6.6 Diseases and Disorders of the Male Reproductive System

Benign Prostatic Hypertrophy

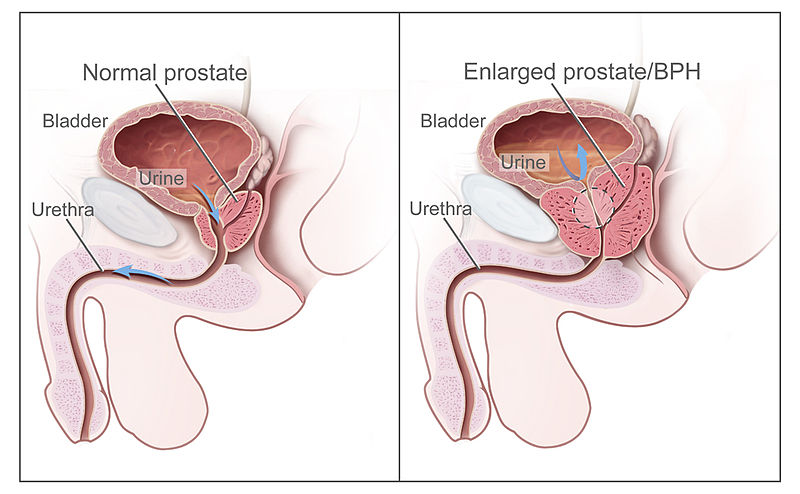

Benign prostatic hyperplasia (bē-NĪN prŏs-TĂT-ĭk hī-pĕr-PLĀ-zhē-ă) (BPH) refers to enlargement of the prostate that is not cancerous. See Figure 6.4[1] for an illustration of BPH. BPH is a common condition in males aged 50 and older. The prostate presses against the urethra, causing it to narrow. Eventually, the bladder becomes weak from trying to pass urine through the narrowed urethra. It loses its ability to completely empty, leaving some urine in the bladder called urinary retention. The inability to completely empty the bladder causes many of the symptoms associated with BPH, such as a frequent and intense urge to urinate, urinating frequently at night, difficulty starting a urine stream or a weak stream, and a sensation that the bladder has not emptied completely. If urinary retention is not addressed, it can cause complications such as urinary tract infections, bladder damage, and kidney damage.[2]

A health care provider may order several types of medical tests to diagnose BPH, such as urodynamic testing or a cystoscopy.[3] Review information about these tests in the “Medical Specialists, Diagnostic Testing, and Procedures Related to the Urinary System” section in the “Urinary System Terminology” chapter.

BPH may be treated with medications or transurethral (trans-ū-RĒ-thrăl) procedures where an instrument is inserted through the urethra to widen the urethra or destroy part of the prostate with heat. Transurethral microwave thermotherapy (trans-ū-RĒ-thrăl MĪ-krō-wāv THUR-mō-THĔR-ă-pē) (TUMT) eliminates excess tissue present in benign prostatic hyperplasia by using heat generated by microwave.

Surgery may be performed when symptoms are severe, other treatments haven’t helped, or a complication has developed such as bladder damage. Surgeries remove part or all of the prostate or make cuts in the prostate to take pressure off the urethra.[4] For example, transurethral incision of the prostate (trans-ū-RĒ-thrăl in-SIZH-ŭn ŏv thĕ PRŌS-tāt) (TUIP) is a procedure that widens the urethra by making a few small incisions in the bladder neck and the prostate gland. Transurethral resection of the prostate (trans-ū-RĒ-thrăl rĭ-SĔK-shŭn ŏv thĕ PRŌS-tāt) (TURP) is the surgical removal of pieces of the prostate gland by using an instrument inserted through the urethra.

Cancer

Prostate Cancer

Prostate cancer (PROS-tāt KAN-sĕr), cancer of the prostate gland, is the second most common cancer occurring in men. Prostate cancer is most common in older men. In the U.S., about 1 out of 8 men will be diagnosed with prostate cancer. Prostate cancer usually grows very slowly, so treating it before symptoms occur may not improve men’s health or help them live longer.[5]

Symptoms of prostate cancer are similar to benign prostatic hypertrophy (BPH), such as trouble starting a urine stream and frequent urination, especially at night, and trouble emptying the bladder. Symptoms of advanced prostate cancer that have metastasized to other areas of the body include pain in the back, hips, or pelvis that doesn’t go away, shortness of breath, fatigue, fast heartbeat, dizziness, or pale skin caused by anemia.[6]

Diagnostic testing for prostate cancer may include the following[7]:

- Digital rectal exam (dĭj-ĭ-tăl RĔK-tăl ĕgz-ăm): An exam where the health care provider inserts a lubricated, gloved finger into the rectum and feels the prostate through the rectal wall to assess size, lumps, or other abnormal areas.

