8.4 Applying the Nursing Process to Bipolar Disorders

Assessment (Recognize Cues)

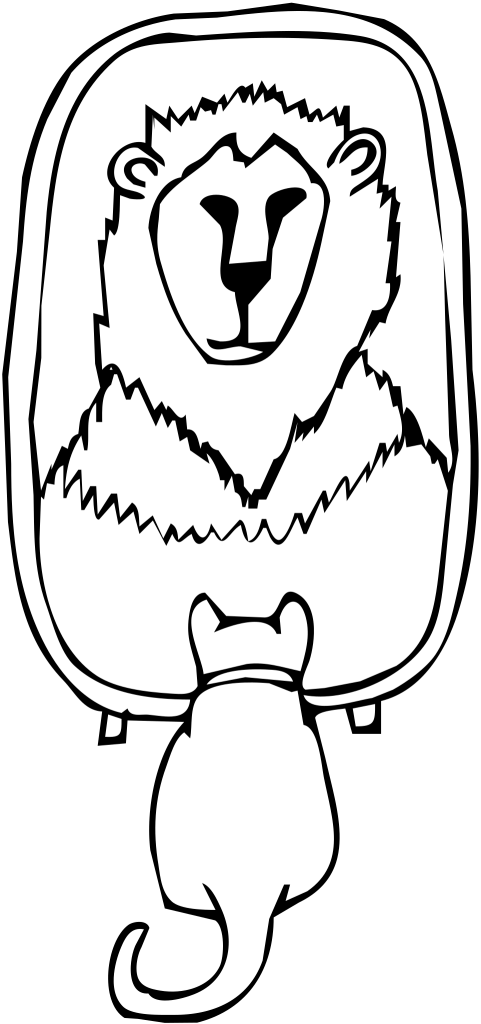

Assessment of a client with a mood disorder focuses on both verbal and nonverbal cues. People with bipolar disorder experience periods of unusually intense emotion, grandiose delusions, changes in sleep patterns and activity levels, and impulsive behaviors, often without recognizing potential harmful effects.[1] See Figure 8.3[2] for an artistic depiction of grandiose delusions when a cat looking in a mirror sees a lion.

It is often helpful to interview family members or significant others of clients with mood disorders. Clients with mania, hypomania, or psychosis often have poor insight and may have difficulty providing an accurate history.[3]

Safety guidelines for assessing a client with a bipolar disorder include the following:[4]

- Assess if the client is a danger to self or others. The client may have suicidal or homicidal ideation. Poor impulse control may result in harm to self or others. Assess the need for protection from uninhibited behaviors. For example, external controls may be needed to protect the client from consequences such as bankruptcy.

- Assess physiological stability while obtaining vital signs and lab results, including electrolytes. The client may not eat or sleep for days at a time with potential physiological consequences.

Mental Status Examination

Table 8.4a outlines typical assessment findings a nurse may observe in a client experiencing a manic episode. Typical findings relate to mood, behavior, thought processes, speech patterns, and cognitive function.

Table 8.4a. Typical Mental Status Examination Findings for a Client Experiencing a Manic Episode[5],[6],[7]

| Assessment | Typical Findings During a Manic Episode |

|---|---|

| Level of Consciousness and Orientation |

|

| Mood and Affect |

|

| Appearance and General Behavior |

|

| Speech |

|

| Motor Activity |

|

| Thought and Perception |

|

| Attitude and Insight |

|

| Cognitive Abilities |

|

Psychosocial Assessment

It is helpful to begin the psychosocial assessment by obtaining the reason why the client is seeking health care in their own words. For example, the client may identify a problem such as a relationship issue, stressful job, or school challenges that could be addressed by counseling.[8]

A comprehensive psychosocial assessment includes the following components:

- Reason for seeking health care (i.e., “chief complaint”)

- Thoughts of suicide or self-injury

- Cultural assessment

- Spiritual assessment

- Family dynamics

- Current and past medical history

- Current medications

- History of previously diagnosed mental health disorders

- Previous hospitalizations

- Educational background

- Occupational background

- History of exposure to psychological trauma, violence, and domestic abuse

- Substance use (tobacco, alcohol, recreational drugs, misused prescription drugs)

- Family history of mental illness

- Coping mechanisms

- Functional ability/Activities of daily living

After identifying the reason the client is seeking health care, additional focused questions are used to obtain detailed information. The mnemonic PQRSTU can be used to ask questions in an organized fashion. See Table 8.4b for a sample PQRSTU assessment for assessing mania.

