1.2 Leadership Skills

Leadership skills are critical in a professional nursing role. During their educational journey, nursing students and new nursing graduates cultivate leadership skills while learning how to make informed decisions requiring clinical judgment. They identify, respond, and learn from their mistakes and seek guidance and mentorship from other nurses. They effectively communicate and collaborate with members of the interprofessional team to advocate for holistic care and to improve client outcomes. Successful nurses continue to reflect on each client interaction throughout their career as an opportunity to learn and grow as a professional nurse and leader.

Making Informed Clinical Decisions

Making informed clinical decisions is a foundation of professional nursing practice that requires clinical judgment and demonstrates nursing leadership at the bedside. To use clinical judgment, nurses must integrate critical thinking, clinical expertise, problem-solving, ethical decision-making, and emotional intelligence:

- Critical Thinking: Critical thinking is the ability to gather and evaluate relevant information, consider different perspectives, and make reasoned judgments. Critical thinking skills are reflected in the nurse’s ability to assess a client’s condition, identify risks and complications, and make adjustments to the nursing plan of care.

- Clinical Expertise: Clinical expertise is the aggregation of clinical knowledge that is foundational for making informed nursing decisions. Clinical expertise includes knowledge of evidence-based nursing practice, clinical guidelines, standards of practice, and technology advancements. Clinical expertise is reflected by the nurse’s ability to accurately analyze information, understand the connection to the client’s condition, and make informed decisions.

- Problem-Solving: Effective leaders in nursing excel in problem-solving. They approach challenges with a systematic and analytical mindset, seeking innovative solutions to improve client outcomes. Problem-solving involves identifying underlying causes of problems, generating alternative strategies, evaluating potential risks and benefits, and implementing effective interventions.

- Ethical Decision-Making: Nursing leadership requires the ability to make ethical decisions that prioritize the well-being and autonomy of clients. Nurses must navigate complex ethical dilemmas, balancing principles such as beneficence, autonomy, justice, and non-maleficence.

- Emotional Intelligence: Leadership in nursing involves emotional intelligence, which is the ability to understand and manage one’s own emotions and empathize with others. Nurses with high emotional intelligence can navigate challenging situations with empathy, respect, and effective communication.

Identifying, Responding, and Learning from Mistakes

The ability to identify, take ownership, and learn from one’s mistakes is a critical part of one’s nursing leadership role. Although all nurses strive to prevent errors, it is unrealistic to believe that as humans, our nursing practice will be without mistakes. At some point, every nurse will make an error, and it is critical that errors are acknowledged, addressed, and new strategies incorporated to avoid future errors. Strong leaders humbly acknowledge their errors to demonstrate that mistakes can and will occur, no matter one’s position or expertise. Sharing errors builds a “culture of safety” work environment in which the emphasis is on ownership and learning from errors rather than penalty.

A culture of safety is an organizational culture that embraces error reporting by employees with the goal of identifying systemic causes of problems that can be addressed to improve client safety. According to The Joint Commission, a culture of safety includes the following components[1]:

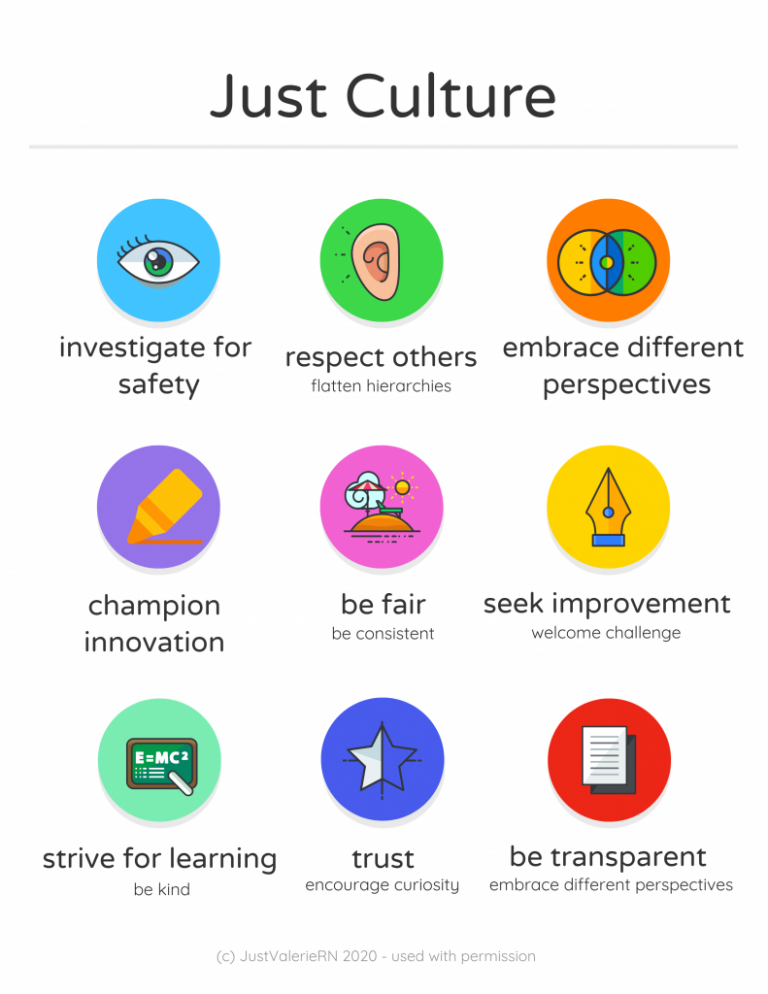

- Just Culture: A Just Culture is where people feel safe raising questions and concerns and reporting safety events in an environment that emphasizes a nonpunitive response to errors and near misses. Clear lines are drawn by managers between human error, at-risk, and reckless employee behaviors. See Figure 1.1[2] for an illustration of Just Culture.

- Reporting Culture: People realize errors are inevitable and are encouraged to speak up for client safety by reporting errors and near misses. For example, nurses complete an “incident report” according to agency policy when a medication error occurs or a client falls. Error reporting helps the agency manage risk and reduce potential liability.

- Learning Culture: People regularly collect information and learn from errors and successes while openly sharing data and information and applying best evidence to improve work processes and client outcomes.

Seeking Guidance and Mentorship

Mentorship has a significant impact on the professional development of nurses’ leadership skills. Mentorship is critical for knowledge transfer, skill development, career advancement, and personal growth.

Knowledge Transfer

Mentoring allows experienced and knowledgeable nurses to share their expertise, insights, and practical wisdom with less experienced nurses. This knowledge transfer is invaluable for developing clinical skills, enhancing critical thinking abilities, and gaining a deeper understanding of the complexities of nursing practice. Mentors provide guidance, answer questions, and offer real-world perspectives that textbooks and classroom education alone cannot provide.

Skill Development

A mentor acts as a role model and helps mentees develop a wide range of skills necessary for nursing leadership. This includes communication skills, decision-making abilities, conflict resolution techniques, and interpersonal skills. By observing and learning from their mentors, nurses can refine their own leadership capabilities, which, in turn, enhances their effectiveness in clinical decision-making, teamwork, and client care.

Career Advancement

A mentor can provide valuable guidance and support in navigating the various career pathways and opportunities within nursing. They can help mentees set goals, identify strengths and areas for improvement, and create personalized development plans.

Personal Growth

Mentorship extends beyond professional development and encompasses personal growth as well. Mentors can offer emotional support, encouragement, and advice on work-life balance, self-care, and managing stress. They can serve as a sounding board for challenges and help mentees build resilience and confidence in their abilities. The mentor-mentee relationship fosters a safe and nurturing environment where mentees can seek guidance, reflect on their experiences, and develop a strong professional identity.

Collaborating and Communicating

As advocates for quality, holistic care for their clients, all nurses demonstrate leadership skills while collaborating and communicating with health care team members, including other nurses, physicians, therapists, pharmacists, and other staff. Effective communication skills are essential to ensure the accurate exchange of information and to facilitate collaborative decision-making while also advocating for holistic care and quality client outcomes. Nurse leaders utilize standardized communication tools such as ISBARR, articulate their clinical assessments and rationales clearly, listen actively to others, and foster an open and respectful environment for team communication.

ISBARR

A common format used by health care team members to exchange client information is ISBARR, a mnemonic for the components of Introduction, Situation, Background, Assessment, Request/Recommendations, and Repeat back.[3],[4]

- Introduction: Introduce your name, role, and the agency from which you are calling.

