7.3 Types of Depression

Depression is different from the usual mood fluctuations and short-lived emotional responses to everyday life stressors. When it is recurrent with moderate or severe intensity, depression can become a serious health condition that causes the affected person to suffer greatly and function poorly at work and school and can affect relationships with family and friends. At its worst, depression can lead to suicide. Over 700,000 people die every year due to suicide. Barriers to effective care for depression include a lack of resources, lack of trained health care providers, and social stigma associated with mental health disorders.[1] Depressive disorders represent a group of conditions that share a core set of symptoms but differ in important ways such as duration, timing, triggers, and presumed causes (etiology). The common feature across all depressive disorders is the presence of a sad, empty, or irritable mood that is accompanied by physical (somatic) and mental (cognitive) changes. These changes significantly impair a person’s ability to function in daily life—impacting work, relationships, self-care, and overall quality of life. See Figure 7.5[2] for an artistic depiction of an individual experiencing depression.

Major Depressive Disorder

A major depressive episode is a period of at least two weeks during which a person experiences a persistently depressed mood or a loss of interest or pleasure in nearly all activities, most of the day, nearly every day. This emotional state is accompanied by additional symptoms such as changes in appetite or weight, sleep disturbances (insomnia or sleeping too much), fatigue or loss of energy, feelings of worthlessness or excessive guilt, difficulty concentrating or making decisions, and recurrent thoughts of death or suicide. During a depressive episode, the person experiences a depressed mood (feeling sad, irritable, empty) or a loss of pleasure or interest in activities (anhedonia) for most of the day, nearly every day, for at least two weeks. Several other symptoms may also be present, which may include poor concentration, feelings of excessive guilt or low self-worth, hopelessness about the future, thoughts about dying or suicide, disrupted sleep, changes in appetite or weight, and feeling especially tired or low in energy. In some cultural contexts, some people may express their mood changes more readily in the form of bodily symptoms (such as pain, fatigue, or weakness) that are not due to another medical condition. During a depressive episode, the person experiences significant difficulty and/or impairment in important areas of personal, family, social, educational, and work functioning.[3]

A depressive episode is categorized by a provider as mild, moderate, or severe depending on the number and severity of symptoms, as well as the impact on the individual’s functioning.[4] Mild severity indicates the symptoms to make the diagnosis are present but result in minor impairment in social or occupational functioning. Moderate severity indicates symptoms and impairment are between mild and severe. Severe indicates the intensity is seriously distressing, unmanageable, and markedly interferes with social and occupational functioning. Read the full list of criteria for Major Depressive Disorder from the DSM-5-TR in the following box.

DSM-5-TR Criteria for Major Depressive Disorder[5]

- Five or more of the following symptoms have been present during the same two-week period and represent a change from previous functioning; at least one of the symptoms is either (1) depressed mood or (2) loss of interest or pleasure.

- Depressed mood most of the day, nearly every day, as indicated by either subjective report (e.g., feels sad, empty, hopeless) or observation made by others (e.g., appears tearful). (Note: In children and adolescents, can be irritable mood.)

- Markedly diminished interest or pleasure in all, or almost all, activities most of the day, nearly every day.

- Significant weight loss when not dieting or weight gain (i.e., a change of more than 5% of body weight in a month) or decrease or increase in appetite nearly every day. (Note: In children, consider failure to make expected weight gain.)

- Insomnia or hypersomnia nearly every day.

- Psychomotor agitation or retardation nearly every day (observable by others, not merely subjective feelings of restlessness or being slowed down).

- Fatigue or loss of energy nearly every day.

- Feelings of worthlessness or excessive or inappropriate guilt (which may be delusional) nearly every day (not merely self-reproach or guilt about being sick).

- Diminished ability to think or concentrate, or indecisiveness, nearly every day (either by subjective account or as observed by others).

- Recurrent thoughts of death (not just fear of dying), recurrent suicidal ideation without a specific plan, or a suicide attempt or a specific plan for committing suicide.

- The symptoms cause clinically significant distress or impairment in social, occupational, or other important areas of functioning.

- The episode is not attributable to the physiological effects of a substance or another medical condition.

- The client has never had a manic or hypomanic episode.

