5.2 Basic Concepts

A nasogastric (NG) tube is a flexible plastic tube inserted through a nostril, down the posterior oropharynx, and into the stomach or the upper portion of the small intestine. It is typically used for decompression of the stomach for clients with an intestinal obstruction or ileus or for administration of nutrition or medication to clients who are at risk for aspiration or unable to tolerate oral intake. Depending on the intended purpose of the tube, there are different types of NG tubes designed specifically for its use.[1]

Anatomy and Physiology

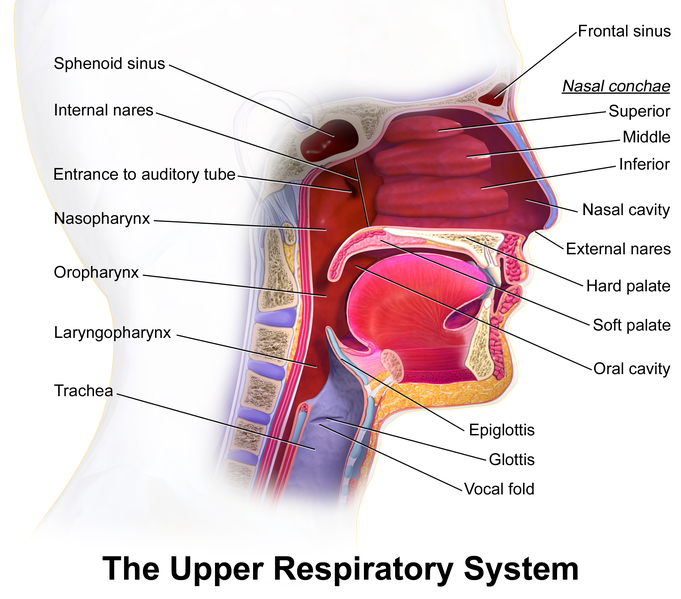

The nurse should be familiar with the anatomy and physiology of the nose, pharynx, esophagus, and stomach when caring for clients with NG tubes. See Figure 5.1[2] for an illustration of the nasal cavity and pharynx.

The nares are the exterior openings to the nasal cavity. Usually, one nare is larger and more patent than the other. A septum, composed of bone and cartilage, divides the right and left nasal cavities. The nasal floor is parallel to the roof of the mouth. The end of the nasal cavity is narrow and ends at the juncture of several bones, including a portion of the cribriform plate, which is a very thin bone that, if fractured, could provide a direct portal into the brain. For this reason, NG tube placement in clients with suspected head trauma may be contraindicated.

The pharynx is a mucous membrane lined tube that begins at the nasal cavity and is divided into three major regions: the nasopharynx, the oropharynx, and the laryngopharynx.

- The nasopharynx serves only as an airway. It is a muscular passageway at the beginning of the pharynx, located behind the nasal cavity. It curves to extend behind the oral cavity to become the oropharynx.

- The oropharynx is a passageway for both air and food. The oropharynx is bordered superiorly by the nasopharynx and anteriorly by the oral cavity.

- The laryngopharynx is inferior to the oropharynx and posterior to the larynx. It continues the route for ingested material and air to the inferior end where the digestive and respiratory systems diverge. Anteriorly, the laryngopharynx opens into the larynx, and posteriorly it enters the esophagus that leads to the stomach. The larynx connects to the trachea and the lungs, so for this reason, great care must be taken when inserting an NG tube to ensure it enters the posterior laryngopharynx and goes into the esophagus, not anteriorly into the trachea and the lungs.

The epiglottis is a cartilaginous flap of connective tissue located at the entrance to the larynx. During swallowing, the larynx moves upward, and the epiglottis closes over the glottis to prevent aspiration of food and fluid into the trachea. Many clinicians use this natural movement during NG tube insertion by asking clients to swallow ice chips or water once the NG tube passes beyond the oropharynx (i.e., the back of the oral cavity). As the client swallows, the rising and falling of the larynx and the opening and closing of the epiglottis can assist passage of the NG tube beyond the laryngopharynx toward the esophagus. The nurse can request the client to tuck their chin to ease this passage.

