9.6 Parkinson’s Disease

Parkinson’s disease (PD) is a common, progressive neurological movement disorder of older adults that eventually leads to disability. Parkinson’s disease can be divided into five stages:

- Stage 1 (Initial): Unilateral limb involvement, hand and arm trembling, and mild weakness

- Stage 2 (Mild Stage): Bilateral limb involvement, resting tremor, bradykinesia (slow, shuffling gait), and mask-like facial expression

- Stage 3 (Moderate): Postural instability, increased gait irregularities, and pill-rolling tremor

- Stage 4 (Severe): Akinesia (the inability to voluntarily move muscles) and rigidity

- Stage 5 (Total Dependence): Total reliance on caregivers for ADLs

Pathophysiology

Parkinson’s disease is associated with decreased levels of dopamine. In normal brain activity, the excitatory neurotransmitter acetylcholine and the inhibitory neurotransmitter dopamine relay messages to the motor centers in the brain where control of motor movement occurs. When these neurotransmitters are balanced, there is refined and coordinated movement, such as picking up a pencil and writing. However, decreased dopamine levels cause an imbalance with the excitatory neurotransmitter acetylcholine, affecting voluntary movement. The clinical symptoms of PD typically do not appear until dopamine levels decrease by 80%. The loss of dopamine also reduces the sympathetic nervous system stimulation of the heart and blood vessels, which can result in orthostatic hypotension, drooling, nocturia, and other autonomic symptoms.

Risk Factors

The cause of Parkinson’s disease is not known, but risk factors include genetic predisposition, viral infections, atherosclerosis, head trauma, long-term use of antipsychotic medications, and environmental exposures. PD is typically diagnosed in clients in their sixties or seventies, but in some cases it can occur as early as 30 years of age. PD tends to affect more men than women, and there is increased risk with family history in first-degree relatives.

Health Disparities Related to Parkinson Disease

A recent study identified crucial gaps in care for people diagnosed with Parkinson’s disease in the United States. The greatest disparities in care occur in women, people of color (those who identify as Asian, Black, Hispanic and Native American), and residents of rural areas. These disparities include lack of access to movement disorder specialists (expertly trained neurologists who can tailor treatments to each client), treatment of associated depression from mental health professionals, and access to supplemental therapies such as physical and occupational therapy, speech-language therapy, and mental health services.[1]

Assessment

PD typically has a gradual onset with progression of symptoms. Four primary symptoms of PD include the following[2]:

- Resting tremor

- Muscle rigidity

- Bradykinesia or akinesia

- Postural instability

Although PD is not a form of dementia, cognitive changes can occur later in the disease process, such as dementia or psychosis.

The most common reason people initially seek medical care is due to a resting tremor. Resting tremors disappear with purposeful, voluntary movement, but become apparent when the person’s extremities are motionless. Eventually, the tremor becomes a repetitive, constant, slow-turning motion between the forearm, hand, and thumb, commonly known as pill-rolling, as if the person is rolling a pill between the fingers. The pill-rolling tremor is present at rest and often increases as the client walks, concentrates, or experiences anxiety.[3]

View a supplementary YouTube video[4] on pill rolling: Pill Rolling Resting Tremor | Parkinson Disease.

Muscle rigidity refers to resistance to passive limb movement. Cogwheel rigidity is seen frequently with PD, characterized by a jerky rhythmic tone on passive muscle stretching. The muscles remain constantly tense and contracted so that the person may feel achy and stiff. The rigidity becomes evident when another person tries to move the individual’s arm, which will move only in short, jerky movements. Muscle rigidity is present early in the disease and progresses over time, causing the client to require assistance with ADLs and ambulation. The facial muscles may also experience muscle rigidity, causing a mask-like appearance with wide-open, fixed, staring eyes. In later stages of PD, muscle rigidity can lead to difficulty with chewing and swallowing as the pharyngeal muscles become involved, placing the client at risk for aspiration and malnutrition. Uncontrolled changes in speech patterns are also common symptoms. Clients may speak very softly, slur or repeat words, hesitate before speaking, project a monotone voice, or exhibit a rapid speech pattern.[5]

