3.2 Stress

Everyone experiences stress during their lives. High levels of stress can cause symptoms like headaches, back pain, and gastrointestinal symptoms. Chronic stress can contribute to the development of chronic illnesses, as well as acute physical illnesses, due to decreased effectiveness of the immune system and impact on the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis. The HPA impact is discussed in greater detail below. It is important for nurses to recognize signs and symptoms of stress in themselves and others, as well as encourage effective stress management strategies. This section begins with an overview of the stress response and its signs and symptoms, followed by a discussion of stress management techniques.

We will begin this section by reviewing the stress response and signs and symptoms of stress and then discuss stress management techniques.

Stress Response

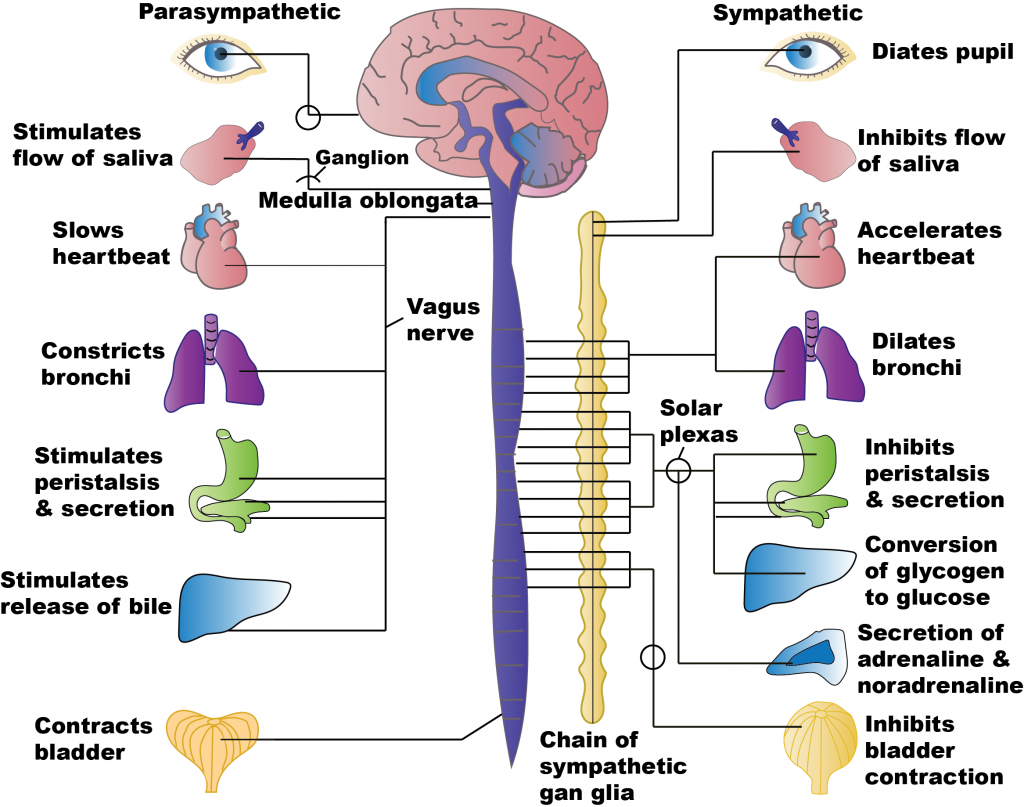

Stressors are any internal or external event, force, or condition that results in physical or emotional stress.[1] The body’s sympathetic nervous system (SNS) responds to actual or perceived stressors with the “fight, flight, freeze, or fawn” stress response. Several reactions occur during the stress response that help the individual to achieve the purpose of either fighting or running.

Several physiological changes occur:

- The respiratory, cardiovascular, and musculoskeletal systems activate to increase breathing, heart rate, and blood pressure, ensuring oxygenated blood reaches the muscles.

- The liver releases glucose to provide energy for immediate action.

- Pupils dilate to enhance vision.

