15.3 Trauma-Informed Care

Trauma has no age, gender, socioeconomic status, race, ethnicity, or sexual orientation boundaries. Individual trauma results from an event, series of events, or set of circumstances that is experienced by an individual as physically or emotionally harmful or life-threatening and can have lasting adverse effects on their functioning and mental, physical, social, emotional, or spiritual well-being. Adverse childhood experiences are examples of individual traumas.[1]

It is natural to feel afraid during and after a traumatic situation. The “fight, flight or freeze” reaction caused by the physiological stress response is intended to protect a person from harm. The sympathetic nervous system (SNS) automatically and unconsciously triggers this physiological stress response whenever there is a perception of threat.[2]

- Review the physiology of the sympathetic nervous system and the parasympathetic nervous system in the “Psychotropic Medications” chapter.

- Review activation of the stress response in the “Stress, Coping, and Crisis Intervention” chapter.

The SNS activates many organs during the stress response, resulting in symptoms like increased heart rate, increased blood pressure, rapid breathing, and tense muscles. Cumulative adverse childhood experiences can maintain this threat response in people’s brains, which, over time, can “rewire” their level of physiological reactivity to stress and affect emotional regulation like depression, anxiety, and substance abuse. Trauma survivors are also susceptible to chronic physical and mental illnesses and suicide.[3] There also tends to be a decrease in positive social behaviors (such as collaboration and kindness) in individuals experiencing a chronic stress response because it requires their full cognitive capacity to respond by “fighting, fleeing, or freezing.”

Arousal and reactivity symptoms include the following[4]:

- Being easily startled

- Feeling tense or “on edge”

- Having difficulty sleeping

- Having angry outbursts

These symptoms can make the person feel stressed and angry and can make it hard to do daily tasks, such as sleeping, eating, or concentrating.[5]

Individuals who have a history of trauma may become triggered by engagement with the health care system. They may experience arousal and reactivity symptoms. As a result of the stimulation of the “fight, flight, or freeze” stress response, the parts of the brain involved in memory, planning, decision-making, and regulation are not engaged. This can impact the patient’s involvement with health care services and affect their ability to adhere to treatment plans.[6] Nurses must understand this potential impact of previous trauma and incorporate patient-centered, trauma-informed care.

Trauma-informed care is an approach that uses a lens of trauma to understand the range of cognitive, emotional, physical, and behavioral symptoms seen when individuals enter health care systems. Trauma-informed care (TIC) is a strengths-based framework that acknowledges the prevalence and impact of traumatic events in clinical practice, placing an emphasis on instilling in patients a sense of safety, control, and autonomy over their life and health care decisions. The basic goals of TIC are to avoid re-traumatization; emphasize survivor strengths and resilience; aid empowerment, healing, and recovery; and promote the development of survivorship skills.[7]

Two influential studies set the stage for the development of TIC[8]:

- The Adverse Childhood Experiences Study was an extensive study involving more than 17,000 individuals from the United States. It analyzed the long-term effects of childhood and adolescent traumatic experiences on adult health risks, mental health, health care costs, and life expectancy.[9]

- The Women, Co-Occurring Disorders, and Violence Study was a study focused on the role of interpersonal and other traumatic stressors among women. The researchers examined the interrelatedness of trauma, violence, and co-occurring substance use and mental health disorders and the incorporation of trauma-informed services.[10]

The Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) has defined six core principles of TIC. See Figure 15.2[11] for an infographic related to these principles[12]:

- Safety: Throughout the organization, patients and staff feel physically and psychologically safe.

- Trustworthiness and Transparency: Decisions are made with transparency and with the goal of building and maintaining trust.

- Peer Support: Individuals with shared experiences are integrated into the organization and viewed as integral to service delivery.

- Collaboration and Mutuality: Power differences between staff and clients and among organizational staff are leveled to support shared decision-making.

- Empowerment Voice and Choice: Patient and staff strengths are recognized, built on, and validated, including a belief in resilience and the ability to heal from trauma.

