10.6 Fracture

A fracture occurs when there is a break or disruption in the integrity of a bone. Fractures can vary in severity, location, and the way in which the bone breaks.

Types of Fractures

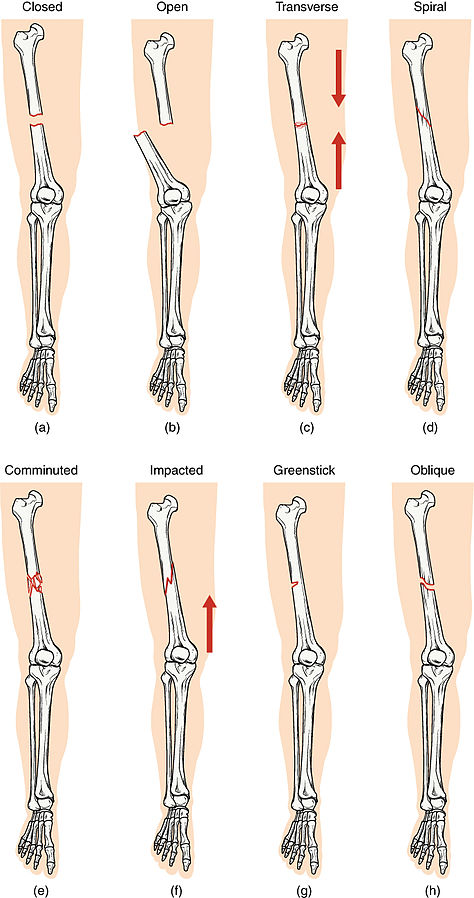

Different types of fractures include the following[1],[2],[3]:

- Closed or Simple: Bone is broken but does not protrude the skin

- Open or Compound: Bone is broken and pierces through the skin

- Transverse: Bone is broken straight across

- Spiral: Bone has twisted apart

- Comminuted: A bone is crushed into pieces

- Impacted: One fragment of the bone is driven into the other, usually as a result of compression

- Greenstick: Bone is partially broken; a common fracture in children that occurs rarely in adults

- Oblique: Bone is broken at an angle

- Stress: Small crack in a bone

- Complete Fracture: The bone breaks entirely into two or more separate pieces

- Incomplete Fracture: The bone cracks but doesn’t break into separate pieces (e.g., stress fracture or greenstick fracture)

- Compression Fracture: Typically occurs in vertebrae and involves the bone being crushed or collapsing; often seen in conditions like osteoporosis

- Pathologic Fracture: A fracture that occurs due to disease process

See Figure 10.26[4] for an illustration of different types of fractures.

