9.5 Alzheimer’s Disease

Dementia is a general term that refers to a decline in cognitive ability severe enough to interfere with a person’s ability to complete their activities of daily living. Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is the most common type of dementia, accounting for at least two thirds of cases of dementia in people aged 65 and older. AD is a neurodegenerative disease that causes progressive and disabling impairment of cognitive functions, including memory, comprehension, language, attention, reasoning, and judgment. An estimated 6.7 million Americans are living with AD.[1]

Family members commonly function as unpaid caregivers to support individuals with AD who continue to live at home, including assistance with activities of daily living (ADLs), paying bills, shopping, and preparing meals. Caregivers also provide emotional support, help manage health conditions, and ensure safety at home. Caregiving is time-intensive and can be physically and emotionally exhausting, causing declines in the caregiver’s health.[2] Nurses often address caregiver health when caring for clients with AD.

Pathophysiology

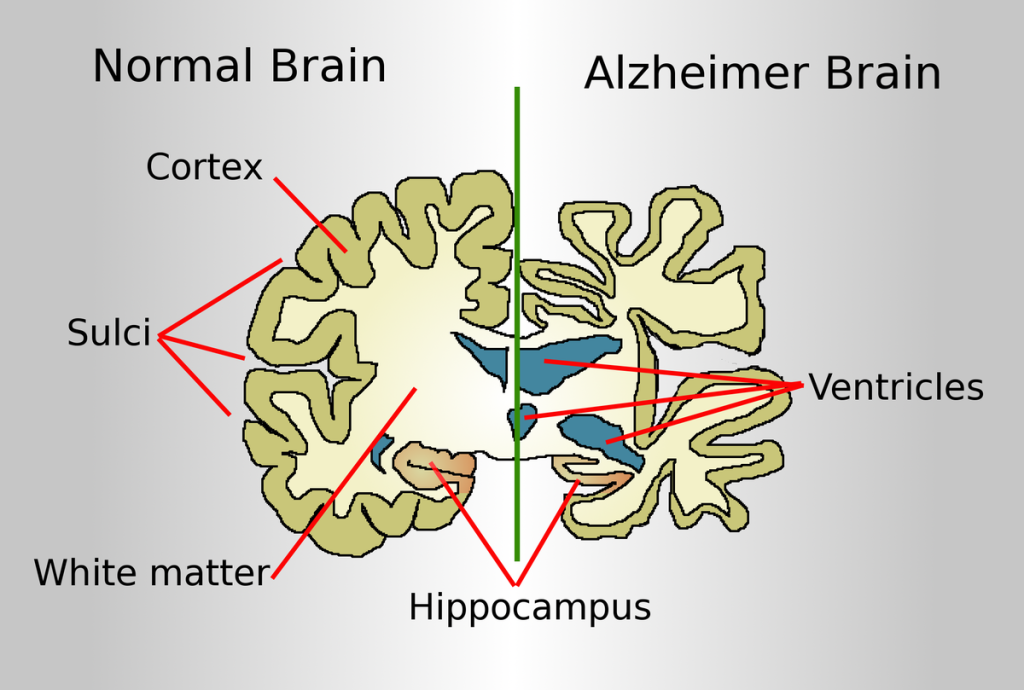

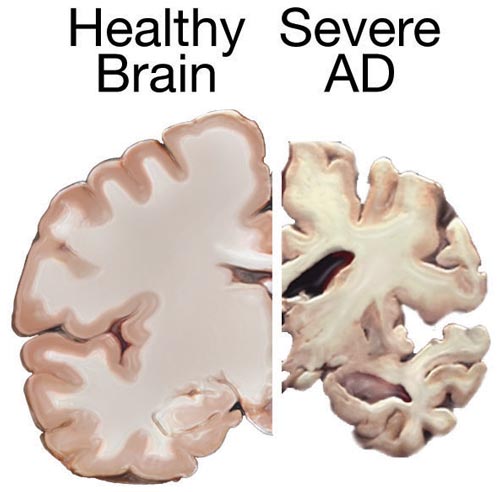

The brain of an older adult experiences normal physiological changes associated with aging, such as increased size of the ventricles. However, with Alzheimer’s disease and other forms of dementia, these changes occur at a much more rapid pace, along with significant atrophy of the cerebral cortex and degeneration of neurons. See Figures 9.12[3] and 9.13[4] for illustrations comparing a normal brain to a brain of a person with Alzheimer’s disease.

