8.2 Basic Concepts of Bipolar Disorders

Manic Episodes

Bipolar disorders include shifts in mood from abnormal highs (called manic episodes) to abnormal lows (i.e., depressive episodes). A manic episode is a persistently elevated or irritable mood with abnormally increased energy lasting at least one week. The mood disturbance is severe and causes marked impairment in social or occupational function. Severe episodes often require hospitalization to prevent harm to self or others. As the manic episode intensifies, the individual may become psychotic with hallucinations, delusions, and disturbed thoughts. The episode is not caused by the physiological effects of a substance (such as drug abuse, prescribed medication, or other treatment) or by another medical condition.[1]

According to the DSM-5-TR, three or more of the following symptoms are present during a manic episode[2]:

- Inflated self-esteem or grandiosity

- Decreased need for sleep (i.e., feels rested after only three hours of sleep)

- More talkative than usual or pressure to keep talking

- Flight of ideas or subjective experience that thoughts are racing

- Distractibility (i.e., attention is too easily drawn to unimportant or irrelevant stimuli)

- Increase in goal-directed activity (either socially, at work or school, or sexually) or psychomotor agitation

- Excessive involvement in activities that have a high potential for painful consequences (e.g., engaging in unrestrained buying sprees, sexual indiscretions, or foolish business investments)

People experiencing a manic episode may become physically exhausted.

Hypomanic Episodes

Hypomanic episodes have similar symptoms to a manic episode but are less severe and do not cause significant impairment in social or occupational functioning or require hospitalization. A hypomanic episode is defined as a distinct period of abnormally and persistently elevated, expansive, or irritable mood, accompanied by increased activity or energy, lasting at least four consecutive days and present most of the day, nearly every day.[3]

During this period, three or more of the following symptoms (or four if the mood is only irritable) must be present to a significant degree, representing a noticeable change from the individual’s typical behavior[4]:

- Inflated self-esteem or grandiosity, decreased need for sleep (e.g., feeling rested after only three hours)

- Being more talkative than usual or feeling pressure to keep talking

- Experiencing flight of ideas or racing thoughts or distractibility

- Increased goal-directed activity or psychomotor agitation

- Excessive involvement in activities with a high potential for painful consequences (such as reckless spending, risky sexual behavior, or unwise business investments)

The episode must be associated with a clear change in functioning that is uncharacteristic of the person when asymptomatic, and this change must be observable by others. However, unlike manic episodes, hypomanic episodes are not severe enough to cause marked impairment in social or occupational functioning or to require hospitalization. If psychotic features are present, the episode is considered manic by definition. The symptoms must not be attributable to the physiological effects of a substance or another medical condition.[5]

Depressive Episodes

A depressive episode is characterized by a persistently low or sad mood and a significant loss of interest or pleasure in most activities. These symptoms must last for at least two weeks and represent a noticeable change from the individual’s typical functioning. Depressive episodes in bipolar disorder are severe and debilitating, often causing marked impairment in social, academic, or occupational performance. Depressive episodes associated with bipolar disorder can lead to suicide. The mortality ratio due to suicide for people with bipolar disorder is 20 times above the general population rate and exceeds rates for other mental health disorders.[6]

Like manic episodes, depressive episodes are not attributable to the physiological effects of a substance or another medical condition.

According to the DSM-5-TR, five (or more) of the following symptoms must be present during the same two-week period, with at least one of the symptoms being either (1) depressed mood or (2) loss of interest or pleasure[7]:

- Depressed mood most of the day, nearly every day (e.g., feels sad, empty, hopeless, or appears tearful)

- Markedly diminished interest or pleasure in all, or almost all, activities

- Significant weight loss when not dieting, weight gain, or a decrease or increase in appetite

- Insomnia or hypersomnia nearly every day

- Psychomotor agitation or retardation observable by others

- Fatigue or loss of energy

- Feelings of worthlessness or excessive or inappropriate guilt

- Diminished ability to think or concentrate or indecisiveness

- Recurrent thoughts of death, suicidal ideation, or suicide attempt

Unlike the increased energy and impulsive behaviors of a manic episode, depressive episodes are characterized by slowed thinking, physical fatigue, and feelings of hopelessness. Individuals may withdraw from others and experience difficulty performing basic daily tasks. In some cases, symptoms become so intense that individuals may experience delusions or hallucinations with depressive content (e.g., believing they are responsible for catastrophic events or hearing voices that reinforce feelings of worthlessness).

