6.2 Nutrition and Fluid Needs

Nursing assistants (NAs) help clients meet their nutritional and fluid needs as they assist them with their activities of daily living. Let’s begin by reviewing the anatomy and physiology of the gastrointestinal system.

Anatomy and Physiology of the Gastrointestinal System

The gastrointestinal system (also referred to as the digestive system) is responsible for several functions, including digestion, absorption, and immune response. Digestion begins at the mouth, where chewing of food occurs. This is called mechanical digestion. If food is not broken down mechanically by the teeth, it is very difficult to digest, and it also increases the risk of choking. If there are any concerns with missing or broken teeth, dentures that don’t fit well, or any pain or open areas in the mouth, the NA should report these concerns to the nurse immediately.

After food is chewed and swallowed, it goes into the stomach via the esophagus. Involuntary movement, called peristalsis, allows the food to enter the stomach to mix with acidic gastric juices. The breaking down of food with these acids is called chemical digestion. From the stomach, the liquid food (called chyme) passes through the small and large intestine where nutrients and water are absorbed into the bloodstream. Waste products are condensed into feces and excreted through the anus.[1],[2] More information on the structure and function of the digestive system will be covered in Chapter 11.

Appropriate food and fluid intake are essential to good health, so anything that potentially decreases a client’s appetite must be addressed. For example, all five senses decline in functioning to some extent in older adults. It is important for the NA to provide accommodations that address these declines in sensory function that can impact food intake and overall health. Enhancing food intake in older adults with altered sensory function includes the following accommodations:

- Vision

-

- If the resident is known to wear glasses, ensure they are wearing them, and the lenses are clean. Seeing food often stimulates the desire to eat.

- Explain what is on the meal tray if the client has significant visual impairment. It is helpful to use the “clock method,” such as, “On your plate, your peas are at 3 o’clock, your roast beef is at 6 o’clock, and your mashed potatoes are at 9 o’clock.”

- If a resident has a pureed diet order, review their menu so you can describe each type of food in an appealing manner.

- Make meals look as attractive as possible. Take food off trays and avoid using plastic utensils and disposable cups whenever possible so the resident feels as if they are having a meal at home.

- Hearing

- If the resident has hearing aids, ensure they are in place, charged, and functioning so they can hear you describe the food.

- Ask if music is preferred during mealtime.

- When seating residents in a public eating area, ensure they are seated with others with similar cognitive status so they may enjoy conversation while eating.

- Touch

- Encourage the resident to eat as independently as possible by using adaptive silverware or other meal aids. Occupational therapists can assess the needs of the resident and provide adaptive equipment.

- If utensils can’t be held by the resident, try using finger foods such as fruit, bread, or crackers.

- Smell

- If possible, dietary staff should prepare meals near resident rooms because the aroma of cooking food may increase hunger.

- If a client is eating a meal in their room, clear the room of unpleasant odors or sights. For example, empty the trash can if it has soiled incontinence products, and empty urinals that may be sitting on side tables.

- Taste

- Check the diet order. If the order permits, ask residents if they prefer seasoning or condiments.

- Ensure hot foods are served hot and cold foods are served cold. Judge the temperature of the food by placing your hand above the food to sense heat, but do not touch the food directly with your hand. Rewarm hot foods that have cooled.

- If the resident does not like the meal choice, find an alternative food that appeals to them.

Refer to the “Assisting With Nutrition and Fluid Needs” section and the checklist “Preparing Clients for Meals and Assisting With Feeding” in Chapter 5 for specific steps and additional insight on feeding a dependent client.

Macronutrients

In hospitals and long-term care facilities, the dietician assesses clients periodically to ensure that their nutritional and fluid needs are met. However, when providing care in a group home, assisted living, or home health, NAs are often responsible for creating meals. It is important to understand basic nutritional concepts so you can address your clients’ nutritional needs.