Bradykinesia refers to slowness of initiation of movement, and akinesia refers to a lack of voluntary movement. For example, clients may have difficulty initiating movements, such as rising from a chair to stand.[6]

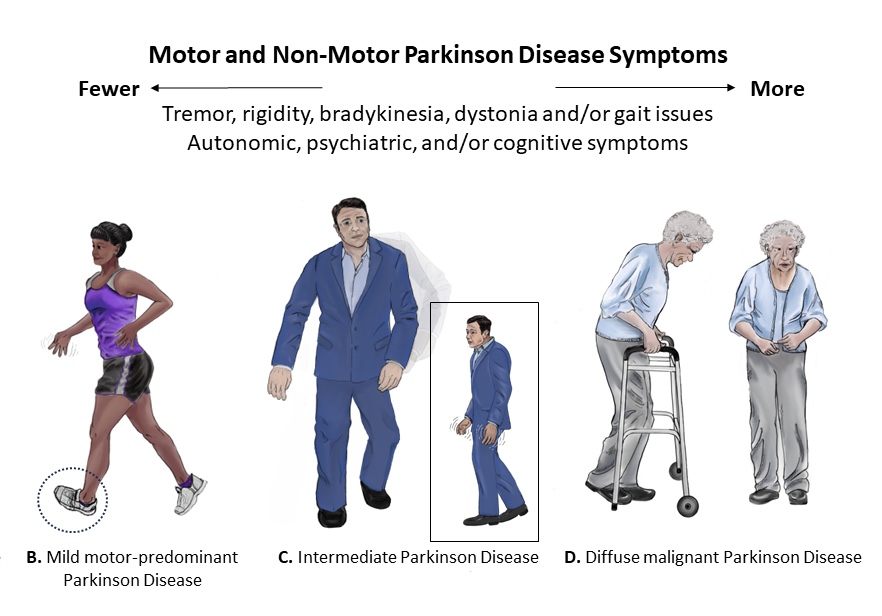

Postural disturbances become apparent as loss of reflexes occur. A client with PD typically stands with their head bent forward and walks with a propulsive gait. This characteristic posture is caused by the forward flexion of the neck, hips, knees, and elbows. They tend to compensate for this postural disturbance by moving their feet forward under the body’s center of gravity, referred to as shuffling gait. Clients with PD are at high risk for falls due to this postural disturbance and lack of balance.[7] See Figure 9.17[8] for illustrations of postural disturbances of clients with various stages of PD.

View an animation[9] of the characteristic gait of a person with Parkinson’s disease: Abnormal Gait Exam: Parkinsonian Gait Demonstration.

