2.2 Basic Concepts Related to Surgery

Urgency of Surgeries

Surgeries may be classified according to their urgency of completion[1]:

- Elective: Elective surgeries are scheduled in advance based on the client’s and surgeon’s preferences. The surgery occurs at a planned time, and client outcomes are not significantly affected if the surgery is delayed. Examples of elective surgeries include tonsillectomy, hernia repair, cataract surgery, scheduled cesarean section, and plastic surgery.

- Urgent: Urgent surgeries are necessary for the client’s health and generally performed within 24 to 48 hours of medical diagnosis of an acute condition. They are performed for acute onset of distressing symptoms or for the survival of limb(s) or organ(s). Examples of urgent surgeries include appendectomy, amputation, and colon resection.

- Emergent: Emergent surgeries are performed immediately to preserve the client’s life. Examples of emergent surgeries include control of hemorrhage, trauma repair, tracheostomy, cardiac bypass for a myocardial infarction (heart attack) if other treatments aren’t effective, or an emergency cesarean section if the mother or baby are in distress.

Types of Surgeries

Surgeries can be categorized based on their purpose, such as diagnostic, curative, restorative, palliative, cosmetic, reconstructive, exploratory, transplantation, neurosurgery, cardiovascular, orthopedic, obstetric and gynecological, and urological procedures.[2] Each category encompasses specific surgical interventions aimed at addressing different medical conditions and client needs. Table 2.2a highlights the diversity and breadth of surgical procedures performed within various specialties.

Table 2.2a. Types of Surgeries[3]

| Surgery Type | Definition | Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Diagnostic surgery | Performed to obtain a definitive diagnosis or to assess the extent of a disease or condition. | Breast biopsy, lymph node biopsy, or endoscopy for gastrointestinal evaluation |

| Curative surgery | Performed to remove or treat the cause of a disease, providing a cure or permanent resolution. | Appendectomy, cholecystectomy (gallbladder removal), or tonsillectomy |

| Reconstructive/Restorative surgery | Aimed at restoring function and improving the quality of life, often involving replacing a body part. | Total knee replacement (TKR), hip replacement, cataract surgery, breast reconstruction following mastectomy, skin grafting for burn clients, or scar revision |

| Palliative surgery | Performed to alleviate symptoms, reduce pain, or improve the client’s comfort without curing the disease. | Tumor debulking or pleurodesis (procedure performed on pleural space to prevent recurrent pleural effusions) |

| Cosmetic surgery | Performed primarily to enhance or alter a person’s appearance. | Liposuction, rhinoplasty (i.e., “nose job”), breast augmentation, or facelift |

| Exploratory surgery | Performed to visualize and inspect internal organs and structures to diagnose or assess health conditions. | Laparoscopy to investigate abdominal pain, arthroscopy to examine joint structures, or endoscopy for gastrointestinal evaluation |

| Transplantation surgery | Performed to replace a failed organ or tissue with a healthy organ or tissue from a donor. | Kidney transplantation, liver transplantation, or heart transplantation |

| Neurosurgery | Performed to treat conditions affecting the nervous system, brain, and spinal cord. | Craniotomy for brain tumor removal, spinal fusion surgery, or deep brain stimulation for Parkinson’s disease |

| Cardiovascular surgery | Performed to treat conditions related to the heart and/or blood vessels, often to improve blood flow. | Coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG), heart valve replacement, or pacemaker implantation |

| Orthopedic surgery | Performed to treat conditions related to the musculoskeletal system, dealing with bones, joints, muscles, ligaments, and tendons. | Fracture fixation, carpal tunnel release, or ligament reconstruction |

| Obstetric/Gynecological surgery | Performed to treat conditions related to pregnancy, childbirth, and female reproductive organs. | Cesarean section, hysterectomy, or tubal ligation |

| Urological surgery | Performed to treat conditions related to the urinary system and male reproductive organs. | Prostatectomy, nephrectomy, or bladder augmentation |

Surgical Settings

There are various surgical settings in which procedures take place, including inpatient and outpatient/ambulatory settings. Other less common areas for surgical procedures include outpatient clinics and emergency departments. No matter the specific surgical setting, nursing staff have a critical role in preparing the client for surgery, providing care during and after the procedure, and ensuring the client has adequate support and resources on discharge.

Inpatient Setting

In an inpatient setting, the client is admitted to the hospital either the day before the surgery or on the same day of the procedure. The client may already be an inpatient receiving treatment for a different condition when surgery becomes necessary. The inpatient setting allows for close monitoring and immediate access to medical care. This setting is suitable for clients who require more extensive surgery, have complex medical conditions, or need postoperative care that necessitates a longer hospital stay.

Outpatient/Ambulatory Surgery

Outpatient/ambulatory surgery includes procedures where the client goes to the surgical area on the day of the surgery and returns home the same day, commonly known as same-day surgery. The outpatient/ambulatory setting provides clients with the convenience of returning home to familiar surroundings and the comfort of being with family members.

Ambulatory surgery procedures may occur in a hospital or a specialized Ambulatory Surgery Center (ASC). ASCs are specialized facilities dedicated to performing outpatient surgeries. ASCs are equipped with the necessary resources and equipment for a wide range of surgical interventions, and they often offer a more streamlined experience compared to traditional hospital settings.

Outpatient procedures may also be performed in Same-Day Surgery Units (SDSU). SDSUs are sections within hospitals or specialized clinics that focus on performing same-day surgeries. These units are specifically designed for clients who require surgery but do not need to stay overnight. They provide a supportive and comfortable environment for clients to undergo their procedures and receive immediate postoperative care before being discharged home.

Outpatient Clinic

In outpatient clinic surgical settings, surgeries are performed in health care facilities where clients receive medical care or procedures without requiring hospitalization. While not exclusively dedicated to surgical procedures, outpatient clinics often perform minor surgeries or procedures that do not require an overnight stay. For example, cyst removal may be performed in an outpatient clinic, and suturing of a minor laceration may occur in urgent care.

Emergency Department (ED)

In certain cases, surgical procedures may need to be performed in the emergency department surgical setting. These are typically urgent or emergency surgeries that are necessary to address critical conditions or life-threatening situations. The ED is equipped to handle immediate surgical interventions to stabilize clients and address acute surgical needs.

Surgical Team

The surgical environment involves a diverse team of highly skilled personnel, each playing a crucial role in ensuring the smooth and safe execution of surgical procedures. Table 2.2b provides an overview of surgical team members and their respective roles and responsibilities.