Seasonal Pattern

Seasonal affective disorder (SAD) is a type of major depressive disorder that affects about 5% of adults in the United States. People with SAD experience mood changes and symptoms similar to depression. The symptoms usually occur during the fall and winter months when there is less sunlight and usually improve with the arrival of spring. SAD is more than just “winter blues.” The symptoms can be distressing and overwhelming and can interfere with daily functioning.[6]

SAD has been linked to a biochemical imbalance in the brain prompted by shorter daylight hours and less sunlight in winter. As seasons change, people experience a shift in their biological internal clock or circadian rhythm that can cause them to be out of step with their daily schedule. SAD is more common in people living far from the equator where there are fewer daylight hours in the winter.[7]

SAD can be effectively treated with light therapy, antidepressant medications, cognitive behavioral therapy, or some combination of these. While symptoms will generally improve on their own with the change of season, symptoms can improve more quickly with treatment. Light therapy involves sitting in front of a light therapy box that emits a very bright light (and filters out harmful ultraviolet [UV] rays). Bright light therapy typically involves exposure to a light box emitting 2,500 to 10,000 lx of light.[8] It usually requires 20 minutes or more per day, typically first thing in the morning during the winter months. Most people see some improvements from light therapy within one or two weeks of beginning treatment. For some people, increased exposure to natural sunlight can help improve symptoms of SAD by spending time outside or arranging their home or office space to increase exposure to windows during daylight hours. General wellness activities such as performing regular exercise, eating healthfully, getting enough sleep, and staying active and connected (such as volunteering, participating in group activities and getting together with friends and family) can also help.[9]

Peripartum Onset

Pregnancy and the time following childbirth represent a uniquely vulnerable period for women. This phase of life often involves intense biological changes, emotional adjustments, financial pressures, and shifting social roles. These stressors can have a profound impact on a woman’s mental health, potentially resulting in a spectrum of mood disturbances—from mild and temporary feelings of sadness to more severe depressive disorders that may require clinical intervention.

Baby Blues

It is common for new mothers to experience what is known as the “baby blues,” which affects up to 70% of women after childbirth. The baby blues typically begin within a few days of delivery and include emotional lability, tearfulness without an obvious cause, mild irritability, restlessness, and a general sense of anxiety or being overwhelmed. These symptoms are usually mild, self-limited, and do not interfere significantly with a mother’s ability to care for herself or her baby. Most cases resolve spontaneously within about two weeks, and medical treatment is generally not necessary.

Perinatal Depression

Perinatal depression represents a more serious mental health condition. Perinatal depression is a broad term that refers to depressive symptoms that occur any time during pregnancy and up to one year after childbirth. This includes both antenatal (or prenatal) depression, which develops while the person is still pregnant, and postpartum depression, which occurs after the baby is born. Perinatal depression can affect emotional well-being, physical health, bonding with the baby, and overall family functioning. It is more than just occasional sadness or stress. Symptoms of perinatal depression often include persistent feelings of sadness, anxiety, fatigue, irritability, changes in sleep and appetite, and difficulty concentrating or feeling connected to the baby.[10]

Postpartum Depression

Postpartum depression is a subset of perinatal depression and refers to a major depressive episode that begins after childbirth. It is much more serious mental health condition than the “baby blues.” Postpartum depression is characterized by persistent feelings of sadness, hopelessness, anxiety, and exhaustion that interfere with a mother’s ability to function and care for her infant. These symptoms go beyond the scope of the baby blues in both intensity and duration, often requiring professional treatment such as psychotherapy, medication, or a combination of both. If left untreated, postpartum depression can significantly impair the mother–infant bond, contribute to difficulties with infant feeding and sleeping, and may have long-term consequences for the child’s emotional, cognitive, and social development. Symptoms of postpartum depression usually start between one to three weeks after birth.[11] These symptoms reflect the same characteristics as those in the perinatal depression group, yet the time of onset is different. Many health care providers recognize that postpartum depression can emerge at any point within the first year following childbirth, even though this extended timeframe is not explicitly captured in DSM-5-TR criteria.

In rare and severe cases, postpartum depression may escalate into a condition called postpartum psychosis. This is a psychiatric emergency that requires immediate medical intervention. Postpartum psychosis can involve hallucinations, delusions, disorganized thinking, mania, severe agitation, and confusion. Because of the potential risk for self-harm or harm to the infant, individuals experiencing symptoms of postpartum psychosis should be brought to the nearest emergency room or emergency services should be contacted immediately.