Table 8.4b. Sample PQRSTU Questions for Assessing Mania[9]

| PQRSTU | Sample Questions | Sample Client Response |

|---|---|---|

| Provocation/Palliation

|

“What tends to trigger or worsen your high energy or mood? What helps calm you down?” | “Stress or excitement can set me off. When I start a new project, I can’t stop. Sleeping helps a bit, but I don’t need much of it.” |

| Quality | “How would you describe what you’re feeling when you’re in a high or elevated mood?” | “It feels amazing—like I’m unstoppable and full of ideas. My mind races, and I have so much energy.” |

| Region | “Do you experience physical symptoms or sensations when you’re in a manic state?” | “My body feels like it’s buzzing—I can’t sit still. I talk fast, move a lot, and sometimes forget to eat.” |

| Severity | “On a scale of 0 to 10, how intense do your manic symptoms feel when they’re at their worst?” | “When they’re really intense, it’s a 10. I feel like I can change the world! But after that I usually crash really hard.” |

| Timing/Treatment | “When did this elevated mood or energy begin? How long does it usually last?” | “It started about a week ago. I don’t feel tired and I’ve barely slept. When these feelings start, I often go days like this.” |

| Understanding | “What do you think is happening when you feel this way? Do you think you need help for these feelings” | “I just feel super productive and creative. I don’t think I need help. Everyone else is just too slow.” (Note: Insight is often impaired during manic episodes, affecting treatment adherence. This question helps assess insight level and readiness for engagement in care.) |

Suicide and Self-Injury Screening

Clients being evaluated or treated for bipolar disorder may have suicidal ideation. The Patient Safety Screener (PSS-3) is an example of a brief screening tool to detect suicide risk in all client presenting to acute care settings.[10]

Non-suicidal self-injury (NSSI) refers to intentional self-inflicted destruction of body tissue without suicidal intention and for purposes not socially sanctioned. Common forms of NSSI include behaviors such as cutting, burning, scratching, and self-hitting. It is considered a maladaptive coping strategy without the desire to die. NSSI is a common finding among adolescents and young adults in psychiatric inpatient settings.[11]

Review information about suicide screening, the Patient Safety Screener, and screening for non-suicidal self-injury (NSSI) in the “Assessment” section of the Applying the Nursing Process to Mental Health Care” chapter.

Cultural Assessment

Cultural formulation interview (CFI) questions help nurses understand a client’s cultural background and how it influences their experience of mental health symptoms, including manic and depressive episodes.[12] Sample CFI questions focused specifically on understanding mania and bipolar disorders within a cultural context include the following:

- Cultural Definition of the Problem

- “How would you describe the changes in your mood or energy that you’ve been experiencing?”

- “In your community or family, what do people call this kind of problem—feeling very ‘up’ or energetic at times, and very ‘down’ at others?”

- Do you feel this is as a medical issue, a spiritual issue, or something else?”

- Cultural Perceptions of Cause, Context, and Support

- “What do you think has caused these shifts in your mood or energy?”

- “Have there been any stressors, life events, or spiritual changes that you believe might explain this?”

- “Do other people in your family or community view these mood changes as a strength, a weakness, or something else?”

- Cultural Factors Affecting Coping and Help-Seeking

- “When you feel very energetic or very low, how do you usually cope with those feelings?”

- “Have you sought help from anyone—such as a spiritual leader, traditional healer, or family member?”

- “Are there treatments or practices you trust or prefer when managing your health?”