Table 2.2b. Surgical Team Members[4]

| Staff Member | Role and Responsibilities |

|---|---|

| Surgeon | Leads the surgical team, performs the procedure, and makes critical decisions during the surgery. Explains benefits and risks of surgery to the client and obtains informed consent. Reviews the preoperative history and physical that were performed by the primary health care provider (for planned surgeries) or hospitalist (for urgent/unplanned surgeries) and updates treatment plan as indicated. |

| Anesthesiologist, Certified Nurse Anesthetist (CRNA), and Certified Sedation RN | Anesthesiologists and CRNAs administer general anesthesia, monitor the client’s response to anesthesia, including vital signs and overall well-being during the surgery, and ensure adequate airway and oxygenation. Certified Sedation RNs provide moderate sedation in many settings for clients with lower risk, such as plastic surgery clinics, gastrointestinal (GI) labs, and oral surgery clinics.[5] |

| Surgical Assistant | Surgical assistants, also called surgical first assistants, help surgeons with tasks such as making incisions, placing clamps, and closing surgical sites. A surgical assistant may be another surgeon, physician, physician assistant, resident, advanced practice nurse, or a certified registered nurse first assistant.[6] |

| Surgical Technologist | Surgical technologists prepare operating rooms, arrange equipment, monitor and maintain the sterile field, and help surgeons and first assistants during surgeries.[7] |

| Perioperative Nurse | Sometimes called a surgical or an operating room nurse, this specialized nurse cares for patients before, during, and after surgery. In the operating room, the perioperative nurse may serve as a scrub nurse, selecting and passing instruments and supplies used for the operation, or as a circulating nurse, managing the overall nursing care in the operating room and helping to maintain a safe, comfortable environment.[8]

Specific responsibilities of a perioperative nurse include the following[9]:

Certified perioperative nurse (CNOR) is a specialty certification available for registered nurses working in perioperative services, with most of their time spent intraoperatively. |

Anesthesia

Anesthesia is a critical component of the intraoperative environment. It aims to reduce or temporarily eliminate sensory perception, commonly referred to as “negative sensation.” Anesthetic agents are carefully administered to induce a partial or total loss of sensory perception, which can occur with or without the loss of consciousness.[10]

The main purpose of anesthesia is to achieve several key goals, including blocking nerve impulses, decreasing reflexes, increasing muscle relaxation, and controlling the level of consciousness (LOC) during the surgical procedure. By blocking nerve impulses, anesthesia effectively numbs the sensory nerves, preventing the transmission of pain signals to the brain. This allows the surgical team to perform necessary interventions without causing unnecessary discomfort to the client. Anesthesia also reduces reflexes, thus preventing involuntary movements that could interfere with surgical precision and increase the risk of complications. Muscle relaxation is also essential, as it facilitates surgical access and manipulation while reducing the risk of muscle spasms or other involuntary contractions during the procedure.[11]

One of the crucial aspects of anesthesia is its ability to control the level of consciousness. Depending on the type of surgery and the client’s specific needs, the anesthesia provider can adjust the depth of anesthesia to maintain the desired level of consciousness, ranging from complete unconsciousness (resulting from general anesthesia) to a semiconscious or awake state (resulting from local or regional anesthesia). This level of control allows for optimal client safety and comfort during surgery, as well as a smooth transition to the postoperative phase. Keep in mind that anesthetic agents are metabolized in the liver and excreted in the kidneys, necessitating close monitoring of dosage and client response to ensure their safe and effective use throughout the intraoperative period.[12]

The selection of the most suitable type of anesthesia depends on the client’s medical condition, the complexity of the surgery, the surgeon’s preference, and the client’s comfort and safety. The anesthesia provider works closely with the surgical team to determine the best approach, ensuring a smooth and successful surgical experience for the client.

Various types of anesthesia administration are as follows:

- General Anesthesia: General anesthesia induces a state of unconsciousness and loss of sensation throughout the entire body. It is commonly used for extensive surgeries and procedures where the client needs to be completely unaware and pain-free. General anesthesia can be delivered through inhalation (inhaled gases) or IV injection (intravenous drugs). It requires specialized monitoring and airway management.[13]

- Local Anesthesia: Local anesthesia is used to numb a specific area of the body, typically near the surgical site. It is administered through the injection or application of anesthetic agents directly to the nerves or tissues in the targeted area. Local anesthesia allows clients to remain conscious during the procedure while being free of pain and discomfort in the localized region.[14]

- Regional Anesthesia: Regional anesthesia involves numbing a larger area of the body, such as an entire limb or a section of the body, by blocking the nerve signals in that region. Common types of regional anesthesia include epidural anesthesia (often used for childbirth) and spinal anesthesia (used for lower abdominal and lower extremity surgeries). Regional anesthesia can be combined with sedation to keep the client relaxed and comfortable during the surgery.[15]

- Conscious Sedation: Conscious sedation, also known as moderate sedation or twilight anesthesia, is a state where the client remains conscious but deeply relaxed and pain-free. It is commonly used for minor surgical procedures or diagnostic tests. In conscious sedation, a combination of sedative and analgesic drugs is administered to create a calm and drowsy state.[16]

- Monitored Anesthesia Care (MAC): MAC involves the administration of IV sedation and pain management for clients undergoing certain procedures. The anesthesia provider continuously monitors the client’s vital signs and level of consciousness throughout the procedure.[17]

Each of these types of anesthesia is further described in the following subsections.

The selection of anesthesia is a complex decision-making process, involving the collaboration of the anesthesia provider, surgeon, and other health care team members to ensure the best possible outcome for the client during and after the surgical procedure. The selection of the most appropriate anesthesia type for a surgical procedure involves a comprehensive evaluation of various factors, including the client’s medical condition, the surgical site, safety considerations, pain management goals, and the client’s response to anesthesia. See Table 2.2c for characteristics affecting the selection of anesthesia.

Table 2.2c. Characteristics Affecting the Selection of Anesthesia

| Characteristic | Consideration for Anesthesia Selection |

|---|---|

| Client History & Surgeon Preference | The client’s medical history, current health status, and the surgeon’s preference are taken into account to determine the most appropriate type of anesthesia. |

| Body Area | The location and extent of the surgical procedure influence the choice of anesthesia. General anesthesia is commonly used for extensive surgeries, while local or regional anesthesia may be preferred for specific body areas. |

| Safety Issues | Any preexisting medical conditions, allergies, or potential risks are carefully evaluated to ensure client safety during the administration of anesthesia. |

| Emergent Surgery | In emergency situations, the need for rapid onset and predictable control of anesthesia may influence the type of anesthesia selection. General anesthesia is often chosen for emergency surgeries. |

| Pain Management Goals | The expected postoperative pain level is considered when determining the appropriate anesthesia type. General anesthesia provides complete pain relief, while local or regional anesthesia may require supplementary pain management techniques postoperatively. |

| Fasting Status | The client’s fasting status is crucial for certain types of anesthesia. General anesthesia requires an empty stomach to reduce the risk of aspiration, whereas local anesthesia can be administered regardless of the client’s eating status. |

| Position for Surgery | The client’s surgical position is taken into account; for some procedures, specific positions may limit the choice of anesthesia type. |

| Need for Client Cooperation & Movement | If the surgical procedure requires client cooperation and movement during surgery, a type of anesthesia that allows for a semiconscious or awake state may be preferred. |

| Client’s Previous Response to Anesthesia | The client’s response to previous anesthesia experiences is considered, as some individuals may have specific preferences or adverse reactions to certain anesthesia types. |