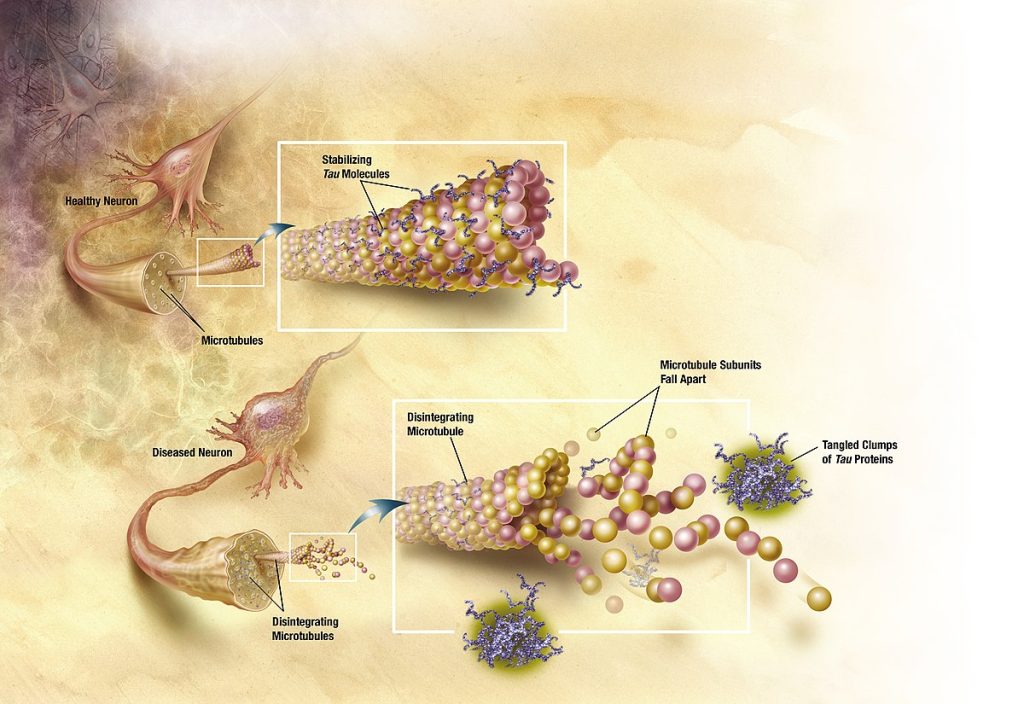

The hallmark microscopic changes of AD consist of neurofibrillary tangles and neuritic plaques. Neurofibrillary tangles consist of fibrous tissue that impair the transmission of impulses from neuron to neuron. Neuronal transmission is further hindered by neuritic plaques, composed of abnormal proteins called beta amyloid and tau, that damage the neurons. See Figure 9.14[5] for an illustration of neurodegeneration caused by these abnormal proteins.

Initial neuron damage occurs in the parts of the brain responsible for memory, language, and thinking, so initial symptoms of Alzheimer’s disease are short-term memory loss and language and thinking problems. Brain changes that cause these symptoms are thought to begin 20 years or more before symptoms start.[6]

Imbalanced neurotransmitter levels are also associated with Alzheimer’s disease. For example, decreased levels of acetylcholine (ACh), norepinephrine, dopamine, and serotonin can further contribute to impaired cognition, loss of short-term/recent memory, and ability to retain new memories.

