11.2 Comfort Basic Concepts

Open Resources for Nursing (Open RN)

Definitions of Pain

Pain has historically been defined as, “Whatever the client says it is, experienced whenever they say they are experiencing it.”[1] In 2020 the International Association for the Study of Pain (IASP) released a revised definition of pain as, “An unpleasant sensory and emotional experience associated with, or resembling that associated with, actual or potential tissue damage,” along with these additional notes:

- Pain is always a personal experience that is influenced to varying degrees by biological, psychological, and social factors.

- Individuals learn the concept of pain throughout all stages of their life.

- A person’s report of an experience as pain should be respected.

- Although pain usually serves an adaptive role, it can have adverse effects on function, socialization, and psychological well-being.

- Verbal description is only one of several behaviors that express pain. The inability to communicate does not negate the possibility that a person is experiencing pain.[2]

Pain motivates the individual to withdraw from dangerous stimuli, to protect a damaged body part while it heals, and to avoid similar experiences in the future. Most pain resolves after the painful stimulus is removed and the body has healed, but sometimes pain persists despite removal of the stimulus and apparent healing of the body. Additionally, pain can occur in the absence of any detectable stimulus, damage, or disease.[3]

Physiology of Pain

Let’s begin by reviewing the physiological processes of pain. A nociceptor is a type of sensory receptor that responds to potentially damaging stimuli by sending nerve signals to the spinal cord and brain in a process called nociception. There are several types and functions of nociceptors:

- Thermal nociceptors are activated by noxious heat or cold, such as a hot pan.

- Mechanical nociceptors are activated by excess pressure or mechanical deformation, such as a finger getting caught in a car door. They also respond to incisions that break the skin surface.

- Chemical nociceptors are activated by a wide variety of spices commonly used in cooking. For example, capsaicin is a compound in chili peppers that causes a burning sensation of the mucus membranes. It is also used in common over-the-counter creams for pain relief because when it is applied to the skin, it blocks the transmission of pain impulses.[4]

