11.2 Review of Anatomy & Physiology of the Gastrointestinal System

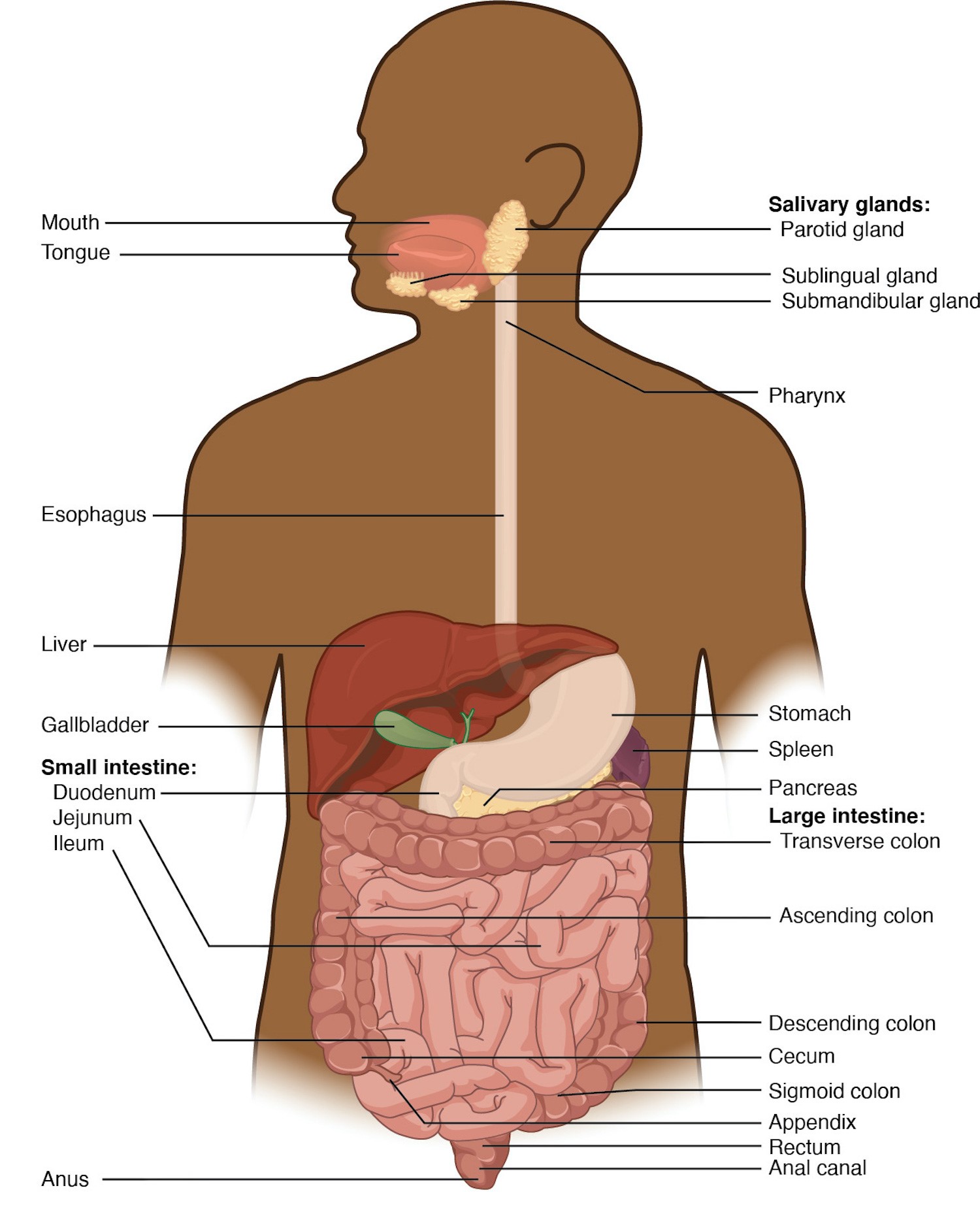

This section will review the anatomy and physiology of the gastrointestinal system, including the mouth, tongue, salivary glands, pharynx, esophagus, stomach, small intestine, and large intestine, as well as the accessory organs of the liver, pancreas, and gallbladder. See Figure 11.1[1] for an illustration of gastrointestinal system organs.

Anatomy

Mouth

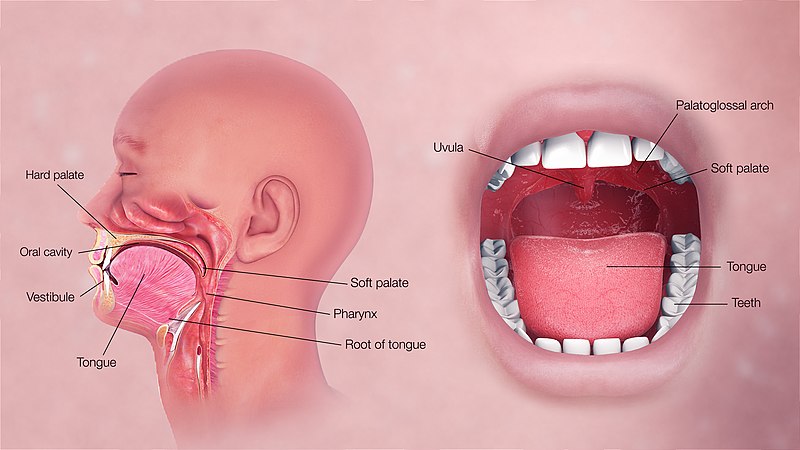

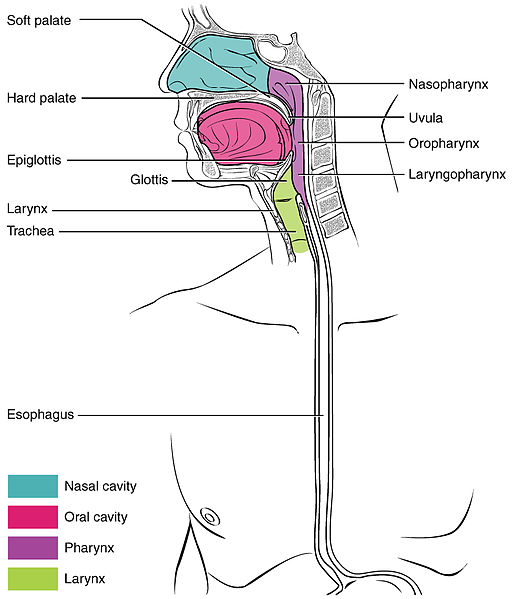

The mouth, cheeks, tongue, and palate form the oral cavity. See Figure 11.2[2] for an illustration of the oral cavity. If you run your tongue along the roof of your mouth, you’ll notice the roof of the mouth has an arch called a hard palate. The anterior region of the palate serves as a septum (i.e., wall) between the oral and nasal cavities, as well as a rigid shelf against which the tongue can push food when swallowing. The hard palate ends in the posterior oral cavity where the tissue becomes fleshier. This part of the palate, known as the soft palate, is composed mainly of skeletal muscle that can be manipulated for actions like swallowing or singing.[3]

