12.2 Common Disorders and Disabilities in Children and Adolescents

Mental health disorders, including substance use disorders, are common among children and adolescents in the United States, with nearly 20 percent experiencing a mental health disorder in a given year.[1] The most commonly diagnosed mental health disorders in children aged 13-17 years are attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), anxiety problems, behavioral problems, and depression[2]:

- ADHD: 9.8% (approximately 6.0 million)

- Anxiety: 9.4% (approximately 5.8 million)

- Behavioral problems: 8.9% (approximately 5.5 million)

- Depression: 4.4% (approximately 2.7 million)

For adolescents, depression, substance use, and suicide are important concerns. The following statistics demonstrate these concerns in adolescents aged 12-17 years in 2018-2019, prior to the COVID-19 pandemic[3]:

- 36.7% had persistent feelings of sadness or hopelessness.

- 18.8% seriously considered attempting suicide; 8.9% attempted suicide.

- 15.1% had a major depressive episode.

- 4.1% had a substance use disorder.

- 1.6% had an alcohol use disorder.

After the COVID-19 pandemic, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) found an 8% increase in persistent feelings of sadness in youth.[4]

These common disorders, as well as developmental disabilities, tics and Tourette syndrome, substance misuse, and gender dysphoria will be discussed in this section. Autism, another type of neurodevelopmental disorder, is discussed in the “Autism Spectrum Disorder” section.

Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder

Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) is a neurodevelopmental disorder characterized by persistent patterns of inattention, hyperactivity, and impulsivity that interfere with functioning or development. It is one of the most common neurodevelopmental disorders of childhood. It is usually first diagnosed in childhood and often lasts into adulthood.[5] Young males are diagnosed more frequently than females. See Figure 12.1[6] for an image depicting a child struggling with symptoms of ADHD in school.

Signs and Symptoms

It is normal for children to exhibit challenging behaviors and have trouble focusing at certain times. However, children with ADHD often have more severe symptoms that cause difficulties at school, at home, or with friends[7]:

- Daydreaming

- Forgetting or losing things

- Squirming or fidgeting

- Talking too much

- Making careless mistakes or taking unnecessary risks

- Difficulty resisting temptation

- Difficulty getting along with others

Diagnosing a child with ADHD is a process requiring several steps by a mental health professional. There is no single test to diagnose ADHD, and many other problems such as anxiety, depression, sleep problems, and learning disorders can have similar symptoms as ADHD. The diagnostic process includes a medical exam; hearing and vision tests; and a checklist rating ADHD symptoms completed by parents, teachers, and the child.[8] These symptoms must be present in two or more settings (e.g. home, school) and cause significant impairment in social, academic, or occupational functioning.

Types of ADHD

There are three subcategories of ADHD, determined by which symptoms are most prominent in the individual[9]:

- Predominantly Inattentive Presentation: This involves difficulty organizing or completing tasks, focusing on details, or following instructions and conversations. The person is easily distracted or forgets details of daily routines. These behaviors are often misunderstood by others, who might label them as “laziness” or a lack of attention.

- Predominantly Hyperactive-Impulsive Presentation: This presentation includes constant fidgeting and excessive talking. Sitting still for extended periods, such as during meals or homework, is challenging. Young children may run, jump, or climb constantly. Restlessness and impulsivity are often observed in behaviors such as interrupting others, grabbing objects, speaking at inappropriate moments, or struggling to wait their turn or follow directions. Impulsive tendencies may also increase the likelihood of accidents or injuries compared to peers.

- Combined Presentation: This occurs when symptoms from both of the above categories are equally evident.

A person’s symptoms of ADHD can change over time, and their predominant presentation may change.

Causes of ADHD

The cause(s) and risk factors for ADHD are unknown, but current research shows that genetics play an important role. In addition to genetics, other possible risk factors include the following[10]:

- Brain injury

- Exposure to environmental risks (e.g., lead) during pregnancy or at a young age

- Alcohol and tobacco use during pregnancy

- Premature delivery

- Low birth weight

Research does not support popularly held views that ADHD is caused by eating too much sugar, watching too much television, or ineffective parenting. Many of these factors may worsen symptoms, especially in genetically predisposed people, but the evidence is not strong enough to conclude that they are the main causes of ADHD.[11] Recent studies have explored the role of diet in ADHD, yielding mixed findings. While research does not support the widely held belief that excessive sugar intake, excessive screen time, or ineffective parenting directly cause ADHD, certain dietary factors may influence symptom severity. Notably, a “few foods diet,” which eliminates potential allergens or hypersensitivity-triggering foods, has shown a strong correlation with symptom improvement in some children. This suggests that food allergies or intolerances may play a role in ADHD symptoms for a subset of individuals. However, further research is needed to establish causation.[12]

While the exact cause of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) is not fully understood, research suggests that several potential contributing factors may also play a role in its development. Genetic factors appear to be significant, as children with a family history of ADHD or other mental health conditions, such as anxiety or mood disorders, may have an increased risk. Environmental influences—including early exposure to trauma, chronic family conflict, or major life transitions like divorce or relocation—might also contribute to the expression of ADHD symptoms. Additionally, possible differences in brain chemistry and structure, particularly imbalances in neurotransmitters like dopamine and norepinephrine, and irregularities in brain circuits such as those involving the prefrontal cortex and amygdala have been studied. It is important to recognize that these are potential causes and that ADHD is likely the result of a complex interplay of genetic, environmental, and neurological factors rather than any single trigger.[13]

Treatments for ADHD

The treatment for childhood or adolescent ADHD is not curative; it primarily focuses on managing symptoms and improving functional outcomes. The Society for Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics emphasizes that treatment should focus on areas of functional impairment and include ongoing, scheduled monitoring throughout the client’s life span.

Management of ADHD typically involves a combination of pharmacologic and nonpharmacologic treatments tailored to the individual needs of the child or adolescent.

Behavioral Therapy and Psychotherapy

Behavioral interventions are a cornerstone of ADHD treatment, particularly for younger children. For preschool-aged children (4–5 years old), parent training in behavior management (PTBM) is recommended as the first line of treatment before considering medication, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. PTBM and behavioral classroom interventions are strongly recommended by the American Academy of Pediatrics and the American Academy of Family Physicians. These strategies are especially effective when combined with pharmacologic treatments. ADHD can significantly affect a child’s ability to pay attention, sit still, and maintain relationships with family members and peers due to disruptive behaviors. Psychotherapy can help improve behavior, self-control, and self-esteem.

In addition to behavioral interventions, cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) is beneficial, especially for adolescents, helping them develop coping strategies and enhance executive functioning. Educational interventions, such as Individualized Education Programs (IEPs) and 504 plans, provide tailored academic support to help children with ADHD succeed in school. Complementary and alternative medicine approaches—such as omega-3 fatty acid supplementation, dietary modifications (e.g., elimination of artificial food colorings), and regular physical activity—have shown some efficacy in symptom management. Finally, neurofeedback and cognitive training aim to improve attention and executive functioning through structured programs, though the evidence supporting these methods remains limited.[14],[15]

Read more in the “Psychological and Behavioral Therapy” section of this chapter.

Parent Education About Behavioral Management

Nurses can teach parents strategies for managing the behavior of their child or adolescent with ADHD[16]:

- Create a routine. Try to follow the same schedule every day, from wake-up time to bedtime.

- Get organized. Encourage your child to put school bags, clothing, and toys in the same place every day so that they will be less likely to lose them.

- Manage distractions. Limit screentime, limit noise, and provide a clean workspace when your child is doing homework. Some children with ADHD learn better if they are moving or listening to background music.

- Limit choices. To help your child avoid feeling overwhelmed or overstimulated, offer only a few options, such as letting them choose between two outfits, meals, or toys.

- Be clear and specific when you talk with your child. Let your child know you are listening by describing what you heard them say. Use clear, brief directions when they need to do something.

- Help your child plan. Break down complicated tasks into simpler, shorter steps. For long tasks, starting early and taking breaks may help limit stress.

- Use goals and praise or other rewards. Use a chart to list goals and track positive behaviors, and then let your child know they have done well by telling them or by rewarding their efforts in other ways. Be sure the goals are realistic because progress towards small steps is important to maintain a child’s self-esteem.

