6.9 Tuberculosis

Overview

Tuberculosis (TB) is a contagious bacterial infection caused by Mycobacterium tuberculosis. It primarily affects the lungs but can also target other parts of the body. TB spreads through the air when an infected person coughs or sneezes, releasing small infectious droplets into the environment. It is a serious public health concern worldwide.[1]

Pharmacology

TB is caused by an organism called a bacillus that enters the lung. Over the course of 2 to 12 weeks, the bacillus replicates and the immune response becomes activated. The immune response involves macrophages and lymphocytes migrating to the site of inflammation and walling off the bacillus, forming a tubercle. Over time, cheese-like material develops in the center of the tubercle, called caseous necrosis. Individuals with healthy immune systems may heal this initial lesion and develop latent TB before any signs or symptoms of the illness occur. However, the tubercle may calcify and remain dormant for many years, but over time, or in immunocompromised states, spread to other areas of the lung or to other organs.

There are several risk factors for TB. Primary risk factors include close contact with an TB-infected person, HIV infection or otherwise weakened immune system, and substance abuse. TB is a common disease around the world, so individuals who travel or live in regions with high TB prevalence such as Africa, Asia, or parts of Latin America have increased risk. Individuals who immigrate from high-incidence countries or experience homelessness are also at increased risk. Additionally, individuals who live in overcrowded conditions are at increased risk for TB transmission, including individuals who work or live in long-term health care settings or prisons.[2]

In regions of the world with high TB prevalence, a Bacillus Calmette-Guérin (BCG) vaccine is commonly administered. Receiving a BCG vaccine has a substantial effect on tuberculin skin test reactivity, with individuals who received BCG after infancy having tuberculin skin test reactions up to 55 years post-immunization.[3] Nurses must be aware of an individual’s history of receiving a BCG vaccine when interpreting the results of a tuberculin skin test. Anyone who has received the BCG vaccine within the last ten years will have a positive test result for their skin test.

Mycobacterium tuberculosis has developed drug resistance in many areas of the world, causing a significant treatment problem. Multidrug-resistant TB (MDR TB) is caused by an organism that is resistant to at least isoniazid and rifampin, the two most potent TB drugs used to treat all persons with TB disease. Extensively drug resistant TB (XDR TB) is a rare type of MDR TB that is resistant to isoniazid and rifampin, plus any fluoroquinolone and at least one of the second-line drugs. XDR TB is of special concern for persons with HIV infection or other conditions that weaken the immune system. These persons are more likely to develop TB disease once they are infected, and they also have a higher risk of death once they develop TB. Resistance to anti-TB medications can occur when these drugs are mismanaged. Examples of mismanagement include when individuals do not complete their full course of treatment; when health care providers prescribe the wrong treatment, the wrong dose, or length of time for taking the drugs; when the supply of drugs is not always available; or when the drugs are of poor quality. The most important thing a person can do to prevent the spread of MDR TB is to take all of their medications exactly as prescribed by their health care provider. No doses should be missed, and treatment should not be stopped early.[4]

Assessment

Tuberculosis (TB) can affect various body systems, but it primarily targets the respiratory system. TB can mimic other diseases, and its presentation can vary widely among individuals. Identifying TB through clinical manifestations and diagnostic tests is crucial for early diagnosis and treatment. TB is a contagious disease, and timely intervention helps prevent its spread to others. It is important to note that some forms of tuberculosis may present with minimal or no symptoms, known as latent tuberculosis infection (LTBI). In LTBI, the individual carries the TB bacteria but does not exhibit active disease. See Table 6.9 for a summary of potential clinical manifestations of tuberculosis across body systems.

Table 6.9. Clinical Manifestations of Tuberculosis Across Body Systems[5],[6]

| Body System | Clinical Manifestations |

|---|---|

| Respiratory | Persistent cough for more than two weeks, hemoptysis, purulent sputum, pleuritic chest pain, dyspnea, and adventitious lung sounds. |

| General | Fever, chills, night sweats, fatigue, malaise (general discomfort), weakness, unexplained weight loss, and loss of appetite. |

| Lymphatic | Lymphadenopathy (swelling of lymph nodes), especially in the neck. |

| Nervous | Tuberculous meningitis can lead to symptoms such as severe headache, confusion, stiffness of the neck, and neurological deficits. |

| Genitourinary | Renal tuberculosis can cause hematuria (blood in the urine) and flank pain. |

| Musculoskeletal | Tuberculous osteomyelitis may lead to bone pain, joint pain, and limited mobility of affected joints. |

| Skin and Soft Tissues | Cutaneous tuberculosis can result in skin lesions or ulcers. |

Diagnostic Testing

Diagnosing tuberculosis (TB) involves a combination of clinical assessment, imaging, and laboratory tests to confirm the presence of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. If diagnostic tests reveal a positive result, TB is a reportable disease to the public health department.