A fleshy extension of tissue called the uvula drops down from the center of the soft palate. When swallowing, the soft palate and uvula move upward, helping to keep foods and liquid from entering the nasal cavity and respiratory tract.[4]

Two muscular folds extend downward from the soft palate on either side of the uvula. Between these two folds are the palatine tonsils, clusters of lymphoid tissue that protect the pharynx. The lingual tonsils are located at the base of the tongue.[5]

Tongue

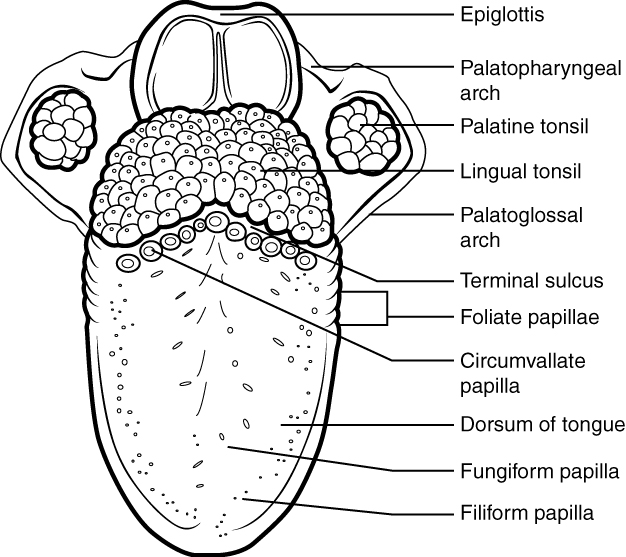

The tongue facilitates ingestion, digestion, sensation (of taste, texture, and temperature of food), swallowing, and vocalization. It has a mucous membrane covering and is composed of skeletal muscles that facilitate eating, swallowing, and speaking. The top and sides of the tongue are studded with papillae and taste buds to facilitate sensation. Lingual glands secrete mucus and a watery fluid that contains the enzyme lipase, which plays an initial role in breaking down food before it reaches the stomach.[6] See Figure 11.3[7] for an illustration of the papillae on the tongue.

Salivary Glands

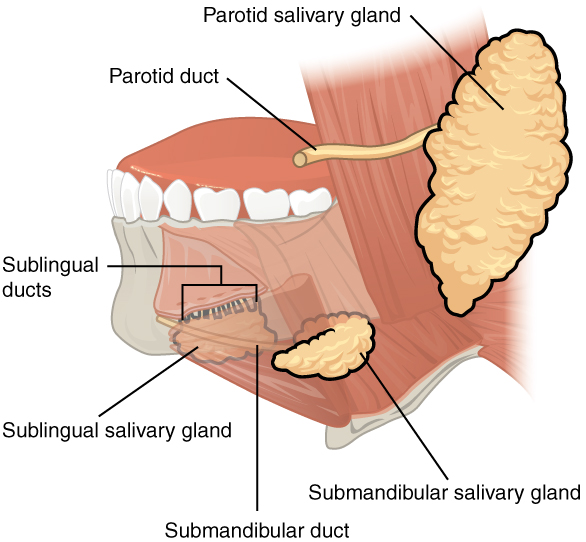

Many small salivary glands are housed within the mucous membranes of the mouth and tongue that are constantly secreting saliva into the oral cavity or indirectly through salivary ducts. Saliva moistens the mouth and teeth and increases when eating to moisten food and initiate the chemical breakdown of carbohydrates and fats.[8] See Figure 11.4[9] for an illustration of the salivary glands.

Pharynx

The pharynx, commonly called the throat, is a tube of muscle lined with a mucous membrane that runs from the posterior oral and nasal cavities to the opening of the esophagus and larynx.[10] See Figure 11.5[11] for an illustration of the pharynx.

The pharynx has three subdivisions. The superior section, the nasopharynx, is involved only in breathing and speech. The other two subdivisions, the oropharynx and the laryngopharynx, are used for both breathing and digestion. The oropharynx begins inferior to the nasopharynx and continues to the laryngopharynx. The inferior border of the laryngopharynx connects to the esophagus, whereas the anterior portion connects to the larynx.[12]

The pharynx is involved in both digestion and breathing. It receives air from the mouth and nasal cavities and food from the mouth. When food enters the pharynx, involuntary muscle contractions close the epiglottis to prevent food from entering the larynx and trachea, and food enters the esophagus.[13]

Esophagus

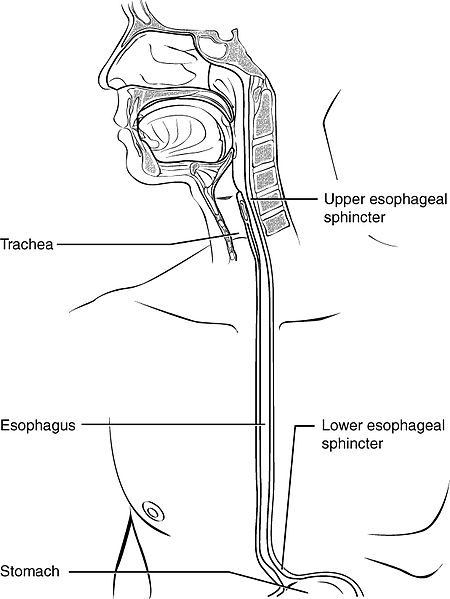

The esophagus is a muscular tube that connects the pharynx to the stomach. It is located posteriorly to the trachea and is approximately ten inches long. See Figure 11.6[14] for an illustration of the esophagus. The upper esophageal sphincter controls the movement of food from the pharynx to the esophagus. Recall that sphincters are muscles that surround tubes and serve as valves, closing the tube when the sphincters contract and opening it when they relax.[15]