- Cultural Features of the Nurse–Client Relationship

- “Are there any concerns you have about talking to a mental health professional?”

- “Would you feel more comfortable speaking with someone of a similar gender, cultural, or religious background?”

- “What would help you feel more supported or understood during treatment?”

Findings from the cultural formulation interview are used to individualize a client’s plan of care to their preferences, values, beliefs, and goals.

Spiritual Assessment

The FICA© spiritual history tool is a widely used assessment model for evaluating a client’s spiritual beliefs and how they may influence health, illness, and coping. It’s especially helpful in understanding how clients with bipolar disorder draw on spirituality or religion for support. Addressing a client’s spirituality and advocating spiritual care have been shown to improve clients’ health and quality of life.[13],[14]

The FICA© spiritual history tool is a common tool used to gather information about a client’s spiritual history and preferences. FICA© is a mnemonic for the domains of Faith, Importance, Community, and Address in Care.[15] Table 8.4c summarizes a sample FICA spiritual assessment and sample responses from a client experiencing bipolar disorder.

Table 8.4c. Sample FICA Spiritual Assessment Questions for Clients With Bipolar Disorder

| Domain | Sample Assessment Question | Sample Client Response |

|---|---|---|

| Faith | “Do you consider yourself spiritual or religious? What gives your life meaning?” | “During my high periods, I sometimes feel like I’m on a mission from God. When I crash, I feel abandoned or punished.” |

| Importance | “What importance does your faith or belief have in your life? Has it influenced how you cope with your mood changes?” | “My faith can be confusing at times depending on how I’m feeling. When I’m up, it can feel like a blessing because I am so productive and can get so much done. When I’m down, I question everything and wonder why I am being punished with these up and down periods.” |

| Community | “Are you part of a spiritual or religious community? Do they provide support to help manage your health or emotions?” | “When I’m feeling depressed, I don’t feel like going to church. I haven’t talked to anyone about what happens during my up periods.” |

| Address in Care | “How would you like me (or the health care team) to address spiritual issues during your care? Would you like to speak with a chaplain or contact your pastor?” | “Yes, I would be interested in speaking to a chaplain.” |

Nurses may recognize cues of spiritual distress related to feelings or behaviors that occur during manic and depressive episodes. Nurses can offer to connect the client with a chaplain or spiritual care services. Spiritual goals may be included in the nursing care plan if the client finds them valuable.

Family Dynamics

Family dynamics are included in a psychosocial assessment, especially for children, adolescents, and older adults. Family dynamics refers to the patterns of interactions among relatives, their roles and relationships, and the various factors that shape their interactions. Because family members rely on each other for emotional, physical, and economic support, they are primary sources of relationship security or stress. Family dynamics and the quality of family relationships can have either a positive or negative impact on an individual’s mental health. For example, secure and supportive family relationships can provide love, advice, and care, whereas stressful family relationships can be burdened with arguments, unhealthy relationships, and a lack of support.[16]

Screening Tools

Many screening tools exist to assess mood disorders. Common examples include the following:

Mood Disorder Questionnaire (MDQ) PDF: Thirteen questions with yes/no responses for assessing mania.

Young Mania Rating Scale (YMRS) PDF: An 11-item assessment based on the client’s subjective report of behaviors over the past 24 hours regarding manic symptoms. It is useful to evaluate baseline functioning and progress being made. There is also a parent version for assessing children and adolescents.

Altman Self-Rating Mania Scale: A self-assessment questionnaire to evaluate the severity of mania or hypomania.

Laboratory Testing

Initial medical evaluation of clients with a possible or established diagnosis of bipolar disorder typically includes the following:

- Thyroid stimulating hormone

- Complete blood count

- Chemistry panel

- Urine toxicology to screen for substances of abuse

Thereafter, routine laboratory testing for clients with bipolar disorders can include these items:

- Therapeutic Medication Levels: Medication dosages may need adjustment based on blood levels to avoid toxicity and ensure they are in therapeutic range. Read more about therapeutic drug levels under the “Medications” subsection of the “Treatments for Bipolar Disorders” section of this chapter.

