15.5 Intimate Partner Violence

Intimate partner violence (IPV), sexual assault, and rape are crimes with long-lasting effects on victims and are a great cost to society. These crimes happen to both women and men and are often associated with substance use. A recent national survey found that 22 percent of women and 14 percent of men reported experiencing severe physical violence from an intimate partner in their lifetimes.[1] IPV is a significant public health issue that has many individual and societal costs. About 35% of female IPV survivors and more than 11% of male IPV survivors experience some form of physical injury related to IPV, and some deaths occur. About one in five homicide victims is killed by an intimate partner, and over half of female homicide victims in the US are killed by a current or former male intimate partner.[2] See Figure 15.8[3] for a CDC infographic related to IPV.

Intimate partner violence (IPV) is abuse or aggression that occurs in a romantic relationship. “Intimate partner” refers to both current and former spouses and dating partners. IPV can vary in how often it happens and how severe it is. It can range from one episode of violence that could have lasting impact to chronic and severe episodes over multiple years. IPV can include any of the following types of behaviors[4]:

- Physical violence: When a person hurts or tries to hurt a partner by hitting, kicking, or using another type of physical force

- Sexual violence: Forcing or attempting to force a partner to take part in a sex act, sexual touching, or a nonphysical sexual event (e.g., sexting) when the partner does not or cannot consent

- Stalking: A pattern of repeated, unwanted attention and contact by a partner that causes fear or concern for one’s own safety or the safety of someone close to the victim

- Psychological aggression: The use of verbal and/or nonverbal communication with the intent to harm another partner mentally or emotionally and/or to exert control over another partner

View the following CDC YouTube video on intimate partner violence[5]: What is Intimate Partner Violence?

Teen Dating Violence

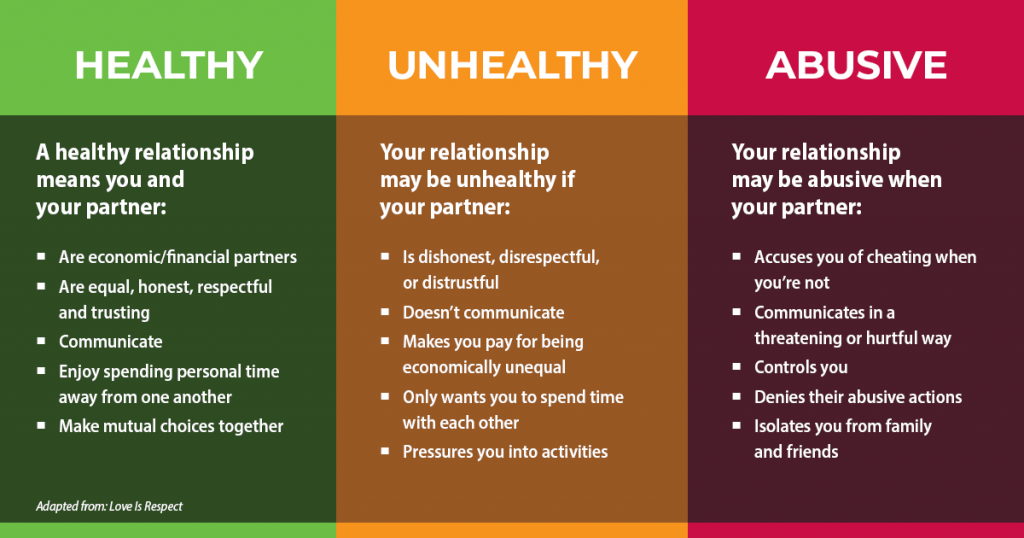

When IPV occurs during adolescence, it is referred to as teen dating violence (TDV). TDV affects millions of U.S. teens each year. The use of alcohol and drugs is a risk factor for non-consensual sexual contact among undergraduate and graduate students.[6] See Figure 15.9[7] for an infographic used to teach about healthy relationships.

Warning Signs of Intimate Partner Violence

These observations should heighten a nurse’s suspicion of IPV[8]:

- Inconsistent explanation of injuries.

- Delay in seeking treatment for injuries.

- Frequent emergency department or urgent care visits. (Abusers typically do not want their victims to form an ongoing care relationship with one clinician. They may feel the victim will be less likely to find an ally in an emergency department where care may be more fragmented.)

- Missed appointments. The client may not keep appointments because the abuser will not allow medical attention.

- Late initiation of prenatal care during pregnancy.