- Sweating prevents overheating due to increased muscle activity.

- The digestive system slows, redirecting blood flow to essential muscles.

These responses are coordinated by the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis, which releases hormones like epinephrine, norepinephrine, and glucocorticoids (including cortisol, the “stress hormone”). These hormones target SNS receptors throughout the body, ensuring a rapid, systemic reaction.[2]

In the “fawn” response, which is particularly common in individuals exposed to relational trauma, the body may still activate stress-related pathways, but the behavioral focus shifts toward pleasing or placating others to prevent harm. Though less visibly physical, fawning is still driven by the same biological systems seeking safety in a perceived threat.

Once the threat subsides, the parasympathetic nervous system (PNS) counteracts the SNS, restoring the body to its pre-stress state. See Figure 3.1 for a comparison of SNS and PNS effects.

Signs and Symptoms of Chronic Stress

Nurses are often the first to notice signs and symptoms of stress and can help make their clients aware of these symptoms. Common signs and symptoms of chronic stress are as follows[3],[4]:

- Irritability

- Fatigue

- Headaches

- Difficulty concentrating

- Rapid, disorganized thoughts

- Difficulty sleeping

- Digestive problems

- Changes in appetite

- Feeling helpless

- A perceived loss of control

- Low self-esteem

- Loss of sexual desire

- Nervousness

- Frequent infections or illnesses

- Vocalized suicidal thoughts

Effects of Chronic Stress

The “fight or flight or freeze” stress response prepares the body to react quickly to immediate threats. However, exposure to long-term stress can cause serious effects on the cardiovascular, musculoskeletal, endocrine, gastrointestinal, and reproductive systems.[5]

Cardiovascular System: Sustained increases in heart rate, blood pressure, and stress hormones contribute to arterial inflammation, raising the risk of hypertension, heart attack, and stroke.[6]

Musculoskeletal System: During acute stress, muscles tense and relax once the threat passes. However, chronic stress keeps muscles in a constant state of tension, which may contribute to stress-related disorders. For example tension and migraine headaches are linked to persistent muscle tightness in the shoulders, neck, and head. Musculoskeletal pain in the lower back and upper extremities has been associated with job-related stress.[7]

Endocrine & Immune Systems: In acute stress, cortisol provides energy to cope with immediate challenges. However, chronic stress weakens the immune system, increasing susceptibility to conditions such as chronic fatigue, metabolic disorders (e.g., diabetes, obesity), depression, and immune dysfunction.[8]

Gastrointestinal System: Chronic stress can disrupt eating patterns, leading to eating much more or much less than usual. It may also cause the following:

- Acid reflux, often due to increased consumption of food, alcohol, or tobacco.

- Bowel irregularities—stress can induce muscle spasms in the bowel and affect how quickly food moves through the gastrointestinal system, leading to diarrhea or constipation.

- Aggravation of chronic gastrointestinal disorders (e.g., inflammatory bowel disease, irritable bowel syndrome) due to factors such as increased nerve sensitivity, disturbed microbiota, altered gastrointestinal motility, and/or disrupted immune function.[9]

Reproductive System: Excess cortisol can disrupt normal reproductive function in both men and women.

- Men: Chronic stress can affect testosterone production, resulting in the following:

- Reduced libido, erectile dysfunction, or impotence.

- Impaired sperm production and maturation.

- Decreased sperm quality—studies indicate that, compared to men who did not experience stressful events in the past year, those who experienced two or more stressful events within the same period had the following:

- Lower sperm motility.

- A reduced percentage of sperm with normal morphology (size and shape).[10]

- Women: Chronic stress can affect reproductive health, leading to the following:

- Menstrual irregularities, including absent or irregular cycles, more painful periods, and changes in cycle length.

- Worsened premenstrual symptoms, such as cramping, fluid retention, bloating, negative mood, and mood swings.

- Reduced sexual desire.

- Impaired fertility and pregnancy health—stress can negatively impact:

- A woman’s ability to conceive.

- Pregnancy health and postpartum recovery.