- Discipline effectively. Instead of scolding, yelling, or spanking, use effective directions, time-outs, or removal of privileges as consequences for inappropriate behavior.

- Create positive opportunities. Children with ADHD may find certain situations stressful. Discovering and encouraging what your child does well, whether it’s school, sports, art, music, or play, can help create positive experiences.

- Provide a healthy lifestyle. Nutritious food, lots of physical activity, and sufficient sleep are important for preventing ADHD symptoms from getting worse.

- Communicate regularly with teachers. Clear, regular communication between teachers and parents helps reinforce behavior management strategies at school and at home.

Parents can also be referred to ADHD support groups in the following box.

Support Groups for ADHD

CHADD: Information and resources on ADHD, including treatment options, local support groups for clients and parents, and online support communities

Attention Deficit Disorder Association (ADDA): Information and resources on ADD for adults living with the disorder, including support groups and workshops

Psychology Today Support Groups: Support groups near you for ADHD and other conditions

Pharmacotherapy

Medication may be prescribed to help children aged six and older manage their ADHD symptoms and help them control behaviors that cause difficulties with family, friends, and at school.[17]

Before medications are initiated, a comprehensive medical exam, including height, weight, blood pressure, heart rate, and cardiovascular history, should be performed. A pretreatment baseline should be established for common side effects such as appetite, sleep, headaches, and abdominal pain. Adolescent clients should also be assessed for substance use.[18]

The choice of medication by the prescriber depends on many factors, such as the following[19]:

- Duration of coverage (e.g., desired coverage for school day plus completion of homework)

- Desire to avoid medication administration at school

- Ability of the child to swallow pills or capsules

- Coexisting emotional or behavioral conditions

- History of substance abuse in the client or a household member (i.e., stimulants with less abuse potential are prescribed)

- Expense

- Preferences of the child and their caregivers

Stimulants

Stimulants such as methylphenidate (Ritalin), dextroamphetamine (Dexedrine), and dextroamphetamine-amphetamine (Adderall) are considered first-line treatment because of rapid onset of action and a long record of safety and efficacy. Stimulants are available in short-, intermediate-, and long-acting formulations. The exact mechanism of action of stimulants in ADHD is unknown, but they are known to affect the dopaminergic and noradrenergic systems, causing a release of catecholamines. Stimulants have been found to improve caregiver-child interactions, aggressive behavior, and academic productivity.[20]

Stimulants are controlled substances and require a Schedule II prescription.

Boxed Warning

CNS stimulants, including methylphenidate and amphetamine-like substances, have a high potential for abuse and dependence. The risk of abuse by the client or their family members should be assessed prior to prescribing stimulants, and signs of abuse and dependence should be evaluated while the client is receiving therapy.[21]

Side Effects

Stimulants may cause minor side effects that resolve when dosage levels are lowered, or a different stimulant is prescribed. The most common side effects include the following[22],[23]:

- Difficulty falling asleep or staying asleep

- Loss of appetite and weight loss

- Stomach pain

- Headache

Less common side effects include motor or verbal tics (sudden, repetitive movements or sounds) or personality changes (such as appearing “flat” or without emotion).[24] Sudden death, stroke, and myocardial infarction have been reported in adults with CNS-stimulant treatment at recommended doses. Sudden death has been reported in pediatric clients with structural cardiac abnormalities and other serious heart problems taking CNS stimulants at recommended doses. If paradoxical worsening of symptoms or other adverse reactions occur, the provider should be contacted, and the dosage reduced or discontinued. Stimulants are contraindicated in clients using a monoamine oxidase inhibitor (MAOI) or using an MAOI within the preceding 14 days.[25]

Nurses should be aware there is a possibility of diversion or misuse of stimulants by adolescents or their caregivers. Up to 29 percent of school- and college-aged students with stimulant prescriptions have been asked to give, sell, or trade their medication.[26]

Selective Norepinephrine Reuptake Inhibitors

Selective norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs) such as atomoxetine (Strattera) are an alternative to stimulants for clients who experience side effects with stimulants. They may also be helpful in treating concurrent depressive or anxiety disorders. SNRIs are not controlled substances, so they may be prescribed for adolescents (or their family members) with substance use disorders. The dosage depends on the child’s weight, and the duration of action is 10 to 12 hours. Atomoxetine has a Boxed Warning about increased risk of suicidal thinking in children and adolescents.[27]

Alpha-2 Adrenergic Agonists

Alpha-2 adrenergic agonists such as clonidine are typically used when children respond poorly to stimulants or SNRIs, have unacceptable side effects, or have significant coexisting conditions.

Client and Parent Education

There are several important client education topics to provide to clients and/or the parents of minor children[28]:

- Medication information: Discussing the purpose, potential side effects, and the importance of adherence to prescribed treatments.

- Controlled Substance Status/High Potential for Abuse and Dependence: Stimulants are a controlled substance by the FDA that can be abused and lead to dependence. Stimulants should be stored in a safe (preferably locked) place to prevent misuse and should not be shared with anyone. Unused or expired stimulants should be disposed of based on state law and regulations or returned to a medicine take-back program if it is available in the community.

- Cardiovascular Risks: Stimulants can increase blood pressure and pulse rate. Potential serious cardiovascular risks include sudden death, cardiomyopathy, myocardial infarction, stroke, and hypertension. Instruct clients to contact a health care provider immediately if they develop symptoms, such as exertional chest pain, dizziness, or passing out.

- Suppression of Growth: Stimulants may cause slowing of growth in children and weight loss.

- Psychiatric Risks: Stimulants can cause psychosis or manic symptoms, even in clients who have no prior history of these symptoms.

- Priapism: Painful or prolonged penile erections can occur; seek immediate medical attention.

- Alcohol: Alcohol should be avoided.

Nurses should reinforce with the client and their family members that the reason for the prescribed medication is to help with self-control and the ability to focus. Possible side effects should be reviewed, and clients and their family members should be reminded it may take one to three months to determine the best pharmacological treatment, dose, and frequency of medication administration. During this time, the child’s symptoms and adverse effects will be monitored weekly and the medication dose adjusted accordingly.[29]

ADHD Into Adulthood

ADHD lasts into adulthood for at least one third of children with ADHD. Treatments for adults can include medication, psychotherapy, or a combination of treatments.[30]

Anxiety

Some anxiety is a normal part of childhood and occurs at predictable stages of development. For example, from approximately age 8 months through the preschool years, healthy children may show anxiety when separated from their parents or caregivers. Young children also commonly have fears, such as fear of the dark, storms, animals, or strangers.[31] Anxiety is functional and normal human emotion when situational. Consider the fear of dangerous situations such as approaching a rattlesnake or standing on a steep cliff; at crucial times anxiety is important because it provides safety.

Anxiety is also motivational as it drives adolescents to accomplish goals such as passing a test by working hard and studying. Anxiety disorders are a group of mental health conditions characterized by excessive fear or worry that interferes with daily activities. Common types include egneralized anxiety disorder (GAD), social anxiety disorder, and panic disorder. Symptoms can be persistent and may manifest physically and emotionally. Anxiety disorders in children and adolescents are characterized by excessive fear, worry, or avoidance behaviors that are disproportionate to the actual threat and impair daily functioning.

Read more about “Adverse Childhood Experiences” in the “Trauma, Abuse, and Violence” chapter.