General Anesthesia

General anesthesia can be administered through various methods to achieve a controlled state of unconsciousness and analgesia during surgical procedures. The two primary forms of general anesthesia are inhalation and IV injection. Inhalation anesthesia involves the client inhaling volatile agents like sevoflurane or desflurane, which are mixed with oxygen and delivered through a mask or an endotracheal tube. IV injection anesthesia, on the other hand, requires the direct injection of anesthetic agents, such as propofol or thiopental, into the client’s bloodstream.[18]

In modern practice, a common approach to general anesthesia is referred to as balanced anesthesia. This method combines the use of both IV drugs and inhalation agents to achieve specific effects. For instance, thiopental may be used for induction to rapidly induce unconsciousness; nitrous oxide for amnesia to prevent the client from remembering the procedure; morphine for analgesia to manage pain; and pancuronium as a neuromuscular blocking agent for relaxing muscles, facilitating surgical access, and reducing movements during the procedure. Additionally, adjuncts to general anesthetic agents, such as hypnotics, opioid analgesics, and neuromuscular blocking agents are often utilized to enhance the overall anesthesia process. These adjuncts help fine-tune the anesthesia delivery, improve client comfort, and provide a stable and controlled intraoperative environment.[19]

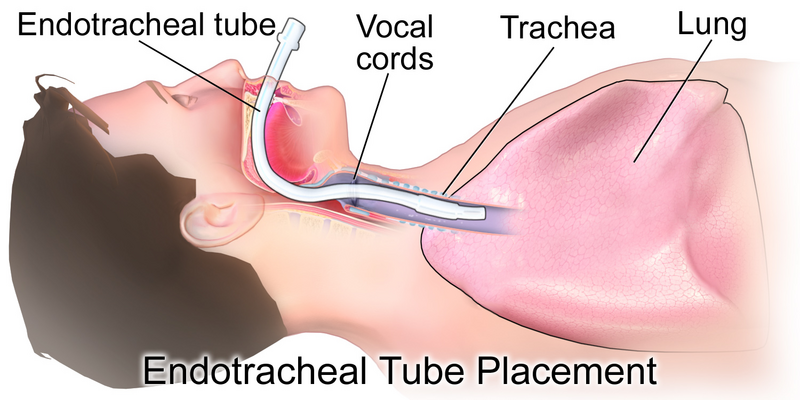

See Figure 2.1[20] for an image of administration of general anesthesia.

Potential Complications From General Anesthesia

Anesthesia is generally considered safe, but complications can occur, varying in severity from minor issues to life-threatening events.

Malignant Hyperthermia

One rare but serious complication is malignant hyperthermia (MH), an acute, inherited muscle disorder triggered by certain drugs used for general anesthesia, specifically inhaled anesthetic agents or the muscle relaxant succinylcholine. MH begins in skeletal muscles exposed to these specific agents, leading to increased calcium levels in muscle cells and heightened muscle metabolism. This results in elevated serum calcium and potassium levels, increased metabolic rate, acidosis, cardiac dysrhythmias, and a high body temperature. MH can manifest at different times during or after anesthesia induction, and early indications include tachycardia, muscle rigidity (particularly of the jaw and upper chest), hypotension, and tachypnea. Detecting MH early is critical for the client’s survival, as it can lead to severe complications and even death. Nurses can help detect a client’s risk for malignant hyperthermia by asking preoperative questions about previous reactions to anesthesia or family history of anesthesia reactions. The most sensitive indication is an unexpected rise in the end-tidal carbon dioxide (ETCO2) level with a decrease in oxygen saturation. A late sign is an extremely elevated body temperature, sometimes reaching temperatures as high as 111.2°F. Immediate action is essential, and the entire surgical team must be prepared to administer dantrolene sodium, a skeletal muscle relaxant, which is considered the drug of choice for treating MH.[21],[22]

View a supplementary YouTube video[23] about noticing and treating malignant hyperthermia: Diagnosing and Treating Malignant Hyperthermia.

Overdose

Anesthesia medications are carefully calculated and administered based on a client’s individual characteristics and expected metabolism. However, complications can arise if a client’s metabolism and drug elimination are slower than anticipated. This is more likely to occur in older adults or those with preexisting liver or kidney problems. Anesthesia overdose can lead to adverse effects, ranging from minor discomfort to serious complications. Proper monitoring and precise dosage administration are essential to avoid such issues and ensure client safety.[24]

Unrecognized Hypoventilation

One of the critical aspects of anesthesia care is maintaining adequate ventilation to ensure proper gas exchange. Unrecognized hypoventilation, where the client fails to effectively exchange oxygen and carbon dioxide (CO2), can lead to serious consequences, including cardiac arrest, permanent brain damage, or death. Continuous monitoring of end-tidal carbon dioxide (ETCO2) levels is crucial for detecting changes in CO2 levels in the expired air. This monitoring helps identify hypoventilation early and allows immediate intervention to correct the issue and prevent complications.[25],[26]

Complications of Intubation

Intubation, the process of placing a breathing tube into the client’s airway, is a common practice during general anesthesia. See Figure 2.2[27] for an illustration of intubation with an endotracheal tube. However, intubation can cause potential complications. Clients may experience minor issues such as a sore throat after intubation. In more severe cases, complications can include broken or injured teeth and dental caps, swollen lips, and vocal cord trauma. Intubation can be challenging, especially in clients with anatomical variations or underlying diseases. Improper neck extension during intubation can also lead to injury. Anesthesia providers must exercise caution and expertise during this procedure to minimize the risk of complications and ensure client comfort and safety.[28],[29]

Local Anesthesia

Local anesthesia is a valuable technique used to disrupt sensory impulse transmission and reduce sensory perception in a limited area of the body. It is administered topically or through local infiltration, making it an effective option for minor surgical procedures or for providing pain relief during medical interventions. Unlike general anesthesia, local anesthesia allows the client to remain conscious and responsive throughout the procedure, enhancing client cooperation and communication. This form of anesthesia is commonly used in outpatient settings, as it allows for a faster recovery and reduced risk of complications compared to more invasive approaches.[30]

Topical application of local anesthesia involves applying anesthetic agents directly to the skin or mucous membranes. This method numbs the superficial tissues and is particularly useful for minor procedures like suturing small wounds or inserting intravenous (IV) lines. For example, topical or intradermal lidocaine may be applied to numb the area before starting an IV, reducing the pain and discomfort associated with the needle insertion. Additionally, local infiltration involves injecting the anesthetic agent directly into the tissues surrounding the targeted area. This method provides deeper anesthesia and is commonly used for procedures like dental work, minor joint surgeries, and skin biopsies.[31] See Figure 2.3[32] for an image of local anesthesia used during a dental procedure.

Although local anesthesia is generally considered safe and is tolerated well by most clients, there are some risks. These include the potential for allergic reactions, ranging from mild skin irritation to anaphylaxis. Systemic toxicity may be an additional risk. Potential complications of local anesthesia are described in Table 2.2d.

