14.5 Neurobiology of Substance Use Disorders

Severe substance use disorders, also called addictions, were once considered a moral failing or character flaw but are now known to be chronic illnesses. Scientific evidence shows that addiction to substances is a chronic brain disease that has potential for relapse and recovery.[1]

All addictive substances have powerful effects on the brain. These effects account for the euphoric or intensely pleasurable feelings that people experience during their initial use of alcohol or other substances. These feelings motivate people to use those substances again and again, despite the risks for significant harm. As individuals continue to misuse alcohol or other substances, progressive changes, called neuroadaptations, occur in the structure and function of the brain. These neuroadaptations drive the transition from controlled, occasional substance use to chronic misuse that can be difficult to control and can endure long after an individual stops using the substances. These changes can lead to the need for increased amounts of substances to achieve the same effect, referred to as tolerance. They may produce continued, periodic cravings for the substance that can lead to relapse. More than 60 percent of people treated for a substance use disorder experience relapse within the first year after they are discharged from treatment, and a person can remain at increased risk of relapse for many years.[2]

For many people, initial substance use involves an element of impulsivity (i.e., acting without foresight or regard for the consequences). For example, an adolescent may impulsively take a first drink, smoke a cigarette, experiment with marijuana, or succumb to peer pressure and try a party drug like Ecstasy. If the experience is pleasurable, this feeling positively reinforces the substance use, making the person more likely to take the substance again. Another person may take a substance to relieve negative feelings such as stress, anxiety, or depression. In this case, the temporary relief the substance brings from the negative feelings reinforces substance use, increasing the likelihood that the person will use again.[3]

Many other environmental and social stimuli can reinforce a behavior. For example, peer approval positively reinforces substance use for some people. Likewise, if drinking or using drugs with others provides a feeling of relief from social isolation, substance use is reinforced.[4]

Eventually, in the absence of the substance, a person may experience negative emotions such as stress, anxiety, or depression or the individual may feel physically ill. This is called withdrawal, which often leads the person to use the substance again to relieve the withdrawal symptoms. As use becomes an ingrained behavior, impulsivity shifts to compulsivity, and the primary drivers of repeated substance use shift from positive reinforcement (feeling pleasure) to negative reinforcement (feeling relief) as the person seeks to stop the negative feelings and physical illness that accompany withdrawal. Eventually, the person begins taking the substance not to get “high,” but rather to escape the “low” feelings from withdrawal. Compulsive substance seeking is a key characteristic of addiction, as well as loss of control over use. Compulsivity helps to explain why many people with addiction experience relapses after abstinence.[5]

Three regions of the brain are the key components in the development and persistence of substance use disorders: the basal ganglia, the extended amygdala, and the prefrontal cortex:

- The basal ganglia controls the rewarding, pleasurable effects of substance use and is responsible for the formation of habitual substance taking. Two subregions of the basal ganglia are particularly important in substance use disorders:

- The nucleus accumbens, involved in motivation and the experience of reward.

- The dorsal striatum, involved in forming habits and other routine behaviors.

- The extended amygdala is involved in the stress response and the feelings of unease, anxiety, and irritability that typically accompany substance withdrawal.

- The prefrontal cortex is involved in executive function (e.g., the ability to organize thoughts and activities, prioritize tasks, manage time, and make decisions), including exerting control over substance use.

These changes in the brain persist long after substance use stops and are associated with a high incidence of relapse with substance use disorders.

Risk Factors

Many factors influence the development of substance use disorders, including developmental, environmental, social, and genetic factors, and co-occurring mental health disorders. Other conditions called protective factors protect people from developing a substance use disorder or addiction. Examples of protective factors include positive self-image, self-control, and social competence. The relative influence of these factors varies across individuals and the life span.

Whether an individual ever uses alcohol or another substance and whether that initial use progresses to a substance use disorder of any severity depends on a number of factors, including the following[6]:

- A person’s genetic makeup and biological factors

- The age when substance use begins

- Psychological factors related to a person’s unique history and personality

- Environmental factors, such as the availability of drugs, family and peer dynamics, financial resources, cultural norms, exposure to stress, and access to social support

Early Life Experiences

The experiences a person has early in childhood and in adolescence can set the stage for substance use and sometimes escalate to substance use disorder. Early life stressors (referred to as adverse childhood experiences) include physical, emotional, and sexual abuse; neglect; household instability (such as parental substance use and conflict, mental illness, or incarceration of household members); and poverty.[7]

Review information on adverse childhood experiences in the “Mental Health and Mental Illness” section of Chapter 1.