Understanding the range and severity of mood disorders related to pregnancy and childbirth is essential for early identification and intervention. Prompt recognition and appropriate care can significantly improve outcomes for both the mother and her child.

Pregnancy and the period after delivery can be a vulnerable time for women. Mothers can experience significant biological, emotional, financial, and social changes during this time. Up to 70 percent of new mothers experience the “baby blues,” a short-term condition that does not interfere with their daily activities and does not require medical attention. Symptoms include crying for no reason, irritability, restlessness, and anxiety. These symptoms generally last up to two weeks and resolve on their own.[12]

See Figure 7.6[13] for an illustration of perinatal depression from the National Institutes of Health.

Untreated peripartum depression is not only a problem for the mother’s health and quality of life but can also affect the well-being of the baby. Postpartum depression can cause bonding issues with the baby and also contribute to sleeping and feeding problems for the baby. In the long-term, children of mothers with peripartum depression are at greater risk for cognitive, emotional, developmental and verbal deficits, and impaired social skills.[14]

Read more information about perinatal depression on the National Institute of Mental Health’s Perinatal Depression web page.

Persistent Depressive Disorder

Persistent depressive disorder, previously known as dysthymia, is a chronic form of depression that is typically less severe in intensity than major depressive disorder but lasts much longer. In adults, symptoms must be present for most of the day, more days than not, for at least two years. In children and adolescents, the required duration is at least one year, and the mood may be irritable rather than depressed. Individuals with this disorder often describe themselves as feeling “down in the dumps,” “low,” or “just not themselves.” Because the symptoms are milder and may develop gradually, they can become part of a person’s normal daily experience, leading many to believe their persistent low mood is simply part of their personality rather than a treatable mental health condition.[15]

Common features of persistent depressive disorder include poor appetite or overeating, insomnia or hypersomnia, low energy or fatigue, low self-esteem, poor concentration or difficulty making decisions, and feelings of hopelessness. While these symptoms may not be as intense as those seen in a major depressive episode, they can still significantly affect a person’s functioning and quality of life over time.[16]

Because the condition is long-lasting, it can interfere with relationships, work or school responsibilities, and the ability to enjoy life. Treatment often includes a combination of psychotherapy, such as cognitive behavioral therapy, and antidepressant medications like SSRIs or SNRIs. Ongoing support and follow-up care are important, as the chronic nature of the disorder requires long-term management to help individuals regain and maintain emotional well-being.[17]

Premenstrual Dysphoric Disorder

Premenstrual dysphoric disorder (PMDD) is a severe and disabling form of premenstrual syndrome (PMS) that involves significant mood disturbances and physical symptoms occurring in the final week before menstruation. While many individuals experience some degree of emotional or physical discomfort during their menstrual cycle, PMDD is much more intense and can seriously interfere with daily life, relationships, and functioning. The symptoms become minimal or absent in the week post-menses.[18]

Individuals with PMDD must have one or more of the following symptoms[19]:

- Extreme affective lability (mood swings, feeling suddenly sad or tearful, or increased sensitivity to rejection)

- Significant irritability or anger or increased interpersonal conflicts

- Significant depressed mood, feelings of hopelessness, or self-deprecating thoughts

- Significant anxiety, tension, or feelings of being keyed up or on edge.

One or more of the following symptoms must be additionally present to reach a total of five symptoms when combined with the symptoms in the preceding paragraph[20]:

- Decreased interest in usual activities (e.g., work, school, friends, hobbies)

- Difficulty concentrating

- Lethargy, easy fatigability, or significant lack of energy

- Significant change in appetite, overeating, or specific food cravings

- Hypersomnia or insomnia

- A sense of being overwhelmed or out of control

- Physical symptoms such as breast tenderness or swelling, joint or muscle pain, a sense of bloating, or weight gain

A key feature of PMDD is that these symptoms are not merely uncomfortable—they are severe enough to disrupt work, school, and personal relationships, and they go beyond what is typically expected in PMS.[21]