- Pelvic lymphadenectomy (PĔL-vĭk lim-fad-ĕ-NEK-tō-mē): A surgical procedure to remove the lymph nodes in the pelvis. A pathologist views the tissue under a microscope to look for cancer cells.[8]

- Prostate-specific antigen (PRŌS-tāt spĕ-SIF-ĭk AN-tĭ-jĕn) (PSA): A test that measures the level of PSA in the blood, a substance made by the prostate that may be found in higher-than-normal amounts in the blood of men who have prostate cancer. PSA levels may also be elevated in men who have BPH or prostatitis, so it is not a very reliable test.

- PSMA PET scan (PSMA PĒ-Ē-TĔ skăn): An imaging procedure that is used to help find prostate cancer cells that have spread outside of the prostate, into bone, lymph nodes, or other organs. For this procedure, a cell-targeting molecule linked to a radioactive substance is injected into the body and travels through the blood. It attaches to a protein called prostate-specific membrane antigen (PSMA) that is found on the surface of prostate cancer cells. A PET scanner detects high concentrations of the radioactive molecule and shows where the prostate cancer cells are in the body.

- Seminal vesicle biopsy (SEM-ĭ-năl VES-ĭ-kĕl BĪ-ŏp-sē): The removal of fluid from the seminal vesicles using a needle that is then viewed under a microscope by a pathologist to look for cancer cells.[9]

- Transrectal ultrasound (trans-RĔK-tăl ŬL-tră-sound): A procedure in which a probe that is about the size of a finger is inserted into the rectum to check the prostate. The probe is used to bounce high-energy sound waves (ultrasound) off internal tissues or organs and make echoes. The echoes form a picture of body tissues called a sonogram. Transrectal ultrasound may also be used during a biopsy procedure called transrectal ultrasound guided biopsy (trăns-RĔK-tăl ŬL-tră-sound GĪ-ded BĪ-ŏp-sē).

- Transrectal MRI (trans-RĔK-tăl ĕm-ĀR-ĀĪ): A procedure that uses a strong magnet, radio waves, and a computer to make a series of detailed pictures of areas inside the body. A probe that gives off radio waves is inserted into the rectum near the prostate. This helps the MRI machine make clearer pictures of the prostate and nearby tissue. A transrectal MRI is done to find out if the cancer has spread outside the prostate into nearby tissues. Transrectal MRI may also be used during a biopsy procedure. This is called transrectal MRI guided biopsy (trăns-RĔK-tăl MRĪ GĪ-ded BĪ-ŏp-sē).

- Transrectal biopsy (trans-RĔK-tăl BĪ-ŏp-sē): The removal of tissue from the prostate by inserting a thin needle through the rectum and into the prostate. This procedure may be done using transrectal ultrasound or transrectal MRI to help guide where samples of tissue are taken from. A pathologist views the tissue under a microscope to look for cancer cells.

If prostate cancer is diagnosed, additional testing to check for metastasis may include bone scan, MRI, or CT scans. Read more about these diagnostic tests in the “Medical Specialists, Diagnostic Testing, Procedures, and Equipment Related to the Respiratory System.”

Treatment

There are several types of treatment for patients with prostate cancer, depending on the stage of the cancer and if it has metastasized (i.e., spread to other areas of the body)[10]:

- Watchful waiting

- Surgery

- Radiation therapy and radiopharmaceutical therapy

- Hormone therapy

- Chemotherapy

- Targeted therapy

- Immunotherapy

Watchful Waiting

Watchful waiting refers to treatment used for older men whose prostate cancer is found during a screening test, but do not have signs or symptoms. Watchful waiting means closely monitoring a patient’s condition without any treatment unless signs or symptoms appear, or test results change. Treatment is provided to relieve symptoms and improve quality of life.[11]

Surgery

There are many types of surgeries performed to treat prostate cancer[12]:

- Radical prostatectomy (RAD-ĭ-kăl prŌS-tă-TĔK-tŏ-mē): A surgical procedure to remove the prostate, surrounding tissue, and seminal vesicles. Removal of nearby lymph nodes may be done at the same time to check for possible metastasis. The main types of radical prostatectomy are as follows:

- Open radical prostatectomy (OPEN RAD-ĭ-kăl prŌS-tă-TĔK-tŏ-mē): An incision (cut) is made in the retropubic area (lower abdomen) or the perineum (the area between the anus and scrotum). Surgery is performed through the incision.

- Radical laparoscopic prostatectomy (RAD-ĭ-kăl lăp-ă-RŎS-kŏ-pĭk prŌS-tă-TĔK-tŏ-mē): Several small incisions (cuts) are made in the wall of the abdomen. A laparoscope (a thin, tube-like instrument with a light and lens for viewing) is inserted through one opening to guide the surgery. Surgical instruments are inserted through the other openings to do the surgery.