- Kidney or liver function tests, based on medications prescribed.

- Thyroid function studies and calcium levels.

- Nutrition or hydration status, such as serum sodium levels, hematocrit, albumin, and prealbumin levels, which can become impaired during manic episodes due to poor intake.

Reflective Questions

- What are some common underlying medical conditions that could potentially mimic the symptoms of mania in older adults?

- Why are some individuals with bipolar disorder misdiagnosed with schizophrenia?

Life Span Considerations

Life span considerations influence how the client is assessed, as well as the selection of appropriate nursing interventions.

Children and Adolescents

Most cases of bipolar disorder are diagnosed in adolescence or adulthood, but the symptoms can appear earlier in childhood. While less common than in adults, it is possible for children to experience manic and depressive episodes, especially if there is a family history of bipolar disorder. Research also indicates that trauma and adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) may increase the chances of developing bipolar disorder in people with a genetic risk of having the condition. The symptoms of manic episodes may look different in children than in adults, often presenting as significant irritability mood swings, changes in sleep patterns, and destructive outbursts. Depressive episodes may present as somatic complaints or withdrawal. Bipolar disorder may be misdiagnosed as ADHD, ODD, or conduct disorder.[17] Review information about adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) in the “Mental Health and Mental Illness” section of Chapter 1.

Older Adults

Onset of bipolar disorder after age 60 is rare. Individuals often present with depression as the primary symptom rather than hypomania or mania. New symptoms of mania and should be communicated to the health care provider for investigation of medical causes such as stroke, thyroid dysfunction, or dementia.[18]

Diagnosis (Analyze Cues)

Mental health disorders are diagnosed by trained mental health professionals using the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5-TR). Nurses create individualized nursing care plans using nursing diagnoses based on the client’s response to their mental health disorders. Examples of common nursing diagnoses associated with bipolar disorders are listed in Table 8.4d.

Table 8.4d. Common Nursing Diagnoses Related to Bipolar Disorder[19],[20]

| Nursing Diagnosis | Associated Behaviors and Characteristics |

|---|---|

| Safety: Risk for Injury Risk for Suicide Risk for Violence |

Impulsive, risky behaviors with poor personal boundaries. Lack of insight into illness. May exhibit agitation, self-harm, or threatening behaviors. |

| Communication: Impaired Cognition Impaired Communication |

Grandiose thinking with poor judgment, flight of ideas, or pressured speech with loose associations. |

| Self-Care Deficit: Bathing, Grooming, Hygiene, Dressing | Poor hygiene and distracted from tasks. |

| Impaired Nutrition | Unable to sit long enough to eat; poor appetite. May eat excessive amounts of food during hypomanic episodes. |

| Disturbed Sleep Patterns | Inability to rest or sleep without frequent awakenings; often hyperactive at night. |

| Fatigue r/t Psychological Demands | Hyperactive and restless. |

| Social Isolation r/t Ineffective Coping or Intrusive Behaviors | Feel different from others and preoccupied with own thoughts. Social behavior may be incongruent with norms. May demonstrate an excessive amount of verbal exchange or violation of personal boundaries. May engage in inappropriate sexual language or behavior. |

| Risk for Spiritual Distress | Demonstrate ineffective coping strategies, separation from support system, or hopelessness. |

Outcome Identification (Generate Solutions)

During an acute manic episode, the overall goals are symptom management, achieving remission of symptoms, preventing injury, and supporting physiological integrity. Examples of goals during the acute phase include the following[21]:

- Maintain stable cardiac status.

- Be well-hydrated.

- Get sufficient sleep and rest.

- Make no attempt at self-harm.

- Demonstrate thought control with the aid of staff and/or medication.

- Maintain tissue integrity.

