9.7 Seizures and Epilepsy

A seizure is abnormal transient discharges of neurons within the brain that are sudden, excessive, and uncontrolled. During a seizure, many neurons send signals at the same time, much faster than normal. This surge of excessive electrical activity may cause involuntary movements, sensations, emotions, and/or behaviors. The disturbance of normal nerve cell activity may cause a loss of awareness. Some people recover immediately after a seizure, while others may take minutes to hours to feel like themselves again. During this time, they may feel tired, sleepy, weak, or confused.[1]

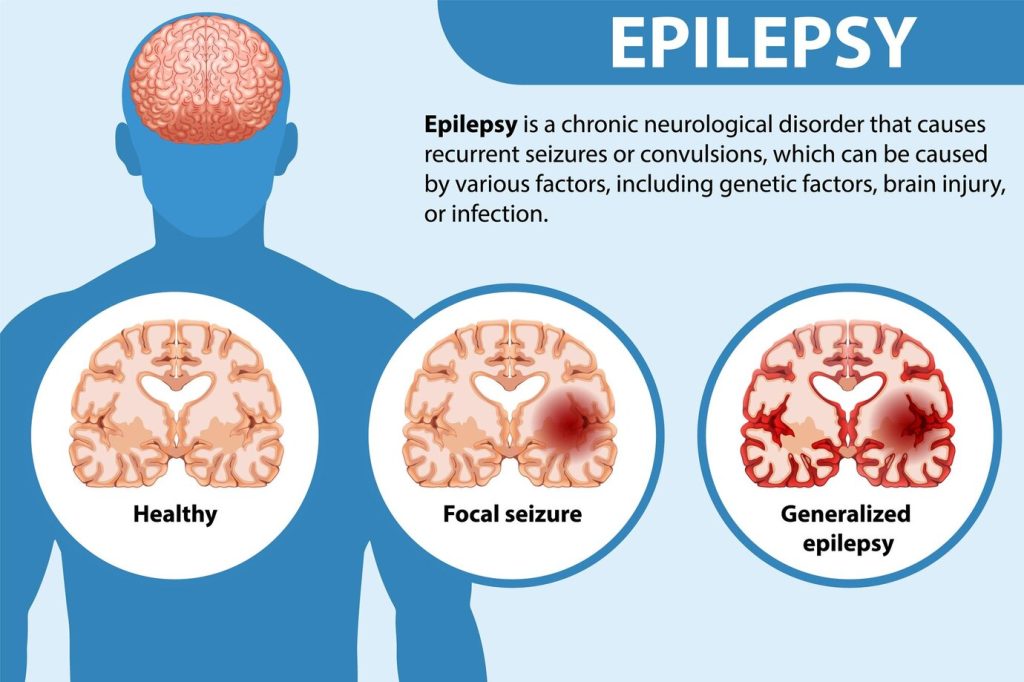

Most seizures are idiopathic, with no known cause. Seizures can also be caused by other medical conditions, such as a brain tumor, high fever, or hyponatremia. Epilepsy is a chronic disorder that is defined by at least two unprovoked seizures occurring at least 24 hours apart and in which groups of nerve cells, or neurons, in the brain sometimes send the wrong signals and cause recurrent, unpredictable, and unprovoked seizures.

Status epilepticus refers to a seizure lasting more than five minutes or two more sequential seizures without full recovery of consciousness between the seizures. Seizures lasting more than five minutes damage neurons and are unlikely to end on their own, requiring immediate emergency medical care.[2]

Pathophysiology

Seizures are caused by an abnormality in electrical neuron activity, an imbalance of the neurotransmitter GABA, or a combination of both conditions. When there is an imbalance between inhibition and excitatory conditions within the CNS, a seizure occurs.

View a supplementary YouTube video[3] on epilepsy from the Mayo Clinic: What is epilepsy? A Mayo Clinic expert explains.

