6.5 Asthma

Overview

Asthma is a common chronic condition that affects the airways in the lungs. Individuals have different symptoms of asthma, with symptom severity ranging from “mild intermittent” symptoms to “severe persistent” symptoms. Asthma can be well-controlled by taking prescription medication and avoiding specific exposures that trigger an asthma attack.[1],[2]

Pathophysiology

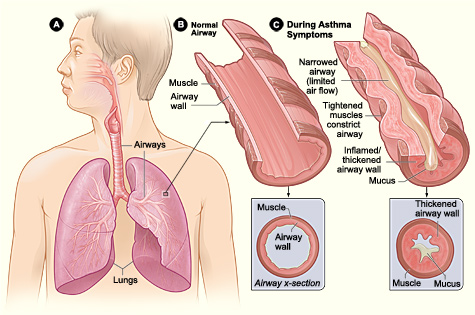

Asthma is caused by chronic inflammation in the airways, resulting in narrowed air passages. Individuals with asthma also experience bronchoconstriction that tightens the smooth muscle surrounding the airways, further limiting airflow.[3] When individuals with asthma are experiencing symptoms of bronchoconstriction and inflammation, they may also have increased mucus, further blocking their airways. See Figure 6.18[4] for an illustration of asthma symptoms.

Asthma causes repeated episodes of wheezing, dyspnea, chest tightness, and nighttime or early morning coughing. Between these episodes, many individuals with asthma are asymptomatic.[5]

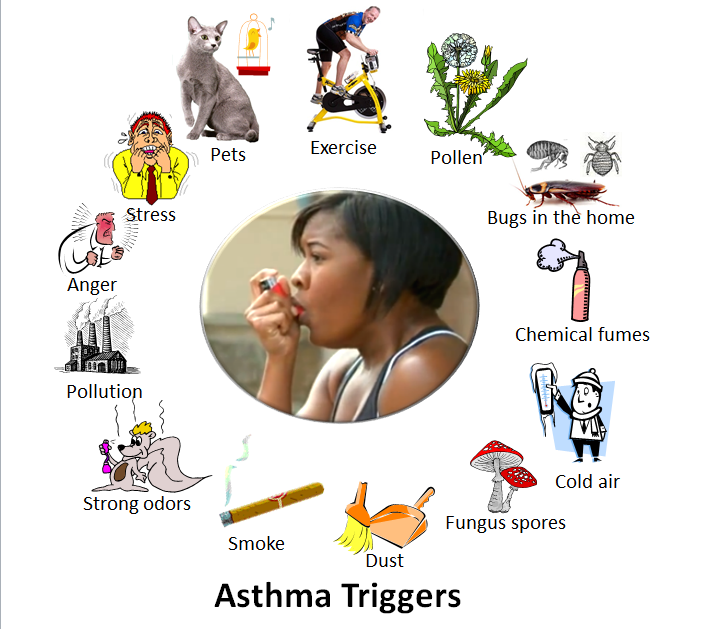

Asthma can occur at any age and can be triggered by a variety of causes such as allergens, exercise, tobacco smoke, air pollutants, gastroesophageal reflux disease, cold air, and extreme emotion.[6] See Figure 6.19[7] for an illustration of common asthma triggers. Nurses teach clients diagnosed with asthma to recognize their triggers and avoid them to prevent asthma attacks.

There are two major classes of medications used to control asthma, referred to as quick-relief and long-term control. Quick-relief inhalers like albuterol and ipratropium are used to control symptoms that occur during an asthma attack. Long-term control medicines help prevent asthma attacks, but they do not resolve symptoms that occur during an asthma attack.[8] Asthma medications are further discussed in the “Medical Interventions” subsection later in this section.

Status Asthmaticus

Status asthmaticus is a severe and life-threatening asthma attack that is unresponsive to standard treatments such as bronchodilators and corticosteroids. It is a medical emergency that requires immediate intervention, typically in an emergency department or by a medical response team.