Table 2.2d. Potential Complications of Local Anesthesia[33],[34]

| Complication | Description |

|---|---|

| Allergic Reactions | Some individuals may be allergic to the local anesthetic agent, leading to mild to severe reactions, including anaphylaxis. |

| Systemic Toxicity | Inadvertent absorption of the anesthetic into the bloodstream can cause systemic toxicity with symptoms like dizziness, seizures, and cardiac disturbances. |

| Nerve Injury | Local anesthetic injection can occasionally cause nerve injury, resulting in temporary or rare permanent changes in sensation or function in the affected area. |

| Hematoma Formation | Injections into areas with blood vessels may lead to hematoma formation, particularly in regions with abundant blood supply. |

| Infection | There is a small risk of infection at the injection site, although proper sterile technique can reduce this risk. |

Regional Anesthesia

Regional anesthesia is a type of local anesthesia that involves blocking multiple peripheral nerves in a specific body region. It provides excellent pain relief and anesthesia for a targeted area without causing unconsciousness, making it particularly useful when a client cannot or prefers not to undergo general anesthesia. Regional anesthesia is often employed in various surgical and medical procedures, ranging from minor surgeries like dental or plastic surgery to more extensive interventions like joint replacements or chronic pain management.[35]

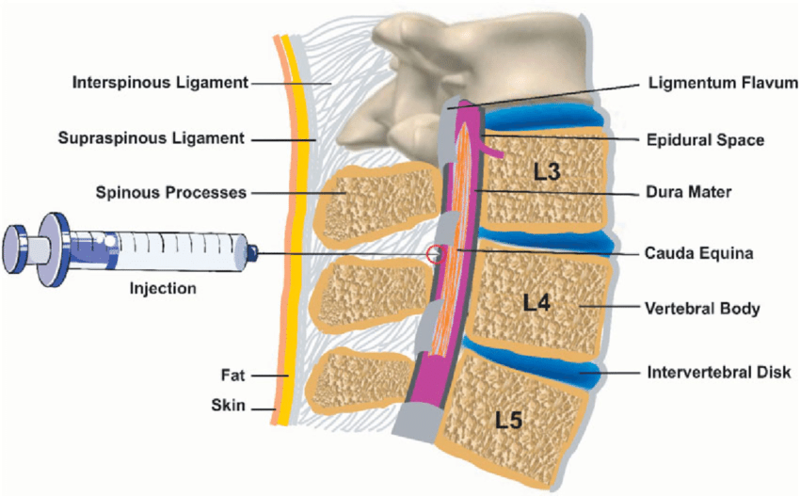

There are several types of regional blocks. Field blocks involve a series of local anesthetic injections around the operative field. It is commonly used in dental and plastic surgery to provide anesthesia to a specific area. Nerve blocks involve the injection of a local anesthetic into or around a single nerve or a group of nerves in the involved area. This type of block is commonly used in limb surgeries and chronic pain management. Spinal blocks require injecting an anesthetic agent into the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) in the subarachnoid space, providing anesthesia for lower abdominal surgeries, pelvic procedures, and hip and knee surgeries. Epidural blocks involve injecting the anesthetic agent into the epidural space, offering anesthesia for vaginal, perineal, hip, and lower extremity surgeries.[36] See Figure 2.4[37] for an illustration of administration of an epidural block.

The complications of regional anesthesia can vary depending on the specific type of block used, the client’s individual factors, and the skill and experience of the anesthesia provider. Potential complications of regional anesthesia are described in Table 2.2f.

Table 2.2f. Potential Complications of Regional Anesthesia[38], [39]

| Complication | Description |

|---|---|

| Spinal Headache | A headache that develops due to leakage of cerebral spinal fluid (CSF) after injection of anesthesia into the subarachnoid space. Usually resolves on its own, but in some cases may require an epidural blood patch to stop the leak. |

| Nerve Injury | Rare but serious, nerve injury can occur during regional anesthesia due to trauma to nerves or the effects of the anesthetic agent on nerve function. |

| Infection | Any breach of the skin during regional anesthesia can lead to infection at the injection site, although adherence to aseptic techniques can minimize the risk. |

| Systemic Toxicity | Absorption of local anesthetic into the bloodstream during regional blocks can cause systemic toxicity with symptoms like dizziness, seizures, and cardiac issues. |

| Bleeding and Hematoma | Needle insertion may cause bleeding or hematoma formation, leading to localized swelling and pressure that may affect nerve function or wound healing. |

| Respiratory Compromise | In certain regional blocks, the anesthetic agent can affect respiratory muscle function, leading to breathing difficulties, especially in clients with respiratory issues. |

| Allergic Reactions | While rare, some clients may experience allergic reactions to the local anesthetic agent, ranging from mild rashes to severe anaphylaxis, requiring immediate attention. |

Conscious Sedation

Conscious sedation, also known as “moderate sedation,” is a form of anesthesia administered through intravenous (IV) delivery of sedative, hypnotic, and opioid drugs to reduce the client’s level of consciousness. During conscious sedation, the client remains conscious and responsive but experiences a state of deep relaxation and drowsiness. This form of anesthesia is commonly used for minor surgical procedures, diagnostic tests, or other medical interventions where the client requires pain management and anxiety reduction without the need for complete unconsciousness.[40]

The administration of conscious sedation is typically performed by a credentialed registered nurse (RN) with specialized training in airway management, IV drug delivery, and Advanced Cardiac Life Support (ACLS). The most commonly used drugs for conscious sedation include etomidate, diazepam, midazolam, meperidine, fentanyl, alfentanil, and morphine sulfate. The goal of conscious sedation is to achieve a state where the client is sleepy but can be easily aroused and respond to verbal commands.[41]

Continuous monitoring is essential during conscious sedation to ensure the client’s safety and well-being. The RN closely monitors the client’s airway, level of consciousness, oxygen saturation, carbon dioxide (CO2) levels, electrocardiogram (ECG), and vital signs, typically at 15- to 30-minute intervals post-procedure until the client returns to their baseline state. The action of the sedative and opioid drugs used for conscious sedation is relatively short, allowing for a rapid return to daily activities (ADLs) once the procedure is completed. To prevent aspiration, clients are advised not to consume any oral intake until at least 30 minutes after the conscious sedation procedure. Conscious sedation provides effective pain management and relaxation while minimizing the risks associated with general anesthesia, making it a safe and widely utilized option for appropriate medical procedures.[42],[43]

Conscious sedation is generally safe when administered by trained and experienced health care professionals. Potential complications of conscious sedation are described in Table 2.2f.