Hip Fractures

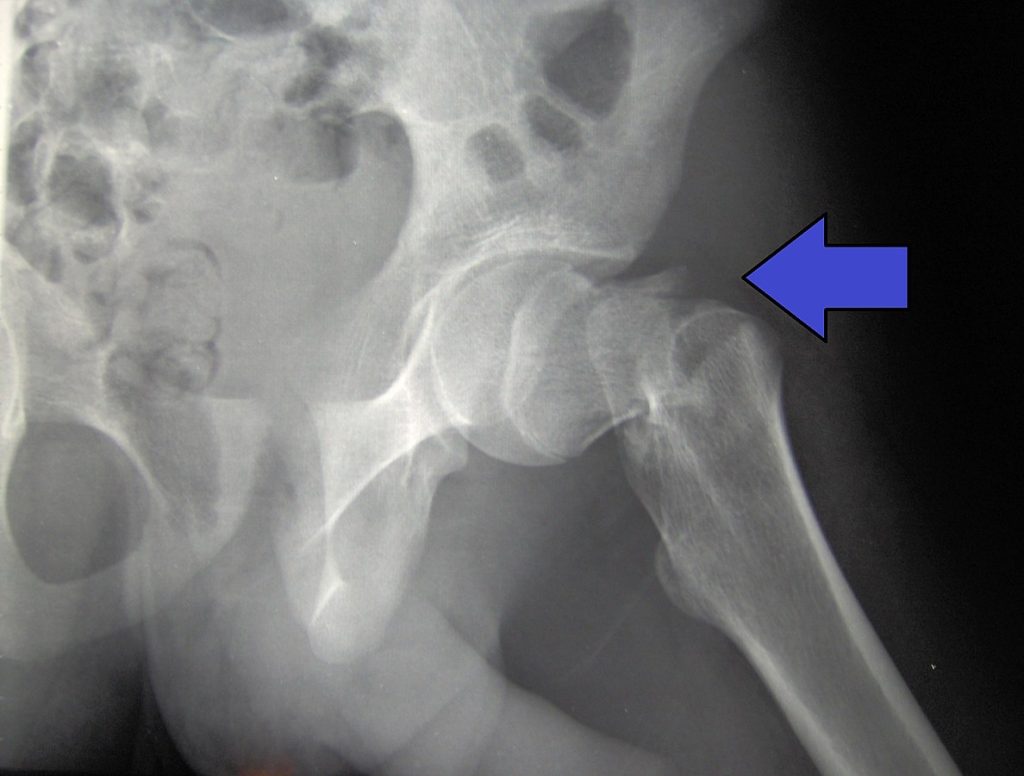

A hip fracture, commonly referred to as a “broken hip,” can be intracapsular or extracapsular. An intracapsular fracture occurs in the femoral neck, as illustrated in Figure 10.27.[5] Extracapsular fractures occur outside of the joint capsule and include the proximal one third of the femur.

Hip fractures are typically caused by a fall, especially in older adults with preexisting osteoporosis. Symptoms of a hip fracture include the following[6]:

- Pain

- An inability to lift, move, or rotate the affected leg

- An inability to stand or put weight on the affected leg

- Bruising and swelling around the hip

- The injured leg appears shorter than the other leg

- The injured leg is rotated outwards

Hip fractures typically require surgical repair within 48 hours of the injury. In approximately half of the cases, hip arthroplasty (i.e., hip replacement) is needed. In the remaining cases, the fracture is repaired during a surgery called open reduction internal fixation (ORIF). Read more information about ORIF in the “Medical Interventions” subsection.

Risk Factors for Fractures

There are numerous risk factors for fractures, including advancing age, trauma, and the presence of other medical conditions such as osteoporosis, metastatic cancer, or Cushing’s disease. Other risk factors include long-term use of corticosteroids, lack of physical activity or weight-bearing exercises, poor nutrition, and genetics. Women, especially after menopause, are at higher risk for fractures due to reduced bone density as a result of hormonal changes.

Stages of Bone Healing

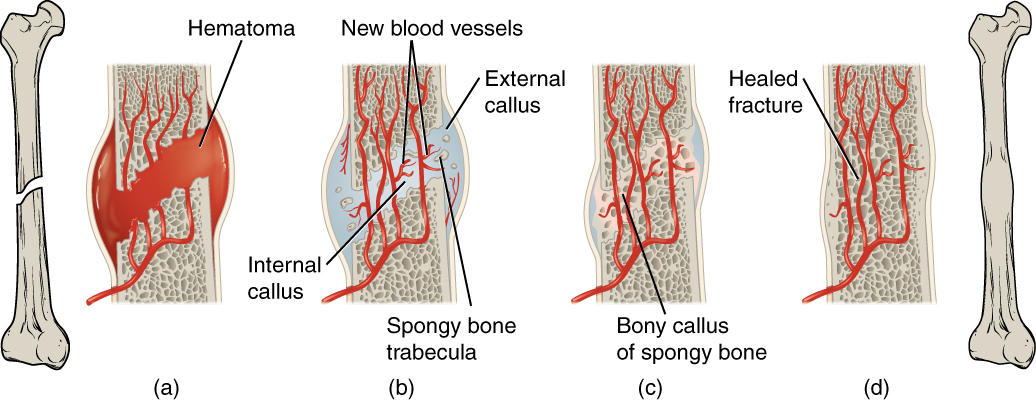

When a fracture occurs, the healing process immediately begins with the following stages of bone healing[7]:

- Hematoma Formation (within 48 to 72 hours after injury): Immediately after a bone fracture, blood vessels at the injury site rupture, leading to the formation of a blood clot or hematoma. The hematoma serves as a framework for subsequent healing processes.