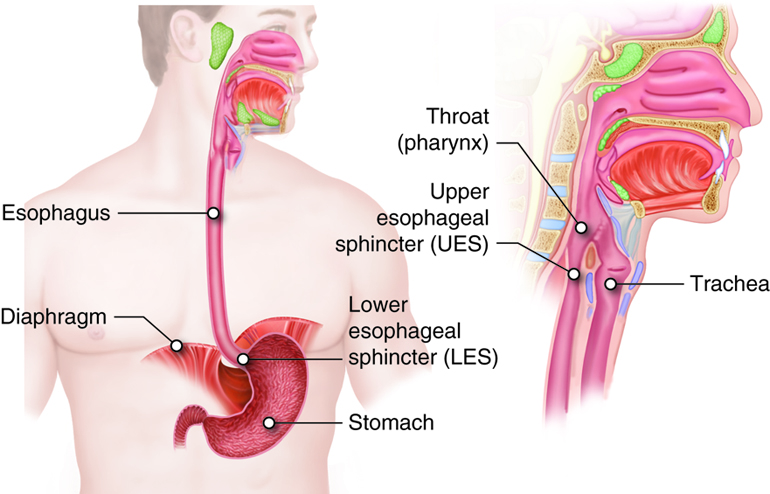

The esophagus starts at the upper esophageal sphincter and runs down through the diaphragm past the lower esophageal sphincter to the stomach. See Figure 5.2[3] for an illustration of the pharynx, trachea, esophagus, and stomach.

Indications for NG Tubes

These are the indications for NG tubes[4]:

- To decompress the stomach and gastrointestinal (GI) tract (i.e., to relieve distention due to bowel obstruction, ileus, or atony)

- To administer nutrition and/or medication

- To empty the stomach to prevent aspiration (for example, NG tubes may be inserted in intubated clients to prevent aspiration)

- To remove blood from clients with GI bleeding[5]

- To obtain a sample of gastric contents to assess bleeding, volume, or acid content

- To remove ingested toxins

- To give antidotes such as activated charcoal

- To give oral radiopaque contrast agents

- To provide bowel rest

Bowel Obstruction and Ileus

The most common indication for placement of a nasogastric tube is to decompress the stomach of a client with a distal bowel obstruction or ileus. Bowel obstruction is a mechanical blockage of intestinal contents by a mass, adhesion, hernia, impacted stool, or other physical blockage such as volvulus (i.e., twisting of the stomach or intestine) or intussusception (i.e., one segment of intestine telescopes inside another). Bowel obstructions block the normal passage of bodily fluids such as salivary, gastric, hepatobiliary, and enteric secretions, causing the fluids to build up, resulting in abdominal distension, pain, and nausea. Eventually, the fluids will build up to a point that nausea will progress to emesis, putting the client at risk for aspiration.[6]

Ileus occurs when there is a nonmechanical decrease or stoppage of the flow of intestinal contents. Ileus is often an unavoidable consequence of abdominal or retroperitoneal surgery but can also be found in severely ill clients with septic shock or mechanical ventilation. An ileus usually manifests itself from the third to the fifth day after surgery and usually lasts 2 to 3 days with the small bowel being the quickest to return to function (0 to 24 hours), followed by the stomach (24 to 48 hours), and lastly the colon (48 to 72 hours). Other causes of ileus may include the following[7]:

- Prolonged abdominal/pelvic surgery

- Lower gastrointestinal (GI) surgery

- Opioid use

- Intra-abdominal inflammation (sepsis/peritonitis)

- Peritoneal carcinoma

- Perioperative complications (pneumonia or abscess)

- Bleeding (intraoperative or postoperative)

- Hypokalemia

- Delayed enteral nutrition or nasogastric (NG) tube placement

NG tube placement is a temporary intervention for bowel obstruction and ileus when normal peristalsis is temporarily altered. It serves to decompress the stomach and keep it empty until normal peristalsis returns. If decompression is needed for more than six weeks, then something more permanent like a jejunostomy tube may be inserted.