- Robot-assisted laparoscopic radical prostatectomy (ROH-bot ă-SĬS-tĕd lăp-ă-RŎS-kŏ-pĭk RAD-ĭ-kăl prŌS-tă-TĔK-tŏ-mē): Several small cuts are made in the wall of the abdomen, as in radical laparoscopic prostatectomy. The surgeon inserts an instrument with a camera through one of the openings and surgical instruments through the other openings using robotic arms. The camera gives the surgeon a three-dimensional view of the prostate and surrounding structures. The surgeon uses the robotic arms to do the surgery while sitting at a computer monitor near the operating table.

- Pelvic lymphadenectomy (PĔL-vĭk lim-fad-ĕ-NEK-tō-mē): Lymph nodes are removed from the pelvis for examination under a microscope by a pathologist who looks for cancer cells. If the lymph nodes contain cancer, the doctor may not remove the prostate and may recommend other treatment.

- Transurethral resection of the prostate (trans-ū-RĒ-thrăl rĭ-SĔK-shŭn ŏv thĕ PRŌS-tāt) (TURP): TURP is a surgical procedure to remove tissue from the prostate using a resectoscope (a thin, lighted tube with a cutting tool) inserted through the urethra. This procedure is done to treat benign prostatic hypertrophy, and it is sometimes done to relieve symptoms caused by a tumor in the prostate gland before other cancer treatment is given. TURP may also be done in men who cannot have a radical prostatectomy because their tumor is only in the prostate.

Radiation Therapy and Radiopharmaceutical Therapy

Radiation therapy (RĀ-dē-Ā-shŭn THĔR-ă-pē) uses high-energy X-rays or other types of radiation to kill cancer cells or keep them from growing. There are different types of radiation therapy[13]:

- External radiation therapy uses a machine outside the body to send radiation toward the area of the body with cancer. A computer may be used to make a three-dimensional (3-D) picture of the tumor and shape the radiation beams to fit the tumor. This allows a high dose of radiation to reach the tumor and causes less damage to nearby healthy tissue.

- Internal radiation therapy uses a radioactive substance sealed in needles, seeds, wires, or catheters that are placed directly into or near the cancer. In early-stage prostate cancer, radioactive seeds are placed in the prostate using needles that are inserted through the skin between the scrotum and rectum. The placement of the radioactive seeds in the prostate is guided by images from transrectal ultrasound or computed tomography (CT). The needles are removed after the radioactive seeds are placed in the prostate.

- Radiopharmaceutical therapy (RĀ-dē-ō-far-mă-SOO-tĭ-kăl THĔR-ă-pē) uses a radioactive substance to treat metastatic prostate cancer that has spread to the bone.

Hormone Therapy

Hormone therapy (HOR-mōn THĔR-ă-pē), also referred to as anti-androgen therapy, reduces the amount of testosterone or blocks its action to stop prostate cancer cells from growing. Hormone therapy includes medications, surgery, or other hormones. Orchiectomy (or-kē-EK-tŏ-mē) is the surgical removal of one or both testicles, the main source of testosterone, to decrease the amount of hormone being made.[14]

Chemotherapy

Chemotherapy (KĒ-mō-THĔR-ă-pē) uses medications to stop the growth of cancer cells, either by killing the cells or by stopping them from dividing. When chemotherapy is taken by mouth or injected into a vein or muscle, the drugs enter the bloodstream and can reach cancer cells throughout the body.[15]

Targeted Therapy

Targeted therapy (TAR-gĕt-ed THĔR-ă-pē) uses medications or other substances to identify and attack specific cancer cells. Targeted therapies usually cause less harm to normal cells than chemotherapy or radiation therapy.[16]

Immunotherapy

Immunotherapy (ĭm-yū-nō-THĔR-ă-pē) uses the patient’s immune system to fight cancer. Substances made by the body or made in a laboratory are used to boost, direct, or restore the body’s natural defenses against cancer.[17]

Testicular Cancer

Testicular cancer (tĕs-TĬK-ū-lăr KAN-sĕr) is cancer that begins in the cells that make sperm in the testicle. It is rare and is most frequently diagnosed in men ages 20 to 34. Most testicular cancers can be cured, even if diagnosed at an advanced stage. Common symptoms of testicular cancer are a painless lump in the testicle, a dull ache in the lower abdomen or the groin, a sudden build-up of fluid in the scrotum, and pain in a testicle or in the scrotum. Diagnostic tests include an ultrasound of the testes and blood tests for tumor markers. Treatment includes inguinal orchiectomy (IN-gwĭ-năl or-kē-EK-tŏ-mē), a procedure to remove the entire testicle through an incision in the inguinal region of the groin.[18]