- Hematoma to Granulation Tissue: Over the next few days, the hematoma transforms into granulation tissue, where new blood vessels and specialized cells invade the site to remove damaged tissue.

- Callus Formation: Within the first few weeks, the granulation tissue develops into a soft callus made of collagen and cartilage, stabilizing the fractured bone ends. This callus provides a temporary framework for bone healing.

- Osteoblastic Proliferation: Osteoblasts become active and start producing new bone tissue. These cells gradually replace the soft callus with a harder woven bone.

- Bone Remodeling: Over several weeks to months, the new woven bone is remodeled into stronger lamellar bone, resembling the original bone structure. Excess bone tissue is reabsorbed, and the bone undergoes restructuring to regain its strength and shape.

- Bone Healing Completion: Generally, bone healing is completed within about six weeks; however, in older individuals or cases with complications, it may take up to six months. The time required for complete healing varies based on factors such as age, overall health, the severity of the fracture, and the bone’s location.

See Figure 10.28[8] for an illustration of bone healing.

Assessment

The location and type of bone fracture can cause various assessment findings. Common manifestations of fractures by body system are summarized in Table 10.6.

Table 10.6. Manifestations of Fracture by Body System[9],[10],[11],[12]

| Body System | Assessment Findings |

|---|---|

| Musculoskeletal | Pain at the site of injury, swelling of soft tissue, deformity or misalignment, limited range of motion, tenderness upon palpation, and crepitus (grating sensation or sound) |

| Integumentary | Bruising or discoloration, open wounds or skin breaks, bleeding or hematoma, and warmth or redness over the affected area |

| Nervous | Numbness or tingling distal to the injury, loss of sensation, weakness in the affected limb, and loss of function (e.g., inability to move the affected area) |

| Cardiovascular | Pallor (pale skin) due to decreased blood flow, coldness in the affected area, decreased or absent pulses distal to the fracture, and delayed capillary refill |

| Respiratory | Rib fractures can cause shallow breathing, resulting in shortness of breath |

| Gastrointestinal | Nausea or vomiting due to pain or shock or abdominal tenderness with pelvic fractures |

| Psychosocial | Anxiety or distress, fear or worry about the injury, and impact on the ability to perform activities of daily living |

Potential Complications of Fractures

A fracture can result in severe complications if rapid swelling occurs in the surrounding tissues.

A significant complication associated with fracture is acute compartment syndrome (ACS), which is characterized by increased pressure within a muscle compartment, resulting in reduced blood flow to the tissues within that compartment. This heightened pressure impairs circulation, leading to tissue ischemia (lack of oxygen and nutrients) and subsequent tissue damage. Nurses monitor this complication and promptly notify the health care provider of concerns. Read additional information about ACS in the following box.

Acute Compartment Syndrome (ACS)

The pathophysiological changes in ACS are often described as an ischemia-edema cycle. Initially, an injury or trauma causes tissue damage, leading to inflammation and swelling (edema) within the affected compartment. Swelling and inflammation lead to increased pressure within the confined space of the muscle compartment. As pressure rises, it compresses blood vessels, reducing blood flow to the muscles and nerves. Decreased blood flow results in tissue ischemia, depriving the muscles and nerves of oxygen and nutrients. Without adequate blood supply, cells begin to die, and metabolic waste products accumulate in the tissue. Persistent elevation of compartment pressure further compromises circulation, exacerbating tissue damage and potentially leading to irreversible nerve and muscle injury.[13]

Warning signs of ACS are often referred to as the six P's[14]:

- Pain: Pain is typically the first sign of ACS. It is described as severe, unrelenting pain that is disproportionate to the injury and is unresponsive to opioid administration.

- Paresthesia: Abnormal or progressive loss of sensation.

- Poikilothermia: Cool skin.

- Pallor: Pale skin.

- Pulselessness: Decreased or absent pulses distal to the injury.

- Paralysis: Inability to move the extremity.

Early recognition and prompt intervention are crucial. Close monitoring of clients at risk, such as those with fractures, crush injuries, or extensive soft tissue trauma, can help prevent the progression of ACS.