Symptoms of Anxiety Disorders in Children and Adolescents

Children with anxiety disorders are overly tense or fearful; some may seek lots of reassurance; and their worries may interfere with daily activities. Because anxious children may also be quiet, compliant, and eager to please, their feelings of anxiety can be easily missed. When a child does not outgrow the typical fears and anxieties in childhood or when there are so many fears and worries they interfere with school, home, or play activities, the child may be diagnosed with an anxiety disorder. Examples of symptoms related to different types of anxiety disorders in children and adolescents include the following[32]:

- Being very afraid when away from parents or caregivers (i.e., separation anxiety)

- Having extreme fear about a specific thing or situation, such as dogs, insects, or going to the doctor (i.e., phobias)

- Being very afraid of school and other places where there are people (i.e., social anxiety)

- Being very worried about the future and about bad things happening (i.e., general anxiety)

- Having repeated episodes of sudden, unexpected, intense fear associated with symptoms like fast heart rate, trouble breathing, dizziness, GI issues, or shakiness (i.e., panic disorder)

Anxiety can also cause irritability, anger, fatigue, headaches, stomachaches, or trouble sleeping.[33]

Treatment of Anxiety Disorders in Children and Adolescents

Early treatment of anxiety disorders in children can enhance friendships, social and academic potential, and self-esteem. Interprofessional treatments often include a combination of individual psychotherapy and behavioral therapy, family therapy, medications, and consultations with the child’s school.[34] The goal of treatment for anxiety disorders in children and adolescents is to reduce the severity of anxiety symptoms, improve functional impairment, and enhance overall quality of life. Overall, the treatment approach should be individualized, taking into account the severity of symptoms, the specific anxiety disorder, and the child’s developmental level. When a child is overly worried or anxious, a nurse’s initial assessment should determine if conditions in the child’s environment are causing this feeling. For example, is the anxiety resulting from being bullied or from adverse childhood experiences (ACEs)? If so, protective interventions should be put into place. If no realistic threat exists and the anxiety causes significant prolonged life dysfunction, then the child should be referred to a health provider to determine if an anxiety disorder exists.[35]

Read more about psychological and behavioral treatments for children and adolescents in the “Psychological and Behavioral Therapy” section.

Pharmacotherapy

Pharmacotherapy primarily involves the use of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), which have been shown to be effective and well-tolerated in children and adolescents with anxiety disorders. The American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry recommends SSRIs for clients aged 6 to 18 years with social anxiety, generalized anxiety, separation anxiety, or panic disorder. Common SSRIs used include fluoxetine, sertraline, and escitalopram. In cases of moderate to severe anxiety, a combination of CBT and SSRIs may be more effective than either treatment alone.[36],[37]

Client and Family Education

Effective client and family education is essential in the treatment of anxiety disorders in children and adolescents, as it empowers caregivers and young clients with the knowledge, skills, and support needed to manage symptoms, adhere to treatment plans, and promote long-term mental wellness. Key components of an effective education plan are as follows:

- Understanding Anxiety: Educating about the anxiety disorders and their symptoms, treatment options, and the importance of early intervention.

- Coping Strategies: Providing techniques for managing anxiety, including relaxation exercises and time management.

- Medication Guidance: Discussing the role of medications, potential side effects and benefits, and the importance of adherence to treatment plans.

- Support Resources: Connecting families with mental health resources, support groups, and counseling services for additional help. The role of CBT. Collaborative decision-making and providing resources such as written materials and reputable online information can support families in managing the condition.

Read additional information about anxiety disorders and associated treatments in the “Anxiety Disorders” chapter. Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) can develop in children or adolescents who have experienced a shocking, frightening, or dangerous event. It has similar symptoms to severe anxiety. Read more in the “Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder” section of the “Anxiety Disorders” chapter. There is also an association between obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) and children who have been exposed to trauma. Read more in the “Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder” section of the “Anxiety Disorders” chapter.

Depression

Every person feels sad occasionally. However, persistent sadness, hopelessness, withdrawal, or loss of interest in previously enjoyed activities may indicate depression. If these symptoms last for two or more weeks, a depressive disorder may be diagnosed. Depression, also known as major depressive disorder (MDD), is a mood disorder characterized by persistent feelings of sadness, hopelessness, and a loss of interest or pleasure in activities and various emotional and physical problems that interfere with daily functioning. It can affect how individuals think, feel, and handle daily activities and may lead to physical symptoms.[38]

Symptoms of Depressive Disorders in Children and Adolescents

Examples of behaviors observed in children and adolescents with a depressive disorder are as follows[39]:

- Feeling sad, hopeless, or irritable most of the time

- Not wanting to do or enjoy fun things

- Showing changes in eating patterns (e.g., eating a lot more or a lot less than usual)

- Showing changes in sleep patterns (e.g., sleeping a lot more or a lot less than normal)

- Showing changes in energy (e.g., being tired and sluggish or tense and restless most of the time)

- Difficulty paying attention

- Feeling worthless, useless, or guilty

- Engaging in self-injury or self-destructive behavior

- Having suicidal thoughts or making a plan for suicide

- Exhibiting physical complaints, such as frequent headaches or stomachaches

- Using alcohol or drugs as a way of trying to feel better

Depression might also cause a child to appear unmotivated or act out, causing others to incorrectly label the child as “lazy” or a “trouble-maker.”[40]

It is important to ask children and adolescents who are withdrawn or sad about self-harm risks. Adolescents may perceive a single disappointment (such as a relationship break-up) as so catastrophic they feel suicidal or begin to hurt themselves.[41]

Causes of Depression

The cause of depression is not always known. Depression can be hereditary but can also be situational or environmental. Some causes of depression are increased stress, death of a family member or close friend, social media, and bullying. Having other conditions such as attention problems, learning disorders, anxiety, or conduct disorders create a higher risk for depression.[42] Potential causes can be categorized as the following:

- Genetic Factors: A family history of depression or other mood disorders

- Environmental Stressors: Traumatic events, significant life changes (e.g., loss, divorce), or chronic stress

- Biological Factors: Neurochemical imbalances in the brain, hormonal changes, and physical health conditions

Treatment of Depressive Disorders in Children and Adolescents

First-line treatments for mild to moderate depression in children and adolescents typically include cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) and interpersonal therapy (IPT). For moderate to severe cases, a combination of psychotherapy and pharmacotherapy is often recommended.

- Psychotherapy: CBT is widely used to help young individuals identify and reframe negative thought patterns, build coping skills, and reduce depressive symptoms.

- Interpersonal Therapy (IPT): IPT focuses on enhancing interpersonal relationships and social functioning, which are often disrupted by depression.

- Lifestyle Modifications: Encouraging regular physical activity, balanced nutrition, and healthy sleep habits can play a supportive role in improving mood and overall well-being.

If depression is suspected, a nurse, school counselor, or other frontline professional can collaborate with the child’s parents or guardians to refer the child to a qualified mental health provider. A comprehensive assessment should guide treatment planning, which may include individual therapy, family-focused behavioral interventions, and coordination with the child’s school to support progress. In more severe cases, antidepressant medications may be prescribed in combination with therapy to achieve better outcomes.

Read more about behavioral treatments in the “Psychological and Behavioral Therapy” section.

Pharmacotherapy

Pharmacologic treatment for depression in children and adolescents is typically reserved for moderate to severe cases and should be guided by a thorough clinical evaluation. The only FDA-approved antidepressants for pediatric use are fluoxetine (Prozac) for children aged 8 and older and escitalopram (Lexapro) for those aged 12 and older. These medications, both selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), have demonstrated effectiveness but must be prescribed with caution due to the increased risk of suicidal thoughts and behaviors in young clients. Other SSRIs, such as sertraline and citalopram, have shown promising results in clinical studies but are not FDA-approved for this population. Close monitoring, regular follow-up appointments, and collaboration with the child’s caregivers are essential when initiating or adjusting medication therapy.[43]

Client and Family Education

Educating both the client and their family is a vital component of effectively managing depression in children and adolescents. A well-informed support system can help recognize early signs, encourage treatment adherence, and promote a more stable and nurturing environment for recovery.

- Understanding Depression: Families should be educated about what depression is, including its symptoms (such as persistent sadness, irritability, fatigue, changes in appetite or sleep, and loss of interest in activities), how it impacts daily functioning, and its potential effects on academic performance, social relationships, and self-esteem. Education should also include how to recognize warning signs of worsening depression or suicidal ideation, such as increased withdrawal, talk of hopelessness, or sudden behavioral changes. Emphasizing the importance of a supportive home environment and regular follow-up appointments helps ensure continuity of care and early intervention when needed.

- Coping Strategies: Teaching children and their families healthy coping mechanisms such as mindfulness, deep breathing, journaling, physical activity, and structured routines can enhance emotional regulation and resilience. Parents and caregivers can model and encourage stress management strategies to support recovery.