Erectile Dysfunction (ED)

Erectile dysfunction (ĭ-RĒK-tīl dĭs-FŬNK-shŏn) (ED) is the inability to achieve or maintain an erection. ED is a common condition as men age, with 40% of men at age 40 and up to 70% of men by age 70 years experiencing ED. ED is also associated with side effects of some medications and many medical disorders such as high blood pressure, diabetes, cardiovascular disease, kidney disease, prostate disorders, and low testosterone levels. ED may be treated with medications or an implanted device.[19]

Hydrocele

A hydrocele (HĪ-drŏ-sēl) is a type of swelling in the scrotum, the pouch of skin that holds the testicles. This swelling happens when fluid collects in the thin sac that surrounds a testicle. Hydroceles are common in newborns. They often go away without treatment by age one.[20]

Older children and adults can get a hydrocele due to an injury to the scrotum or other health problems. For example, a hydrocele may develop after surgery for varicocele (VAR-ĭ-kō-sēl), enlarged veins of the spermatic cord that can cause scrotal swelling.

Infertility

Nearly 1 in 7 couples is infertile, which means they haven’t been able to conceive a child even though they’ve had frequent, unprotected sexual intercourse for a year or longer. In up to half of these couples, male infertility plays a role. Male infertility can be caused by low sperm production, abnormal sperm function, or blockages that prevent the delivery of sperm. Illnesses, injuries, chronic health problems, lifestyle choices, and other factors may contribute to male infertility.[21]

For a male to cause pregnancy, the following processes must occur[22]:

- Healthy sperm are produced. At least one testicle must be functioning, and the body must produce testosterone and other hormones to trigger and maintain sperm production.

- Sperm must be carried into the semen. After sperm are produced in the testicles, tubes transport them until they mix with semen and are ejaculated out of the penis.

- There must be enough sperm in the semen. If the number of sperm in the semen (referred to as sperm count) is low, it decreases the odds that one sperm will fertilize a partner’s egg. A low sperm count is fewer than 15 million sperm per milliliter of semen or fewer than 39 million per ejaculate. Aspermia (ā-SPUR-mē-ă) refers to failure to produce sperm.

- Sperm must be functional and able to move. If the movement (referred to as motility) or the function of sperm is abnormal, the sperm may not be able to reach or penetrate the partner’s egg.

There are several possible causes of male infertility. If a couple is not able to conceive within one year of having unprotected sex, the couple can visit fertility specialists for diagnostic testing and infertility treatment.

Prostatitis

Prostatitis (pros-tă-TĪT-ĭs) refers to inflammation of the prostate gland and sometimes areas surrounding it. Prostatitis can be acute or chronic, and some types are caused by a bacterial infection. Symptoms of acute bacterial prostatitis are typically severe and come on suddenly, whereas chronic prostatitis develops slowly and lasts three or more months. Symptoms may include the following[23]:

- Urinary frequency

- Urinary urgency

- A weak or an interrupted urine stream

- Dysuria

- Fever and/or chills

- Painful ejaculation

- Pain in the penis or testicles

A health care provider diagnoses prostatitis by performing diagnostic tests, such as a urinalysis and cystoscopy. Treatment depends upon the cause and may include antibiotics and pain relievers.

Sexually Transmitted Infections

Sexually transmitted infections affect both males and females. The terms sexually transmitted infection (SEKS-ū-ă-lē trăns-MĬT-ed ĭn-FĔK-shŏn) (STI) and sexually transmitted disease (SEKS-ū-ă-lē trăns-MĬT-ed diz-ĒZ) (STD) are used interchangeably. STI and STD imply the infection was acquired through sexual transmission. Examples of STIs include chlamydia, gonorrhea, human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), human papillomavirus (HPV), and herpes simplex virus. The only way to completely avoid STIs is to not have vaginal, anal, or oral sex. If you are sexually active, the following factors can lower your chances of getting an STI[24]:

- Being in a long-term mutually monogamous relationship with a partner who has been tested and does not have STI

- Correctly using condoms every time you have sex

Chlamydia

Chlamydia (klă-MĬD-ē-ă) is the most common type of bacterial STI. It is caused by a bacteria called Chlamydia trachomatis. Chlamydia is often referred to as a “silent disease” because many people with chlamydia do not have any symptoms and unknowingly pass the infection to their sexual partner(s). Anyone can get chlamydia during oral, vaginal, or anal sex with someone who has chlamydia. A pregnant woman can also pass chlamydia to her baby during childbirth, causing eye infections or pneumonia.[25]