ACS can be caused by a cast being too tight on an extremity and restricting blood flow, in which case the cast is removed. Otherwise, treatment of ACS often requires emergency fasciotomy, a surgical procedure that relieves pressure within the compartment by making incisions through the fascia (connective tissue surrounding the compartment) to release the built-up pressure. See Figure 10.29[15] for an image of a fasciotomy.[16]

Other potential complications of fractures include hypovolemic shock, fat embolism, deep vein thrombosis, and infection[17],[18],[19]:

- Hypovolemic Shock: Severe fractures, especially those involving significant bleeding, can cause hypovolemic shock, characterized by a rapid heart rate, low blood pressure, and altered consciousness. Immediate stabilization through intravenous fluids and blood transfusions restores blood volume and prevents further deterioration.

- Fat Embolism Syndrome: Fat embolism syndrome can arise from certain fractures, particularly long-bone fractures or bone with large amounts of marrow, such as the ribs, pelvis, and femur. In this condition, fat globules from the yellow bone marrow are released into the bloodstream, leading to potentially life-threatening emboli in the lungs, brain, and other organs. Symptoms include respiratory distress, altered mental status, petechial rash, and fever. Nurses assess for this complication and promptly request emergency assistance as indicated, which includes rapid administration of oxygen therapy, high Fowler’s positioning, and potential intubation and mechanical ventilation to maintain adequate oxygenation.

- Deep Vein Thrombosis (DVT): DVT is a significant risk following fractures, particularly during prolonged immobility. DVT refers to the formation of blood clots in deep veins, commonly in the legs, that can move in the bloodstream and become pulmonary emboli. Symptoms of DVT include unilateral swelling, pain, warmth, and redness in the affected limb. Preventive measures for DVT after fracture repair include early mobilization, anticoagulant therapy, and compression stockings. Read additional information about DVTs in the “Deep Vein Thrombosis” section of the “Cardiovascular Alterations” chapter.

- Infection: Local or systemic infections can occur from open fractures or surgical interventions when bacteria contaminate the wounds. Symptoms of infection include increased pain, redness, swelling, fever, and purulent drainage from wounds or incisions. Treatment includes prompt administration of antibiotics and, in some cases, surgical intervention to remove infected tissue.

- Nonunion/Malunion: Some clients experience delayed bone healing that can impact recovery. When the normal healing process of a fracture is disrupted, it can result in impaired or nonunion of the bone. Ongoing pain, decreased mobility, and poor progression of healing in imaging studies are signs of nonunion or malunion of bone.

Diagnostic Testing

Diagnostic testing to identify a fracture typically includes radiography to identify the location and severity of the bone injury, as well as other tests based on the circumstances[20],[21]:

- X-rays provide a 2-D image of the bone, identifying the location and extent of the fracture. This is the most common test used to diagnose a fracture.

- If a complex fracture is suspected, a CT scan may also be ordered. A CT scan can provide better visualization of the bone and surrounding tissues by displaying cross-sectional images.

- MRI scans are helpful for providing detailed images of soft tissue, ligaments, tendons, and bones. MRI scans can provide more detailed images of fractures that may be more subtle, such as a stress fracture.

- Ultrasounds can also be useful for identifying fractures in children with better visualization of growth plates.

- If metastatic bone cancer is a suspected cause of a fracture, a bone scan may be ordered. The bone scan involves the injection of radioactive material into the bloodstream that collects in areas of high osteoblastic activity.

Nursing Diagnoses

Nursing diagnoses for clients with fractures focus on minimizing complications and restoring function. Common nursing diagnoses include the following:

- Acute Pain

- Impaired Physical Mobility

- Impaired Skin Integrity

- Anxiety

- Risk for Falls

Outcome Identification

Outcome identification includes setting short- and long-term goals and creating expected outcome statements customized for the client’s specific needs. Expected outcomes are statements of measurable action for the client within a specific time frame that are responsive to nursing interventions. Sample expected outcomes for a client diagnosed with a fracture are as follows:

- The client will report a decrease in pain intensity using a pain severity scale within one hour of receiving analgesics.

- The client will perform prescribed exercises demonstrating improved physical mobility within one week.

- The client will show signs of fracture healing within six weeks, including decreased swelling and increased mobility.

- The client will verbalize a reduction in anxiety levels related to the fracture, scoring below “5” on a standardized anxiety assessment tool within 24 hours.