The exact cause of PMDD is not fully understood, but it is believed to be related to sensitivity to normal hormonal fluctuations during the menstrual cycle, particularly in individuals with an underlying vulnerability to mood disorders. Treatment may involve a combination of antidepressant medications, birth control hormonal medications, psychotherapy (especially cognitive behavioral therapy), and lifestyle modifications such as regular exercise, vitamin supplementation with B-6 and magnesium, and adaptive coping strategies such as yoga and meditation.[22]

Substance/Medication-Induced Depressive Disorder

Substance/medication-induced depressive disorder is a type of depression that occurs as a direct result of using, misusing, or withdrawing from certain substances or medications. This disorder is diagnosed when depressive symptoms such as a persistently low mood, lack of interest or pleasure, fatigue, difficulty concentrating, and feelings of worthlessness are closely linked to the use of a particular drug or substance and not better explained by another mental health condition. The depressive symptoms typically develop during or soon after substance use or withdrawal and must cause significant distress or impairment in daily functioning.[23]

A wide range of substances can trigger this disorder. Common examples include alcohol, cannabis, opioids, sedatives, stimulants, and hallucinogens, as well as prescription medications such as corticosteroids, antihypertensives, hormonal contraceptives, barbiturates, and certain antiepileptic drugs. The effects may occur in people who are taking the substance as prescribed or in those who are misusing it. In some cases, individuals may not realize that their depressive symptoms are linked to a medication or drug, especially if the symptoms have developed gradually.[24]

An important part of diagnosing this condition is establishing the temporal relationship between substance use and the onset of depression. Once the substance is discontinued or the medication is adjusted, symptoms may improve—though in some cases, clinical treatment is still necessary to help manage mood changes. Treatment involves identifying and stopping the responsible substance, providing emotional support, and in some cases, using antidepressant medications or therapy to help stabilize mood during recovery.[25]

Depressive Disorder Due to Another Medical Condition

Depressive disorder due to another medical condition is diagnosed when a person experiences a persistent depressed mood or a significant loss of interest or pleasure in activities, and these symptoms are directly caused by a medical illness or condition. Unlike other types of depression, this disorder is not primarily psychological in origin—it results from the physiological effects of a medical issue. The depressive symptoms must cause significant distress or impair the person’s ability to function in daily life.[26]

Common medical conditions associated with this type of depression include neurological disorders (such as stroke, Parkinson’s disease, multiple sclerosis), endocrine disorders (like hypothyroidism or Cushing’s disease), and chronic illnesses (such as cancer, diabetes, or heart disease). The timing of symptom onset is important for diagnosis, as the depressive symptoms must clearly follow the development of the medical condition and not be better explained by another mental health disorder.[27]

Treatment involves addressing both the underlying medical condition and the depressive symptoms, which may include psychotherapy, medication, or supportive care depending on the individual’s needs.[28]

Mixed Features

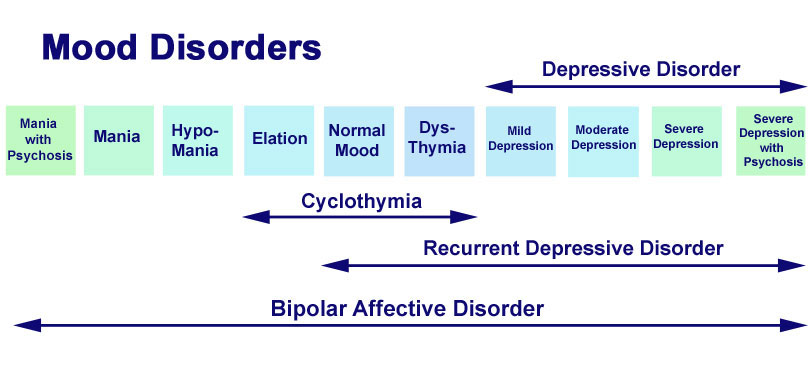

Depressive episodes can also be classified as “mixed,” meaning symptoms are present but do not predominate.[29] Mixed features associated with a major depressive episode have been found to be a significant risk factor for the development of Bipolar I or Bipolar II disorder. Characteristics and treatment of bipolar disorder are further discussed in the “Bipolar Disorders” chapter.

See Figure 7.7[30] for a comparison of the features of different types of mood disorders.

Read more information at the American Psychiatric Association’s What is Depression? web page.

Listen to The Dark Place podcast on the Podbean website to hear personal perspectives on depression and other mental health topics.