Nutrition and Medication Administration

Nasogastric tubes may be placed to administer nutrition or medications for a client who has a functional GI tract but is unable to ingest, chew, or swallow food safely or in adequate amounts. This indication is common for clients who have suffered a cerebrovascular accident (i.e., stroke) that has left them unable to swallow effectively. Nasogastric tubes may be placed for nutritional support while waiting to see how much function the client will recover. If the client does not adequately recover their swallowing ability or will otherwise require long-term nutritional support, then a more permanent feeding tube is placed such as a gastrostomy or jejunostomy feeding tube.[8]

Other examples of conditions where clients have a functioning GI tract but cannot tolerate oral intake are as follows:

- Decreased level of consciousness, such as a coma or a sedated client on a ventilator

- Following upper gastrointestinal surgery where an anastomosis (i.e., a surgical connection between parts of the intestine) must be protected in the initial postoperative period

- During preoperative period to prepare malnourished clients for major abdominal surgery

For many of these indications for NG tubes, an orogastric tube (OG tube) can also be placed. Many of the principles used to manage an NG tube are the same for managing an OG tube, such as checking placement and monitoring for potential complications.

Contraindications for NG Tubes

There are two types of contraindications for any procedure or intervention and are referred to as absolute and relative. An absolute contraindication means the procedure or intervention may produce a life-threatening situation and should be avoided if possible. A relative contraindication means caution should be used because the possibility of an adverse event is possible; therefore, benefits must outweigh the risks.

Absolute contraindications to the placement of an NG tube include significant facial trauma; basilar skull fractures; or recent nasal, throat, or esophageal surgery where attempted placement of a tube via the nares may exacerbate the existing tissue trauma. In some cases of esophageal surgery, such as an esophagectomy, the surgeon will place the NG tube in the operating room and then remove it when indicated; the nurse should not manipulate the NG tube in this case. Esophageal obstruction, such as a neoplasm or foreign object, is also an absolute contraindication to nasogastric tube placement.[9]

Relative contraindications include esophageal trauma, especially if caustic substances were ingested. Coagulation abnormalities or anticoagulation therapy may cause bleeding from the tissue trauma from tube placement. For clients with previous gastric bypass surgery, hiatal hernia repair, or abnormal GI anatomy (such as esophageal varices or strictures), NG tubes should be placed by a provider under endoscopy.[10]

Types of NG Tubes

There are two basic types of NG tubes, those used for decompression and those used for feeding.

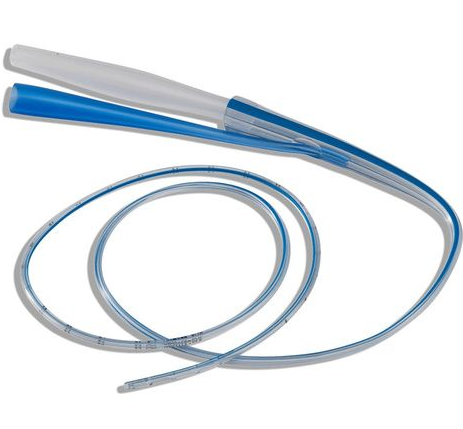

For decompression, a double-lumen, rigid tube is used with one large lumen used for suction and a smaller lumen to act as a sump. (A sump allows air to enter to prevent suctioning of the gastric mucosa into the eyelets at the distal tip of the tube or obstruction when the stomach is fully collapsed.) These tubes are often referred to as “Salem Sump.” Their bore size ranges from 6 to 18 French, with those most commonly inserted being 14 to 16 French. A blue pigtail on this type of tube is the air vent, so it should never be clamped, connected to suction, or used for irrigation. See Figure 5.3[11] for an image of a Salem Sump.

