12.3 Psychological and Behavioral Therapy

Treatment of Childhood and Adolescent Mental and Neurodevelopmental Disorders

Mental, emotional, and behavioral disorders in childhood can cause long-term problems. Early treatment of a child’s mental health or behavioral problems can reduce problems at home, in school, and in forming friendships. It can also promote healthy development into adulthood.[1] Treatment for mental health disorders, neurodevelopmental disorders, and behavioral disorders include psychological therapy, parent training in behavioral management, and behavioral interventions for the classroom.

Psychological Therapies

Depending on the type and severity of the mental health disorder and the developmental age of the child, psychological therapy for children may be used in combination with prescribed medication. Psychological therapy helps a child manage their symptoms so that they can function well at home, in school, and in their community. For example, cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) works well for children with disruptive behavior disorders, depression, and anxiety.

Psychological therapy is conducted by trained mental health professionals for children and can be done individually or in groups. Psychological therapy with children can include talking, playing, or other activities to help the child express feelings and thoughts. Therapists may also observe parents and children together and make suggestions for different ways to respond to disruptive behaviors.[2] See Table 12.3 for a list of psychological therapies considered effective for common conditions in children and adolescents.[3]

Table 12.3. Psychological Therapies for Various Conditions in Children and Adolescents

| Therapies | Description | Indications |

|---|---|---|

| Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy (CBT)

|

|

|

| Dialectical Behavior Therapy (DBT) |

|

|

| Family Therapy |

|

|

| Group Therapy |

|

|

| Behavioral Management Training |

|

|

| Social Skills Training |

|

|

| Relaxation Training |

|

|

| Motivational Interviewing (MI) |

|

|

Behavioral Interventions

Behavioral interventions reward desired behaviors and reduce maladaptive coping behaviors. Most child and adolescent treatment settings used structured programs to motivate and reward age-appropriate behaviors. For example, the point or star system may be used where the child receives points or stars for desired behaviors, and then specific privileges are awarded based on the points or stars earned each day.[4]

Parent Training in Behavior Management

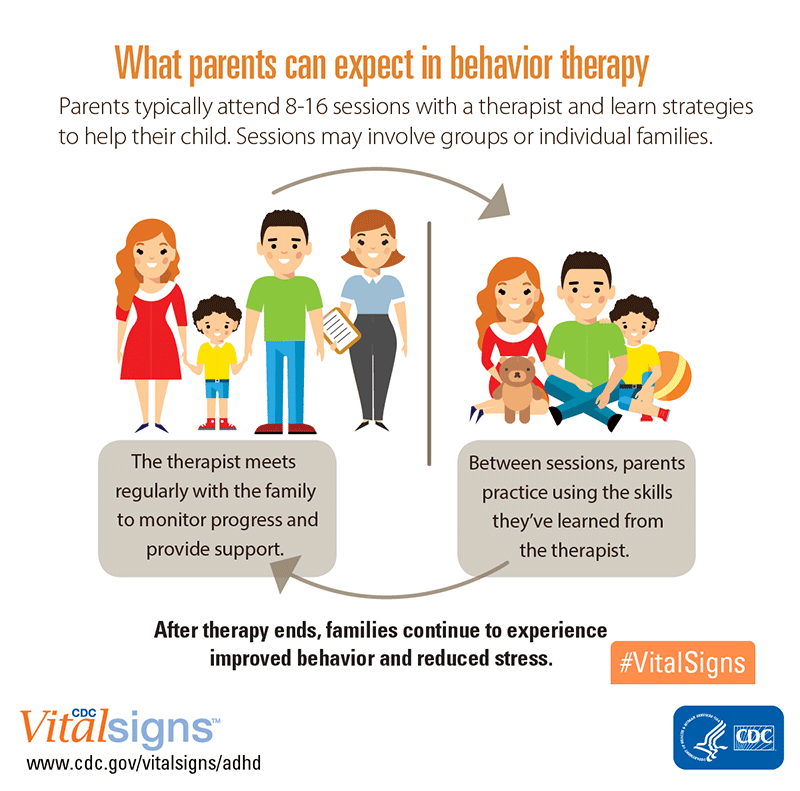

Parent training in behavior management includes teaching skills and strategies such as positive reinforcement, structure, and consistent discipline to manage their child’s behavior and help them succeed at school, at home, and in relationships.[5]

See Figure 12.6[6] for an illustration of parent training in behavioral management.