Status asthmaticus is characterized by the following:

- Severe airway obstruction

- Rapid and labored breathing

- Worsening hypoxemia

- Decreased mental alertness

- Ineffective bronchodilator response

- Cyanosis

- Silent chest – minimal or no breath sounds heard on auscultation

- Exhaustion

Treatment for status asthmaticus typically involves the following[9],[10],[11]:

- Oxygen Therapy: Oxygen is administered to quickly resolve hypoxemia and improve oxygen levels in the blood.

- Systemic Corticosteroids: Corticosteroids (e.g., methylprednisolone) are administered intravenously to quickly reduce airway inflammation and swelling.

- Continuous Nebulized Bronchodilators: High-dose bronchodilators are continuously administered, such as albuterol via nebulization.

- Magnesium Sulfate: Intravenous magnesium sulfate may be administered to relax bronchial smooth muscles.

- Intubation and Mechanical Ventilation: In severe cases when hypoxia and hypercapnia are present, endotracheal intubation and mechanical ventilation may be necessary. This procedure is typically performed by respiratory therapists, paramedics, physicians, or anesthesiologists.

- Continuous Monitoring of Vital Signs and ECG: Continuous monitoring of vital signs and oxygen saturation levels and an electrocardiogram (ECG) are performed to closely monitor the client’s condition because the hypoxia can trigger arrhythmias.

Health Disparities Related to Asthma

The burden of asthma in the United States falls disproportionately on Black, Hispanic, and American Indian/Alaska Native people. These groups have the highest asthma rates, deaths, and hospitalizations. For example, when compared to White Americans, Black Americans are three times more likely to die from asthma.[12]

Racial and ethnic disparities in asthma are caused by complex factors, including these factors[13]:

- Social determinants such as socioeconomic status, education, neighborhood environment, employment, social support networks, and access to health care

- Structural determinants such as insurance and health care policies

- Biological determinants such as genetics

- Behavioral determinants such as tobacco use and adherence to prescribed medications

These strategies have been developed to improve asthma care in at risk populations[14]:

- Improving implementation of evidence-based guidelines, care, and treatments by expanding specialist care coverage, lowering copays, expanding eligibility criteria, and reducing barriers to treatment.

- Reducing exposure to pollution by strengthening clean air policies, reducing transportation-related emissions, restricting zoning of polluting sources, and transitioning to a clean energy economy.

- Providing personalized, culturally appropriate asthma action plans using the client’s and caregivers’ preferred language and learning styles (i.e., visual, audio, or kinesthetic).

- Improving trust in health care by engaging diverse clients, families, and community partners as early as possible when developing asthma prevention and care programs.

Read additional information in the full Asthma Disparities in America Report by the Allergy and Asthma Foundation of America.

Assessment

Clinical manifestations of asthma are related to the inflammation and bronchoconstriction that occur in the airways. Individuals with well-controlled asthma may exhibit few or no symptoms. Signs and symptoms of individuals with asthma that is not well-controlled are as follows[15]:

- Wheezing

- Dyspnea

- Chest tightness

- Nighttime or early morning coughing

- Awakening at night with asthma symptoms

Severity of signs and symptoms during asthma attacks are further discussed in the “Asthma Action Plan” section under “Medical Interventions.”

Diagnostic Testing

Diagnostic testing for asthma involves several clinical assessment and lung function tests such as the following[16],[17],[18]:

- Peak flow monitoring: Peak flow monitoring is used by clients with moderate to severe asthma to monitor and manage their asthma symptoms. It involves a handheld device called a peak flow meter that measures the rate of air that can be forcefully breathed out of the lungs. This measurement is called a peak expiratory flow rate (PEFR). A baseline PEFR is established for an individual diagnosed with asthma when their symptoms are well-controlled. Ranges of PEFRs are included on the client’s Asthma Action Plan to help determine if they are in the Green, Yellow, or Red Zone. See Figure 6.20[19] for an image of a peak flow meter. Additional information about teaching clients how to use a peak flow meter is discussed under “Health Teaching” in the “Nursing Interventions” subsection.