Table 2.2f. Potential Complications of Conscious Sedation[44],[45]

| Complication | Description |

|---|---|

| Respiratory Depression | Slow and shallow breathing can occur during conscious sedation, particularly with the use of opioids or sedative drugs, potentially leading to decreased blood oxygen levels and hypoxia. |

| Airway Obstruction | Relaxed throat muscles or airway positioning may cause airway obstruction in clients under conscious sedation. Maintaining a clear airway is crucial to prevent respiratory distress or choking. |

| Hypotension and Bradycardia | Certain medications used in conscious sedation can cause a drop in blood pressure (hypotension) and a decrease in heart rate (bradycardia), which can be problematic, especially for clients with preexisting cardiovascular conditions. |

| Allergic Reactions | Allergic responses to medications used in conscious sedation may range from mild skin rashes to severe anaphylaxis, necessitating immediate medical intervention. |

| Oversedation or Under Sedation | Achieving the right level of sedation can be challenging, leading to either oversedation (unresponsiveness or unconsciousness) or under sedation (anxiety and discomfort) in some clients. |

| Nausea and Vomiting | Certain medications used during conscious sedation, especially opioids, can cause nausea and vomiting in some clients. |

| Delayed Recovery | While conscious sedation allows for a rapid return to daily activities, some clients may experience delayed recovery, feeling groggy or tired after the procedure. |

Monitored Anesthesia

Monitored anesthesia care (MAC) is a type of anesthesia used to provide a safe and comfortable experience for clients undergoing certain medical procedures or surgeries. Unlike general anesthesia, which renders the client completely unconscious, MAC anesthesia involves the administration of intravenous (IV) sedative and pain-relieving medications to achieve a state of “moderate sedation.” During MAC anesthesia, the client remains conscious and responsive, but in a deeply relaxed and drowsy state. The anesthesia provider carefully monitors the client’s vital signs, level of consciousness, and response to the medications throughout the procedure.[46],[47]

MAC anesthesia is commonly used for minor surgical procedures, endoscopic examinations, or diagnostic tests that do not require complete unconsciousness. It is particularly beneficial for clients who may not tolerate or prefer not to undergo general anesthesia. By avoiding the risks associated with deeper levels of anesthesia, such as respiratory depression or airway complications, MAC anesthesia provides a safer alternative while still providing adequate pain relief and client comfort.[48],[49]

The anesthesia provider, typically an anesthesiologist or certified registered nurse anesthetist (CRNA), administers a combination of sedatives and analgesics tailored to each client’s individual needs. These medications produce a state of conscious sedation, allowing clients to follow verbal commands and respond to stimuli while minimizing anxiety and discomfort. The level of sedation can be adjusted throughout the procedure to maintain the desired level of comfort and cooperation. After the procedure, clients generally recover quickly and can often resume their daily activities shortly thereafter. Overall, MAC anesthesia offers a balanced approach to anesthesia, combining client safety with optimal pain management and reduced risk, making it a valuable choice for appropriate medical interventions.[50] As with any medical procedure, MAC anesthesia comes with potential risks, and these complications should be diligently managed by skilled health care professionals. Potential complications of MAC anesthesia are summarized in Table 2.2g.

Table 2.2g. Potential Complications of MAC[51],[52]

| Complication | Description |

|---|---|

| Respiratory Depression | Sedative medications used in MAC anesthesia can cause respiratory depression, resulting in slow or shallow breathing and reduced blood oxygen levels, potentially leading to hypoxia. |

| Airway Obstruction | Clients under MAC anesthesia may experience airway obstruction due to relaxed throat muscles or positional changes. Maintaining a clear airway is essential to prevent respiratory distress and choking. |

| Hypotension and Bradycardia | MAC anesthesia medications can lead to changes in blood pressure and heart rate, causing hypotension (low blood pressure) and bradycardia (slow heart rate), particularly in clients with preexisting cardiovascular conditions. |

| Delayed Recovery | While MAC anesthesia offers a faster recovery compared to general anesthesia, some clients may still experience delayed recovery, feeling groggy or tired after the procedure. |

| Allergic Reactions | Some clients may have allergic reactions to the medications used in MAC anesthesia, ranging from mild skin rashes to severe anaphylaxis, requiring immediate medical attention. |

| Nausea and Vomiting | Certain medications used during MAC anesthesia, especially opioids, may cause nausea and vomiting in some clients. |

| Oversedation or Under Sedation | Achieving the appropriate level of sedation can be challenging, leading to either oversedation (unresponsiveness) or under sedation (inadequate relaxation), which require careful monitoring and adjustment during the procedure. |

Surgical Safety

Surgical safety checklists are used during surgery to emphasize that client safety is the primary concern for all personnel involved in surgical care. It serves as a reminder that the well-being and safety of the client should always take precedence throughout the entire perioperative period. The World Health Organization (WHO) Surgical Safety Checklist serves as a standardized framework that helps health care teams ensure critical safety measures are consistently implemented before, during, and after surgery. The checklist emphasizes the importance of communication, teamwork, and adherence to safety protocols.[53]

Examples of items on the surgical safety checklist include the following[54]:

- Confirm client identity: Client identity is verified by cross-checking their name, date of birth, and other identifying information. This step helps prevent wrong-client procedures.

- Verify surgical site is marked: The correct surgical site is identified and marked before the procedure. Site marking is particularly important for surgeries involving multiple anatomical structures or when there is a risk of confusion. Read more information about site marking from The Joint Commission using the information in the box below.

- Ensure documentation is reviewed: Necessary imaging and documentation (e.g., X-rays, consent forms) are available and reviewed.

- Monitor pulse oximeter: A pulse oximeter is a device used to monitor oxygen levels in the blood. It is used for continuous monitoring of the client’s oxygenation status during surgery.

- Verify anesthesia safety: Client allergies and any special requirements related to anesthesia are verified, as well as confirmation of the availability and proper functioning of necessary anesthesia equipment and medications. The client’s airway management plan is reviewed.

- Administer prophylactic antibiotics: Appropriate administration of prophylactic antibiotics within the recommended time frame is verified before incision takes place.

- Count instruments, sponges, and needles: Accurate counting of surgical instruments, sponges, and needles is verified before and after the procedure to prevent retention of foreign objects.

- Team briefing: A preprocedural briefing is conducted with the surgical team to review critical information, discuss potential risks or concerns, and ensure everyone is on the same page.[55]

Read more about the universal protocol to prevent wrong site, wrong procedure, and wrong person surgery in a PDF from The Joint Commission: Universal Protocol Poster.

Research has shown the WHO Surgical Safety Checklist improves client outcomes, reduces complications, and enhances teamwork and communication in the operating room.[56] By following the checklist, health care teams can minimize errors, ensure compliance with essential safety measures, and ultimately enhance the overall quality and safety of surgical care.

In addition to the WHO Surgical Safety Checklist, adverse events like wrong-site surgery, falls, pressure ulcers, and other adverse events are reportable to regulatory bodies like the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS).[57] This increased accountability places responsibility on health care facilities to implement measures to promote client safety and prevent adverse events. The WHO Surgical Safety Checklist aligns with this focus on accountability by providing a structured approach to enhance client safety and reduce the occurrence of preventable adverse events.[58]

View the WHO Surgical Safety Checklist: Surgical Safety Checklist PDF.

Surgical Hand Scrub

Nurses and other members of the surgical team are responsible for performing a thorough surgical hand scrub using an antiseptic solution. This process is crucial to eliminate microorganisms from the hands and forearms before donning sterile gloves and gowns to maintain aseptic conditions during the surgery and prevent infection.[59] Review information about performing a surgical scrub in the following box.

Surgical Scrub[60]

A surgical scrub does not make the skin sterile, but it significantly reduces the risk of infection by eliminating a large number of organisms on the skin.