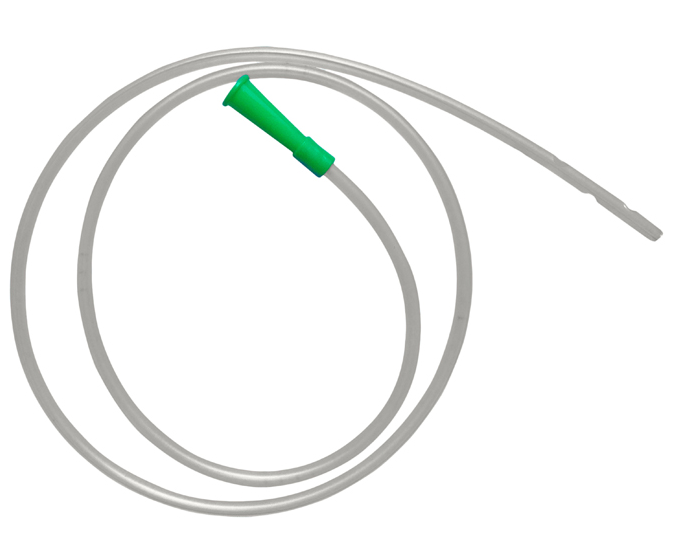

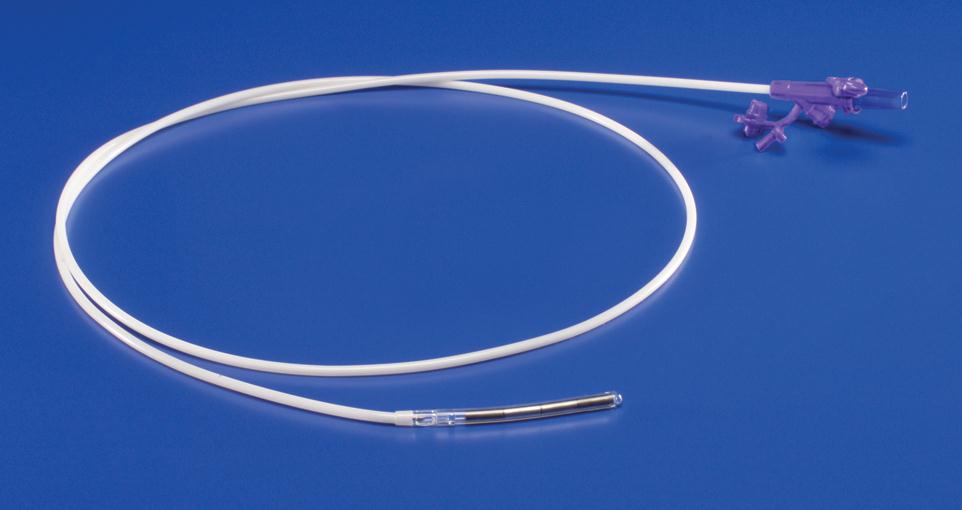

NG tubes used for administration of medications or feeding are single lumen and are softer than those used for decompression. They have a smaller bore with a size ranging from 8 to 12 French. NG tubes placed for feeding or medication administration may be a Levin tube or a Dobhoff tube. A Levin tube is a simple small diameter NG tube. A Dobhoff tube is a special type of NG tube that is small-bore and flexible, so it is more comfortable for the client than a standard NG tube. The tube is inserted with the use of a guide wire, called a stylet, that is removed after correct tube placement is confirmed. A Dobhoff tube also has weight on the end to allow gravity and peristalsis to help advance the end of the tube past the pylorus, providing an additional barrier to reduce aspiration risk of nutrition or medications administered. See Figure 5.4[12] for an image of a Levin tube and Figure 5.5[13] for an image of a Dobhoff tube.

NG Tube Insertion

Insertion of an NGT is typically a clean (not sterile), “blind” procedure, meaning the person performing the procedure can’t visualize where the tube is going in the client’s body as they are inserting it. Insertion involves passing the tube through the nose, along the nasal floor, through the pharynx and down the esophagus until the proximal tip of the tube rests in the client’s stomach. See “Checklist: Insert a Nasogastric Tube” for detailed procedural instructions.

NG tubes are inserted and removed by nurses and other health care providers. Due to the invasive nature of the placement process, privately ask the client if they desire visitors to leave the room during placement or removal of the NG tube. Nurses provide the daily care of NG tubes, as well as the administration of nutritional formulas, medications, and other substances through the tube. Nursing management of NG tubes are further described in the “Applying the Nursing Process” section of this chapter. The nurse is also responsible for verifying the NG tube has been accurately placed prior to initial use and before each use thereafter.[14]

Estimating the Depth of NG Tube Placement

Five to seven centimeters posterior to the nares, the nasal sinus connects to the nasopharynx. The length of the pharynx from the base of the skull to the start of the esophagus is 12 to 14 centimeters. The esophagus, from the upper esophageal sphincter to the stomach, is approximately 25 centimeters. The stomach is a highly distensible structure and can vary in length, but the empty stomach is typically about 25 centimeters long. Thus, approximately 55 centimeters of the NG tube is typically inserted in an adult.[15]

There are several methods used to estimate the depth that an NG tube should be placed. A common preprocedural maneuver used to estimate the length of the tube that should be inserted is to measure the tube from the tip of the client’s nose to the earlobe and then against the throat down to the xiphoid process, about 1/2 inch to 1 inch below the sternal notch.[16]

Special Circumstances

Insertion of weighted NG tubes used for feeding, as well as NG tubes for post-GI surgery clients, is performed by specially trained advanced practice nurses, physician assistants, or physicians.