Behavioral Management Strategies

There are several evidence-based strategies that nurses can teach parents and caregivers to help manage behaviors of children and adolescents, such as time-out, special time, functional analysis of behavior, behavioral activation, sleep hygiene, and responding to bullying.[7]

Time-Out

“Time-out” is a strategy for shaping a child’s behavior through selective and temporary removal of the child’s access to desired attention, activities, or other reinforcements following a behavioral transgression. This strategy works for children who experience regular positive praise and attention from their parents or caregivers because they feel motivated to maintain that positive regard. The length of time should be about one minute for each year of age, but adjustments need to be made based on the child’s developmental level. For example, children with developmental delays should have shorter durations.[8]

Tips for caregivers implementing time-outs include the following[9]:

- Set consistent limits to avoid confusion.

- Focus on changing priority misbehaviors rather than everything at once.

- After setting a “time-out,” decline further verbal engagement until a “time-in.”

- Ensure time-outs occur immediately after misbehavior rather than being delayed.

- Follow through if using warnings (e.g., “I’m going to count to three…”).

- State when the time-out is over. Setting a timer can be helpful.

- When the time-out finishes, congratulate the child on regaining personal control and then look for the next positive behavior to praise.

- Give far more positive attention than negative attention.

Special Time

“Special time” is a strategy for a caregiver and a young child to establish the enjoyment of each other’s company. It is also referred to as “child-directed play” because it emphasizes that caregivers follow the child’s lead. Tips for caregivers implementing special time include the following[10]:

- Commit to setting aside a regular time for “special time.” Daily is best, but two to three times a week consistently also work.

- Select the time of day and label it as “our special time.”

- Choose a time short enough that it can happen reliably, usually 15-30 minutes. Ensure this time happens no matter how good or bad the day’s behaviors were.

- Allow the child to select the activity, which must be something you do not actively dislike or does not involve spending money or completing a chore.

- Follow the child’s lead during play, resisting the urge to tell them what to do.

- End of time; a timer may be helpful. Remind the child when the next special time will be.

- If the child refuses at first, explain you will just sit with them during the “special time.”

- Expect greater success if you set your own special times for yourself too.

Functional Analysis of Behavior

Functional analysis is a strategy for preventing a recurring problematic behavior by first identifying why a behavior keeps recurring and then devising a plan to prevent recurrences. For example, a parent reports their young child “throws temper tantrums every time we go to the store.” As the mental health professional helps the parent analyze the behavior, the parent realizes they have been giving the child candy to halt the tantrums, which actually functions to reward the behavior and encourages it to happen again. If the parent were to stop delivering this unintentional reward, the tantrums would theoretically decrease. Alternatively, the parent may focus on avoiding reexposing the child to a recognized trigger for the behavior, such as the candy aisle.[11]

Behavioral Activation

Behavioral activation is a strategy to encourage a young person to reengage with other people and do things they find pleasurable. When an individual is sad or anxious, they are less likely to engage in activities they enjoy, and this withdrawal can cause isolation and worsen the mood. The following is a list of tips to provide clients for succeeding with behavioral activation[12]:

- Identify activities that you (not others) find motivating or rewarding. Develop a list with a variety of options because repetitively doing the same thing can become boring.

- Refine the list to things that can be measured as completed rather than vague goals.

- Rank the activities in order of those most easily completed to those more difficult to complete.

- Start by selecting something easy to accomplish to get started and then work up the list in increasing level of difficulty.

- Let others know your plans and enlist their help in motivating you.

Sleep Hygiene

Insomnia is a common problem among children and adolescents. Most sleep problems can be resolved by changing habits and routines that affect sleep, commonly referred to as sleep hygiene. The following is a list of tips for caregivers for improving sleep hygiene[13]:

- Maintain consistent bedtimes and wake times every day of the week.

- Maintain a routine of pre-sleep activities (e.g., brush teeth, read a book).

- Avoid spending non-sleep time in or on one’s bed. (i.e., “beds are for sleep”).

- Ensure the bedroom is cool and quiet.

- Avoid highly stimulating activities just before bed (e.g., television, video games, social media, or exercise).

- Do not keep video games, televisions, computers, or phones in a child’s bedroom. Set a media curfew on technology use.

- Incorporate exercise into the day in order to aid with sleep.

- Avoid caffeine in the afternoons and evenings. Caffeine causes shallow sleep and frequent awakenings.

- Encourage children and adolescents to discuss any worries with the caregiver before bed rather than ruminating on it during sleep time.

- Ensure that children go to bed drowsy but still awake. Falling asleep in places other than a bed forms habits that are difficult to break.

- Use security objects with young children who need a transitional object with which to feel safe and secure when their caregiver is not present (e.g., a special blanket or toy).

- When checking on a young child at night, briefly reassure the child you are present, and they are OK.

- Avoid afternoon naps for all but very young children because they often interfere with nighttime sleep.

- If a child or adolescent is having sleep difficulties, keep a sleep diary to track sleep time, wake time, activities, and naps to identify patterns.