- Fetal development.

- Maternal-infant bonding following delivery.

- The risk of postpartum depression.[11]

Adverse Childhood Experiences

Adults with adverse childhood experiences or exposure to adverse life events often experience ongoing chronic stress with an array of physical, mental, and social health problems throughout adulthood. Some of the most common health risks include physical and mental illness, substance use disorder, and a high level of engagement in risky sexual behavior.[12]

As previously discussed in Chapter 1, adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) include sexual abuse, physical abuse, emotional abuse, physical neglect, emotional neglect, parental loss, or parental separation before the child is 18 years old. Individuals who have experienced four or more ACEs are at a significantly higher risk of developing mental, physical, and social problems in adulthood. Research has established that early life stress is a predictor of smoking, alcohol consumption, and drug dependence. Adults who experienced ACEs related to maladaptive family functioning (parental mental illness, substance use disorder, criminality, family violence, physical and sexual abuse, and neglect) are at higher risk for developing mood, substance abuse, and anxiety disorders. ACEs are also associated with an increased risk of the development of malignancy, cardiovascular disease, metabolic syndrome, and other chronic debilitating conditions.[13]

Stress Management

Recognizing signs and symptoms of stress allows individuals to implement stress management strategies. Nurses can educate clients about effective strategies for reducing the stress response. Relaxation techniques and other stress-relieving activities have been shown to effectively reduce muscle tension, decrease the incidence of stress-related disorders, and increase a sense of well-being. For individuals with chronic pain conditions, stress-relieving activities have been shown to improve mood and daily function.[14] Effective strategies include the following[15],[16]:

- Set personal and professional boundaries

- Maintain a healthy social support network

- Select healthy food choices

- Engage in regular physical exercise

- Get an adequate amount of sleep each night

- Set realistic and fair expectations

- Mindfulness activities

Setting limits is essential for effectively managing stress. Individuals should list all of the projects and commitments making them feel overwhelmed, identify essential tasks, and cut back on nonessential tasks. For work-related projects, responsibilities can be discussed with supervisors to obtain input on priorities. Encourage individuals to refrain from accepting any more commitments until they feel their stress is under control.[17]

Maintaining a healthy social support network with friends and family can provide emotional support.[18] Caring relationships and healthy social connections are essential for achieving resilience.

Eating nutritiously is a valuable tool in stress management. Clients should be taught to eat at regular intervals to ensure steady blood glucose levels to ensure optimal performance. Foods high in fatty acids, such as nuts and fish oil, can help combat anxiety and depression. Foods that are high in vitamins and minerals, such as leafy greens, can also work to combat stress. A diet that is high in fiber has also been shown to result in lower perceived levels of stress. Additionally, caffeine should be avoided as it can heighten anxiety. Lastly, prepare for stress- inducing or hectic times by ensuring that high-nutrient food is readily available. Good options are hummus with carrots, yogurt with granola, or fruit and cheese.[19]

Physical activity increases the body’s production of endorphins that boost the mood and reduce stress. Nurses can educate clients that a brisk walk or other aerobic activity can increase energy and concentration levels and lessen feelings of anxiety.[20]

People who are chronically stressed often suffer from lack of adequate sleep and, in some cases, stress-induced insomnia. Nurses can educate individuals how to take steps to increase the quality of sleep. Experts recommend going to bed at a regular time each night, striving for at least seven to eight hours of sleep, and, if possible, eliminating distractions, such as television, cell phones, and computers from the bedroom. Begin winding down an hour or two before bedtime and engage in calming activities such as listening to relaxing music, reading an enjoyable book, taking a soothing bath, or practicing relaxation techniques like meditation. Avoid eating a heavy meal or engaging in intense exercise immediately before bedtime. If a person tends to lie in bed worrying, encourage them to write down their concerns and work on quieting their thoughts.[21] For many individuals, sleeping in a cool room facilitates sleep.

