11.6 Diseases and Disorders of the Lymphatic and Immune System

Immune system disorders occur when the immune response is directed against normal body tissue or is excessive or deficient. For example, an allergy (AL-ĕr-jē) is an inflammatory response due to a hypersensitivity to a substance that most people’s bodies perceive as harmless. Histamine released during the immune response is a primary cause of allergy and anaphylactic shock symptoms. Autoimmune disease (OT-ō-im-yūn diz-ĒZ) is the inability of the body to distinguish its own cells from foreign invaders, producing antibodies that attack its own tissues. Immunodeficiency (ĭm-yŭ-nō-dĕ-FISH-ĕn-sē) results from a failure or absence of lymphocytes and phagocytes. Immunodeficiencies can be either primary or secondary.[1] These conditions are further discussed in the following subsections.

Hypersensitivity Reactions

The body’s immune responses are essential defense mechanisms designed to protect us against threats, including infections and cancer. However, an individual’s immune system can have an exaggerated immune response triggered by exposure to a specific antigen, referred to as a hypersensitivity (hī-pĕr-sĕn-sĭ-TĬV-ĭ-tē) reaction. This kind of exaggerated reaction can damage normal tissues and cause a range of health issues.[2]

Allergic (AL-ĕr-jĭk) responses are specific types of hypersensitivity reactions that arise when the immune system reacts to allergens. Allergens (AL-ĕr-jĕnz) are substances that are generally harmless to most individuals. Common allergens include pollen, dust mites, pet dander, certain foods, and insect venom. When a person with allergies encounters these allergens, their immune system goes into overdrive, releasing histamines and other inflammatory molecules that trigger symptoms such as itching, sneezing, wheezing, hives, or anaphylaxis.

Anaphylaxis (ăn-ă-fĭ-LĂK-sĭs) is a severe, potentially life-threatening allergic reaction that can cause bronchoconstriction and swelling of the throat, leading to obstruction of the airway, as well as decreased cardiac output that can lead to shock. Recognition of early symptoms and signs of anaphylaxis and prompt intervention are crucial. Treatment typically involves the administration of epinephrine to counteract the systemic effects of anaphylaxis and stabilize the patient’s condition.[3]

See Table 11.6 for a summary of hypersensitivity reactions, examples, and treatments.

Table 11.6. Hypersensitivity Reactions[4]

| Hypersensitivity Type | Description | Mechanism | Examples | Treatments |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Type 1 Hypersensitivity (Immediate) | Rapid and excessive immune responses to harmless antigens (allergens) that lead to allergic reactions. | Upon initial exposure, sensitization occurs with production of IgE antibodies against the allergen. Upon subsequent exposure, the allergen binds to IgE antibodies, triggering the release of inflammatory mediators like histamine. | Inhaled allergens (pollens, animal dander), ingested allergens (foods, drugs), injected allergens (bee venom, drugs), contacted allergens (latex, environmental proteins); anaphylactic reactions can occur. | Antihistamines for allergic symptoms; corticosteroids for severe allergic reactions; epinephrine for anaphylactic reactions. |

| Type 2 Hypersensitivity (Cytotoxic) | Antibodies target antigens on cell surfaces, leading to the destruction or dysfunction of the affected cells. | Antibodies (IgG, IgM) bind to antigens on cell surfaces, triggering immune-mediated destruction through complement activation or antibody-dependent cell-mediated cytotoxicity. | Incompatible blood transfusion reactions and hemolytic disease of newborn (when Rh+ newborns are born to Rh- mothers who have existing antibodies to Rh+ blood). | Administer compatible blood product transfusions and plasmapheresis, as indicated. |

| Type 3 Hypersensitivity

(Immune Complex) |

Immune complexes formed between antibodies and antigens deposit in various tissues, leading to localized inflammation. | Immune complexes attract neutrophils, causing inflammation and tissue damage at the site of deposition. | Systemic lupus erythematosus and rheumatoid arthritis. | Anti-inflammatory medications. |

| Type 4 Hypersensitivity (Delayed) | Cell-mediated immune responses, mediated by T cells, cause inflammation and tissue damage. | Sensitized T cells recognize antigens and release cytokines that recruit inflammatory cells and induce tissue damage. | Contact dermatitis, tuberculin skin test reactions, and graft rejection. | Corticosteroids for severe reactions. |

Autoimmune Reactions

Autoimmune reactions (ŏ-tō-ĭ-mūn rē-ăk-shŏns) refer to actions within the body where one’s own immune system initiates a response against the body’s own healthy cells, tissues, or organs. When the body’s immune system is functioning correctly, the body can recognize bacteria, viruses, or any abnormal invader. In autoimmune reactions, the body cannot always distinguish its own healthy cells and begins to target immune actions inappropriately against itself.[5]

Graft Reactions

The transplantation of tissues to replace diseased organs is an important medical therapy used for a variety of diseases and disorders. Adaptive immune responses are major barriers to successful transplantation. Graft (grăft) refers to transplanted donated tissue or organs.