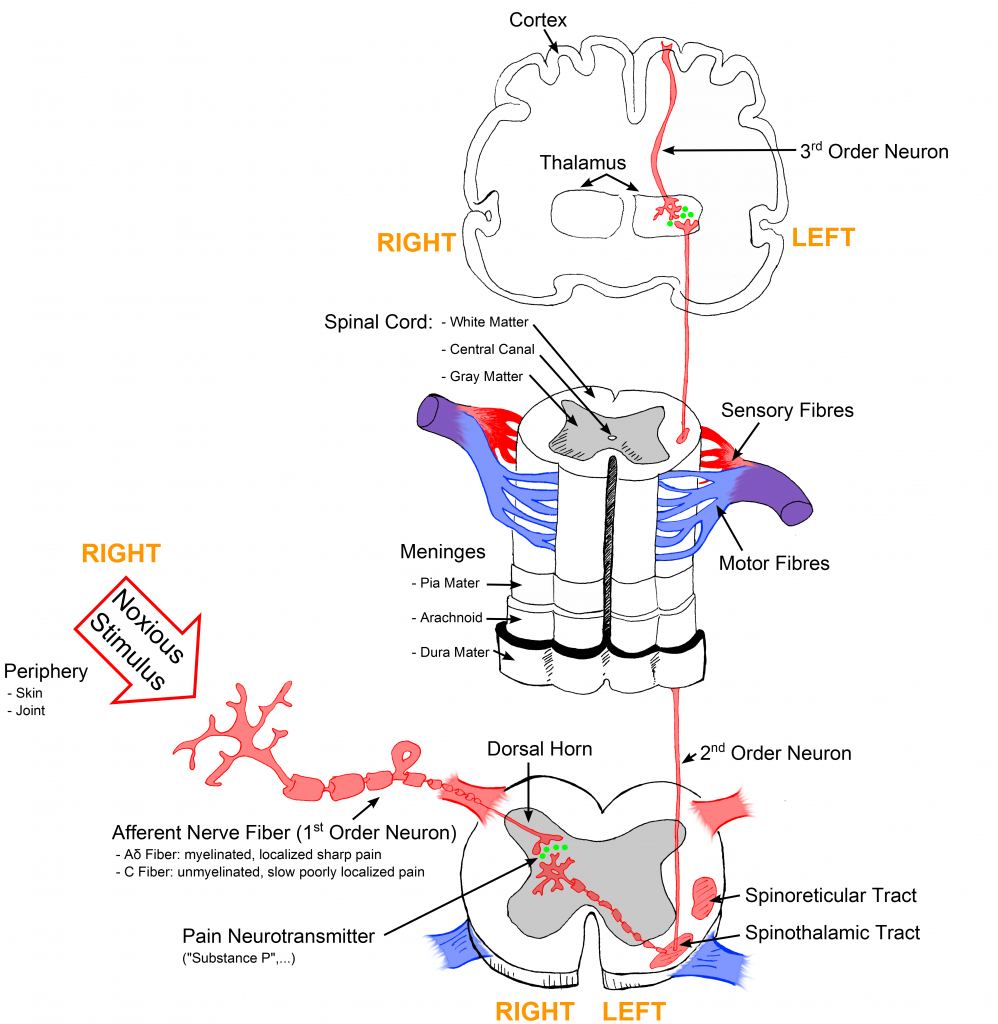

Noxious stimuli are detected by nociceptors and transduced into electrical energy. An action potential is created and transmitted along nociceptor fibers. There are two types of nociceptor fibers, A-Delta and C. A-Delta fibers are fast-conducting fibers and associated with the initial sharp, stinging, or pricking pain sensation. C fibers are slower-conducting fibers and are associated with the secondary sensation of diffuse, dull, burning, and aching pain. The pain impulse is transmitted along these nociceptor fibers to the dorsal horn in the spinal cord and then from the spinal cord to the thalamus, where pain messages are relayed to the cerebral cortex. In the cerebral cortex, pain impulses are perceived, and the conscious awareness of pain occurs.[5],[6] See Figure 11.1[7] for an illustration of how the pain signal is transmitted from the nociceptors to the spinal cord and then to the brain.

View supplementary TED Talk[8] and Medline Plus[9] videos on pain:

- Karen D. Davis: How does your brain respond to pain? | TED Talk

- A one-minute video review of how pain receptors work: Feeling Pain

Types of Pain

Pain can be divided into visceral, deep somatic, superficial, and neuropathic pain.

- Visceral structures are highly sensitive to stretch, ischemia, and inflammation. Visceral pain is diffuse, difficult to locate, and often referred to a distant, usually superficial, structure. It may be accompanied by nausea and vomiting and may be described as sickening, deep, squeezing, and dull.[10]

- Deep somatic pain is initiated by stimulation of nociceptors in ligaments, tendons, bones, blood vessels, fascia, and muscles and is a dull, aching, poorly localized pain. Examples include sprains and broken bones.[11]

- Superficial pain is initiated by the activation of nociceptors in the skin or other superficial tissue and is sharp, well-defined, and clearly located. Examples of injuries that produce superficial somatic pain include minor wounds and minor (first-degree) burns.[12]

- Neuropathic pain is defined by the International Association for the Study of Pain (IASP) as pain caused by a lesion or disease of the somatosensory nervous system. It is typically described by clients as “burning” or “like pins and needles.” Neuropathic pain can be caused by several disease processes, such as diabetes mellitus, strokes, and HIV, and is generally undertreated because it typically does not respond to analgesics. Medications such as tricyclic antidepressants and gabapentin are typically used to manage this type of pain.[13]