Risk Factors

The cause of Alzheimer’s disease is not certain. However, age, gender, and genetics are three major risk factors linked to AD, with increasing age being the greatest risk factor. The percentage of people with AD increases dramatically with age, with 33% of people aged 85 or older having AD. Females over 65 years old are more likely to develop AD than men, and having a first-degree relative with AD also increases one’s risk. There is also an increased incidence of AD in people who have Down’s syndrome. Certain medications are associated with higher risk for AD, including benzodiazepines, anticholinergics, and long-term use of proton pump inhibitors.[7],[8] Other risk factors may also play a role, such as exposures to toxic chemicals and immunological changes.[9],[10]

Although age, gender, and genetics cannot be changed, some risk factors can be modified to reduce the risk of cognitive decline and dementia. Examples of modifiable risk factors are participating in physical activity, stopping smoking, staying socially and mentally active, maintaining blood pressure in a normal range, and following a healthy diet.[11]

Some research also indicates that additional years of formal education builds cognitive reserve. Cognitive reserve refers to the brain’s ability to make flexible and efficient use of networks of neuron-to-neuron connections that enable a person to continue to carry out cognitive tasks despite degenerative brain changes. In addition to years of formal education, having a mentally stimulating job and engaging in other mentally stimulating activities may also help build cognitive reserve.[12]

Research on the impact of ethnicity finds a lower incidence of dementia in African Americans, but those diagnosed with dementia showed greater cognitive deficits, neuropsychiatric symptoms, severity of symptoms, and functional dependence.[13]

Evidence indicates that even mild traumatic brain injury (TBI) increases the risk of developing certain forms of dementia. A recent meta-analysis estimates that any form of TBI increases the risk for dementia by nearly 70%. Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) also increases the risk of dementia and is two to five times more common in veterans compared with the general population.[14]

A recent nationwide research study called New IDEAS (Imaging Dementia—Evidence for Amyloid Scanning) is looking for better ways to diagnose and care for people from diverse backgrounds who are experiencing changes in their memory, including mild cognitive impairment and dementia.[15] The goal of the New IDEAS study is to ensure that its results represent all racial and ethnic groups. As new treatments are being developed, the research hopes to provide information for safe and effective care for everyone, regardless of race, ethnicity, age, or gender.[16]

Read additional information in the 2023 Alzheimer’s Disease Facts and Figures PDF by the Alzheimer’s Association.

Read about the Alzheimer’s Association’s new IDEAS study.

Stages of Alzheimer’s Disease

The initial presenting symptom of AD is impaired short-term memory although long-term memory remains intact. Impaired short-term memory is followed by impaired problem-solving, judgment, executive functioning, motivation, and organization, leading to problems with multitasking and abstract thinking.

Alzheimer’s disease is classified into these different states based on the degree of cognitive impairment: mild, moderate, and severe[17]:

- Mild: Most people with mild AD are able to function independently but require assistance with some activities to maximize their independence and remain safe. Handling finances and paying bills may be especially challenging, and they may need more time to complete common daily tasks. They may still be able to drive, work, and participate in their favorite activities.

- Moderate: Individuals with moderate AD experience additional problems with memory and language, are more likely to become confused, and find it harder to complete multistep tasks such as bathing and dressing. They may wander, become incontinent, and have difficulty sleeping. Personality and behavioral changes may occur, including suspiciousness, agitation, and depression. They may experience increased confusion at night or when lighting is inadequate, referred to as sundowning. They may also begin to have difficulty recognizing loved ones.

- Severe: The ability to verbally communicate becomes greatly diminished in people with severe AD, and individuals are likely to require around-the-clock care. Because areas of the brain involved in movement become damaged, individuals become bed bound. Being bed-bound makes them vulnerable to additional medical complications resulting from immobility, including blood clots, pressure injuries, skin infections, and sepsis. Damage to areas of the brain that control swallowing causes dysphagia and can result in aspiration pneumonia, a contributing cause of death among many individuals with AD.