Key steps of a surgical scrub include the following:

Remove Jewelry: Before beginning the scrub, any rings, watches, bracelets, or other jewelry on the hands and forearms are removed. These items can harbor microorganisms and interfere with proper handwashing.

Trim Nails and Remove Artificial Nails: Short and natural nails are preferred. Long or artificial nails can harbor bacteria and reduce the effectiveness of handwashing.

Prerinse with Water: The hands and forearms are prerinsed with water to remove dirt and debris from the skin surface.

Apply Antiseptic Solution: An antiseptic solution, usually chlorhexidine or povidone-iodine, is applied to the hands and forearms. The scrub begins by focusing on the nails and cuticles and then moves up the arms.

Scrub Thoroughly: The hands and forearms are scrubbed thoroughly, paying attention to all areas, including the spaces between fingers, the back of hands, and up to two inches above the elbows. The scrub should last for the recommended duration, typically around 2 to 5 minutes, depending on the facility’s policy.

Allow Water to Run Off Arms: While scrubbing, the hands and arms are held in a way that allows the water to flow from the fingertips downward, preventing contamination from higher, less clean areas.

Assist With Gowning and Gloving: After completing the scrub, the surgical team member is assisted in donning a sterile gown and sterile gloves by another team member who has not performed the scrub. This ensures that the sterile field is not compromised during the process. It is vital for team members to be mindful of the boundaries of the sterile gown and the sterile field throughout the surgical procedure. The sleeves of the gown are considered sterile up to two inches above the elbows, the front of the gown is considered sterile from chest level down, and the back of the gown is considered nonsterile.

Perform Routine Hand Cultures: In some settings, health care workers may undergo routine hand cultures to detect potential sources of infections. This helps monitor the effectiveness of hand hygiene practices and identify areas for improvement.

View a supplementary YouTube video[61] from Johns Hopkins Medicine on performing a surgical scrub: Anatomical Surgical Hand Scrub.

Informed Consent

Informed consent is a key concept for maintaining autonomy for surgical clients. Informed consent ensures an active, shared decision-making process between the health care provider and the recipient of care, empowering clients to participate in decisions about their treatment and surgical procedures. Adequate disclosure is a key aspect of informed consent, whereby clients are provided with comprehensive information about the nature of the surgery, the individuals involved in the procedure (including students), available treatment options, and the associated risks of each option. Additionally, clients should be informed about the potential risks associated with anesthesia.[62]

To ensure the validity of consent, three conditions must be met. First, there should be adequate disclosure by the surgeon/physician of the diagnosis, risks, outcomes, and nature and purpose of the treatment/surgery, as well as the prognosis if the treatment is not instituted. Second, clients must demonstrate understanding and comprehension of the information provided before receiving any sedating preoperative medications. Lastly, consent must be given voluntarily, without any form of persuasion or coercion.[63]

While the responsibility of obtaining signed consent lies with the surgeon, nurses play a crucial role in the process by assisting in obtaining and witnessing the client’s signature as valid consent according to these conditions. Nurses can also contribute by clarifying facts presented by the physician and dispelling any myths or misconceptions that the client or family may have about the surgery. If a client remains unclear about the surgery after clarification by the nurse, the nurse will refer the client back to the surgeon for further education.

It is important to note that in medical emergencies where immediate intervention is necessary to safeguard the client’s health, the need to obtain consent may be overridden. However, consent should be obtained as soon as possible after the emergency situation has been addressed.[64]

Keep in mind that once a client has received any type of sedation, they cannot sign informed consent. For this reason, multiple consents may be performed prior to undergoing a procedure, such as signing a consent for a possible open-heart surgery if undergoing a catheterization in the Cardiac Cath Lab.

Clients have the right to withdraw their consent before undergoing surgery, and health care providers must respect their decision in such cases. Consent should be an ongoing process, allowing clients to make informed choices about their health care.[65],[66]

Life Span Considerations

Older Adult Considerations

- Older adults have increased risk of surgical complications due to factors such as delayed immune system response, delayed wound healing, delayed renal excretion, decreased muscle mass, increased risk of dehydration, and decreased physiological reserve.

- The risk for hypoventilation is increased following surgery. Nursing considerations include end-tidal CO2 monitoring to identify hypoventilation.

- Older clients have a decreased immune system and potential for delayed wound healing.

- Age-related changes to the kidneys and liver may delay the elimination of anesthesia or analgesics as clients age.

- Many older adults have chronic health problems impacting their cardiovascular, renal, hepatic, and respiratory systems, making them more vulnerable to fluid and electrolyte imbalances.

- Nursing considerations may include renal or hepatic doses of preoperative and postoperative medications due to underlying medical conditions.

- Unfamiliar surroundings, decreased hearing and vision, forgetfulness, and anxiety about surgery may impact an elderly client’s ability to remember and understand surgical instructions. Advocating for another family member to be present is an appropriate nursing recommendation.

- Fragile skin and less subcutaneous tissue make skin breakdown a potential complication. Nursing considerations include integumentary assessments and musculoskeletal position changes.[67]

Pediatric Considerations

- Age-appropriate language, family dynamics, and assessment of a client’s developmental stage are unique pediatric nursing considerations.

- Preoperative anxiety and fear of parental separation require nursing assessment and planning for potential preanesthetic medications to reduce symptomatology.

- A comprehensive care plan emphasizing patience, empathy, knowledge, skill, and common sense practiced by the multidisciplinary team acknowledges pediatric needs.

- Use of an induction room (safe space) where clients remain clothed and aren’t subject to procedures or skills (IVs, laboratory draws, etc.) is a nonpharmacologic anxiety-reducing strategy.

- Alternative methods to verify identity with peers or family members may be necessary due to lack of speech.[68]

- Vera, M. (2024) 12 surgery (perioperative client) nursing care plans. Nurselabs. https://nurseslabs.com/surgery-perioperative-client-nursing-care-plans/ ↵

- American College of Surgeons. (n.d.). What are the surgical specialties? https://www.facs.org/for-medical-professionals/education/online-guide-to-choosing-a-surgical-residency/guide-to-choosing-a-surgical-residency-for-medical-students/faqs/specialties/ ↵

- American College of Surgeons. (n.d.). What are the surgical specialties? https://www.facs.org/for-medical-professionals/education/online-guide-to-choosing-a-surgical-residency/guide-to-choosing-a-surgical-residency-for-medical-students/faqs/specialties/ ↵

- Johns Hopkins Medicine. (n.d.). Surgical team. https://www.hopkinsmedicine.org/health/treatment-tests-and-therapies/the-surgical-team ↵

- American Association of Moderate Sedation Nurses. (n.d.). Registered nurse (CSRM) scope of practice: Certification sedation registered nurse (CSRN) scope of practice. https://aamsn.org/resources/pdfs/sedation-related-pdfs/registered-nurse-csrn-scope-of-practice ↵

- Bureau of Labor Statistics, U.S. Department of Labor, Occupational Outlook Handbook. (2023). Surgical Assistants and Technologists. https://www.bls.gov/ooh/healthcare/surgical-technologists.htm ↵