- The client will demonstrate accurate use of assistive devices, showing no signs of instability or falls before discharge.

Interventions

Medical Interventions

Medical interventions for fractures aim to align the bones, promote healing, manage pain, prevent complications, and restore function. Interventions include fracture reduction, immobilization, medication therapy, physical therapy, and nutritional support.

Fracture Reduction

There are several types of procedures used to realign fractured bones:

- Closed Reduction: A nonsurgical procedure where the provider manipulates the fractured bones back into their proper position without making an incision. This procedure is often followed by immobilization with a cast, splint, or brace to help ensure the bones remain in the optimal position for healing.[22],[23]

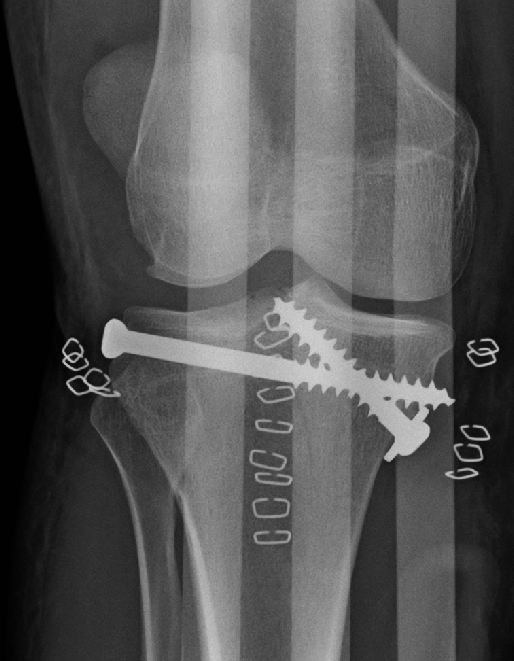

- Open Reduction and Internal Fixation (ORIF): Involves an incision for the surgical realignment of the fractured bones and then they are internally fixated (i.e., held together) with hardware like metal pins, plates, rods, or screws. After the bone heals, this hardware is not typically removed unless additional symptoms occur.[24],[25] See Figure 10.30[26] for an image of an ORIF.

- External Fixation: A surgical procedure where metal pins or screws are inserted into the bone above and below the fracture site and connected to an external frame to stabilize the fracture. This method is often used for severe open fractures, when swelling or other injuries make immediate internal fixation risky, or for fractures with delayed healing.[27],[28] See Figure 10.31[29] for an image of external fixation.

Immobilization

Immobilization involves application of a cast, splint, or brace to restrict movement of the affected limb or body part, allowing the bones to heal properly. See Figure 10.32[30] for an image of a cast.

Occasionally, traction may also be used by applying a pulling force to the affected limb or body part using weights and pulleys to align and immobilize the fracture and reduce muscle spasms.[31],[32] See Figure 10.33[33] for an image of a client with traction.

There are two different types of traction called skin and skeletal traction. Skin traction also known as Buck’s traction is utilized to decrease muscle spasms and align the bone until surgery or reduction can be performed. Skin traction involves the application of weights over the end of the bed as a pulling force. They are typically attached to a boot that is applied to the client. The size of the weight is prescribed by the provider. Skeletal traction is used for bone realignment and uses external pins that go through the skin to the bone to reduce the fracture.

View a supplementary YouTube video[34] on Buck’s traction: How To Apply Buck’s Traction and Education.

Traction Care

If a client has traction prescribed for a fracture, nurses perform focused assessments and interventions as summarized in the following box.

Traction Care[35]

- Regularly assess the traction setup to ensure the proper balance between the force applied by the traction and the countertraction force, which stabilizes the body part.

- Check the equipment regularly to verify that it remains intact, properly aligned, and functioning correctly.

- Collaborate with the health care team to ensure the prescribed traction force aligns with the treatment plan and the client’s condition.

- Ensure that weights are properly suspended and freely hanging, avoiding contact with the floor or the bed. Improperly placed or resting weights may disrupt the traction and compromise its effectiveness.

- Regularly check the weights for any signs of fraying in the ropes or malfunction in the pulley system.

Skin Inspection

- Perform frequent skin assessments around the traction site and bony prominences to identify any signs of skin breakdown, irritation, or pressure injuries.