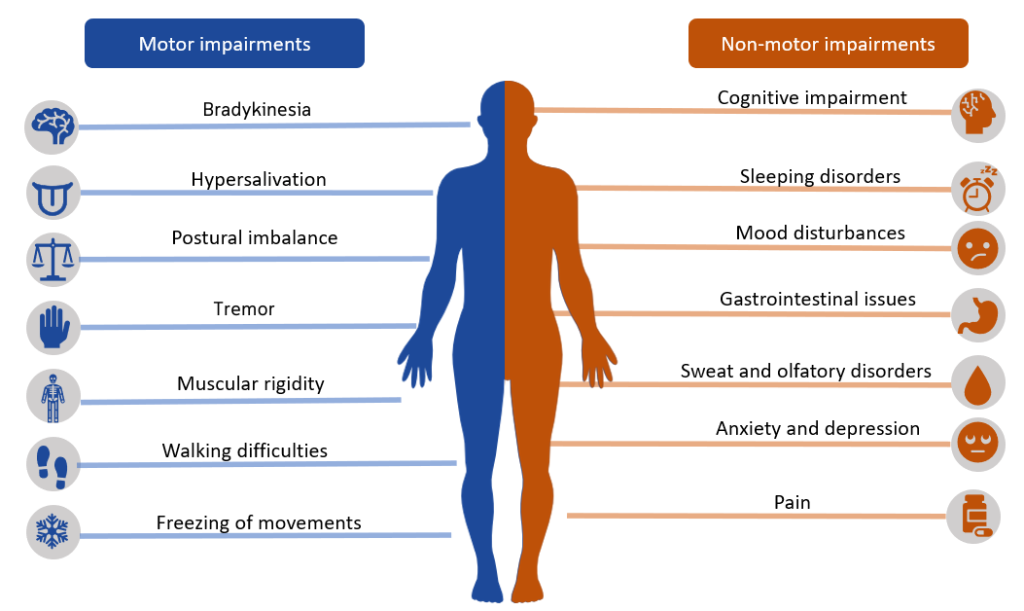

In addition to the four classic symptoms of PD, autonomic symptoms such as excessive sweating, orthostatic hypotension, urinary retention, constipation, and sexual dysfunction may also occur. Mood and personality changes may occur, such as depression, psychosis, dementia, sleep disturbances, and auditory or visual hallucinations. Cognitive changes can also affect the judgment and decision-making of a person with PD. See Figure 9.18[10] for an illustration of motor and nonmotor impairments that may occur in clients with Parkinson’s disease.

Common Labs and Diagnostic Tests

There are no diagnostic tests that specifically diagnose Parkinson disease. Providers diagnose PD if the client has at least two of the four cardinal symptoms previously discussed. Other potential neurologic diseases are eliminated with the following tests:

- Blood tests may be ordered to rule out other disorders that may be causing the symptoms.

- Single photon emission computed tomography (SPECT) may be ordered to rule out other nervous system disorders. It can also detect a loss of dopamine-producing neurons.

- Analysis of cerebrospinal fluid may show a decrease in dopamine levels.

- Brain scans such as CTs and MRIs are performed to rule out other nervous system disorders.

Nursing Diagnoses

Priority nursing diagnoses for clients with PD focus on impaired mobility, cognitive function, communication, and gastrointestinal function. Common nursing diagnoses include the following[11]:

- Impaired Physical Mobility

- Impaired Swallowing

- Chronic Confusion

- Impaired Memory

- Activity Intolerance

- Impaired Verbal Communication

- Risk for Falls

- Constipation

Outcome Identification

Overall goals for clients with Parkinson’s disease include improving mobility, functioning, and independence in performing ADLs; preventing falls and injury; promoting optimal bowel elimination; maintaining acceptable nutritional status; achieving effective communication and positive coping mechanisms; and teaching the client and their family on the disease process and self-care strategies to manage symptoms and improve the overall quality of life. Sample outcome criteria include the following:

- The client will remain free of complications related to immobility.

- The client will maintain adequate nutritional intake with a BMI in the normal range.

- The client will not experience aspiration.

- The client will remain free of injuries.

- The client will use methods of communication to make needs known to caregivers after the teaching session.

- The client will verbalize three strategies to effectively cope with chronic disease after the teaching session.

Interventions

Medical Interventions

Because there is no cure for PD, medical management focuses on alleviating symptoms and improving the client’s quality of life. Medical interventions are tailored to an individual’s symptoms, disease severity, age, and lifestyle.

Medication Therapy

Medications are the most common medical intervention, with the goal to increase dopamine levels or mimic dopamine effects in the brain. Medications must be closely monitored to prevent long-term side effects and complications.

Levodopa is the most effective medication used to treat PD. Levodopa is converted to dopamine in the brain and provides some symptom relief. Levodopa is commonly prescribed in combination with carbidopa to maximize its benefits. These medications are most beneficial in the first few years of treatment. However, over time, their benefits begin to lessen, and side effects such as confusion, hallucinations, depression, and sleep disturbances can develop.

After approximately 5 to 10 years of chronic use, the client may develop undesirable side effects from these medications referred to as dyskinesia. Dyskinesia refers to abnormal involuntary movements such as facial grimacing, rhythmic jerking movements of hands, lip-smacking, and head bobbing. Clients on chronic medications are also at risk for drug tolerance, where therapeutic effects do not last as long as they did previously. Treatment of dyskinesia involves reducing the dose, changing the drug or frequency of administration, or requesting a drug holiday. During a drug holiday, the client does not receive any medication for PD for up to ten days. Additional medications such as baclofen for muscle spasms or sublingual atropine for excessive drooling may be administered. During the drug holiday, the client is closely monitored for dyskinesia and PD symptoms, and the symptoms are documented.