- Bureau of Labor Statistics, U.S. Department of Labor, Occupational Outlook Handbook. (2023). Surgical Assistants and Technologists. https://www.bls.gov/ooh/healthcare/surgical-technologists.htm ↵

- Mayo Clinic College of Medicine and Science. (n.d.). Perioperative nurse. https://college.mayo.edu/academics/explore-health-care-careers/careers-a-z/perioperative-nurse/ ↵

- Mayo Clinic College of Medicine and Science. (n.d.). Perioperative nurse. https://college.mayo.edu/academics/explore-health-care-careers/careers-a-z/perioperative-nurse/ ↵

- Falk, S. A., & Fleisher, L. A. (2023). Overview of anesthesia. UpToDate. https://www.wolterskluwer.com/en/solutions/uptodate ↵

- Falk, S. A., & Fleisher, L. A. (2023). Overview of anesthesia. UpToDate. https://www.wolterskluwer.com/en/solutions/uptodate ↵

- Falk, S. A., & Fleisher, L. A. (2023). Overview of anesthesia. UpToDate. https://www.wolterskluwer.com/en/solutions/uptodate ↵

- Falk, S. A., & Fleisher, L. A. (2023). Overview of anesthesia. UpToDate. https://www.wolterskluwer.com/en/solutions/uptodate ↵

- Falk, S. A., & Fleisher, L. A. (2023). Overview of anesthesia. UpToDate. https://www.wolterskluwer.com/en/solutions/uptodate ↵

- Falk, S. A., & Fleisher, L. A. (2023). Overview of anesthesia. UpToDate. https://www.wolterskluwer.com/en/solutions/uptodate ↵

- Falk, S. A., & Fleisher, L. A. (2023). Overview of anesthesia. UpToDate. https://www.wolterskluwer.com/en/solutions/uptodate ↵

- Falk, S. A., & Fleisher, L. A. (2023). Overview of anesthesia. UpToDate. https://www.wolterskluwer.com/en/solutions/uptodate ↵

- Falk, S. A., & Fleisher, L. A. (2023). Overview of anesthesia. UpToDate. https://www.wolterskluwer.com/en/solutions/uptodate ↵

- Falk, S. A., & Fleisher, L. A. (2023). Overview of anesthesia. UpToDate. https://www.wolterskluwer.com/en/solutions/uptodate ↵

- “Pacific-partnership-2012_594038.jpg” by U.S. Navy photo by Mass Communication Specialist 3rd Class Michael Feddersen is licensed in the Public Domain." The appearance of U.S. Department of Defense (DoD) visual information does not imply or constitute DoD endorsement." ↵

- Falk, S. A., & Fleisher, L. A. (2023). Overview of anesthesia. UpToDate. https://www.wolterskluwer.com/en/solutions/uptodate ↵

- Rosenbaum, H. K., & Rosenberg, H. (2022). Malignant hyperthermia: Diagnosis and management of acute crisis. UpToDate. https://www.wolterskluwer.com/en/solutions/uptodate ↵

- Beaumont Health. (2017, June 2). Diagnosing and treating malignant hyperthermia [Video]. YouTube. All rights reserved. https://youtu.be/cXa5ej-CszQ?si=M-Tog1hYPowHEt6P ↵

- Falk, S. A., & Fleisher, L. A. (2023). Overview of anesthesia. UpToDate. https://www.wolterskluwer.com/en/solutions/uptodate ↵

- Falk, S. A., & Fleisher, L. A. (2023). Overview of anesthesia. UpToDate. https://www.wolterskluwer.com/en/solutions/uptodate ↵

- Steadman, J., Catalani, B., Sharp, C., & Cooper, L. (2017). Life-threatening perioperative anesthetic complications: Major issues surrounding perioperative morbidity and mortality. Trauma Surgery & Acute Care Open, 2(1), e000113. https://doi.org/10.1136/tsaco-2017-000113 ↵

- “Endotracheal_Tube.png” by BruceBlaus is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0 ↵

- Falk, S. A., & Fleisher, L. A. (2023). Overview of anesthesia. UpToDate. https://www.wolterskluwer.com/en/solutions/uptodate ↵

- Steadman, J., Catalani, B., Sharp, C., & Cooper, L. (2017). Life-threatening perioperative anesthetic complications: Major issues surrounding perioperative morbidity and mortality. Trauma Surgery & Acute Care Open, 2(1), e000113. https://doi.org/10.1136/tsaco-2017-000113 ↵

- Falk, S. A., & Fleisher, L. A. (2023). Overview of anesthesia. UpToDate. https://www.wolterskluwer.com/en/solutions/uptodate ↵

- Falk, S. A., & Fleisher, L. A. (2023). Overview of anesthesia. UpToDate. https://www.wolterskluwer.com/en/solutions/uptodate ↵

- “DentalLocalAnesthesia11-26-05.jpg” by Dozenist is licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0 ↵

- Falk, S. A., & Fleisher, L. A. (2023). Overview of anesthesia. UpToDate. https://www.wolterskluwer.com/en/solutions/uptodate ↵

- American Society of Anesthesiologists. (n.d.). Local anesthesia. https://www.asahq.org/madeforthismoment/anesthesia-101/types-of-anesthesia/local-anesthesia/ ↵

- Falk, S. A., & Fleisher, L. A. (2023). Overview of anesthesia. UpToDate. https://www.wolterskluwer.com/en/solutions/uptodate ↵

- Falk, S. A., & Fleisher, L. A. (2023). Overview of anesthesia. UpToDate. https://www.wolterskluwer.com/en/solutions/uptodate ↵

- “Epidural-anesthesia.png” by Leila Kafshdooz, Houman Kahroba, Tayebeh Kafshdooz, Roghayeh Sheervalilou & Hojjat Pourfathi is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- Falk, S. A., & Fleisher, L. A. (2023). Overview of anesthesia. UpToDate. https://www.wolterskluwer.com/en/solutions/uptodate ↵

- Jeng, C. L., & Rosenblatt, M. A. (2023). Overview of peripheral nerve blocks. UpToDate. https://www.wolterskluwer.com/en/solutions/uptodate ↵

- Falk, S. A., & Fleisher, L. A. (2023). Overview of anesthesia. UpToDate. https://www.wolterskluwer.com/en/solutions/uptodate ↵

- Falk, S. A., & Fleisher, L. A. (2023). Overview of anesthesia. UpToDate. https://www.wolterskluwer.com/en/solutions/uptodate ↵

- Falk, S. A., & Fleisher, L. A. (2023). Overview of anesthesia. UpToDate. https://www.wolterskluwer.com/en/solutions/uptodate ↵

- Crego, N. (2016). Procedural sedation practice: A review of current nursing standards. Journal of Nursing Regulations, 6(1), 50-56. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC8923528/ ↵

- Falk, S. A., & Fleisher, L. A. (2023). Overview of anesthesia. UpToDate. https://www.wolterskluwer.com/en/solutions/uptodate ↵