The upper two thirds of the esophagus consist of muscles. A series of contractions called peristalsis push food through the esophagus and into the stomach. Just before the opening to the stomach is a ring-shaped muscle called the lower esophageal sphincter (LES). This sphincter opens to let food pass into the stomach and closes to keep it there.[16]

Stomach

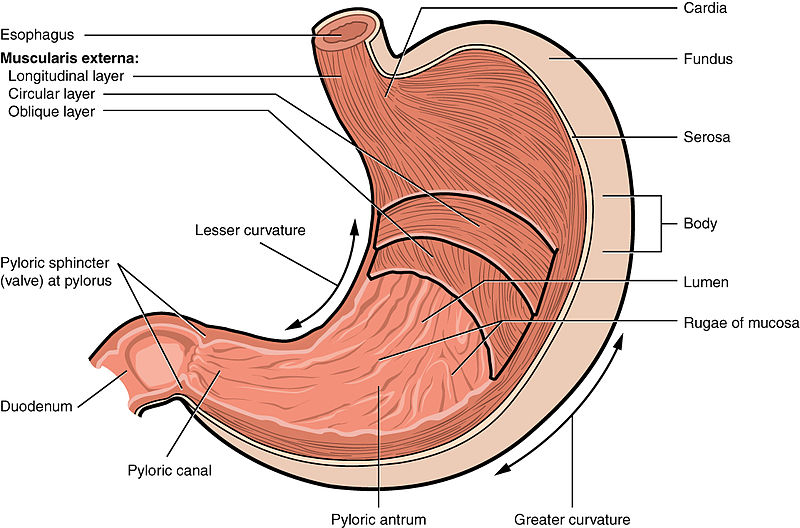

The stomach is a sac-like organ where food is mixed with gastric juice. There are four main regions in the stomach: the cardia, fundus, body, and pylorus. The funnel-shaped pylorus connects the stomach to the duodenum, the first part of the small intestine. The pyloric sphincter is located at this latter point of connection and controls stomach emptying into the small intestine.[17] See Figure 11.7[18] for an illustration of the stomach.

The inner lining of the stomach is covered by a mucous membrane that secretes a protective coat of alkaline mucus. The mucus protects the stomach from corrosive stomach acid. Gastric glands lie under the surface of this lining and secrete a complex digestive fluid referred to as gastric juice. Gastric juice consists of the following components: water, mucus, hydrochloric acid, pepsin, and intrinsic factor. The purpose of gastric juice is not only to help with the breakdown of food, but also to protect the client against infectious agents, which may be deterred by the acidic environment. Some of the components of gastric juice will be discussed in more detail below.[19]

Parietal cells and chief cells are found within the gastric glands. Parietal cells produce and secrete hydrochloric acid (HCl) to maintain the acidity of the environment with a pH of 1 to 4. Parietal cells also secrete a substance called intrinsic factor, which is necessary for the absorption of vitamin B12 in the small intestine. Parietal cells are the primary site of action for many drugs that treat acid-related disorders. Chief cells secrete pepsinogen that becomes pepsin when exposed to acid. Pepsin is a digestive enzyme that breaks down protein.[20],[21],[22],[23],[24]

The stomach also contains enteroendocrine cells (ECL or enterochromaffin-like cells) located in the gastric glands that secrete substances, including serotonin, histamine, and somatostatin. Serotonin, also known as 5-HT, aids in intestinal motility and nutrient absorption and also plays a role in gastrointestinal inflammation. Histamine and somatostatin help regulate the secretion of gastric acid. Histamine leads to the secretion of gastric acid by acting on parietal cells, and somatostatin inhibits parietal cells or histamine release to decrease gastric acid levels. Additionally, G cells in the stomach secrete gastrin that promotes secretions of digestive substances. Although all these cells play an important role in the digestive system, acid-related diseases, such as gastroesophageal reflux disease, can occur when there is an imbalance of secretions.[25],[26],[27],[28]

The muscular walls of the stomach move food through the stomach and vigorously churn it, mechanically breaking it down into smaller particles.

Small Intestine

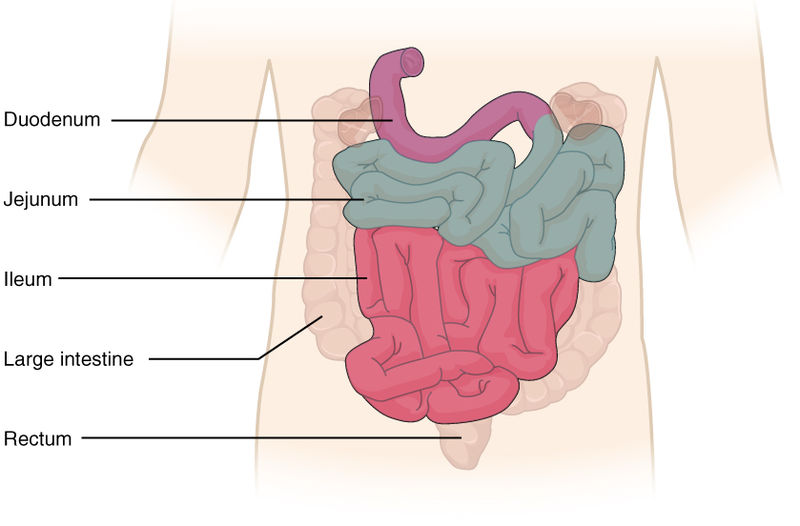

Partially digested food, called chyme, is released from the stomach via the pyloric sphincter and enters the small intestine, the part of the digestive tract where most of the digestion and absorption into the blood occurs. Approximately 90 percent of nutrients from food are absorbed through villi, small fingerlike extensions on the inner surface of the small intestine. The small intestine is about ten feet long. Its name derives from its small diameter of about one inch, compared to the large intestine’s diameter of about three inches.[29]

The coiled tube of the small intestine is subdivided into three regions called the duodenum, jejunum, and ileum. The ileum joins the cecum of the large intestine at the ileocecal sphincter. The ileocecal valve controls the flow of chyme from the small intestine to the large intestine.[30] See Figure 11.8[31] for an illustration of these regions.