Macronutrients make up most of a person’s diet and provide energy, as well as essential nutrient intake. Macronutrients include carbohydrates, proteins, and fats. However, too many macronutrients without associated physical activity cause excess nutrition that can lead to obesity, cardiovascular disease, diabetes mellitus, kidney disease, and other chronic diseases. Conversely, too few macronutrients contribute to nutrient deficiencies and malnourishment.[3]

Carbohydrates are sugars and starches and are an important energy source. Each gram of carbohydrates provides four calories. Carbohydrates break down into glucose and raise blood sugar levels. Diabetics should limit carbohydrate intake to maintain blood sugar levels in a healthy range.

Proteins are peptides and amino acids that provide four calories per gram. Proteins are necessary for tissue repair and function, growth, energy, fluid balance, clotting, and the production of white blood cells.

Fats consist of fatty acids and glycerol and are essential for tissue growth, insulation, energy, energy storage, and hormone production. Each gram of fat provides nine calories. While some fat intake is necessary for energy and the absorption of fat-soluble vitamins, excess fat intake contributes to heart disease and obesity. Due to its high-calorie content, a little fat goes a long way.[4]

Fats are classified as saturated, unsaturated, and trans fatty acids. Saturated fats come from animal products, such as butter and red meat (e.g., steak). Saturated fats are solid at room temperature. Recommended intake of saturated fats is less than 10% of daily calories because saturated fat raises cholesterol and contributes to heart disease.[5]

Unsaturated fats come from oils and plants, although chicken and fish also contain some unsaturated fats. Unsaturated fats are healthier than saturated fats. Examples of unsaturated fats include olive oil, canola oil, avocados, almonds, and pumpkin seeds. Fats containing omega-3 fatty acids are considered polyunsaturated fats and help lower cholesterol levels. Fish and other seafood are excellent sources of omega-3 fatty acids.[6]

Trans fats are fats that have been altered through a hydrogenation process, so they are not in their natural state. During the hydrogenation process, fat is changed to make it harder at room temperature and have a longer shelf life. Trans fats are found in processed foods, such as chips, crackers, and cookies, as well as in some margarines and salad dressings. Minimal trans-fat intake is recommended because it increases cholesterol and contributes to heart disease.[7]

Choosing Food Groups to Meet Macronutrient Needs

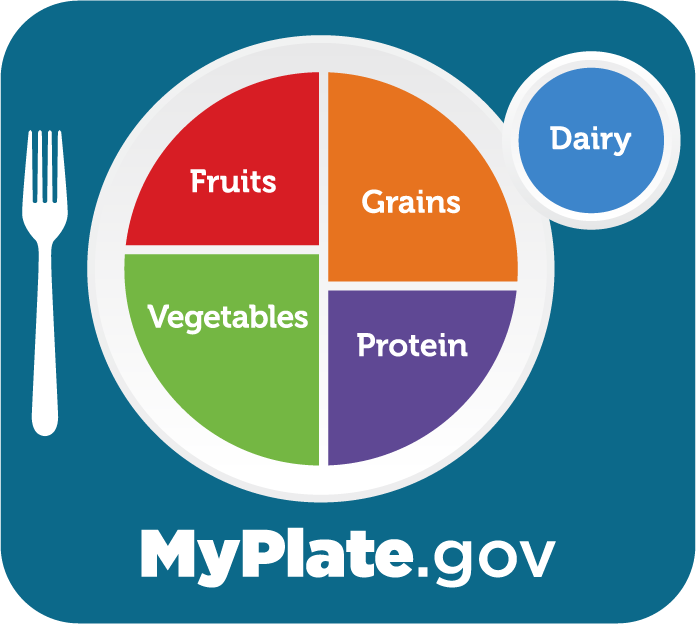

Good resources for healthy nutritional choices are the USDA’s “My Plate” guidelines.[8] By using a plate as a visual, sections on the plate illustrate general amounts of the different types of food groups that should be eaten every meal, including fruits and vegetables, grains, protein, and dairy. See Figure 6.1[9] for an image of the USDA’s “My Plate” guidelines.