Types of Seizures

Seizures are divided into three broad categories called partial (focal), generalized, and unclassified seizures. See an illustration of partial (focal) and generalized seizures in Figure 9.20.[4] Each of these categories will be further discussed in the following subsections.

Partial Seizures

Partial seizures, also known as focal seizures, occur within one cerebral hemisphere of the brain. Partial seizures are further subdivided into two main classes called complex partial seizures and simple partial seizures. In some instances, a partial seizure can develop into a generalized tonic, clonic, or tonic-clonic seizure. Partial seizures are more common in adult clients and are generally less responsive to medical treatment than other types of seizures.

- Complex partial seizures: These seizures often occur in the temporal lobe and may be called psychomotor seizures due to the function of this part of the brain. Semi-coordinated, repetitive motor movements occur, and loss of consciousness may occur for one to three minutes. Clients are unaware of their environment and may wander at the beginning of the seizures. In the postictal period (time after the seizure), clients may have amnesia.

- Simple partial seizures: The client remains conscious throughout a simple partial seizure. An aura (unusual sensation) occurs before the seizure and is often described as a “deja vu” feeling, a perceived offensive smell, or sudden onset of pain. The client may also experience one-sided movement of an extremity or usual sensations. Autonomic changes in heart, skin flushing, or epigastric pain may also occur.

Generalized Seizures

Generalized seizures involve abnormal electrical activity in both cerebral hemispheres of the brain. Generalized seizures are classified as tonic, clonic, tonic-clonic, myoclonic, and atonic:

- Tonic: Usually lasts for 30 seconds to several minutes and involves an abrupt increase in muscle tone, loss of consciousness, and possible changes in heart rate, blood pressure, and respirations.

- Clonic: Muscle contractions and relaxation last several minutes.

- Tonic-clonic: Last approximately two to five minutes; begins with a tonic phase with stiffening and rigidity of the muscles (typically of arms and legs) and then followed by immediate loss of consciousness and rhythmic jerking of all extremities. The client may bite their tongue and become incontinent of urine and feces.

- Myoclonic: A brief episode of jerking or stiffening of the extremities, either in muscle groups or isolated; contractions can be symmetrical or asymmetrical.

- Atonic (akinetic): A sudden loss of muscle tone for a few seconds and followed by postictal (period after seizure) confusion. Often, this type of seizure causes the person to fall, causing injury. This type of seizure is most resistant to drug therapy.

View a supplementary YouTube video[5] of tonic-clonic seizure: Tonic clonic seizure.

Unclassified Seizures

Unclassified seizures occur for no known reason so are also known as idiopathic. They compromise about half of all seizure activity and may have symptoms of both generalized or partial seizures. Primary epilepsy is not associated with any specific cause, but genetic factors seem to play a role. Secondary seizures are caused by other conditions, such as a brain tumor or trauma. Other potential causes of unclassified seizures include the following:

- Alcohol withdrawal

- Alzheimer’s disease

- Strokes, heart attacks, and other cardiovascular conditions that deprive the brain of oxygen or cause bleeding in the brain

- Brain inflammation or swelling

- Infections such as meningitis, HIV-related infections, and viral encephalitis

- High fever

- Metabolic disorders

- Electrolyte disturbances (e.g., hypoglycemia, hyperkalemia, hyponatremia)

Phases of Seizures

Depending on the seizure category, it may occur in multiple phases:

- Prodromal or preictal phase: Sensations or behavior changes that precede a seizure

- Aural phase: A sensory warning that is similar each time a seizure occurs

- Ictal phase: The phase from the first symptoms to the end of seizure activity

- Postictal phase: The recovery period after the seizure

Seizure Triggers

Seizure triggers are conditions that can provoke seizures in people diagnosed with epilepsy and taking medications. Triggers include the following conditions[6]:

- Stress

- Increased physical activity

- Excessive fatigue

- Alcohol or caffeine consumption

- Dehydration or missing meals

- Exposure to toxins or poisons, including lead, carbon monoxide, illicit drugs, and very large doses of prescription medications