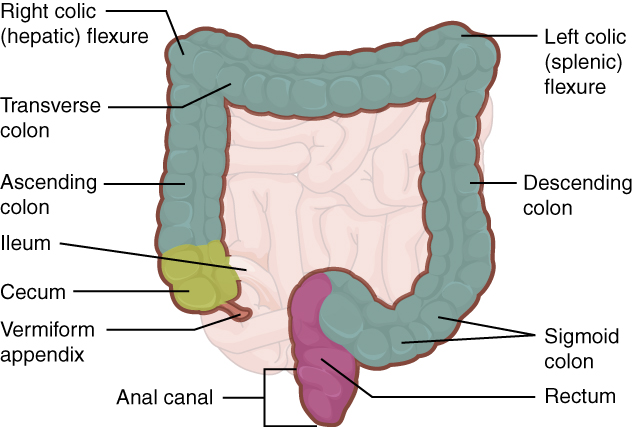

Large Intestine

The large intestine runs from the cecum to the anus. The primary functions of the large intestine are to finish absorption of nutrients and water, synthesize certain vitamins, and form and eliminate feces, also called stool. The large intestine is about one half the length of the small intestine but is called large because its diameter is three inches, about three times the diameter of the small intestine. The large intestine is subdivided into four main regions: the cecum, the colon, the rectum, and the anal canal. The colon is further subdivided into the ascending, transverse, descending, and sigmoid colon.[32] See Figure 11.9[33] for an illustration of the large intestine.

Cecum

The cecum is the initial part of the large intestine. It receives the contents of the small intestine and continues absorbing water and salts. The appendix is a small pouch attached to the end of the cecum. Its twisted anatomy provides a haven for the accumulation and multiplication of enteric bacteria that can lead to appendicitis.[34]

Colon

Food residue entering the colon travels up the ascending colon on the right side of the abdomen. At the inferior surface of the liver, the colon bends to become the transverse colon, where it travels across to the left side of the abdomen. From there, chyme passes through the descending colon, which runs down the left side of the posterior abdominal wall and becomes the S-shaped sigmoid colon.[35]

Rectum

The rectum is the final eight inches of the large intestine. It has three folds, called the rectal valves, that help separate feces from flatus, commonly referred to as gas.[36]

Anal Canal

The anal canal is about three inches long and opens to the exterior of the body at the anus, the end of the digestive tract. The anal canal includes two sphincters. The internal anal sphincter is made of smooth muscle, and its contractions are involuntary. The external anal sphincter is made of skeletal muscle, which is under voluntary control. Except when defecating, both sphincters usually remain closed.[37]

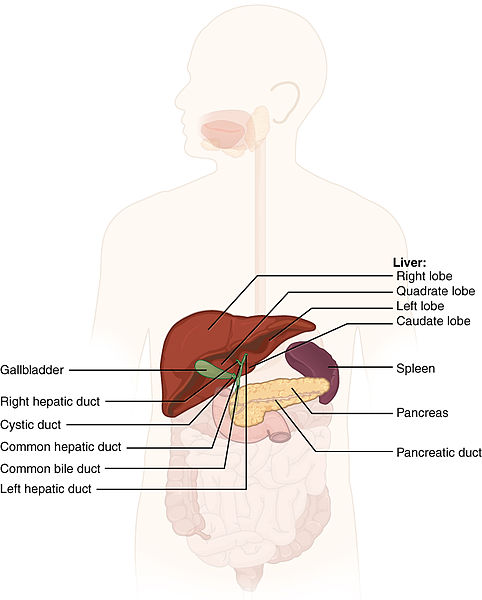

Accessory Organs of Digestion

Chemical digestion in the small intestine relies on the activities of three accessory digestive organs: the liver, pancreas, and gallbladder. See Figure 11.10[38] for an illustration of these accessory organs. The digestive role of the liver is to produce bile and export it to the duodenum. The gallbladder stores, concentrates, and releases bile. The pancreas produces pancreatic juice, which contains digestive enzymes and bicarbonate ions, and delivers it to the duodenum via the common bile duct.[39]

Figure 11.10 Accessory Organs: Liver, Pancreas, and Gallbladder

Liver

The liver weighs about three pounds in an adult. In addition to being an accessory digestive organ, it plays a number of roles in metabolism, blood clotting, protein creation, and cleansing the blood of toxins. The liver lies inferior to the diaphragm in the right upper quadrant of the abdominal cavity. It is protected by the surrounding ribs. The liver is divided into two primary lobes, a large right lobe and a much smaller left lobe.[40]

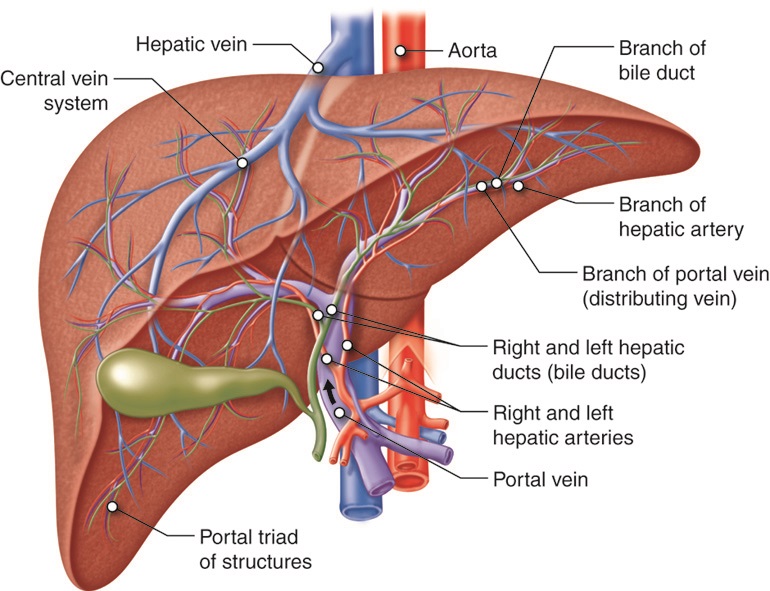

Hepatic Portal Circulation

The portal vein delivers nutrient-rich blood from the small intestine to the liver. This blood contains nutrients, toxins, and medications that are absorbed and metabolized by the liver. The hepatic artery also delivers oxygenated blood from the heart to the liver. After the liver processes the blood and metabolizes nutrients and toxins, it releases blood through the hepatic vein into the inferior vena cava. This is referred to as hepatic portal circulation.[41] See Figure 11.11[42] for an illustration of hepatic portal circulation.