Adolescence is a critical vulnerable period for substance misuse and the development of substance use disorders because a characteristic of this developmental period is risk-taking and experimentation. For some young people, this includes trying alcohol, marijuana, or other drugs. Additionally, the brain undergoes significant changes during this life stage, making it particularly vulnerable to substance exposure. For example, the frontal cortex, a region in the front part of the brain that includes the prefrontal cortex, does not fully develop until the early to mid-20s. Research shows that heavy drinking and drug use during adolescence affects development of this critical area of the brain.[8]

Approximately 74 percent of 18- to 30-year-olds admitted to treatment programs began using substances at the age of 17 or younger. Individuals who start using substances during adolescence often experience more chronic and intensive use, and they are at greater risk of developing a substance use disorder compared with those who begin use at an older age. In other words, the earlier the exposure, the greater the risk.[9]

Genetic and Molecular Factors

Genetic factors are thought to account for 40 to 70 percent of individual differences in risk for addiction. Although multiple genes are likely involved in the development of addiction, only a few specific gene variants have been identified that either predispose to or protect against addiction. Some of these variants have been associated with the metabolism of alcohol and nicotine, while others involve receptors and other proteins associated with key neurotransmitters and molecules involved in all parts of the addiction cycle. Genes involved in strengthening the connections between neurons and in forming drug memories have also been associated with addiction risk. Like other chronic health conditions, substance use disorders are influenced by the complex interplay between a person’s genes and environment.[10]

Concurrent Mental Health Disorders

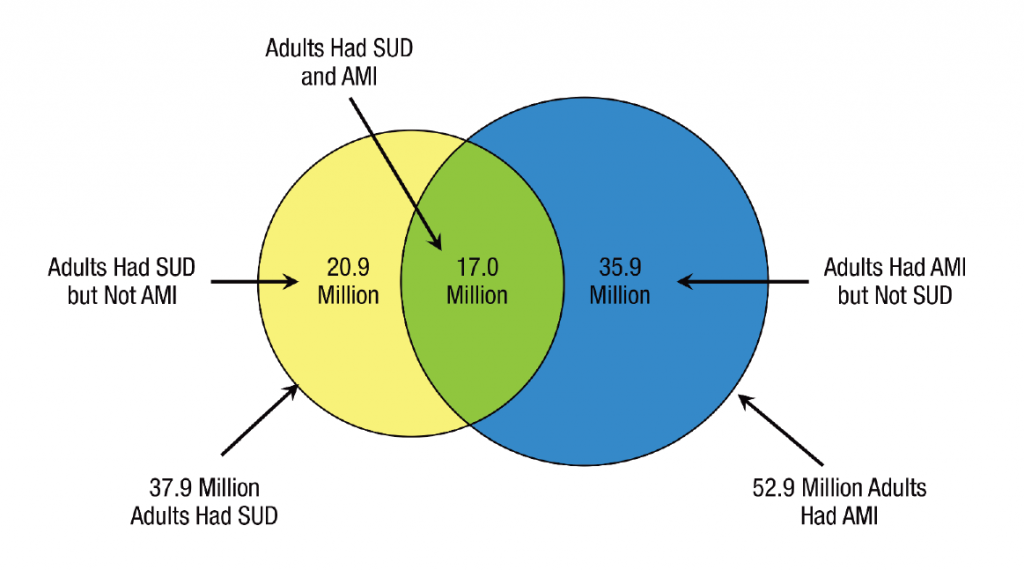

In 2020, 17 million adults (6.7%) had both a substance use disorder (SUD) and any mental health illness (AMI) as illustrated in Figure 14.7.[11] The relationship between SUDs and mental disorders is known to be bidirectional, meaning the presence of a mental health disorder may contribute to the development or exacerbation of an SUD, or an SUD may contribute to the development or exacerbation of a mental health disorder. The combined presence of SUDs and mental health disorders results in greater functional impairment; worse treatment outcomes; higher morbidity and mortality; increased treatment costs; and higher risk for homelessness, incarceration, and suicide.

The reasons why substance use disorders and mental health disorders often occur together are not clear, but there are three possible explanations. One reason may be because certain substances may temporarily mask the symptoms of mental health disorders (such as anxiety or depression). A second reason may be that certain substances trigger a mental health disorder that otherwise would not have developed. For example, research suggests that alcohol use increases risk for PTSD by altering the brain’s ability to recover from traumatic experiences. A third possible reason is that both substance use disorders and mental health disorders are caused by overlapping factors, such as particular genes, neurobiology, or exposure to traumatic or stressful life experiences.[12]

Mental health disorders and substance use disorders have overlapping symptoms, making diagnosis and treatment planning challenging. For example, people who use methamphetamine for a long period of time may experience paranoia, hallucinations, and delusions that can be mistaken for symptoms of schizophrenia.[13]

Gender

Some groups of people are more vulnerable to substance misuse and substance use disorders. For example, biological males tend to drink more than biological females and are at higher risk for alcohol use disorder. However, biological females who use cocaine, opioids, or alcohol may progress from initial use to a substance use disorder faster than males. Compared with biological males, biological females also exhibit greater withdrawal symptoms from some drugs such as nicotine and have higher levels of the stress hormone cortisol.[14]