- Spirometry: Read more about spirometry in the “Diagnostic Testing” subsection of the “General Respiratory System Assessment and Interventions” section. Decreased FEV1 compared to normal reference ranges, as well as a significant increase in FEV1 after bronchodilator administration, indicates asthma.

- Methacholine Challenge: A methacholine challenge test is used when other tests are inconclusive for diagnosing asthma. Methacholine is a bronchoconstrictor that is inhaled to measure airway responsiveness.

- Allergen Testing: Allergen testing may be conducted to identify specific allergens that can trigger an individual’s asthma symptoms.

Nursing Problems and Diagnoses

Nursing priorities for clients with asthma involve addressing dyspnea and inadequate oxygenation, promoting self-management and positive coping, and managing anxiety that is associated with asthma attacks.

Nursing diagnoses for clients with asthma are formulated based on the client’s assessment data, medical history, and specific needs. These nursing diagnoses guide the development of individualized care plans and interventions.

Common NANDA nursing diagnoses include the following[20]:

- Ineffective Airway Clearance R/T bronchoconstriction and mucus

- Anxiety R/T dyspnea

- Readiness for Enhanced Health Self-Management

Outcome Identification

Outcome identification includes setting short- and long-term goals and creating expected outcome statements customized for the client’s specific needs. Expected outcomes are statements of measurable action for the client within a specific time frame that are responsive to nursing interventions.

Sample expected outcomes for individuals diagnosed with asthma are as follows:

- The client will demonstrate accurate use of their prescribed inhalers by the end of the teaching session.

- The client will demonstrate accurate measurement of their peak flow reading (PEFR) by the end of the teaching session.

- The client and/or family member will verbalize how to accurately use the Asthma Action Plan to manage worsening symptoms of asthma by the end of the teaching session.

- The client will verbalize how to use relaxation techniques to help manage feelings of anxiety when feeling short of breath by the end of the teaching session.

- The client will verbalize at least two personal triggers that contribute to worsening asthma symptoms by the end of the teaching session.

Interventions

Medical Interventions

Medical interventions for asthma aim to achieve effective symptom control, improve lung function, prevent exacerbations, and enhance the client’s quality of life. These interventions are prescribed by health care providers based on the individual’s asthma severity, current symptoms related to their baseline, their asthma action plan, and specific triggers.

Common medical interventions used to address chronic asthma include lifestyle modifications, medication management, immunizations, asthma action plans, and surgical treatment.

Lifestyle Modifications

Clients with asthma are advised to identify and minimize exposure to allergens or irritants that trigger their asthma, such as pollen, dust mites, or pet dander. They are also encouraged to receive flu, COVID, and pneumococcal vaccines to reduce the risk of respiratory infections that can trigger asthma exacerbations. For clients who smoke, quitting is strongly recommended to reduce exposure to irritants. For clients who don’t smoke, exposure to second-hand tobacco smoke should be avoided.

Medication Therapy

The goal of asthma therapy is to control asthma symptoms with the least amount of medication and minimal risk for adverse effects. A “stepwise approach to therapy” is used by health care providers in determining the type of medication(s) prescribed, their dosage(s), and frequency of administration. These medications are increased as necessary and decreased when possible. Because asthma is a chronic inflammatory disorder of the airways with recurrent exacerbations, medication therapy focuses on long-term suppression of inflammation to prevent exacerbations. See Figure 6.21[21] for an illustration of the stepwise approach to asthma therapy.[22]

As illustrated in Figure 6.21, several types of medication are prescribed to control asthma symptoms and prevent asthma attacks, as well as additional medications like anti-IgE monoclonal antibodies and immunomodulators[23],[24],[25],[26]:

- Inhaled Bronchodilators

- Short-Acting Beta-Agonists (SABA): SABAs relax airway smooth muscles and rapidly relieve bronchoconstriction. SABAs are used as “rescue” medications during asthma attacks to quickly relieve acute symptoms.