Bile

Proteins, iron, and bilirubin are transported in the blood to the liver. In the liver, proteins and iron are recycled, whereas bilirubin is excreted in the bile. Bilirubin, a yellowish pigment produced by the breakdown of red blood cells, gives bile its color. Bile is a digestive fluid produced and secreted by the liver that breaks down lipids in the small intestine. Bilirubin is eventually transformed by intestinal bacteria into a brown pigment that gives stool its characteristic color.

In some diseases, bile does not enter the intestine, resulting in white stool with a high fat content because virtually no fats are broken down by the bile. Steatorrhea refers to fatty stool.[43]

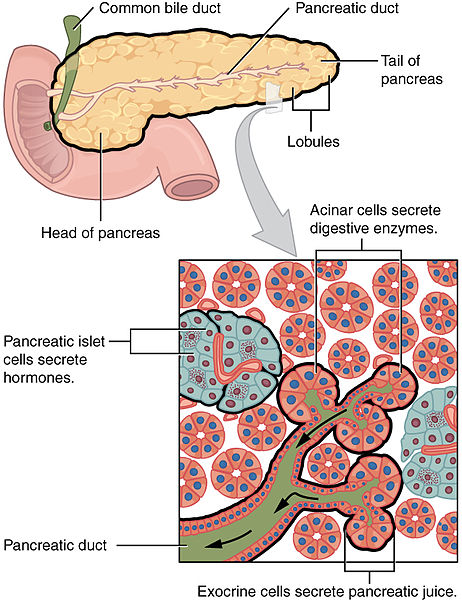

Pancreas

The soft, oblong, glandular pancreas lies transversely in the retroperitoneum behind the stomach. The pancreas has two functions referred to as exocrine, meaning secreting digestive enzymes, and endocrine, meaning releasing hormones into the blood.[44]

The pancreas produces protein-digesting enzymes in their inactive forms that are activated in the duodenum so they don’t attack the pancreas. Enzymes that don’t attack the pancreas are secreted in their active forms, such as amylase that digests carbohydrates and lipase that digests fat. The pancreas delivers this pancreatic juice to the duodenum through the common bile duct (carrying bile from the liver and gallbladder) just before entering the duodenum. The pancreatic islet cells secrete hormones such as insulin and glucagon.[45] See Figure 11.12[46] for an illustration of the pancreas.

For more information on the hormone functions of the pancreas, view the “Endocrine Alterations” chapter.

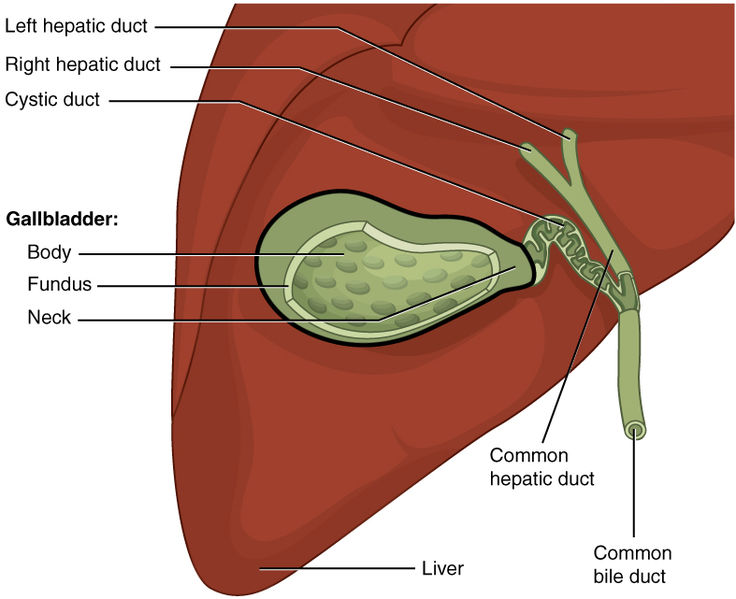

Gallbladder

The gallbladder is about three to four inches long and is nested in a shallow area on the posterior aspect of the right lobe of the liver. This muscular sac stores, concentrates, and propels bile into the duodenum via the common bile duct.[47] See Figure 11.13[48] for an illustration of the gallbladder.

Physiology of the Digestive System

The main functions of the digestive system are ingesting food, digesting food, absorbing nutrients, and eliminating waste products.[49] See Table 11.2 for an overview of the functions of the organs of the digestive tract.

Table 11.2. Functions of the Digestive Organs[50]

| Organ | Major Functions | Other Functions |

|---|---|---|

| Mouth | Ingests food

Chews and mixes food Begins chemical breakdown of carbohydrates via salivary amylase Moves food into the pharynx Begins breakdown of lipids via lingual lipase |

Moistens and dissolves food, allowing taste

Cleans and lubricates the teeth and oral cavity Promotes some antimicrobial activity |

| Pharynx | Propels food from the oral cavity to the esophagus | Lubricates food and passageways |

| Esophagus | Propels food to the stomach | Lubricates food and passageways |

| Stomach | Mixes and churns food with gastric juices to form chyme

Begins chemical breakdown of proteins Releases food into the duodenum as chyme Absorbs some fat-soluble substances Possesses antimicrobial functions |

Stimulates protein-digesting enzymes

Secretes intrinsic factor required for vitamin B12 absorption in small intestine |

| Small Intestine | Mixes chyme with digestive juices

Propels food at a rate slow enough for digestion and absorption Absorbs breakdown products of carbohydrates, proteins, lipids, and nucleic acids, along with vitamins, minerals, and water Performs physical digestion via segmentation, the mechanical mixing of food with digestive juices |

Provides optimal medium for enzymatic activity |

| Large Intestine | Further breaks down food residues

Absorbs most residual water, electrolytes, and vitamins produced by enteric bacteria Propels feces toward rectum Eliminates feces |

Food residue is concentrated and temporarily stored prior to defecation

Mucus eases passage of feces through colon |

| Accessory Organs | Liver produces bile salts, which emulsify lipids, aiding in their digestion and absorption

