advanced COPD may require palliative and/or hospice care services.[3] See Figure 6.22[4] for an illustration of COPD.

Common Signs and Symptoms of COPD

Common signs and symptoms of COPD include the following[5]:

- Dyspnea, especially with physical activity. Clients may report breathing takes more effort or they are gasping for air.

- Fatigue due to reduced oxygenation of the body’s tissues and muscles.

- An ongoing cough or a cough that produces a lot of mucus, sometimes called a smoker’s cough. This is often the first symptom of COPD. However, they are not always strong enough to cough up the mucus due to the associated fatigue.

- Audible wheezing (i.e., a whistling or squeaky sound when breathing).

- Chest tightness or heaviness. Clients may report it is hard to take a deep breath or it’s painful to breathe.

- Nail clubbing from chronic hypoxia.

- Barrel chest due to hyperinflated alveoli

Acid-Base Balance

Because of the changes that occur in the bronchioles/alveoli and the air trapping that occurs in clients with COPD, the ability to inhale oxygen and exhale carbon dioxide is affected. It is common for clients with moderate to severe COPD to have ABG results with lower levels of dissolved oxygen in the blood (PaO2) and higher levels of dissolved carbon dioxide in the blood (PaCO2). As carbon dioxide is retained in the body, clients with COPD often develop chronic compensated respiratory acidosis as the kidneys compensate and retain bicarbonate to neutralize the acidic pH.[6]

Clients with acute exacerbations of COPD may develop uncompensated respiratory acidosis as gas exchange worsens. For this reason, ABGs are a common diagnostic test for clients hospitalized with a COPD exacerbation. Acute exacerbations of COPD are further discussed in the following subsection.

Review information about ABG analysis and respiratory acidosis in the “Acid-Base Balance” section in the “Fluids and Electrolytes” chapter in Open RN Nursing Fundamentals, 2e.

Acute Exacerbations of COPD

In addition to chronic symptoms of COPD that worsen over time, clients can also experience acute exacerbations of COPD. Environmental triggers and respiratory infections can lead to a sudden worsening of symptoms called a COPD exacerbation. During a COPD exacerbation, clients have worsening dyspnea and oxygen saturation levels lower than their baseline. If associated with a respiratory infection, they may also have a fever, increased chest tightness, worsening cough, and purulent sputum. Acute exacerbations often require hospitalization, so rapid recognition of these symptoms and notification of the health care provider are vital.

Clients with acute exacerbations of COPD undergo additional diagnostic testing, such as a chest X-ray, complete blood count (with a focus on WBCs), and ABG. Read more about these diagnostic tests in the “General Respiratory System Assessment and Interventions” section. ABG results may indicate uncompensated respiratory acidosis as the PaCO2 levels increase and the kidneys are no longer able to compensate for the retained CO2. ABG results help guide medical treatment.

Inhaled or oral steroids and additional bronchodilators may be prescribed. Antibiotics may be prescribed when a respiratory bacterial infection is suspected or confirmed. Severe symptoms may require hospitalization. Intravenous corticosteroids may be prescribed, along with noninvasive positive pressure ventilation, commonly referred to as CPAP or BiPAP. In very severe cases, intubation and mechanical ventilation may be required.

Oxygen Therapy

Long-term oxygen therapy (LTOT) is prescribed for clients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) when oxygen saturation levels are 88% or less when at rest and in a stable clinical condition. Research indicates that LTOT improves survival benefits and quality of life for clients with COPD with chronic hypoxemia. Other positive outcomes include decreased depression, improved cognitive function, improved exercise capacity, and decreased hospital admission rates.[7] Respiratory therapists typically assist clients in setting up LTOT, establish the oxygenation device and oxygen flow rates, and provide health teaching about its safe use in the home. Nurses reinforce this information on discharge and during follow-up visits.

Read additional information about oxygen equipment and safety measures in the “Oxygen Therapy” chapter of Open RN Nursing Skills, 2e.

Clients with COPD may be prescribed supplementary oxygen therapy during acute exacerbations of COPD or for long-term therapy. When administering oxygen to a client with COPD, it is important to understand how their respiratory drive differs from people who do not have COPD. As previously discussed in the “Review of Anatomy and Physiology of the Respiratory System” section of this chapter, an individual’s respiratory drive is primarily based on the level of carbon dioxide in their bloodstream. As carbon dioxide levels increase, the brain stimulates faster respiratory rates.