- Long-Acting Beta-Agonists (LABA): LABAs like salmeterol provide long-term bronchodilation.

- Inhaled Corticosteroids: Inhaled corticosteroids, such as fluticasone and budesonide are anti-inflammatory medications that reduce airway inflammation. They are used for long-term prevention and management of asthma symptoms.

- Combination Inhalers With Inhaled Corticosteroid and Long-Acting Beta-Agonists (ICS-LABA): ICS-LABA combination inhalers like fluticasone/salmeterol, commonly known by the brand name Advair, reduce airway inflammation and promote bronchodilation to prevent asthma symptoms.

- Oral or Intravenous Corticosteroids: A short course of an oral corticosteroid, such as prednisone, may be prescribed for clients in the “Yellow Zone” to reduce inflammation and swelling in the airways. Clients receiving emergency care for an acute asthma attack may receive intravenous administration of corticosteroids, such as methylprednisolone, for rapid reduction of airway swelling and inflammation.

- Leukotriene Modifiers: Oral leukotriene modifiers such as montelukast are used for long-term prevention of asthma symptoms and reduction of inflammation and bronchoconstriction by targeting leukotrienes that are involved in an allergic response related to asthma.

- Cromolyn: Cromolyn reduces the release of inflammatory mediators, including histamine and leukotrienes that cause bronchoconstriction and allergic symptoms that can trigger asthma.

- Methylxanthine: Methylxanthine, commonly known as theophylline, is an older medication used to treat asthma that may be prescribed if other alternatives are not effective. It decreases inflammation and causes bronchodilation but requires close monitoring of serum levels because it has a narrow range between therapeutic and toxic levels.

- Anti-IgE Monoclonal Antibodies: Monoclonal antibodies that target IgE, such as omalizumab, can be effective in reducing acute asthma exacerbations and improving quality of life for clients with severe asthma who have an allergic response component.[27]

- Immunomodulators: Mepolizumab is a biologic therapy that regulates levels of eosinophils, blood cells that often trigger asthma in individuals with an allergic component.

- Oxygen Therapy: Oxygen therapy is not a standard treatment for asthma management, but it may be used during acute asthma exacerbations for clients in the Red Zone.

To read additional information about common medication classes used to treat asthma, visit the “Respiratory” chapter in Open RN Nursing Pharmacology, 2e.

Asthma Action Plans

An individual diagnosed with asthma should have a written “Asthma Action Plan” from their health care provider that advises them how to self-manage their asthma at home. Asthma Action Plans have three zones, referred to as green, yellow, and red.

Green Zone

Individuals whose asthma symptoms are well-controlled are considered to be in the Green Zone. This means they don’t have a cough, wheeze, chest tightness, or shortness of breath during the day or night, and they can do their usual activities. If they use a peak flow meter to monitor and manage their asthma, their peak flow reading is at least 80% of their personal best.[28] Peak flow meters are further discussed under the “Diagnostic Testing” subsection.

Individuals in the green zone should continue taking their asthma medications as prescribed. If exercise is an asthma trigger for an individual, their Asthma Action Plan may advise quick-relief medication before exercising to prevent an asthma attack (sometimes referred to as “pre-treatment”).