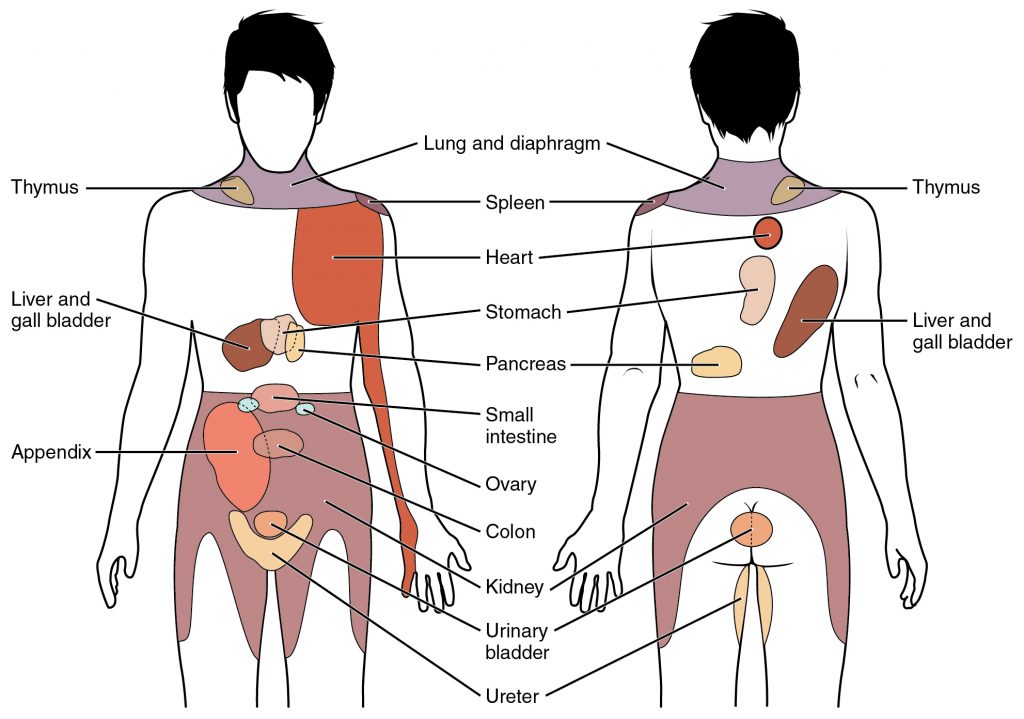

Pain can radiate from one area to another. For example, back pain caused by a herniated disk can cause pain to radiate down an individual’s leg. Referred pain is different from radiating pain because it is perceived at a location other than the site of the painful stimulus. For example, pain from retained gas in the colon can cause pain to be perceived in the shoulder. See Figure 11.2[14] for an illustration of common sites of referred pain.

Factors Affecting the Pain Experience

There are many biological, psychological, and social factors that affect the perception of pain, making it a unique, individual experience. See Table 11.2a for a list of these factors.[15] Nurses must consider these factors while assessing and providing holistic nursing care for clients experiencing pain.

Table 11.2a Biological, Psychological, and Social Factors Affecting Pain

| Biological Factors | Psychological Factors | Social Factors |

|---|---|---|

|

|

|

Acute vs. Chronic Pain

Pain is differentiated between acute pain and chronic pain. Acute pain has limited duration and is associated with a specific cause. It usually causes a physiological response resulting in increased pulse, respirations, and blood pressure. Diaphoresis (sweating, especially to an unusual degree) may also occur. Examples of acute pain include postoperative pain; burns; acute musculoskeletal conditions like strains, sprains, and fractures; labor and delivery; and traumatic injury.

Chronic pain is ongoing and persistent for longer than six months. It typically does not cause a change in vital signs or diaphoresis. It may be diffuse and not confined to a specific area of the body. Chronic pain often affects an individual’s psychological, social, and behavioral responses that can influence daily functioning. Chronic medical problems, such as osteoarthritis, spinal conditions, fibromyalgia, and peripheral neuropathy, are common causes of chronic pain. Chronic pain can continue even after the original injury or illness that caused it has healed or resolved. Some people suffer chronic pain even when there is no past injury or apparent body damage.

People who have chronic pain often have physical effects that are stressful on the body. These effects include tense muscles, limited ability to move around, lack of energy, and appetite changes. Emotional effects of chronic pain include depression, anger, anxiety, and fear of reinjury. These effects can limit a person’s ability to return to their regular work or leisure activities.[16] It is estimated that chronic pain affects 50 million U.S. adults, and 19.6 million of those adults experience high-impact chronic pain that interferes with daily life or work activities.[17] See Figure 11.3[18] for an illustration of low back pain, an example of both acute and chronic pain that often affects daily functioning.

Read additional information about pain using the following:

Life Span and Cultural Considerations

The pain experience varies across the life span. Newborns and infants can feel pain but are unable to verbalize it. Repetitive and prolonged pain may be associated with altered pain sensitivity and pain processing later in life. Toddlers and preschoolers often have difficulty describing, identifying, and locating pain. Instead, pain may be demonstrated behaviorally with crying, anger, physical resistance, or withdrawal. School-age children and adolescents may try to be “brave” and rationalize the pain; they are more responsive to explanations about pain.

Older adults are at increased risk for undertreatment of pain. It is estimated that up to 70% of older adults in the community and up to 85% living in long-term care centers have significant pain due to chronic conditions such as osteoarthritis and peripheral neuropathy. Pain is often underassessed in older adults because they are less likely to report it and also because it can present atypically with confusion and agitation.[19]

Other special populations who are at increased risk for the undertreatment of pain include the following:

- Clients with a history of addictive disease

- Nonverbal, cognitively impaired, or unconscious clients

- Clients who endure pain without complaining due to cultural or religious beliefs

- Non-English-speaking clients where communicating is a barrier

- Uninsured or underinsured clients where cost of medications is a barrier[20]

Nurses must be especially vigilant of nonverbal signs of pain in these at-risk groups and implement appropriate assessment tools and interventions. Read an example of a client with untreated pain in the following box.

A Story About Undertreated Pain

A teenage boy from the Amish community was admitted to the hospital after he sustained several fractures when his buggy was hit by a motor vehicle. His parents stayed at his bedside throughout his hospital stay. The nurses noticed that although he denied pain, he grimaced and guarded the body parts that were injured. He moaned when repositioned and declined to get out of bed to begin physical therapy when it was prescribed for rehabilitation. However, despite these nonverbal indicators of pain, he continued to deny the existence of pain and refused all pain medication. One day, when his parents left the room briefly to get coffee, the nurse said to the client, “Most people in your situation experience severe pain. I can see that you are hurting by your expressions when you move. Can you help me to understand why you don’t want any pain medication?” A tear began to fall down the boy’s cheek. He explained that his community does not believe in complaining about pain and to be a man, he must learn how to tolerate suffering. The nurse explained, “It is important for you to attend physical therapy so that you can heal and go home. Can we bring you pain pills every day before physical therapy so that you can participate in the exercises, recover quickly, and go home?” The boy agreed to this plan. The nurse documented her findings and made notes in the care plan to administer the prescribed PRN pain medications one hour before physical therapy was scheduled. She also communicated her findings during the nurse handoff report. The boy was able to satisfactorily complete the prescribed physical therapy and was discharged home the following week.

