3.4 Anatomy and Physiology of the Integumentary System

This section will provide a general overview of the anatomy and physiology of the integumentary system.

Anatomy of the Integumentary System

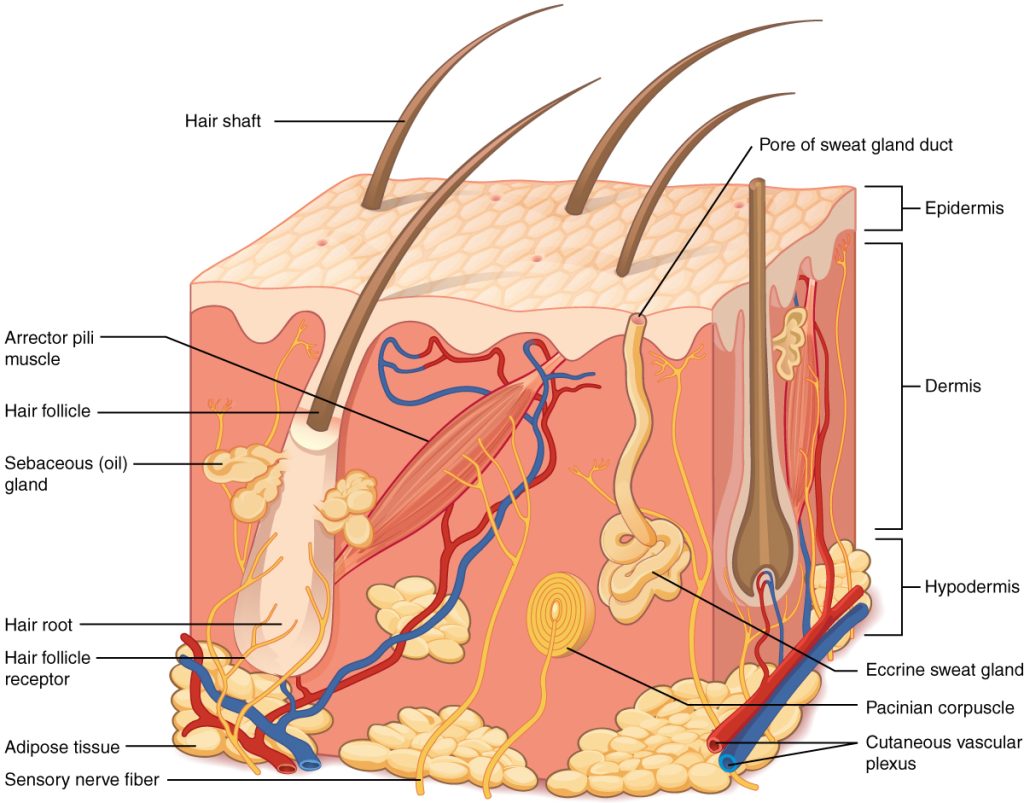

The skin and its accessory structures make up the integumentary system, which provides the body with overall protection. The skin is made of multiple layers of cells and tissues, which are held to underlying structures by connective tissue. The skin is composed of three main layers: the epidermis, dermis, and hypodermis.[1] See Figure 3.1[2] for an illustration of the three main layers of the skin and other anatomical structures.

The epidermis (ĕp-ī-DUR-mĭs) is the outermost layer of skin. It is composed of keratinized epithelium. Keratin (kĕr-ă-TIN) is an intracellular fibrous protein that gives hair, nails, and skin their hardness and water-resistant properties. The keratinocytes in the epithelium are dead and regularly slough away, being replaced by cells from the deeper layers. Melanocytes (MĔL-ăn-ō-sīts) are melanin-producing cells located in the bottom layer of epidermis. Melanin is a dark pigment primarily responsible for skin color.[3]

The dermis (DĔR-mĭs) lies under the epidermis. It contains blood and lymph vessels, nerves, and other structures, such as hair follicles and sweat glands.

The hypodermis (hī-pō-DUR-mĭs), also referred to as subcutaneous (sub-kū-TĀ-nē-us) tissue, is the layer underneath the dermis. It consists of connective tissue that is vascularized (VĂS-kū-lə-rīzd) (i.e., provided with blood vessels) and adipose (AD-ĭ-pōs) tissue. Adipose tissue serves as fat storage and provides insulation and cushioning. Elastin (ĭ-LĀS-tĭn) is a protein in this connective tissue that makes skin stretchy. The hypodermis connects the skin to the underlying bones and muscles, referred to as the fascia (FASH-ē-ă). The underlying hypodermis has important roles in storing fats, forming a “cushion” over underlying structures and providing insulation from cold temperatures.[4]

Accessory Structures

Accessory structures of the skin include hair, nails, sweat glands, and sebaceous glands.