About half the plate should be fruits and vegetables that provide many nutrients, as well as fiber for healthy bowel elimination. Fruits and vegetables are low in fat and calories and have no cholesterol. Fresh fruits and vegetables are the best choice, but frozen options have similar nutritional value. Frozen produce can also be more cost-effective because it doesn’t spoil and can save time as the food is already cleaned and chopped. A variety of colors of fruits and vegetables not only makes the plate visually appealing, but also provides the greatest array of nutrients.

About 25% of the plate should be grains. Pasta, cereal, and bread are sources of grains. Types of grains include wheat, corn, rice, oats, barley, and quinoa. Grains are low in fat and cholesterol but have high carbohydrate and fiber content. The fiber content in grains can be helpful in preventing constipation and lowering cholesterol. Due to the high carbohydrate content of grains, they may need to be limited for clients with diabetes.

The remaining 25% of the plate should contain protein sources. Common proteins include soy, quinoa, eggs, fish, meat, nuts and seeds, legumes (beans), and dairy products. Just as with the other food groups, a variety of protein selections provides the most nutrients. Red meat can contain a lot of fat and cholesterol, so lean cuts are preferred for heart health. Fish, especially salmon, has healthy fat and should be consumed twice weekly. Nuts, seeds, and legumes are low in saturated fat and high in fiber, which also make them a good choice for protein.

Dairy choices are important for calcium intake that aids in bone health. Calcium intake is important for older adults because they naturally retain less calcium and are at higher risk for bone fractures. Dairy products include milk, lactose-free milk, soy milk, buttermilk, cheese, yogurt, and kefir. Sour cream and cream cheese are not considered dairy items in terms of nutritional benefits. Adults should consume about three cups of dairy per day.

Choosing whole foods that are unprocessed, or as close to their original form as possible, is important to feeling full and stabilizing blood sugar because it takes longer to digest unprocessed foods. Think about eating an apple as compared to drinking apple juice. The whole apple will take a long time to chew and chemically break down to chyme, whereas the juice is ready to move through the digestive tract immediately. Eating whole foods can also reduce salt, fat, and sugar intake because they have no additives and can keep blood pressure, blood sugar, and cholesterol levels lower.

Read additional information about My Plate guidelines at https://www.myplate.gov/.

Fluid Intake

Fluid intake comes from both liquids and foods. For example, most fruits and vegetables contain a lot of water, so they contribute to fluid intake. See Table 6.2[10] for water content in various foods.

Table 6.2 Water Content in Foods

| Percentage | Food Items |

|---|---|

| 90-99 | Nonfat milk, cantaloupe, strawberries, watermelon, lettuce, cabbage, celery, spinach, squash |

| 80-89 | Fruit juice, yogurt, apples, grapes, oranges, carrots, broccoli, pears, pineapple |

| 70-79 | Bananas, avocados, cottage cheese, ricotta cheese, baked potato, shrimp |

| 60-69 | Pasta, legumes, salmon, chicken breast |

| 50-59 | Ground beef, hot dogs, steak, feta cheese |

| 40-49 | Pizza |

| 30-39 | Cheddar cheese, bagels, bread |

| 20-29 | Pepperoni, cake, biscuits |

| 10-19 | Butter, margarine, raisins |

| 1-9 | Walnuts, dry-roasted peanuts, crackers, cereals, pretzels, peanut butter |

| 0 | Oils, sugars |

The average fluid intake in adults per day is 1.5 liters of fluids with additional 700 milliliters (mL) of water gained from solid foods. About 2.5 liters of fluid are excreted daily in adults in urine, feces, respiration, and other body fluids like sweat and saliva.[11]

There is some debate over the amount of water required to maintain health. There is no consistent scientific evidence proving that drinking a particular amount of water improves health or reduces the risk of disease. Additionally, the amount of fluids a person consumes daily is variable and based on their climate, age, physical activity level, and kidney function.[12]