- Maintain proper skin hygiene and implement measures to prevent pressure injuries, such as using specialized padding or positioning devices as directed.

Pin Care

- If the traction involves pins inserted into bone (as in skeletal traction), follow strict aseptic technique during pin care to prevent infections.

- Cleanse the pin sites as per the health care provider’s instructions and change dressings using sterile techniques.

Assessment of Neurovascular Status

- Assess neurovascular status frequently, including assessing pulses, sensation, and movement distal to the traction site.

- Record neurovascular assessments in the client’s chart, noting any changes or abnormalities to report to the health care provider promptly.

Education and Communication

- Educate the client and family members about the purpose of traction, skin care, potential complications, and the importance of adhering to prescribed positioning and movement restrictions.

- Report any concerns regarding traction setup, skin integrity, or changes in the client’s neurovascular status to the health care team promptly for timely intervention.

Medication Therapy

Pain medications, such as opioids or local anesthetics, may be prescribed to alleviate discomfort during the acute phase of a fracture. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) are avoided due to the risk of malunion of the fracture. Antibiotics may be prescribed for open fractures or for those repaired with surgery. Postoperatively, hospitalized clients are often prescribed anticoagulants to prevent deep vein thrombosis.

Physical Therapy and Occupational Therapy

Physical therapy helps restore range of motion and strength after a fracture. It includes exercises, stretching, and other modalities to promote healing, maintain strength, and regain mobility. Occupational therapy helps restore functioning and the ability to complete activities of daily living. Teaching about safe use of assistive devices, such as crutches and walkers, is also provided.

Nutritional Support

The client is encouraged to have an adequate intake of nutrients, especially calcium, vitamin D, and protein to support bone healing and strength.

Nursing Interventions

Nursing interventions focus on monitoring for potential complications and providing health teaching.

Monitoring for Complications

Nurses routinely assess neurovascular status (color, circulation, movement, and sensation) of the affected limb to detect signs of compromised circulation or nerve function. The client and their family members are educated about the signs of potential complications and when to seek immediate medical attention.

If a cast is placed, nurses perform the following focused assessments:

- Assess for any foul smell or discharge around the cast, indicating possible infection.

- Assess for sensory changes such as increased pain or sensations of tingling or burning, as these might indicate nerve compression, acute compartment syndrome, or other complications.

- Assess for decreased temperature, pulses, or capillary refill distal to the fracture, which might signify compromised circulation.

- Monitor for swelling above or below the cast, as well as movement limitations, which can signify circulation problems or complications with bone healing.

Health Teaching

Nurses teach clients about comfort measures and actions to prevent complications.

- Ice is typically prescribed by the health care provider for fractures to help with discomfort and reduce swelling. Generally, ice or a cold pack is on the affected area for 10 to 20 minutes at a time and repeated every one to two hours while awake for several days. A thin cloth should be placed between the ice and the skin.

- Elevation of a fractured extremity can reduce swelling and alleviate discomfort. If not contraindicated, the injured area should be placed on a pillow and elevated about the level of the heart when sitting or lying for several days.

- Safe use of assistive devices (i.e., crutches and walkers) or immobilization devices (i.e., casts and splints) is reinforced. If the client has a cast, teaching about cast care is provided. Read more about cast care in the following box.

- Early ambulation and/or range-of-motion exercises can prevent muscle atrophy, joint stiffness, and the development of deep vein thrombosis (DVT). Nurses collaborate with physical therapy to initiate a progressive exercise regimen to prevent muscle atrophy and aid in rehabilitation.

Health Teaching: Cast Care[36]

- Instruct the client to elevate the casted limb above heart level to minimize swelling and improve circulation.

- Monitor for signs of infection, compromised circulation, or nerve damage, and report any changes promptly.

- Emphasize infection prevention measures and circulation checks to the client, including signs of complications such as numbness, tingling, or color changes.

- Educate the client about the potential risks associated with immobilization, including muscle atrophy and joint stiffness.

- Regularly inspect the skin around the edges of the cast for redness, irritation, or breakdown that might indicate skin problems.

- Educate the client about the importance of keeping the cast dry to prevent skin irritation and the breakdown of the cast material.