A combination of tests may be necessary to confirm a TB diagnosis, and prompt diagnosis and treatment are crucial to prevent the spread of TB and improve client outcomes. Diagnostic testing may include the following[7],[8]:

- Tuberculin Skin Test (Mantoux Test): A small amount of tuberculin protein is injected just beneath the skin, usually in the forearm. The test is read 48 to 72 hours later to check for induration at the injection site. A positive reaction indicates exposure to TB or the BCG vaccine, but it does not confirm active disease. Further testing is needed to determine if the infection is active or latent.

- Blood Tests (Interferon-Gamma Release Assays – IGRA): These tests measure the body’s immune response to TB by detecting the release of interferon-gamma when exposed to TB proteins. Common IGRA tests include the QuantiFERON-TB Gold In-Tube (QFT-GIT) and the T-SPOT TB tests. Blood tests are particularly useful when the tuberculin skin test results may be affected by prior BCG vaccination or other factors.

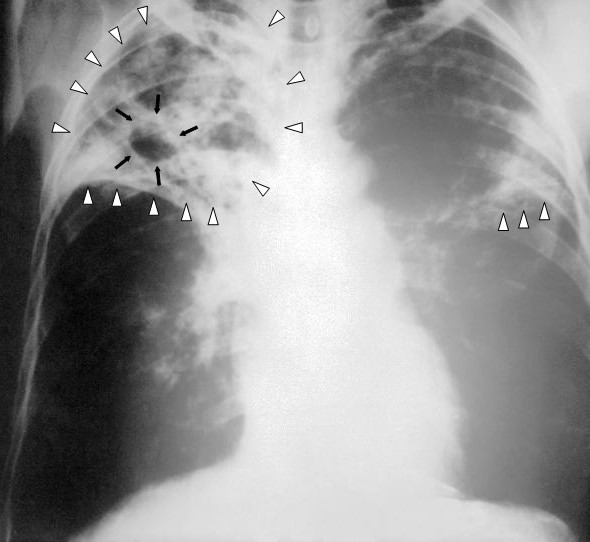

- Chest X-ray: A chest X-ray is used to detect pulmonary TB and assess the extent of lung involvement. However, active TB cannot be distinguished from inactive disease using only radiography. See Figure 6.26[9] for an image of a chest X-ray illustrating advanced active TB.

- Sputum Smear Microscopy: A sputum sample is examined in a lab under a microscope to detect acid-fast bacilli (AFB). It is a rapid method for diagnosing pulmonary TB. However, it may not always detect the Mycobacterium tuberculosis bacteria, particularly in early stages.

- Sputum Culture: A sputum sample is cultured to grow the Mycobacterium tuberculosis bacteria. A sputum culture confirms the diagnosis of active TB and is also used to evaluate the effectiveness of treatment. Culture allows for drug susceptibility testing to determine which antibiotics are effective against the specific strain. It is more sensitive than smear microscopy but takes several weeks to yield results.

- Nucleic Acid Amplification Tests (NAAT): NAAT tests can rapidly detect TB and simultaneously assess resistance to rifampin, an important anti-TB drug. These tests are particularly valuable in diagnosing drug-resistant TB. This type of test is performed by obtaining a swab of respiratory material.

- Bronchoscopy and Bronchoalveolar Lavage (BAL): These procedures involve inserting a thin, flexible tube into the airways and collecting samples for testing. They are used when sputum samples are not obtainable or when there is a need for a definitive diagnosis.

- Biopsy: A biopsy may be necessary if there is suspicion of extrapulmonary TB, affecting organs outside the lungs. Biopsies are performed to examine tissue samples for the presence of TB.

- Molecular Diagnostic Tests: These tests are highly sensitive and provide rapid results. They can identify Mycobacterium tuberculosis and determine rifampin resistance.

Nursing Problems and Diagnoses

Nursing care for clients with TB focuses on promoting adherence to treatment, preventing the spread of the disease, and addressing the physical and psychosocial challenges associated with TB.

Common NANDA nursing diagnoses for clients with TB include the following[10]:

- Ineffective Airway Clearance R/T excessive secretions

- Fatigue R/T disease state

- Impaired Gas Exchange R/T disease process

- Readiness for Enhanced Health Self-Management R/T taking medications according to prescribed protocol for prevention and treatment

- Social Isolation R/T treatment protocol

Outcome Identification

Outcome identification includes setting short- and long-term goals and creating expected outcome statements customized for the client’s specific needs. Expected outcomes are statements of measurable action for the client within a specific time frame that are responsive to nursing interventions.

Sample expected outcomes for common nursing diagnoses related to tuberculosis are as follows:

- The client will effectively clear airway secretions as evidenced by improved breath sounds and productive coughing.

- The client will maintain adequate oxygenation with oxygen saturation levels above 92%.

- The client will verbalize the importance of adhering to prescribed therapy for the full treatment plan.

- The client will verbalize three positive coping strategies before discharge from the hospital.

