10.5 Caring for Clients With Dementia

Dementia is a general term for loss of memory, language, problem-solving, and other thinking abilities that are severe enough to interfere with daily life. Disorders grouped under the general term “dementia” are caused by abnormal brain changes. These changes in brain cells affect their communication with each other, affecting a person’s thinking (i.e., cognitive abilities), behaviors, and feelings. There are many types of dementia. Alzheimer’s disease is the most common type of dementia. Vascular dementia is the second most common cause of dementia, followed by frontal-temporal dementia and Lewy body disease. While there are various causes of dementia, the observable characteristics are similar.[1]

Signs and symptoms of dementia include forgetfulness, impaired decision-making, and decreased thinking abilities that interfere with daily living. It is gradual and progressive, meaning the signs of dementia start out slowly and gradually get worse over time. Some examples of decreased thinking include changes in the ability to perform the following actions[2]:

- Recalling things from short-term memory

- Keeping track of a purse or wallet

- Paying bills

- Planning and preparing meals

- Remembering appointments

- Traveling out of the neighborhood

Dementia typically starts later in life, but it can begin as early as the mid-40s. It is not an expected part of aging. There is no cure for dementia, and the effects are irreversible. However, appropriate care improves the safety and the quality of life for individuals affected by dementia and their loved ones.[3]

Types of Dementia

Various types of dementia are further described in the following subsections.

Alzheimer’s Disease

About 10% of people older than 65 are affected by Alzheimer’s disease (AD). AD is the most common type of dementia and accounts for 60-80% of cases. Changes in the brain may begin a decade or more before impaired short-term memory and other cognitive problems appear, and the brain’s functioning continues to decline over time.

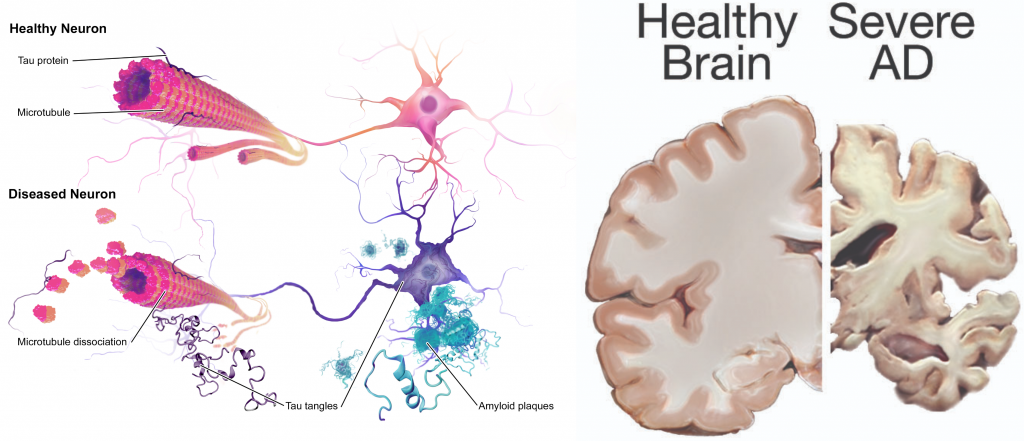

Scientists continue to unravel the complex brain changes involved in the onset and progression of AD. Abnormal deposits of proteins occur throughout the brain and form structures called amyloid plaques and tau tangles, causing previously healthy nerve cells (neurons) to stop functioning, lose connections with other neurons, and die. The damage initially appears to take place in the hippocampus and the cortex, the parts of the brain that are essential for forming memories. As additional neurons die, more parts of the brain are affected and begin to shrink. By the final stage of AD, damage is widespread, and brain tissue has shrunk significantly.[4] See Figure 10.6[5] for images comparing a healthy brain to the changes that occur during AD.

There is no single diagnostic test that can determine if a person has AD. Health care providers use a patient’s medical history, mental status tests, physical and neurological exams, and diagnostic tests to diagnose AD and other types of dementia. During the neurological exam, reflexes, coordination, muscle tone and strength, eye movement, speech, and sensation are tested. While there is no cure for AD, there are medications to reduce progression of the symptoms of memory loss and confusion, as well as interventions to manage common symptomatic behaviors.[6]

Vascular Dementia

Vascular dementia occurs at a younger age than Alzheimer’s disease with most symptoms starting around age 60. Vascular dementia is the second most common type of dementia worldwide and affects about 10-20% of patients with dementia. It is caused by microscopic bleeding and blood vessel blockage in the brain and is also called multi-infarct dementia. High blood pressure and strokes are common causes of vascular dementia.