Use the following to read more information about treating pain:

- Treating pain in Special Populations

- The National Institute on Aging provides a wide range of information for older adults: Pain: You Can Get Help.

- Health in Aging offers additional information on pain management at Pain Management | Aging & Health AZ | American Geriatrics Society.

Standards of Care

Pain assessment and management standards were published in 2018 by The Joint Commission. The revised standards require hospitals to identify pain assessment and pain management, including safe opioid prescribing, as an organizational priority. Nurses are expected to implement these best practices. See Table 11.2b for a summary of associated requirements that must be incorporated into nursing care.[21] If these components are not included when providing nursing care, the hospital may be cited by The Joint Commission and potentially lose Medicare funding.

Table 11.2b The Joint Commission’s Pain Assessment and Management Requirements[22]

| Requirement | Rationale |

|---|---|

| Clients are screened for pain during emergency department visits and at the time of admission. | The misidentification and undertreatment of pain continue to occur in hospitals.

When a client presents to the hospital for other medical issues, pain may be overlooked or missed. Screening clients for pain or the risk of pain at the time of admission and while taking vital signs helps to improve pain identification and treatment. |

| Criteria to screen, assess, and reassess pain are used that are consistent with the client’s age, condition, and ability to understand. | An accurate screening and assessment are required for satisfactory pain management, and the hospital is responsible for ensuring that appropriate screening and assessment tools are readily available and used appropriately. |

| Clients are involved in the pain management treatment planning process by:

– Collaboratively developing realistic expectations and measurable goals for the degree, duration, and reduction of pain – Discussing the criteria used to evaluate treatment progress (for example, relief of pain and improved physical and psychosocial function) – Receiving education on pain management, treatment options, and safe use of opioid and nonopioid medications when they are prescribed |

Client involvement in planning pain management involves information sharing and collaboration between the client and provider to arrive at realistic expectations and clear goals. Numerous client factors may cause undertreatment or overtreatment of pain, such as pain expectations, knowledge of pain and its treatment, and underreporting of pain. Client involvement in the pain management planning process allows the provider to clarify the objectives of the process and guides clients in a manner that increases the likelihood of treatment adherence. |

| Client’s pain is treated, or they are referred for treatment.

Treatment strategies for pain may include nonpharmacologic, pharmacologic, or a combination of approaches. |

Referrals may be required for clients who present with complex pain management needs, such as a client with an opioid use disorder, a client who is at high risk for adverse events but requires treatment with opioids, or a client whose pain management needs exceed the expertise of the client’s provider. |

| Nonpharmacologic pain treatment modalities are promoted. | Nonpharmacologic modalities should be promoted by ensuring that client preferences are discussed and some nonpharmacologic treatment options provided. Nonpharmacologic strategies include, but are not limited to, physical modalities (e.g., acupuncture therapy, chiropractic therapy, osteopathic manipulative treatment, massage therapy, and physical therapy), relaxation therapy, and cognitive behavioral therapy. |

| Clients identified as being high risk for adverse outcomes related to opioid treatment are monitored. | The most dangerous adverse effect of opioid analgesics is respiratory depression.

Equipment must be available to monitor clients deemed highest risk (e.g., clients with sleep apnea, those receiving continuous intravenous opioids, or those on supplemental oxygen). |

| Clients experiencing opioid substance abuse are referred to opioid treatment programs. | When clinicians encounter clients who are addicted to opioids, the clients should be referred for treatment. The U.S. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration provides a directory of opioid treatment programs. |

| The hospital facilitates access to the Prescription Drug Monitoring Program databases. | Prescription Drug Monitoring Programs (PDMP) aggregate prescribing and dispensing data submitted by pharmacies and health care providers. They are an effective tool for reducing prescription drug abuse and diversion. Read more about PDMP in the “Legal/Ethical” chapter of the Open RN Nursing Pharmacology, 2e textbook. |

| Client’s pain is reassessed and responded to through the following:

Evaluation and documentation of: – Response to pain intervention(s) – Progress toward pain management goals, including functional ability (for example, the ability to take a deep breath, turn in bed, walk with improved pain control) – Side effects of treatment |

Reassessment should be completed in a timely manner to determine if the intervention is working or if the client is experiencing adverse effects. Only using a numerical pain scale to monitor a client’s pain is inadequate.