Yellow Zone

Individuals are considered to be in the Yellow/Caution Zone when their asthma symptoms are worsening, including one or more of the following[29]:

- Coughing, wheezing, chest tightness, or shortness of breath

- Waking at night due to asthma

- Able to do some, but not all of their usual activities

If a client uses a peak flow meter to monitor and manage their asthma, peak flow readings of 50 to 79% of their personal best indicate they are in the Yellow Zone. Individuals in the Yellow Zone should take their prescribed asthma medications as listed in the Green Zone of their Asthma Action Plan, plus additional medications as described in the Yellow Zone, such as a quick-relief inhaler and possibly an oral corticosteroid. They should also call their doctor as instructed.[30] Individuals who experience Yellow Zone symptoms two or more times per week should contact their health care provider for a follow-up appointment because this frequency means their asthma is not considered “well-controlled,” and they are at risk for a severe asthma attack.[31]

Red Zone

Individuals are considered to be in the Red/Medical Alert Zone if they are experiencing asthma symptoms that are worsening without resolution. Severe asthma episodes can be life-threatening and require emergency care. Signs and symptoms of an asthma emergency that requires urgent medical care include one or more of the following criteria[32]:

- Feeling very short of breath

- Symptoms are not relieved by quick-relief medicines

- Unable to do usual activities

- Same or worsening symptoms after 24 hours in Yellow Zone

Infants, toddlers, and children may have different asthma emergency signs and symptoms than adults. Additional signs and symptoms of a severe asthma episode in infants, toddlers, and children include the following[33]:

- Nasal flaring (i.e., nostrils are opening widely)

- Exaggerated belly breathing

- Failing to recognize or respond to their parents

- Irritable, agitated, and/or sluggish

- Nasal grunting on expiration

Individuals in the Red Zone should immediately take a quick-relief medication and an oral corticosteroid and then call their health care provider. If they are still in the Red Zone after 15 minutes AND they have not reached their provider, they should go to the emergency room or call an ambulance. If at any time they experience trouble walking and talking due to shortness of breath or their lips or fingernails become cyanotic, they should take another dose of quick-relief medication and immediately call 911 or go to the emergency room.[34]

View or download the most recent copy of an Asthma Action Plan document from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute.[35]

Surgical Interventions

Clients with severe asthma for whom conventional treatment is not effective may undergo bronchial thermoplasty. This procedure is performed during a bronchoscopy and delivers heat to the muscles surrounding the airways to reduce smooth muscle mass and prevent them from narrowing.[36],[37],[38]

Nursing Interventions

Nursing interventions for asthma are aimed at symptom management and facilitating overall respiratory health through medication management, health teaching, and psychosocial support.

Medication Management

Nurses safely administer prescribed medications, evaluate their effectiveness, and monitor for potential side effects. They provide teaching about the purpose and use of medications as further described under the “Health Teaching” section.

Dyspnea Management

Nurses implement and teach strategies for managing dyspnea during asthma attacks, in addition to administering medication. For example, sitting upright or using tripod positioning can help with lung expansion, and pursed-lip breathing reduces air trapping that can occur during an asthma attack. Review enhanced breathing techniques in the “General Nursing Interventions Related to Respiratory Alterations” subsection earlier in this chapter.

Health Teaching

Nurses provide comprehensive asthma education to clients and their family members, caregivers, or significant others. Teaching focuses on symptoms of asthma, triggers of their asthma attacks, how to use their prescribed medications according to their Asthma Action Plan, and when to contact their provider with worsening symptoms. See teaching topics related to the Asthma Action Plan in the following box.

A Closer Look: Health Teaching Regarding Asthma Action Plans[39]Clients with asthma should have a written action plan developed in collaboration with their health provider. If the client does not have a written action plan, the nurse should advocate for one. Nurses provide education to the client and their family members regarding how to use the Asthma Action Plan and check for understanding.

Green Zone (Good Control): Teaching topics include the following:

- Using long-term control medications as prescribed.

- Identifying and avoiding triggers.

- Monitoring peak flow readings.

- Premedicating before exercise, if exercise is a trigger.

Yellow Zone (Caution): Teaching topics include the following:

- Understanding the symptoms that indicate the Yellow Zone.

- Using quick-relief medications and oral corticosteroids.

- Monitoring peak flow readings.

- Notifying the health care provider.

Red Zone (Danger): Teaching topics include the following:

- Knowing the symptoms that indicate the Red Zone.