- Medication Information: When pharmacotherapy is part of the treatment plan, it is essential to provide age-appropriate education about the purpose of the medication, potential side effects, and the critical importance of adhering to the prescribed regimen. Families should be encouraged to ask questions and to report any concerns or behavioral changes to the prescribing provider promptly.

- Support Resources: Families should be connected to community resources, such as school-based mental health programs, peer support groups, and educational websites, that provide trustworthy information. Counseling services for the child and family may also be beneficial. Providing written materials or recommending reputable online sources can help reinforce learning and offer continued support outside of clinical settings.[44]

Read more about depression and pharmacological treatments in the “Depressive Disorders” chapter.

Behavior Disorders

Children sometimes argue or act angry or defiant around adults. However, a behavior disorder is diagnosed when disruptive behaviors are uncommon for the child’s age, persist over time, or are severe. Two types of behavior disorders are oppositional defiant disorder and conduct disorder.[45]

Oppositional Defiant Disorder

All children are oppositional from time to time, particularly when they are feeling tired, hungry, stressed, or upset. They may argue, talk back, disobey, and defy parents, teachers, or other adults. Oppositional behavior is considered a normal part of development for children two to three years of age and early adolescents. However, uncooperative and hostile behavior becomes a serious concern when it is so frequent and consistent that it stands out when compared with other children of the same age or when it significantly affects the child’s social, family, and academic life. According to the DSM-5-TR, these behaviors must be present for at least six months to warrant clinical concern.[46]

When children act out persistently causing serious problems at home, in school, or with peers, they may be diagnosed with oppositional defiant disorder (ODD). Up to 16 percent of all school-age children and adolescents have ODD. ODD usually starts before 8 years of age. Individuals with ODD are more likely to act oppositional or defiant around people they know well, such as family members, a regular care provider, or a teacher.[47]

Examples of ODD behaviors include the following[48]:

- Often being angry or losing one’s temper

- Often arguing with adults or refusing to comply with adults’ rules or requests

- Often being resentful or spiteful

- Deliberately annoying others or becoming annoyed with others

- Often blaming other people for one’s own mistakes or misbehavior

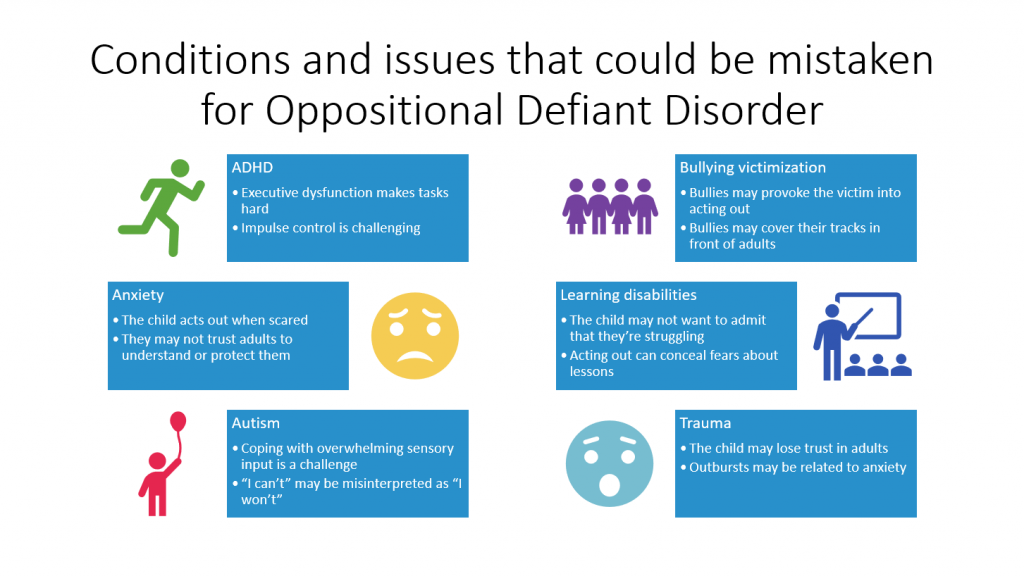

Many children with ODD may have coexisting conditions such as anxiety, post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), ADHD, autism, learning disabilities, or substance abuse. Some of these conditions may also be mistaken for ODD. See Figure 12.2[49] for an illustration of conditions that can be mistaken for ODD.

Causes of ODD

The etiology of oppositional defiant disorder (ODD) involves a complex interplay of genetic, environmental, and biological factors, with family dynamics playing a particularly significant role in the development and persistence of the disorder. According to the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, children with ODD typically direct their defiant and hostile behaviors toward authority figures, and these behaviors do not include the severe rule-breaking or antisocial acts seen in conduct disorder. Genetic influences, such as a family history of behavioral or mood disorders, may increase a child’s vulnerability. Environmental contributors—including inconsistent parenting practices and exposure to trauma, abuse, or neglect—can also play a critical role. Additionally, biological factors, such as differences in brain function and individual temperament, may predispose some children to exhibit oppositional and defiant behaviors more frequently or intensely than their peers.[50]

Treatment of ODD

Early intervention is critical to prevent the progression to more severe disorders such as conduct disorder and to mitigate long-term adverse outcomes. Treatment for ODD primarily involves behavioral therapy, focusing on improving parent-child interactions and implementing consistent discipline strategies.

Treatment of ODD includes the following[51]:

- Parent behavioral management training to help parents manage the child’s behavior

- Individual psychotherapy to develop more effective anger management skills

- Family psychotherapy to improve communication and mutual understanding

- Cognitive behavioral therapy and other psychotherapies to decrease negativity and enhance effective problem-solving

- Social skills training to increase flexibility and improve frustration tolerance with peers

Medications are not recommended as first-line treatment but may be used to address comorbid conditions, which can, in turn, alleviate ODD symptoms. They may be prescribed to control distressing symptoms of ODD, as well as symptoms related to coexisting conditions such as ADHD, anxiety, and mood disorders.[52]

Parent Education

Parents of children diagnosed with ODD need support and understanding. Nurses can teach parents to help their child with ODD in the following ways[53]:

- Understanding ODD: Educate families on the disorder, symptoms, and impact on functioning.

- Build on the positives. Give the child praise and positive reinforcement when they show flexibility or cooperation. Discipline will not work if there are no positive interactions.

- Take a time-out or break. If conflict with your child is progressively getting worse instead of better, take a time-out break. Demonstration of taking a break is also good modeling for the child. If the child decides to take a time-out to prevent overreacting, they should receive support for doing so.

- Prioritize your battles. Because the child with ODD has trouble avoiding power struggles, prioritize the things you want your child to do. For example, if you give your child a time-out in their room for misbehavior, don’t add time to the time-out for arguing. Instead, calmly say, “Your time will start when you go to your room.” Listen when they shout, but do not shout back.

- Set reasonable, age-appropriate limits and consequences. Set limits and establish consequences that can be enforced consistently. For example, if a child refuses to do homework, a reasonable consequence might be losing screen time for the evening.

- Maintain other interests. Manage your stress with healthy life choices such as exercise and relaxation. Maintain personal interests so that managing your child with ODD doesn’t take all your time and energy. Use respite care and other breaks as needed.

- Obtain support. Collaborate and obtain support from other adults working with your child (e.g., teachers and coaches).

Conduct Disorder

Conduct disorder (CD) is diagnosed when a child shows an ongoing pattern of aggression toward others with serious violations of rules and social norms at home, school, and with peers. These rule violations may involve breaking the law and result in arrest.[54] Adults with antisocial conduct disorder typically show symptoms of CD before age 15.[55]

Examples of CD behaviors are as follows[56]:

- Breaking serious rules, such as running away, staying out all night, or skipping school

- Being aggressive in a way that causes harm, such as bullying, fighting, or being cruel to animals

- Lying, stealing, or purposefully damaging other people’s property

Children who exhibit these serious behaviors should receive a comprehensive evaluation and treatment by a mental health professional. Some signs of behavior problems, such as not following rules in school, can be related to learning disorders that require additional assessment and interventions. Without treatment, many youngsters with conduct disorder are likely to have ongoing problems resulting in the inability to adapt to the demands of adulthood.[57]

Treatment for CD

Starting treatment early for CD is important. Research indicates the most effective treatment for younger children is behavior therapy training for parents—a therapist helps parents strengthen their relationship with the child and manage behavior effectively. For school-aged children and teens, a combination of behavior therapy training that includes the child, the family, and the school is most effective.[58] Read more about treatment in the “Psychological and Behavioral Therapy” section.