The NG tube inserted for a post-GI surgery client should never be repositioned due to the risk of rupturing a suture line. If the NG tube becomes dislodged, the surgeon should be notified.

If a client is unconscious, gag reflex should be assessed before initiating the procedure. Flex their head forward with your nondominant hand during the procedure as the tube is passed through the larynx. Extra precautions must be taken for clients with head injury to avoid misplacement of the NG tube.

Request assistance prior to starting the procedure based on the client condition. For example, clients who are confused, anxious, at risk for pulling out the tube as it is being inserted, and children often require assistance. Additionally, for pediatric clients it is often helpful to have their parents or caregivers at the bedside. For infants, sucrose may be administered to alleviate discomfort, based on agency policy.

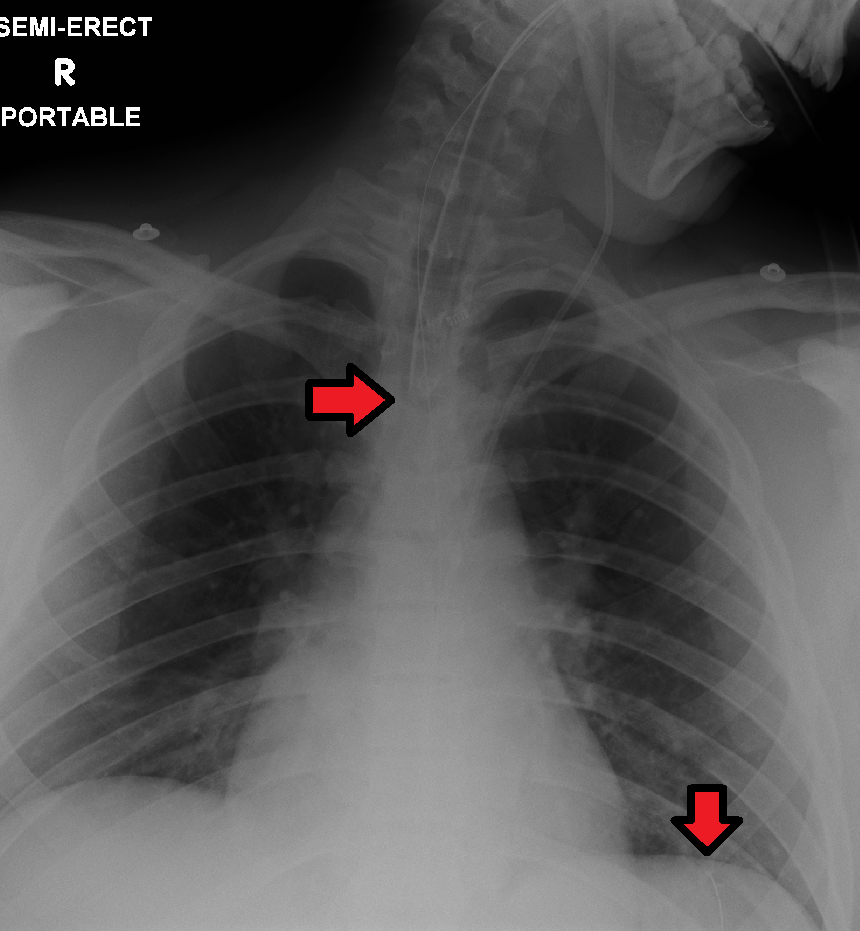

Verifying NG Tube Placement

Insertion of NG tubes is considered a simple procedure, but incorrect placement can lead to client harm and possibly death. The risk of harm and death increases when misplaced tubes are not identified prior to their use. For this reason, placement must be verified immediately after insertion by an X-ray to ensure it has not been inadvertently placed into the trachea and into the bronchi. The nurse should monitor for signs and symptoms of incorrect placement during the procedure, such as coughing, decreased pulse oximetry readings, and cyanosis. If these signs occur, the tube should immediately be withdrawn until normal breathing resumes. See Figure 5.6[17] for an image of an X-ray demonstrating correct placement of an enteral tube in the stomach as indicated by the lower red arrow. (This X-ray also demonstrates an endotracheal tube correctly placed in the trachea as indicated by the top arrow.) After X-ray verification, the tube should be marked with adhesive tape and/or a permanent marker to indicate the measurement on the tube where the feeding tube enters the nares or penetrates the abdominal wall. This number on the tube at the entry point should be documented in the medical record and communicated during handoff reports. At the start of every shift, the nurse should evaluate if the incremental marking or external tube length has changed. If a change is observed, bedside tests such as visualization or pH testing of tube aspirate can help determine if the tube has become dislodged. If in doubt, the provider should be notified and an X-ray repeated to confirm tube location.[18]

After the tube placement is initially verified by X-ray, it is possible for the tube to migrate out of position due to the client coughing, vomiting, and moving. For this reason, the nurse must routinely check tube placement before every use. The American Association of Critical‐Care Nursing recommends that the position of a feeding tube should be checked and documented every four hours and prior to the administration of enteral feedings and medications by measuring the visible tube length and comparing it to the length documented during X-ray verification.[19],[20],[21]

Older methods of verifying tube placement included observing aspirated GI contents or administering air into the tube with a syringe while auscultating (commonly referred to as the “whoosh test”). However, research has determined these methods are unreliable and should no longer be a sole method used to verify placement.[22],[23]