Race and Ethnicity

Neurobiological factors contributing to differential rates of substance use disorders across racial and ethnic groups have been researched. A study using functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) found that African American smokers showed greater activation of the prefrontal cortex upon exposure to smoking-related cues than did White smokers, an effect that may partly contribute to the lower smoking-cessation success rates among African Americans.[15]

Alcohol research on racial and ethnic groups has shown that approximately 36 percent of East Asians carry a gene variant that alters the rate of alcohol metabolism, causing a buildup of acetaldehyde, a toxic by-product that produces symptoms such as flushing, nausea, and rapid heartbeat. Although these effects may protect some individuals of East Asian descent from alcohol use disorder, those who drink despite the effects are at increased risk for esophageal and head and neck cancers.[16]

Individual, Family, and Community Level Risk Factors

An individual’s risk factors for developing SUD include the following[17]:

- Early initiation of substance use: Engaging in alcohol or drug use at a young age

- Early and persistent problem behavior: Emotional distress, aggressiveness, and “difficult” temperaments in adolescents

- Rebelliousness: High tolerance for deviance and rebellious activities

- Favorable attitudes toward substance use: Positive feelings towards alcohol or drug use; low perception of risk

- Peer substance use: Friends and peers who engage in alcohol or drug use

- Genetic predictors: Genetic susceptibility to alcohol or drug use

- Academic failure beginning in late elementary school: Poor grades in school

- Lack of commitment to school: When a young person no longer considers the role of being a student as meaningful and rewarding or lacks investment or commitment to school

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, & Office of the Surgeon General. (2016). Facing addiction in America: The surgeon general's report on alcohol, drugs, and health. United States Department of Health and Human Services. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK424857/ ↵

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, & Office of the Surgeon General. (2016). Facing addiction in America: The surgeon general's report on alcohol, drugs, and health. United States Department of Health and Human Services. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK424857/ ↵

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, & Office of the Surgeon General. (2016). Facing addiction in America: The surgeon general's report on alcohol, drugs, and health. United States Department of Health and Human Services. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK424857/ ↵

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, & Office of the Surgeon General. (2016). Facing addiction in America: The surgeon general's report on alcohol, drugs, and health. United States Department of Health and Human Services. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK424857/ ↵

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, & Office of the Surgeon General. (2016). Facing addiction in America: The surgeon general's report on alcohol, drugs, and health. United States Department of Health and Human Services. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK424857/ ↵

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, & Office of the Surgeon General. (2016). Facing addiction in America: The surgeon general's report on alcohol, drugs, and health. United States Department of Health and Human Services. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK424857/ ↵

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, & Office of the Surgeon General. (2016). Facing addiction in America: The surgeon general's report on alcohol, drugs, and health. United States Department of Health and Human Services. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK424857/ ↵

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, & Office of the Surgeon General. (2016). Facing addiction in America: The surgeon general's report on alcohol, drugs, and health. United States Department of Health and Human Services. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK424857/ ↵

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, & Office of the Surgeon General. (2016). Facing addiction in America: The surgeon general's report on alcohol, drugs, and health. United States Department of Health and Human Services. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK424857/ ↵

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, & Office of the Surgeon General. (2016). Facing addiction in America: The surgeon general's report on alcohol, drugs, and health. United States Department of Health and Human Services. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK424857/ ↵

- Image is a derivative of “Past Year Substance Abuse Disorder (SUD) and Any Mental Illness (AMI): Among Adults Aged 18 or Older; 2020” table by Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. (2021). Key substance use and mental health indicators in the United States: Results from the 2020 National Survey on Drug Use and Health (HHS Publication No. PEP21-07-01-003, NSDUH Series H-56). Rockville, MD: Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Used under Fair Use. Retrieved from https://www.samhsa.gov/data/report/2020-nsduh-annual-national-report . ↵

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, & Office of the Surgeon General. (2016). Facing addiction in America: The surgeon general's report on alcohol, drugs, and health. United States Department of Health and Human Services. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK424857/ ↵

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, & Office of the Surgeon General. (2016). Facing addiction in America: The surgeon general's report on alcohol, drugs, and health. United States Department of Health and Human Services. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK424857/ ↵

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, & Office of the Surgeon General. (2016). Facing addiction in America: The surgeon general's report on alcohol, drugs, and health. United States Department of Health and Human Services. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK424857/ ↵

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, & Office of the Surgeon General. (2016). Facing addiction in America: The surgeon general's report on alcohol, drugs, and health. United States Department of Health and Human Services. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK424857/ ↵

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, & Office of the Surgeon General. (2016). Facing addiction in America: The surgeon general's report on alcohol, drugs, and health. United States Department of Health and Human Services. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK424857/ ↵

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, & Office of the Surgeon General. (2016). Facing addiction in America: The surgeon general's report on alcohol, drugs, and health. United States Department of Health and Human Services. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK424857/ ↵

Progressive changes in the structure or function of the brain due to misue of alcohol or other substances.