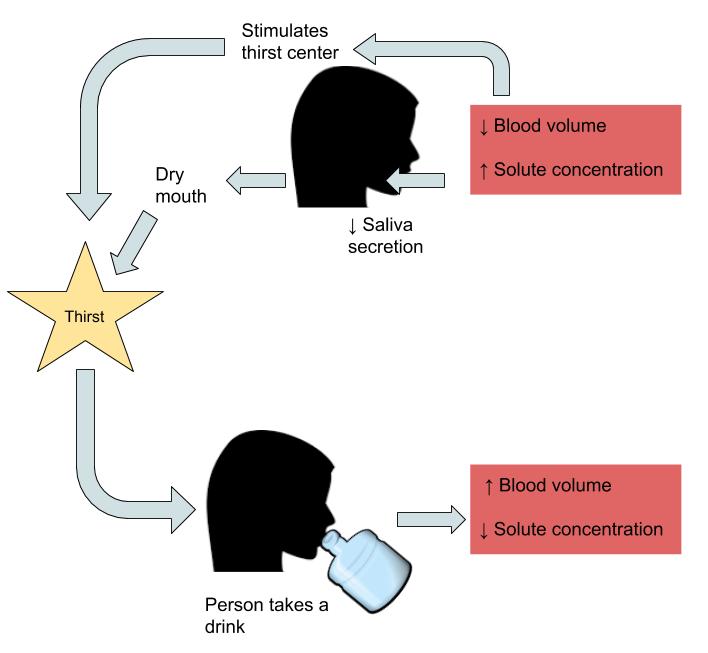

Our bodies are constantly trying to balance our fluid volume using the physiological mechanisms of thirst and urine output. The “thirst center” is contained within the hypothalamus, a portion of the brain that lies just above the brain stem. As people age, their thirst mechanism becomes less responsive, causing a higher risk of dehydration. See Figure 6.2[13] for an illustration of the thirst response. Thirst occurs in the following sequence of physiological events:

- Receptors in the kidney, heart, and hypothalamus detect decreased fluid volume or increased sodium concentration in the blood.

- Hormonal and neural messages are relayed to the brain’s thirst center in the hypothalamus.

- The hypothalamus sends neural signals stimulating the conscious thought to drink.

- Fluids are consumed.

- Receptors in the mouth and stomach detect mechanical movements involved with fluid ingestion.

- Neural signals are sent to the brain and the thirst mechanism is shut off.[14]

Thirst is a subconscious physiological mechanism to stimulate water intake. However, actual fluid intake is controlled by conscious eating and drinking habits that are influenced by cognitive, social, and cultural factors. For example, some individuals have a habit of drinking a glass of orange juice, coffee, or milk every morning before going to school or work. Conversely, older adults often have decreased fluid intake due to physical or cognitive challenges in obtaining or drinking fluids. For this reason, older adults often require assistance to maintain a healthy intake of fluids.

Due to the decreased thirst response in older adults, it is important to prevent dehydration by encouraging fluid intake even when they don’t feel thirsty. Dehydration can lead to confusion, falls, and bladder infections. Signs of dehydration include the following[15]:

- Dry mouth or other mucous membranes

- Dry skin or skin that does not return to normal shape when gently pinched

- Dark urine or urine amounts smaller than 200-300 mL

- Headache

- Dizziness

- Rapid heart rate

- Low blood pressure

If signs or symptoms of dehydration are noted, these concerns should be reported to the supervising nurse, and fluid intake should be encouraged as tolerated.

In hospitals and long-term care facilities, dieticians often determine the amount of daily fluid intake for clients. Fluid restrictions may be prescribed by the health care provider based on the client’s medical condition. Fluid restrictions are further discussed in the following “Modified Diets” subsection.