- Understanding the actions to take if in the Red Zone.

- Knowing when to call the health care provider and/or seek emergency medical care.

It is helpful for the client to have written materials during and after the teaching session. See information on free handouts in the following box.

The National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute provides free resources that can be downloaded and printed for clients.39 Here are a few key handouts that can be used during health teaching sessions:

- Monitoring Your Asthma with instructions on how to use a peak flow meter

- How to Use a Metered-Dose Inhaler

- How to Use a Nebulizer

- How to Use a Dry Powder Inhaler

Psychosocial Support

Nurses offer psychosocial support to clients with chronic disease to help them cope with the challenges of managing their symptoms and achieving quality of life.

It is common for clients with asthma and their family members to experience anxiety when dyspnea occurs. Anxiety can worsen dyspnea because it stimulates rapid, shallow breathing. During an asthma attack, in addition to implementing interventions to promote oxygenation, the nurse maintains a calm environment, stays with the client, and encourages relaxation techniques to decrease anxiety. Nurses can demonstrate and encourage the use of focused breathing, guided imagery, and progressive relaxation. Music therapy, based on the client’s preferences, may also be helpful to promote relaxation. After an asthma attack has resolved, nurses teach clients and their family members how to use relaxation techniques to help manage anxiety while also using their Asthma Action Plan to manage their respiratory symptoms.[40]

Nurses also assess the coping skills, available resources, and social support for clients with asthma. By reinforcing the Asthma Action Plan, nurses focus on positive coping strategies and self-monitoring techniques that reaffirm the client’s and the family’s ability to deal with the chronic illness. Effective resources and support can reduce asthma symptoms and result in fewer unscheduled health care visits, fewer activity limitations, and improved school/work attendance.[41],[42]

Evaluation

During the evaluation stage, nurses determine the effectiveness of nursing interventions for a specific client. The previously identified expected outcomes are reviewed to determine if they were met, partially met, or not met by the time frames indicated. If outcomes are not met or only partially met by the time frame indicated, the nursing care plan is revised. Evaluation should occur every time the nurse implements interventions with a client, reviews updated laboratory or diagnostic test results, or discusses the care plan with other members of the interprofessional team.

Asthma Case Study

Jeremy, a 13-year-old boy, was brought to the emergency room by his parents after experiencing acute respiratory distress while playing basketball with his friends. He complained of chest tightness, severe shortness of breath, and audible wheezing. Members of Jeremy’s family have experienced a “cold” within the last two weeks.

The following details are relevant to Jeremy’s case:

- Peak Flow Meter Reading: 180 (Personal Best: 425)

- Pulse Oximetry (SpO2): 90%

Jeremy attempted to manage his acute symptoms at home by using his salmeterol inhaler. However, he reported that it did not provide any relief.

1. What is your hypothesis for Jeremy’s current condition and what are two possible causes?

Hypothesis: Acute asthma exacerbation

Possible Causes:

- Respiratory Infection: The recent “cold” affecting his family members suggests that Jeremy may have contracted a viral respiratory infection, a common trigger for asthma exacerbations.

- Physical Exertion: Playing basketball can be physically demanding and may have triggered his asthma symptoms, especially if he did not use a pre-exercise bronchodilator inhaler, if prescribed.

2. How would you teach Jeremy and his parents about his salmeterol inhaler and why did it not offer relief?

- Explain that Serevent is a long-acting beta-agonist (LABA) bronchodilator, which is primarily used for maintenance therapy, not for immediate relief during an asthma attack.

- Emphasize the importance of using a short-acting beta-agonist (e.g., albuterol) for quick relief during acute symptoms.

- Teach Jeremy and his parents to differentiate between their maintenance and rescue inhalers and when to use each.

3. Evaluate Jeremy’s peak flow reading. What zone is he in? What will you teach Jeremy and his parents regarding his asthma management using peak flow meter readings and the Asthma Action Plan?