Interventions

Medical Interventions

Medical interventions for tuberculosis (TB) are primarily aimed at treating the infection and preventing its spread. Treatment regimens for TB typically involve a combination of antibiotics taken for an extended period of time and the implementation of airborne transmission precautions when the disease is active.[11],[12]

Medication Therapy

The cornerstone of TB treatment involves a combination of antibiotics to effectively kill the Mycobacterium tuberculosis bacteria. The standard treatment includes four first-line drugs: isoniazid, rifampin, ethambutol, and pyrazinamide. Drug-sensitive TB is treated with a combination of these antibiotics over a period of four to nine months, with the initial phase lasting two months. Multi-drug-resistant TB (MDR-TB) and extensively drug-resistant TB (XDR-TB) require more complex regimens with second-line drugs. Treatment for drug-resistant TB may last 18 to 24 months or longer. The selection of drugs and treatment duration depend on the type of TB and individual client factors. After medication therapy has been initiated, sputum cultures are obtained at specific intervals to monitor the presence of acid-fast bacilli (AFB) and to assess treatment response. Clients are considered infectious until three negative sputum samples have been obtained, typically after approximately three months of treatment.

To ensure medication adherence and reduce the risk of developing drug resistance, health care workers or trained observers may directly observe clients taking their medications, referred to as directly observed therapy (DOT). DOT is a crucial intervention to assist with medication compliance, prevent treatment failure, and control the spread of drug-resistant TB.

Infection Control

Clients who are diagnosed with active TB and are hospitalized have airborne transmission precautions in place, including placement in private rooms with special air venting. Health care workers wear N95 masks when caring for clients with active TB. Individuals in close contact with newly diagnosed clients are tested and monitored for TB infection. Prophylactic treatment may be offered to those exposed to TB to prevent the progression to active TB.

Nursing Interventions

Nursing interventions for tuberculosis (TB) supporting adherence to treatment and preventing the spread of the disease.

Medication Management

For clients receiving inpatient care, nurses administer prescribed medications. During outpatient care, nurses may assist in providing directly observed therapy (DOT) to ensure clients take their medications as directed for the full course of treatment to help prevent the development of drug resistance. Nurses also monitor and teach clients about potential side effects of their medications, including when to notify their health care provider.

Health Teaching

Nurses teach clients cough etiquette, respiratory hygiene, and proper disposal of tissues to prevent the spread of infection. Airborne transmission precautions, including the use of N95 masks, are explained to hospitalized clients and their family members.

Malnutrition is common in clients with TB. Nurses monitor for signs of malnutrition and advocate for referrals to dieticians for meal plans and supplements to support weight gain and overall health.

Psychosocial Support

Nurses assess the psychosocial impact of TB, considering the potential stigma and anxiety associated with the disease. They provide emotional support to clients and their family members to help them cope with the diagnosis. They also advocate for client access to health care services and help them navigate the health care system and connect with appropriate resources.

Evaluation

During the evaluation stage, nurses determine the effectiveness of nursing interventions for a specific client. The previously identified expected outcomes are reviewed to determine if they were met, partially met, or not met by the time frames indicated. If outcomes are not met or only partially met by the time frame indicated, the nursing care plan is revised. Evaluation should occur every time the nurse implements interventions with a client, reviews updated laboratory or diagnostic test results, or discusses the care plan with other members of the interprofessional team.

- Menzies, D. (2023). Tuberculosis infection (latent tuberculosis) in adults: Approach to diagnosis (screening). UpToDate. Retrieved October 5, 2023, from https://www.uptodate.com/ ↵

- Menzies, D. (2023). Tuberculosis infection (latent tuberculosis) in adults: Approach to diagnosis (screening). UpToDate. Retrieved October 5, 2023, from https://www.uptodate.com/ ↵

- This work is a derivative of StatPearls by Okafor, Rewane, & Momodu and is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2023, August 29). Tuberculosis (TB). https://www.cdc.gov/tb/default.htm ↵

- Menzies, D. (2023). Tuberculosis infection (latent tuberculosis) in adults: Approach to diagnosis (screening). UpToDate. Retrieved October 5, 2023, from https://www.uptodate.com/ ↵

- Bernardo, J. (2022). Diagnosis of pulmonary tuberculosis in adults. UpToDate. Retrieved October 5, 2023, from https://www.uptodate.com/ ↵

- Menzies, D. (2023). Tuberculosis infection (latent tuberculosis) in adults: Approach to diagnosis (screening). UpToDate. Retrieved October 5, 2023, from https://www.uptodate.com/ ↵

- Bernardo, J. (2022). Diagnosis of pulmonary tuberculosis in adults. UpToDate. Retrieved October 5, 2023, from https://www.uptodate.com/ ↵

- “Tuberculosis-x-ray-1.jpg” by Unknown author, for the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, is licensed in the Public Domain. ↵

- Flynn Makic, M. B., & Martinez-Kratz, M. R. (2023). Ackley and Ladwig’s Nursing diagnosis handbook: An evidence-based guide to planning care (13th ed.). Elsevier. ↵

- Menzies, D. (2023). Tuberculosis infection (latent tuberculosis) in adults: Approach to diagnosis (screening). UpToDate. Retrieved October 5, 2023, from https://www.uptodate.com/ ↵

- Bernardo, J. (2022). Diagnosis of pulmonary tuberculosis in adults. UpToDate. Retrieved October 5, 2023, from https://www.uptodate.com/ ↵

A contagious bacterial infection caused by Mycobacterium tuberculosis.