Cultural and Religious Considerations With Nutritional Intake

Cultural and religious beliefs often influence a client’s food selection and food intake. Dieticians and nurses assess a client’s cultural and religious preferences on admission to a facility, but NAs should continually ask clients about their food and fluid preferences. A particular diet should never be assumed based on a client’s stated culture or religion.

Cultural beliefs may affect the types of food eaten, as well as when they are eaten. Some foods may be restricted due to cultural beliefs or religious rituals, whereas other foods may be viewed as part of the healing process. For example, some individuals choose not to eat pork because of cultural or religious beliefs that consider pork unclean. Other individuals choose to eat “kosher” food because its method of preparation fits with their religious guidelines. Additionally, some individuals avoid eating during certain times. For example, some clients’ religious beliefs encourage fasting on religious holidays from sunrise to sunset, whereas other individuals avoid eating meat during their religious season of Lent.[16]

Modified Diets

Some individuals require limitations of certain foods or fluids due to medical circumstances, illnesses, or chronic diseases. For these reasons, the provider may order a modified diet, also referred to as a “therapeutic diet,” based on recommendations from a dietician. A modified diet is any diet altered to include or exclude certain components. For example, a client may have a modified diet order due to an upcoming test or procedure, a specific medical condition like diabetes, an allergy like a gluten allergy, or to lose weight.

As previously discussed in Chapter 5, it is critical for the NA to verify the diet orders for every client and then verify the food and fluids on their meal trays are correct based on the diet order. Here are some of the most common diet orders:

- Low-Sodium: Salt intake is commonly restricted for individuals with high blood pressure, heart failure, and kidney disease. Salt substitutes may be offered and high sodium condiments, such as ketchup, soy, barbecue and steak sauces, are avoided. This diet is commonly abbreviated as Low NA (sodium) or NAS (No added salt/sodium).

- Low-Fat: A low-fat diet is commonly prescribed for individuals with high cholesterol, heart disease, or arterial circulation problems. High-fat dairy and meat products, fried foods, desserts, and baked goods are avoided. However, healthy fats can be consumed from plant-based sources such as olive oil, nuts, avocados, and salmon.

- Low-Residue or Low-Fiber: Low-residue or low-fiber diets are commonly prescribed for individuals with bowel disorders. Fiber is found in grains, seeds, fruits, and vegetables, so these food choices are typically avoided.

- Diabetic or Carb-Controlled: Carb-controlled diets are typically prescribed for individuals with diabetes to help keep their blood sugar in a healthy range. This diet includes reduced intake of carbohydrates, especially from processed sources such as juices, starches such as potatoes and bread, and cereal or pasta that is not whole grain. Good carbohydrate sources include whole fruits and vegetables. Fat intake may also be restricted because it can elevate blood sugar levels. This diet is commonly abbreviated as CHO or CCHO. Many clients with diabetes have orders for a bedside blood glucose test before eating; ensure this test is completed and/or reported to the nurse.

- Gluten-Free: The gluten-free diet is typically prescribed for people with gastrointestinal conditions such as celiac disease or irritable bowel syndrome because their symptoms are aggravated by gluten. Gluten is found in wheat, rye, and barley, so rice, oats, and quinoa are good substitutes. There are many gluten-free pasta, cereal, and bread products available.

- Lactose-Free: Lactose is removed from the diet for individuals who are lactose intolerant. Lactose is found in milk and dairy products. Soy, almond, or rice milk are good substitutes that provide calcium.

- Fluid Restriction: Fluid restriction orders may be temporary, such as several hours before surgery, or permanent, such as for clients with kidney failure or heart failure. The provider prescribes the amount of fluid a person should consume in one day. In a hospital or facility, this amount is typically split across shifts based on meal and snack times while also taking into consideration fluids consumed with medications. Clients on fluid restrictions will also have their fluid intake and output tracked and documented daily as previously discussed in Chapter 5.