Nurses can encourage clients to set realistic expectations, look at situations more positively, see problems as opportunities, and refute negative thoughts to stay positive and minimize stress. Setting realistic expectations and positively reframing the way one looks at stressful situations can make life seem more manageable. Clients should be encouraged to keep challenges in perspective and do what they can reasonably do to move forward.[22]

Mindfulness is a form of meditation that uses breathing and thought techniques to create an awareness of one’s body and surroundings. Research suggests that mindfulness can have a positive impact on stress, anxiety, and depression.[23] Additionally, guided imagery may be helpful for enhancing relaxation. The use of guided imagery provides a narration that the mind can focus on during the activity. For example, as the nurse encourages a client to use mindfulness and relaxation breathing, they may say, “As you breathe in, imagine waves rolling gently in. As you breathe out, imagine the waves rolling gently back out to sea.” Read more about mindfulness techniques in the “Coping” section of this chapter.

WHO Stress Management Guide

In addition to the stress management techniques discussed in the previous subsection, the World Health Organization (WHO) shares additional techniques in a guide titled Doing What Matters in Times of Stress. This guide is consists of five categories. Each category includes techniques and skills that, based on evidence and field testing, can reduce overall stress levels even if only used for a few minutes each day. These categories include 1) Grounding, 2) Unhooking, 3) Acting on our values, 4) Being kind, and 5) Making room.[24]

Nurses can educate clients that powerful thoughts and feelings are a natural part of stress, but problems can occur if we get “hooked” by them. For example, one minute you might be enjoying a meal with family, and the next moment you get “hooked” by angry thoughts and feelings. Stress can make someone feel as if they are being pulled away from the values of the person they want to be, such as being calm, caring, attentive, committed, persistent, and courageous.[25]

There are many kinds of difficult thoughts and feelings that can “hook us,” such as, “This is too hard,” “I give up,” “I am never going to get this,” “They shouldn’t have done that,” or memories about difficult events that have occurred in our lives. When we get “hooked,” our behavior changes. We may do things that make our lives worse, like getting into more disagreements, withdrawing from others, or spending too much time lying in bed. These are called “away moves” because they move us away from our values. Sometimes emotions become so strong they feel like emotional storms. However, we can “unhook” ourselves by focusing and engaging in what we are doing, referred to as “grounding.”[26]

Grounding

“Grounding” is a helpful tool when feeling distracted or having trouble focusing on a task and/or the present moment. The first step of grounding is to notice how you are feeling and what you are thinking. Next, slow down and connect with your body by focusing on your breathing. Exhale completely and wait three seconds, and then inhale as slowly as possible. Slowly stretch your arms and legs and push your feet against the floor. The next step is to focus on the world around you. Notice where you are and what you are doing. Use your five senses. What are five things you can see? What are four things you can hear? What can you smell? Tap your leg or squeeze your thumb and count to ten. Touch your knees or another object within reach. What does it feel like? Grounding helps us engage in life, refocus on the present moment, and realign with our values.[27]

Unhooking

At times we may have unwanted, intrusive, negative thoughts that negatively affect us. “Unhooking” is a tool to manage and decrease the impact of these unwanted thoughts. First, NOTICE that a thought or feeling has hooked you, and then NAME it. Naming it begins by silently saying, “Here is a thought,” or “Here is a feeling.” By adding “I notice,” it unhooks us even more. For example, “I notice there is a knot in my stomach.” The next step is to REFOCUS on what you are doing, fully engage in that activity, and pay full attention to whoever is with you and whatever you are doing. For example, if you are having dinner with family and notice feelings of anger, note “I am having feelings of anger,” but choose to refocus and engage with family.[28]

Acting on Our Values

The third category of skills is called “Acting on Our Values.” This means, despite challenges and struggles we are experiencing, we will act in line with what is important to us and our beliefs. Even when facing difficult situations, we can still make the conscious choice to act in line with our values. The more we focus on our own actions, the more we can influence our immediate world and the people and situations we encounter every day. We must continually ask ourselves, “Are my actions moving me toward or away from my values?” Remember that even the smallest actions have impact, just as a giant tree grows from a small seed. Even in the most stressful of times, we can take small actions to live by our values and maintain or create a more satisfying and fulfilling life. These values should also include self-compassion and care. By caring for oneself, we ultimately have more energy and motivation to then help others.[29]