The onset of vascular dementia is typically abrupt and followed by a rapid decline in functioning, in comparison to the slow progression of Alzheimer’s disease. Common symptoms in vascular dementia include apraxia and agnosia. Apraxia is the impaired ability to carry out motor activities despite intact motor function. This means the person can understand instructions and has the ability to complete an action but cannot process the cue to actually perform the task. Agnosia is the failure to recognize or identify objects despite intact sensory function.[7]

Lewy Body Dementia

Lewy body dementia (LBD) affects approximately 10 to 20% of patients with dementia. Like Alzheimer’s disease, LBD causes a progressive decline in cognition, leading to a functional impairment in daily activities. This type of dementia typically appears around age 70, and Parkinson’s disease and sleep disorders are often precursors to being diagnosed with LBD.

Significant features of LBD are fluctuating cognition, visual hallucinations, and sleep disturbances that affect motor and psychiatric functioning. These factors increase the risk of falls, infection, and malnutrition. Individuals with LBD frequently have aggressive behaviors. Medications used for treating dementia are less effective for LBD and often result in more adverse side effects than with other types of dementia.[8]

Frontotemporal Dementia

Frontotemporal dementia (FTD) is caused by degeneration of neurons in the frontal and anterior temporal lobes of the brain. In patients older than 65 years, it is the third most common cause of dementia. For individuals younger than 65 years, it is the second most common cause of early-onset dementia and commonly affects patients ranging from 45 to 65 years of age.

Genetics plays a key role in the development of FTD with approximately 40% of cases familial in origin. Head trauma and thyroid disease have also been linked to the development of FTD. Individuals who have experienced head trauma are three times more likely to develop FTD, and individuals with thyroid disease are over twice as likely to develop this type of dementia.

FTD targets brain areas that are responsible for personality, behavior, language learning, motivation, abstract thinking, and executive function. Behavior changes and/or language difficulties are common symptoms, followed by loss of cognitive abilities and executive functioning like planning, organizing, and self-control.[9]

Stages of Dementia

Stages of dementia are often classified as early, moderate, or advanced.

Early Dementia

There are ten symptoms of early dementia[10]:

- Memory loss that disrupts daily life. This type of memory loss refers to forgetting recently learned information that disrupts daily life, such as forgetting important dates or events, asking the same questions over and over, and increasingly needing to rely on memory aids (e.g., reminder notes or electronic devices). They often rely on family members for things they used to handle on their own. These impairments are different from typical age-related changes, like sometimes forgetting names or appointments but remembering them later.

- Challenges in planning or solving problems. This includes changes in an individual’s ability to develop and follow a plan or work with numbers. For example, they may have trouble following a familiar recipe or keeping track of monthly bills. They may have difficulty concentrating and take much longer to do things than they did before. This is more severe and frequent than typical age-related changes of making occasional errors when managing finances or household bills.

- Difficulty completing familiar tasks. This includes trouble driving to a familiar location, organizing a grocery list, or remembering the rules of a favorite game. This symptom is different from a typical age-related change of occasionally needing help to use microwave settings or to record a TV show.

- Confusion with time or place. This includes losing track of dates, seasons, and the passage of time. Individuals may have trouble understanding something if it is not happening immediately. Sometimes they may forget where they are or how they got there. This symptom is different from a typical age-related change of forgetting the date or day of the week but figuring it out later.

- Trouble understanding visual images and spatial relationships. Vision problems that include difficulty judging distance, determining color or contrast, or causing issues with balance or driving can be symptoms of Alzheimer’s disease. This is different from typical age-related visual changes. (See the Chapter 9.7, “Visual Impairment” subsection for more information on common vision problems.)

- New problems with words in speaking or writing. Individuals with Alzheimer’s disease may have trouble following or joining a conversation. They may stop in the middle of a conversation and have no idea how to continue or they may repeat themselves. They may struggle with vocabulary, have trouble naming a familiar object, or use the wrong name (e.g., calling a “watch” a “hand-clock”). This is different from a typical age-related change of having trouble finding the right word.