- NPO: NPO is a common medical abbreviation referring to “nothing by mouth.” NPO may be a temporary order, such as 8-12 hours before surgery, or a permanent order, such as for an individual with a permanent feeding tube due to dysphagia. Dysphagia refers to difficulty swallowing that can cause aspiration of liquids and food into one’s lungs and lead to life-threatening pneumonia. Individuals with severe dysphagia may never be able to eat or drink anything without risking pneumonia. Their nutrition is typically given through a permanent tube placed directly into their stomach (i.e., a PEG tube), or if it is a temporary condition, a tube is inserted through their nose into the stomach (i.e., an NG tube). Residents who are NPO do not typically desire to go to the dining room during meals because they can’t eat a regular diet, but be sure to ask their preference.

Diet Texture

In addition to modified diet orders regarding the content of the food choices, the texture of the food may also be modified based on the chewing and swallowing ability of the resident. Common orders for diet textures for residents include regular, mechanical soft, or pureed:

Regular Diet: Regular diets include any texture of food.

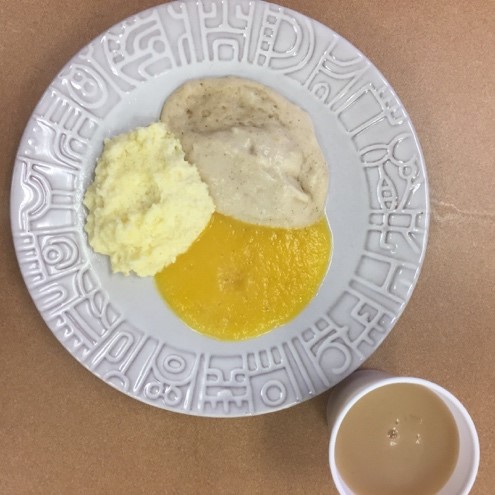

Mechanical Soft: Mechanical soft diets include food that is soft or easily mashed with a utensil. Meat is ground to make chewing easier. Fruits and vegetables are boiled to soften any skin, and sometimes it is removed. See Figure 6.3[17] for an image of a mechanical soft diet.

Pureed: Pureed diets include food that is blended to the consistency of a thick paste. See Figure 6.4[18] for an image of a pureed diet.

Liquid Consistency

Clients may require a specific type of liquid consistency if they have dysphagia and increased risk for aspiration. The flap that covers the trachea and prevents liquids from entering the lungs when swallowing is called the epiglottis. If the epiglottis loses muscle tone, liquid can seep around it into the lungs and cause aspiration pneumonia. Signs of possible dysphagia are when a client continually coughs or clears their throat while eating or drinking. These signs should be reported immediately to the nurse because it can indicate early stages of dysphagia.

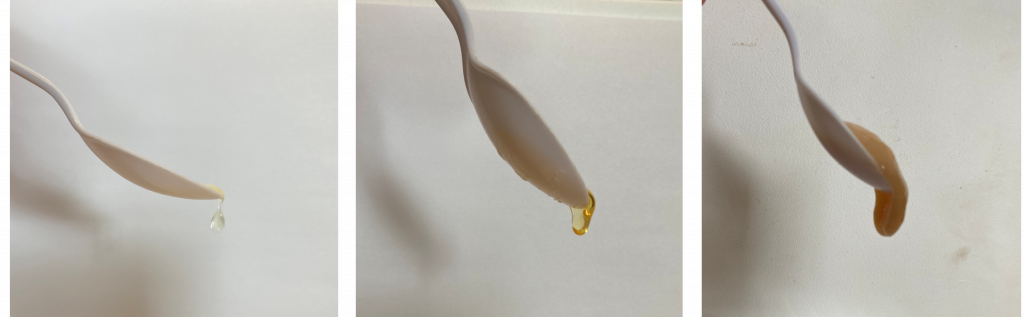

Clients with dysphagia typically have orders for thickened liquids. Thickened liquids are easier for the epiglottis to prevent from entering the lungs. Here are common types of liquid consistencies ordered:

Regular or Thin Liquids: No modifications for liquid consistency are required.