The symptoms of Alzheimer’s disease worsen over time. On average a person with Alzheimer’s disease lives four to eight years after diagnosis, but depending on variable factors, they may live as long as 20 years.

Assessment

Obtaining a thorough health history and physical assessment is important to distinguish AD from other forms of dementia and acute confusion, referred to as delirium. Interviewing family members or significant others may be necessary because clients with dementia may be unaware of their symptoms. Assessment should include the onset, duration, progression, and course of symptoms, as well as a complete functional status assessment.

Neuropsychological Tests

Neurologists or psychologists may administer several types of neuropsychological tests to determine the extent of the impaired cognition and to measure changes over time. The type of test used is based on the ability of the client.[18]

A common neuropsychological test is the Mini-Mental State Exam (MMSE). The MMSE assesses five major cognitive areas including orientation, registration, attention and calculation, recall, and speech-language-reading.

The MMSE test requires the ability to read. For clients who are unable to read, a test called the set test may be used. In the set test, the client is asked to name ten items in each of four sets: fruits, animals, colors, and twins. The client receives one point for each item out of 40 possible points. A score above 25 indicates the client does not have dementia.

View an example MMSE test: The Mini Mental State Examination (MMSE) PDF

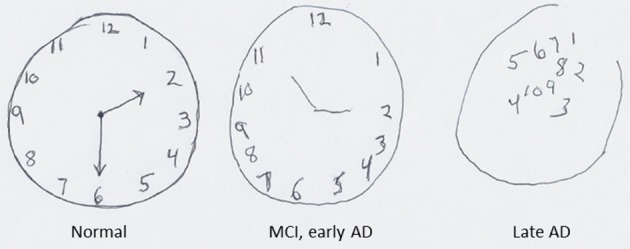

Another cognitive screening tool that does not require the ability to read is the clock drawing test. The client is provided with a piece of paper with a pre-drawn circle approximately 10 cm in diameter and told that the circle represents the face of a clock. The person is asked to write numbers within the circle so that it looks like a clock and then add arms to the clock to show a desired time, such as “ten minutes after eleven.” See Figure 9.15[19] for an illustration of the clock drawing test with results from clients with different states of AD.