Hair

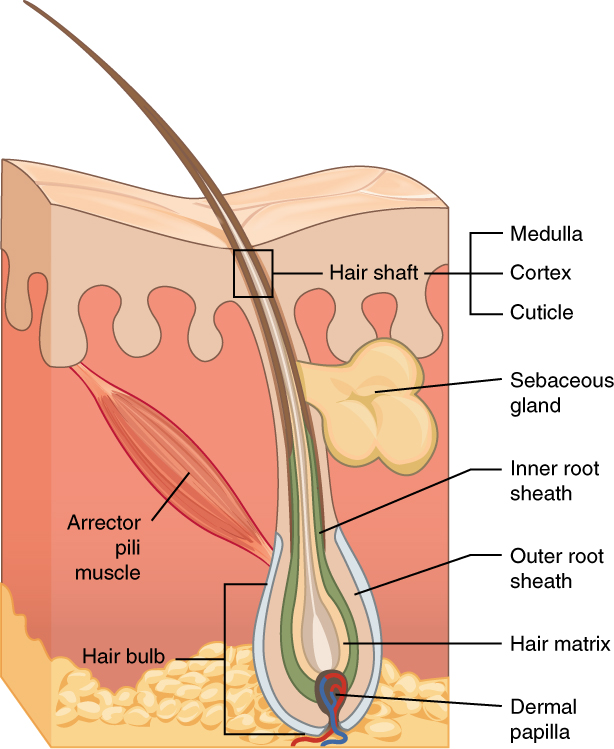

Hair is a keratinous filament growing out of the epidermis. It is primarily made of dead, keratinized cells. Strands of hair originate in the dermis in a structure called the hair follicle. The hair shaft is the part of the hair not anchored to the follicle, and much of this is exposed at the skin’s surface. The rest of the hair, which is anchored in the follicle, lies below the surface of the skin and is referred to as the hair root.[5]

Each hair root is connected to a smooth muscle called the arrector pili that contracts in response to nerve signals from the sympathetic nervous system (sĭm-pă-THĔT-ĭk NĔR-vŭs SIS-tĕm). These signals make the external hair shaft “stand up,” commonly referred to as “goose bumps.” The primary purpose for this response is to trap a layer of air to add insulation and warmth.[6] See Figure 3.2[7] for an illustration of hair.

Hair serves a variety of functions, including protection, sensory input, thermoregulation, and communication. For example, hair in the nose and ears and around the eyes (eyelashes) defends the body by trapping and excluding dust particles that may contain allergens and microbes.[8]

Hair grows and is eventually shed and replaced by new hair. Hair loss occurs if there is more hair shed than what is replaced and can happen due to hormonal or dietary changes. Hair loss can also result from the aging process or the influence of hormones. Alopecia (ăl-ō-PĒ-shē-ă) is the medical term for hair loss in areas where hair normally grows. Conversely, hirsutism (HUR-sū-tĭz-əm) is the medical term for excessive hair growth in areas where hair is usually minimal or absent.

Similar to the skin, hair gets its color from the pigment melanin, and different hair color results from differences in the type of melanin. As a person ages, the melanin production decreases, and hair tends to lose its color and becomes gray and/or white.[9]

Dandruff (DĂN-drŭf) refers to flakes of dead skin from the scalp.

Nails

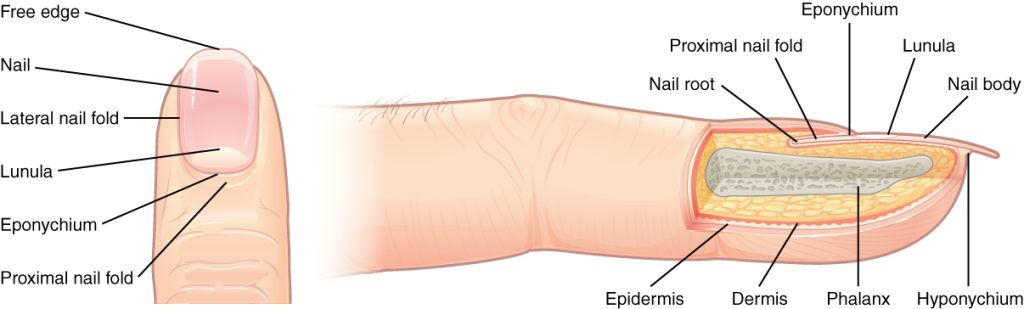

The nail bed is a specialized structure of the epidermis that is found at the tips of the fingers and toes. The nail body is formed on the nail bed and protects the tips of our fingers and toes as they are the farthest extremities and the parts of the body that experience the maximum mechanical stress. The term cuticle (KYŪ-tĭ-kĭl) refers to the protective layer of skin at the base of a nail.[10] See Figure 3.3[11] for an illustration of nails.