Developmental Disabilities

Developmental disabilities are a group of conditions with physical, learning, language, or behavioral impairments. These conditions begin during the developmental period, may impact day-to-day functioning, and usually last throughout a person’s lifetime.[59] Research indicates about 17% of children are diagnosed with a developmental disability such as blindness, hearing loss, learning disability, intellectual disability, seepch and language impairment, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), or autism spectrum disorder.[60]

Keep in mind that having a developmental disability does not mean the person is not healthy. Being healthy means staying well so one can lead a full, active life.[61]

Read more information about autism in the “Autism Spectrum Disorder” section and ADHD in the “Attention Disorder and Hyperactivity Disorder” subsection presented earlier in this section.

Causes and Risk Factors

Developmental disabilities begin anytime during the developmental period and usually last throughout a person’s lifetime. Most developmental disabilities begin before a baby is born, but some can occur after birth because of injury, infection, or other factors. Many developmental disabilities are thought to be caused by a complex mix of factors, including genetics, parental health and behaviors (such as maternal infections or substance use during pregnancy), complications during birth, infections the baby had very early in life, or exposure of the mother or child to high levels of environmental toxins, such as lead. However, there is no known cause for most developmental disabilities.[62]

Diagnosis of Developmental Disabilities

Developmental disabilities are diagnosed by developmental monitoring and developmental screening through a partnership between parents and health care professionals as a child’s growth and development are monitored.

Every child should receive routine screenings for developmental delays at their well-child visits. During a well-child visit, the provider performs developmental monitoring by observing for signs of developmental delays and talking with parents about any concerns they might have about their child’s growth and development. If any problems are noted during developmental monitoring, developmental screening is performed. Standardized tools used during developmental screening are formal questionnaires or checklists based on research that ask questions about a child’s development, including language, movement, thinking, behavior, and emotions. Developmental screening can be done by a doctor or nurse but may also be performed by other professionals in health care, early childhood education, community, or school settings to determine if a child is learning as expected or if there are delays.[63]

View an image of developmental milestones in Figure 12.3.[64]

View the CDC’s Developmental Milestones and Milestone Checklists PDF.

Types of Disorders

Based on developmental screenings, children may require further evaluation for language and speech disorders, learning disorders, and intellectual disabilities.

Language and Speech Disorders

Some children struggle with understanding language or speaking, and if they do not reach expected developmental milestones, it may be a sign of a language or speech disorder. Early childhood—especially the first three years—is a critical period when the brain rapidly develops these skills. A rich environment filled with sounds, sights, and regular communication best supports this development.[65]

Language development has many components. Children might have problems with one or more of the following[66]:

- Receptive Language: Difficulty understanding what others say due to not hearing the words (hearing loss) or not understanding the meaning of the words.

- Expressive Language: Difficulty communicating thoughts using language due to not knowing the words to use, not knowing how to put words together, or not being able to express the words.

Common indicators of language and speech disorders include[67]:

- Articulation Errors: Challenges forming specific words or sounds correctly

- Speech Fluency Issues: Problems with the smooth flow of words or sentences (e.g., stuttering)

- Auditory Processing Challenges: Struggles with interpreting the meaning of sounds

- Apraxia of Speech: Inability to sequence sounds and syllables correctly to form words

Children who struggle with language may become frustrated, which can lead to acting out, appearing helpless, or withdrawing from social interactions. Language or speech disorders may also occur alongside conditions such as ADHD, anxiety, or autism.[68]

If a child’s speech or language appears to be delayed, it is important to first determine whether a hearing loss is contributing to the problem. Hearing loss may be subtle—for instance, it might affect only one ear or certain sound frequencies. A doctor may refer the child to a speech-language pathologist, who will evaluate the child’s communication skills using spoken tests and conduct a hearing assessment. Based on this evaluation, the specialist can recommend activities to support language development at home, individual or group therapy, or further evaluation by an audiologist or developmental psychologist.[69]

For a detailed overview of what is considered typical for each age group, see the Hearing and Communicative Development Checklist. This checklist outlines key milestones from birth to five years of age and serves as a guide for identifying potential delays.

Learning Disorders

Many children may struggle with learning certain topics or skills in school from time to time. However, when children struggle with learning specific skills over time, it can be a sign of a learning disorder. Having a learning disorder means that a child has difficulty in one or more areas of learning, even when their overall intelligence or motivation are not affected.[70]

Some symptoms of learning disorders are as follows[71]:

- Difficulty telling right from left

- Reversing letters, words, or numbers after the first or second grade

- Difficulties recognizing patterns or sorting items by size or shape

- Difficulty understanding and following instructions or staying organized

- Difficulty remembering what was just said or what was just read

- Lacking coordination when moving around

- Difficulty doing tasks with the hands, like writing, cutting, or drawing

- Difficulty understanding the concept of time

Examples of learning disorders include the following[72]:

- Dyslexia: Difficulty with reading

- Dyscalculia: Difficulty with math

- Dysgraphia: Difficulty with writing

Children with learning disorders often experience frustration, which may lead to acting out, withdrawing, or exhibiting low self-esteem. These challenges can coexist with conditions such as ADHD or anxiety, further complicating academic success. Early detection and specialized instruction—such as individualized education programs (IEPs), targeted tutoring, or classroom accommodations—are key to helping these children overcome their difficulties and achieve their full potential. If difficulties persist for at least six months despite additional support, an evaluation by educational and health professionals is recommended.[73]

Intellectual Disabilities

Intellectual disability is defined in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM5) as a disorder with onset during the developmental period that includes both intellectual and adaptive functioning deficits in conceptual, social, and practical domains. The following criteria must be met for an individual to be diagnosed with an intellectual disability[74]:

- Deficits in intellectual functions, such as reasoning, problem-solving, planning, abstract thinking, judgment, academic learning, and learning from experience that is confirmed by both clinical assessment and individualized, standardized intelligence testing.

- Deficits in adaptive functioning that result in failure to meet developmental and sociocultural standards for personal independence and social responsibility. Without ongoing support, the adaptive deficits limit functioning in one or more activities of daily life, such as communication, social participation, and independent living, across multiple environments such as home, school, work, and the community.

- Onset of intellectual and adaptive deficits occurs during the developmental period.

Levels of intellectual disability vary greatly in children. Children with an intellectual disability might have a hard time communicating their needs, and an intellectual disability can cause them to develop more slowly than other children of the same age. Intellectual disability can be caused by a problem that starts any time before birth to when a child turns 18 years old. It can be caused by injury, disease, or other dysfunction in the brain. For many children, the cause of their intellectual disability is not known.[75]

The more severe the degree of intellectual disability, the earlier the signs can be noticed during developmental monitoring, such as the following[76]:

- Sitting up, crawling, or walking later than other children

- Talking later than other children or having trouble speaking

- Difficulty remembering things

- Difficulty understanding social rules

- Difficulty seeing the results of their actions

- Difficulty solving problems

The severity of intellectual disability (ID) varies widely and is classified based on the level of support an individual needs in daily life. Both the DSM-5-TR and the American Association on Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities (AAIDD) describe four levels of severity: mild, moderate, severe, and profound.[77]

Most individuals with ID fall into the mild to moderate range. These individuals typically develop conceptual, social, and daily living skills more slowly than their peers. However, with minimal to moderate support, they can learn practical life skills, communicate effectively, and often live semi-independently. Challenges may include difficulty with reading, managing money, or understanding time, but many can succeed in school and work with proper accommodations.

Severe intellectual disability is characterized by major developmental delays. Individuals in this category may understand some spoken language but have limited verbal communication skills. They often require significant support and supervision in their daily routines and may need help with hygiene, safety, and social interaction. A structured and supportive environment is essential for their well-being.

