13.7 Medical Specialists, Diagnostic Testing, and Procedures Related to the Skeletal System

Medical Specialists

Orthopedists and Orthopedic Surgeons

Orthopedics (or-thŏ-pē-dĭks) is a branch of medicine that treats disorders and diseases related to the musculoskeletal system. Orthopedists (or-thŏ-pē-dĭsts) are medical doctors who specialize in the prevention, diagnosis, treatment, and surgery of disorders and diseases related to the musculoskeletal system. Some orthopedists are generalists, whereas others specialize in certain areas of the body, such as the hip and knee, foot and ankle, shoulder and elbow, hand, or spine. Orthopedic surgeons perform surgery to repair a musculoskeletal injury or condition. They treat patients of all ages, from newborns to the elderly, and treat conditions such as fractures, sports injuries, joint replacements, and spinal deformities.[1]

For more details about orthopedists, see the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons’ web page.

Rheumatologist

Rheumatology (rū-mă-tŏl-ŏ-jē) is the study of inflammatory or infectious conditions of the joints and other parts of the musculoskeletal system. Rheumatologists (rū-mă-tŏl-ŏ-jĭsts) are physicians who specialize in the diagnosis and treatment of musculoskeletal diseases and systemic autoimmune conditions, commonly referred to as rheumatic diseases. These diseases, such as rheumatoid arthritis, can potentially cause joint deformities.

For more information, see the American College of Rheumatology’s web page called “What is a Rheumatologist?”

Doctor of Osteopathy

Osteopathy (ŏs-tē-OP-ă-thē) is a branch of medical practice that emphasizes the treatment of medical disorders through the manipulation and massage of the bones, joints, and muscles. A Doctor of Osteopathic Medicine (dŏk-tŏr ŏf ŏs-tē-ŏ-PĂTH-ĭk mĕd-ĭ-sĭn) (DO) uses a whole-person approach to help prevent illness and injury. DOs look beyond symptoms to understand how lifestyle and environmental factors impact a person’s well-being. They practice medicine according to science and technology, but also consider options to complement medications and surgery. As part of their education, DOs receive special training in the musculoskeletal system, the body’s interconnected system of nerves, muscles, and bones.[2]

For more information, go to the American Osteopathic Association’s About Us web page.

Radiologist

A radiologist (RĀ-dē-ŏ-jĭst) is a physician who specializes in diagnosing and treating injuries and diseases using medical imaging (radiology) procedures such as X-rays, computed tomography (CT), magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), nuclear medicine, positron emission tomography (PET), and ultrasound. Diagnostic radiologists use a variety of imaging procedures to see inside the body and assess or diagnose the patient’s condition. Interventional radiologists diagnose and treat patients using image-guided, minimally invasive techniques such as X-rays and MRI. They carefully guide instruments through tiny incisions in the body and deliver targeted treatments for conditions such as heart disease, stroke, cancer, and uterine fibroids. Radiation oncologists use radiation therapy to treat cancer.

Read more information about radiologists on the American College of Radiology’s web page What is a Radiologist?

Radiology Technologist

A radiology technologist (rā-dē-ŎL-ŏ-jē tĕk-nŎL-ŏ-jĭst), commonly called an X-ray tech, is a health care professional who is specially trained to perform medical imaging like X-rays, CT scans, MRIs, and PET scans. To become a radiology technologist or MRI technologist, a person completes an associate degree and passes a certification exam.

Read more information about the occupational outlook for radiology technologists on the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics’ Radiologic and MRI Technologists web page.

Diagnostic Testing

Common diagnostic procedures related to the skeletal system are discussed in this section.

X-rays

X-rays (ĕks-rāz) use a form of radiation that travels through the body and strikes an X-ray detector (such as radiographic film or a digital X-ray detector) on the other side of the patient, forming an image that represents the “shadows” of objects inside the body. Bones readily absorb X-rays and, therefore, produce high contrast on the X-ray detector. As a result, bony structures appear whiter than other tissues against the black background of a radiograph. X-rays are used to detect bone fractures, tumors, and dental problems.[3] See Figure 13.30[4] for an image of a normal hip X-ray.

When used appropriately, the diagnostic benefits of X-ray scans significantly outweigh the risks. However, X-rays produce ionizing radiation, a form of radiation that has the potential to harm living tissue. This risk increases with the number of X-ray exposures added up over the lifetime of an individual. However, the risk of developing cancer from radiation exposure is generally small. Children are more sensitive to ionizing radiation and have a long life expectancy, so machine settings can be adjusted according to the patient’s age.[5]

Bone Mineral Density Testing

A bone mineral density (bōn mĭn-ĕr-ăl dĕn-sĭ-tē) is a test that measures calcium and other minerals in bone. Bones can become less dense as people age or if certain medical conditions occur. When too much bone is lost, osteopenia or osteoporosis can develop, causing bones to become weak and brittle and increasing the risk of fractures.[6]

The most common bone mineral density test is a central dual energy X-ray absorptiometry or also called a DEXA scan (DĔK-să skăn). DEXA scans use radiation to measure how much calcium and other minerals are in a specific area of the bone. Because the weakest bones that break most often due to osteoporosis are the hip and spine, DEXA scans typically measure bone mineral density in these bones.[7] See Figure 13.31[8] for an image of a DEXA scan.