Laboratory and Diagnostic Tests

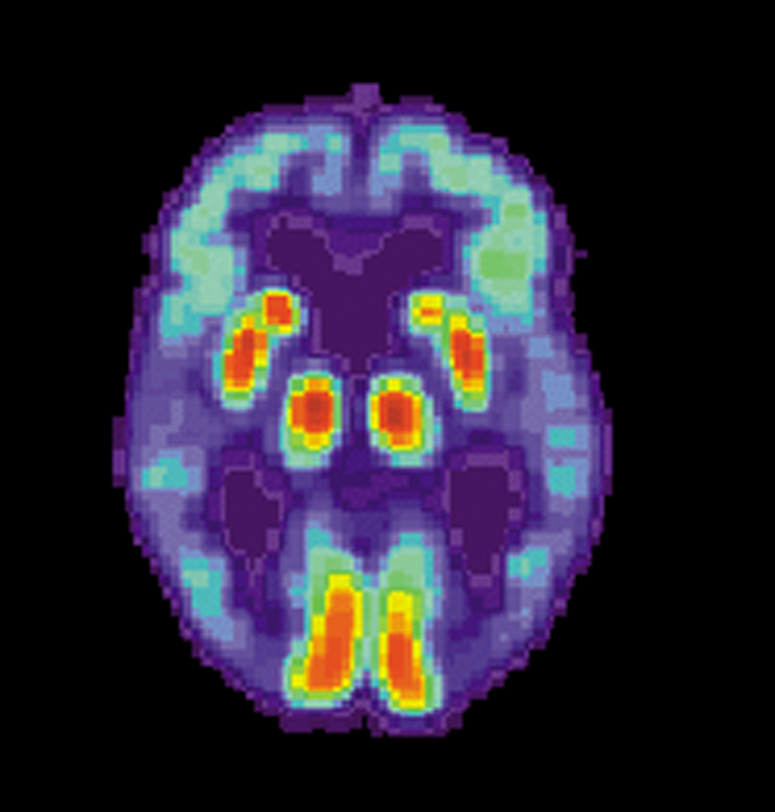

A definitive diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease can only be made by autopsy and examination of brain tissue showing the presence of neurofibrillary tangles and neuritic plaques. However, recent progress has been made in measuring these brain changes with diagnostic tests. For example, abnormal levels of beta-amyloid and tau can be measured in cerebrospinal fluid (CSF), and positron emission tomography (PET) can produce images showing where beta-amyloid and tau have accumulated in the brain.[20],[21] See Figure 9.16[22] for an image of a PET scan of a person with Alzheimer’s disease showing loss of function in the temporal lobe.

Blood Tests

Vitamin B12 and thyroid hormone blood tests are often performed to rule out other causes of cognitive impairment. Liver function blood levels may also be performed to rule out encephalopathy caused by liver disease.

Nursing Diagnoses

Common nursing diagnoses for clients with AD include the following[23]:

- Disturbed Thought Process

- Chronic Confusion

- Impaired Memory

- Risk for Falls

- Risk for Injury

- Impaired Verbal Communication

- Anxiety

- Chronic Sorrow

- Self-Care Deficit: Bathing

- Self-Care Deficit: Dressing

- Self-Care Deficit: Feeding

- Impaired Physical Mobility

- Disturbed Sleep Pattern

- Social Isolation

- Caregiver Role Strain

Outcome Identification

The overall goal for clients with Alzheimer’s disease is to maintain a safe environment due to cognitive impairment with a high risk for falls and injury. Other goals include promoting independence in self-care activities, reducing anxiety and agitation, improving communication and socialization, promoting adequate nutrition and sleep, and providing caregiver support.

Sample outcome criteria include the following:

- The client will maintain optimal memory and cognitive function for as long as possible to maintain their quality of life.

- The client will remain free from injury and accidents at home by providing a safe environment.

- The client will maintain adequate nutritional intake to support general health and well-being.

- The client will engage in social activities to promote effective coping with chronic illness.

- Caregivers will identify three stress-reduction techniques after a teaching session.

Interventions

Medical Interventions

Although there is no cure for AD, there are treatment options available that may slow the progression of the disease and manage common symptoms. Collaboration with occupational and physical therapists can help the client retain general strength and remain as independent as possible with performing their activities of daily living. Incorporating adaptive devices such as walkers, grab bars, commodes, and eating utensils can assist clients to maintain as much independence as possible with toileting, bathing, ambulating, and eating. Referrals to dieticians or nutritionists can also help modify their diet with nutritional supplements to support optimal physiological health.

Medication Therapy

There are two types of medication classes used to treat Alzheimer’s disease: those that slow disease progression by targeting the underlying biology of the disease and those that help manage symptoms of the disease.

- Amyloid-targeting agents work by attaching to and removing beta-amyloid, the protein that accumulates into plaques. Different medications work differently at different stages of plaque development, but they all work best during the early stages of the disease, providing clients more time to participate in daily life activities independently.

- Cholinesterase inhibitors treat symptoms related to memory, thinking, language, judgment, and other thought processes. They prevent the breakdown of acetylcholine and support communication between nerve cells.

- Glutamate regulators improve memory, attention, reasoning, language, and ability to perform simple tasks. The medications work by regulating the activity of glutamate, which assists in helping the brain process information.

- Orexin receptor antagonists are approved to treat symptoms of insomnia associated with AD. This medication inhibits the activity of orexin, a neurotransmitter involved in the sleep-wake cycle.

- Psychotropic drugs are reserved for clients with AD who have dementia psychosis. These drugs are considered chemical restraints because they decrease mobility and the client’s self-management ability. For example, atypical antipsychotics such as risperidone and olanzapine and anticonvulsants such as carbamazepine and valproic acid may be prescribed for severe aggressive agitation. Agency policy and The Joint Commission’s safety standards should be followed concerning the use of these chemical restraints.