Being Kind

“Being Kind” is a fourth tool for reducing stress. Kindness can make a significant difference to our mental health by being kind to others, as well as to ourselves. Being kind to others helps build strong relationships, which makes people happier and more resilient. Studies show that people who are kind tend to live longer and have better health. Acts of kindness benefit both the person giving and receiving them. Even just witnessing kindness can make people feel good and encourage them to be more kind themselves. It creates a positive cycle of connection and caring within communities.[30]

Making Room

“Making Room” is a fifth tool for reducing stress. Sometimes trying to push away painful thoughts and feelings does not work very well. In these situations, it is helpful to notice and name the feeling, and then “make room” for it. “Making room” means allowing the painful feeling or thought to come and go like the weather. Nurses can educate clients that as they breathe, they should imagine their breath flowing into and around their pain and making room for it. Instead of fighting with the thought or feeling, they should allow it to move through them, just like the weather moves through the sky. If clients are not fighting with the painful thought or feeling, they will have more time and energy to engage with the world around them and do things that are important to them.[31]

Read Doing What Matters in Times of Stress by the World Health Organization (WHO).[32]

View the following YouTube video on the WHO stress management guide[33]:

Stress Related to the COVID-19 Pandemic and World Events

The COVID-19 pandemic had a major effect on many people’s lives. Many health care professionals faced challenges that were stressful, overwhelming, and caused strong emotions.[34] See Figure 3.2[35] for a message from the World Health Organization regarding stress and health care workers.

Learning to cope with stress in a healthy way can increase feelings of resiliency for health care professionals. Here are ways to help manage stress resulting from world events[36]:

- Take breaks from watching, reading, or listening to news stories and social media. It’s good to be informed but consider limiting news to just a couple times a day and disconnecting from phones, TVs, and computer screens for a while.

- It can be important to do a self check-in before reading any news. “Do I have the emotional energy to handle a difficult headline if I see one?”

- Take care of your body.

- Take deep breaths, stretch, or meditate

- Try to eat healthy, well-balanced meals

- Exercise regularly

- Get plenty of sleep

- Avoid excessive alcohol, tobacco, and substance use

- Continue routine preventive measures (such as vaccinations, cancer screenings, etc.) as recommended by your health care provider

- Make time to unwind. Plan activities you enjoy.

- Purposefully connect with others. It is especially important to stay connected with your friends and family. Helping others cope through phone calls or video chats can help you and your loved ones feel less lonely or isolated. Connect with your community or faith-based organizations.

- Use the techniques described in the WHO stress management guide.[37]

Strategies for Self-Care

By becoming self-aware regarding signs of stress, you can implement self-care strategies to prevent compassion fatigue and burnout. Use the following “A’s” to assist in building resilience, connection, and compassion[38]:

- Attention: Become aware of your physical, psychological, social, and spiritual health. What are you grateful for? What are your areas of improvement? This protects you from drifting through life on autopilot.

- Acknowledgement: Honestly look at all you have witnessed as a health care professional. What insight have you experienced? Acknowledging the pain of loss you have witnessed protects you from invalidating the experiences.

- Affection: Choose to look at yourself with kindness and warmth. Affection and self-compassion prevent you from becoming bitter and “being too hard” on yourself.

- Acceptance: Choose to be at peace and welcome all aspects of yourself. By accepting both your talents and imperfections, you can protect yourself from impatience, victim mentality, and blame.