Postmenopausal women and men over age 50 receive bone mineral density test results as a “T-score.” A T-score is the difference between their bone mineral density and 0, which represents the bone mineral density of a healthy young adult. The lower the T-score, the higher the risk of bone fracture[9]:

- 1 or higher indicates the bone is healthy

- –1 to –2.5 indicates osteopenia

- –2.5 or lower indicates osteoporosis

Procedures

Arthrocentesis

Arthrocentesis (ar-thrō-sen-TĒ-sĭs) is a surgical puncture to aspirate fluid from a joint, such as the knee. It can help the health care provider find the cause of swollen, painful joints and can also provide symptom relief. After aspiration, the health care provider may inject medications into the joint to temporarily ease pain and inflammation.

View a supplementary YouTube video[10] from Stanford EdTech on arthrocentesis: Arthrocentesis – What to Expect

Arthrodesis

Arthrodesis (ar-THROD-ĕ-sĭs) is the surgical immobilization of a joint by fusion of the adjacent bones. This procedure is performed to relieve unrelenting pain in a joint that cannot be appropriately managed by traditional treatments, physical therapy, splints, or pain medication. It is commonly performed on joints in the foot, ankle, spine, and wrist.[11]

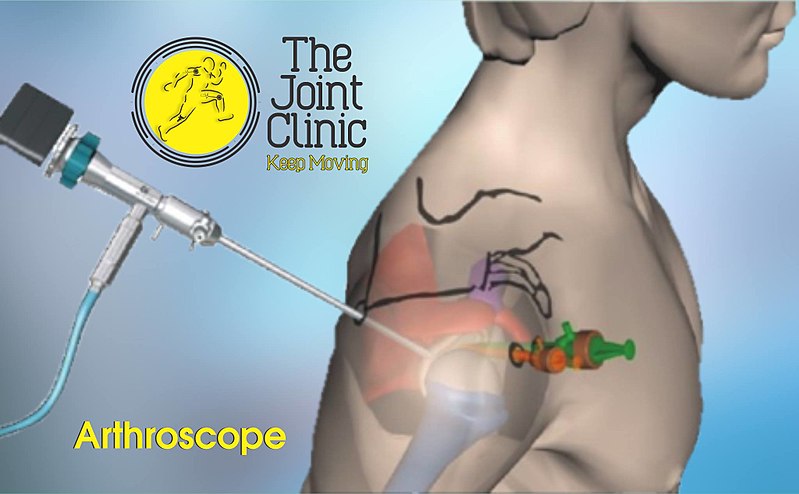

Arthroscopy

Arthroscopy (är-THRŌ-skō-pē) is a common procedure performed by orthopedic surgeons to view the inside of a joint to diagnose and/or to repair joint problems. The patient is given a local anesthetic, and the surgeon inserts an arthroscope through an incision in the skin. Arthroplasty (AR-thrŏ-plas-tē), surgical repair of a joint, may take place during the procedure.[12] See Figure 13.32[13] for an illustration of a shoulder arthroscopy.

Below-the-Knee Amputation

A below-the-knee amputation (bĭ-lō-thē-nē ăm-pyū-TĀ-shŏn (BKA) is performed by an orthopedic surgeon who removes the foot, ankle, part of the tibia, fibula, and corresponding soft tissue structures. It is considered a life-saving procedure for patients who have decreased blood flow and/or infection of the lower extremity. It is typically performed due to trauma, severe peripheral arterial disease, and/or severe infection related to diabetes. After the procedure, the patient receives an artificial body part called a prosthesis (PRŌS-thē-sĭs) and participates in restorative care. Restorative care includes physical therapy and occupational therapy with the goal to achieve optimal functioning and independence in completing daily activities.[14] See Figure 13.33[15] for an image of a man with a leg prosthesis. Read more about physical therapy and occupational therapy in the “Medical Specialists, Diagnostic Testing, and Procedures Related to the Muscular System” in the “Muscular System Terminology” chapter.