The Joint Commission’s technical advisory panel stressed the importance of assessing how pain affects function and the ability to make progress towards treatment goals. For example, immediately after major abdominal surgery, the goal of pain control may be the client’s ability to take a breath without excessive pain. Over the next few days, the goal of pain control may be the ability to sit up in bed or walk to the bathroom without limitation due to pain. |

| Clients and their family members are educated on discharge plans related to pain management, including the following:

– Pain management plan of care – Side effects of pain management treatment – Activities of daily living, including the home environment that might exacerbate pain or reduce effectiveness of the pain management plan of care, as well as strategies to address these issues – Safe use, storage, and disposal of opioids when prescribed |

During the discharge process, clients and families need education on the importance of how to manage the client’s pain at home. Unmanaged pain may cause a client to regress in their recovery process or have uncontrolled pain at home leading to a readmission to the hospital. It is necessary to have a discussion with clients and their families regarding their home environment and activities of daily living that may increase the need for pain management. When a client is being discharged with an opioid medication, education on safe use, including when and how much medication to take, should be included in the discharge plan. Opioid disposal education is also critical to both reduce diversion and decrease the risk of accidental exposure to someone other than the person for whom the opioid was prescribed. |

Read Pain Management Best Practices from the United States Department of Health & Human Services.

Pain Management and the Opioid Crisis

The American Nurses Association published a position statement in 2018 on the ethical responsibility of nurses to properly manage pain.[23] In 2019 the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services published Pain Management Best Practices.[24] Why is there continued emphasis on optimal pain management? Let’s review some trends related to pain management over the past few decades.

Trends Related to Pain Management

Pain assessment and pain management began to undergo significant changes in the 1990s when pain experts recognized that inadequate assessment and treatment of pain had become a public health issue. Recommendations for improving the quality of pain care were followed by initiatives that recognized clients’ reported pain as “the 5th vital sign.” Hospital administrators and regulators began to focus on pain scores, encouraging and incentivizing providers to aggressively treat pain to lower pain scores. These trends led to liberal prescribing of opioid pain medications for both acute and chronic pain.

Unfortunately, this increase in prescription of opioid pain medication led to a rise in misuse and overdose deaths related to opioid pain medications. Organizations began to urge caution about the use of opioids for pain, including guidelines published in 2016 by the Centers for Disease Control (CDC) on prescribing opioids for pain.[25] The 2016 CDC guideline led to limited prescriptions of opioids and unintended consequences, such as forced tapering of medications for established clients requiring chronic pain control and the transition of some clients desperate for pain control to using illicit drugs, such as heroin.

In 2022, the CDC released new guidelines for prescribing opioids for pain. The CDC recommends that people experiencing pain receive appropriate pain treatment, with careful consideration of the benefits and risks of all treatment options in the context of the client’s circumstances. The guidelines are intended to improve communication with clients about the benefits and risks of pain treatments, including opioid therapy; improve the effectiveness and safety of pain treatment; mitigate pain; improve function and quality of life for clients with pain; and reduce risks associated with opioid pain therapy, including opioid use disorder, overdose, and death.[26]

In this manner, pain management and the opioid crisis have influenced each other and continue to evolve. It is imperative for nurses to ensure that clients with painful conditions can work with their health care providers to develop pain treatment plans that balance pain control, optimize function, and enhance quality of life while also minimizing risks for opioid misuse and harm.[27]

Associated Definitions

When discussing pain management and the opioid crisis in the United States, it is important to understand the following terms:

- Opioid intoxication refers to significant behavioral or psychological changes (e.g., apathy, dysphoria, psychomotor agitation or retardation, or impaired judgment) that occur during or shortly after opioid use. Symptoms of opioid intoxication include drowsiness or coma, slurred speech, or impairment in attention or memory.[28]

- Overdose is the biological response of the human body when too much of a substance is ingested.

- Tolerance refers to a diminished effect with continued use of the same amount of an opioid, or a need for increased amounts of opioids to achieve the desired effect or intoxication.[29]

- Misuse refers to taking prescription pain medications in a manner or dose other than prescribed; taking someone else’s prescription, even if for a medical complaint such as pain; or taking a medication to feel euphoria (i.e., to get high).[30]

- Substance use disorder is an neurobiological illness caused by repeated misuse of substances (including opioids, which is specifically referred to as opioid use disorder). When taken in excess, these substances have a common effect of directly activating the brain reward system and producing such an intense activation of the reward system that normal life activities may be neglected. A person diagnosed with opioid use disorder has at least two of the symptoms listed below in a given year[31]:

- Opioids are taken in larger amounts or over a longer period of time than intended.