- Hormonal changes associated with the menstrual cycle

- Sleep deprivation

- Visual stimulation such as flashing lights or moving patterns

Assessment

Interviewing the client and/or family and obtaining a thorough history are essential for management of care, including data such as how many seizures has the person had; how long they lasted; any pattern of occurrence; signs and symptoms before, during, and after a seizure; the presence of an aura; and if there was loss of consciousness. Ask if the client is currently taking any prescription drugs, herbal supplements, or using alcohol or drugs. Inquire if the client has any other medical conditions such as hypertension, diabetes, stroke, or history of head injury.

Common Laboratory and Diagnostic Tests

Diagnosis of seizure activity is made through a complete history and physical examination, as well as diagnostic testing. Diagnostic tests are ordered by health care providers to rule out possible causes of seizure activity and/or confirm a diagnosis of epilepsy. Common diagnostic tests include an electroencephalogram (EEG), CT scan, MRI, or a SPECT/PET scan. EEG monitoring can help determine the intrinsic cause of the seizure.

If a seizure occurs, blood tests, such as serum electrolyte levels, blood cell count, glucose, toxicology/drug screen, and levels of prescribed drugs such as phenytoin or phenobarbital, are typically performed to assess for possible causes. Review information about these tests under the “General Assessment of the Nervous System” section.

Nursing Diagnosis

Common nursing diagnoses for clients with seizures include the following[7]:

- Risk for Injury

- Risk for Impaired Swallowing

- Risk for Ineffective Airway Clearance

- Fear

- Anxiety

- Ineffective Coping

- Deficient Knowledge

Outcome Identification

Overall goals for clients with seizures and epilepsy focus on preventing seizures and injuries, as well as promoting effective coping and self-management of this chronic disease.

Examples of outcome criteria for clients with seizures include the following[8]:

- After the teaching session, the client and their caregiver(s) will identify actions to take when a seizure occurs to maintain safety and prevent injury.

- After the teaching session, the client and their caregiver(s) will list three possible triggers that may cause a seizure to occur.

- After the teaching session, the client and their caregiver(s) will verbalize understanding of the treatment regimen to prevent seizure activity.

- After the teaching session, the client will list three preferred coping strategies to maintain emotional wellness.

- During a seizure, the client will maintain a patent airway.

Interventions

Medical Interventions

The goals of medical treatment are to stop seizures when they occur as quickly as possible, ensure adequate cerebral oxygenation during seizure activity, and maintain a seizure-free state.

When a seizure occurs that requires medical treatment, medications such as IV lorazepam, diazepam, or midazolam may be administered as prescribed. Ongoing cardiac and respiratory monitoring (including continuous pulse oximetry) is performed to monitor for side effects of medications administered to stop the seizure. Additional information about medications is provided under the “Medication Therapy” subsection. If the airway is patent, oxygen may be administered via a nasal cannula or mask. However, if the client is exhibiting signs of airway obstruction, intubation may be performed with oxygen administered via the artificial airway. Suction is implemented, as needed, to remove excess secretions and maintain a patent airway. After a seizure occurs, antiepileptic medications such as levetiracetam, phenytoin, and phenobarbital may be prescribed to maintain a seizure-free state. IV infusion of fluids is usually prescribed to replace fluids and provide appropriate electrolyte replacement.

Medication Therapy

Current evidence does not support starting anti-seizure medications following a first-time seizure because it does not change the quality of life. However, clients who experience a seizure should see a neurologist within 15 days. Following a new onset seizure, clients are counseled about risk factors related to starting an anticonvulsant. Medication does not cure the disorder, so the objective of pharmacologic treatment is to achieve seizure control with minimal side effects.[9]

There are several medications available to control seizures. A single medication is typically prescribed to prevent seizure activity and then the dose is titrated until symptoms are resolved, the maximal dose is reached, or signs of drug toxicity occur. Phenytoin is one of the oldest anti-seizure medications that can also be administered IV for status epilepticus, but it must be administered slowly while the client is on cardiac monitoring due to its potential for arrhythmias.