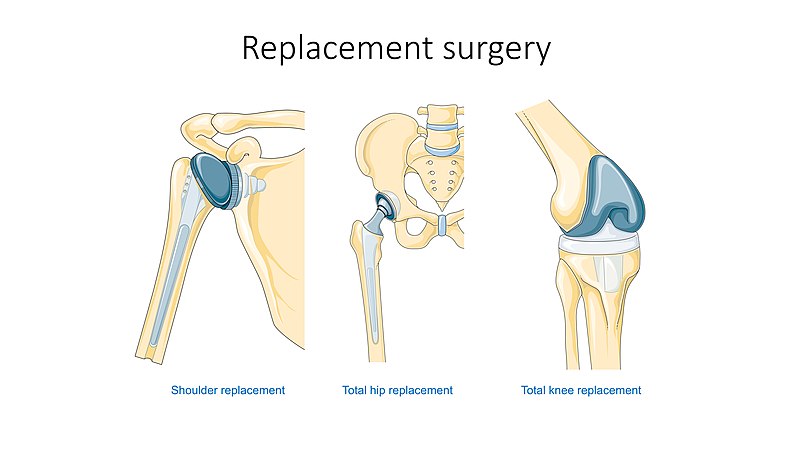

Joint Replacement Surgery

Arthroplasty (ÄR-thrō-plăs-tē) refers to surgical repair or replacement of a joint. Common joint replacement surgeries include hip replacement, knee replacement, and shoulder replacement. See Figure 13.34[16] for an illustration of joint replacement surgeries. During joint replacement surgery, an orthopedic surgeon removes the diseased parts of the joint and replaces them with new, artificial parts that mimic the function of the normal joint.

A total hip replacement (tō-tăl hĭp rē-plās-mĕnt) (THR), also called a total hip arthroplasty (tō-tăl hĭp är-thrŏ-plăs-tē) (THA), refers to replacement of the head of the femur and acetabulum with replacement parts that are either metal, ceramic, or hard plastic. THR may be required due to osteoarthritis, osteonecrosis (when parts of a bone die due to decreased blood supply), or a hip fracture from an injury or fall.[17]

A total knee replacement (tō-tăl nē rē-plās-mĕnt) (TKR), also called total knee arthroplasty (tō-tăl nē är-thrŏ-plăs-tē) (TKA), refers to surgical removal of worn surfaces of the knee joint due to severe osteoarthritis. During the surgery, damaged bone and cartilage are replaced with parts made of metal and plastic.

Open and Closed Reduction and Internal Fixation

Open reduction and internal fixation (ō-pĕn rĭ-DŬK-shŏn ănd ĭn-tĕr-năl fĭk-SĀ-shŏn) (ORIF) is a type of surgery used to stabilize and heal a broken bone. During an open reduction, orthopedic surgeons expose the bone and reposition the pieces of fractured bone, so they are back in their proper alignment and heal correctly. In contrast, during closed reduction surgery, a doctor physically moves the bones back into place without surgically exposing the bone. Internal fixation refers to physically reconnecting the bones using screws, plates, wires, or nails. See Figure 13.35[18] for an X-ray illustration of femur fracture repaired with internal fixation using screws.

- American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons. (n.d.). Orthopaedic surgeons: Restoring mobility and keeping our nation in motion. https://www.aaos.org/about/what-is-an-orthopaedic-surgeon ↵

- American Osteopathic Association. (n.d.). About us. https://osteopathic.org/about/ ↵

- National Institute of Biomedical Imaging and Bioengineering. (2022, June). X-rays. National Institutes of Health. https://www.nibib.nih.gov/science-education/science-topics/x-rays ↵

- “X-ray_of_a_normal_hip.jpg” by Mikael Häggström, M.D. is licensed under CC0, Public Domain ↵

- National Institute of Biomedical Imaging and Bioengineering. (2022, June). X-rays. National Institutes of Health. https://www.nibib.nih.gov/science-education/science-topics/x-rays ↵

- National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases. (2023, May). Bone mineral density tests: What the numbers mean. National Institutes of Health. https://www.niams.nih.gov/health-topics/bone-mineral-density-tests-what-numbers-mean ↵

- National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases. (2023, May). Bone mineral density tests: What the numbers mean. National Institutes of Health. https://www.niams.nih.gov/health-topics/bone-mineral-density-tests-what-numbers-mean ↵

- “4371556142_3aeb50e381_b.jpg” by ActiveSteve is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 2.0 ↵

- National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases. (2023, May). Bone mineral density tests: What the numbers mean. National Institutes of Health. https://www.niams.nih.gov/health-topics/bone-mineral-density-tests-what-numbers-mean ↵

- Stanford EdTech. (2019, April 8). Arthrocentesis - What to expect [Video]. YouTube. All rights reserved. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=onbA5nPYKqU ↵

- This work is a derivative of StatPearls by Jimenez & Anand and is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- Cleveland Clinic. (2021, June 23). Arthrocentesis (joint aspiration). https://my.clevelandclinic.org/health/treatments/14512-arthrocentesis-joint-aspiration ↵

- “Shoulder_Arthroscopy.jpg” by The Joint Clinic is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0 ↵

- This work is a derivative of StatPearls by Adams & Lakra and is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- “pexels-kampus-production-8346699.jpg” by Kampus Production via Pexels, is licensed under CC0 ↵

- “Replacement_surgery_-_Shoulder_total_hip_and_total_knee_replacement_--_Smart-Servier.jpg” by Laboratoires Servier is licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0 ↵

- National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Disease. (2023, August). Hip replacement surgery. National Institutes of Health. https://www.niams.nih.gov/health-topics/hip-replacement-surgery ↵

- “Femur-fractura-nail-artificial-bone.png” by Fry72 Karel Frydrýšek is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0 ↵