Symptoms may not appear until several weeks after having sex with someone who has chlamydia. Symptoms in women include abnormal vaginal discharge, which may have a strong smell, and a burning sensation when urinating. Symptoms in men include discharge from the penis and a burning sensation when urinating. If untreated, chlamydia in females can lead to pelvic inflammatory disease (PĔL-vĭk ĭn-flă-MĂ-tōr-ē dĭ-ZĒZ) (PID), which can cause permanent damage to the reproductive organs and infertility.[26]

Chlamydia is diagnosed by a health care provider by a urine sample or by using a cotton swab to obtain a specimen that is sent to a lab for analysis. Chlamydia is treated with antibiotics. All sexual partners within the past 60 days should be notified and examined by a health care provider, keeping in mind that not having symptoms does not mean there is no infection. Reinfection is common, so people diagnosed with chlamydia should be retested three months after treatment of the initial infection, regardless of whether they believe that their sexual partners were successfully treated.[27]

Gonorrhea

Gonorrhea (gon-ŏ-RĒ-ă) is a bacterial STI caused by Neisseria gonorrhea. Neisseria gonorrhea infects the mucous membranes of the reproductive tract, including the cervix, uterus, and Fallopian tubes in women, and the urethra in both women and men, causing inflammation and discharge. Neisseria gonorrhea can also infect the mucous membranes of the mouth, throat, eyes, and rectum. Gonorrhea is transmitted through sexual contact with the penis, vagina, mouth, or anus of an infected partner. Ejaculation does not have to occur for gonorrhea to be transmitted or acquired. Gonorrhea can also be spread perinatally from mother to baby during childbirth, which can cause blindness, joint infection, or a life-threatening blood infection in the baby if left untreated.[28]

Many people infected with gonorrhea have no symptoms and can unknowingly pass the infection on to their sexual partner(s). Most women with gonorrhea are asymptomatic. Even when a woman has symptoms, they are often so mild and nonspecific that they are mistaken for a bladder or vaginal infection. The initial symptoms and signs in women include dysuria, increased vaginal discharge, or vaginal bleeding between periods. Women with gonorrhea are at risk of developing serious complications from the infection, such as pelvic inflammatory disease (PID).

When present, signs and symptoms of gonorrhea in men include dysuria (painful urination) or a white, yellow, or green urethral discharge that usually appears 1 to 14 days after infection. Men may also experience testicular or scrotal pain.

Symptoms of rectal gonorrhea infection in both men and women may include discharge, anal itching, soreness, bleeding, or painful bowel movements. Pharyngeal gonorrhea infection may cause a sore throat, but it is usually asymptomatic.[29]

Urogenital gonorrhea can be diagnosed by testing urine, a urethral swab (for men), or endocervical or vaginal swab (for women) using nucleic acid amplification testing (no͞o-klē-ĭk ĂS-ĭd ăm-plĭ-fĭ-KĀ-shŏn tĕst-ing) (NAAT). It can also be diagnosed using gonorrhea culture, which requires endocervical or urethral swab specimens.[30]

Gonorrhea is treated with an intramuscular (IM) injection of antibiotics. It is important that individuals complete the treatment and abstain from unprotected sexual activity for at least seven days following treatment. All sexual partners within the past 60 days should be notified and examined, keeping in mind that having no symptoms does not mean there is no infection. Reinfection is common, so people with gonorrhea should be retested three months after treatment of the initial infection, regardless of whether they believe that their sexual partners were successfully treated.[31]

Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV)

Human immunodeficiency virus (hu-man im-yŭ-nō-dĕ-FISH-ĕn-sē VĪ-rŭs) (HIV) is a virus that attacks the T-helper cells (a type of lymphocyte or white blood cell) of the immune system. If HIV is not treated, it can lead to acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (ă-KWĪRD im-yū-nō-dĕ-FISH-ĕn-sē SĬN-drōm) (AIDS). There is currently no cure for HIV, so people who become infected with HIV have it for life. However, with proper medical care, HIV can be controlled, and people with HIV can live long, healthy lives while also preventing its spread to their partners.[32]

Most people infected with HIV have flu-like symptoms within two to four weeks after becoming infected. Symptoms include fever, night sweats, fatigue, swollen lymph nodes, sore throat, muscle aches, and rash. If not treated, the infection becomes chronic, with or without symptoms, and can take up to ten years to develop AIDS. Without HIV treatment, people with AIDS typically only survive about three years.[33]

HIV tests can be performed on blood or oral fluid. HIV is treated with medication called antiretroviral therapy (ăn-tē-rĕ-trō-VĪ-răl THĔR-ă-pē) that reduces the amount of virus in the body, helps maintain a healthy immune system, and prevents AIDS from developing.[34]