The maintenance phase occurs after acute symptoms have been controlled and the goals become focused on preventing future exacerbations of manic episodes through education, support, and problem-solving skills. The following are examples of goals during the maintenance phase[22]:

- Identifying and avoiding triggers for developing acute mania

- Attending therapy sessions

- Developing new coping skills

Outcome criteria are identified based on the phase of bipolar illness the client is experiencing, either acute or maintenance phase.[23] SMART outcomes are Specific, Measurable, Attainable/Actionable, Relevant, and Timely. Read more about SMART outcomes in the “Application of the Nursing Process in Mental Health Care” chapter. The following are sample SMART outcomes for clients with bipolar disorders:

- The client will communicate feelings and thoughts of self-harm (self-injury) to the health care team, prior to acting on thoughts, during this shift.

- The client will eat breakfast within one hour of the arrival of the breakfast tray.

- The client will attend one or more group meetings each day while in the outpatient setting.

Planning (Generate Solutions)

Safety

Clients with bipolar disorders are monitored closely for risk of suicide, and interventions are planned according to their level of risk. Review interventions for clients at risk of suicide in the “Application of the Nursing Process in Mental Health Care” chapter.

Planning Interventions During Acute Manic Episodes

When a client is hospitalized during an acute manic episode, planning focuses on stabilizing the client while maintaining safety. Nursing care focuses on managing medications, decreasing physical activity, increasing food and fluid intake, reinforcing a minimum of four to six hours of sleep per night, and ensuring self-care needs are met.[24]

Planning Interventions During the Maintenance Phase

During the maintenance phase, planning focuses on preventing relapse and limiting the severity and duration of future episodes. During this period, individuals with bipolar disorders often face multiple hardships resulting from their behaviors during previous acute manic episodes. Interpersonal, occupational, educational, and financial consequences may occur. Clients need support as they recover from acute illness and repair their lives.[25]

Individuals are often ambivalent about treatment, but bipolar disorders typically require medications to be taken over long periods of time or for a lifetime to prevent relapse. Self-medication through alcohol or other substances often complicates recovery and treatment. Nurses must establish a therapeutic nurse-client relationship to support continued treatment. See Chapter 2 for additional information on establishing a therapeutic nurse-client relationship. Individuals are typically referred to community resources and outpatient mental health care settings. In addition to medication management, outpatient services provide structure and decrease social isolation.[26]

Implementation (Take Action)

Nursing Interventions for Clients With Bipolar Disorder Based on Categories of the APNA Implementation Standard

Nursing interventions for clients with bipolar disorders can be categorized based on the American Psychiatric Nurses Association (APNA) standard for Implementation that includes the Coordination of Care; Health Teaching and Health Promotion; Pharmacological, Biological, and Integrative Therapies; Milieu Therapy; and Therapeutic Relationship and Counseling. Read more about these subcategories in the “Application of the Nursing Process in Mental Health Care” chapter. See examples of interventions for each of these categories for clients with bipolar disorders in Table 8.4e.

Table 8.4e. Nursing Interventions for Mania Based on the Categories of the APNA Implementation Standard[27]

| Categories of Interventions Based on the APNA Standard of Implementation | What the nurse will do… | Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| Coordination of care |

|

|

| Health Teaching and Health Promotion |

|

|

| Pharmacological, Biological, and Integrative Therapies |

|

|

| Milieu Therapy |

|

|

| Therapeutic Relationship and Counseling |

|

|

Nursing Interventions for Physiological Symptoms of Manic and Depressive Episodes

Nurses implement interventions for common physiological symptoms that occur during manic and depressive episodes. Table 8.4f summarizes these interventions.