For some anti-seizure medications, blood levels are routinely monitored to prevent toxicity. Changing to another medication may be required if seizure activity is not controlled or drug toxicity occurs. Additionally, medication dosage and/or frequency of administration may require adjustment to meet the body’s needs in times of illness, weight changes, or increased stress. A client should be educated to never stop taking the medication without consulting with the provider because doing so could cause increased frequency of seizures or status epilepticus.

The type of medication prescribed is based on the type of seizure and the safety/effectiveness of the medication(s). If prescribed medications are taken as directed, seizure activity can often be controlled. However, some clients with epilepsy do not respond to drug management and require surgery to reduce seizure frequency or provide complete seizure control. Table 9.7 summarizes common anticonvulsants, their side effects, and potential toxic effects.

Table 9.7. Common Anticonvulsants[10]

| Medication | Dose-Related Side Effects | Toxic Effects |

|---|---|---|

| Carbamazepine | Drowsiness, unsteadiness, drowsiness, blurred vision, nausea/vomiting, or mild leukopenia. | Stevens-Johnson syndrome (a rare, serious disorder of the skin and mucous membranes), toxic epidermal necrolysis (extensive exfoliation of the epidermis and mucous membrane, which may result in sepsis and death), severe leukopenia, aplastic anemia, pancytopenia, and hepatitis |

| Oxcarbazepine | Dizziness, headache, ataxia, nausea, rash, double vision, tremor, somnolence, and/or hyponatremia. The latter effect is thought to be secondary to the syndrome of inappropriate secretion of antidiuretic hormone (SIADH) and may occur in 25-75% of clients. | Hepatotoxicity |

| Phenytoin | Arrhythmias, visual problems, gum enlargement, unclear articulation of speech, nystagmus (rapid, uncontrollable eye movements), abnormal hair growth, or decreased bone density. | Severe skin reaction, drowsiness, peripheral neuropathy, ataxia, and blood or bone marrow disorders. |

| Phenobarbital | Sedation, diplopia, irritability, or ataxia. | Anemia and skin rash |

| Lamotrigine | Drowsiness, somnolence, fatigue, weight gain, ataxia, or nausea. | Stevens-Johnson syndrome |

| Levetiracetam | Somnolence, fatigue, or dizziness. | Stevens-Johnson syndrome |

| Gabapentin | Fatigue, ataxia, weight gain, drowsiness, or dizziness. | Leukopenia and hepatotoxicity |

| Valproate | Nausea, vomiting, weight gain, tremor, hair loss, or menstrual irregularities. | Hepatotoxicity, skin rash, and nephritis |

| Topiramate | Fatigue, confusion, ataxia, anorexia, weight loss, depression, or somnolence. | Nephrolithiasis (kidney stones) and metabolic acidosis |

| Ethosuximide | Nausea, vomiting, headache, or gastric upset. | Skin rash, hepatitis, and systemic lupus erythematosus |

| Clonazepam | Behavior changes, alopecia, palpitations, or drowsiness. | Hepatotoxicity, thrombocytopenia, bone marrow failure, and ataxia |

Surgical Interventions

Surgery may be required for clients with epilepsy from intracranial tumors, cysts, abscesses, or vascular anomalies, or their seizures are unresponsive to medication therapy. If the seizure can be located to a specific, well-defined area of the brain, the area may be excised without producing significant neurologic deficits. This type of surgery is called a lobectomy.

As adjunct treatment to medications, a vagal nerve stimulator may be implanted below the clavicle. The device is connected to the vagus nerve in the cervical area and delivers electrical signals to the brain to reduce and/or control seizure activity.