Herpes Simplex Virus

Genital herpes (JEN-ĭt-ăl HĔRP-ēz) is an STI caused by the herpes simplex virus (HUR-pēz SĬM-pleks VĪ-rŭs) (HSV) that is characterized by blisters in the genital area. There are two types of herpes simplex viruses: HSV-1 and HSV-2. HSV-1 (oral herpes) causes mouth ulcers, commonly called “cold sores.” HSV-2 causes genital herpes when a person has genital contact with someone who has a genital HSV-2 infection. Additionally, a genital HSV-1 infection can occur when a person receives oral sex from a person with an HSV-1 oral ulcer. Herpes infection can also be passed from mother to child during pregnancy or childbirth, which can result in a potentially fatal neonatal herpes infection.[35]

Herpes lesions typically appear as one or more vesicles (i.e., small blisters), on or around the genitals, rectum, or mouth. The vesicles break and leave painful ulcers that may take two to four weeks to heal after the initial herpes infection. Once a patient is infected with HSV, the virus remains in their body even after the symptoms are gone and can cause recurring outbreaks related to fever, stress, or other triggering factors.[36] See Figure 6.5[37] for an image of a mouth ulcer caused by HSV-1. Although this is not considered an STI, herpes lesions that occur on the genitals have a similar appearance.

HSV nucleic acid amplification tests (NAAT) are the best test for diagnosing herpes, but in some settings, a viral culture is the only test available. There is no cure for herpes. Antiviral medications can shorten outbreaks, and daily suppressive therapy can prevent outbreaks and transmission of the infection to partners.[38]

Human Papillomavirus

Human papillomavirus (hu-man PAP-ĭ-LŌ-mă-VĪ-rŭs) (HPV) is a common STI. Almost three quarters of sexually active individuals have been exposed to HPV during their lifetime. HPV spreads through sexual activity and skin-to-skin contact in the genital area with an infected person. Because some types of HPV are asymptomatic, people don’t know they have the virus and, consequently, pass the virus to their sexual partners.[39]

There are over 100 strains of HPV, and some strains of HPV can cause visible genital warts. Genital warts usually appear as a small bump or group of bumps in the genital area. They can be small or large, raised or flat, or shaped like a cauliflower. Some strains of HPV cause genital, anal, throat, and cervical cancers. For this reason, routine PAP smears for women can help prevent cervical cancer from HPV.[40]

Treatments are available for genital warts, but there is no cure for HPV. The HPV vaccine can protect against diseases (including cancers) caused by HPV. The HPV vaccine is recommended for all preteens (including boys and girls) at age 11 or 12 years and through age 26 years. Most sexually active adults have already been exposed to HPV, so vaccination is not recommended. People who are in a long-term, mutually monogamous relationship are not likely to get a new HPV infection.[41]

Syphilis

Syphilis (SIF-ĭ-lĭs) is an STI that can cause serious health problems without treatment. Infection develops in stages called primary, secondary, latent, and tertiary. Each stage can have different signs and symptoms. Syphilis is spread by direct contact with a syphilis sore during vaginal, anal, or oral sex. Syphilis can also be spread from a mother with syphilis to her unborn baby.[42]

During the first (primary) stage of syphilis, a single sore or multiple sores appear in the location where syphilis entered the body. See Figure 6.6[43] for an image of a sore caused by syphilis, referred to as a chancre. Sores are typically firm, round, and painless. The sore usually lasts three to six weeks and heals regardless of whether treatment is received.

During the secondary stage, skin rashes and/or sores in the mouth, vagina, or anus appear. The rash can show up when the primary sore is healing or several weeks after the sore has healed. The rash can also be on the palms of the hands and/or the bottoms of the feet and look rough, red, or reddish-brown. Without treatment, syphilis can spread to the brain and nervous system (neurosyphilis), the eye (ocular syphilis), or the ear (otosyphilis). This can happen during any of the stages. Syphilis is treated with antibiotics, but antibiotics do not reverse any damages that occurred prior to treatment.[44]

Trichomoniasis

Trichomoniasis (trĭk-ō-mō-NĪ-ă-sĭs) is a common STI caused by infection with Trichomonas vaginalis, a protozoan (tiny, single-celled) parasite. Although symptoms vary, most people who have trichomoniasis cannot tell they have it. Men with trichomoniasis may notice itching or irritation inside the penis, burning after urinating or ejaculating, or discharge from the penis. Women with trichomoniasis may notice itching; burning; redness or soreness of the genitals; dysuria; or a clear, white, yellowish, or greenish vaginal discharge with a fishy smell. Trichomoniasis is diagnosed with a swab specimen evaluated in a laboratory. It is treated with antibiotics taken by mouth.[45]

Spermatocele

A spermatocele (spĕr-MĂT-ō-sēl) is an abnormal sac (cyst) that develops in the epididymis, the small, coiled tube located on the upper testicle that collects and transports sperm. The cause of spermatoceles is unknown but could be due to a blockage in one of the tubes that transport sperm. If a spermatocele grows large enough to cause discomfort, surgery may be required.[46]