Table 8.4f. Nursing Interventions to Promote Physiological Integrity During Manic Episodes[28]

| Problem/ Intervention | Rationale |

|---|---|

Nutrition

|

During manic phases, clients may experience hyperactivity and decreased appetite, whereas during depressive phases, they may have overeating or loss of appetite. Medication can also cause weight gain or metabolic syndrome, requiring dietary management. Ensure adequate dietary and fluid intake and minimize development of dehydration. “Finger foods” allow for “eating on the run.” |

Sleep/Rest

|

Manic episodes often cause reduced need for sleep or insomnia, which can worsen symptoms. Depressive episodes may cause excessive sleep or poor sleep quality, impacting recovery and energy. Sleep regulation supports mood stabilization. Bedtime routines and relaxation techniques induce sleep. Encouraging bedtime routines and decreasing caffeine intake increase the possibility of sleep.[29]

|

Elimination (Constipation)

|

Psychotropic medications commonly cause constipation or urinary retention, which may be exacerbated by poor diet or decreased mobility during depressive episodes. Regular monitoring ensures comfort and safety. Fluids and fiber stimulate peristalsis and soft stools. The client experiencing acute mania is easily distracted and not aware of bodily needs. Bowel management programs may be needed to avoid fecal impaction. |

Self-Care Deficits

|

Both manic and depressive episodes can lead to neglect of hygiene and daily routines due to distractibility, low energy, or impaired insight. Supporting ADLs helps maintain dignity, identity, and structure. Distractibility and poor concentration are countered through simple, concrete instructions. |

Communication Tips for Clients With Bipolar Disorder

Clients experiencing mania may be easily agitated or hyperverbal. Communication tips are summarized in the following box.

Effective Communication Tips for Clients With Manic Episode of Bipolar Disorder

- Maintain a calm, non-reactive demeanor.

- Rationale: A calm and steady tone helps de-escalate emotional intensity and provides a model of self-regulation.

- Use short, clear, and concrete statements.

- Rationale: During mania, attention span and focus are impaired. Direct, simple communication prevents confusion and helps the client process instructions more effective.

- Avoid arguing or challenging grandiose ideas.

- Rationale: Debating delusional or inflated beliefs can increase defensiveness and agitation. Instead, acknowledge the emotion behind the belief and gently redirect without confrontation.

- Set firm but respectful personal boundaries and limits on behaviors.

- Rationale: Clients may become intrusive, impulsive, or overstimulated. Clear, consistent boundaries help ensure safety for the client and others.

- Validate emotions. For example, say, “It sounds like you’re feeling really energized today” instead of reinforcing behaviors by saying, “Wow, you’ve done so much!”

- Rationale: Validating emotions promotes insight into behaviors.

- Reinforce reality gently and consistently.

- Rationale: During manic episodes, reality orientation may be impaired. Use clear reminders such as, “Today is Monday, and the group therapy session is this afternoon” to ground the conversation.

- Monitor for rapid topic changes and redirect.

- Rationale: Clients experiencing mania often exhibit flight of ideas. Respectfully bring the focus back to the established topic to gather accurate information. For example, “Earlier you mentioned you were having problems sleeping – let’s talk more about that.”

- Acknowledge progress and small successes.

- Rationale: Positive reinforcement builds self-esteem. Celebrate even small steps toward recovery.

- Assess safety and ask directly about suicidal or homicidal risk, such as, “Have you had any thoughts of hurting yourself or others?”

- Rationale: Direct questioning ensures timely intervention to reduce risk of harm. If a client demonstrates agitation with escalation of manic behavior, review interventions described in the “Crisis and Crisis Intervention” section of the “Stress, Coping, and Crisis Intervention” chapter. Additional de-escalation techniques to maintain safety are described in the “Workplace Violence” section of the “Trauma, Abuse, and Violence” chapter.

Client Education for Bipolar Disorder

Living with bipolar disorder can be challenging, but there are ways to control symptoms and live a healthy life. The client may be resistant to teaching during the acute phase of a manic episode, so it is beneficial to wait until manic symptoms begin to resolve. Client education topics are described in the following box.

Client Education: Bipolar Disorder

Client education regarding bipolar disorder includes the following guidelines[30]:

-

- Get treatment and stay committed to it. Recovery from a manic episode takes time and it’s not easy, but treatment is the best way to start feeling better.

- Keep medical and therapy appointments and talk with the provider about treatment options.

- Take all medicines as directed.

- Maintain a structure for daily activities; keep a routine for eating, getting enough sleep, and exercising.