Other medications prescribed for symptom relief include MAO-B inhibitors, anticholinergics, antivirals, dopamine agonists, COMT inhibitors, and antidepressants. See Table 9.6 for an overview of medications used to treat PD.

Table 9.6. Antiparkinson Medications[12]

| Medication | Nursing Considerations and Side Effects |

|---|---|

| Antiparkinson’s Agent

Carbidopa/Levodopa |

Initial side effects of levodopa-carbidopa may include nausea, low blood pressure, restlessness, and drowsiness.

Side effects of long-term or extended use of levodopa may include hallucinations, psychosis, and dyskinesia. |

| Anticholinergic Therapy

Trihexyphenidyl Hydrochloride Benztropine Mesylate |

Controls tremor and assists with drooling by counteracting the neurotransmitter acetylcholine.

Typically, poorly tolerated in older adults. May increase intraocular pressure. Male clients with BPH are monitored for urinary retention. |

| Antiviral Therapy

Amantadine Hydrochloride |

Improves symptoms related to akinesia, and tremor.

Usually well-tolerated, but side effects may include mood changes, confusion, depression, hallucinations, orthostatic hypotension, and headache. |

| Dopamine Agonists

Bromocriptine Mesylate Pergolide Ropinirole Hydrochloride Pramipexole |

Useful before initiating carbidopa or levodopa therapy or when added after carbidopa or levodopa lose their effectiveness.

Adverse effects include lightheadedness, hypotension, diarrhea, and psychiatric effects. |

| Catechol-O-Methyltransferase (COMT) Inhibitors

Entacapone Tolcapone |

May increase duration of action when given in combination with carbidopa or levodopa.

Block an enzyme that breaks down levodopa, making it more available to convert to dopamine in the brain. |

| Tricyclic Antidepressants

Amitriptyline Hydrochloride |

Used for the anticholinergic and antidepressant effects.

Dosing is usually ⅓ to ½ the typical dose in clients with PD. |

| Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitors (SSRIs)

Fluoxetine Hydrochloride |

Effective for treating depression but may aggravate symptoms of Parkinson’s disease. |

| Atypical Antidepressants

Bupropion Hydrochloride |

Effective for treating depression but may aggravate symptoms of Parkinson’s disease. |

| Monoamine Oxidase Inhibitors (MAOIs)

Selegiline Rasagiline Zydis Selegiline HCL |

Used in combination with a dopamine agonist to postpone the initiation of carbidopa or levodopa therapy. Adverse effects are similar to that of levodopa.

Teach clients taking MAOIs to avoid foods, beverages, and drugs that contain tyramine, such as cheese; aged, smoked, or cured foods; and not to drink beer or red wine to prevent headache and life-threatening hypertension. If the drug is discontinued, follow restrictions for 14 days after the last dose. |

Physical, Occupational, and Speech Therapy

Because shuffling gait, postural instability, and other muscle problems are major problems for clients with PD, collaboration with physical and occupational therapists is important in early stages of the disease. Physical therapists plan and implement programs to prevent falling and maintain flexibility and mobility through range-of-motion exercises, muscle stretching, and physical activity. Teaching clients how to safely use ambulatory assistive devices is also provided. Occupational therapists teach clients how to use adaptive devices, such as specialized eating utensils. These rehabilitation services encourage clients to participate as much as possible in their ADLs while ensuring the environment is safe.

Speech and language pathologists (SLP) help treat clients with speech and swallowing difficulties. SLPs teach clients how to perform exercises to strengthen the muscles used for swallowing, speaking, and breathing. Depending on the client’s level of functioning, the SLP develops a communication plan and assists with alternative methods of communication such as a communication board, mechanical voice synthesizer, computer, or handheld mobile device.