- Repeated abortions. Unplanned pregnancy may result from sexual assault and/or not being allowed to use birth control by the abuser.

- Medication nonadherence. Victims may not take medicines because the abuser has taken them away or not allowed the partner to fill prescriptions.

- Inappropriate affect. Victims may appear jumpy, fearful, or cry readily. They may avoid eye contact and seem evasive or hostile. Additionally, flat affect or dissociation may suggest post-traumatic stress disorder.

- Overly attentive or verbally abusive partner. The clinician should be suspicious if the partner answers questions for the client. If the partner refuses to leave the examination room, the nurse should find a way to get the partner to leave before questioning the client.

- Apparent social isolation.

- Reluctance to undress or have a genital, rectal, or oral examination or difficulty undergoing these or other examinations.

Assessment

The setting in which questioning occurs is important. The nurse must ensure that the client feels safe and comfortable. Individuals are more likely to disclose their experiences of IPV when the nurse uses the following strategies[9]:

- Provide privacy. Other people present in the room should be asked to leave for the interview and examination. Resistance of a partner to leave is a warning sign.

- Assure confidentiality (unless mandatory reporting is required).

- Use open-ended questioning and ask only a few questions.

- Ask about “being hurt” or “treated badly” and avoid phrases like “victim,” “abused,” or “battered.” Mirror the client’s word choices and use words like “hurt,” “frightened,” or “treated badly.”

- Do not disclose or discuss your concerns with the client’s partner.

- Do not ask why the client has not left their partner.

The physical examination can provide warning signs that abuse may be occurring. The presence and location of injuries are important. Any injury without a good explanation, particularly involving the head and neck, teeth, or genital area, should raise suspicion. Wounds on the forearms often occur when a victim is in a defensive position. Bruises of different ages may be present due to repeated abuse.

People experiencing abuse may deny the abuse for several reasons. They may not feel safe in disclosing information, especially if questions are not asked in a private environment or there is a fear of information not being kept confidential. They may not be emotionally ready to admit the reality of the situation, they may blame themselves, or they may feel like a failure if they admit to being abused. They may fear rejection, feel ashamed, believe that the abuse will not happen again, fear reprisal by the abuser, believe that they have no alternatives, or lack knowledge of resources that could help them. There may be language or cultural barriers between nurses and clients that interfere with communication or discomfort with using an interpreter to discuss sensitive issues.[10]

Routine screening is recommended for all clients on initial primary care visits, OB-GYN visits, emergency department visits, and on hospital admission.[11]

SAFE Survey

The Joint Commission recommends that hospitals use criteria to identify possible victims of abuse and neglect upon hospital entry and on an ongoing basis, educate staff about how to recognize signs of abuse, assist with referrals of possible victims, and report abuse in accordance with law and regulation.

Several IPV screening tools have been studied for use in emergency departments and clinics. SAFE is an example of a short survey tool that stands for the following assessments[12],[13]:

- S: Stress/Safety: Do you feel safe in your relationship?

- A: Afraid/Abused: Have you ever been in a relationship where you were threatened, hurt, or afraid?

- F: Friends/Family: Are your friends or family aware you have been hurt?

- E: Emergency Plan: Do you have a safe place to go and the resources you need in an emergency?

Read the following PDF for additional information about Minnesota Department of Health’s IPV screening tools: Family Home Visiting Intimate Partner Violence Screening & Referrals Toolkit.

Interventions and Safety Plans

Survivors of IPV are often afraid to leave their abusive partners because of the threats that have been made against them or their loved ones. The biggest threats for victims are strangulation (ten times more likely to be killed), the presence of a firearm (five times more likely), or if the abusive person is suicidal. It is not uncommon for an abusive person to threaten to kill themselves if they feel as if they’re losing control over their partner, and they pose a serious risk to their victim if they have attempted suicide in the past, talk about a specific plan, or have access to a gun. Domestic violence is the single biggest indicator of murder-suicides in the United States, and this has escalated to include survivors’ friends and family.[14]

Safety is a top priority when IPV is identified. Before the client leaves the office, referrals to local resources should be made with a personalized safety plan in place. The most dangerous time in a relationship occurs when the abused person decides to leave. Nearly 77 percent of domestic violence-related homicides occur upon separation, and there is a 75 percent increase of violence upon separation for at least two years.[15] As the abuser realizes they are losing power and control over their partner, they often escalate tactics to increase fear in the individual leaving the relationship in an effort to make the individual stay. A safety plan is a set of actions that can help lower the risk of being hurt by an abusive partner. It includes specific information and resources that will increase one’s safety at school, home, and other places visited regularly. View an infographic related to a safety plan in Figure 15.10.[16]

Resources for Survivors of IPV

Guide clients experiencing IPV to create a personalized online safety plan at the National Domestic Violence Hotline’s Create a Safety Plan web page.