- Situation: Provide the client’s name and location, the reason you are calling, recent vital signs, and the status of the client.

- Background: Provide pertinent background information about the client such as admitting medical diagnoses, code status, recent relevant lab or diagnostic results, and allergies.

- Assessment: Share abnormal assessment findings and your evaluation of the current client situation.

- Request/Recommendations: State what you would like the provider to do, such as reassess the client, order a lab/diagnostic test, prescribe/change medication, etc.

- Repeat back: If you are receiving new orders from a provider, repeat them to confirm accuracy. Be sure to document communication with the provider in the client’s chart.

Before using ISBARR to call a provider regarding a changing client condition or concern, it is important for nurses to prepare and gather appropriate information. See the following box for considerations when calling the provider.

Communication Guidelines for Nurses[5]

- Have I assessed this client before I call?

- Have I reviewed the current orders?

- Are there related standing orders or protocols?

- Have I read the most recent provider and nursing progress notes?

- Have I discussed concerns with my charge nurse, if necessary?

- When ready to call, have the following information on hand:

- Admitting diagnosis and date of admission

- Code status

- Allergies

- Most recent vital signs

- Most recent lab results

- Current meds and IV fluids

- If receiving oxygen therapy, current device and L/min

- Before calling, reflect on what you expect to happen as a result of this call and if you have any recommendations or specific requests.

- Repeat back any new orders to confirm them.

- Immediately after the call, document with whom you spoke, the exact time of the call, and a summary of the information shared and received.

Read an example of an ISBARR report in the following box.

Sample ISBARR Report From a Nurse to a Health Care Provider

I: “Hello Dr. Smith, this is Jane Murphy, RN from the Med-Surg unit.”

S: “I am calling to tell you about Ms. White in Room 210, who is experiencing an increase in pain, as well as redness at her incision site. Her recent vital signs were BP 160/95, heart rate 90, respiratory rate 22, O2 sat 96% on room air, and temperature 38 degrees Celsius. She is stable but her pain is worsening.”

B: “Ms. White is a 65-year-old female, admitted yesterday post hip surgical replacement. She has been rating her pain at 3 or 4 out of 10 since surgery with her scheduled medication, but now she is rating the pain as a 7, with no relief from her scheduled medication of Vicodin 5/325 mg administered an hour ago. She is scheduled for physical therapy later this morning and is stating she won’t be able to participate because of the pain this morning.”

A: “I just assessed the surgical site, and her dressing was clean, dry, and intact, but there is 4 cm redness surrounding the incision, and it is warm and tender to the touch. There is moderate serosanguinous drainage. Her lungs are clear, and her heart rate is regular. She has no allergies. I think she has developed a wound infection.”

R: “I am calling to request an order for a CBC, a wound culture, and increased dose of pain medication.”

R: “I am repeating back the order to confirm that you are ordering a STAT CBC and an increase of her Vicodin to 10/325 mg.”

View or print an ISBARR reference card.

Handoff Reports

Handoff reports are defined by The Joint Commission as “a transfer and acceptance of client care responsibility achieved through effective communication. It is a real-time process of passing client specific information from one caregiver to another, or from one team of caregivers to another, for the purpose of ensuring the continuity and safety of the client’s care.”[6] In 2017 The Joint Commission issued a sentinel alert about inadequate handoff communication that has resulted in client harm such as wrong-site surgeries, delays in treatment, falls, and medication errors.[7]

The Joint Commission encourages the standardization of critical content to be communicated by interprofessional team members during a handoff report both verbally (preferably face to face) and in written form. Critical content to communicate to the receiver in a handoff report includes the following components[8]:

- Sender contact information

- Illness assessment, including severity

- Client summary, including events leading up to illness or admission, hospital course, ongoing assessment, and plan of care

- To-do action list

- Contingency plans

- Allergy list

- Code status

- Medication list

- Recent laboratory tests

- Recent vital signs

Several strategies for improving handoff communication have been implemented nationally, such as the Bedside Handoff Report Checklist, closed-loop communication, and I-PASS.