View the following YouTube video of an advocate explaining her experiences with depression and her journey to recovery[31]:

Grief

Individuals often have difficulty coping with the death or loss of a loved one, job, or relationship. It is normal for feelings of sadness or grief to develop in response to such situations, but these symptoms are not the same as having a major depressive disorder. The grieving process is natural and unique to each individual and shares some of the same features of depression. Both grief and depression can involve intense sadness and withdrawal from usual activities with increased risk for suicide.

According to the American Psychiatric Association, grief and depression are different in these ways[32]:

- In grief, painful feelings come in waves, often intermixed with positive memories of the deceased. In major depression, mood and/or interest (pleasure) are decreased for most of two weeks.

- In grief, one’s self-esteem is usually maintained. In major depression, feelings of worthlessness and self-loathing are common.

- In grief, thoughts of death may surface when thinking of or fantasizing about “joining” the deceased loved one. In major depression, thoughts are focused on ending one’s life due to feeling worthless or undeserving of living or being unable to cope with the pain of depression.

Prolonged Grief Disorder

The DSM-5-TR introduced a new diagnosis called prolonged grief disorder that is characterized by intense longing and preoccupation with the deceased person that persists beyond 12 months and causes significant impairment. Additionally, since the death, at least three of the following symptoms are present[33]:

- Identity disruption (e.g., feeling as though part of oneself has died) since the death

- Significant sense of disbelief about the death

- Avoidance of reminders that the person is dead

- Intense emotional pain related to the death

- Difficulty reintegrating into one’s relationships and activities after the death

- Emotional numbness as a result of the death

- Feeling that life is meaningless as a result of the death

- Intense loneliness as a result of the death

Read more information about grief in the “Grief and Loss” chapter in Open RN Nursing Fundamentals, 2e.

- World Health Organization. (2021). Depression. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/depression ↵

- “320531.png” by j4p4n at openclipart.org is licensed in the Public Domain. ↵

- World Health Organization. (2021). Depression. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/depression ↵

- World Health Organization. (2021). Depression. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/depression ↵

- American Psychiatric Association. (2022). Desk reference to the diagnostic criteria from DSM-5-TR (5th ed.). American Psychiatric Association Publishing. ↵

- American Psychiatric Association. (2020). Seasonal affective disorder (SAD). https://www.psychiatry.org/patients-families/depression/seasonal-affective-disorder ↵

- American Psychiatric Association. (2020). Seasonal affective disorder (SAD). https://www.psychiatry.org/patients-families/depression/seasonal-affective-disorder ↵

- Pjrek, E., Friedrich, M.E., Cambioli, L., Dold, M., Jäger, F., Komorowski, A., Lanzenberger, R., Kasper, S, & Winkler, D. (2020). The efficacy of light therapy in the treatment of seasonal affective disorder: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Psychotherapy Psychosomatics, 89(1), 17-24. doi: 10.1159/000502891. ↵

- American Psychiatric Association. (2020). Seasonal affective disorder (SAD). https://www.psychiatry.org/patients-families/depression/seasonal-affective-disorder ↵

- National Institute of Mental Health (2023). Perinatal depression. https://www.nimh.nih.gov/health/publications/perinatal-depression ↵

- National Library of Medicine. (2022). Postpartum depression screening. https://medlineplus.gov/lab-tests/postpartum-depression-screening/ ↵

- American Psychiatric Association (2020). What is peripartum depression (formerly postpartum)? https://www.psychiatry.org/patients-families/postpartum-depression/what-is-postpartum-depression ↵

- This image is a derivative of “20-mh-8116-perinataldepression.pdf” by National Institute of Mental Health and is licensed in the Public Domain. Access for free at https://www.nimh.nih.gov/health/publications/perinatal-depression. ↵

- American Psychiatric Association (2020). What is peripartum depression (formerly postpartum)? https://www.psychiatry.org/patients-families/postpartum-depression/what-is-postpartum-depression ↵

- American Psychiatric Association. (2022). Desk reference to the diagnostic criteria from DSM-5-TR (5th ed.). American Psychiatric Association Publishing. ↵

- American Psychiatric Association. (2022). Desk reference to the diagnostic criteria from DSM-5-TR (5th ed.). American Psychiatric Association Publishing. ↵