- Cultural, Historical, and Gender Issues: Biases and stereotypes (e.g., based on race, ethnicity, sexual orientation, age, geography) and historical trauma are recognized and addressed.

View the following YouTube video on ACEs and trauma-informed care[13]: What is Trauma-Informed Care?

Trauma-Informed Nursing Practice

Nurses can incorporate trauma-informed care by routinely implementing the following practices with all clients[14]:

- Introduce Yourself and Your Role in Every Patient Interaction: Patients may recognize you, but they may not remember your role. This may lead to confusion and misunderstanding. When a patient understands who you are and your role in their care, they feel empowered to be actively engaged in their own care. They also feel less threatened because they know your name and why you are interacting with them. When one party is nameless, there can be an automatic power differential in the interaction.

- Use Open and Nonthreatening Body Positioning: Be aware of your body position when working with patients. Open body language conveys trust and a sense of value. Trauma survivors often feel powerless and trapped. Health care situations can trigger past experiences of lack of control or an inability to escape. Using nonthreatening body positioning helps prevent the threat detection areas of the patient’s brain from taking over and helps patients stay regulated. A trauma-informed approach to body position includes attempting to have your body on the same level as the patient, often sitting at or below the patient. It could also include raising a hospital bed in order for the nurse and the patient to be on the same level, reducing the likelihood of creating a perceived power differential through positioning. Additionally, it is important to think about where you and the patient are positioned in the room in relation to the door or exit. Both nurse and patient should have access to the exit so that neither feels trapped.

- Provide Anticipatory Guidance: Verbalize what the patient can expect during a visit or procedure or what paperwork will cover. Knowing what to expect can reassure patients even if it is something that may cause discomfort. Past trauma is often associated with unexpected and unpredictable events. Knowing what to expect reduces the opportunity for surprises and activation of the SNS symptoms. It also helps patients feel more empowered in the care planning process.

- Ask Before Touching: For many trauma survivors, inappropriate or unpleasant touch was part of a traumatic experience. Touch, even when appropriate and necessary for providing care, can trigger a “fight, flight, or freeze” response and bring up difficult feelings or memories. This may lead to the individual experiencing increased anxiety and activation of the stress response, resulting in disruptive behaviors and possible dissociation. Dissociation is a break in how a person’s mind handles information, causing disconnection from their thoughts, feelings, memories, and surroundings. Nurses are often required to touch patients, and sometimes this touch occurs in sensitive areas. Any touch can be interpreted as unwanted or threatening, so it is important to ask all clients permission to touch them. Asking permission before you touch patients gives them a choice and empowers them to have control over their body and physical space. Be alert to nonverbal signs such as eye tearing, flinching, shrinking away, or other body language indicating the person is feeling uncomfortable. If the client exhibits signs of discomfort when being touched, additional nursing interventions can be implemented such as a mindfulness or grounding practice.

- Protect Patient Privacy: Family members and other members of the medical team may be present when you care for a patient. Patients may not feel empowered or safe in asking others to step out. It is crucial that nurses do not put the responsibility on the patient to ask others to leave. It is the nurse’s role to ask the patient (in private) whom they would like to be present during care and ask others to leave the room.

- Provide Clear and Consistent Messaging About Services and Roles: Trust is built when patients experience care providers who are forthright and honest. Dependability, reliability, and consistency are important when working with trauma survivors because previous trauma was often unexpected or unpredictable. Providing consistency from the nursing team regarding expectations and/or hospital rules can help patients feel secure and decrease opportunities for unmet expectations that might lead to triggering disruptive behavior.

- Use Plain Language and Teach Back: Avoid medical jargon and use clear, simple language. When patients are feeling triggered (i.e., their “fight, flight, or freeze” system is engaged), information processing and learning parts of the brain do not function optimally, and it is hard to remember new information. When providing education, information, or instructions, break information into small chunks and check for understanding. Offer to write important details down so they can accurately recall the information at a later time. Use clear language and “teach back” methods that empower patients with knowledge and understanding about their care.