- Misplacing things and losing the ability to retrace steps. A person with Alzheimer’s disease may put things in unusual places. They may lose things and be unable to go back over their steps to find them again. They may accuse others of stealing, especially as the disease progresses. This is different from a typical age-related change of misplacing things from time to time and retracing steps to find them.

- Decreased or poor judgment. Individuals with Alzheimer’s disease may experience changes in judgment or decision-making. For example, they may use poor judgment when dealing with money or pay less attention to grooming or keeping themselves clean. This is different from a typical age-related change of making a bad decision or mistake once in a while, like neglecting to change the oil in the car.

- Withdrawal from work or social activities. A person living with Alzheimer’s disease may experience changes in the ability to hold or follow a conversation. As a result, they may withdraw from hobbies, social activities, or other engagements. They may have trouble keeping up with a favorite team or activity. This is different from a typical age-related change of sometimes feeling uninterested in family or social obligations.

- Changes in mood and personality. Individuals living with Alzheimer’s disease may experience mood and personality changes. They can become confused, suspicious, depressed, fearful, or anxious. They may be easily upset at home, with friends, or when out of their comfort zone. This is different from a typical age-related change of developing very specific ways of doing things and becoming irritable when a routine is disrupted.

Moderate Dementia

In moderate stages of dementia, people may experience the following symptoms[11]:

- Needing additional assistance with reminders to eat, wash, and use the restroom.

- Needing help in recognizing family and friends. Sometimes showing a photo of the person at a younger age will trigger their remaining long-term memory of that person.

- Wandering, getting lost, hallucinations, delusions, and repetitive behavior.

- Perseverating on a task, meaning they repeat something over and over. The person feels compelled to do something, such as call a family member, get groceries, or pick up their children. It often is linked to a responsibility they had as a younger person before memory impairment occurred.

- Hoarding of everyday objects. In a facility, this could be things like sugar or ketchup packets, straws, or salt and pepper shakers.

- Rummaging through items in drawers. This can be upsetting to others in a facility as the person may likely go into other residents’ rooms, not realizing it is inappropriate.

- Engaging in risky behavior, such as leaving the house in clothing inappropriate for weather conditions or leaving the stove burners on. If living in a facility, individuals may try to leave when it is not safe to do so (referred to as eloping).

- Demonstrating restlessness, agitation, irritability, or confusion that can begin or worsen as daylight begins to fade. This is referred to as sundowning. (Sundowning will be covered in more detail in the “Managing Sundowning” discussion later this section.)

In the moderate stage of dementia, people who pace or wander may not feel comfortable sitting down for a meal. Finger foods, frequent healthy snacks, and nutritionally enriched beverages can be offered to help maintain their nutritional intake.

Advanced Dementia

Those with advanced dementia may experience the following symptoms[12]:

- Urinary and/or bowel incontinence.

- Increasing need for assistance in washing, dressing, eating, and toileting.

- Unsteady gait or shuffling while walking, progressing to the inability to walk.

- Increased aggressive behavior, disinhibition (inappropriately acting on sexual desires), or inappropriate laughing.

- Difficulty eating, swallowing, and speaking.

- Increased time for processing conversations and following directions, progressing to unresponsiveness.

- Modified diet such as thickened fluids and a soft or pureed diet.

- Seizures may develop in advanced stages.

To learn more about how Alzheimer’s changes the brain, view the following YouTube video[13]: How Alzheimer’s Changes the Brain.

Caring for Individuals With Dementia

As dementia progresses and cognition continues to deteriorate, care must be individualized to meet the needs of the patient and family. Providing patient safety and maintaining quality of life while meeting physical and psychosocial needs are important aspects of nursing care. Unsafe behaviors put individuals with dementia at increased risk for injury.[14]

