4.4 Precautions Used to Prevent the Spread of Infection

Health care agencies use several methods to prevent the spread of infection: standard precautions and transmission-based precautions.

Standard Precautions

Standard precautions are used by health care workers during client care when contact or potential contact with blood or body fluids may occur. Standard precautions should also be used when assisting a client with activities of daily living (ADLs) and using water, soap, or lotion. Standard precautions are based on the principle that all blood, body fluids (except sweat), nonintact skin, and mucous membranes may contain transmissible infectious agents. These precautions reduce the risk of exposure for the health care worker and protect patients from potential transmission of infectious organisms.[1]

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), standard precautions include the following[2]:

- Using proper hand hygiene at the appropriate times

- Using personal protective equipment (e.g., gloves, gowns, masks, eyewear) whenever exposure to infectious agents may occur

- Implementing respiratory hygiene for staff, patients, and visitors

- Proper cleaning and sanitizing of the environment, equipment, and devices

- Handling laundry safely

- Using transmission-based precautions when indicated

Hand Hygiene

The easiest and most effective way to break the chain of infection is by using proper hand hygiene at appropriate times during patient care. Knowing when to wash your hands, how to properly wash your hands, and when to use soap and water or hand sanitizer are vital for reducing the spread of infection and keeping yourself healthy. Hand hygiene is the process of removing, killing, or destroying microorganisms or visible contaminants from the hands. There are two hand-hygiene techniques: handwashing with soap and water and the use of alcohol-based hand rub (ABHR), also referred to as hand hygiene gel or hand sanitizer.[3]

Health care providers’ hands are the most common mode of transmission of microorganisms. As a nursing assistant, your hands will touch many people and objects when providing care. When you touch a client, their personal items, medical equipment, or their surrounding environment, you can indirectly transmit microorganisms to the client, another client, yourself, equipment, or a new environment. Microorganisms can easily be transferred from your hands to others or objects in the health care setting if proper hand hygiene practices are not followed. Consistent and effective hand hygiene is vital for breaking the chain of transmission.[4]

It is essential for all health care workers to use proper hand hygiene during specific moments of patient care[5]:

- Immediately before touching a patient

- Before performing an aseptic task, such as emptying urine from a Foley catheter bag

- Before moving from a soiled body site to a clean body site

- After touching a patient or their immediate environment

- After contact with blood, body fluids, or contaminated surfaces (with or without gloves)

- Immediately after glove removal

See Figure 4.4[6] for an illustration of the five moments of hand hygiene.

Hand hygiene also includes health care workers keeping their nails short with tips less than 0.5 inches and no nail polish. Nails should be natural, and artificial nails or tips should not be worn. Artificial nails and chipped nail polish have been associated with a higher level of pathogens carried on the hands of health care workers despite using proper hand hygiene.[7]

Review the Moments of Hand Hygiene by clicking on the interactive activity below.

This work is a derivative of Your 4 Moments for Hand Hygiene by Michelle Hughes and is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

Proper hand hygiene includes handwashing with soap and water or the use of alcohol-based hand rub. Both procedures are described in the following sections.