Profound ID is typically associated with congenital or genetic syndromes. These individuals require extensive support in nearly all areas of life. They have very limited communication abilities and often rely on gestures, sounds, or assistive technology to interact. Around-the-clock care is usually needed, and they benefit greatly from sensory-based therapies and consistent routines.

Signs of more severe intellectual disability often appear earlier in childhood. These may include delays in motor milestones (such as sitting, crawling, or walking), limited speech or language development, problems with memory, and difficulty understanding social rules or solving problems. Early identification and intervention are key to helping children with ID reach their full potential.[78]

Intellectual disabilities (ID) can arise from a complex interplay of genetic and environmental factors. Genetic conditions, such as Down syndrome and fragile X syndrome, are well-known contributors. Environmental influences—ranging from prenatal exposures to harmful substances, poor maternal nutrition, and birth complications—also play a significant role. Despite advances in research, the exact cause of an intellectual disability is not always identifiable, making comprehensive assessment essential for effective support planning.

Assessment of ID typically includes standardized tests to measure intellectual functioning, such as the Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children, as well as evaluations of adaptive behavior, like those conducted with the Vineland Adaptive Behavior Scales. These tools help professionals understand how well an individual manages everyday tasks in comparison to their peers. The results not only confirm a diagnosis but also inform the level and type of support a person may require across various settings.

Treatment for intellectual disabilities centers around three primary areas. First, addressing underlying causes is essential in cases where conditions like metabolic disorders (e.g., phenylketonuria) can be managed through specific interventions such as dietary adjustments. Second, treating comorbid medical or psychiatric conditions is critical. Many individuals with ID also experience issues like epilepsy, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), or anxiety, which may be managed through medications and psychosocial support. Third, enhancing adaptive skills is a major focus. Interventions may include early behavioral therapy, specialized education programs, and life skills training designed to promote independence and improve day-to-day functioning.

Treatment plans for individuals with ID are highly personalized and must adapt over time as needs change. While intellectual disability is typically a lifelong condition, early and targeted interventions have been shown to significantly enhance a person’s quality of life, communication abilities, and capacity for independence. Multidisciplinary support and family involvement are also key factors in achieving the best possible outcomes.

Children who are suspected to have an intellectual disability based on developmental screening are referred to a developmental pediatrician or other specialist for treatment.

Tics and Tourette Syndrome

Tourette syndrome (TS) and other tic disorders affect approximately 1% of school-aged children in the United States.[79] Tics are sudden twitches, movements, or sounds that people do repeatedly with the inability to stop their body from doing these actions. There are two types of tics: motor and vocal. Motor tics are movements of the body such as blinking, shrugging the shoulders, or jerking an arm. Vocal tics are sounds that a person makes with their voice such as grunting, humming, clearing the throat, or yelling out a word or phrase. Although the media often portray people with TS as involuntarily shouting out swear words (i.e., coprolalia) or constantly repeating the words of other people (i.e., echolalia), these symptoms are rare.[80]

The primary symptom of Tourette syndrome (TS) is tics that typically begin when a child is 5 to 10 years old. The first symptoms are often motor tics that occur in the head and neck area. Tics are often worse during times that are stressful or exciting and tend to improve when a person is calm or focused on an activity.[81]

In most cases, tics decrease during adolescence and early adulthood, and sometimes disappear entirely. However, many people with TS experience tics into adulthood and, in some cases, tics can become worse during adulthood.[82] Many individuals with TS also experience ADHD, obsessive-compulsive behaviors, anxiety, learning disabilities, behavioral issues, sleep disturbances, sensory processing issues, or social difficulties. These co-occurring conditions may have a greater impact on daily life than the tics themselves. In educational settings, tailored accommodations such as private study areas, modified testing environments, or individualized instruction can be very beneficial.

Tics are typically mild and do not require treatment, but it is essential to educate the individual and others about TS and provide appropriate support across all settings (e.g., school, work, and home). When tics become problematic or interfere with daily functioning, behavioral treatment or medication may be considered.[83]

View the following YouTube video of individuals with tics[84]: Tourette Syndrome is…

To read more about Tourette syndrome and tics, go to Tourette Association of America.

Substance Use Disorders

Children and adolescents may use alcohol and other substances for many reasons that may include maladaptive coping strategies or for other reasons. Alcohol is the most commonly used substance among young people in the United States. Data from several national surveys document frequent use of alcohol among young people. The 2019 Youth Risk Behavior Survey found these statistics among high school students during the past 30 days[85]:

- 22% Drank alcohol

- 16% Rode with a driver who has been drinking alcohol

- 5% Drove after drinking alcohol

- 17% Used electronic vapor products

- 17% Used marijuana

- 4% Smoked cigarettes

Binge drinking is defined as a pattern of alcohol consumption that brings the blood alcohol concentration level to 0.08% or more within about two hours. This pattern of drinking usually corresponds to five or more drinks on a single occasion for males or four or more drinks on a single occasion for females within about two hours.

Youth who binge drink alcohol are more likely to experience these issues[86]:

- School problems, such as higher rates of absences or lower grades

- Social problems, such as fighting or lack of participation in youth activities

- Legal problems, such as arrest for driving or physically hurting someone while drunk

- Physical problems, such as hangovers or illnesses

- Unwanted, unplanned, and unprotected sexual activity

- Disruption of normal growth or sexual development

- Physical and sexual violence

- Increased risk of suicide and homicide

- Alcohol-related motor vehicle crashes and other unintentional injuries, such as burns, falls, or drowning

- Memory problems

- Misuse of other substances

- Changes in brain development that may have lifelong effects

- Alcohol poisoning

Substance use disorders occur when the recurrent use of alcohol and/or drugs causes clinically significant impairment, including health problems, disability, and failure to meet major responsibilities at work, school, or home. The 2019 National Survey on Drug Use and Health reports that approximately 20.3 million people aged 12 or older had a substance use disorder in the past year.[87]

The Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) has developed a national campaign called “Talk. They Hear You” to help parents and caregivers start talking with their children early about the dangers of alcohol and other drugs.[88] See Figure 12.4[89] for an example of a public service announcement from the “Talk. They Hear You” campaign.

The vulnerability to substance use disorders is shaped by a complex interplay of factors that include genetics, early experiences, environmental influences, mental health, and family relationships. A family history of substance use can increase risk due to inherited traits and learned behaviors. Initiating substance use at a young age also raises the likelihood of developing a disorder, as early exposure can interfere with brain development and decision-making. Easy access to drugs or alcohol, along with widespread advertising, can lower barriers and increase temptation, especially in communities where substance use is normalized. Mental health challenges, such as anxiety or depression, often contribute to the risk as individuals may use substances to cope with emotional distress. Additionally, family environments characterized by low parental supervision, frequent conflict, or histories of abuse and neglect can further heighten vulnerability by reducing protective supports and increasing emotional instability.

Read more information in the “Substance Use Disorders” chapter.