- Learn to recognize mood swings and warning signs for manic episodes such as decreased need for sleep.

- Ask for help when experiencing barriers or challenges for treatment. Social support helps coping.

- Be patient; improvement takes time.

- Avoid using alcohol and illicit drugs.

- Encourage participation in cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) or dialectical behavioral therapy (DBT).

- Use stress management, relaxation techniques, and coping strategies to minimize anxiety.

- Participate in support groups.

Read more information about the following support groups using the following information:

National Alliance on Mental Illness (NAMI)

Depression and Bipolar Support Alliance (DBSA)

Implementing Seclusion or Restraints

De-escalation techniques should be attempted at early signs of escalating agitation to avoid the need for seclusion or restraints. However, if a client is escalating out of control to a point where they pose an immediate risk of injury to themselves or others, the use of medications, seclusion, or restraints may become necessary to maintain a safe environment. Most state laws prevent the use of unnecessary restraint or seclusion, so their use is associated with complex ethical, legal, and therapeutic issues.[31] Review ANA guidelines on using restraints in the “Client Rights” section of the “Legal and Ethical Considerations in Mental Health Care” chapter and information on safely implementing restraints in the “Workplace Violence” section of the “Trauma, Abuse, and Violence” chapter.

Controlling escalating agitation during the acute phase of a manic episode may include immediate administration of a prescribed antipsychotic and/or benzodiazepine. A combination of haloperidol (Haldol) and lorazepam (Ativan) that can be injected for rapid onset of action is commonly used. The nurse must monitor for respiratory depression, hypotension, and oversedation after administering these types of medication.

Evaluation (Evaluate Outcomes)

Evaluation occurs continuously throughout the treatment of bipolar disorders. The registered nurse individualizes assessments based on the established goals and SMART outcomes for each client. The effectiveness of nursing and collaborative interventions is evaluated and revised as needed. Questions used to guide the evaluation process include the following:

- Is the client medically stable with nutritional intake, sleep patterns, labs, or activity levels?

- Is the client engaging in self-care measures?

- Is the client safe with no self-harm behaviors, statements, gestures, or threats of harm towards others?

- Is the client engaging appropriately in unit-based activities and the therapeutic milieu?

- Is the client able to maintain appropriate personal boundaries with others?

- Is the client able to engage appropriately in verbal conversations and interactions with others?

- Is the client able to demonstrate insight into own illness?

- Is the client tolerating prescriptive medications at therapeutic serum levels and without key side effects?

- Is the client at or near baseline optimal functioning without manic symptoms?

- Is the client able to participate in their own plan of care, including discharge planning?

- National Institute of Mental Health. (2024). Bipolar disorder. National Institutes of Health. https://www.nimh.nih.gov/health/topics/bipolar-disorder ↵

- “Cat_and_lion_in_mirror_illustration.svg” by Arlo Barnes is licensed under CC BY 3.0 ↵

- Suppes, T. (2021). Bipolar disorder in adults: Assessment and diagnosis. UpToDate. https://www.uptodate.com/ ↵

- Halter, M. (2022). Varcarolis’ foundations of psychiatric-mental health nursing (9th ed.). Saunders. ↵

- National Institute of Mental Health. (2024). Bipolar disorder. National Institutes of Health. https://www.nimh.nih.gov/health/topics/bipolar-disorder ↵

- Halter, M. (2022). Varcarolis’ foundations of psychiatric-mental health nursing (9th ed.). Saunders. ↵

- Suppes, T. (2021). Bipolar disorder in adults: Assessment and diagnosis. UpToDate. https://www.uptodate.com/ ↵

- Halter, M. (2022). Varcarolis’ foundations of psychiatric-mental health nursing (9th ed.). Saunders. ↵

- National Institute of Mental Health. (2024). Bipolar disorder. National Institutes of Health. https://www.nimh.nih.gov/health/topics/bipolar-disorder ↵