Graft rejection (grăft rĭ-jĕk-shŏn) is caused by the patient’s adaptive immune response to antigens on the donated graft that are interpreted as “foreign.” To help prevent graft rejection, tissue typing (i.e., matching) of the organ donor and the person receiving the organ is performed. The more similar the antigens are between the donor and recipient, the less likely that the organ will be rejected. Recipients of donated grafts must typically take immunosuppressive medications for their lifetime to prevent their immune system from attacking the transplanted tissue.

An opposite type of graft reaction can occur in donated bone marrow transplants called graft-versus-host disease (GVHD). Recall that “graft” refers to transplanted donated tissue or organs, and “host” refers to the tissues of the recipient. During GVHD, the transplanted bone marrow cells mount an immune response against the recipient’s tissues. GVHD occurs because the bone marrow cells being transplanted contain lymphocytes. Because the recipient’s bone marrow and adaptive immune response were destroyed with chemotherapy before receiving the bone marrow transplant, they cannot defend themselves against the attack. Patients undergoing bone marrow transplants receive preventative treatment with immunosuppressive medications for several months after the surgery to prevent GVHD. If GVHD does occur, the patient is treated with increased levels of immunosuppressive medications, as well as corticosteroids.

Cancer

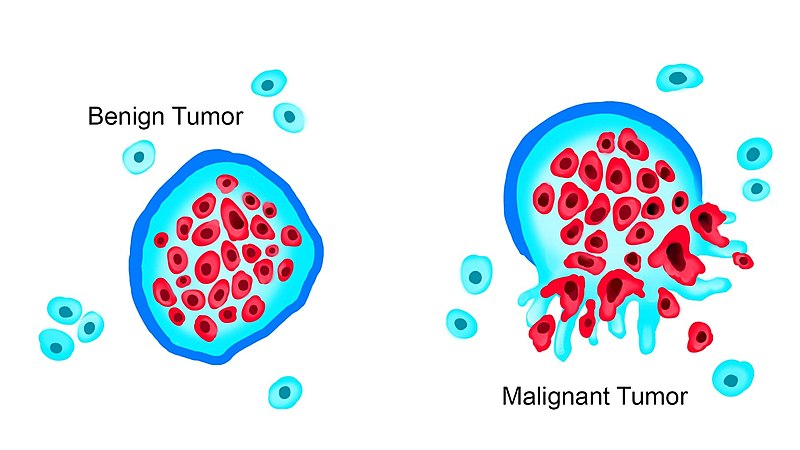

Cancer (KĂN-sŏr) refers to abnormal cells that overgrow and have the ability to invade and harm tissues. Malignant (mă-lĭg-nănt) cells differ from benign cells in that malignant cells exhibit uncontrolled growth and rapidly divide, subsequently invading and causing damage to normal functioning cells. Some cancers also disrupt apoptosis (ap-ŏp-TŌ-sĭs), programmed cell death to regulate cell population. Malignant cells also have the potential to metastasize, or spread, to different parts of the body. Benign (bĭ-nīn) cells grow and divide in a more controlled manner, remaining localized to a certain area.

Malignant cells are the most dangerous due to their ability to metastasize. When cells metastasize (mĕ-tăs-tă-sīz), they spread through the blood or lymphatic system. The spread of cancer cells and their rapid replication and invasion in other areas of the body complicate medical treatment, making it more difficult to rid the body of these abnormal invasive cells.[6] See Figure 11.8[7] for an illustration comparing benign and malignant tumors.

The distinction between benign and malignant growths is also reflected in the associated medical interventions and prognosis. Benign growth is typically managed through close monitoring and/or minimal surgical interventions. For example, a benign tumor may be surgically removed with no further medical treatment required. However, malignant growths require prompt, targeted medical interventions to prevent progression and metastasis of cancer to other areas of the body.[8]