Nursing Interventions

Nursing interventions for clients experiencing seizures focus on improving safety and preventing injury, monitoring for potential complications, providing health teaching, and providing psychosocial support to enhancing coping mechanisms. The following box summarizes nursing interventions during and after a seizure.

Nursing Interventions During a Seizure[11]

- If a client experiences an aura prior to a seizure, attempt to get the client to a safe, private place.

- Provide privacy during a seizure.

- Ease the client to the floor if not currently in bed.

- If the client is in bed, remove extra pillows and raise the side rails.

- If the client is on the floor, protect the client’s head with a pad and prevent it from hitting the floor.

- Loosen constrictive clothing and remove any eyeglasses.

- Push aside any furniture or objects that could cause client injury during the seizure.

- Do not attempt to open or pry the client’s jaws if they are clenched in a spasm. Do not insert anything into the mouth because this may cause broken teeth and/or injury to mouth/tongue.

- Do not restrain the client during the seizure, and do not attempt to stop the client’s movements.

- Record the start and end times of the seizure.

- If a client experiences status epilepticus, call for emergency assistance and notify the health care provider. Administer oxygen per agency policy until help arrives.

- Observe for these items during the seizure:

- Presence of aura

- Changes in pupil size and any eye deviation

- Level of consciousness

- Presence of apnea, cyanosis, and drooling

- Incontinence

- Eye flutter or blinking

- Tongue or lip biting

- Lip smacking

Nursing Interventions After a Seizure

- Keep the client on their side to prevent aspiration.

- Ensure the airway is open and patent.

- Assess vital signs.

- Perform neurological checks.

- Allow the client to rest.

- Document observations made while the seizure was occurring.

- Monitor for increased frequency or duration due to potential of apneic periods that may occur during or immediately following a generalized seizure.

- Because there is often a period of confusion after a tonic-clonic seizure, maintain a safe environment.

- On awakening, reorient the client to the environment.

- If a client becomes agitated upon awakening, use calm, nonthreatening communication.

- Document the length of time it takes the client to return to a preseizure state.

When caring for a client with a history of seizures in an inpatient setting, the nurse implements seizure precautions. Oxygen and suction equipment should be readily accessible at the bedside. Padded side rails may be implemented, based on agency policy. The bed should be kept in the lowest position.

Health Teaching

Providing health teaching to the client and their family members/caregivers promotes positive coping and self-care management. Health teaching should include the following topics:

- Reinforcing medication therapy information and the importance of not stopping medication without talking to the health care provider. Include written instructions for what to do if a dose is missed and to contact their health care provider if side effects occur. Reinforce the importance of routinely having therapeutic blood levels drawn as prescribed. Advise them to not take over-the-counter medications or supplements without first consulting with the health care provider.

- Wearing a medical alert bracelet or necklace to identify the presence of a seizure disorder.

- Attending follow-up appointments with their health care provider/neurologist as directed.

- Ensuring the family member or significant other knows how to respond in the event of seizure, including when to call emergency services and when to notify the health care provider.

- Following state laws concerning driving and operating machinery.

- Avoiding alcohol and excessive fatigue because these factors can trigger seizures.

- Eating a healthy, balanced diet; getting proper rest; and using stress management techniques to minimize risk of breakthrough seizures.

- Keeping a seizure diary and bringing it to follow-up medical appointments.

- Providing community resources and support for clients and their family members, such as the Epilepsy Foundation.

Evaluation

Evaluation of client outcomes refers to the process of determining whether or not client outcomes were met by the indicated time frame. This is done by reevaluating the client as a whole and determining if their outcomes have been met, partially met, or not met. If the client outcomes were not met in their entirety, the care plan should be revised and reimplemented. Evaluation of outcomes should occur each time the nurse assesses the client, examines new laboratory or diagnostic data, or interacts with a family member or other member of the client’s interdisciplinary team.