The nail body is composed of densely packed dead keratinocytes. The nail body forms a back support for picking up small objects with the fingers. The nail bed is rich in blood vessels, making it appear pink, except at the base, where a thick layer of epithelium over the nail matrix forms a crescent-shaped region called the lunula.[12]

Onycholysis (ŏn-ĭ-KOL-ĭ-sĭs) refers to the separation of a fingernail or toenail from its nail bed. Onychophagia (ŏn-ĭ-KOF-ă-jē-ă) refers to the habit of biting one’s nails.

Sweat Glands

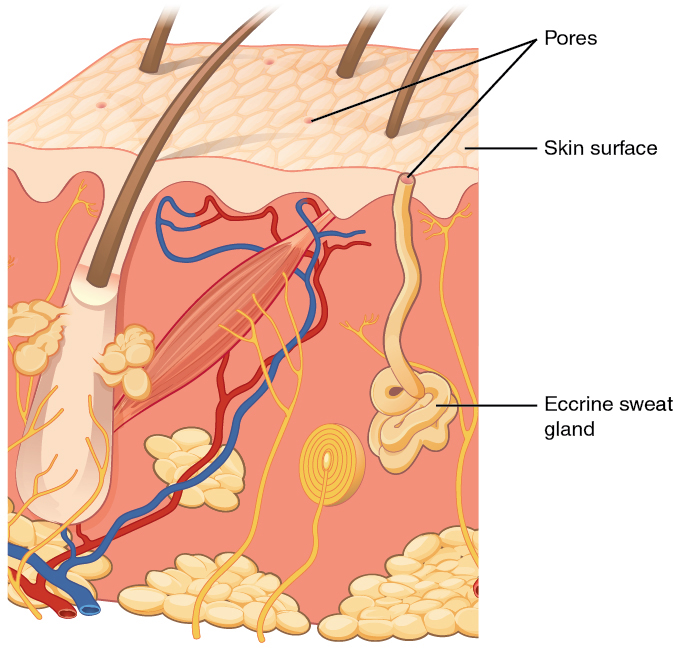

When the body becomes warm, sweat glands produce sweat to cool the body. There are two types of sweat glands called eccrine sweat glands and apocrine sweat glands, each secreting slightly different products.

An eccrine sweat gland (ĔK-rĭn swĕt glănd) is type of gland that produces sweat for thermoregulation, as previously described in this section. These glands are found all over the skin’s surface but are especially abundant on the palms of the hand, the soles of the feet, and the forehead. This type of sweat is composed mostly of water and some salt.[13] See Figure 3.4[14] for an illustration of an eccrine sweat gland.

Apocrine sweat glands (AP-ŏ-krĕn swĕt glănds) are found in hair follicles in densely hairy areas, such as the armpits and genital regions. In addition to water and salt, apocrine sweat glands release organic compounds that make the sweat thicker and subject to bacterial decomposition, resulting in odor. The release of apocrine sweat is controlled by hormones and the nervous system. Most commercial antiperspirants use an aluminum-based compound as their primary active ingredient to stop sweat. When the antiperspirant enters the sweat gland duct, the aluminum-based compounds physically block the duct and prevent sweat from coming out of the pore.[15]

Anhidrosis (ăn-hī-DRŌ-sĭs) is the medical term used for the absence of sweat production. Hyperhidrosis (hī-pĕr-hī-DRŌ-sĭs) is the medical term used for excessive sweating.

Sebaceous Glands

A sebaceous gland (sē-BĀ-shŭs glănd) is a type of oil gland that lubricates and waterproofs the skin and hair. Most sebaceous glands are associated with hair follicles. They generate and excrete sebum, a mixture of lipids, onto the skin surface, thereby naturally lubricating the dry and dead layer of keratinized cells. The fatty acids of sebum also have antibacterial properties and prevent water loss from the skin in low humidity environments. The secretion of sebum is stimulated by hormones, many of which do not become active until puberty. Thus, sebaceous glands are relatively inactive during childhood.[16]

Physiology of the Integumentary System

The skin and accessory structures perform a variety of these essential functions[17]:

- Protecting the body from invasion by microorganisms, chemicals, and other environmental factors

- Acting as a sensory organ

- Modulating body temperature and electrolyte balance

- Synthesizing vitamin D

Protection

The skin protects the body from wind, water, and ultraviolet (UV) light. It acts as a protective barrier against excessive water loss referred to as dehydration (dē-hī-DRĀ-shŏn). It is also the first line of defense against abrasive activity such as grit, microbes, or harmful chemicals. Sweat excreted from sweat glands also deters microbes from overcolonizing the skin surface.[18]

Sensory Function

The epidermis, dermis, and the hypodermis contain specialized sensory nerve structures that detect touch, surface temperature, and pain. These receptors are concentrated on the tips of the fingers, which are very sensitive to touch.[19]

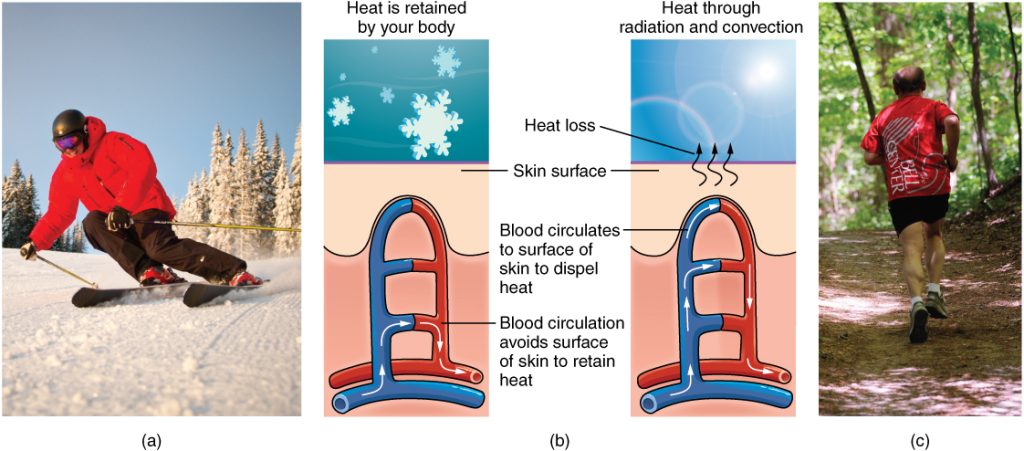

Thermoregulation

The integumentary system helps regulate body temperature in association with the sympathetic nervous system. The sympathetic nervous system is continuously monitoring body temperature and initiating appropriate motor responses.[20]

When the body becomes excessively warm, sweat glands secrete water, salt, and other substances to cool the body. Even when the body does not appear to be noticeably sweating, approximately 500 mL of sweat are secreted a day. This amount can greatly vary depending on the person’s metabolic rate, physical activity, heat exposure, and medical condition. When the sweat evaporates from the skin surface, the body is cooled as body heat is dissipated. In addition to sweating, small blood vessels called arterioles in the dermis dilate so that excess heat carried by the blood can dissipate through the skin and into the surrounding environment.[21]

When body temperatures drop, the arterioles constrict to minimize heat loss, particularly in the ends of the fingers and toes and the tip of the nose. This constriction reduces blood flow to the skin to prevent the loss of heat and keep the internal organs warm. It can cause the skin to take on a whitish hue. If the temperature of the skin drops too much (such as in environmental temperatures below freezing), the conservation of body core heat can result in frostbite (FROST-bīt).[22] See Figure 3.5[23] for illustrations demonstrating thermoregulation.

Medical conditions can cause excessive, profuse sweating referred to as diaphoresis (dī-ă-fŏ-RĒ-sĭs). For example, a significant symptom of a heart attack, in addition to chest pain, is diaphoresis.

Vitamin D Synthesis

The epidermal layer synthesizes vitamin D when exposed to UV light. Vitamin D is essential for normal absorption of calcium and phosphorous, which are required for healthy bones. In addition to its essential role in bone health, vitamin D is essential for general immunity against bacterial, viral, and fungal infections. Significant absence of sun exposure can lead to a lack of vitamin D in the body called rickets (RIK-ĕts). For this reason, vitamin D is added as a supplement to many foods, including milk and orange juice.[24]

Changes in the Integumentary System Due to Aging

All body systems change as a person ages. In the skin, older adults develop a thinner epidermis. Additionally, the dermis, responsible for the elasticity and resilience of the skin, exhibits a reduced ability to regenerate, which leads to slower wound healing. The hypodermis, with its fat stores, loses structure due to the reduction and redistribution of fat, which, in turn, contributes to the thinning and sagging of skin.[25] See Figure 3.6[26] for an illustration of these signs of aging skin.