- There is a persistent desire or unsuccessful efforts to cut down or control opioid use.

- A great deal of time is spent in activities necessary to obtain the opioid, use the opioid, or recover from its effects.

- The person experiences craving, a strong desire or urge to use opioids.

- Recurrent opioid use results in the person’s failure to fulfill major role obligations at work, school, or home.

- Opioid use continues despite the person having persistent or recurrent social or interpersonal problems caused or exacerbated by the effects of opioids.

- Important social, occupational, or recreational activities are given up or reduced because of opioid use.

- Opioids are recurrently used in situations in which it is physically hazardous.

- Opioids are continued to be used despite the person having a persistent or recurrent physical or psychological problem that is likely to have been caused or exacerbated by the substance.

- The person experiences symptoms of tolerance to opioids.

- The person experiences withdrawal symptoms causing significant distress after stopping or reducing opioid use, with symptoms such as dysphoric mood, nausea, vomiting, muscle aches, rhinorrhea or lacrimation, pupillary dilation, piloerection, sweating, diarrhea, yawning, fever, or insomnia.

- Physical dependence refers to withdrawal symptoms that occur when an opioid is suddenly reduced or stopped because of physiological adaptations that occurwith chronic exposure to the medication.[32] For example, if a client who receives hydromorphone daily suddenly has their prescription stopped, they will likely experience symptoms of withdrawal, such as sweating, goose bumps, vomiting, anxiety, insomnia, and muscle pain.

- Addiction is a term used in many countries to describe severe problems related to compulsive and habitual use of substances. However, it is no longer a diagnosis by the American Psychiatric Association because of its potentially negative connotation.[33]

Recognizing and Treating Opioid Overdose

Five basic steps are recommended for nurses, first responders, health professionals, and other bystanders to rapidly recognize and treat opioid overdose to prevent death.[34]

- Recognize Signs of Opioid Overdose:

- Signs of opioid overdose include unconsciousness or the inability to awaken; pinpoint pupils; slow, shallow breathing; breathing difficulty manifested by choking sounds or a gurgling/snoring noise from a person who cannot be awakened; fingernails or lips turning blue or purple; or respiratory arrest

- If an opioid overdose is suspected, try to stimulate the person by calling their name or vigorously grinding one’s knuckles into their sternum.

- Obtain Emergency Assistance: If the person does not respond, call 911 or obtain emergency assistance.

- Provide Rescue Breathing, Chest Compressions, and Oxygen As Needed:

- Provide rescue breathing if the person is not breathing on their own. A barrier device is recommended to reduce the risk of disease transmission. Rescue breathing for adults involves the following steps:

- Be sure the person’s airway is clear.

- Place one hand on the person’s chin, tilt the head back, and pinch the nose closed.

- Place your mouth over the person’s mouth to make a seal and give two slow breaths.

- Watch for the person’s chest (but not the stomach) to rise.

- Follow up with one breath every five seconds.

- If the individual becomes pulseless, provide cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR).

- Administer oxygen as needed.

- Provide rescue breathing if the person is not breathing on their own. A barrier device is recommended to reduce the risk of disease transmission. Rescue breathing for adults involves the following steps:

- Administer the First Dose of Naloxone:

- Naloxone should be administered to anyone suspected of an opioid overdose.

- Research has shown that women, older adults, and those without obvious signs of opioid use disorder are undertreated with naloxone and, as a result, have a higher death rate. Therefore, naloxone should be considered for women and the elderly who are found unresponsive.

- Naloxone can be used in life-threatening opioid overdose circumstances in pregnant women.

- Naloxone can be given intranasally, intramuscularly, subcutaneously, or intravenously. The nasal spray is a prefilled device that requires no assembly and delivers a single dose into one nostril. An auto-injector is injected into the outer thigh to deliver naloxone intramuscularly or subcutaneously.

- All naloxone products are effective in reversing opioid overdose, including fentanyl-involved opioid overdoses, although overdoses involving potent or large quantities of opioids may require additional doses of naloxone.

- Withdrawal triggered by naloxone can feel unpleasant; some people may awaken confused, agitated, or aggressive. Provide safety, reassurance, and explain what is happening.

- Administer a Second Dose of Naloxone If the Person Does Not Respond:

- If the person overdosing does not respond within 2 to 3 minutes after administering a dose of naloxone, administer a second dose of naloxone.

- People who have taken long-acting or potent opioids (like fentanyl) may require additional intravenous bolus doses or an infusion of naloxone.

- The duration of effect of naloxone depends on dose, route of administration, and overdose symptoms. It is shorter than the effects of some opioids, so a second dose may be required.

- Monitor the Person’s Response:

- Most people respond to naloxone by returning to spontaneous breathing within two to three minutes. Continue resuscitation while waiting for the naloxone to take effect.