Surgical Management

Surgery may be performed when medications fail to provide symptom management. Common surgeries are stereotactic pallidotomy and deep brain stimulation. During stereotactic pallidotomy, a probe is placed in the globus pallidus portion of the brain, destroying specific tissue and creating scar tissue. The scar tissue interrupts the overactive nerve signal transmission, reducing the brain activity in that area and helping to treat rigidity and reducing tremor.[13]

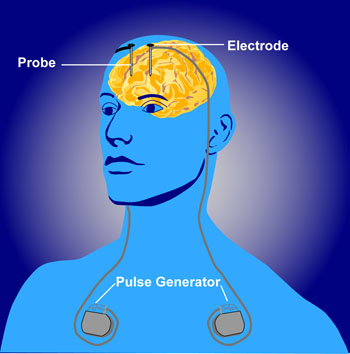

Deep brain stimulation involves implanting electrodes in the brain that are attached to a pulse generator. The generator device is placed under the skin and delivers an electric current to decrease dyskinesias and reduce the need for dopamine precursor medications. See Figure 9.19[14] for an illustration of deep brain stimulation.

Nutritional Management

Consultation with a registered dietician or nutritionist is helpful to evaluate the client’s food intake and their ability to swallow. If dysphagia is present, the SLP and dietician collaborate on the most appropriate diet for the client, such as a soft diet with thickened liquids or incorporation of supplement shakes. If the client is experiencing constipation, the dietician can also help adjust the diet.

Nursing Interventions

Nursing interventions follow a holistic approach when caring for clients with PD and play a crucial role in enhancing their quality of life. Interventions focus on enhancing mobility and self-care activities, improving communication, assisting with optimal nutrition intake, facilitating swallowing, and supporting effective coping strategies. Specific nursing interventions are summarized in the following box.

Nursing Interventions for Clients with Parkinson’s Disease[15]

- Administer prescribed medications on schedule to maintain consistent therapeutic levels. Monitor for side effects, especially orthostatic hypotension, acute confusion, and hallucinations.

- Initiate fall precautions according to agency policy.

- Allow the client time to perform ADLs and provide assistance only as needed to promote independence.

- Implement interventions that prevent complications related to immobility such as pressure injuries, constipation, and contractures.

- Monitor the client’s ability to chew and swallow, as well their food and fluid intake.

- Schedule appointments and activities late in morning or when clients are at their optimal levels of functioning to avoid rushing or fatigue.

- Collaborate with a dietician to provide nutritional, high-calorie foods to maintain strength and well-being.

- Allow the client extra time to respond to questions to promote effective communication. Encourage clients to speak slowly and clearly. Use alternative forms of communication, such as communication boards, as indicated by SLP.

- Collaborate with physical and occupational therapy to promote optimal mobility, physical activity, and independence in completing their ADLs.

- Focus on the client’s strengths, recognizing that PD can lower one’s self-esteem.

- Monitor for new signs of depression, anxiety, impaired cognition, insomnia, and sleep disturbances.

Health Teaching

Nurses provide health teaching to the client and their family members on the following topics:

- Instruct on safe medication administration and promptly report any adverse effects of medication, such as acute confusion and hallucinations.

- Teach how to prevent falls (remove rugs and clutter, use assistive devices).

- Teach the importance of focusing on the client’s abilities and strengths and offer positive reinforcement when goals are met.

- Encourage the family and client to work collaboratively with the rehabilitation team to maintain optimal level of functioning.

- Provide education regarding symptom management, for example, increasing fluids and fiber for issues with constipation.

- Instruct on sleep enhancement such as avoidance of alcohol and caffeine, darkening lighting, and bedtime routine.

- Teach family, along with the dietician, about healthy and appropriate food choices to promote optimal nutrition.

- Encourage family and caregivers that many times the client cannot control symptoms of anxiety or depression and to seek assistance from health care providers, case managers, and support groups.

- Refer clients and family to local and national Parkinson’s disease organizations to facilitate resources available for caregiver strain.

Caring for a client with PD can pose unique challenges for family members. It is helpful to establish a case manager to ensure the psychosocial and physical needs are addressed. A case manager or social worker can also assist the family with financial and health insurance issues, as well as prepare for respite or long-term care.