Medications used to treat Alzheimer’s disease are summarized in Table 9.5a and Table 9.5b.[24]

Table 9.5a. Medications That Slow the Progression of the Disease

Temporary swelling in the brain, headaches, dizziness, nausea, vision changes, and falls. People with genetic risk factors are at higher risk for brain swelling and should be screened prior to its use.

| Medications | Side Effects | Nursing Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Amyloid-targeting Agents

Aducanumab Lecanemab |

Table 9.5b. Medication to Treat Symptoms

| Medications | Side Effects | Nursing Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Cognitive Symptoms

Cholinesterase Inhibitors Donepezil (approved for all stages of AD) Rivastigmine and galantamine (approved for mild to moderate AD) |

Generally well-tolerated. Common side effects include nausea, vomiting, loss of appetite, and increased frequency of bowel movements. May cause bradycardia. |

Monitor heart rate and for dizziness. Use cautiously in clients with heart disease. |

| Cognitive Symptoms

Glutamate Regulators Memantine |

Side effects include headache, confusion, dizziness, and constipation. |

Implement fall precautions and a bowel management program as indicated. |

| Sleep Symptoms

Orexin Receptor Antagonists Suvorexant |

Risk for impaired alertness and motor coordination, worsening of depression or suicidal thinking, sleep paralysis, and compromised respiratory function. |

Monitor for suicidal ideation and respiratory distress. |

| Psychosis Symptoms: Severe Aggressive Agitation

Atypical antipsychotics: Risperidone and olanzapine Anticonvulsants: Carbamazepine and valproic acid |

Decrease mobility and the client’s self-management ability. |

Considered chemical restraints; follow agency policy and The Joint Commission’s safety standards. |

Read more information about donepezil in the “Acetylcholinesterase Inhibitors” section of the “Autonomic Nervous System” chapter of Open RN Nursing Pharmacology, 2e.

Read more information about “Antipsychotics” and “Anticonvulsants” in the “Central Nervous System” chapter of Open RN Nursing Pharmacology, 2e.

Alternative Treatments

In the United States there are many non-FDA approved herbal remedies and dietary supplements advertised to delay or prevent AD. Although eating a healthy diet may lower the risk of cognitive decline and dementia, there are no proven supplements or foods that prevent or treat the disease. As with all supplements, the health care provider should be aware of their use to prevent side effects or interactions with prescribed medications.

Nursing Interventions

Nursing interventions for clients with AD focus on maintaining safety, optimal functioning, and independence in self-care activities for as long as possible. Depending on the symptoms and stage(s) the client is experiencing, interventions are tailored to the client’s situational needs. Other interventions include providing cognitive and memory therapy, reducing anxiety and agitation, improving communication, promoting adequate nutrition, supporting bowel/bladder continence, balancing rest and activity, and educating/supporting family caregivers.

Many factors, including physical illness and environmental variables, can exacerbate or worsen the manifestations of AD. Clients with AD typically have other health problems such as renal disorders, arthritis, cardiovascular disease, and pulmonary conditions, as well as changes with hearing and vision. Managing these other problems as part of the nursing plan of care can improve the client’s functional ability. See Table 9.5c for a summary of nursing interventions for clients with AD.

Table 9.5c. Nursing Interventions for Clients with Alzheimer’s Disease

| Manage Cognitive Dysfunction |

|---|

|

| Prevent Injuries or Falls |

|

| Manage Incontinence |

|

| Promote Nutrition |

|

| Balance Activity and Rest |

|

| Promote Communication |

|

When clients with Alzheimer’s disease are hospitalized, the unfamiliar surroundings and routine can worsen their confusion, resulting in combative behaviors. See the following box for specific nursing interventions for hospitalized clients with AD.