Similar to those with intellectual disabilities, individuals with dementia can be very physically mobile. Their decreased awareness of safety paired with good physical mobility means they require constant oversight as the disease progresses. Disruptive behaviors often occur due to the patient having a need or emotion without the ability to express it due to the changes in their brain. These needs may be untreated pain, hunger, anxiety, or the need to use the bathroom. Without the ability to communicate these needs, the individual may display agitation, aggression, shouting, combativeness, and many other behaviors that can be distressing for all involved. The patient’s family members and caregivers require education and support to recognize that behaviors are a symptom of dementia and/or a communication of their needs rather than being upset with the caregiver. As a nursing assistant, the more familiar you are with a client, the easier it becomes to understand their behaviors and provide activities to keep their emotions stable while proactively meeting their care needs.[15]

Providing Validation Therapy

Caring for individuals with dementia can be difficult, especially for family members who have trouble understanding what is happening to their loved one. They may try to reorient the person to the present time and situation, which can be frustrating for a person with dementia because they are unable to process these cues.

One of the most effective methods used to assist people with dementia is called validation therapy, meaning you support the reality the person with dementia is experiencing and do not attempt to reorient them. Begin by determining what the person is perseverating on and figure out a way to satisfy their need or respond to their emotion. For example, if a person with dementia is perseverating on the need to catch an imagined bus, you can sit with them by a window and tell them you will have a conversation until the bus arrives. If they are looking for a child they recall from their past experiences, allow them to hold a doll or call the “child” they are looking for on the phone. After they feel their concerns are validated, it will be easier to redirect them to another activity and reduce their emotional response.

Remember that individuals with dementia still retain long-term memories, and these memories often provide comfort and ease anxiety. It is helpful to provide activities similar to those they formerly enjoyed or simulate situations that resemble their prior work or home environment. For example, if a person was a homemaker, allow them to fold laundry or towels. If they enjoyed working with their hands, provide nuts and bolts to put together and take apart. If they worked in an office, folding letters and placing them in envelopes may be helpful. Activities like sorting cards, doing simple crafts, or baking may also be enjoyable. In the early to moderate stages of dementia, ambulation, chair exercises, or range of motion exercises can help to utilize pent-up energy that can otherwise lead to agitation.

Keeping the environment similar to their previous home can also be a calming factor by helping them recognize where their room is and reducing wandering or the risk of entering a room that does not belong to them. Some care facilities paint the doorframe like the resident’s home, use plates and utensils from the resident’s kitchen, and bring furniture from their home as well.

The “Dementia Village” is an entire neighborhood in Holland, complete with movie theater, restaurants, and stores and all staffed with specialized dementia caregivers. The neighborhood is enclosed, allowing residents to walk on their own without the risk of wandering and getting lost or risking safety. View the following YouTube video about how this community is set up[16]: CNN’s World’s Untold Stories: Dementia Village.

Managing Sundowning

Sundowning refers to restlessness, agitation, irritability, or confusion that typically begins or worsens as daylight begins to fade and can continue into the night, making it difficult for patients with dementia to sleep. Being overtired can increase late-afternoon and early-evening restlessness. Tips to manage sundowning are as follows[17]:

- Take the resident outside or expose them to bright light in the morning to reset their circadian rhythm.

- Do not plan too many activities during the day. A full schedule can be overtiring.

- Make early evening a quiet time of day. Play soothing music or ask a family member or friend to call during this time.

- Close the curtains or blinds at dusk to minimize shadows and the confusion they may cause.

- Reduce noise, clutter, or the number of people in the room.

- Do not serve coffee, cola, or other drinks with caffeine late in the day.

Managing Aggressive Behaviors

Aggressive behaviors may be verbal or physical. They can occur suddenly, with no apparent reason, or result from a frustrating situation. While aggression can be hard to cope with, understanding this is a symptom of dementia and the person with dementia is not acting this way on purpose can help caregivers respond.[18] See Figure 10.7[19] for an image of a resident with dementia demonstrating aggressive verbal behavior.

There are many therapeutic methods for a nurse or caregiver to initially respond to aggressive behaviors displayed by a person with dementia as previously described in the “Caring for Clients With Mental Health or Substance Use Disorders” section:

- Communication

- Routine

- Empathy

- Redirect or reapproach

Aggression can be caused by many factors including physical discomfort, environmental factors, and poor communication. If a person with dementia becomes aggressive, consider what might be contributing to the change in behavior and address it.[20]

Physical Discomfort

- Is the person able to let you know that they are experiencing physical pain? It is not uncommon for people with dementia to have urinary tract or other infections. Due to their loss of cognitive function, they are unable to articulate or identify the cause of physical discomfort and, therefore, may express it through physical aggression.