- Advise against placing objects down into the cast, which could cause irritation or skin damage.

Evaluation

During the evaluation stage, nurses determine the effectiveness of nursing interventions for a specific client. The previously identified expected outcomes are reviewed to determine if they were met, partially met, or not met by the time frames indicated. If outcomes are not met or only partially met by the time frame indicated, the nursing care plan is revised. Evaluation should occur every time the nurse implements interventions with a client, reviews updated laboratory or diagnostic test results, or discusses the care plan with other members of the interprofessional team.

![]() RN Recap: Fracture

RN Recap: Fracture

View a brief YouTube video overview of fracture[37]:

- MedlinePlus [Internet]. (2016). Fractures. https://medlineplus.gov/fractures.html#summary ↵

- Campagne, D. (2022). Overview of fractures. Merck Manual Consumer Version. https://www.merckmanuals.com/home/injuries-and-poisoning/fractures/overview-of-fractures ↵

- American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons. (2021). Fractures (Broken bones). https://orthoinfo.aaos.org/en/diseases--conditions/fractures-broken-bones/ ↵

- “612_Types_of_Fractures.jpg” by OpenStax College is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- “Cdm hip fracture 343.jpg” by Booyabazooka is licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0 ↵

- NHS (UK). (2023). Hip fracture. https://www.nhs.uk/conditions/hip-fracture/ ↵

- Sheen, J. R., Mabrouk, A., Garla, V. V. (2023). Fracture Healing Overview. StatPearls [Internet]. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK551678/ ↵

- “613_Stages_of_Fracture_Repair.jpg” by OpenStax College is licensed under CC BY 3.0 ↵

- MedlinePlus [Internet]. (2016). Fractures. https://medlineplus.gov/fractures.html#summary ↵

- Singaram, S., & Naidoo, M. (2019). The physical, psychological and social impact of long bone fractures on adults: A review. African Journal of Primary Health Care & Family Medicine, 11(1), e1-e9. https://doi.org/10.4102/phcfm.v11i1.1908 ↵

- Campagne, D. (2022). Overview of fractures. Merck Manual Consumer Version. https://www.merckmanuals.com/home/injuries-and-poisoning/fractures/overview-of-fractures ↵

- Cleveland Clinic. (n.d.). Bone fractures. https://my.clevelandclinic.org/health/diseases/15241-bone-fractures ↵

- Torlincasi, A. M., Lopez, R. A., Waseem, M. (2023). Acute Compartment Syndrome. StatPearls [Internet]. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK448124/ ↵

- Pechar, J., & Lyons, M. M. (2016). Acute compartment syndrome of the lower leg: A review. The Journal for Nurse Practitioners: JNP 12(4), 265-270. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nurpra.2015.10.013 ↵

- “Compartment_Syndrome_Picture_Wikipedia.jpg” by CarrieRocks is licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0 ↵

- Torlincasi, A. M., Lopez, R. A., Waseem, M. (2023). Acute Compartment Syndrome. StatPearls [Internet]. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK448124/ ↵

- Campagne, D. (2022). Overview of fractures. Merck Manual Consumer Version. https://www.merckmanuals.com/home/injuries-and-poisoning/fractures/overview-of-fractures ↵

- American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons. (2021). Fractures (Broken bones). https://orthoinfo.aaos.org/en/diseases--conditions/fractures-broken-bones/ ↵

- Cleveland Clinic. (n.d.). Bone fractures. https://my.clevelandclinic.org/health/diseases/15241-bone-fractures ↵

- Villa-Forte, A. (2022). Tests for musculoskeletal disorders. https://www.merckmanuals.com/home/bone,-joint,-and-muscle-disorders/diagnosis-of-musculoskeletal-disorders/tests-for-musculoskeletal-disorders ↵

- Derby, R., & Beutler, A. (2023). General principles of acute fracture management. UpToDate. www.uptodate.com ↵

- Campagne, D. (2022. Overview of fractures. Merck Manual Consumer Version. https://www.merckmanuals.com/home/injuries-and-poisoning/fractures/overview-of-fractures ↵

- American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons. (2021). Fractures (Broken bones). https://orthoinfo.aaos.org/en/diseases--conditions/fractures-broken-bones/ ↵