- The goal of naloxone therapy is to restore adequate spontaneous breathing but not necessarily achieve complete arousal.

- The individual should be monitored for recurrence of signs and symptoms of opioid toxicity for at least four hours from the last dose of naloxone. People who have overdosed on long-acting opioids like fentanyl patches require prolonged monitoring.

- Because naloxone has a relatively short duration of effect, overdose symptoms may return. Therefore, it is essential to get the person to an emergency department or other source of medical care as quickly as possible, even if the person revives after the initial dose of naloxone and seems to feel better.

Substance Use Disorder Among Nurses and Nursing Students

It is important to understand that substance use disorder is a neurobiological illness that can happen to anyone, including nurses and nursing students. The American Nursing Association released the following statements in 2016[35]:

- Health care facilities should provide education to nurses and other employees regarding alcohol and other drug use and establish policies, procedures, and practices to promote safe, supportive, drug-free workplaces.

- Health care facilities and schools of nursing should adopt alternative-to-discipline approaches to treating nurses and nursing students with substance use disorders, with stated goals of retention, rehabilitation, and reentry into safe, professional practice.

- Nurses and nursing students should be aware of the risks associated with substance use, impaired practice, and drug diversion and have the responsibility and means to report suspected or actual concerns.

- Pasero, C., & MacCaffery, M. (2010). Pain assessment and pharmacological management (1st ed.). Mosby. ↵

- International Association for the Study of Pain. (2017). IASP terminology. https://www.iasp-pain.org/Education/Content.aspx?ItemNumber=1698 ↵

- LibreTexts. (2024). Anatomy and physiology (boundless). LibreTexts: Medicine. https://med.libretexts.org/Bookshelves/Anatomy_and_Physiology/Anatomy_and_Physiology_(Boundless) ↵

- LibreTexts. (2024). Anatomy and physiology (boundless). LibreTexts: Medicine. https://med.libretexts.org/Bookshelves/Anatomy_and_Physiology/Anatomy_and_Physiology_(Boundless) ↵

- LibreTexts. (2024). Anatomy and physiology (boundless). LibreTexts: Medicine. https://med.libretexts.org/Bookshelves/Anatomy_and_Physiology/Anatomy_and_Physiology_(Boundless) ↵

- NursingTimes. (2008). Anatomy and physiology of pain. https://www.nursingtimes.net/clinical-archive/pain-management/anatomy-and-physiology-of-pain-18-09-2008/#:~:text=The%20transmission%20process%20occurs%20in,higher%20levels%20of%20the%20brain ↵

- "Sketch colored final.png" by Bettina Guebeli is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0) ↵

- Karen D. Davis. (2014, June). How does your brain respond to pain?. [Video]. TED-Ed. All rights reserved. https://www.ted.com/talks/karen_d_davis_how_does_your_brain_respond_to_pain?subtitle=en ↵

- ADAM. (n.d.). Feeling Pain [Video]. Medline Plus. All rights reserved. https://medlineplus.gov/ency/anatomyvideos/000054.htm ↵

- LibreTexts. (2024). Anatomy and physiology (boundless). LibreTexts: Medicine. https://med.libretexts.org/Bookshelves/Anatomy_and_Physiology/Anatomy_and_Physiology_(Boundless) ↵

- LibreTexts. (2024). Anatomy and physiology (boundless). LibreTexts: Medicine. https://med.libretexts.org/Bookshelves/Anatomy_and_Physiology/Anatomy_and_Physiology_(Boundless) ↵

- LibreTexts. (2024). Anatomy and physiology (boundless). LibreTexts: Medicine. https://med.libretexts.org/Bookshelves/Anatomy_and_Physiology/Anatomy_and_Physiology_(Boundless) ↵

- Murnion, B. P. (2018). Neuropathic pain: Current definition and review of drug treatment. Australian Prescriber, 41(3), 60–63. https://doi.org/10.18773/austprescr.2018.022 ↵

- “1506_Referred_Pain_Chart.jpg” by OpenStax is licensed under CC BY 3.0. Access for free at https://cnx.org/contents/C650g-ah@2/Autonomic-Reflexes-and-Homeostasis ↵

- Pain Management Best Practices Inter-Agency Task Force. (2019, May 9). Pain management best practices. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. https://www.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/pmtf-final-report-2019-05-23.pdf ↵

- Cleveland Clinic. (2020). Acute v. chronic pain. https://my.clevelandclinic.org/health/articles/12051-acute-vs-chronic-pain ↵

- Pain Management Best Practices Inter-Agency Task Force. (2019). Pain management best practices. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. https://www.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/pmtf-final-report-2019-05-23.pdf ↵

- “Lower_back_pain.jpg” by Injurymap is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- American Association of Colleges of Nursing. (n.d.). End-of-Life-Care (ELNEC). https://www.aacnnursing.org/ELNEC ↵