Clients with COPD chronically retain carbon dioxide, and their body’s response to high PaCO2 levels to stimulate breathing becomes blunted. Instead of relying on PaCO2 levels to initiate breathing, their brains primarily rely on dissolved oxygen levels in the bloodstream, referred to as hypoxic drive. For this reason, supplementary oxygen must be administered carefully to clients with COPD. Administering high-flow oxygen to a COPD client could potentially suppress their drive to breathe and cause a decreased respiratory rate, leading to additional carbon dioxide retention. To ensure the safe administration of supplemental oxygen to clients with COPD, it is crucial to follow these guidelines[8]:

- Aim for their prescribed target oxygen saturation level (usually between 88-92%).

- Provide oxygen at a low-flow rate, typically no more than 2-3 liters unless otherwise prescribed, to prevent the suppression of the client’s hypoxic drive.

- Continuously monitor the client’s pulse oximetry level, respiratory rate, and clinical condition. Titrate oxygen therapy to maintain the targeted oxygen saturation range while simultaneously avoiding suppression of their hypoxic drive to breathe.

COPD and Right-Sided Heart Failure

Clients with severe COPD may develop right-sided heart failure called cor pulmonale. As the right ventricle has to work harder to pump blood into the lungs that are hyperinflated, the cardiac muscle may enlarge and become less efficient.[9]

Review information about right-sided heart failure in the “Heart Failure” section of the “Cardiovascular Alterations” chapter.

Assessment

Clinical manifestations of COPD often develop as a result of reduced lung function. As with any chronic illness, it is vital for the nurse to be aware of a client’s baseline status to recognize signs of clinical deterioration requiring health care provider notification. See Table 6.6 for a summary of common manifestations of COPD across body systems.

Table 6.6. Clinical Manifestations of COPD[10],[11]

| Body System | Clinical Manifestations of COPD |

|---|---|

| Respiratory | Chronic cough, excessive sputum production, wheezing, dyspnea, reduced activity tolerance, barrel chest, adventitious lung sounds such as wheezing and rhonchi (coarse crackles), and frequent respiratory infections |

| Cardiovascular | Right-sided heart failure (Cor pulmonale) increases capillary refill time |

| Gastrointestinal | Decreased appetite and difficulty eating due to shortness of breath |

| Musculoskeletal | Reduced muscle strength or muscle wasting |

| Psychological & Emotional Well-Being | Anxiety and depression, reduced quality of life, and social isolation |

| Integumentary | Clubbing of the fingers and decreased skin turgor |

| Neurological | New onset confusion or change in level of consciousness if hypoxia or hypercapnia is present |

| General Symptoms | Fatigue or weakness |

Diagnostic Testing

The primary diagnostic test for COPD is spirometry. Spirometry can detect COPD even before symptoms are recognized. Spirometry test results determine the severity of COPD and are used to set treatment goals. Read more about spirometry testing under “Pulmonary Function Tests” in the General Respiratory System Assessment and Interventions” section of this chapter.

Clients with chronic COPD may also exhibit elevated levels of red blood cells, hemoglobin (Hgb), and hematocrit (HCT) as a compensatory response to chronic hypoxemia, which stimulates the production of red blood cells to carry more oxygen. This is referred to as secondary polycythemia.

Clients who are hospitalized for an acute COPD exacerbation have additional diagnostic testing performed, such as ABG, sputum samples, and chest X-rays.

- Arterial Blood Gas (ABG): As discussed earlier in this chapter, clients with stable, chronic COPD are often in a continual state of compensated respiratory acidosis due to carbon dioxide retention. However, clients experiencing an acute exacerbation of COPD often have ABG results indicating hypoxemia (low PaO2) and worsening hypercapnia (high PaCO2), resulting in uncompensated respiratory acidosis.

- Sputum Samples: Sputum samples may be obtained if an upper respiratory infection is suspected. These samples can help identify the presence of infection or other respiratory conditions.