Bipolar Disorders

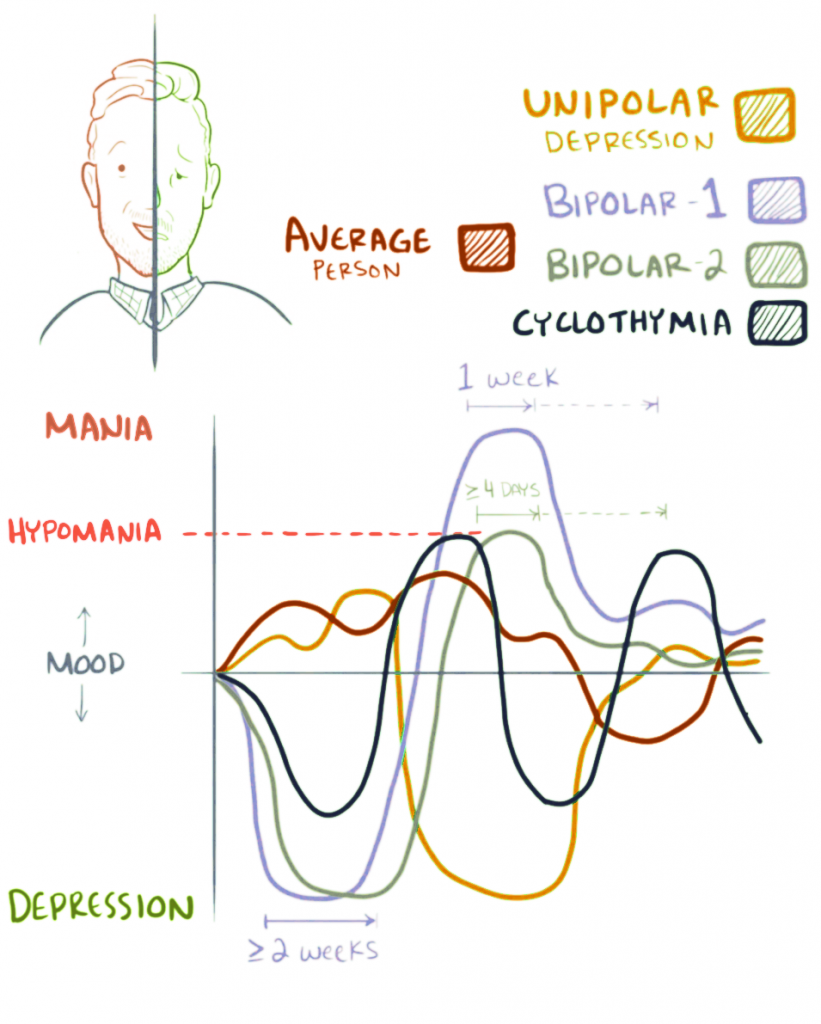

There are three major types of bipolar and related disorders called Bipolar I, Bipolar II, and Cyclothymia. See Figure 8.2[8] for an illustration comparing these three types of bipolar disorders.

Bipolar I disorder is the most severe bipolar disorder. Individuals with Bipolar 1 disorder have had at least one manic episode and often experience additional hypomanic and depressive episodes. (Read about the symptoms of depressive episodes in the “Depressive Disorders” chapter of this book.) One manic episode in the course of an individual’s life can change an individual’s diagnosis from depression to bipolar disorder. Manic episodes last at least one week and are present for most of the day, nearly every day. They can be so severe that the person requires hospitalization. Depressive episodes typically last at least two weeks. Episodes of depression with mixed features (having depressive symptoms and manic symptoms at the same time) are also possible.[9],[10]

Bipolar II disorder is defined by a pattern of depressive episodes and hypomanic episodes. The hypomania episodes last at least four consecutive days and present most of the day, nearly every day, but individuals do not experience the full-blown manic episodes typical of Bipolar I disorder. Individuals with Bipolar II disorder often have higher productivity when they are hypomanic and may exhibit increased irritability.[11], [12]

Cyclothymia is defined by periods of hypomanic symptoms and depressive symptoms lasting for at least two years (1 year in children and adolescents). However, the symptoms do not meet the diagnostic requirements for hypomanic episodes or depressive episodes.[13],[14]

Some people with Bipolar I or Bipolar II disorders experience rapid cycling with at least four mood episodes in a 12-month period. These mood episodes can be manic episodes, hypomanic episodes, or major depressive episodes. Cycling can also occur within a month or even a 24-hour period. Rapid cycling is associated with severe symptoms and impaired functioning and is more difficult to treat.[15]

Coexisting Disorders

It is common for people with bipolar disorder to also have anxiety disorders, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, or substance use disorders.[16] Sometimes, a person with severe episodes of mania or depression may experience psychotic symptoms, such as hallucinations or delusions, resulting in an incorrect diagnosis of schizophrenia. People with bipolar disorder may misuse alcohol or drugs and engage in other high-risk behaviors in times of impaired judgment during manic episodes. In some cases, people with bipolar disorder also have an eating disorder, such as binge eating or bulimia.[17]

Physiological causes can also cause mania-like symptoms. For example, hyperthyroidism can cause difficulty sleeping, irritability, anxiety, and unintentional weight loss. Individuals can also experience substance-induced bipolar symptoms that develop during intoxication by a substance or withdrawal from a substance. For example, alcohol, sedatives, cocaine, methamphetamines, and phencyclidine (PCP) can cause bipolar-like symptoms.[18] For these reasons, on initial evaluation of a client experiencing a manic episode, screening is often typically performed for thyroid disorders and substance use.