- American Association of Colleges of Nursing. (n.d.). End-of-Life-Care (ELNEC). https://www.aacnnursing.org/ELNEC ↵

- The Joint Commission. (2017). R3 report | Requirements, rationale, reference. https://www.jointcommission.org/-/media/tjc/documents/resources/patient-safety-topics/sentinel-event/r3_report_issue_11_pain_assessment_8_25_17_final.pdf?db=web&hash=938C24A464A5B8B5646C8E297C8936C1 ↵

- The Joint Commission. (2017). R3 report | Requirements, rationale, reference. https://www.jointcommission.org/-/media/tjc/documents/resources/patient-safety-topics/sentinel-event/r3_report_issue_11_pain_assessment_8_25_17_final.pdf?db=web&hash=938C24A464A5B8B5646C8E297C8936C1 ↵

- ANA Center for Ethics and Human Rights. (2018). Position statement: The ethical responsibility to manage pain and the suffering it causes. American Nurses Association. https://www.nursingworld.org/~495e9b/globalassets/docs/ana/ethics/theethicalresponsibilitytomanagepainandthesufferingitcauses2018.pdf ↵

- Pain Management Best Practices Inter-Agency Task Force. (2019, May 9). Pain management best practices. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. https://www.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/pmtf-final-report-2019-05-23.pdf ↵

- Cleveland Clinic. (2020). Acute v. chronic pain. https://my.clevelandclinic.org/health/articles/12051-acute-vs-chronic-pain ↵

- Dowell, D., Ragan, K. R., Jones, C. M., Baldwin, G. T., & Chou, R. (2022). CDC clinical practice guideline for prescribing opioids for pain — United States, 2022. MMWR Recommendation Report. http://doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.rr7103a1 ↵

- Pain Management Best Practices Inter-Agency Task Force. (2019). Pain management best practices. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. https://www.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/pmtf-final-report-2019-05-23.pdf ↵

- American Psychiatric Association. (2022). Desk reference to the diagnostic criteria from DSM-5-TR. ↵

- American Psychiatric Association. (2022). Desk reference to the diagnostic criteria from DSM-5-TR. ↵

- Pain Management Best Practices Inter-Agency Task Force. (2019). Pain management best practices. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. https://www.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/pmtf-final-report-2019-05-23.pdf ↵

- American Psychiatric Association. (2022). Desk reference to the diagnostic criteria from DSM-5-TR. ↵

- Pain Management Best Practices Inter-Agency Task Force. (2019). Pain management best practices. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. https://www.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/pmtf-final-report-2019-05-23.pdf ↵

- American Psychiatric Association. (2022). Desk reference to the diagnostic criteria from DSM-5-TR. ↵

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. (2018). SAMHSA opioid overdose prevention toolkit: Five essential steps for first responders [Manual]. U.S. Department of Health & Human Services. https://store.samhsa.gov/sites/default/files/d7/priv/five-essential-steps-for-first-responders.pdf ↵

- American Nurses Association. (2016). Substance use among nurses and nursing students. https://www.nursingworld.org/practice-policy/nursing-excellence/official-position-statements/id/substance-use-among-nurses-and-nursing-students ↵

An unpleasant sensory and emotional experience associated with, or resembling that associated with, actual or potential tissue damage.

A sensory receptor for painful stimuli.

Pain perceived at a location other than the site of the painful stimulus. For example, pain from retained gas in the colon can cause pain to be perceived in the shoulder.

Pain that is limited in duration and is associated with a specific cause.

Pain that is ongoing and persistent for longer than six months.

refers to significant behavioral or psychological changes (e.g., apathy, dysphoria, psychomotor agitation or retardation, or impaired judgment) that occur during or shortly after opioid use

The biological response of the human body when too much of a substance is ingested.

A diminished effect with continued use of the same amount of an opioid, or a need for increased amounts of opioids to achieve the desired effect or intoxication.

Taking prescription pain medications in a manner or dose other than prescribed; taking someone else’s prescription, even if for a medical complaint such as pain; or taking a medication to feel euphoria (i.e., to get high).

An illness caused by repeated misuse of substances (including opioids). When taken in excess, these substances have a common effect of directly activating the brain reward system and producing such an intense activation of the reward system that normal life activities may be neglected.

Symptoms that cause significant distress after stopping or reducing the use of substances (including opioids), with symptoms such as dysphoric mood, nausea, vomiting, muscle aches, rhinorrhea or lacrimation, pupillary dilation, piloerection, sweating, diarrhea, yawning, fever, or insomnia.

Withdrawal symptoms that occur when chronic pain medication is suddenly reduced or stopped because of physiological adaptations that occur from chronic exposure to the medication.

A term used in many countries to describe severe problems related to compulsive and habitual use of substances.