Gallbladder stores, concentrates, and releases bile Pancreas produces digestive enzymes and bicarbonate |

Bicarbonate-rich pancreatic juices help neutralize acidic chyme and provide optimal environment for enzymatic activity |

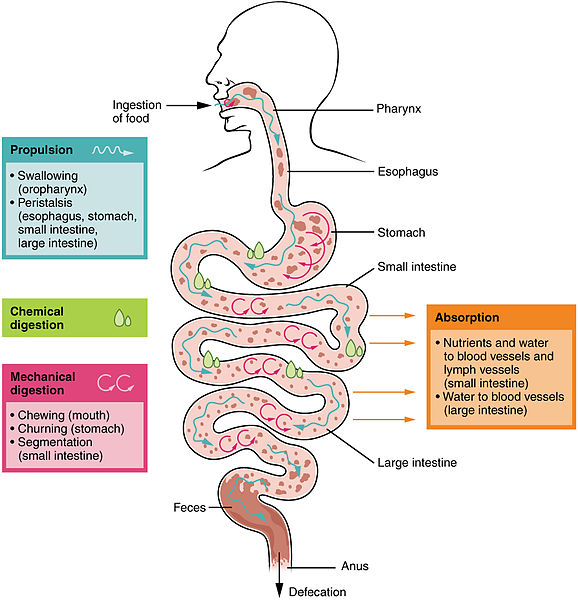

Digestive Processes

Digestive processes involve the interaction of several organs and occur gradually as food moves through the gastrointestinal tract. The processes of digestion include six activities: ingestion, propulsion, mechanical digestion, chemical digestion, absorption, and defecation.[51],[52],[53] See Figure 11.14[54] for an illustration of digestive processes.

Ingestion

Ingestion refers to the entry of food through the mouth where it is chewed and mixed with saliva. Saliva contains enzymes that begin breaking down the carbohydrates and fats in the food. Chewing produces a soft mass of food called a bolus that is an appropriate size for swallowing.[55],[56],[57]

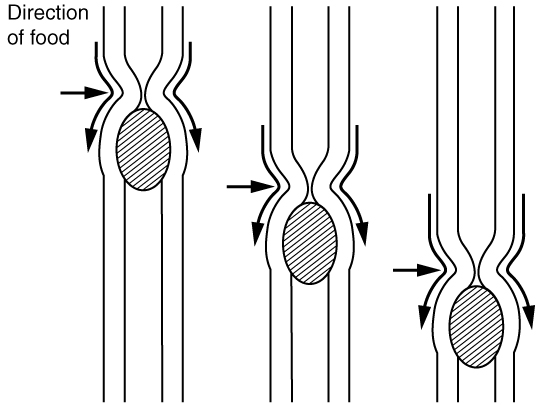

Propulsion

Food leaves the mouth when the tongue and pharyngeal muscles propel it into the esophagus. This act of swallowing is an example of propulsion, which refers to the movement of food through the digestive tract. It includes both the voluntary process of swallowing and the involuntary process of peristalsis. Peristalsis consists of sequential, alternating waves of contraction and relaxation of alimentary wall smooth muscles, which act to propel food. See Figure 11.15[58] for an illustration of peristalsis. Peristaltic waves also play a role in mixing food with digestive juices. Peristalsis is so powerful that swallowed foods and liquids enter the stomach even if you are standing on your head.[59],[60],[61]

Mechanical Digestion

Mechanical digestion is a physical process that does not change the chemical nature of the food but makes it smaller to increase its surface area and mobility. Mechanical digestion starts with chewing and then progresses to mechanical churning of food in the stomach. In the stomach, the bolus of food further breaks apart, allowing for more surface area to be exposed to the digestive juices of chemical digestion. Mechanical digestion also occurs in the small intestine, but to a lesser extent than what occurs in the stomach.[62],[63],[64]

Chemical Digestion

Chemical digestion begins in the mouth and is completed in the small intestine. Digestive secretions contain water, enzymes, acids, and salts that create an acidic “soup” that breaks down food molecules into their chemical building blocks. For example, proteins are broken down into amino acids.[65],[66],[67]

Absorption

Nutrients are substances that provide nourishment to cells. After food molecules have been broken down during chemical digestion, nutrients enter the bloodstream through the process of absorption. Absorption takes place primarily in the small intestine.[68],[69],[70]

Defecation

During defecation, the final step in digestion, undigested materials are removed from the body as feces. The process of defecation begins when mass movements, strong contractions that quickly move undigested materials, force feces from the colon into the rectum, stretching the rectal wall and provoking the defecation reflex, which eliminates feces from the rectum. This parasympathetic reflex is mediated by the spinal cord. It contracts the sigmoid colon and rectum, relaxes the internal anal sphincter, and initially contracts the external anal sphincter. Figure 11.16[71] reviews the anatomy of the rectum and its external and internal sphincters. The presence of feces in the anal canal sends a signal to the brain, which gives the person the choice of voluntarily opening the external anal sphincter (defecating) or keeping it temporarily closed. If defecation is delayed until a more convenient time, it takes a few seconds for the reflex contractions to stop and the rectal walls to relax. The next mass movement will trigger additional defecation reflexes until defecation occurs.[72],[73],[74]

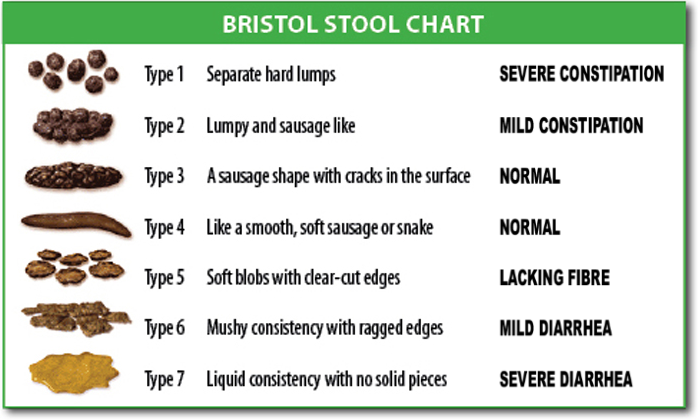

If defecation is delayed for an extended time, additional water is absorbed, making the feces firmer and potentially leading to constipation. Alternatively, if the waste matter moves too quickly through the intestines, not enough water is absorbed, and diarrhea can result. Figure 11.17[75] demonstrates the Bristol Stool Chart that is used to assess stool characteristics, ranging from very constipated to diarrhea.