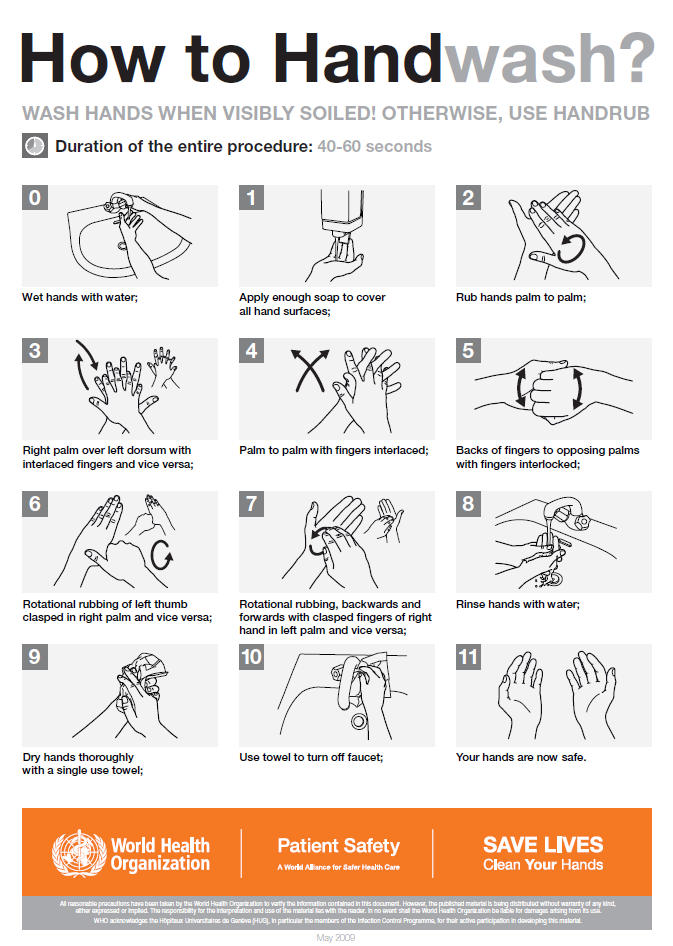

Handwashing With Soap and Water

Handwashing involves the use of soap and water to physically remove microorganisms from one’s hands. Certain health care situations require handwashing with soap and water instead of using alcohol-based hand rub (ABHR). For example, hands must be washed with soap and water if they are visibly soiled, have been exposed to blood or body fluids, or have been exposed to norovirus, C. difficile, or Bacillus anthracis. The mechanical action of lathering and scrubbing with soap for a minimum of 20 seconds is vital for removing these types of microorganisms.[8]

Soap is required during handwashing to dissolve fatty materials and facilitate their subsequent flushing and rinsing with water. Soap must be rubbed on all surfaces of both hands followed by thorough rinsing and drying. Water alone is not suitable for cleaning soiled hands. The entire procedure should last 40 to 60 seconds, and soap approved by the health agency should be used.[9]

When washing with soap and water, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recommends the following steps[10]:

- Wet hands with warm or cold running water and apply facility-approved soap.

- Lather hands by rubbing them together with the soap. Use the same technique as the hand rub process to clean the palms and fingers, between the fingers, the backs of the hands and fingers, the fingertips, and the thumbs.

- Scrub thoroughly for at least 20 seconds.

- Rinse hands well under clean, running water.

- Dry the hands, using a clean towel or disposable toweling, from fingers to wrists.

- Use a clean paper towel to shut off the faucet.

See Figure 4.5[11] for an illustration of handwashing with soap and water.

See the “Skills Checklist: Hand Hygiene With Soap and Water” section later in this chapter for a checklist of steps and an associated demonstration video of this procedure. Common safety considerations and errors when washing hands are described in the following box.

Safety Considerations[12]

- Always wash hands with soap and water if hands are visibly soiled.

- When working with clients where C. difficile, norovirus, or Bacillus anthracis is suspected or confirmed, soap and water must be used. It is more effective in physically removing the C. difficile spores compared to ABHR, which is not as effective at penetrating the spores.

- Friction and rubbing are required to remove transient bacteria, oil, and debris from hands.

- Always use soap and water if hands are exposed to blood, body fluids, or other body substances.

- Multistep rubbing techniques using soap and water are required to promote coverage of all surfaces on hands.

Common Errors When Washing Hands With Soap and Water[13]

- Not using enough soap to cover all surfaces of the hands and wrists.

- Not using friction when washing hands.

- Not washing hands long enough. The mechanical action of lathering and scrubbing should be a minimum of 20 seconds, and the entire procedure should last 40 to 60 seconds.

- Missing areas such as the fingernails, wrists, backs of hands, and thumbs.

- Not removing all soap from hands and wrists.

- Shaking water off hands.

- Not thoroughly drying the hands.

- Drying hands from wrists to fingers or in both directions.

Practice your knowledge by clicking on this interactive learning activity.

This work is a derivative of the YouTube Hand Washing Video by Michelle Hughes and is licensed under CC BY-NC 4.0.