Testicular Torsion

Testicular torsion (tĕs-TĬK-ū-lăr TOR-shŏn) occurs when a testicle rotates, twisting the spermatic cord that brings blood to the scrotum. The reduced blood flow causes sudden, severe pain and swelling. Testicular torsion commonly occurs between ages 12 and 18 and usually requires emergency surgery. If treated quickly, the testicle can usually be saved. But when blood flow has been cut off for too long, a testicle might become so badly damaged that it has to be removed.[47]

- “Benign_Prostatic_Hyperplasia_nci-vol-7137-300.jpg” by unknown author for National Cancer Institute is licensed in the Public Domain. ↵

- MedlinePlus [Internet]. Bethesda (MD): National Library of Medicine (US); [updated 2022, Aug. 17]. Enlarged prostate (BPH); [cited 2023, Oct. 10]. https://medlineplus.gov/enlargedprostatebph.html ↵

- MedlinePlus [Internet]. Bethesda (MD): National Library of Medicine (US); [updated 2022, Aug. 17]. Enlarged prostate (BPH); [cited 2023, Oct. 10]. https://medlineplus.gov/enlargedprostatebph.html ↵

- MedlinePlus [Internet]. Bethesda (MD): National Library of Medicine (US); [updated 2022, Aug. 17]. Enlarged prostate (BPH); [cited 2023, Oct. 10]. https://medlineplus.gov/enlargedprostatebph.html ↵

- National Cancer Institute. (2023, February 16). Prostate cancer treatment (PDQ) - patient version. National Institutes of Health. https://www.cancer.gov/types/prostate/patient/prostate-treatment-pdq ↵

- National Cancer Institute. (2023, February 16). Prostate cancer treatment (PDQ) - patient version. National Institutes of Health. https://www.cancer.gov/types/prostate/patient/prostate-treatment-pdq ↵

- National Cancer Institute. (2023, February 16). Prostate cancer treatment (PDQ) - patient version. National Institutes of Health. https://www.cancer.gov/types/prostate/patient/prostate-treatment-pdq ↵

- National Cancer Institute. (2023, February 16). Prostate cancer treatment (PDQ) - patient version. National Institutes of Health. https://www.cancer.gov/types/prostate/patient/prostate-treatment-pdq ↵

- National Cancer Institute. (2023, February 16). Prostate cancer treatment (PDQ) - patient version. National Institutes of Health. https://www.cancer.gov/types/prostate/patient/prostate-treatment-pdq ↵

- National Cancer Institute. (2023, February 16). Prostate cancer treatment (PDQ) - patient version. National Institutes of Health. https://www.cancer.gov/types/prostate/patient/prostate-treatment-pdq ↵

- National Cancer Institute. (2023, February 16). Prostate cancer treatment (PDQ) - patient version. National Institutes of Health. https://www.cancer.gov/types/prostate/patient/prostate-treatment-pdq ↵

- National Cancer Institute. (2023, February 16). Prostate cancer treatment (PDQ) - patient version. National Institutes of Health. https://www.cancer.gov/types/prostate/patient/prostate-treatment-pdq ↵

- National Cancer Institute. (2023, February 16). Prostate cancer treatment (PDQ) - patient version. National Institutes of Health. https://www.cancer.gov/types/prostate/patient/prostate-treatment-pdq ↵

- National Cancer Institute. (2023, February 16). Prostate cancer treatment (PDQ) - patient version. National Institutes of Health. https://www.cancer.gov/types/prostate/patient/prostate-treatment-pdq ↵

- National Cancer Institute. (2023, February 16). Prostate cancer treatment (PDQ) - patient version. National Institutes of Health. https://www.cancer.gov/types/prostate/patient/prostate-treatment-pdq ↵

- National Cancer Institute. (2023, February 16). Prostate cancer treatment (PDQ) - patient version. National Institutes of Health. https://www.cancer.gov/types/prostate/patient/prostate-treatment-pdq ↵

- National Cancer Institute. (2023, February 16). Prostate cancer treatment (PDQ) - patient version. National Institutes of Health. https://www.cancer.gov/types/prostate/patient/prostate-treatment-pdq ↵

- National Cancer Institute. (2023, May 17). Testicular cancer treatment (PDQ) - patient version. National Institutes of Health. https://www.cancer.gov/types/testicular/patient/testicular-treatment-pdq ↵

- National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases. (2017, July). Definitions & facts for erectile dysfunction. National Institutes of Health. https://www.niddk.nih.gov/health-information/urologic-diseases/erectile-dysfunction/definition-facts ↵

- Mayo Clinic. (2023, January 12). Hydrocele. https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/hydrocele/symptoms-causes/syc-20363969 ↵