Evaluation

Evaluation of client outcomes refers to the process of determining whether or not client outcomes were met by the indicated time frame. This is done by reevaluating the client as a whole and determining if their outcomes have been met, partially met, or not met. If the client outcomes were not met in their entirety, the care plan should be revised and reimplemented. Evaluation of outcomes should occur each time the nurse assesses the client, examines new laboratory or diagnostic data, or interacts with a family member or other member of the client’s interdisciplinary team.

![]() RN Recap: Parkinson’s Disease

RN Recap: Parkinson’s Disease

View a brief YouTube video overview of Parkinson’s disease[16]:

- Parkinson’s Foundation. (2023). New Medicare study finds critical gaps and disparities in access to Parkinson’s care. https://www.parkinson.org/blog/awareness/care-access-disparities ↵

- National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke. (n.d.). Parkinson’s disease. https://www.ninds.nih.gov/health-information/disorders/parkinsons-disease ↵

- National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke. (n.d.). Parkinson’s disease. https://www.ninds.nih.gov/health-information/disorders/parkinsons-disease ↵

- Extensive Medicine. (2023, December 19). Pill rolling resting tremor | Parkinson disease. [Video]. YouTube. All rights reserved. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=7Q1G3llwAPs ↵

- National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke. (n.d.). Parkinson’s disease. https://www.ninds.nih.gov/health-information/disorders/parkinsons-disease ↵

- National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke. (n.d.). Parkinson’s disease. https://www.ninds.nih.gov/health-information/disorders/parkinsons-disease ↵

- National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke. (n.d.). Parkinson’s disease. https://www.ninds.nih.gov/health-information/disorders/parkinsons-disease ↵

- “Modern_Parkinson%27s_Disease_Image_Cropped.jpg" by Erica Rodriguez (artist), Michael S. Okun (author), cropped by User:Dustfreeworld is in the Public Domain. ↵

- “Abnormal_Gait_Exam_Parkinsonian_Gait_Demonstration.gif” by unknown author, via MakeAGIF is in the Public Domain ↵

- "Bradykinesia" by Meredith Pomietlo is a derivative of “Parkinson_disease_symtpoms.png” by CarrotsMitHummus licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0 ↵

- Herdman, T. H., Kamitsuru, S., & Lopes, C. T. (Eds.). (2020). Nursing diagnoses: Definitions and classification, 2021-2023 (12th ed.). Thieme. ↵

- National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke. (n.d.). Parkinson’s disease. https://www.ninds.nih.gov/health-information/disorders/parkinsons-disease ↵

- University of Washington Medicine - Neurological Surgery. (n.d.). Stereotatic treatments for Parkinson’s disease. https://neurosurgery.uw.edu/patients-and-family/what-we-treat/treatments/stereotactic-treatments-parkinsons-disease ↵

- “Deep_brain_stimulation.jpg“ by http://www.nimh.nih.gov/health/topics/brain-stimulation-therapies/brain-stimulation-therapies.shtml is in the Public Domain ↵

- Nunes, S. F. L., Alvarez, A. M., & Valcarenghi, R. V. (2022). Parkinson’s disease in primary health care and nursing care: A scoping review. Revista da Escola de Enfermagem da USP. https://doi.org/10.1590/1980-220x-reeusp-2021-0367 ↵

- Open RN Project. (2024, June 23). Health Alterations - Chapter 9 - Parkinson's disease [Video]. You Tube. CC BY-NC 4.0 https://youtu.be/aeS6N_WwvEc?si=MLKhb_2M4Xl6Qpog ↵

A common, progressive neurological movement disorder of older adults that eventually leads to disability.

Slow, shuffling gait.

The inability to voluntarily move muscles.

Tremors that disappear with purposeful, voluntary movement, but become apparent when the person’s extremities are motionless.

A repetitive, constant, slow-turning motion between the forearm, hand, and thumb.

Resistance to passive limb movement.

Characteristic posture is caused by the forward flexion of the neck, hips, knees, and elbows.

Compensatory movement for postural disturbance in which individuals move their feet forward under the body’s center of gravity.

Uncontrollable movements.