- American Psychiatric Association. (2022). Desk reference to the diagnostic criteria from DSM-5-TR (5th ed.). American Psychiatric Association Publishing. ↵

- American Psychiatric Association. (2022). Desk reference to the diagnostic criteria from DSM-5-TR (5th ed.). American Psychiatric Association Publishing. ↵

- American Psychiatric Association. (2022). Desk reference to the diagnostic criteria from DSM-5-TR (5th ed.). American Psychiatric Association Publishing. ↵

- American Psychiatric Association. (2022). Desk reference to the diagnostic criteria from DSM-5-TR (5th ed.). American Psychiatric Association Publishing. ↵

- American Psychiatric Association. (2022). Desk reference to the diagnostic criteria from DSM-5-TR (5th ed.). American Psychiatric Association Publishing. ↵

- Cleveland Clinic. (2023). Premenstrual dysphoric disorder. https://my.clevelandclinic.org/health/diseases/9132-premenstrual-dysphoric-disorder-pmdd ↵

- American Psychiatric Association. (2022). Desk reference to the diagnostic criteria from DSM-5-TR (5th ed.). American Psychiatric Association Publishing. ↵

- American Psychiatric Association. (2022). Desk reference to the diagnostic criteria from DSM-5-TR (5th ed.). American Psychiatric Association Publishing. ↵

- American Psychiatric Association. (2022). Desk reference to the diagnostic criteria from DSM-5-TR (5th ed.). American Psychiatric Association Publishing. ↵

- American Psychiatric Association. (2022). Desk reference to the diagnostic criteria from DSM-5-TR (5th ed.). American Psychiatric Association Publishing. ↵

- American Psychiatric Association. (2022). Desk reference to the diagnostic criteria from DSM-5-TR (5th ed.). American Psychiatric Association Publishing. ↵

- American Psychiatric Association. (2022). Desk reference to the diagnostic criteria from DSM-5-TR (5th ed.). American Psychiatric Association Publishing. ↵

- American Psychiatric Association. (2022). Desk reference to the diagnostic criteria from DSM-5-TR (5th ed.). American Psychiatric Association Publishing. ↵

- “mood-disorders.jpg” by Dr. Vipul Rastogi, MBBS; DCP (Ireland); MRCPsych (UK) Speciality Registrar, Hampshire Partnership Trust, UK for www.clinicaljunior.com. Image used under Fair Use. Access for free at http://www.clinicaljunior.com/psychmoodvipul.html ↵

- World Health Organization (WHO). (2018, September 19). Youth voices: Kylie Verzosa on depression [Video]. YouTube. Licensed in the Public Domain. https://youtu.be/tRc4XZXYTgY ↵

- American Psychiatric Association. (2020). What is depression? https://www.psychiatry.org/patients-families/depression/what-is-depression ↵

- American Psychiatric Association. (2022). Desk reference to the diagnostic criteria from DSM-5-TR (5th ed.). American Psychiatric Association Publishing. ↵

A period of at least two weeks during which a person experiences a persistently depressed mood or a loss of interest or pleasure in nearly all activities, most of the day, nearly every day.

An episode where the person experiences a depressed mood (feeling sad, irritable, empty) or a loss of pleasure or interest in activities, for most of the day, nearly every day, for at least two weeks.

A type of depression causing symptoms during the fall and winter months when there is less sunlight and usually improves with the arrival of spring.

Therapy for seasonal affective disorder (SAD) that involves sitting in front of a light therapy box that emits a very bright light. It usually requires 20 minutes or more per day, typically first thing in the morning, during the winter months.

Depressive disorder that occurs during pregnancy.

Feelings of extreme sadness, anxiety, and exhaustion that may make it difficult for mothers of newborns to complete daily care activities for themselves and/or for their babies.

A chronic form of depression that is typically less severe in intensity than Major Depressive Disorder but lasts much longer.

A severe and disabling form of premenstrual syndrome (PMS) that involves significant mood disturbances and physical symptoms occurring in the week or two before menstruation.

A type of depression that occurs as a direct result of using, misusing, or withdrawing from certain substances or medications.

When a person experiences a persistent depressed mood or a significant loss of interest or pleasure in activities, and these symptoms are directly caused by a medical illness or condition.

Intense longing and preoccupation with the deceased person that persists beyond 12 months and causes significant impairment.