Alcohol-Based Hand Rub

When performing hand hygiene using the alcohol-based hand rub (ABHR) technique, a liquid, gel, or foam alcohol-based solution is used. ABHR is the preferred method for hand hygiene when soap and water handwashing is not required. It reduces the number of transient microorganisms on hands and is more effective for preventing healthcare-acquired infections (HAIs) caused by Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) and Vancomycin-resistant enterococcus (VRE). Hand hygiene with ABHR should be performed in front of the client prior to the beginning of care and at the end of the interaction. ABHR provided by the agency should be used with a 70–90% alcohol concentration.[14]

The benefits of ABHR include the following[15]:

- It kills the majority of microorganisms (including viruses) from hands.

- It requires less time than soap and water handwashing.

- It provides better skin tolerability and reduces skin irritation because it contains emollients.

- It is easy to use and available at the point of care (i.e., where three elements of the client, the health care provider, and care involving the client occur together).

Read safety considerations and common errors when using ABHR in the following box. See the “Skills Checklist: Hand Hygiene With Alcohol-Based Hand Sanitizer” section later in this chapter for a checklist of steps and an associated demonstration video of this procedure.

Safety Considerations[16]

- Do not use ABHR in combination with soap and water because it may increase skin irritation.

- Use ABHR that contains emollients (oils) to help reduce skin irritation and overdrying.

- Allow hands to dry completely before initiating tasks (e.g., touching the client or the environment or applying clean gloves).

- Use ABHR for all moments of hand hygiene if soap and water are not required.

- DO NOT use ABHR if hands are visibly soiled, have been exposed to blood or body fluids, or the client is suspected to have C. difficile, norovirus, or Bacillus anthracis.

- Only use ABHR supplied by the facility.

Common Errors When Performing an ABHR[17]

- Not letting hands air dry (for example, rubbing one’s hands on pants to dry it off).

- Shaking hands to dry.

- Applying too much alcohol-based solution.

- Not applying enough alcohol-based solution.

- Not rubbing hands long enough (a minimum of 20 seconds) and until hands are dry.

- Missing areas such as the fingernails, wrists, backs of the hands, and thumbs.

Practice your knowledge by clicking on this interactive learning activity.

This work is a derivative of Performing an Alcohol-Based Hand Rub by Michelle Hughes and is licensed under CC BY-NC 4.0.

Respiratory Hygiene and Other Hygienic Practices

Respiratory hygiene should be used by any person with signs of illness, including cough, congestion, or increased production of respiratory secretions to prevent the spread of infection. Respiratory hygiene refers to coughing or sneezing into the inside of one’s elbow or covering one’s mouth/nose with a tissue when coughing and promptly disposing of used tissues. Hand hygiene should be immediately performed after contact with one’s respiratory secretions. A coughing person should also wear a surgical mask to contain secretions.[18]

Additional hygiene measures are also used to prevent the spread of infection. For example, regularly changing bed linens, towels, and hospital gowns eliminates potential reservoirs of bacteria. Gripper socks should be removed before patients get into bed to prevent pathogens from the floor from being transferred to the patient’s bed linens.

Mobile devices should be cleaned regularly. Research has shown that cell phones and mobile devices carry many pathogens and are dirtier than a toilet seat or the bottom of a shoe. Patients, staff, and visitors routinely bring mobile devices into health care facilities that can cause the spread of infection. Mobile devices should be frequently wiped with disinfectant.

Disinfection and Sterilization

Disinfection and sterilization are procedures used to remove harmful pathogens from equipment and the environment to decrease the risk of spreading infection. Disinfection is the removal of microorganisms, but it does not destroy all spores and viruses. Sterilization destroys all pathogens on equipment or in the environment, including spores and viruses, and includes methods such as steam, boiling water, dry heat, radiation, and chemicals. Because of the harshness of sterilization methods, skin can only be disinfected and not sterilized.[19]

Asepsis refers to the absence of infectious material or infection. Surgical asepsis is the absence of all microorganisms during any type of invasive procedure, such as during surgery or heart catheterizations. Sterilization is performed on equipment used during invasive procedures. As a nursing assistant, you may assist a registered nurse during a procedure requiring sterile technique; however, performing sterile procedures independently is not in the scope of practice for nursing assistants.