Bedside Handoff Report Checklist

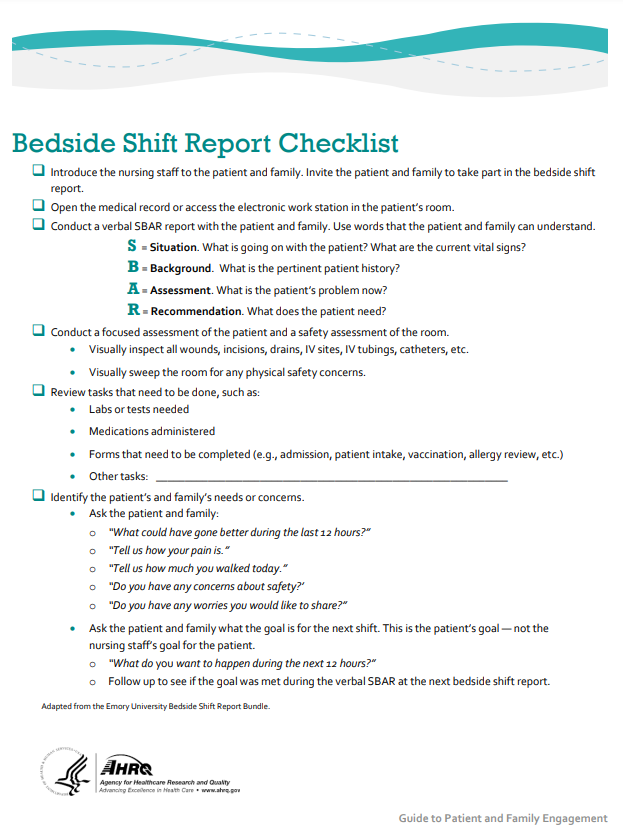

See Figure 1.2[9] for an example of the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality’s (AHRQ) Bedside Handoff Report Checklist to improve nursing handoff reports.[10] Although a bedside handoff report is similar to an ISBARR report, it contains additional information to ensure continuity of care across nursing shifts.

Print a copy of the AHRQ Bedside Shift Report Checklist PDF.[11]

View a supplementary YouTube video[12] for bedside handoff report: Mastery Level Bedside Shift Report.

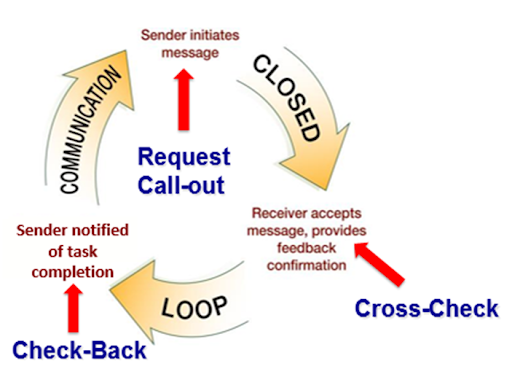

Closed-Loop Communication

The closed-loop communication strategy is used to ensure that information conveyed by the sender is heard by the receiver and completed. Closed-loop communication is especially important during emergency situations when verbal orders are being provided as treatments are immediately implemented. See Figure 1.3[13] for an illustration of closed-loop communication.

During closed loop communication, the following actions occur:

- The sender initiates the message.

- The receiver accepts the message and repeats back the message to confirm it (i.e., “Cross-Check”).

- The sender confirms the message.

- The receiver notified the sender the task was completed (i.e., “Check-Back”).

See an example of closed-loop communication during an emergent situation in the following box.

Closed-Loop Communication Example

Doctor: “Administer Benadryl 50 mg PO STAT.”

Nurse: “Give the resident Donna Smith Benadryl 50 mg PO STAT?”

Doctor: “That’s correct.”

(A few minutes later) Nurse: “Benadryl 50 mg PO given at 1125 to Donna Smith.”

I-PASS

I-PASS is a mnemonic used to provide structured communication among interprofessional team members. I-PASS stands for the following components[14]:

I: Illness severity

P: Patient summary

A: Action list

S: Situation awareness and contingency plans

S: Synthesis by receiver (i.e., closed-loop communication)

See a sample I-PASS handoff in Table 1.2.[15]