Jeremy’s peak flow reading is 180, significantly below his personal best of 425.

Jeremy is in the “Red Zone,” indicating a severe asthma exacerbation.

Teaching will include the following: Regularly monitor peak flow measurements because peak flow readings help monitor lung function and assess asthma control. Reinforce the three zones (Green, Yellow, Red) in his Asthma Action Plan and actions to take:

- Green Zone (Good Control): No symptoms and peak flow reading 80% or higher compared to his personal best.

- Yellow Zone (Caution): Worsening symptoms. Peak flow reading between 50% and 79%. Follow the Asthma Action Plan in self-administering prescribed medications and contacting the health care provider.

- Red Zone (Medical Alert): Immediate action is required. Administer quick-relief medication and contact the health care provider. Obtain emergency medical care as described.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2023, May 22). Asthma. https://www.cdc.gov/asthma/default.htm ↵

- National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. (2022, March 24). What is asthma? National Institutes of Health. https://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health/asthma ↵

- Litonjua, A. A., & Weiss, S. T. (2023). Risk factors for asthma. UpToDate. Retrieved September 23, 2023, from https://www.uptodate.com/ ↵

- “Asthma_attack-illustration_NIH.jpg” by United States-National Institute of Health: National Heart, Lung, Blood Institute is licensed in the Public Domain. ↵

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2023, May 22). Asthma. https://www.cdc.gov/asthma/default.htm ↵

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2023, May 22). Asthma. https://www.cdc.gov/asthma/default.htm ↵

- “Asthma_triggers_2.PNG” by 7mike5000 is licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0 ↵

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2023, May 22). Asthma. https://www.cdc.gov/asthma/default.htm ↵

- Litonjua, A. A., & Weiss, S. T. (2023). Risk factors for asthma. UpToDate. Retrieved September 23, 2023, from https://www.uptodate.com/ ↵

- Fanta, C., & Barrett, N. (2023). An overview of asthma management. UpToDate. Retrieved September 30, 2023, from https://www.uptodate.com/ ↵

- Wenzel, S. (2023). Treatment of severe asthma in adolescents and adults. UpToDate. Retrieved September 30, 2023, from https://www.uptodate.com/ ↵

- Asthma and Allergy Foundation of America. (2022, January). Asthma symptoms. https://aafa.org/asthma/asthma-symptoms/ ↵

- Asthma and Allergy Foundation of America. (2022, January). Asthma symptoms. https://aafa.org/asthma/asthma-symptoms/ ↵

- Asthma and Allergy Foundation of America. (2022, January). Asthma symptoms. https://aafa.org/asthma/asthma-symptoms/ ↵

- Asthma and Allergy Foundation of America. (2022, January). Asthma symptoms. https://aafa.org/asthma/asthma-symptoms/ ↵

- Litonjua, A. A., & Weiss, S. T. (2023). Risk factors for asthma. UpToDate. Retrieved September 23, 2023, from https://www.uptodate.com/ ↵

- Fanta, C., & Barrett, N. (2023). An overview of asthma management. UpToDate. Retrieved September 30, 2023, from https://www.uptodate.com/ ↵

- Wenzel, S. (2023). Treatment of severe asthma in adolescents and adults. UpToDate. Retrieved September 30, 2023, from https://www.uptodate.com/ ↵

- “Peak_flow_meter_Philips_Respironics_PersonalBest_2019-11-29_5272.jpg” by Salicyna is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0 ↵

- Flynn Makic, M. B., & Martinez-Kratz, M. R. (2023). Ackley and Ladwig’s Nursing diagnosis handbook: An evidence-based guide to planning care (13th ed.). Elsevier. ↵

- "Stepwise_approach_for_managing_asthma_in_youths_greater_than_or_equal_to_12_years_of_age_and_adults.gif" by National Heart, Blood, and Lung Institute is licensed under CC BY 2.5 ↵