- Campagne, D. (2022). Overview of fractures. Merck Manual Consumer Version. https://www.merckmanuals.com/home/injuries-and-poisoning/fractures/overview-of-fractures ↵

- American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons. (2021). Fractures (Broken bones). https://orthoinfo.aaos.org/en/diseases--conditions/fractures-broken-bones/ ↵

- “TibPlatRepair.png” by James Heilman, MD is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0 ↵

- Campagne, D. (2022). Overview of fractures. Merck Manual Consumer Version. https://www.merckmanuals.com/home/injuries-and-poisoning/fractures/overview-of-fractures ↵

- American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons. (2021). Fractures (Broken bones). https://orthoinfo.aaos.org/en/diseases--conditions/fractures-broken-bones/ ↵

- “Ilizarov_Apparatus_External_Fixator.JPG” by Pagemaker787 is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0 ↵

- “Plaster_of_Paris_Short_leg_cast.jpg” by Jonuscumgi is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0 ↵

- American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons. (2020). Care of casts and splints. https://orthoinfo.aaos.org/en/recovery/care-of-casts-and-splints/ ↵

- Choudhry, B., Leung, B., Filips, E., & Dhaliwal, K. (2020). Keeping the traction on in orthopaedics. Cureus, 12(8), e10034. https://doi.org/10.7759/cureus.10034 ↵

- “DA-SC-86-02998.jpeg” by SFC William Clay is in the Public Domain. Access for free at https://catalog.archives.gov/id/6398091 ↵

- Katie Copeland. (2020, March 12). How to apply buck's traction and education [Video]. YouTube. All rights reserved. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=dZNNOJEdecg ↵

- Choudhry, B., Leung, B., Filips, E., & Dhaliwal, K. (2020). Keeping the traction on in orthopaedics. Cureus, 12(8), e10034. https://doi.org/10.7759/cureus.10034 ↵

- American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons. (2020). Care of casts and splints. https://orthoinfo.aaos.org/en/recovery/care-of-casts-and-splints/ ↵

- Open RN Project. (2024, June 23). Health Alterations - Chapter 10 - Fracture [Video]. You Tube. CC BY-NC 4.0 https://youtu.be/bqoGJP8DSLs?si=mkhrigTxO0jzS4xr ↵

A break or disruption in the integrity of a bone.

Bone is broken but does not protrude the skin.

Bone is broken and pierces through the skin.

Bone is broken straight across.

Bone has twisted apart.

A bone is crushed into pieces.

One fragment of the bone is driven into the other, usually as a result of compression.

Bone is partially broken, a common fracture in children that occurs rarely in adults.

Bone is broken at an angle.

Small crack in a bone.

The bone breaks entirely into two or more separate pieces.

The bone cracks but doesn't break into separate pieces.

Typically occurs in vertebrae and involves the bone being crushed or collapsing, often seen in conditions like osteoporosis.

A fracture that occurs due to disease process.

Commonly referred to as a “broken hip”.

Increased pressure within a muscle compartment, resulting in reduced blood flow to the tissues within that compartment.

Acronymn to describe warning signs of Acute Compartment Syndrome.

A surgical procedure that relieves pressure within the compartment by making incisions through the fascia (connective tissue surrounding the compartment) to release the built-up pressure.

Type of shock caused by extensive blood loss and characterized by a rapid heart rate, low blood pressure, and altered consciousness.

Can arise from certain fractures, particularly long-bone fractures or bone with large amounts of marrow, such as the ribs, pelvis, and femur.

A nonsurgical procedure where the provider manipulates the fractured bones back into their proper position without making an incision.

Involves an incision for the surgical realignment of the fractured bones and then they are internally fixated (i.e., held together) with hardware like metal pins, plates, rods, or screws.

A surgical procedure where metal pins or screws are inserted into the bone above and below the fracture site and connected to an external frame to stabilize the fracture.

Application of a cast, splint, or brace to restrict movement of the affected limb or body part, allowing the bones to heal properly.

Application of a pulling force to the affected limb or body part using weights and pulleys to align and immobilize the fracture and reduce muscle spasms.

Skin traction that involves the application of weights over the end of the bed as a pulling force.