Table 1.2. Sample I-PASS Verbal Handoff[16]

| I | Illness Severity | This is our sickest patient on the unit, and he’s a full code. |

|---|---|---|

| P | Patient Summary | AJ is a 4-year-old boy admitted with hypoxia and respiratory distress secondary to left lower lobe pneumonia. He presented with cough and high fevers for two days before admission, and on the day of admission to the emergency department, he had worsening respiratory distress. In the emergency department, he was found to have a sodium level of 130 mg/dL likely due to volume depletion. He received a fluid bolus, and oxygen administration was started at 2.5 L/min per nasal cannula. He is on ceftriaxone. |

| A | Action List | Assess him at midnight to ensure his vital signs are stable. Check to determine if his blood culture is positive tonight. |

| S | Situations Awareness & Contingency Planning | If his respiratory distress worsens, get another chest radiograph to determine if he is developing an effusion. |

| S | Synthesis by Receiver | Ok, so AJ is a 4-year-old admitted with hypoxia and respiratory distress secondary to a left lower lobe pneumonia receiving ceftriaxone, oxygen, and fluids. I will assess him at midnight to ensure he is stable and check on his blood culture. If his respiratory status worsens, I will repeat a radiograph to look for an effusion. |

Read additional information about the roles and responsibilities of interprofessional team members in “Health Care Settings & Team” in Open RN Nursing Fundamentals, 2e.

Documentation

Accurate, timely, concise, and thorough documentation by nurses ensures continuity of care for their clients. It is well-known by health care team members that in a court of law the rule of thumb is, “If it wasn’t documented, it wasn’t done.” Any type of documentation in the electronic health record (EHR) is considered a legal document. Abbreviations should be avoided in legal documentation, and some abbreviations are prohibited. See a list of error prone abbreviations in the box below.

Read the current list of error-prone abbreviations by the Institute of Safe Medication Practices. These abbreviations should never be used when communicating medical information verbally, electronically, and/or in handwritten applications. Abbreviations included on The Joint Commission’s “Do Not Use” list are identified with a double asterisk (**) and must be included on an organization’s “Do Not Use” list.

Nursing staff access the electronic health record (EHR) to help ensure accuracy in medication administration and document the medication administration to help ensure client safety. See Figure 1.4[17] for an image of a nurse accessing a client’s EHR.

Electronic Health Record

The electronic health record (EHR) contains the following important information:

- History and Physical (H&P): A history and physical (H&P) is a specific type of documentation created by the health care provider when the client is admitted to the facility. An H&P includes important information about the client’s current status, medical history, and the treatment plan in a concise format that is helpful for the nurse to review. Information typically includes the reason for admission, health history, surgical history, allergies, current medications, physical examination findings, medical diagnoses, and the treatment plan.

- Provider orders: This section includes the prescriptions, or medical orders, that the nurse must legally implement or appropriately communicate according to agency policy if not implemented.

- Medication Administration Records (MARs): Medications are charted through electronic medication administration records (MARs). These records interface the medication orders from providers with pharmacists and are also the location where nurses document medications administered.

- Treatment Administration Records (TARs): In many facilities, treatments are documented on a treatment administration record.

- Laboratory results: This section includes results from blood work and other tests performed in the lab.

- Diagnostic test results: This section includes results from diagnostic tests ordered by the provider such as X-rays, ultrasounds, etc.

- Progress notes: This section contains notes created by nurses, providers, and other interprofessional team members regarding client care. It is helpful for the nurse to review daily progress notes by all team members to ensure continuity of care.

- Nursing care plans: Nursing care plans are created by registered nurses (RNs). Documentation of individualized nursing care plans is legally required in long-term care facilities by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) and in hospitals by The Joint Commission. Nursing care plans are individualized to meet the specific and unique needs of each client. They contain expected outcomes and planned interventions to be completed by nurses and other members of the interprofessional team. As part of the nursing process, nurses routinely evaluate the client’s progress toward meeting the expected outcomes and modify the nursing care plan as needed. Read more about nursing care plans in the “Planning” section of the “Nursing Process” chapter in Open RN Nursing Fundamentals, 2e.

Read the American Nurses Association’s Principles for Nursing Documentation PDF.

Learning From Client Interactions

Every client interaction provides the nursing student and nurse an opportunity to grow and develop as a leader. Client interaction provides the opportunity to enhance one’s clinical skills by applying knowledge and expertise, improving critical thinking and clinical judgment, and enhancing communication skills. After each client interaction, the nursing student and nurse can self-reflect on the interaction, identify areas for improvement, and set goals for professional development. Nurse leaders who embrace this continuous learning mindset can help to advance the profession and foster a culture of lifelong learning that is critical for addressing the complexities of today’s health care environment.