Causes of Bipolar Disorder

Researchers continue to study the possible causes of bipolar disorder. Similar to depressive disorders, most experts agree there is no single cause, and there are many factors that contribute to bipolar disorder. Research shows that people who have a parent or sibling with bipolar disorder have genetic predisposition toward having the disorder. Some studies indicate that neurobiological factors may also predispose individuals to bipolar disorder. The brains of people with bipolar disorder may differ from the brains of people who do not have bipolar disorder. People with certain genes are more likely to develop bipolar disorder. Newer research indicates altered intracellular calcium signaling occurs in people with bipolar disorders, and antiseizure medications can provide effective treatment.[19],[20]

Environmental factors may also causative role in the development of bipolar disorders. Stress is a common trigger for mania and depression in adults, and previous adverse childhood events (ACEs) are significantly associated with bipolar disorder.[21] For example, a person with an unstable, chaotic childhood may experience bipolar disorder later in adulthood that is triggered by extreme stress. Read more about ACEs in the “Mental Health and Mental Illness” section in Chapter 1.

Read more on the National Institute of Mental Health’s Bipolar Disorder web page.

- American Psychiatric Association. (2022). Desk reference to the diagnostic criteria from DSM-5-TR (5th ed.). American Psychiatric Association Publishing. ↵

- American Psychiatric Association. (2022). Desk reference to the diagnostic criteria from DSM-5-TR (5th ed.). American Psychiatric Association Publishing. ↵

- American Psychiatric Association. (2022). Desk reference to the diagnostic criteria from DSM-5-TR (5th ed.). American Psychiatric Association Publishing. ↵

- American Psychiatric Association. (2022). Desk reference to the diagnostic criteria from DSM-5-TR (5th ed.). American Psychiatric Association Publishing. ↵

- American Psychiatric Association. (2022). Desk reference to the diagnostic criteria from DSM-5-TR (5th ed.). American Psychiatric Association Publishing. ↵

- Baldessarini, R. J., Vázquez, G. H., & Tondo, L. (2020, January 6). Bipolar depression: A major unsolved challenge. International Journal of Bipolar Disorders 8(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40345-019-0160-1 ↵

- American Psychiatric Association. (2022). Desk reference to the diagnostic criteria from DSM-5-TR (5th ed.). American Psychiatric Association Publishing. ↵

- “Bipolar_mood_shifts.png” by Osmosis is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0 ↵

- National Institute of Mental Health. (2024). Bipolar disorder. National Institutes of Health. https://www.nimh.nih.gov/health/topics/bipolar-disorder ↵

- American Psychiatric Association. (2022). Desk reference to the diagnostic criteria from DSM-5-TR (5th ed.). American Psychiatric Association Publishing. ↵

- National Institute of Mental Health. (2024). Bipolar disorder. National Institutes of Health. https://www.nimh.nih.gov/health/topics/bipolar-disorder ↵

- American Psychiatric Association. (2022). Desk reference to the diagnostic criteria from DSM-5-TR (5th ed.). American Psychiatric Association Publishing. ↵

- National Institute of Mental Health. (2024). Bipolar disorder. National Institutes of Health. https://www.nimh.nih.gov/health/topics/bipolar-disorder ↵

- American Psychiatric Association. (2022). Desk reference to the diagnostic criteria from DSM-5-TR (5th ed.). American Psychiatric Association Publishing. ↵

- Halter, M. (2022). Varcarolis’ foundations of psychiatric-mental health nursing (9th ed.). Saunders. ↵

- Hunt, G. E., Malhi, G. S., Cleary, M., Lai, H. M., & Sitharthan, T. (2016). Prevalence of comorbid bipolar and substance use disorders in clinical settings, 1990-2015: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Affective Disorders, 206, 331-349. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2016.07.011 ↵

- National Institute of Mental Health. (2023). Bipolar disorder. National Institutes of Health. https://www.nimh.nih.gov/health/topics/bipolar-disorder ↵

- American Psychiatric Association. (2022). Desk reference to the diagnostic criteria from DSM-5-TR (5th ed.). American Psychiatric Association Publishing. ↵

- National Institute of Mental Health. (2024). Bipolar disorder. National Institutes of Health. https://www.nimh.nih.gov/health/topics/bipolar-disorder ↵

- The Emerging Neurobiology of Bipolar Disorder by Harrison, Geddes, & Tunbridge is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- Halter, M. (2022). Varcarolis’ foundations of psychiatric-mental health nursing (9th ed.). Saunders. ↵

A persistently elevated or irritable mood with abnormally increased energy lasting at least one week.

A distinct period of abnormally and persistently elevated, expansive, or irritable mood, accompanied by increased activity or energy, lasting at least four consecutive days and present most of the day, nearly every day.

An episode where the person experiences a depressed mood (feeling sad, irritable, empty) or a loss of pleasure or interest in activities, for most of the day, nearly every day, for at least two weeks.

The most severe bipolar disorder with at least one manic episode; most individuals experience additional hypomanic and depressive episodes.

A pattern of depressive episodes and hypomanic episodes, but individuals have never experienced a full-blown manic episodes typical of Bipolar I Disorder.

A disorder defined by periods of hypomanic symptoms and periods of depressive symptoms lasting for at least two years (1 year in children and adolescents).

At least four mood episodes associated with bipolar disorder occurring in a 12-month period.