In long-term care and other health care settings other than surgery, medical asepsis is used. Medical asepsis refers to techniques used to prevent the transfer of microorganisms from one person or object to another but do not eliminate all microorganisms. Nursing assistants implement medical asepsis in the following ways:

- Performing hand hygiene at the appropriate moments of patient care. (See previous Figure 4.4.)

- Using a barrier when placing clean linens, wash basins, and other items on a shared surface such as the countertop in a resident’s room.

- Pulling the privacy curtain when one resident has a droplet-transmitted infection to protect transmission to the other resident in a shared room.

- Cleaning equipment (such as blood pressure cuffs) between use on residents.

- Starting with “cleaner” areas of the body when assisting with care and then moving to areas with higher levels of microorganisms. For example, when bathing a client, the face is washed first, followed by the upper body and then finishing with perineal care. (Perineal care involves washing the genital and rectal areas of the body.)

Laundry

When handling dirty linens, textiles, and patients’ clothing, follow agency policy regarding transport to prevent the potential spread of infection. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) states that contaminated textiles and fabrics should be handled with minimal agitation to avoid contamination of air, surfaces, and other individuals. They should be bagged at the point of use, and leak-resistant bags should be used for textiles and fabrics contaminated with blood or body substances.[20]

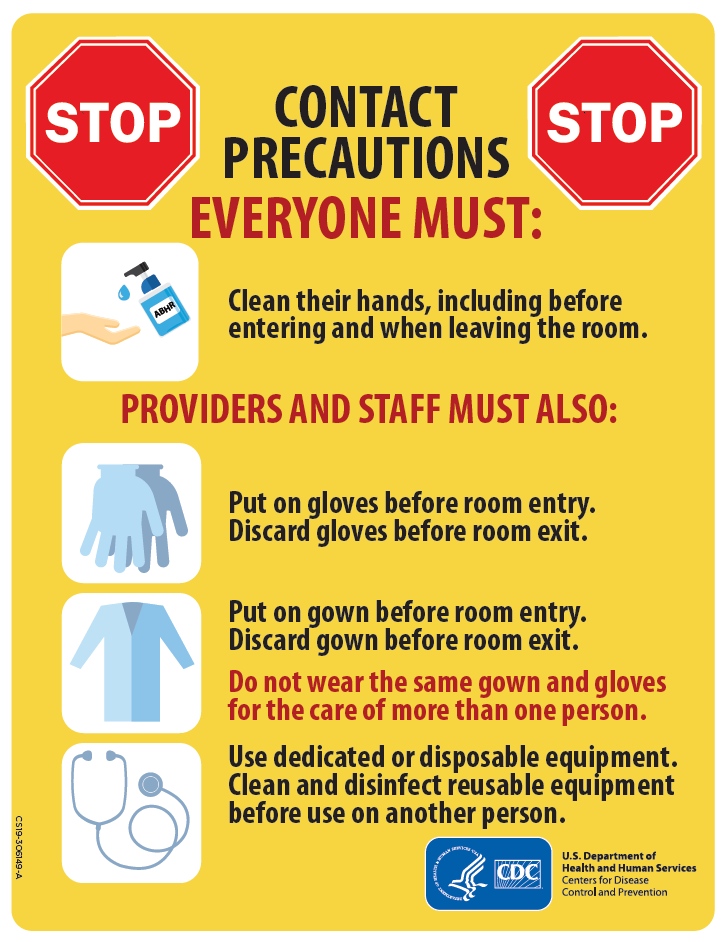

Transmission-Based Precautions

When providing care for individuals with known or suspected infections, additional precautions are used in addition to the previously discussed standard precautions. Certain types of pathogens and communicable diseases are easily transmitted to others and require additional precautions to interrupt the spread of infectious agents to health care workers and other clients. For example, Coronavirus disease (COVID-19), C. difficile (C-diff), Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA), Vancomycin-resistant enterococci (VRE), Respiratory Syncytial Virus (RSV), measles, and tuberculosis (TB) require transmission-based precautions.

