4.3 Defenses Against Transmission of Infection

The body tries to protect itself from infectious agents by using specific and nonspecific defenses. Specific defenses are immune system processes that include white blood cells attacking particular pathogens. Nonspecific defenses are generic barriers that prevent pathogens from entering the body, including physical, mechanical, or chemical barriers.

Physical Defenses

Physical defenses are the body’s most basic form of defenses against infection. Physical defenses include barriers such as skin and mucous membranes, as well as mechanical defenses, that physically remove microbes from areas of the body.[1]

Skin

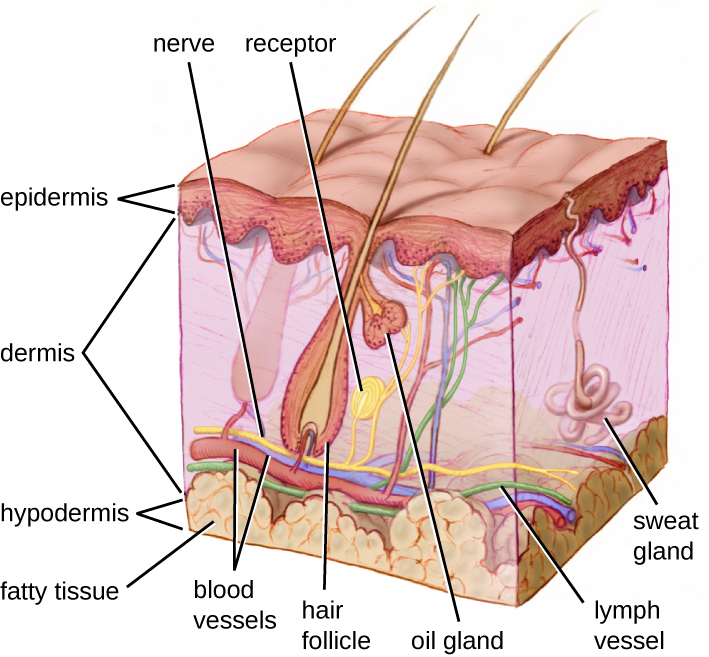

One of the body’s most important physical barriers is the skin barrier that is composed of three layers of closely packed cells. See Figure 4.2[2] for an illustration of layers of the skin. The topmost layer of skin, called the epidermis, consists of cells that are packed with keratin. Keratin makes the skin’s surface mechanically tough and resists degradation by bacteria. When the skin barrier becomes broken, such as becoming cracked from dryness, microorganisms can enter and cause infection.[3]

Mucous Membranes

Mucous membranes lining the nose, mouth, lungs, and urinary and digestive tracts provide another nonspecific barrier against pathogens. Mucous is a moist, sticky substance that covers and protects the layers beneath it and also traps debris, including microbes. Mucus secretions also contain antimicrobial agents.[4]

In many regions of the body, mechanical actions flush mucus (along with trapped microbes) out of the body or away from potential sites of infection. For example, in the respiratory system, inhalation can bring microbes, dust, mold spores, and other small airborne debris into the body. This debris becomes trapped in the mucus lining the respiratory tract. The cells lining the upper parts of the respiratory tract have hair-like appendages known as cilia. Movement of the cilia propels debris-laden mucus out and away from the lungs. The expelled mucus is then swallowed (and destroyed in the stomach) or coughed out. However, smoking limits the efficiency of this system, making smokers more susceptible to developing respiratory infections. Additionally, as people age, their chest muscles weaken, and coughing becomes less productive, which also increases the risk of developing a respiratory infection.

Mechanical Defenses

In addition to physical barriers, the body has several mechanical defenses that physically remove pathogens from the body and prevent infection. For example, the flushing action of urine carries microbes away from the body and is responsible for maintaining a sterile environment of the urinary tract.

The eyes have additional physical barriers and mechanical mechanisms for preventing infections. Eyelashes and eyelids are physical barriers that prevent dust and airborne microorganisms from reaching the surface of the eye. Any microbes or debris that make it past these physical barriers are flushed out by the mechanical action of blinking. Blinking bathes the eye in tears and washes debris away.[5] See Figure 4.3[6] for an example of eyelashes as a mechanical defense.

Chemical Defenses

In addition to physical and mechanical defenses, our immune system uses several chemical defenses that inhibit microbial invaders. The term chemical mediators refers to a wide array of substances found in various fluids and tissues throughout the body. For example, sebaceous glands in the dermis secrete an oil called sebum that is released onto the skin surface through hair follicles. Sebum provides an additional layer of defense by helping seal off the pore of the hair follicle and preventing bacteria on the skin’s surface from invading sweat glands and surrounding tissue. However, environmental factors can affect these chemical defenses of the skin. For example, low humidity in the winter dries the skin and makes it more susceptible to pathogens that are normally inhibited by the skin’s low pH. Application of skin moisturizer restores moisture and essential oils to the skin and helps prevent dry skin from becoming infected.[7]

Other types of chemical defenses are pH levels, chemical mediators, and enzymes. For example, in the urinary tract, the slight acidity of urine inhibits the growth of potential pathogens in the urinary tract. The respiratory tract has various chemical mediators in the nasal passages, trachea, and lungs that have antibacterial properties. Enzymes in the digestive tract eliminate most microorganisms that survive the acidic environment of the stomach. However, feces, the end product of the digestive system, can still contain some microorganisms. For this reason, hand hygiene is vital after using the restroom or assisting a client with perineal care to prevent the spread of infection.[8]

- This work is a derivative of Microbiology by OpenStax and is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/microbiology/pages/1-introduction ↵

- “OSC_Microbio_17_02_Skin.jpg” by OpenStax is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/microbiology/pages/17-1-physical-defenses ↵

- This work is a derivative of Microbiology by OpenStax and is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/microbiology/pages/1-introduction ↵

- This work is a derivative of Microbiology by OpenStax and is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/microbiology/pages/1-introduction ↵

- This work is a derivative of Microbiology by OpenStax and is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/microbiology/pages/1-introduction ↵

- “Eyelashes_of_a_2-month-old_baby_boy.png” by Karthik.yerramilly is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0 ↵

- This work is a derivative of Microbiology by OpenStax and is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/microbiology/pages/1-introduction ↵

- This work is a derivative of Nursing Fundamentals by Chippewa Valley Technical College and is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

Immune system processes like white blood cells attacking particular pathogens.

Generic barriers that prevent pathogens from entering the body, including physical, mechanical, or chemical barriers.