- Is the person tired because of inadequate rest or sleep?

- Is the person hungry or thirsty?

- Are medications causing side effects? Side effects are especially likely to occur when individuals are taking multiple medications for several health conditions.[21]

Environmental Factors

- Is the person overstimulated by loud noises, an overactive environment, or physical clutter? Large crowds or being surrounded by unfamiliar people – even within one’s own home – can be overstimulating for a person with dementia.

- Does the person feel lost?

- What time of day is the person most alert? Most people function better during a certain time of day; typically, mornings are best. Consider the time of day when making appointments or scheduling activities. Choose a time when you know the person is most alert and best able to process new information or surroundings.[22]

Poor Communication

- Are your instructions simple and easy to understand?

- Use simple language.

- Limit choices to one or two options. (Example: “Do you want to wear the blue shirt or the black shirt?”)

- Be sure communication techniques take sensory deficits into consideration.

- Try physically demonstrating instead of verbally instructing; use pictures or gestures.

- Are you asking too many questions or making too many statements at once? Give ample time to process and respond.

- Is the person picking up on your own stress or irritability? Take a moment for deep breathing or ask another caregiver to assist if available.[23]

Other Techniques

The following techniques are additional strategies that can be used with aggressive behavior[24]:

- Begin by trying to identify the immediate cause of the behavior. Think about what happened right before the reaction that may have triggered the behavior. Rule out pain as the cause of the behavior. Pain can trigger aggressive behavior for a person with dementia.

- Focus on the person’s feelings, not the facts. Look for the feelings behind the specific words or actions.

- Try not to get upset. Be positive and reassuring and speak slowly in a soft tone and seek help from another caregiver if needed.

- Limit distractions. Examine the person’s surroundings and adapt them to avoid future triggers.

- Implement a relaxing activity. Try music, massage, or exercise to help soothe the person.

- Shift the focus to another activity (redirect). The immediate situation or activity may have unintentionally caused the aggressive response, so try a different approach.

- Take a break if needed. If the person is in a safe environment and you are able, walk away and take a moment for emotions to cool.

- Ensure safety! Make sure you and the patient are safe. Be aware of movement of the patient’s hands and feet and protect yourself from being hit or kicked. Avoid potential strangulation hazards like retractable lanyards. If interventions do not successfully calm down an aggressive patient, seek assistance from other staff members. If it is an emergency situation, call 911 and be sure to tell the responders the person has dementia that is causing them to act aggressively.

Responding to a Person Having Hallucinations

When responding to a person experiencing hallucinations, be cautious. First, assess the situation and determine whether the hallucination is a problem for the person or for you. Is the hallucination upsetting? Is it leading the person to do something dangerous? Is the sight of an unfamiliar face causing the person to become frightened? If so, react calmly and quickly with reassuring words and a comforting touch. Do not argue with the person about what they see or hear. If the behavior is not dangerous, there may not be a need to intervene. Utilize aspects of validation therapy by doing the following[25]:

- Offer reassurance. Respond in a calm, supportive manner. You may want to respond with, “Don’t worry. I’m here. I’ll protect you. I’ll take care of you.” Gentle patting may turn the person’s attention toward you and reduce the hallucination.

- Acknowledge the feelings behind the hallucination and try to find out what the hallucination means to the individual. You might want to say, “It sounds as if you’re worried,” or “This must be frightening for you.”

- Use distractions. Suggest a walk or move to another room. Frightening hallucinations often subside in well-lit areas where other people are present. Try to turn the person’s attention to music, conversation, or activities they enjoy.

- Respond honestly. If the person asks you about a hallucination or delusion, be honest. For example, if they ask, “Do you see the spider on the wall?,” you can respond, “I know you see something, but I don’t see it.” This way you’re not denying what the person sees or hears and avoiding escalating their agitation.

- Modify the environment. Check for sounds that might be misinterpreted, such as noise from a television or an air conditioner. Look for lighting that casts shadows, reflections, or distortions on the surfaces of floors, walls, and furniture. Turn on lights to reduce shadows. Cover mirrors with a cloth or remove them if the person thinks they are looking at a stranger.

