4.3 Applying the Nursing Process

Ongoing nursing assessments and interventions are essential to provide safe, quality care when a client has a CVAD. These actions are guided by evidence-based practice standards. In acute care and outpatient settings, the overall goals of CVAD infusion therapy are safe administration of medications and the absence of complications.

Nurses provide routine care and maintenance of CVADs after their insertion, including the following responsibilities:

- Providing for ongoing assessment of the insertion site and the infusion system to ensure it is functioning as expected

- Performing CVAD dressing changes while ensuring catheter stabilization

- Accessing CVADs

- Performing intravenous line care and management

- Flushing and locking CVADs

- De-accessing inserted and implanted CVADs

- Performing blood sampling from a CVAD

The nurse may also be involved in other activities related to safe use of CVADs such as culturing for suspected infections and advocating for catheter removal as soon as it is no longer indicated for treatment. In home care and outpatient settings, the nurse also provides education to the client and their family members on how to safely manage the CVAD and when to call the provider with concerns.

Assessment

The nurse must be knowledgeable about the different types and placement locations of CVADs as described in Table 4.2a in the “Basic Concepts” section. Regardless of which type of CVAD device is used, the nurse must routinely assess the site and dressing for integrity, signs of infection, catheter migration, and other signs of complications. Areas beyond the site of insertion must also be assessed, such as the adjacent skin, neck, chest area, and the extremity on the side where the central line is placed. If the catheter is tunneled under the skin, assessment also includes monitoring for pain, swelling, drainage, or erythema. External length is measured at the time of insertion and used for future measurement comparison. If a PICC line is in place, arm circumference is also measured each shift and results compared to previous readings. If arm circumference consistently increases, a deep vein thrombosis may be suspected.

The frequency of site assessment is dependent on the client’s condition and agency policies. Typically, in the acute care setting, site assessment is performed every shift. If the client is in the home care setting, they are educated on how to inspect their site and how frequently this assessment should occur. Home health nurses will assess the site and upper arm circumference during each visit.

Accurate documentation of site assessment and related monitoring are essential. Documentation of the assessment in the client’s medical record should include CVAD location, type of dressing, site assessment specifics, presence of any complications, and any actions or interventions performed. Table 4.3a summarizes the assessments related to CVADs.

Table 4.3a Summary of CVAD Assessments

| Assessment*

*Assessment of the CVAD should occur at least once every shift and as needed in acute care settings. |

Description |

| Assess the entire infusion system. | A complete assessment includes the insertion site and surrounding area, securement device, functioning of the CVAD, and tip location. |

|---|---|

| Assess for proper functioning of the device. | Observe for constant flow of fluids, high pressure, or occlusion alarms. Assess for blood flow. |

| Inspect the CVAD dressing. | Determine if the dressing is clean, intact, and dated. |

| Inspect and palpate the insertion site and surrounding area through the intact dressing. | Check for redness, bluish discoloration on darker skin, swelling, drainage, or a palpable cord. Ask the client if they are experiencing any pain, paresthesia, numbness, or tingling around the area. |

| Measure the external catheter length. | Compare the measurement results to the initial placement verification results to detect any catheter migration or dislodgement. |

| Measure the upper arm circumference for PICC lines. | Monitor circumference measurements each shift and compare results. Increasing measurements may indicate possible edema and deep vein thrombosis (DVT). Measurement of the arm circumference should occur 10 cm above the antecubital fossa and compared to the baseline measurement. A 3 cm increase in the circumference may indicate edema associated with a DVT. |

| Ensure correct labeling of all infusing fluids. | Follow agency policy and procedures for labeling infusing IV fluid and medications. |

| Ensure all luer-lock connections are secure. | Secure connections provide safety in guarding against microorganism and air entrance into the closed system, as well as leakage of medications out of the system. |

| Document the complete assessment in the client EMR. | Complete assessment documentation helps support QSEN or other quality and safety standard informatics. |

CVAD Dressing Changes and Site Care

CVAD dressing changes should occur routinely at established intervals according to evidence-based guidelines and agency policies. Many agencies have designated CVAD dressing kits. The dressing protects the insertion site and surrounding tissue from microorganism growth that can accumulate within CVAD hubs and the skin and cause a CLABSI.[1] Ensuring a clean, dry, and intact dressing helps prevent microorganisms from entering the bloodstream.