Assessing the pH of aspirated gastric contents is a method that may be used in conjunction with other methods to verify placement in some agencies. If used, gastric aspirate should have a pH of less than or equal to 5.5 using pH indicator paper that is marked for use with human aspirate. However, caution should be used with this method because enteral formula and some medications alter the gastric pH.[24] Therefore, pH testing should not be used as the sole method of verification but rather as part of a multi-step approach that may include radiographic confirmation or other agency-approved procedures.

Follow agency policy for assessing and documenting tube placement. Additionally, if the client develops respiratory symptoms that indicate potential aspiration, immediately notify the provider and withhold enteral feedings and medications until the placement is verified.

Potential Complications

The most common complications related to the placement of nasogastric tubes are discomfort, sinusitis, or epistaxis, all of which typically resolve spontaneously with the removal of the nasogastric tube.[25] Other complications associated with use of an NG tube range from minor to more severe and may include the following conditions:

- Trauma to the nares, larynx, esophagus, and/or stomach during insertion.

- Trauma to or erosion of gastric mucosa, especially if gastric suctioning is prolonged.

- Mucosal pressure injury of the nares.

- Placement-related issues: Inadvertent placement in the trachea that can lead to pleural injury, pneumothorax, tracheobronchial aspiration, pneumonia, and death. Respiratory distress is a medical emergency, and emergency assistance must be obtained immediately.

- Esophageal perforation, evidenced by neck or chest pain, dysphagia, dyspnea, subcutaneous emphysema, or hematemesis.

- Inadvertent intracranial placement through a fractured cribriform plate.

- Knotting of the NG tube around an endotracheal tube or retrograde positioning (i.e., the proximal tip of the tube curves upward through the esophagus).

- This work is a derivative of StatPearls by Sigmon and An and is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- “Blausen_0872_UpperRespiratorySystem.png” by Blausen.com staff (2014). “Medical gallery of Blausen Medical 2014” for WikiJournal of Medicine 1 (2). DOI:10.15347/wjm/2014.010. ISSN 2002-4436 is licensed under CC BY 3.0 ↵

- “D_M3_24.jpg” by unknown Cenveo is licensed under CC BY 3.0. Access for free at https://pressbooks.ccconline.org/bio106/chapter/digestive-structures-and-functions/ ↵

- This work is a derivative of StatPearls by Sigmon and An and is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- This work is a derivative of StatPearls by Sigmon and An and is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- This work is a derivative of StatPearls by Sigmon and An and is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- This work is a derivative of StatPearls by Beach and De Jesus and is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- This work is a derivative of StatPearls by Sigmon and An and is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- This work is a derivative of StatPearls by Sigmon and An and is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- This work is a derivative of StatPearls by Sigmon and An and is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- “11720205623covidien-salem-sump-nasogastric-suction-tube-P” by unknown author used on the basis of Fair Use. Access original image at https://www.healthproductsforyou.com/p-covidien-salem-sump-nasogastric-suction-tube.html?utm_source=google&utm_medium=surfaces&utm_campaign=shopping%20feed&utm_content=free%20google%20shopping%20clicks&gclid=Cj0KCQiAsdKbBhDHARIsANJ6-jcX4iGGwtT30nfQXurA9kiTlvlvBJQNj6BXyuGL4mGAnc40lL0tdCQaArZzEALw_wcB ↵