- The Joint Commission. (2021). The essential role of leadership in developing a safety culture. Sentinel Event Alert 57. https://www.jointcommission.org/resources/sentinel-event/sentinel-event-alert-newsletters/sentinel-event-alert-57-the-essential-role-of-leadership-in-developing-a-safety-culture/ ↵

- “Just Culture Infographic.png” by Valeria Palarski 2020. Used with permission. ↵

- Institute for Healthcare Improvement. (n.d.). SBAR tool. https://www.ihi.org/resources/tools/sbar-tool-situation-background-assessment-recommendation ↵

- Grbach, W., Vincent, L., & Struth, D. (n.d.). Reformulating SBAR to "I-SBAR-R". Quality and Safety Education for Nurses. https://www.qsen.org/strategies-submission/reformulating-sbar-to-%22i-sbar-r%22 ↵

- Patient Safety and Quality: An Evidence-Based Handbook for Nurses is in the public domain. ↵

- Starmer, A. J., Spector, N. D., Srivastava, R., Allen, A. D., Landrigan, C. P., Sectish, T. C., & I-Pass Study Group. (2012). Transforming pediatric GME. Pediatrics, 129(2), 201-204. https://www.ipassinstitute.com/hubfs/I-PASS-mnemonic.pdf ↵

- The Joint Commission. (2021). The essential role of leadership in developing a safety culture. Sentinel Event Alert 57. https://www.jointcommission.org/resources/sentinel-event/sentinel-event-alert-newsletters/sentinel-event-alert-57-the-essential-role-of-leadership-in-developing-a-safety-culture/ ↵

- The Joint Commission. (2021). The essential role of leadership in developing a safety culture. Sentinel Event Alert 57. https://www.jointcommission.org/resources/sentinel-event/sentinel-event-alert-newsletters/sentinel-event-alert-57-the-essential-role-of-leadership-in-developing-a-safety-culture/ ↵

- “Bedside Shift Report Checklist” by AHRQ is in the public domain. ↵

- “Bedside Shift Report Checklist” by AHRQ is in the public domain. ↵

- “Bedside Shift Report Checklist” by AHRQ is in the public domain. ↵

- UP Health System. (2016, December 22). Mastery level bedside shift report [Video]. YouTube. All rights reserved. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=RHpbuljThoc ↵

- Image is derivative of “close-loop.png” by unknown and is licensed under CC0. Access for free at https://www.ahrq.gov/teamstepps/instructor/essentials/pocketguide.html ↵

- The Joint Commission. (2017). Inadequate hand-off communication. Sentinel Event Alert 58. https://www.jointcommission.org/resources/patient-safety-topics/sentinel-event/sentinel-event-alert-newsletters/sentinel-event-alert-58-inadequate-hand-off-communication/ ↵

- Starmer, A. J., Spector, N. D., Srivastava, R., Allen, A. D., Landrigan, C. P., Sectish, T. C., & I-Pass Study Group. (2012). Transforming pediatric GME. Pediatrics, 129(2), 201-204. https://www.ipassinstitute.com/hubfs/I-PASS-mnemonic.pdf ↵

- Starmer, A. J., Spector, N. D., Srivastava, R., Allen, A. D., Landrigan, C. P., Sectish, T. C., & I-Pass Study Group. (2012). Transforming pediatric GME. Pediatrics, 129(2), 201-204. https://www.ipassinstitute.com/hubfs/I-PASS-mnemonic.pdf ↵

- “Winn_Army_Community_Hospital_Pharmacy_Stays_Online_During_Power_Outage.jpg” by Flickr user MC4 Army is licensed under CC BY 2.0 ↵

An organizational culture that embraces error reporting by employees with the goal of identifying systemic causes of problems that can be addressed to improve client safety

A mnemonic for the components of Introduction, Situation, Background, Assessment, Request/Recommendations, and Repeat back

A transfer and acceptance of patient care responsibility achieved through effective communication

Similar to an ISBARR report but contains additional information to ensure continuity of care across nursing shifts.

Strategy is used to ensure that information conveyed by the sender is heard by the receiver and completed

A mnemonic used to provide structured communication among interprofessional team members with a focus on illness severity, patient summary, action list, situation awareness, and synthesis.