- National Asthma Education and Prevention Program, Third Expert Panel on the Diagnosis and Management of Asthma. Expert Panel Report 3: Guidelines for the Diagnosis and Management of Asthma. (2007). Stepwise approach for managing asthma in youths ≥12 years of age and adults. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK7222/ ↵

- This work is a derivative of StatPearls by Sharma, Hashmi, & Chakraborty and is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- Litonjua, A. A., & Weiss, S. T. (2023). Risk factors for asthma. UpToDate. Retrieved September 23, 2023, from https://www.uptodate.com/ ↵

- Fanta, C., & Barrett, N. (2023). An overview of asthma management. UpToDate. Retrieved September 30, 2023, from https://www.uptodate.com/ ↵

- Wenzel, S. (2023). Treatment of severe asthma in adolescents and adults. UpToDate. Retrieved September 30, 2023, from https://www.uptodate.com/ ↵

- Kardas, G., Panek, M., Kuna, P., Damiański, P., & Kupczyk, M. (2022). Monoclonal antibodies in the management of asthma: Dead ends, current status and future perspectives. Frontiers in Immunology, 13, 983852. https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2022.983852 ↵

- National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. (2022, March 24). What is asthma? National Institutes of Health. https://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health/asthma ↵

- National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. (2022, March 24). What is asthma? National Institutes of Health. https://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health/asthma ↵

- National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. (2022, March 24). What is asthma? National Institutes of Health. https://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health/asthma ↵

- Asthma and Allergy Foundation of America. (2022, January). Asthma symptoms. https://aafa.org/asthma/asthma-symptoms/ ↵

- National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. (2022, March 24). What is asthma? National Institutes of Health. https://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health/asthma ↵

- National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. (2022, March 24). What is asthma? National Institutes of Health. https://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health/asthma ↵

- National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. (2022, March 24). What is asthma? National Institutes of Health. https://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health/asthma ↵

- National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. (2022, March 24). What is asthma? National Institutes of Health. https://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health/asthma ↵

- Litonjua, A. A., & Weiss, S. T. (2023). Risk factors for asthma. UpToDate. Retrieved September 23, 2023, from https://www.uptodate.com/ ↵

- Fanta, C., & Barrett, N. (2023). An overview of asthma management. UpToDate. Retrieved September 30, 2023, from https://www.uptodate.com/ ↵

- Wenzel, S. (2023). Treatment of severe asthma in adolescents and adults. UpToDate. Retrieved September 30, 2023, from https://www.uptodate.com/ ↵

- Fanta, C., & Barrett, N. (2023). An overview of asthma management. UpToDate. Retrieved September 30, 2023, from https://www.uptodate.com/ ↵

- Martin, P. (2023, October 13). 6 asthma nursing care plans. NursesLabs. https://nurseslabs.com/asthma-nursing-care-plans/ ↵

- Martin, P. (2023, October 13). 6 asthma nursing care plans. NursesLabs. https://nurseslabs.com/asthma-nursing-care-plans/ ↵

- Cicutto, L., Gleason, M., Haas-Howard, C., et al. (2018). Building bridges for asthma care program: A school-centered program connecting schools, families, and community health-care providers. The Journal of School Nursing, 36(3), 168-180. https://doi.org/10.1177/1059840518805824 ↵

A condition caused by chronic inflammation in the airways, resulting in narrowed air passages. Individuals also experience bronchoconstriction that tightens the smooth muscle surrounding the airways, further limiting airflow.

A severe and life-threatening asthma attack that is unresponsive to standard treatments such as bronchodilators and corticosteroids.

Involves a handheld device called a peak flow meter that measures the rate of air that can be forcefully breathed out of the lungs.

Measures the rate of air that can be forcefully breathed out of the lungs.

Procedure is performed during a bronchoscopy and delivers heat to the muscles surrounding the airways to reduce smooth muscle mass and prevent them from narrowing.