- Practice Universal Precaution: Universal precaution means providing TIC to all patients regardless of a trauma history. Although ACE screening may be part of routine care, it can also have potential negative effects on patients. Unless a trauma-focused intervention is needed to amend the impact of trauma, many TIC experts propose universal precaution rather than direct screening.

Read a continuing education article titled “Trauma-Informed Nursing Practice” in the American Journal of Nursing.[15]

The Resilient Zone and Self-Regulation Skills

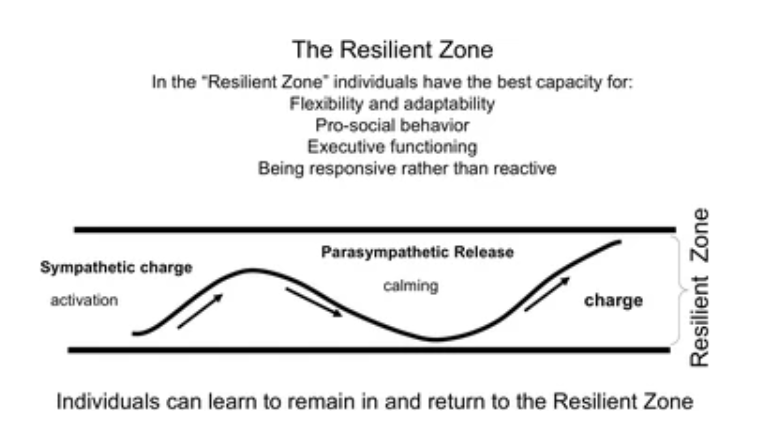

Individuals who have experienced repetitive or cumulative trauma may develop a dysregulated rhythm of their sympathetic nervous system (SNS) and parasympathetic nervous system (PNS), leaving them reactive and stuck in a state of hyperarousal, hypoarousal, or oscillating between the two extremes as their nervous system attempts to find balance. Simply put, the SNS “activates” the stress response, and the PNS “calms” the stress response. When out of balance, individuals may exhibit behaviors such as substance use disorders, self-harming, violence, poor school and work performance, bullying, and social disengagement.[16] Nurses can teach clients self-regulation skills by paying attention to their “fight, flight, or freeze” symptoms and learning how to balance their SNS and PNS systems.

Self-regulation skills teach clients how to return to a healthy balance of SNS and PNS stimulation called the resilient zone. See Figure 15.3[17] for an illustration of the resilient zone when the SNS and PNS are in balance. When in the resilient zone, the hormones released by the SNS during the “fight, flight, or freeze” stress response do not block conscious information processing by the brain. This balance promotes better capacity for flexibility and adaptability, prosocial behavior, improved problem-solving, and strategic thinking.[18]

Teaching self-regulation skills enables the individual to pay attention to symptoms of the stress response and use techniques to purposefully stimulate the PNS. They focus on quality of breath, heart rate, and muscle tension and then use relaxation breathing, progressive muscle relaxation, meditation, or other methods to stimulate the PNS. These skills can be used prior to and during challenging events, as well as practiced over time to build deeper nervous system balance.[19]

Read more about stress management, self-regulation skills, and grounding techniques in the “Stress, Coping, and Crisis Intervention” chapter.

Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) is diagnosed in individuals who have been exposed to a traumatic event with chronic stress symptoms lasting more than one month that are so severe they interfere with relationships, school, or work. PTSD has been placed in a new diagnostic category in the DSM-5 called “Trauma and Stressor-related Disorders.” Read more about PTSD in the “Anxiety Disorders” chapter.