Responding to Bullying

Bullying occurs when a person seeks to harm, intimidate, or coerce someone perceived as vulnerable. If there is a sudden change in a child’s mood, behavior, sleep, body symptoms, academic performance, or social functioning, there is a possibility they are experiencing bullying. Cyberbullying is a significant public health concern with rates of cyberbullying estimates ranging from 14 to 57%.[14]

The following is a list of tips for assessing and responding to bullying[15]:

- Detect: Ask the child: “Sometimes kids get picked on or bullied. Have you ever seen this happen? Has it ever happened to you?” If the child responds “No” but bullying is suspected, suggest the caregivers speak with teachers and/or review the child’s social media accounts.

- Educate: Let children know that bullying is unacceptable and if they experience bullying, you will help them respond.

- Plan: Plan ways with the child to avoid bullying.

- Avoid places where bullying happens.

- Teach them to walk away when bullying occurs and tell a trusted adult who can be quickly accessed.

- Instruct the child to stay near adults where bullying occurs. Most bullying happens when adults are not around.

- If a child feels they can confront the bully, teach them to say in a calm, clear voice, “Bullying is not OK” to stop the behavior.

- If the child is comfortable with deflating the situation with humor, they can use humor to challenge the bullying.

- Encourage the child to ask their peers for support and ideas for dealing with the bully.

- Encourage caregivers to communicate the bullying to the school and other families and jointly devise solutions.

Read more information about addressing bullying at www.stopbullying.gov.

Behavioral Interventions for the Classroom

Behavioral interventions for the classroom help children and adolescents succeed academically. Behavioral classroom management is a teacher-led approach that encourages a student’s positive behaviors in the classroom through a reward system or a daily report card and discourages their negative behaviors. Organizational training teaches children and adolescents time management, planning skills, and ways to keep school materials organized to optimize student learning and reduce distractions.[16]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2025). Treating children’s mental health with therapy. https://www.cdc.gov/children-mental-health/treatment/?CDC_AAref_Val=https://www.cdc.gov/childrensmentalhealth/parent-behavior-therapy.html ↵

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2025). Treating children’s mental health with therapy. https://www.cdc.gov/children-mental-health/treatment/?CDC_AAref_Val=https://www.cdc.gov/childrensmentalhealth/parent-behavior-therapy.html ↵

- Hilt, R. J., & Nussbaum, A. M. (Eds.). (2016). DSM-5 pocket guide for child and adolescent mental health. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.books.9781615370511 ↵

- Halter, M. (2022). Varcarolis’ foundations of psychiatric-mental health nursing (9th ed.). Saunders. ↵

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2024). About attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). https://www.cdc.gov/adhd/about/?CDC_AAref_Val=https://www.cdc.gov/ncbddd/adhd/facts.html ↵

- “adhd-behavior-therapy-parents-800px.png” by National Center on Birth Defects and Developmental Disabilities is in the Public Domain. ↵

- Hilt, R. J., & Nussbaum, A. M. (Eds.). (2016). DSM-5 pocket guide for child and adolescent mental health. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.books.9781615370511 ↵

- Hilt, R. J., & Nussbaum, A. M. (Eds.). (2016). DSM-5 pocket guide for child and adolescent mental health. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.books.9781615370511 ↵

- Hilt, R. J., & Nussbaum, A. M. (Eds.). (2016). DSM-5 pocket guide for child and adolescent mental health. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.books.9781615370511 ↵

- Hilt, R. J., & Nussbaum, A. M. (Eds.). (2016). DSM-5 pocket guide for child and adolescent mental health. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.books.9781615370511 ↵

- Hilt, R. J., & Nussbaum, A. M. (Eds.). (2016). DSM-5 pocket guide for child and adolescent mental health. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.books.9781615370511 ↵

- Hilt, R. J., & Nussbaum, A. M. (Eds.). (2016). DSM-5 pocket guide for child and adolescent mental health. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.books.9781615370511 ↵

- Hilt, R. J., & Nussbaum, A. M. (Eds.). (2016). DSM-5 pocket guide for child and adolescent mental health. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.books.9781615370511 ↵

- Zhu, C., Huang, S., Evans, R., & Zhang, W. (2021). Cyberbullying among adolescents and children: A comprehensive review of the global situation, risk factors, and preventive measures. Frontiers in Public Health, 9. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2021.634909 ↵

- Hilt, R. J., & Nussbaum, A. M. (Eds.). (2016). DSM-5 pocket guide for child and adolescent mental health. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.books.9781615370511 ↵

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2024). About attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). https://www.cdc.gov/adhd/about/?CDC_AAref_Val=https://www.cdc.gov/ncbddd/adhd/facts.html ↵