Physiology of Nausea and Vomiting

Nausea and vomiting are common conditions experienced by clients. Nausea is the unpleasant sensation of having the urge to vomit, and vomiting (emesis) is the forceful oral expulsion of gastric contents.[76] There are many potential causes of nausea and vomiting, such as the following[77]:

- Morning sickness during pregnancy

- Gastroenteritis and other infections

- Migraines

- Motion sickness

- Food poisoning

- Side effects of medicines, including those for cancer chemotherapy

- GERD and ulcers

- Intestinal obstruction

- Poisoning or exposure to a toxic substance

- Diseases of other organs (cardiac, renal, or liver)

Nausea and vomiting are common and are usually not serious. However, the health care provider should be contacted immediately if the following conditions occur[78]:

- Vomiting for longer than 24 hours

- Blood in the vomit (hematemesis)

- Severe abdominal pain

- Severe headache and stiff neck

- Signs of dehydration, such as dry mouth, infrequent urination, or dark urine

Treatment of nausea and vomiting should be tailored to the cause. There are several medications that work on different neuroreceptors that can treat nausea and vomiting. For severe cases of vomiting, intravenous fluids may also be needed to treat the accompanying dehydration.[79],[80]

- “abe85277d60c52f85be133e1b5ddc40aea009e1c.jpg” by J. Gordon Betts, et al. is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/anatomy-and-physiology-2e/pages/23-1-overview-of-the-digestive-system ↵

- This image is a derivative of “3D_Medical_Animation_Oral_Cavity.jpg” by https://www.scientificanimations.com and is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0 ↵

- This work is a derivative of Medical Terminology 2e by Open RN and is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- This work is a derivative of Medical Terminology 2e by Open RN and is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- This work is a derivative of Medical Terminology 2e by Open RN and is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- This work is a derivative of Medical Terminology 2e by Open RN and is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- "2407_Tongue.jpg” by OpenStax College is licensed under CC BY 3.0 ↵

- This work is a derivative of Medical Terminology 2e by Open RN and is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- "2408_Salivary_Glands.jpg” by OpenStax College is licensed under CC BY 3.0 ↵

- This work is a derivative of Medical Terminology 2e by Open RN and is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- “2411_Pharynx.jpg” by OpenStax College is licensed under CC BY 3.0 ↵

- This work is a derivative of Medical Terminology 2e by Open RN and is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- This work is a derivative of Medical Terminology 2e by Open RN and is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- “2412_The_Esophagus.jpg” by OpenStax College is CC BY 3.0 ↵

- This work is a derivative of Medical Terminology 2e by Open RN and is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- This work is a derivative of Medical Terminology 2e by Open RN and is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- This work is a derivative of Medical Terminology 2e by Open RN and is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- “2414_Stomach.jpg” by OpenStax College is licensed under CC BY 3.0 ↵

- This work is a derivative of Medical Terminology 2e by Open RN and is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- This work is a derivative of Medical Terminology 2e by Open RN and is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- Physiology, Pepsin by Heda, Toro, & Tombazzi is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 ↵

- Physiology, Stomach by Hsu, Safadi, & Lui is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 ↵

- Latorre, R., Sternini, C., De Giorgio, R., & Greenwood-Van Meerveld, B. (2015). Enteroendocrine cells: A review of their role in brain-gut communication. Neurogastroenterology & Motility, 28(5), 620-630. https://doi.org/10.1111/nmo.12754 ↵

- The Role of Serotonin Neurotransmission in Gastrointestinal Tract and Pharmacotherapy by Guzel & Mirowska-Guzel is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- Physiology, Pepsin by Heda, Toro, & Tombazzi is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 ↵

- Physiology, Stomach by Hsu, Safadi, & Lui is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 ↵

- Latorre, R., Sternini, C., De Giorgio, R., & Greenwood-Van Meerveld, B. (2015). Enteroendocrine cells: A review of their role in brain-gut communication. Neurogastroenterology & Motility, 28(5), 620-630. https://doi.org/10.1111/nmo.12754 ↵

- The Role of Serotonin Neurotransmission in Gastrointestinal Tract and Pharmacotherapy by Guzel & Mirowska-Guzel is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- This work is a derivative of Medical Terminology 2e by Open RN and is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- This work is a derivative of Medical Terminology 2e by Open RN and is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- “2417_Small_IntestineN.jpg” by OpenStax College is licensed under CC BY 3.0 ↵

- This work is a derivative of Medical Terminology 2e by Open RN and is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- “2420_Large_Intestine.jpg” by OpenStax College is licensed under CC BY 3.0 ↵

- This work is a derivative of Medical Terminology 2e by Open RN and is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- This work is a derivative of Medical Terminology 2e by Open RN and is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- This work is a derivative of Medical Terminology 2e by Open RN and is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- This work is a derivative of Medical Terminology 2e by Open RN and is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- “2422_Accessory_Organs.jpg” by OpenStax College is licensed under CC BY 3.0 ↵

- This work is a derivative of Medical Terminology 2e by Open RN and is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- This work is a derivative of Medical Terminology 2e by Open RN and is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- This work is a derivative of Medical Terminology 2e by Open RN and is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- “Cenveo - Drawing Liver anatomy and vascularisation - English labels” by Cenveo is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- This work is a derivative of Medical Terminology 2e by Open RN and is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- This work is a derivative of Medical Terminology 2e by Open RN and is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- This work is a derivative of Medical Terminology 2e by Open RN and is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- “2424_Exocrine_and_Endocrine_Pancreas.jpg” by OpenStax College is licensed under CC BY 3.0 ↵

- This work is a derivative of Medical Terminology 2e by Open RN and is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- "2425_Gallbladder.jpg” by OpenStax College is licensed under CC BY 3.0 ↵

- This work is a derivative of Medical Terminology 2e by Open RN and is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- OpenStax. (2023). Anatomy & Physiology. https://openstax.org/books/anatomy-and-physiology/pages/23-2-digestive-system-processes-and-regulation ↵