- “2-Levin-Tube.jpg” by unknown author is used under Fair Use. Access original image at https://www.smd-medical.com/product-detail/levin-tube-stomach-tube/ ↵

- “COV711006CN_PRI03.JPG” by unknown author is used under Fair Use. Access original image at https://punchout.medline.com/product/Kangaroo-Dobbhoff-Tip-Nasogastric-Feeding-Tube/Nasogastric-Tubes/Z05-PF10706 ↵

- Patient Safety Movement. (2020). Actionable patient safety solutions (APSS) #15: Nasogastric tube (NGT) placement and verification. https://patientsafetymovement.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/10/APSS-15-4.pdf ↵

- This work is a derivative of StatPearls by Sigmon and An and is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- Nasogastric or orogastric tube insertion. (2021). Lippincott procedures. http://procedures.lww.com ↵

- “ETTubeandNGtubeMarked.png” by James Heilman, MD is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0 ↵

- Boullata, J. I., Carrera, A. L., Harvey, L., Escuro, A. A., Hudson, L., Mays, A., McGinnis, C., Wessel, J. J., Bajpai, S., Beebe, M. L., Kinn, T. J., Klang, M. G., Lord, L., Martin, K., Pompeii‐Wolfe, C., Sullivan, J., Wood, A., Malone, A., & Guenter, P. (2017). ASPEN safe practices for enteral nutrition therapy. Journal of Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition, 41(1), 15-103. https://doi.org/10.1177/0148607116673053 ↵

- Boullata, J. I., Carrera, A. L., Harvey, L., Escuro, A. A., Hudson, L., Mays, A., McGinnis, C., Wessel, J. J., Bajpai, S., Beebe, M. L., Kinn, T. J., Klang, M. G., Lord, L., Martin, K., Pompeii‐Wolfe, C., Sullivan, J., Wood, A., Malone, A., & Guenter, P. (2017). ASPEN safe practices for enteral nutrition therapy. Journal of Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition, 41(1), 15-103. https://doi.org/10.1177/0148607116673053 ↵

- Lemyze, M. (2010). The placement of nasogastric tubes. CMAJ: Canadian Medical Association Journal, 182(8), 802. https://doi.org/10.1503/cmaj.091099 ↵

- Simons, S. R., & Abdallah, L. M. (2012). Bedside assessment of enteral tube placement: Aligning practice with evidence. American Journal of Nursing, 112(2), 40-46. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.naj.0000411178.07179.68 ↵

- Boullata, J. I., Carrera, A. L., Harvey, L., Escuro, A. A., Hudson, L., Mays, A., McGinnis, C., Wessel, J. J., Bajpai, S., Beebe, M. L., Kinn, T. J., Klang, M. G., Lord, L., Martin, K., Pompeii‐Wolfe, C., Sullivan, J., Wood, A., Malone, A., & Guenter, P. (2017). ASPEN safe practices for enteral nutrition therapy. Journal of Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition, 41(1), 15-103. https://doi.org/10.1177/0148607116673053 ↵

- Simons, S. R., & Abdallah, L. M. (2012). Bedside assessment of enteral tube placement: Aligning practice with evidence. American Journal of Nursing, 112(2), 40-46. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.naj.0000411178.07179.68 ↵

- Best, C. (2019). Selection and management of commonly used enteral feeding tubes. Nursing Times, 115(3), 43-47. https://www.nursingtimes.net/clinical-archive/nutrition/selection-and-management-of-commonly-used-enteral-feeding-tubes-18-02-2019/ ↵

- This work is a derivative of StatPearls by Sigmon and An and is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

A flexible plastic tube inserted through a nostril, down the posterior oropharynx, and into the stomach or the upper portion of the small intestine.

A mechanical blockage of intestinal contents by a mass, adhesion, hernia, impacted stool, or other physical blockage such as volvulus.

A nonmechanical decrease or stoppage of the flow of intestinal contents.

A surgical connection between parts of the intestine.