Metastasis

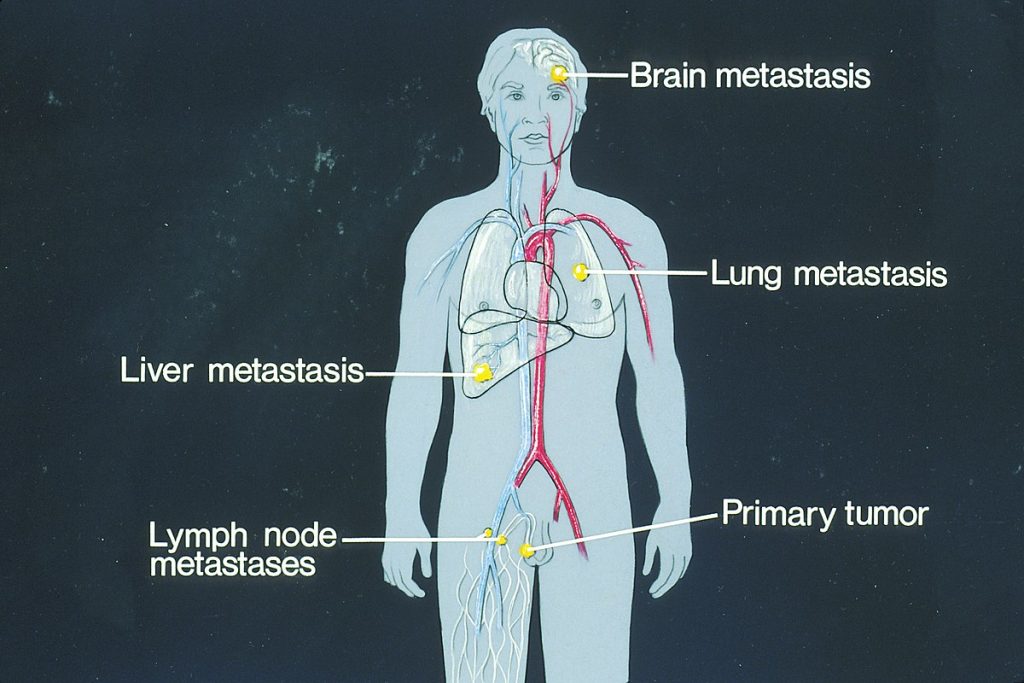

Metastasis of cancer cells can occur in different parts of the body. See Figure 11.9[9] for an illustration of metastasis of a primary tumor.

Common sites of metastasis include the following areas[10]:

- Lungs (lŭngz): The lungs are a frequent site of metastasis because they receive a large volume of blood from the body’s circulation. Cancer cells circulating in the bloodstream can easily lodge in the small blood vessels of the lungs, leading to secondary tumor formation.

- Liver (lĭv-ĕr): The liver plays a significant role in blood filtration, making it another common site for metastasis.

- Bones (bōnz): Many cancers, such as breast, lung, and prostate cancer, have a tendency to metastasize to the bones.

- Brain (brān): Cancer cells can reach the brain through the bloodstream.

- Lymph Nodes (limf nōdz): Lymph nodes play a role in filtering lymph. Tumors located in close proximity to the lymph nodes, especially breast, gastrointestinal, urological, gynecological, and some skin cancers, are more likely to spread through the lymphatic system.

- Small and Large Intestines (smôl ănd lärj in-TĔS-tĭnz): The small and large intestines, including the colon and rectum, are susceptible to metastasis, particularly in colorectal cancer. Cancer cells from the colon can also spread to nearby lymph nodes and to the liver.

- Adrenal Glands (ă-DRĒ-năl glăndz): The adrenal glands that sit atop the kidneys can be affected by metastatic cancer. The adrenal glands have a rich blood supply, making them potential targets for cancer cells circulating in the bloodstream.

- Skin (skĭn): Melanoma, a type of skin cancer, has a propensity to spread to other parts of the body, including distant skin sites and internal organs.

- Ovaries (Ō-vă-rēz): In women, ovarian metastasis can occur from cancers that have spread through the bloodstream or lymphatic system. Breast, colorectal, and stomach cancers are examples of cancers that can metastasize to the ovaries.

- Kidneys (KĬD-nēz): Kidney metastasis can occur when cancer cells from other parts of the body reach the kidneys through the bloodstream. The kidneys filter the blood, making them a potential site for cancer cells to become trapped.

Cancer-Causing Viruses

Some cancers are caused by viruses, such as liver cancer caused by the hepatitis B virus and cervical cancer caused by the human papilloma virus (hū-măn pă-pĭ-LŌ-mă vī-rŭs) (HPV). Both of these viruses have vaccines available to prevent disease, so vaccination can also help prevent cancer by stimulating the immune response. Kaposi’s sarcoma (kă-PO-sēz sär-KŌ-mă), caused by the herpes virus, is an example of cancer caused by a virus that is almost never observed in individuals with strong immune systems. See Figure 11.10[11] for an image of Kaposi’s sarcoma.

Immunodeficiencies

Immunodeficiency (im-yŭ-nō-dĕ-FISH-ĕn-sē) refers to inadequate immune response caused by immune system dysfunction. Someone who has an impaired or weakened immune system is referred to as immunocompromised (ĭm-yū-nō-KŎM-prō-mīzd).