- This work is a derivative of Medical Terminology 2e by Open RN and is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- Physiology, Digestion by Patricia & Dhamoon is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 ↵

- Physiology, Large Intestine by Azzouz & Sharma is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 ↵

- “2405_Digestive_Process.jpg” by OpenStax College is licensed under CC BY 3.0 ↵

- This work is a derivative of Medical Terminology 2e by Open RN and is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- Physiology, Digestion by Patricia & Dhamoon is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 ↵

- Physiology, Large Intestine by Azzouz & Sharma is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 ↵

- “2404_PeristalsisN.jpg” by OpenStax College is licensed under CC BY 3.0 ↵

- This work is a derivative of Medical Terminology 2e by Open RN and is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- Physiology, Digestion by Patricia & Dhamoon is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 ↵

- Physiology, Large Intestine by Azzouz & Sharma is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 ↵

- This work is a derivative of Medical Terminology 2e by Open RN and is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- Physiology, Digestion by Patricia & Dhamoon is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 ↵

- Physiology, Large Intestine by Azzouz & Sharma is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 ↵

- This work is a derivative of Medical Terminology 2e by Open RN and is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- Physiology, Digestion by Patricia & Dhamoon is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 ↵

- Physiology, Large Intestine by Azzouz & Sharma is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 ↵

- This work is a derivative of Medical Terminology 2e by Open RN and is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- Physiology, Digestion by Patricia & Dhamoon is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 ↵

- Physiology, Large Intestine by Azzouz & Sharma is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 ↵

- “Anorectum.gif” by U.S. Government, National Institutes of Health is licensed under CC0 ↵

- This work is a derivate of Nursing Pharmacology 2e by Open RN and is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- Physiology, Digestion by Patricia & Dhamoon is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 ↵

- Physiology, Large Intestine by Azzouz & Sharma is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 ↵

- “BristolStoolChart.png” by Cabot Health, Bristol Stool Chart is licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0 ↵

- Bashashati, M., & McCallum, R. (2014). Neurochemical mechanisms and pharmacologic strategies in managing nausea and vomiting related to cyclic vomiting syndrome and other gastrointestinal disorders. European Journal of Pharmacology, 772, 79. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejphar.2013.09.075 ↵

- This work is a derivate of Nursing Pharmacology 2e by Open RN and is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- This work is a derivate of Nursing Pharmacology 2e by Open RN and is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- MedlinePlus [Internet]. Bethesda (MD): National Library of Medicine (US); [updated 2019 October 23]. Nausea and vomiting; [updated 2019 February 7; reviewed 2016 March 17; cited 2019 October 27]. https://medlineplus.gov/nauseaandvomiting.html ↵

- Bashashati, M., & McCallum, R. (2014). Neurochemical mechanisms and pharmacologic strategies in managing nausea and vomiting related to cyclic vomiting syndrome and other gastrointestinal disorders. European Journal of Pharmacology, 772, 79. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejphar.2013.09.075 ↵

The mouth area, encompassing the lips, cheeks, palate, and floor of the mouth.

A fleshy extension at the back of the soft palate that hangs above the throat.

A muscular organ in the mouth, aiding in ingestion, digestion, sensation of food, swallowing, and speaking.

Small glands in the mucous membranes of the mouth and tongue that secrete saliva directly into the oral cavity or indirectly through salivary ducts.

Commonly known as the throat.

The muscular tube that conveys food and liquids from the throat to the stomach.

The involuntary constriction and relaxation of the muscles in the gastrointestinal system, creating wave-like movements that push food forward.

A sac-like organ of the digestive system where food is mixed with gastric juice.

A ring of smooth muscle at the end of the stomach, regulating the flow of partially digested food into the small intestine.

A digestive fluid secreted by the stomach, containing hydrochloric acid, pepsin, water, mucus, and intrinsic factor.

Cells found in the glands of the stomach that produce and secrete hydrochloric acid and intrinsic factor.

A protein produced by the parietal cells of the stomach that allows vitamin B12 to be absorbed by the intestines.

Cells in the glands of the stomach that secrete pepsinogen.

A digestive enzyme that breaks down protein; formed when pepsinogen is exposed to acid.

Partially digested food that passes from the stomach to the small intestine.

The part of the intestine where most of the digestion and absorption of food occurs, extending between the stomach and large intestine.

Small, finger-like projections that protrude from the epithelial lining of the intestinal wall, increasing the surface area for absorption.

The first section of the small intestine, immediately beyond the stomach, leading to the jejunum.

The part of the small intestine between the duodenum and ileum.

The third portion of the small intestine, between the jejunum and the cecum of the large intestine.

Controls the flow of chyme from the small intestine to the large intestine.

The last part of the digestive system that runs from the cecum to the anus; absorbs water and electrolytes; forms, stores, and eliminates feces.

Waste matter discharged from the bowels; also known as stool.

The first section of the large intestine into which the ileum opens.

A small pouch attached to the end of the cecum.

Inflammation of the appendix.

The first part of the colon that travels upward on the right side of the abdomen.

The middle part of the colon that travels across the abdomen.

The part of the colon that travels downward on the left side of the abdomen.

S-shaped are of the colon

The final section of the large intestine, terminating at the anus.

Gas in the gastrointestinal tract, expelled through the anus.

A 3-inch long section at the end of the gastrointestinal tract that opens to the exterior of the body at the anus.

The area that opens to the exterior of the body at the end of the digestive tract.

A large lobed organ in the abdomen, involved in digestion, metabolism, blood clotting, protein creation, and cleansing the blood of toxins.

A greenish-brown fluid that aids in digestion by breaking down lipids, secreted by the liver and stored in the gallbladder.

A yellowish pigment formed in the liver by the breakdown of red blood cells.

The excretion of abnormal quantities of fat with the feces.

A long, flat gland that lies behind the stomach which is responsible for endocrine and exocrine functions.

Refers to the release of digestive enzymes called amylase and lipase that help to digest food.

Relating to glands that secrete hormones or other products directly into the blood.

An enzyme, produced chiefly in the pancreas and salivary glands, that breaks down carbohydrates.

An enzyme that breaks down lipids (fats).

Digestive enzymes secreted by the pancreas and delivered to the duodenum.

A small organ where bile is stored and concentrated before it is released into the small intestine.

The mechanical mixing of food with digestive juices.

Vomiting blood.