![]() RN Recap: Seizures and Epilepsy

RN Recap: Seizures and Epilepsy

View a brief YouTube video overview of seizures and epilepsy[12]:

- National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke. (n.d.). Epilepsy and seizures. https://www.ninds.nih.gov/health-information/disorders/epilepsy-and-seizures ↵

- National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke. (n.d.). Epilepsy and seizures. https://www.ninds.nih.gov/health-information/disorders/epilepsy-and-seizures ↵

- Mayo Clinic. (2021, November 18). What is epilepsy? A Mayo Clinic expert explains [Video] YouTube. All rights reserved. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=WjRIzsy97hk ↵

- “Informative poster of epilepsy” by brgfx, via Freepik is licensed under CC0 ↵

- Epilepsy Toronto. (2016, January 19). Tonic clonic seizure [Video]. YouTube. All rights reserved. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=FBEj9H42fa4 ↵

- National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke. (n.d.). Epilepsy and seizures. https://www.ninds.nih.gov/health-information/disorders/epilepsy-and-seizures ↵

- Herdman, T. H., Kamitsuru, S., & Lopes, C. T. (Eds.). (2020). Nursing diagnoses: Definitions and classification, 2021-2023 (12th ed.). Thieme. ↵

- Epsy. (2023). Nursing interventions for seizures. https://www.epsyhealth.com/seizure-epilepsy-blog/nursing-interventions-for-seizures ↵

- Al Sawaf. A., Arya, K., Murr, N. I. (2023). Seizure Precautions. StatPearls [Internet]. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK536958/ ↵

- Subbarao, B. S., Silverman, A., Eapen, B. C. (2023). Seizure Medications. StatPearls [Internet]. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK482269/ ↵

- Al Sawaf. A., Arya, K., Murr, N. I. (2023). Seizure Precautions. StatPearls [Internet]. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK536958/ ↵

- Open RN Project. (2024, June 23). Health Alterations - Chapter 9 - Seizures and epilepsy [Video]. You Tube. CC BY-NC 4.0 https://youtu.be/N3HxkFsgABw?si=gsM6uA3okBxFuiNX ↵

Abnormal transient discharges of neurons within the brain that are sudden, excessive, and uncontrolled.

A chronic disorder that is defined by at least two unprovoked seizures occurring at least 24 hours apart and in which groups of nerve cells, or neurons, in the brain sometimes send the wrong signals and cause recurrent, unpredictable, and unprovoked seizures.

Refers to a seizure lasting more than five minutes or two more sequential seizures without full recovery of consciousness between the seizures.

Also known as focal seizures, occur within one cerebral hemisphere of the brain.

These seizures often occur in the temporal lobe and may be called psychomotor seizures due to the function of this part of the brain.

Time after the seizure.

A seizure in which the client remains conscious throughout.

Unusual sensation occurs before the seizure and is often described as a “deja vu” feeling, a perceived offensive smell, or sudden onset of pain.

Involve abnormal electrical activity in both cerebral hemispheres of the brain.

Usually lasts for 30 seconds to several minutes and involves an abrupt increase in muscle tone, loss of consciousness, and possible changes in heart rate, blood pressure, and respirations.

Muscle contractions and relaxation last several minutes.

Last approximately 2-5 minutes; begins with a tonic phase with stiffening and rigidity of the muscles (typically of arms and legs) and then followed by immediate loss of consciousness and rhythmic jerking of all extremities.

A brief episode of jerking or stiffening of the extremities, either in muscle groups or isolated; contractions can be symmetrical or asymmetrical.

A sudden loss of muscle tone for a few seconds and followed by postictal (period after seizure) confusion.

Seizures occur for no known reason so are also known as idiopathic.

Sensations or behavior changes that precede a seizure.

A sensory warning that is similar each time a seizure occurs.

The phase from the first symptoms to the end of seizure activity.

The recovery period after the seizure.

Conditions that can provoke seizures in people diagnosed with epilepsy and taking medications.

A rare, serious disorder of the skin and mucous membranes.

Extensive exfoliation of the epidermis and mucous membrane, which may result in sepsis and death.