- Crego, N. (2016). Procedural sedation practice: A review of current nursing standards. Journal of Nursing Regulations, 6(1), 50-56. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC8923528/ ↵

- Falk, S. A., & Fleisher, L. A. (2023). Overview of anesthesia. UpToDate. https://www.wolterskluwer.com/en/solutions/uptodate ↵

- Rosero, E. B. (2023). Monitored anesthesia care in adults. UpToDate. https://www.wolterskluwer.com/en/solutions/uptodate ↵

- Falk, S. A., & Fleisher, L. A. (2023). Overview of anesthesia. UpToDate. https://www.wolterskluwer.com/en/solutions/uptodate ↵

- Rosero, E. B. (2023). Monitored anesthesia care in adults. UpToDate. https://www.wolterskluwer.com/en/solutions/uptodate ↵

- Rosero, E. B. (2023). Monitored anesthesia care in adults. UpToDate. https://www.wolterskluwer.com/en/solutions/uptodate ↵

- Falk, S. A., & Fleisher, L. A. (2023). Overview of anesthesia. UpToDate. https://www.wolterskluwer.com/en/solutions/uptodate ↵

- Rosero, E. B. (2023). Monitored anesthesia care in adults. UpToDate. https://www.wolterskluwer.com/en/solutions/uptodate ↵

- World Health Organization. (2023). WHO surgical safety checklist. https://www.who.int/teams/integrated-health-services/patient-safety/research/safe-surgery/tool-and-resources ↵

- World Health Organization. (2023). WHO surgical safety checklist. https://www.who.int/teams/integrated-health-services/patient-safety/research/safe-surgery/tool-and-resources ↵

- World Health Organization. (2023). WHO surgical safety checklist. https://www.who.int/teams/integrated-health-services/patient-safety/research/safe-surgery/tool-and-resources ↵

- World Health Organization. (2023). WHO surgical safety checklist. https://www.who.int/teams/integrated-health-services/patient-safety/research/safe-surgery/tool-and-resources ↵

- Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. (2008). Surgery on the wrong body part. https://www.cms.gov/medicare-coverage-database/view/ncacal-decision-memo.aspx?proposed=Y&ncaid=222 ↵

- World Health Organization. (2023). WHO surgical safety checklist. https://www.who.int/teams/integrated-health-services/patient-safety/research/safe-surgery/tool-and-resources ↵

- Benze, C., Spruce, L., & Graph, L. (2021). Perioperative nursing: Scope and standards of practice. AORN. https://www.aorn.org/docs/default-source/guidelines-resources/periop-nursing-scope-standards-of-practice.pdf?sfvrsn=c532cdee_1 ↵

- Anderson, D. J., & Sexton, D. J. (2022). Overview of control measures for prevention of surgical site infection in adults. UpToDate. https://www.wolterskluwer.com/en/solutions/uptodate ↵

- John Hopkins Medicine. (2018, December 14). Anatomical surgical hand scrub [Video]. YouTube. All rights reserved. https://youtu.be/WpZqLbWL0c0?si=asgQlMdlnlxPb7LE ↵

- Ryan, M., & Sinha, M. S. (2023). Informed procedural consent. UpToDate. https://www.wolterskluwer.com/en/solutions/uptodate ↵

- Ryan, M., & Sinha, M. S. (2023). Informed procedural consent. UpToDate. https://www.wolterskluwer.com/en/solutions/uptodate ↵

- American Medical Association. (n.d.). AMA Code of Medical Ethics: 2.1.1 informed consent. https://code-medical-ethics.ama-assn.org/sites/default/files/2022-08/2.1.1.pdf ↵

- Ryan, M., & Sinha, M. S. (2023). Informed procedural consent. UpToDate. https://www.wolterskluwer.com/en/solutions/uptodate ↵

- American Medical Association. (n.d.). AMA Code of Medical Ethics: 2.1.1 informed consent. https://code-medical-ethics.ama-assn.org/sites/default/files/2022-08/2.1.1.pdf ↵

- Baquero, G.A. & Rich, M.W. (2015). Perioperative care in older adults. Journal of Geriatric Cardiology, 12(5), 465-9. https://doi.org/10.11909/j.issn.1671-5411.2015.05.018 ↵

- Baquero, G.A. & Rich, M.W. (2015). Perioperative care in older adults. Journal of Geriatric Cardiology, 12(5), 465-9. https://doi.org/10.11909/j.issn.1671-5411.2015.05.018 ↵

Performed to obtain a definitive diagnosis or to assess the extent of a disease or condition.

Performed to remove or treat the cause of a disease, providing a cure or permanent resolution.

Aimed at restoring function and improving the quality of life, often involving replacing a body part.

Performed to alleviate symptoms, reduce pain, or improve the client's comfort without curing the disease.

Performed primarily to enhance or alter a person's appearance.

Performed to visualize and inspect internal organs and structures to diagnose or assess health conditions.

Performed to replace a failed organ or tissue with a healthy organ or tissue from a donor.

Performed to treat conditions affecting the nervous system, brain, and spinal cord.

Performed to treat conditions related to the heart and/or blood vessels, often to improve blood flow.

Performed to treat conditions related to the musculoskeletal system, dealing with bones, joints, muscles, ligaments, and tendons.

Performed to treat conditions related to pregnancy, childbirth, and female reproductive organs.

Performed to treat conditions related to the urinary system and male reproductive organs.

The client is admitted to the hospital either the day before the surgery or on the same day of the procedure.

Includes procedures where the client goes to the surgical area on the day of the surgery and returns home the same day, commonly known as same-day surgery.

Surgeries are performed in health care facilities where clients receive medical care or procedures without requiring hospitalization.

Urgent or emergency surgeries that are necessary to address critical conditions or life-threatening situations immediately within the ER setting.

Reduces or temporarily eliminate sensory perception, commonly referred to as "negative sensation"

Induces a state of unconsciousness and loss of sensation throughout the entire body.

Used to numb a specific area of the body, typically near the surgical site.

Numbing a larger area of the body, such as an entire limb or a section of the body, by blocking the nerve signals in that region.

Also known as moderate sedation or twilight anesthesia, is a state where the client remains conscious but deeply relaxed and pain-free.

The administration of IV sedation and pain management for clients undergoing certain procedures.

An acute, inherited muscle disorder triggered by certain drugs used for general anesthesia, specifically inhaled anesthetic agents or the muscle relaxant succinylcholine.

A series of local anesthetic injections around the operative field.

The injection of a local anesthetic into or around a single nerve or a group of nerves in the involved area.

Injecting an anesthetic agent into the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) in the subarachnoid space, providing anesthesia for lower abdominal surgeries, pelvic procedures, and hip and knee surgeries.

Injecting the anesthetic agent into the epidural space, offering anesthesia for vaginal, perineal, hip, and lower extremity surgeries.

Serves as a standardized framework that helps health care teams ensure critical safety measures are consistently implemented before, during, and after surgery.

Ensures an active, shared decision-making process between the health care provider and the recipient of care, empowering clients to participate in decisions about their treatment and surgical procedures.