Transmission-based precautions (commonly referred to as isolation precautions) use specific types of personal protective equipment (PPE) and practices based on the pathogen’s mode of transmission. It is vital for nursing assistants to understand what PPE should be used in specific client care situations, which is determined by the pathogen’s mode of transmission and their possible risk of exposure.[21] Transmission-based precautions include three categories: contact, droplet, and airborne precautions. Read more about each type of transmission-based precaution in Table 4.1.

Table 4.1 Categories of Transmission-Based Precautions[22],[23],[24]

| Transmission-Based Precaution | PPE Required | Special Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Contact | Gloves and gown, possibly face shield | Used for clients with known or suspected infections such as C-difficile (C-diff), methicillin-resistant staphylococcus aureus (MRSA), vancomycin resistant enterococcus (VRE), or norovirus transmitted by touch (e.g., drainage from wounds or fecal incontinence). Contact precautions should be used when there is expected contact with the source of the pathogen or any surfaces within the resident’s room. For example, MRSA in a client’s wound transmits with direct contact with the wound, so wearing gloves and a gown when entering the room with a meal tray is typically sufficient. However, MRSA in a client’s urine could be accidentally splashed onto one’s mucous membrane when emptying the bag of an indwelling urinary catheter, so a face shield is also necessary for this task, in addition to wearing gloves and a gown. |

| Droplet | Gloves and a mask | Used for clients with a diagnosed or suspected pathogen that is spread in small droplets from sneezing or other oral and nasal secretions, such as influenza or pertussis. Droplets can travel six feet, so using barriers such as privacy curtains and closing doors can also prevent the spread of infection to others. |

| Airborne | Gloves and respirator | Used for clients with diagnosed or suspected pathogens spread by very small airborne particles from nasal and oral secretions that can float long distances through the air, such as measles and tuberculosis. Respirators are specially designed masks that fit closely on the face and filter out small particles, including the virus that causes COVID. Clients must be placed in a room with specialized air handling equipment found in doctors’ offices and hospitals. Residents in long-term care settings suspected of having an airborne illness should be transferred immediately to prevent the spread of infection to other residents. |

Signage for Transmission-Based Precautions

When a resident has an infectious illness requiring transmission-based precautions, a sign is placed on their door and a cart of PPE supplies is placed nearby. Signs vary by facility but look similar to the image in Figure 4.6.[25] Due to HIPAA regulations, the type of the pathogen and the source cannot be displayed publicly, so the sign instructs anyone wishing to enter the room to ask the nurse first. Additional information regarding the type and source of the infection can be found in the client’s nursing care plan. After you become aware of the pathogen, the source, and the required PPE, you can safely enter the room. If you are unsure about any aspect of PPE required or your risk of exposure, talk to the nurse before entering the room or providing care.

View the following YouTube video from the University of Iowa about isolation precautions in a health care setting: Standard and Isolation Precautions.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2016, January 26). Standard precautions for all patient care. https://www.cdc.gov/infectioncontrol/basics/standard-precautions.html ↵

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2016, January 26). Standard precautions for all patient care. https://www.cdc.gov/infectioncontrol/basics/standard-precautions.html ↵

- This work is a derivative of Introduction to Infection Prevention and Control Practices for the Interprofessional Learner by Hughes, Kenmir, St-Amant, Cosgrove, & Sharpe and is licensed under CC BY-NC 4.0 ↵

- This work is a derivative of Introduction to Infection Prevention and Control Practices for the Interprofessional Learner by Hughes, Kenmir, St-Amant, Cosgrove, & Sharpe and is licensed under CC BY-NC 4.0 ↵

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2019, April 29). Hand hygiene in healthcare settings. https://www.cdc.gov/handhygiene/ ↵

- “5Moments_Image.gif” by World Health Organization is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO. Access for free at https://www.who.int/infection-prevention/campaigns/clean-hands/5moments/en/ ↵

- Blackburn, L., Acree, K., Bartley, J., DiGiannantoni, E., Renner, E., & Sinnott, L. T. (2020). Microbial growth on the nails of direct patient care nurses wearing nail polish. Oncology Nursing Forum, 47(2), 155-164. https://doi.org/10.1188/20.onf.155-164 ↵