Managing Wandering

Wandering is the simple act of a person walking around with no purpose due to confusion regarding their location or environment. It can occur in any stage of dementia. Wandering can be unsafe if the person should not be ambulating independently or if they are attempting to leave home or a facility resulting in them becoming lost without supervision. It is especially risky during cold winter months when there is the potential for hypothermia because the person won’t realize their need for warm clothing or to return indoors.

Offering opportunities for exercise or other physical movement (like range of motion exercises) several times throughout the day can reduce the urgency for people to move about unsafely. If the person does not want to participate in physical movement, any engaging experiences such as sorting items, arts and crafts, baking, or folding clothes can help to keep residents safe.

A possible intervention for wandering is a device called a wanderguard. This device is a bracelet that has a tracking device. The wanderguard can be worn on the wrist or ankle. Some facilities place the wanderguard on a resident’s walker or wheelchair; however, by choosing either of these locations, the wanderguard is only effective when the resident is using that particular device. The wanderguard allows the location of the person wearing it to be monitored via an app on a phone or other device such as a tablet or laptop. Multiple wanderguards can be activated and monitored at the same time on one device. The wanderguard sounds an alarm when the wearer comes into close proximity with any exits such as elevators, doors, and windows. It may also initiate locking of doors and disabling of elevator buttons to assist in keeping residents safe. See Figure 10.8[26] for an image of a wanderguard placed on a resident’s wrist.

- Alzheimer's Association. (n.d.). What is dementia? https://www.alz.org/alzheimers-dementia/what-is-dementia?utm_source=google&utm_medium=paidsearch&utm_campaign=google_grants&utm_content=dementia&gclid=Cj0KCQjwvqeUBhCBARIsAOdt45Z-WN2Wk5Tw07mB7PRGJ3axLWBDxeaooRqavb7_E7n3wQacrGvghdwaAqoXEALw_wcB ↵

- Alzheimer's Association. (n.d.). What is dementia? https://www.alz.org/alzheimers-dementia/what-is-dementia?utm_source=google&utm_medium=paidsearch&utm_campaign=google_grants&utm_content=dementia&gclid=Cj0KCQjwvqeUBhCBARIsAOdt45Z-WN2Wk5Tw07mB7PRGJ3axLWBDxeaooRqavb7_E7n3wQacrGvghdwaAqoXEALw_wcB ↵

- This work is a derivative of Nursing Fundamentals by Chippewa Valley Technical College and is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- This work is a derivative of Nursing Fundamentals by Chippewa Valley Technical College and is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- “Alzheimers_Disease.jpg” by BruceBlaus is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0 and “24239522109_6b061a9d69_o.jpg” by NIH Image Gallery is licensed under CC0 ↵

- This work is a derivative of Nursing Fundamentals by Chippewa Valley Technical College and is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- Abnormal Psychology by Lumen Learning is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- This work is a derivative of A Long Goodbye: Ed and Mary’s Journey With Lewy Body Dementia by James Cook University and is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 ↵

- This work is a derivative of StatPearls by Khan and De Jesus and is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- Alzheimer's Association. (n.d.). What is dementia? https://www.alz.org/alzheimers-dementia/what-is-dementia?utm_source=google&utm_medium=paidsearch&utm_campaign=google_grants&utm_content=dementia&gclid=Cj0KCQjwvqeUBhCBARIsAOdt45Z-WN2Wk5Tw07mB7PRGJ3axLWBDxeaooRqavb7_E7n3wQacrGvghdwaAqoXEALw_wcB ↵

- This work is a derivative of Nursing Fundamentals by Chippewa Valley Technical College and is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- This work is a derivative of Nursing Fundamentals by Chippewa Valley Technical College and is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- National Institute on Aging. (2017, August 23). How Alzheimer's changes the brain [Video]. YouTube. All rights reserved. https://youtu.be/0GXv3mHs9AU ↵

- Alzheimer's Association. (n.d.). What is dementia? https://www.alz.org/alzheimers-dementia/what-is-dementia?utm_source=google&utm_medium=paidsearch&utm_campaign=google_grants&utm_content=dementia&gclid=Cj0KCQjwvqeUBhCBARIsAOdt45Z-WN2Wk5Tw07mB7PRGJ3axLWBDxeaooRqavb7_E7n3wQacrGvghdwaAqoXEALw_wcB ↵