Nectar Thick (NT): Fluids are modified to have the consistency of thicker juices like a creamy soup.

Honey Thick (HT): Fluids are modified to have the consistency of honey or syrup that pour very slowly and may be consumed with a spoon.

Pudding Thick (PT): Fluids are modified to have semi-solid consistency like pudding. A spoon stands up in pudding-thick liquid.

See Figure 6.5[19] for an illustration comparing liquid consistency.

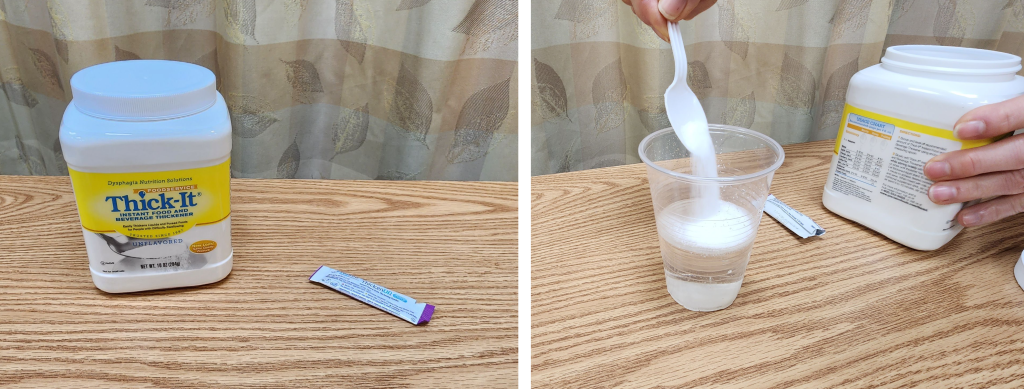

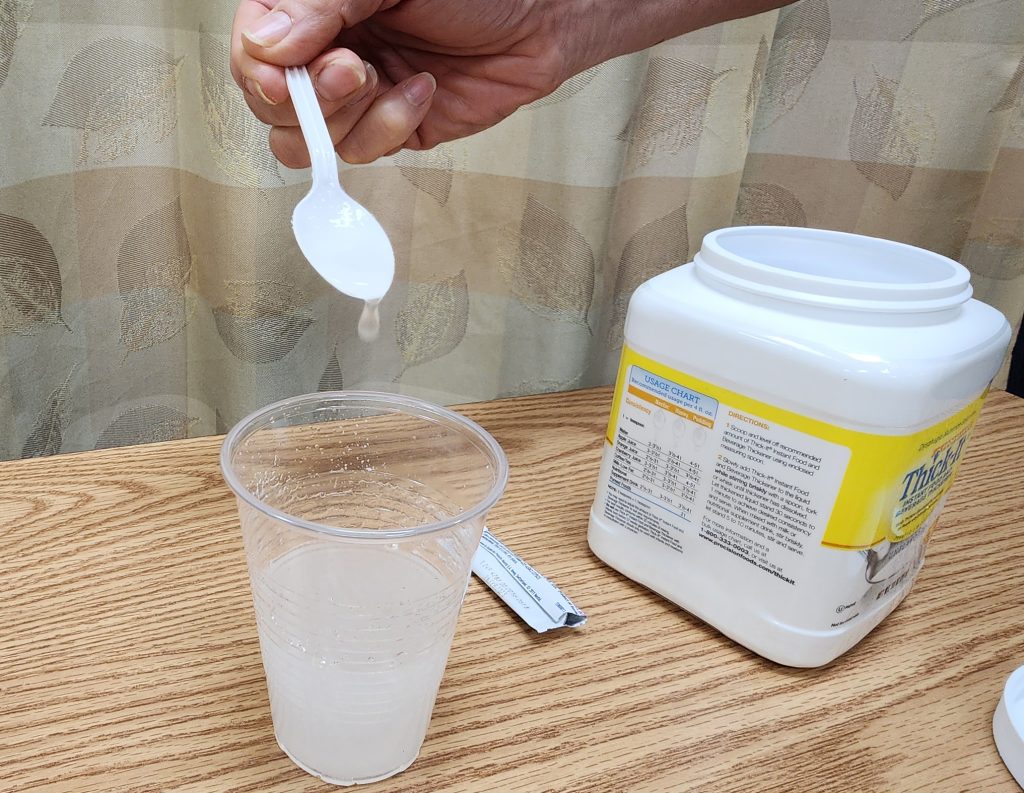

Liquids can be thickened using thickening powder. Pre-thickened liquids from manufacturers typically have a smoother consistency than prepared liquids. See Figure 6.6[20] for an image of a commercial thickening powder in use. Thickening liquid with powder requires exact attention to measurements to ensure the resident receives the correct liquid consistency and does not aspirate the fluid. Ice cubes should not be added to thickened liquids because as they melt, the liquid will become thinner. See Figure 6.7[21] for an image of thickening water.

Read additional information on modified diets and liquid consistencies in the Virginia Department of Behavioral Health and Developmental Services PDF.

- This work is a derivative of Nursing Fundamentals by Chippewa Valley Technical College and is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- This work is a derivative of Anatomy and Physiology by Boundless and is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0 ↵

- This work is a derivative of Nursing Fundamentals by Chippewa Valley Technical College and is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- This work is a derivative of Nursing Fundamentals by Chippewa Valley Technical College and is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- This work is a derivative of Nursing Fundamentals by Chippewa Valley Technical College and is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- This work is a derivative of Nursing Fundamentals by Chippewa Valley Technical College and is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- This work is a derivative of Nursing Fundamentals by Chippewa Valley Technical College and is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- MyPlate.gov. (n.d.). What is MyPlate? U.S. Department of Agriculture. https://www.myplate.gov/eat-healthy/what-is-myplate ↵