- This work is a derivative of Introduction to Infection Prevention and Control Practices for the Interprofessional Learner by Hughes, Kenmir, St-Amant, Cosgrove, & Sharpe and is licensed under CC BY-NC 4.0 ↵

- This work is a derivative of Introduction to Infection Prevention and Control Practices for the Interprofessional Learner by Hughes, Kenmir, St-Amant, Cosgrove, & Sharpe and is licensed under CC BY-NC 4.0 ↵

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2016, January 26). Standard precautions for all patient care. https://www.cdc.gov/infectioncontrol/basics/standard-precautions.html ↵

- “How_To_HandWash_Poster.pdf” by World Health Organization is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO. Access for free at https://www.who.int/infection-prevention/campaigns/clean-hands/5moments/en/ ↵

- This work is a derivative of Introduction to Infection Prevention and Control Practices for the Interprofessional Learner by Hughes, Kenmir, St-Amant, Cosgrove, & Sharpe and is licensed under CC BY-NC 4.0 ↵

- This work is a derivative of Introduction to Infection Prevention and Control Practices for the Interprofessional Learner by Hughes, Kenmir, St-Amant, Cosgrove, & Sharpe and is licensed under CC BY-NC 4.0 ↵

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2016, January 26). Standard precautions for all patient care. https://www.cdc.gov/infectioncontrol/basics/standard-precautions.html ↵

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2016, January 26). Standard precautions for all patient care. https://www.cdc.gov/infectioncontrol/basics/standard-precautions.html ↵

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2016, January 26). Standard precautions for all patient care. https://www.cdc.gov/infectioncontrol/basics/standard-precautions.html ↵

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2016, January 26). Standard precautions for all patient care. https://www.cdc.gov/infectioncontrol/basics/standard-precautions.html ↵

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2016, January 26). Standard precautions for all patient care. https://www.cdc.gov/infectioncontrol/basics/standard-precautions.html ↵

- This work is a derivative of Nursing Fundamentals by Chippewa Valley Technical College and is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2020, April 29). Infection control. https://www.cdc.gov/infectioncontrol/index.html ↵

- This work is a derivative of Introduction to Infection Prevention and Control Practices for the Interprofessional Learner by Hughes, Kenmir, St-Amant, Cosgrove, & Sharpe and is licensed under CC BY-NC 4.0 ↵

- Office of Infectious Disease and HIV/AIDS Policy. (n.d.). Health care-associated infections. U.S. Department of Health & Human Services. https://www.hhs.gov/oidp/topics/health-care-associated-infections/index.html ↵

- This work is a derivative of Introduction to Infection Prevention and Control Practices for the Interprofessional Learner by Hughes, Kenmir, St-Amant, Cosgrove, & Sharpe and is licensed under CC BY-NC 4.0 ↵

- Siegel, J. D., Rhinehart, E., Jackson, M., Chiarello, L., & Healthcare Infection Control Practices Advisory Committee. (2019, July 22). 2007 guideline for isolation precautions: Preventing transmission of infectious agents in healthcare settings. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/infectioncontrol/guidelines/isolation/index.html ↵

- “contact-precautions-sign-P.pdf” by U.S. Department of Health and Human Services and Centers for Disease Control and Prevention is licensed in the Public Domain. Access for free at https://www.cdc.gov/infectioncontrol/basics/transmission-based-precautions.html#anchor_1564058318 ↵

Precautions used by health care workers during client care when contact or potential contact with blood or body fluids may occur based on the principle that all blood, body fluids (except sweat), nonintact skin, and mucous membranes may contain transmissible infectious agents.

The process of removing, killing, or destroying microorganisms or visible contaminants from the hands.

The removal of microorganisms. However, disinfection does not destroy all spores and viruses.

A process used on equipment and the environment that destroys all pathogens, including spores and viruses.

Absence of all microorganisms during any type of invasive procedure, such as during surgery or heart catheterizations.

Refers to techniques used to prevent the transfer of microorganisms from one person or object to another but do not eliminate all microorganisms.

Involves washing the genital and rectal areas of the body.

Specific types of personal protective equipment (PPE) and practices based on the pathogen’s mode of transmission.