- This work is a derivative of Action steps using ACEs and trauma-informed care: A resilience model by Laurie Leitch and is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- This work is a derivative of Action steps using ACEs and trauma-informed care: A resilience model by Laurie Leitch and is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- Trauma-Informed Care Implementation Resource Center. (n.d.). What is trauma-informed care? Center for Health Care Strategies. https://www.traumainformedcare.chcs.org/what-is-trauma-informed-care/ ↵

- National Institute of Mental Health. (2019, May). Post-traumatic stress disorder. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. https://www.nimh.nih.gov/health/topics/post-traumatic-stress-disorder-ptsd ↵

- National Institute of Mental Health. (2019, May). Post-traumatic stress disorder. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. https://www.nimh.nih.gov/health/topics/post-traumatic-stress-disorder-ptsd ↵

- Fleishman, J., Kamsky, H., & Sundborg, S. (2019, May 31). Trauma-informed nursing practice. OJIN: The Online Journal of Issues in Nursing, 24(2). https://doi.org/10.3912/OJIN.Vol24No02Man03 ↵

- Tracy, E. E., & Macias-Konstantopoulos, W. (2021, August 19). Human trafficking: Identification and evaluation in the health care setting. UpToDate. Retrieved April 4, 2022, from www.uptodate.com ↵

- Center for Substance Abuse Treatment (US). (2014). Trauma-informed care in behavioral health services. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK207201/ ↵

- Felitti, V. J., Anda, R. F., Nordenberg, D., Edwards, V., Koss, M. P., & Marks, J. S. (1998). Relationship of childhood abuse and household dysfunction to many of the leading causes of death in adults: The adverse childhood experience (ACE) study. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 14(3), 245-258. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0749-3797(98)00017-8 ↵

- Clark, H. W., & Power, A. K. (2005). Women, co-occurring disorders, and violence study: A case for trauma-informed care. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 28(2), 145-146. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsat.2005.01.002 ↵

- This image is a derivative of “training_emergency_responders_final.jpg” by Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and in the Public Domain. Access for free at https://www.cdc.gov/cpr/infographics/6_principles_trauma_info.htm ↵

- Trauma-Informed Care Implementation Resource Center. (n.d.). What is trauma-informed care? Center for Health Care Strategies. https://www.traumainformedcare.chcs.org/what-is-trauma-informed-care/ ↵

- Center for Health Care Strategies. (2019, January 23). What is trauma-informed care? [Video]. YouTube. All rights reserved. https://youtu.be/fWken5DsJcw ↵

- Fleishman, J., Kamsky, H., & Sundborg, S. (2019, May 31). Trauma-informed nursing practice. OJIN: The Online Journal of Issues in Nursing, 24(2). https://doi.org/10.3912/OJIN.Vol24No02Man03 ↵

- Dowdell, E., & Speck, P.M. (2022). Trauma-informed care in nursing practice. American Journal of Nursing, 122(4), 30-38. https://journals.lww.com/ajnonline/Fulltext/2022/04000/CE__Trauma_Informed_Care_in_Nursing_Practice.22.aspx ↵

- This work is a derivative of Action steps using ACEs and trauma-informed care: A resilience model by Laurie Leitch and is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- Leitch, L. (2017). Action steps using ACEs and trauma-informed care: A resilience model. Health Justice 5, 5. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40352-017-0050-5 ↵

- This work is a derivative of Action steps using ACEs and trauma-informed care: A resilience model by Laurie Leitch and is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- This work is a derivative of Action steps using ACEs and trauma-informed care: A resilience model by Laurie Leitch and is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

An event, series of events, or set of circumstances that is experienced by an individual as physically or emotionally harmful or life-threatening and can have lasting adverse effects on their functioning and mental, physical, social, emotional, or spiritual well-being.

A strengths-based approach to providing client care that is grounded in an understanding of the impact of trauma. It emphasizes physical, psychological, and emotional safety for both providers and survivors and creates opportunities for survivors to rebuild a sense of control and empowerment referred to as resilience.

A break in how a person’s mind handles information, causing disconnection from their thoughts, feelings, memories, and surroundings.

Healthy balance of SNS and PNS stimulation.