Inherited immunodeficiencies arise from genetic mutations that affect specific components of the immune response. Individuals can also acquire immunodeficiencies, such as acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) caused by the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV).[12]

Inherited Immunodeficiencies

While many inherited immunodeficiencies exist, the most serious is severe combined immunodeficiency disease (sē-vēr kŏm-BĪND ĭm-yū-nō-dĕ-FISH-ĕn-sē dĭ-zēz) (SCID). This complex disease is caused by many different genetic defects that result in impaired B cell and T cell functioning of the adaptive immune response. Children with this disease usually die of opportunistic infections within their first year of life unless they receive a bone marrow transplant. Opportunistic infection (ŏp-ŏr-tū-NĬS-tĭk ĭn-FĔK-shŏn) are infections that occur more often or are more severe in people with weakened immune systems than in people with healthy immune systems. An example of an opportunistic infection is pneumonia caused by Candida, a type of yeast.[13]

Acquired Immunodeficiency

The human immunodeficiency virus (hū-măn ĭm-yū-nō-dĕ-FISH-ĕn-sē vī-rŭs) (HIV) can completely wipe out the functioning of an individual’s immune system if it progresses to acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (ādz ăk-wīrd ĭm-yū-nō-dĕ-FISH-ĕn-sē sĭn-drōm) (AIDS). HIV is transmitted through semen, vaginal fluids, and blood. The presence of detectable anti-HIV antibodies in a person’s blood indicates a positive HIV test, referred to as seroconversion (sē-rō-kŏn-VĔR-zhŏn).[14]

After seroconversion, the amount of HIV circulating in the blood drops and stays at a low level for several years. During this time, the levels of CD4 T cells (sē-dē fôr tē sĕlz), helper T cells, decline steadily, until at some point, the immune response is so weak that opportunistic diseases develop and eventually result in death. Treatment of HIV consists of drugs that target proteins necessary for viral replication but are absent from normal human cells. By targeting the virus itself and sparing the cells, this approach has been successful in significantly prolonging the lives of HIV-positive individuals.[15]

Lymphoma

Lymphoma (lĭm-FŌ-mă) is cancer that originates from the lymphatic system. There are two main types of lymphoma called Hodgkin lymphoma and non-Hodgkin lymphoma.

In Hodgkin lymphoma (HŎJ-kĭn lim-FŌ-mă), lymphocytes grow out of control, causing swollen lymph nodes and growths throughout the body. Treatments for Hodgkin lymphoma include chemotherapy, radiation therapy, targeted therapy (i.e., drugs or other substances that attack specific cancer cells with less harm to normal cells), and cancer immunotherapy. Hodgkin lymphoma can usually be cured if it is found and treated early.[16]

Non-Hodgkin lymphoma (nŏn-HŎJ-kĭn lim-FŌ-mă) (NHL) is a diverse group of blood cancers that includes all types of lymphoma except Hodgkin’s lymphomas. NHL is much less predictable than Hodgkin lymphoma and is more likely to metastasize. The prognosis depends on the type of white blood cell, the stage of the cancer, and the treatment options.[17]

- This work is a derivative of Health Alterations by Open RN and is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- This work is a derivative of Health Alterations by Open RN and is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- This work is a derivative of Health Alterations by Open RN and is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- This work is a derivative of Health Alterations by Open RN and is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- This work is a derivative of Health Alterations by Open RN and is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- This work is a derivative of Health Alterations by Open RN and is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- “Tumor_Types_MTK.jpg” by WolfpackBME is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0 ↵

- This work is a derivative of Health Alterations by Open RN and is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- “Sites_of_potential_metastases_illustration.jpg” by unknown author, via National Cancer Institute is licensed in the Public Domain. ↵

- This work is a derivative of Health Alterations by Open RN and is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- “Kaposis_Sarcoma_Lesions.jpg” by OpenStax College is licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0 ↵

- This work is a derivative of Anatomy & Physiology by OpenStax and is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Access for free at https://openstax.org/details/books/anatomy-and-physiology-2e ↵

- This work is a derivative of Anatomy & Physiology by OpenStax and is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Access for free at https://openstax.org/details/books/anatomy-and-physiology-2e ↵

- This work is a derivative of Anatomy & Physiology by OpenStax and is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Access for free at https://openstax.org/details/books/anatomy-and-physiology-2e ↵

- This work is a derivative of Anatomy & Physiology by OpenStax and is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Access for free at https://openstax.org/details/books/anatomy-and-physiology-2e ↵

- MedlinePlus [Internet]. Bethesda (MD): National Library of Medicine (US); [updated 2022, Apr. 4]. Hodgkin lymphoma; [cited 2023, Nov. 7]. https://medlineplus.gov/hodgkinlymphoma.html ↵

- National Cancer Institute. (2023, May 18). Non-Hodgkin lymphoma treatment (PDQ) - Health professional version. National Institutes of Health. https://www.cancer.gov/types/lymphoma/hp/adult-nhl-treatment-pdq ↵