Gender Dysphoria

Distinctions between gender, sexual orientation, and sexual behavior are a critical concept in adolescent health and are greatly influenced by one’s culture. Sex is assigned at birth based on the medical assessment of genitalia. Anatomical characteristics and chromosomes determine whether a person is biologically male or female. Gender identity, gender roles, and gender expression are psychological and cultural constructs referring to various aspects of maleness, femaleness, or other nonbinary designation.[90]

Gender identity is an individual’s innate sense of being male, female, androgynous (i.e., of indeterminate sex), nonbinary (i.e., a blend of both genders or don’t identify with either gender), or a preference to reject gender designation. An individual’s gender identity is generally established during early childhood but may evolve across their life span. Gender roles are social constructs based on masculinity and femininity that embody one’s culture’s expectations, attitudes, behaviors, and personality traits based on one’s biological sex. Gender expression refers to how an individual presents one’s gender to the outside world, but it does not necessarily correlate with their gender identity.[91]

An individual’s gender identity is influenced during early childhood by one’s parents and immediate family members defining how a person expresses themselves as members of their gender. As children become adolescents, their influences broaden with peer, media, and community norms of gender and sexuality impacting their individual value systems.[92]

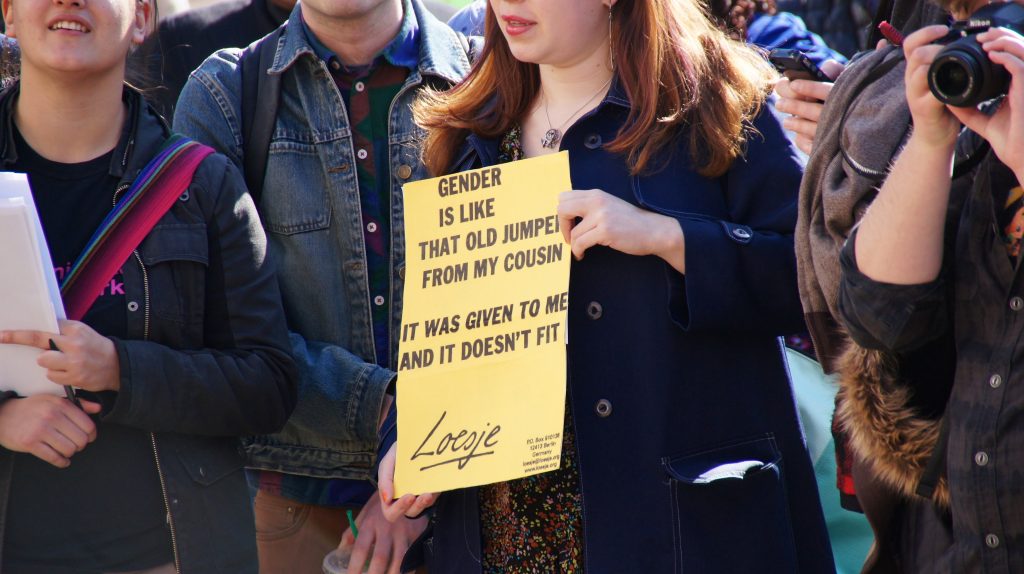

When a person’s biological sex differs from their gender identity, they experience feelings of unease about their incongruent maleness or femaleness referred to as gender dysphoria. For example, a biologic male with an innate sense of being female may describe themself as “a woman trapped in a man’s body.”[93] People who are transgender have a gender identity or gender expression that differs from the sex they were assigned at birth. See Figure 12.5[94] for an image of a person displaying a sign at a rally for transgender equality.

According to the DSM-5-TR, at least six of the following symptoms must be exhibited for at least six months and associated with distress or impaired functioning in order for a child to be diagnosed with gender dysphoria[95]:

- A strong desire to be of the other gender or an insistence they are another gender

- A strong preference for dressing in clothing stereotypical of the other gender

- A strong preference for playing with toys, games, or activities stereotypical of the other gender

- A strong rejection of the toys, games, and activities stereotypical of their assigned gender

- A strong preference for cross-gender roles when playing

- A strong preference for playmates of the other gender

- A strong dislike of one’s sexual anatomy

- A strong desire to have the primary and/or secondary sex characteristics of the other gender

Only a small percentage of children who display gender dysphoria will continue to show these characteristics into adolescence or adulthood. Adolescents with gender dysphoria who dread the appearance of secondary sexual characteristics may seek hormones or surgery to alter their masculinity or femininity.[96]

Sexual orientation is different from gender identity and gender expression. Sexual orientation refers to an individual’s pattern of physical, emotional, and romantic arousal (including fantasies, activities, and behaviors) and the gender(s) of persons to whom an individual is physically or sexually attracted. An individual’s assessment of their sexual orientation is termed sexual identity. Formation of sexual identity may be fluid with experimentation with same-gender sexual contacts as part of adolescent development. Approximately 5 to 10 percent of teens identify as lesbian, gay, or bisexual.[97]

Adolescents and adults who are mature and healthy in their sexuality are able to do the following[98]:

- Take responsibility for one’s own behavior

- Practice effective decision-making

- Affirm that human development includes sexual development, which may or may not include reproduction or sexual experience

- Seek further information about sexuality and reproduction as needed and make informed choices about family options and relationships

- Interact with all genders in respectful and appropriate ways

- Affirm one’s own gender identity and sexual orientation and respect the gender identities and sexual orientations of others

- Appreciate one’s body and enjoy one’s sexuality throughout life, expressing one’s sexuality in ways that are congruent with one’s values

- Express love and intimacy in appropriate ways

- Develop and maintain meaningful relationships, avoiding exploitative or manipulative relationships

- Exhibit skills and communication that enhance personal relationships with family, peers, and romantic partners

Health risks and adverse outcomes can occur more readily among youth who are gender-diverse or from sexual minorities. Risks and adverse outcomes can include child abuse, bullying, sexual harassment, teen dating violence, unprotected sex with risks for sexually transmitted infections and pregnancy, mental health problems (depression, anxiety, suicide, and disordered eating and body image), and substance use.[99]

Nurses should ask all clients, including adolescents, about their gender preferences and provide support if the client indicates a need for help. By promoting sexuality as healthy, respectful, and meaningful in the global context of adolescent development, nurses can encourage a positive model of empowerment for youth exploring their gender and sexual identities.[100]

- Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. (2025). Research protocol: Implementation of recommended screening and counseling interventions to prevent mental health disorders in children and adolescents. https://effectivehealthcare.ahrq.gov/products/behavioral-health-screening/protocol ↵

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2025). Data and statistics on children’s mental health. https://www.cdc.gov/children-mental-health/data-research/?CDC_AAref_Val=https://www.cdc.gov/childrensmentalhealth/data.html ↵

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2025). Data and statistics on children’s mental health. https://www.cdc.gov/children-mental-health/data-research/?CDC_AAref_Val=https://www.cdc.gov/childrensmentalhealth/data.html ↵

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2022). New CDC data illuminate youth mental health threats during the COVID-19 pandemic [Press Release]. https://www.cdc.gov/media/releases/2022/p0331-youth-mental-health-covid-19.html ↵

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2024). About attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). https://www.cdc.gov/adhd/about/?CDC_AAref_Val=https://www.cdc.gov/ncbddd/adhd/facts.html ↵

- “sad-gad250898b_1920” by Patrick Audet at Pixabay.com is licensed under CC0 ↵

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2024). About attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). https://www.cdc.gov/adhd/about/?CDC_AAref_Val=https://www.cdc.gov/ncbddd/adhd/facts.html ↵

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2024). About attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). https://www.cdc.gov/adhd/about/?CDC_AAref_Val=https://www.cdc.gov/ncbddd/adhd/facts.html ↵

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2024). About attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). https://www.cdc.gov/adhd/about/?CDC_AAref_Val=https://www.cdc.gov/ncbddd/adhd/facts.html ↵

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2024). About attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). https://www.cdc.gov/adhd/about/?CDC_AAref_Val=https://www.cdc.gov/ncbddd/adhd/facts.html ↵

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2024). About attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). https://www.cdc.gov/adhd/about/?CDC_AAref_Val=https://www.cdc.gov/ncbddd/adhd/facts.html ↵

- Lange, K. W., Lange, K. M., Nakamura, Y., & Reissmann, A. (2023). Nutrition in the management of ADHD: A review of recent research. Current Nutrition Reports, 12(3), 383-394. doi: 10.1007/s13668-023-00487-8 ↵

- Kowalchuk, A., Gonzalez, S. J., & Zoorob, R. J. (2022). Anxiety disorders in children and adolescents. American Family Physician, 106(6), 657-664. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/36521463/ ↵

- Chan, E., Fogler, J. M., & Hammerness, P. G. (2016). Treatment of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in adolescents: A systematic review. JAMA, 315(18), 1997-2008. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.5453. ↵

- Catalá-López, F., Hutton, B., Núñez-Beltrán, A., Page, M. J., Ridao, M., Macías Saint-Gerons, D., Catalá, M. A., Tabarés-Seisdedos, R., & Moher, D. (2016). The pharmacological and non-pharmacological treatment of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder in children and adolescents: A systematic review with network meta-analyses of randomised trials. PLoS One, 12(7), e0180355. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0180355. ↵