If you need help or know someone who is experiencing IPV, visit the National Domestic Violence Hotline or call 1-800-799-7233. Online resources for developing a customized safety plan are available.

Read about teen dating and healthy relationships at the Love is Respect website.

Preventing IPV

There are many negative health outcomes associated with IPV, including chronic conditions affecting the heart, digestive, reproductive, musculoskeletal, and nervous systems. Survivors may experience mental health problems such as depression and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and are at higher risk for engaging in behaviors such as smoking, binge drinking, and risky sexual behaviors.[17]

Nurses and communities can promote healthy, respectful, and nonviolent relationships to help reduce the occurrence of IPV.[18] See Figure 15.11[19] for an infographic related to IPV prevention strategies from the CDC.

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), Office of the Surgeon General. (2016). Facing addiction in America: The surgeon general’s report on alcohol, drugs, and health. [PDF Report]. https://addiction.surgeongeneral.gov/sites/default/files/surgeon-generals-report.pdf ↵

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), Office of the Surgeon General. (2016). Facing addiction in America: The surgeon general’s report on alcohol, drugs, and health. [PDF Report]. https://addiction.surgeongeneral.gov/sites/default/files/surgeon-generals-report.pdf ↵

- “how-big-is-the-problem-ipv-large” by Centers for Disease Control and Prevention is in the Public Domain. Access for free at https://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/intimatepartnerviolence/fastfact.html ↵

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2024). About violence prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/intimatepartnerviolence/index.html ↵

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2019, May 15). What is intimate partner violence? [Video]. YouTube. All rights reserved. https://youtu.be/VuMCzU54334 ↵

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), Office of the Surgeon General. (2016). Facing addiction in America: The surgeon general’s report on alcohol, drugs, and health. [PDF Report]. https://addiction.surgeongeneral.gov/sites/default/files/surgeon-generals-report.pdf ↵

- “teen-dating-violence-relationship-range-chart-graphic.png” by unknown author for FairFax County Department of Family Services, Domestic and Violent Services is used under Fair Use. Access for free at https://www.fairfaxcounty.gov/familyservices/domestic-sexual-violence/teen-dating-violence ↵

- Weil, A. (2024). Intimate partner violence: Diagnosis and screening. UpToDate. www.uptodate.com ↵

- Weil, A. (2024). Intimate partner violence: Diagnosis and screening. UpToDate. www.uptodate.com ↵

- Weil, A. (2024). Intimate partner violence: Diagnosis and screening. UpToDate. www.uptodate.com ↵

- Weil, A. (2024). Intimate partner violence: Diagnosis and screening. UpToDate. www.uptodate.com ↵

- Weil, A. (2024). Intimate partner violence: Diagnosis and screening. UpToDate. www.uptodate.com ↵

- Rabin, R. F., Jennings, J. M., Campbell, J. C., & Bair-Merritt, M. H. (2009). Intimate partner violence screening tools. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 36(5), 439-445.e4. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2009.01.024 ↵

- National Domestic Violence Hotline. (n.d.). Plan for safety. https://www.thehotline.org/plan-for-safety/ ↵

- Battered Women’s Support Services. (2020). Eighteen months after leaving domestic violence is still the most dangerous time. https://www.bwss.org/eighteen-months-after-leaving-domestic-violence-is-still-the-most-dangerous-time/ ↵

- “vaw-covid-1.jpg” by unknown author for World Health Organization is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO. Access for free at https://www.who.int/multi-media/details/make-a-safety-plan-for-you-and-your-children ↵

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2024). About violence prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/intimatepartnerviolence/index.html ↵

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2024, April 9). About violence prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/intimatepartnerviolence/index.html ↵

- “how-can-we-stop-ipv.PNG” by National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, Division of Violence Prevention is in the Public Domain. Access for free at https://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/intimatepartnerviolence/fastfact.html ↵

Abuse or aggression that occurs in a romantic relationship.

Intimate partner violence (IPV) that occurs during adolescence.

A set of actions that can help lower the risk of being hurt by an abusive partner.