- American Psychological Association. (n.d.). Stressor. APA Dictionary of Psychology. https://dictionary.apa.org ↵

- Betts, J. G., Young, K. A., Wise, J. A., Johnson, E., Poe, B., Kruse, D. H., Korol, O., Johnson, J. E., Womble, M., & DeSaix, P. (2022). Anatomy and physiology 2e. OpenStax. https://openstax.org/books/anatomy-and-physiology-2e/pages/1-introduction ↵

- Shaw, W., Labott-Smith, S., Burg, M. M., Hostinar, C., Alen, N., van Tilburg, M. A. L., Berntson, G. G., Tovian, S. M., & Spirito, M. (2018). Stress effects on the body. American Psychological Association. https://www.apa.org/topics/stress/body ↵

- Kelly, J. F., & Coons, H. L. (2019). Stress won’t go away? Maybe you are suffering from chronic stress. American Psychological Association. https://www.apa.org/topics/stress/chronic ↵

- Shaw, W., Labott-Smith, S., Burg, M. M., Hostinar, C., Alen, N., van Tilburg, M. A. L., Berntson, G. G., Tovian, S. M., & Spirito, M. (2018). Stress effects on the body. American Psychological Association. https://www.apa.org/topics/stress/body ↵

- Shaw, W., Labott-Smith, S., Burg, M. M., Hostinar, C., Alen, N., van Tilburg, M. A. L., Berntson, G. G., Tovian, S. M., & Spirito, M. (2018). Stress effects on the body. American Psychological Association. https://www.apa.org/topics/stress/body ↵

- Shaw, W., Labott-Smith, S., Burg, M. M., Hostinar, C., Alen, N., van Tilburg, M. A. L., Berntson, G. G., Tovian, S. M., & Spirito, M. (2018). Stress effects on the body. American Psychological Association. https://www.apa.org/topics/stress/body ↵

- Shaw, W., Labott-Smith, S., Burg, M. M., Hostinar, C., Alen, N., van Tilburg, M. A. L., Berntson, G. G., Tovian, S. M., & Spirito, M. (2018). Stress effects on the body. American Psychological Association. https://www.apa.org/topics/stress/body ↵

- Shaw, W., Labott-Smith, S., Burg, M. M., Hostinar, C., Alen, N., van Tilburg, M. A. L., Berntson, G. G., Tovian, S. M., & Spirito, M. (2018). Stress effects on the body. American Psychological Association. https://www.apa.org/topics/stress/body ↵

- Shaw, W., Labott-Smith, S., Burg, M. M., Hostinar, C., Alen, N., van Tilburg, M. A. L., Berntson, G. G., Tovian, S. M., & Spirito, M. (2018). Stress effects on the body. American Psychological Association. https://www.apa.org/topics/stress/body ↵

- Shaw, W., Labott-Smith, S., Burg, M. M., Hostinar, C., Alen, N., van Tilburg, M. A. L., Berntson, G. G., Tovian, S. M., & Spirito, M. (2018). Stress effects on the body. American Psychological Association. https://www.apa.org/topics/stress/body ↵

- Amnie, A. G. (2018). Emerging themes in coping with lifetime stress and implication for stress management education. SAGE Open Medicine, 6. https://doi.org/10.1177%2F2050312118782545 ↵

- Amnie, A. G. (2018). Emerging themes in coping with lifetime stress and implication for stress management education. SAGE Open Medicine, 6. https://doi.org/10.1177%2F2050312118782545 ↵

- Shaw, W., Labott-Smith, S., Burg, M. M., Hostinar, C., Alen, N., van Tilburg, M. A. L., Berntson, G. G., Tovian, S. M., & Spirito, M. (2018). Stress effects on the body. American Psychological Association. https://www.apa.org/topics/stress/body ↵

- Shaw, W., Labott-Smith, S., Burg, M. M., Hostinar, C., Alen, N., van Tilburg, M. A. L., Berntson, G. G., Tovian, S. M., & Spirito, M. (2018). Stress effects on the body. American Psychological Association. https://www.apa.org/topics/stress/body ↵

- Kelly, J. F., & Coons, H. L. (2019). Stress won’t go away? Maybe you are suffering from chronic stress. American Psychological Association. https://www.apa.org/topics/stress/chronic ↵