- Chest X-ray: A chest X-ray may be obtained to assess for pneumonia. In clients with advanced COPD, the lungs may appear hyperinflated due to the destruction of alveolar walls and the trapping of air. The diaphragm may appear lower and flattened as a result of increased lung volume and hyperinflation. The weakened diaphragm has difficulty contracting effectively.

Review normal reference ranges for common diagnostic tests in “Appendix A – Normal Reference Ranges.”

Nursing Diagnoses

Nursing priorities for clients with COPD focus on improving respiratory function, enhancing quality of life, and promoting self-management.

Nursing diagnoses for clients with COPD are formulated based on the client’s assessment data, medical history, and specific needs. These nursing diagnoses guide the development of individualized care plans and interventions. Common nursing diagnoses are as follows[12]:

- Decreased Activity Tolerance

- Ineffective Airway Clearance

- Impaired gas exchange

- Anxiety

- Imbalanced Nutrition: Less Than Body Requirements

- Powerlessness

- Impaired Social Interaction

- Readiness for Enhanced Health Self-Management

Outcome Identification

Outcome identification includes setting short- and long-term goals and creating expected outcome statements customized for the client’s specific needs. Expected outcomes are statements of measurable action for the client within a specific time frame that are responsive to nursing interventions.

Sample expected outcomes for common nursing diagnoses related to COPD include the following:

- The client will maintain a patent airway as evidenced by clear breath sounds and absence of wheezing or crackles.

- The client will maintain oxygen saturation within the specified target range (i.e., 88-92%).

- The client will report increased ability to perform daily activities without excessive fatigue or dyspnea.

- The client will achieve and maintain an appropriate body weight and body mass index (BMI) for their age and height.

- The client will participate in support groups with other individuals with COPD.

Interventions

Medical Interventions

The primary intervention for clients with COPD who smoke is smoking cessation. Other medical interventions for COPD aim to achieve effective symptom control, improve lung function, prevent exacerbations, and enhance the client’s quality of life. These interventions are prescribed by health care providers based on the client’s COPD severity and their individualized needs.

Smoking Cessation

The chemicals in cigarettes, e-cigarettes, and cigars can damage the lungs and cause worsening symptoms, increase the risk of exacerbations, and decrease lung function. Continued smoking can also make lungs unresponsive to COPD medications.

Read more information about smoking cessation on the American Lung Association’s Quit Smoking web page.

Medication Therapy

Common medications prescribed for COPD are as follows[13],[14],[15]:

- Bronchodilators: Short-acting beta-agonists (SABAs) and long-acting beta-agonists (LABAs) help relax airway muscles, improving airflow. Anticholinergic bronchodilators reduce bronchoconstriction and mucus production.

- Short-acting Beta-Agonists (SABAs): SABAs relieve symptomatic bronchoconstriction and improve airflow. They provide quick relief of symptoms. Albuterol is a Beta-2 agonist that relaxes the smooth muscle of bronchioles, producing bronchodilation. Ipratropium is an anticholinergic that blocks the action of acetylcholine in the smooth muscle of the bronchioles, causing bronchodilation.

- Long-acting Beta-Agonists (LABAs): LABAs, like salmeterol, work as long-acting bronchodilators to maintain airway patency over an extended period. They are used as maintenance therapy for clients with moderate to severe COPD to reduce symptoms and exacerbations by promoting bronchodilation throughout the day.

- Inhaled Corticosteroids (ICS): ICS, like fluticasone, reduce and control inflammation in the airways and lung tissues.

- Corticosteroids: Some clients with severe COPD, or those experiencing an acute exacerbation of COPD, require oral corticosteroids, like prednisone, to systemically reduce airway inflammation and suppress the immune response. Clients who are hospitalized for an acute exacerbation of COPD may be prescribed intravenous corticosteroids, like methylprednisolone IV, to rapidly reduce the immune response.

- Mucolytics: Mucolytic agents, like oral guaifenesin, may be used to thin mucus, making it easier to clear sputum from the airways. Some clients with severe COPD may be prescribed acetylcysteine or dornase alfa that are administered via a nebulizer.

- Oxygen Therapy: Clients with severe COPD may be prescribed long-term oxygen therapy. Review the “Oxygen Therapy” discussion in the “Overview” subsection.

Read more information about medication classes used to treat COPD in the “Respiratory System” chapter of Open RN Nursing Pharmacology, 2e.