Nursing Interventions in Acute Care Settings for Clients with Alzheimer’s Disease[25]

- Place the client in an area that allows for maximum observation.

- Provide appropriate supervision with frequent vision checks, especially during shift change.

- Use family members, friends, volunteers, or hospital sitters as needed for agitation.

- Identify clients who are most at risk for wandering upon admission.

- Avoid changing rooms to prevent increased confusion.

- Assess and treat for pain; use the PAINAD scale as appropriate.

- Keep the client away from stairs and elevators.

- Use reorientation or validation therapy as appropriate.

- Provide frequent toileting and incontinence care.

- Use bed and/or chair alarms and video monitoring, as available.

- Prevent overstimulation, excessive noise, and uninterrupted sleep as much as possible.

- Use soft music and nonglare lighting if possible.

- Avoid physical and/or chemical restraints.

Read more about the PAINAD scale at MD Calc’s Pain Assessment in Advanced Dementia Scale (PAINAD) webpage

Health Teaching

In early stages of AD, the client may be cared for at home by family members with little necessity for external interventions. However, a referral to a case manager should be made soon after the diagnosis. The case manager performs a need assessment and helps provide health care resources throughout the continuum of care as the disease progresses.

Family caregivers who provide care for loved ones with moderate to severe AD can experience stress and burnout that can affect their personal health. See the following box for health promotion strategies and teaching tips for caregivers.

Strategies to Reduce Family Member/Caregiver Stress[26]

- Develop and maintain realistic expectations for oneself and the loved one with Alzheimer’s disease.

- Use resources from the Alzheimer’s Association, including support groups or the toll-free hotline.

- Explore options for alternative health care settings early in the disease process for possible use later.

- Early in the disease process, establish advance directives for the client.

- Set aside time each day for rest away from the person with AD, if possible.

- Engage in self-care activities such as leisure time, hobbies, exercise, and relaxation techniques.

- Try to find positive aspects of the situation daily.

- Seek respite care.

- Seek out pastoral care or spiritual counseling, as desired.

Review caregiver resources available at the Alzheimer’s Association’s website.

Evaluation

Evaluation of client outcomes refers to the process of determining whether or not client outcomes were met by the indicated time frame. This is done by reevaluating the client as a whole and determining if their outcomes have been met, partially met, or not met. If the client outcomes were not met in their entirety, the care plan should be revised and reimplemented. Evaluation of outcomes should occur each time the nurse assesses the client, examines new laboratory or diagnostic data, or interacts with a family member or other member of the client’s interdisciplinary team.

- Alzheimer’s Association. (2023, March). Veterans and Alzheimer’s disease. https://portal.alzimpact.org/media/serve/id/5b219da2644f5 ↵

- Alzheimer’s Association. (2023, March). Veterans and Alzheimer’s disease. https://portal.alzimpact.org/media/serve/id/5b219da2644f5 ↵

- “Brain-ALZH.png” by Garrondo is licensed in the Public Domain. ↵

- “Alzheimers_brain.jpg” by National Institutes of Health is licensed in the Public Domain. ↵

- “TANGLES_HIGH.jpg” by ADEAR: “Alzheimer's Disease Education and Referral Center, a service of the National Institute on Aging" is licensed in the Public Domain. ↵

- Alzheimer’s Association. (2023, March). Veterans and Alzheimer’s disease. https://portal.alzimpact.org/media/serve/id/5b219da2644f5 ↵

- Harvard Health Publishing. (2021, March 2). Two types of drugs you may want to avoid for the sake of your brain. https://www.health.harvard.edu/mind-and-mood/two-types-of-drugs-you-may-want-to-avoid-for-the-sake-of-your-brain ↵

- Jaynes, M., & Kumar, A. B. (2018). The risks of long-term use of proton pump inhibitors: A critical review. Therapeutic Advances in Drug Safety. https://doi.org/10.1177/2042098618809927 ↵