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2024). About attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). https://www.cdc.gov/adhd/about/?CDC_AAref_Val=https://www.cdc.gov/ncbddd/adhd/facts.html ↵

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2024). About attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). https://www.cdc.gov/adhd/about/?CDC_AAref_Val=https://www.cdc.gov/ncbddd/adhd/facts.html ↵

- Krull, K. R. (2022). Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder in children and adolescents: Treatment with medications. UpToDate. www.uptodate.com ↵

- Krull, K. R. (2022). Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder in children and adolescents: Treatment with medications. UpToDate. www.uptodate.com ↵

- Krull, K. R. (2022). Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder in children and adolescents: Treatment with medications. UpToDate. www.uptodate.com ↵

- National Institutes of Health. (n.d.). Black box warning. U.S. National Library of Medicine. https://www.nlm.nih.gov/ ↵

- National Institute of Mental Health. (2016). Mental health medications. U.S. Department of Health & Human Services. https://www.nimh.nih.gov/health/topics/mental-health-medications ↵

- National Institutes of Health. (n.d.). Black box warning. U.S. National Library of Medicine. https://www.nlm.nih.gov/ ↵

- National Institute of Mental Health. (2016). Mental health medications. U.S. Department of Health & Human Services. https://www.nimh.nih.gov/health/topics/mental-health-medications ↵

- National Institutes of Health. (n.d.). Black box warning. U.S. National Library of Medicine. https://www.nlm.nih.gov/ ↵

- Krull, K. R. (2022). Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder in children and adolescents: Treatment with medications. UpToDate. www.uptodate.com ↵

- Krull, K. R. (2022). Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder in children and adolescents: Treatment with medications. UpToDate. www.uptodate.com ↵

- National Institutes of Health. (n.d.). Black box warning. U.S. National Library of Medicine. https://www.nlm.nih.gov/ ↵

- Krull, K. R. (2022). Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder in children and adolescents: Treatment with medications. UpToDate. www.uptodate.com ↵

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2024). About attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). https://www.cdc.gov/adhd/about/?CDC_AAref_Val=https://www.cdc.gov/ncbddd/adhd/facts.html ↵

- American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. (2017). Anxiety and children. https://www.aacap.org/AACAP/Families_and_Youth/Facts_for_Families/FFF-Guide/The-Anxious-Child-047.aspx ↵

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2024). About children's mental health. https://www.cdc.gov/children-mental-health/about/index.html ↵

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2024). About children's mental health. https://www.cdc.gov/children-mental-health/about/index.html ↵

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2024). About children's mental health. https://www.cdc.gov/children-mental-health/about/index.html ↵

- Hilt, R. J., & Nussbaum, A. M. (Eds.). (2016). DSM-5 pocket guide for child and adolescent mental health. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.books.9781615370511 ↵

- Connolly, S. D., Suarez, L., & Sylvester, C. (2011). Assessment and treatment of anxiety disorders in children and adolescents. Current Psychiatry Reports, 13(2), 99-110. doi: 10.1007/s11920-010-0173-z. ↵

- Nicotra, C. M., & Strawn, J. R. (2023). Advances in pharmacotherapy for pediatric anxiety disorders. Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Clinics of North America, 32(3), 573-587. doi: 10.1016/j.chc.2023.02.006. ↵

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2024). About children's mental health. https://www.cdc.gov/children-mental-health/about/index.html ↵

- American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. (2017). Anxiety and children. https://www.aacap.org/AACAP/Families_and_Youth/Facts_for_Families/FFF-Guide/The-Anxious-Child-047.aspx ↵

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2024). About children's mental health. https://www.cdc.gov/children-mental-health/about/index.html ↵

- Hilt, R. J., & Nussbaum, A. M. (Eds.). (2016). DSM-5 pocket guide for child and adolescent mental health. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.books.9781615370511 ↵

- American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. (2017). Anxiety and children. https://www.aacap.org/AACAP/Families_and_Youth/Facts_for_Families/FFF-Guide/The-Anxious-Child-047.aspx ↵

- National Institute of Mental Health. (n.d.). Child and adolescent mental health: Depression. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. https://www.nimh.nih.gov/health/topics/child-and-adolescent-mental-health ↵

- National Institute of Mental Health. (n.d.). Child and adolescent mental health: Depression. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. https://www.nimh.nih.gov/health/topics/child-and-adolescent-mental-health ↵

- American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. (2019). Oppositional defiant disorder. https://www.aacap.org/aacap/families_and_youth/facts_for_families/fff-guide/Children-With-Oppositional-Defiant-Disorder-072.aspx ↵

- American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. (2019). Oppositional defiant disorder. https://www.aacap.org/aacap/families_and_youth/facts_for_families/fff-guide/Children-With-Oppositional-Defiant-Disorder-072.aspx ↵

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2025). Behavior or conduct problems in children. https://www.cdc.gov/children-mental-health/about/about-behavior-or-conduct-problems-in-children.html ↵

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2025). Behavior or conduct problems in children. https://www.cdc.gov/children-mental-health/about/about-behavior-or-conduct-problems-in-children.html ↵

- “Instead_of_Oppositional_Defiant_Disorder_1_Wide.png” by MissLunaRose12 is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0 ↵

- Lin, X., He, T., Heath, M., Chi, P., & Hinshaw, S. (2022). A systematic review of multiple family factors associated with oppositional defiant disorder. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(17), 10866. doi: 10.3390/ijerph191710866. ↵

- American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. (2019). Oppositional defiant disorder. https://www.aacap.org/aacap/families_and_youth/facts_for_families/fff-guide/Children-With-Oppositional-Defiant-Disorder-072.aspx ↵

- American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. (2019). Oppositional defiant disorder. https://www.aacap.org/aacap/families_and_youth/facts_for_families/fff-guide/Children-With-Oppositional-Defiant-Disorder-072.aspx ↵

- American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. (2019). Oppositional defiant disorder. https://www.aacap.org/aacap/families_and_youth/facts_for_families/fff-guide/Children-With-Oppositional-Defiant-Disorder-072.aspx ↵

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2025). Behavior or conduct problems in children. https://www.cdc.gov/children-mental-health/about/about-behavior-or-conduct-problems-in-children.html ↵

- Mayo Clinic. (2019). Antisocial personality disorder. https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/antisocial-personality-disorder/symptoms-causes/syc-20353928#:~:text=Adults%20with%20antisocial%20personality%20disorder,Destruction%20of%20property ↵

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2025). Behavior or conduct problems in children. https://www.cdc.gov/children-mental-health/about/about-behavior-or-conduct-problems-in-children.html ↵

- American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. (2018). Conduct disorder. https://www.aacap.org/aacap/families_and_youth/facts_for_families/fff-guide/conduct-disorder-033.aspx ↵

- American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. (2018). Conduct disorder. https://www.aacap.org/aacap/families_and_youth/facts_for_families/fff-guide/conduct-disorder-033.aspx ↵

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2021). Increase in developmental disabilities among children in the United States. https://www.cdc.gov/ncbddd/developmentaldisabilities/features/increase-in-developmental-disabilities.html ↵

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2024). Developmental disabilities. https://www.cdc.gov/environmental-health-tracking/php/data-research/developmental-disabilities.html ↵

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2024). Developmental disabilities. https://www.cdc.gov/environmental-health-tracking/php/data-research/developmental-disabilities.html ↵

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2024). Developmental disabilities. https://www.cdc.gov/environmental-health-tracking/php/data-research/developmental-disabilities.html ↵

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2024). Developmental disabilities. https://www.cdc.gov/environmental-health-tracking/php/data-research/developmental-disabilities.html ↵

- “Vroom-Poster_14x8.5_FNL-508” by National Center on Birth Defects and Developmental Disabilities, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention is in the Public Domain. ↵

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2021). Language and speech disorders in children. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/products/databriefs/db205.htm ↵

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2021). Language and speech disorders in children. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/products/databriefs/db205.htm ↵

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2021). Language and speech disorders in children. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/products/databriefs/db205.htm ↵

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2021). Language and speech disorders in children. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/products/databriefs/db205.htm ↵