- Mayo Clinic. (2022, December 28). Male infertility. https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/male-infertility/symptoms-causes/syc-20374773 ↵

- Mayo Clinic. (2022, December 28). Male infertility. https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/male-infertility/symptoms-causes/syc-20374773 ↵

- Mayo Clinic. (2022, February 19). Prostatitis. https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/male-infertility/symptoms-causes/syc-20374773 ↵

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2022, April 12). Chlamydia - CDC basic fact sheet. U.S. Department of Health & Human Services. https://www.cdc.gov/std/chlamydia/stdfact-chlamydia.htm ↵

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2022, April 12). Chlamydia - CDC basic fact sheet. U.S. Department of Health & Human Services. https://www.cdc.gov/std/chlamydia/stdfact-chlamydia.htm ↵

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2022, April 12). Chlamydia - CDC basic fact sheet. U.S. Department of Health & Human Services. https://www.cdc.gov/std/chlamydia/stdfact-chlamydia.htm ↵

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2022, April 12). Chlamydia - CDC basic fact sheet. U.S. Department of Health & Human Services. https://www.cdc.gov/std/chlamydia/stdfact-chlamydia.htm ↵

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2023, April 11). Gonorrhea - CDC detailed fact sheet. U.S. Department of Health & Human Services. https://www.cdc.gov/std/gonorrhea/stdfact-gonorrhea-detailed.htm ↵

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2023, April 11). Gonorrhea - CDC detailed fact sheet. U.S. Department of Health & Human Services. https://www.cdc.gov/std/gonorrhea/stdfact-gonorrhea-detailed.htm ↵

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2023, April 11). Gonorrhea - CDC detailed fact sheet. U.S. Department of Health & Human Services. https://www.cdc.gov/std/gonorrhea/stdfact-gonorrhea-detailed.htm ↵

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2023, April 11). Gonorrhea - CDC detailed fact sheet. U.S. Department of Health & Human Services. https://www.cdc.gov/std/gonorrhea/stdfact-gonorrhea-detailed.htm ↵

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2022, June 30). What is HIV? U.S. Department of Health & Human Services. https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/basics/whatishiv.html ↵

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2022, June 30). What is HIV? U.S. Department of Health & Human Services. https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/basics/whatishiv.html ↵

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2022, June 30). What is HIV? U.S. Department of Health & Human Services. https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/basics/whatishiv.html ↵

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2021, July 22). Genital herpes - CDC detailed fact sheet. U.S. Department of Health & Human Services. https://www.cdc.gov/std/herpes/stdfact-herpes-detailed.htm ↵

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2021, July 22). Genital herpes - CDC detailed fact sheet. U.S. Department of Health & Human Services. https://www.cdc.gov/std/herpes/stdfact-herpes-detailed.htm ↵

- “Herpes(PHIL_1573_lores).jpg” by Centers for Disease Control and Prevention is licensed in the Public Domain. ↵

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2021, July 22). Genital herpes - CDC detailed fact sheet. U.S. Department of Health & Human Services. https://www.cdc.gov/std/herpes/stdfact-herpes-detailed.htm ↵

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2022, April 12). Genital HPV infection - basic fact sheet. U.S. Department of Health & Human Services. https://www.cdc.gov/std/hpv/stdfact-hpv.htm ↵

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2022, April 12). Genital HPV infection - basic fact sheet. U.S. Department of Health & Human Services. https://www.cdc.gov/std/hpv/stdfact-hpv.htm ↵

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2022, April 12). Genital HPV infection - basic fact sheet. U.S. Department of Health & Human Services. https://www.cdc.gov/std/hpv/stdfact-hpv.htm ↵

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2022, February 10). Syphilis - CDC basic fact sheet. U.S. Department of Health & Human Services. https://www.cdc.gov/std/syphilis/stdfact-syphilis.htm ↵

- “Extragenital_syphilitic_chancre_of_the_left_index_finger_PHIL_4147_lores.jpg” by Centers for Disease Control and Prevention is licensed in the Public Domain. ↵

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2022, February 10). Syphilis - CDC basic fact sheet. U.S. Department of Health & Human Services. https://www.cdc.gov/std/syphilis/stdfact-syphilis.htm ↵

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2022, April 25). Trichomoniasis - CDC basic fact sheet. U.S. Department of Health & Human Services. https://www.cdc.gov/std/trichomonas/stdfact-trichomoniasis.htm ↵

- Mayo Clinic. (2022, March 31). Spermatocele. https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/spermatocele/symptoms-causes/syc-20377829 ↵

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2022, February 24). Trichomoniasis - CDC basic fact sheet. U.S. Department of Health & Human Services. https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/testicular-torsion/symptoms-causes/syc-20378270 ↵