- Suicide Prevention Resource Center. (n.d.). The patient safety screener: A brief tool to detect suicide risk. https://sprc.org/micro-learning/patientsafetyscreener ↵

- Cipriano, A., Cella, S., & Cotrufo, P. (2017). Nonsuicidal self-injury: A systematic review. Frontiers in Psychology, 8. https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpsyg.2017.01946/full ↵

- DeSilva, R., Aggarwall, N. K., & Lewis-Fernandez, R. (2015). The DSM-5 cultural formulation interview and the evolution of cultural assessment in psychiatry. Psychiatric Times, 32(6). https://www.psychiatrictimes.com/view/dsm-5-cultural-formulation-interview-and-evolution-cultural-assessment-psychiatry ↵

- Pilger, C., Molzahn, A. E., de Oliveira, M. P., & Kusumota, L. (2016). The relationship of the spiritual and religious dimensions with quality of life and health of patients with chronic kidney disease: An integrative literature review. Nephrology Nursing Journal: Journal of the American Nephrology Nurses’ Association, 43(5), 411–426. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30550069/ ↵

- Puchalski, C., Jafari, N., Buller, H., Haythorn, T., Jacobs, C., & Ferrell, B. (2020). Interprofessional spiritual care education curriculum: A milestone toward the provision of spiritual care. Journal of Palliative Medicine, 23(6), 777–784. https://doi.org/10.1089/jpm.2019.0375 ↵

- GW School of Medicine & Health Sciences. (n.d.). Clinical FICA tool. https://smhs.gwu.edu/spirituality-health/program/transforming-practice-health-settings/clinical-fica-tool ↵

- Jabbari, B., Schoo, C., & Rouster, A. S. (2023). Family dynamics. StatPearls [Internet]. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK560487/ ↵

- Cleveland Clinic. (2022). Bipolar disorder in children. https://my.clevelandclinic.org/health/diseases/14669-bipolar-disorder-in-children ↵

- Tampi, R. (2023). Assessment and management of bipolar disorder in older adults. Psychiatric Times, 40(12). https://www.psychiatrictimes.com/view/assessment-and-management-of-bipolar-disorder-in-older-adults ↵

- Ackley, B., Ladwig, G., Makic, M. B., Martinez-Kratz, M., & Zanotti, M. (2020). Nursing diagnosis handbook: An evidence-based guide to planning care (12th ed.). Elsevier. ↵

- Halter, M. (2022). Varcarolis’ foundations of psychiatric-mental health nursing (9th ed.). Saunders. ↵

- Halter, M. (2022). Varcarolis’ foundations of psychiatric-mental health nursing (9th ed.). Saunders. ↵

- Halter, M. (2022). Varcarolis’ foundations of psychiatric-mental health nursing (9th ed.). Saunders. ↵

- Halter, M. (2022). Varcarolis’ foundations of psychiatric-mental health nursing (9th ed.). Saunders. ↵

- Halter, M. (2022). Varcarolis’ foundations of psychiatric-mental health nursing (9th ed.). Saunders. ↵

- Halter, M. (2022). Varcarolis’ foundations of psychiatric-mental health nursing (9th ed.). Saunders. ↵

- Halter, M. (2022). Varcarolis’ foundations of psychiatric-mental health nursing (9th ed.). Saunders. ↵

- Halter, M. (2022). Varcarolis’ foundations of psychiatric-mental health nursing (9th ed.). Saunders. ↵

- Halter, M. (2022). Varcarolis’ foundations of psychiatric-mental health nursing (9th ed.). Saunders. ↵

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2024). About sleep. https://www.cdc.gov/sleep/about/index.html#cdc_behavioral_basics_steps-what-to-do ↵

- National Institute of Mental Health. (2020). Bipolar disorder. National Institutes of Health. https://www.nimh.nih.gov/health/topics/bipolar-disorder ↵

- Halter, M. (2022). Varcarolis’ foundations of psychiatric-mental health nursing (9th ed.). Saunders. ↵

Refers to the patterns of interactions among relatives, their roles and relationships, and the various factors that shape their interactions.