- “MyPlate_blue.png” by USDA is licensed under CC0 ↵

- This image is a derivative of “Table 3.1 Water Content in Foods” by University of Hawai‘i at Mānoa Food Science and Human Nutrition Program and is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 ↵

- Human Nutrition by University of Hawai‘i at Mānoa Food Science and Human Nutrition Program is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- Human Nutrition by University of Hawai‘i at Mānoa Food Science and Human Nutrition Program is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- “Regulating-Water-intake-.jpg” by Allison Calabrese is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Access for free at https://pressbooks.oer.hawaii.edu/humannutrition/chapter/regulation-of-water-balance/ ↵

- Human Nutrition by University of Hawai‘i at Mānoa Food Science and Human Nutrition Program is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- Human Nutrition by University of Hawai‘i at Mānoa Food Science and Human Nutrition Program is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- This work is a derivative of Nursing Fundamentals by Chippewa Valley Technical College and is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- “dysphagia-meat-and-potatoes-1w03r35.jpg” by Savannah Greiner is used with permission. Access for free at https://sites.udel.edu/chs-udfoodlab/2017/04/10/learning-about-dysphagia/ ↵

- “dysphagia-pureed-breakfast-1kl60uo.jpg” by Savannah Greiner is used with permission. Access for free at https://sites.udel.edu/chs-udfoodlab/2017/04/10/learning-about-dysphagia/ ↵

- “Honey Thick Liquid,” “Pudding Thick,” and “Thin Liquid” by Open RN Project are licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- “Powdered Thickener" and "Adding Thickener to Water" by Landon Cerny are licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- “Thickened Water” by Landon Cerny is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

Include carbohydrates, proteins, and fats.

Any diet altered to include or exclude certain components.

Common medical abbreviation referring to “nothing by mouth.”

Difficulty swallowing that can cause aspiration of liquids and food into one’s lungs and lead to life-threatening pneumonia.

Flap that covers the trachea and prevents liquids from entering the lungs when swallowing.