The accessory structures also have lowered activity, generating thinner hair and nails and reduced amounts of sebum and sweat. A reduced sweating ability creates a risk for older adults in extreme heat. Other cells in the skin, such as melanocytes and dendritic cells, also become less active, leading to a paler skin tone and lowered immunity.[27]

View the following supplementary YouTube video[28] to review the anatomy and physiology of the integumentary system: The Integumentary System, Part 2 – Skin Deeper: Crash Course A&P #7

- This work is a derivative of Anatomy and Physiology by OpenStax licensed under CC BY 4.0. Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/anatomy-and-physiology/pages/1-introduction ↵

- “501_Structure_of_the_skin.jpg” by J. Gordon Betts, et al., for OpenStax is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- This work is a derivative of Anatomy and Physiology by OpenStax licensed under CC BY 4.0. Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/anatomy-and-physiology/pages/1-introduction ↵

- This work is a derivative of Anatomy and Physiology by OpenStax licensed under CC BY 4.0. Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/anatomy-and-physiology/pages/1-introduction ↵

- This work is a derivative of Anatomy and Physiology by OpenStax licensed under CC BY 4.0. Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/anatomy-and-physiology/pages/1-introduction ↵

- This work is a derivative of Anatomy and Physiology by OpenStax licensed under CC BY 4.0. Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/anatomy-and-physiology/pages/1-introduction ↵

- “506_Hair.jpg” by OpenStax is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- This work is a derivative of Anatomy and Physiology by OpenStax licensed under CC BY 4.0. Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/anatomy-and-physiology/pages/1-introduction ↵

- This work is a derivative of Anatomy and Physiology by OpenStax licensed under CC BY 4.0. Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/anatomy-and-physiology/pages/1-introduction ↵

- This work is a derivative of Anatomy and Physiology by OpenStax licensed under CC BY 4.0. Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/anatomy-and-physiology/pages/1-introduction ↵

- “507_Nails.jpg” by OpenStax is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- This work is a derivative of Anatomy and Physiology by OpenStax licensed under CC BY 4.0. Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/anatomy-and-physiology/pages/1-introduction ↵

- This work is a derivative of Anatomy and Physiology by OpenStax licensed under CC BY 4.0. Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/anatomy-and-physiology/pages/1-introduction ↵

- “508_Eccrine_gland.jpg” by OpenStax is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- This work is a derivative of Anatomy and Physiology by OpenStax licensed under CC BY 4.0. Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/anatomy-and-physiology/pages/1-introduction ↵

- This work is a derivative of Anatomy and Physiology by OpenStax licensed under CC BY 4.0. Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/anatomy-and-physiology/pages/1-introduction ↵

- This work is a derivative of Anatomy and Physiology by OpenStax licensed under CC BY 4.0. Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/anatomy-and-physiology/pages/1-introduction ↵

- This work is a derivative of Anatomy and Physiology by OpenStax licensed under CC BY 4.0. Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/anatomy-and-physiology/pages/1-introduction ↵

- This work is a derivative of Anatomy and Physiology by OpenStax licensed under CC BY 4.0. Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/anatomy-and-physiology/pages/1-introduction ↵

- This work is a derivative of Anatomy and Physiology by OpenStax licensed under CC BY 4.0. Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/anatomy-and-physiology/pages/1-introduction ↵

- This work is a derivative of Anatomy and Physiology by OpenStax licensed under CC BY 4.0. Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/anatomy-and-physiology/pages/1-introduction ↵

- This work is a derivative of Anatomy and Physiology by OpenStax licensed under CC BY 4.0. Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/anatomy-and-physiology/pages/1-introduction ↵

- “515_Thermoregulation.jpg” by OpenStax is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- This work is a derivative of Anatomy and Physiology by OpenStax licensed under CC BY 4.0. Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/anatomy-and-physiology/pages/1-introduction ↵

- This work is a derivative of Anatomy and Physiology by OpenStax licensed under CC BY 4.0. Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/anatomy-and-physiology/pages/1-introduction ↵

- “516_Aging.jpg” by OpenStax is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- This work is a derivative of Anatomy and Physiology by OpenStax licensed under CC BY 4.0. Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/anatomy-and-physiology/pages/1-introduction ↵

- CrashCourse. (2015, February 16). The integumentary system, Part 2 - Skin deeper: Crash Course Anatomy & Physiology #7 [Video]. YouTube. All rights reserved. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=EN-x-zXXVwQ ↵