Immunizations

Clients diagnosed with COPD are encouraged to remain up-to-date on recommended vaccinations, including influenza, pneumococcal (pneumonia), respiratory syncytial virus (RSV), pertussis (Tdap), and COVID vaccines.

Review current information about “Recommended Vaccines By Age” from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).

Pulmonary Rehabilitation

Clients with COPD are often referred for pulmonary rehabilitation. Pulmonary rehabilitation is a supervised program that includes exercise training, health education, and breathing techniques for people who have chronic lung conditions like COPD.[16]

Read additional information about pulmonary rehabilitation on the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute’s “Pulmonary Rehabilitation” web page.

Surgery

Surgery is usually a last resort for people with COPD who have severe symptoms that have not improved from medication therapy. Potential surgeries for severe COPD include the following[17],[18]:

- Bullectomy: In a bullectomy, one or more very large bullae are removed from the lungs. Bullae are larger air spaces that form when the walls of the air sacs are destroyed. These air spaces can become so large that they interfere with breathing.

- Implantation of One-way Endobronchial Valves: Valves may be implanted in one of the bronchial tubes that allow air to exit the damaged parts of the lung, but not reenter.

- Lung Volume Reduction Surgery (LVRS): LVRS helps people with severe emphysema that affects the upper lung lobes. LVRS is not a cure for COPD but may improve exercise capacity and quality of life. The goal of the surgery is to remove about 30 percent of the most diseased lung tissue. While this reduces the size of the lungs, it also allows the remaining healthier part of the lungs to work better. LVRS also can help the diaphragm to return to its normal shape, allowing the person to breathe more efficiently and improve lung capacity.

- Lung Transplant: Lung transplant may be considered for individuals with advanced COPD who have not responded to other treatments. It may be considered if the client’s lung damage cannot be repaired; if the client has had three or more severe, acute exacerbations of COPD within the last year; or they are not a candidate for LVRS. The transplant team will evaluate the client to see if they are physically and emotionally healthy enough for a lung transplant. Important factors include being a nonsmoker and at a healthy weight. Clients who are deemed qualified to receive a lung transplant are placed on a waiting list to receive a single- or double-lung transplant. After surgery, the client will remain on immunosuppressive medications for the rest of their life.

Nursing Interventions

Nursing interventions for COPD are centered around improving respiratory function, managing symptoms, and enhancing the client’s quality of life. These interventions are designed to provide holistic care and support to individuals with COPD.

Medication Management

Nurses in all settings evaluate the effectiveness of the prescribed medication therapy for COPD and monitor for potential side effects. Clients are taught the purpose of prescribed medications, how to use the inhalers, their potential side effects, and when to notify the health care provider.

Dyspnea Management

The nurse continually monitors the client’s level of dyspnea and implements and teaches about strategies to manage dyspnea. For example, coughing and breathing techniques, positioning, and pursed-lip breathing are helpful techniques. The nurse also assists with other prescribed respiratory interventions, such as postural drainage, incentive spirometry, and vibratory pressure therapy. Postural drainage is a form of physical therapy where body fluids are drained from the lungs by working with gravity and changing position, along with chest percussion. Review information in the “General Respiratory System Assessment and Interventions” section earlier in this chapter.

Energy Management

Nurses teaching energy conservation techniques to clients with COPD to help them manage fatigue and activity intolerance.

Review energy management techniques in the “Anemia” section of the “Hematological Alterations” chapter.

Health Teaching

Nurses provide health teaching about several topics. If the client smokes, they are encouraged to stop smoking. Clients are taught about the COPD disease process and how to recognize symptoms of acute exacerbations that require prompt notification of the health care provider. Breathing techniques, such as diaphragmatic breathing and pursed-lip breathing, are demonstrated, and the client is asked to perform a return demonstration to demonstrate understanding. Clients are also taught the importance of maintaining current vaccinations to prevent illness, such as influenza, COVID-19, and pneumococcal.

Healthy lifestyle choices such as balanced nutrition and regular physical activity are encouraged to maintain a healthy weight. Clients are also encouraged to maintain proper hydration to keep secretions thin and easily removed by coughing.