- Kelly, J. F., & Coons, H. L. (2019). Stress won’t go away? Maybe you are suffering from chronic stress. American Psychological Association. https://www.apa.org/topics/stress/chronic ↵

- Kelly, J. F., & Coons, H. L. (2019). Stress won’t go away? Maybe you are suffering from chronic stress. American Psychological Association. https://www.apa.org/topics/stress/chronic ↵

- The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. (2025). Nutrition and stress. https://campushealth.unc.edu/health_topic/nutrition-and-stress/ ↵

- Kelly, J. F., & Coons, H. L. (2019). Stress won’t go away? Maybe you are suffering from chronic stress. American Psychological Association. https://www.apa.org/topics/stress/chronic ↵

- Kelly, J. F., & Coons, H. L. (2019). Stress won’t go away? Maybe you are suffering from chronic stress. American Psychological Association. https://www.apa.org/topics/stress/chronic ↵

- Kelly, J. F., & Coons, H. L. (2019). Stress won’t go away? Maybe you are suffering from chronic stress. American Psychological Association. https://www.apa.org/topics/stress/chronic ↵

- Kandola, A. (2018). What are the health effects of chronic stress? MedicalNewsToday. https://www.medicalnewstoday.com/articles/323324#treatment ↵

- World Health Organization. (2020). Doing what matters in times of stress: An illustrated guide. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240003927 ↵

- World Health Organization. (2020). Doing what matters in times of stress: An illustrated guide. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240003927 ↵

- World Health Organization. (2020). Doing what matters in times of stress: An illustrated guide. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240003927 ↵

- World Health Organization. (2020). Doing what matters in times of stress: An illustrated guide. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240003927 ↵

- World Health Organization. (2020). Doing what matters in times of stress: An illustrated guide. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240003927 ↵

- World Health Organization. (2020). Doing what matters in times of stress: An illustrated guide. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240003927 ↵

- Fryburg, D. A. (2021). Kindness as a stress reduction-health promotion intervention: A review of the psychobiology of caring. American Journal of Lifestyle Medicine, 16(1), 89-100. doi: 10.1177/1559827620988268. ↵

- World Health Organization. (2020). Doing what matters in times of stress: An illustrated guide. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240003927 ↵

- World Health Organization. (2020). Doing what matters in times of stress: An illustrated guide. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240003927 ↵

- World Health Organization (WHO). (2020, November 4). Doing what matters in times of stress: An illustrated guide [Video]. YouTube. Licensed in the Public Domain. https://youtu.be/E3Cts45FNrk ↵

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2021). Healthcare personnel and first responders: How to cope with stress and build resilience during the COVID-19 pandemic. https://stacks.cdc.gov/view/cdc/95184 ↵

- “89118597-2933268333403014-548082632068431872-n.jpg” by unknown author for World Health Organization (WHO) is licensed in the Public Domain. Access for free at https://www.who.int/campaigns/connecting-the-world-to-combat-coronavirus/healthyathome/healthyathome---mental-health?gclid=Cj0KCQiA0MD_BRCTARIsADXoopa7YZldaIqCtKlGrxDV8YcUBtpVSD2HaOtT9NsdT8ajyCXbnPot-bsaAvlQEALw_wcB ↵

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2021). Healthcare personnel and first responders: How to cope with stress and build resilience during the COVID-19 pandemic. https://stacks.cdc.gov/view/cdc/95184 ↵

- World Health Organization. (2020). Doing what matters in times of stress: An illustrated guide. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240003927 ↵

- Lowey, S. E. (2015). Nursing care at the end of life. Open SUNY Textbooks. https://ecampusontario.pressbooks.pub/nursingcare/ ↵

Any internal or external event, force, or condition that results in physical or emotional stress.

The body’s physiological response to a real or perceived stressor.

Traumatic circumstances experienced during childhood such as abuse, neglect, or growing up in a household with violence, mental illness, substance use, incarceration, or divorce.