- Alzheimer’s Association. (2023, March). Veterans and Alzheimer’s disease. https://portal.alzimpact.org/media/serve/id/5b219da2644f5 ↵

- Alzheimer’s Association. (n.d.). New IDEAS study. https://www.alz.org/research/new-ideas-study ↵

- Alzheimer’s Association. (2023, March). Veterans and Alzheimer’s disease. https://portal.alzimpact.org/media/serve/id/5b219da2644f5 ↵

- Alzheimer’s Association. (2023, March). Veterans and Alzheimer’s disease. https://portal.alzimpact.org/media/serve/id/5b219da2644f5 ↵

- Lennon, J. C., Aita, S. L., Bene V. A. D., Rhoads, T., Resch, Z. J., Eloi, J. M., & Walker, K. A. (2021). Black and White individuals differ in dementia prevalence, risk factors, and symptomatic presentation. Alzheimer’s & Dementia. 18(8), 1461-1471. https://doi.org/10.1002/alz.12509 ↵

- Alzheimer’s Association. (2023, March). Veterans and Alzheimer’s disease. https://portal.alzimpact.org/media/serve/id/5b219da2644f5 ↵

- Alzheimer’s Association. (n.d.). New IDEAS study. https://www.alz.org/research/new-ideas-study ↵

- Alzheimer’s Association. (2023, March). Veterans and Alzheimer’s disease. https://portal.alzimpact.org/media/serve/id/5b219da2644f5 ↵

- Alzheimer’s Association. (2023, March). Veterans and Alzheimer’s disease. https://portal.alzimpact.org/media/serve/id/5b219da2644f5 ↵

- Alzheimer Disease (Nursing) by Kumar, Sidhu, Goyal, Tsao, & Doerr is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 ↵

- “Superior-pattern-processing-is-the-essence-of-the-evolved-human-brain-fnins-08-00265-g0004.jpg” by Mattson M is licensed under CC BY 3.0 ↵

- Lennon, J. C., Aita, S. L., Bene V. A. D., Rhoads, T., Resch, Z. J., Eloi, J. M., & Walker, K. A. (2021). Black and White individuals differ in dementia prevalence, risk factors, and symptomatic presentation. Alzheimer’s & Dementia. 18(8), 1461-1471. https://doi.org/10.1002/alz.12509 ↵

- Alzheimer’s Association. (2023, March). Veterans and Alzheimer’s disease. https://portal.alzimpact.org/media/serve/id/5b219da2644f5 ↵

- Enter your footnote content here. ↵

- Herdman, T. H., Kamitsuru, S., & Lopes, C. T. (Eds.). (2020). Nursing diagnoses: Definitions and classification, 2021-2023 (12th ed.). Thieme. ↵

- Alzheimer’s Association. (n.d.). Medications for memory, cognition, and dementia-related behaviors. https://www.alz.org/alzheimers-dementia/treatments/medications-for-memory ↵

- Quality and Safety Education for Nurses. (2023, April 23). Geriatrics. https://www.qsen.org/post/geriatrics ↵

- Acute Stroke (Nursing) by Tadi, Lui, & Budd is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 ↵

A general term that refers to a decline in cognitive ability severe enough to interfere with a person’s ability to complete their activities of daily living.

The most common type of dementia, accounting for at least two thirds of cases of dementia in people aged 65 and older.

Refers to the brain’s ability to make flexible and efficient use of networks of neuron-to-neuron connections that enable a person to continue to carry out cognitive tasks despite degenerative brain changes.

Increased confusion at night or when lighting is inadequate.

A common neuropsychological test which assesses five major cognitive areas including orientation, registration, attention and calculation, recall, and speech-language-reading.

The client is asked to name ten items in each of four sets: fruits, animals, colors, and twins.

A neurological test in which the client is provided with a piece of paper with a pre drawn circle approximately 10 cm in diameter and told that the circle represents the face of a clock. The person is asked to write numbers within the circle so that it looks like a clock and then add arms to the clock to show a desired time.