Psychosocial Support

COPD is a chronic, progressive, incurable illness. Clients may experience feelings of powerlessness and hopelessness as the disease progresses and their ability to participate in activities they normally enjoy becomes limited. Nurses advocate for medical treatments, home oxygen therapy, and pulmonary rehabilitation to help clients to optimally manage dyspnea and improve activity intolerance. Clients are encouraged to verbalize their feelings, and nurses therapeutically promote positive coping strategies to empower clients to effectively self-manage their chronic disease at home.

Evaluation

During the evaluation stage, nurses determine the effectiveness of nursing interventions for a specific client. The previously identified expected outcomes are reviewed to determine if they were met, partially met, or not met by the time frames indicated. If outcomes are not met or only partially met by the time frame indicated, the nursing care plan is revised. Evaluation should occur every time the nurse implements interventions with a client, reviews updated laboratory or diagnostic test results, or discusses the care plan with other members of the interprofessional team.

![]() RN Recap: COPD

RN Recap: COPD

View a brief YouTube video[19] overview of COPD:

- National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. (2024). What is COPD? National Institutes of Health. https://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health/copd ↵

- National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. (2024). What is COPD? National Institutes of Health. https://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health/copd ↵

- National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. (2024). What is COPD? National Institutes of Health. https://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health/copd ↵

- “Copd 2010Side.JPG” by National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute is licensed in the Public Domain. ↵

- National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. (2024). What is COPD? National Institutes of Health. https://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health/copd ↵

- Pahal, P., Hashmi, M. F., & Sharma, S. (2023). Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease Compensatory Measures. StatPearls [Internet]. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK525962/ ↵

- Shebl, E., Modi, P., & Cates, T. D. (2023). Home Oxygen Therapy. StatPearls [Internet]. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK532994/ ↵

- Pahal, P., Hashmi, M. F., & Sharma, S. (2023). Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease Compensatory Measures. StatPearls [Internet]. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK525962/ ↵

- Mooney, L., et al. (2021). Impact of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in patients with heart failure with preserved ejection fraction: Insights from PARAGON‐HF. Journal of the American Heart Association, 10(23), e021494. https://www.ahajournals.org/doi/10.1161/JAHA.121.021494#d1e3937 ↵

- King Han, M., Dransfield, M. T., & Martinez, F. J. (2023). Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: Diagnosis and staging. UpToDate. https://www.uptodate.com/ ↵

- Stoller, J. K. (2023). COPD exacerbations: Management. UpToDate. https://www.uptodate.com/ ↵

- Flynn Makic, M. B., & Martinez-Kratz, M. R. (2023). Ackley and Ladwig’s Nursing diagnosis handbook: An evidence-based guide to planning care (13th ed.). Elsevier. ↵

- American Lung Association. (2023). COPD causes and risk factors. https://www.lung.org/lung-health-diseases/lung-disease-lookup/copd/what-causes-copd ↵

- King Han, M., Dransfield, M. T., & Martinez, F. J. (2023). Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: Diagnosis and staging. UpToDate. https://www.uptodate.com/ ↵

- Stoller, J. K. (2023). COPD exacerbations: Management. UpToDate. https://www.uptodate.com/ ↵

- National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. (2024). What is COPD? National Institutes of Health. https://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health/copd ↵

- National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. (2024). What is COPD? National Institutes of Health. https://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health/copd ↵

- American Lung Association. (n.d.). Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. COPD. https://www.lung.org/lung-health-diseases/lung-disease-lookup/copd ↵

- Open RN Project. (2024, April 4). Health Alterations - Chapter 6 Respiratory - COPD [Video]. YouTube. CC BY-NC 4.0.https://youtu.be/VMT3dT82Xfg ↵

A chronic, progressive, and incurable respiratory condition that causes breathing difficulties and reduced lung function.

Whistling or squeaky sound when breathing.

Prescribed for clients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) when oxygen saturation levels are 88% or less when at rest and in a stable clinical condition.

Instead of relying on PaCO2 levels to initiate breathing, the brain primarily relies on dissolved oxygen levels in the bloodstream to initiate respiratory effort.

Right-sided heart failure.

A supervised program that includes exercise training, health education, and breathing techniques for people who have chronic lung conditions.

One or more very large bullae are removed from the lungs.