- Alzheimer's Association. (n.d.). What is dementia? https://www.alz.org/alzheimers-dementia/what-is-dementia?utm_source=google&utm_medium=paidsearch&utm_campaign=google_grants&utm_content=dementia&gclid=Cj0KCQjwvqeUBhCBARIsAOdt45Z-WN2Wk5Tw07mB7PRGJ3axLWBDxeaooRqavb7_E7n3wQacrGvghdwaAqoXEALw_wcB ↵

- CNN. (2013, July 10). CNN’s world’s untold stories: Dementia village [Video]. YouTube. All rights reserved. https://youtu.be/jwt4uGYGGUA ↵

- This work is a derivative of Nursing Fundamentals by Chippewa Valley Technical College and is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- This work is a derivative of Nursing Fundamentals by Chippewa Valley Technical College and is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- “5012292106_507e008c7a_o.jpg” by borosjuli is licensed under CC BY 2.0 ↵

- Alzheimer's Association. (n.d.). What is dementia? https://www.alz.org/alzheimers-dementia/what-is-dementia?utm_source=google&utm_medium=paidsearch&utm_campaign=google_grants&utm_content=dementia&gclid=Cj0KCQjwvqeUBhCBARIsAOdt45Z-WN2Wk5Tw07mB7PRGJ3axLWBDxeaooRqavb7_E7n3wQacrGvghdwaAqoXEALw_wcB ↵

- Alzheimer's Association. (n.d.). What is dementia? https://www.alz.org/alzheimers-dementia/what-is-dementia?utm_source=google&utm_medium=paidsearch&utm_campaign=google_grants&utm_content=dementia&gclid=Cj0KCQjwvqeUBhCBARIsAOdt45Z-WN2Wk5Tw07mB7PRGJ3axLWBDxeaooRqavb7_E7n3wQacrGvghdwaAqoXEALw_wcB ↵

- Alzheimer's Association. (n.d.). What is dementia? https://www.alz.org/alzheimers-dementia/what-is-dementia?utm_source=google&utm_medium=paidsearch&utm_campaign=google_grants&utm_content=dementia&gclid=Cj0KCQjwvqeUBhCBARIsAOdt45Z-WN2Wk5Tw07mB7PRGJ3axLWBDxeaooRqavb7_E7n3wQacrGvghdwaAqoXEALw_wcB ↵

- Alzheimer's Association. (n.d.). What is dementia? https://www.alz.org/alzheimers-dementia/what-is-dementia?utm_source=google&utm_medium=paidsearch&utm_campaign=google_grants&utm_content=dementia&gclid=Cj0KCQjwvqeUBhCBARIsAOdt45Z-WN2Wk5Tw07mB7PRGJ3axLWBDxeaooRqavb7_E7n3wQacrGvghdwaAqoXEALw_wcB ↵

- This work is a derivative of Nursing Fundamentals by Chippewa Valley Technical College and is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- Alzheimer's Association. (n.d.). What is dementia? https://www.alz.org/alzheimers-dementia/what-is-dementia?utm_source=google&utm_medium=paidsearch&utm_campaign=google_grants&utm_content=dementia&gclid=Cj0KCQjwvqeUBhCBARIsAOdt45Z-WN2Wk5Tw07mB7PRGJ3axLWBDxeaooRqavb7_E7n3wQacrGvghdwaAqoXEALw_wcB ↵

- "wanderguard-blue-tag-2.jpg" by unknown author is included on the basis of Fair Use. Access original image at https://www.stanleyhealthcare.com/products/wanderguard-blue-bracelet. ↵

A general term for loss of memory, language, problem-solving, and other thinking abilities that are severe enough to interfere with daily life.

The impaired ability to carry out motor activities despite intact motor function.

The failure to recognize or identify objects despite intact sensory function.

The act of repeating a task or thought over and over.

A method of therapeutic communication used to connect with someone who has moderate - to late-stage dementia and avoid agitation.

Restlessness, agitation, irritability, or confusion that typically begins or worsens as daylight begins to fade and can continue into the night.

Walking around with no purpose due to their confusion regarding their location or environment.

A device worn on the wrist or ankle that can assist with tracking an individual's movements.