If the integrity of the CVAD dressing is compromised by moisture or drainage, becomes loose, or if signs of infection are apparent, the dressing should be replaced immediately. The dressing should be labeled with the date, time, and initials of the person completing the task. All CVAD dressing changes should be documented in the client’s medical record per agency policy.

CVAD site care is routinely performed, typically at the same time as the dressing change. Aseptic technique is required when providing site care and dressing changes with meticulous hand hygiene, sterile gloves, and a mask. The preferred skin disinfectant is 2% chlorhexidine for a client older than two months of age.[2] Chlorhexidine skin disinfectant provides antibacterial activity that persists for several hours after it is applied.

Implanted ports require dressings until the area is healed after the port has been implanted under the skin, as well as when accessing the port for intermittent and/or continuous infusions. A specialized noncoring needle is used when accessing implanted ports. (Refer to specific information on “Accessing and De-Accessing an Implanted Venous Access Device” later in this section.)

The dressing regimen for tunneled catheters within the acute care setting is typically the same as for nontunneled catheters. However, if the tunneled area is well-healed, a dressing may not be required in the outpatient setting.

There are different types of dressings that may be selected for a CVAD dressing change based on client status, agency policy, and evidence-based guidelines. Transparent semipermeable membrane (TSM) or simple gauze dressings are commonly used. Because TSM dressings are transparent, they allow visualization and inspection of the site area without removing or disturbing the dressing. They are also cost-effective and promote a closed system. Gauze dressings are commonly used for clients who perspire excessively, which interferes with a TSM dressing staying in place. A gauze dressing is also appropriate if the site is draining or if the person has a sensitivity to the transparent dressing.

Per CDC guidelines and infusion nursing’s standards of practice, TSM dressings should be changed at a minimum of every seven days, whereas gauze dressings must be changed at least every 48 hours. Dressings must also be changed as needed, such as for loss of dressing integrity, the presence of drainage or moisture, or signs of infection.[3]

TSM dressings with an impregnated chlorhexidine gel or disc are a newer technology that are becoming more commonly used. An antiseptic foam disc is placed around the catheter insertion site and covered with a TSM dressing. Other TSM dressings have an impregnated chlorhexidine gel within the dressing that is placed over the catheter insertion site. The CDC has not yet made a recommendation regarding use of impregnated dressings.[4] See Figure 4.8[5] for an image of a quad lumen CVAD with an impregnated chlorhexidine disc, subcutaneous and adhesive external securement device (ESD), and bordered semipermeable dressing. In practice, all access ports would have sterile caps attached according to evidence-based practices for infection control.

Before performing a CVAD dressing change, review the client’s medical record for previous history, allergies (including allergies to tape or adhesives), previous or baseline length and circumference measurements, and the type of dressing used. Most acute care settings utilize a central line dressing kit that includes standardized accessories necessary for the procedure.

When performing CVAD dressing changes, using aseptic nontouch technique (ANTT) is considered a global standard. The "ANTT approach" identifies key parts and key sites throughout the preparation and implementation of the procedure. A key part is any sterile part of equipment used during an aseptic procedure, such as needle hubs and dressings. A key site is the insertion site, nonintact skin, or an access site for medical devices connected to clients. CVAD insertion sites are considered key sites. ANTT includes four underlying principles to keep in mind while performing invasive procedures:

- Always perform meticulous hand hygiene.

- Never contaminate key parts or key sites.

- Touch nonkey parts with confidence.

- Take appropriate infection control precautions.

Review Table 4.3b for a summary of CVAD dressing change steps and their rationale.

Table 4.3b CVAD Dressing Change Steps

| Step |

|---|

Follow standard aseptic nontouch technique (ANTT). Standard ANTT requires the use of a general aseptic field, such as a single use or disinfected surface for placement of all needed supplies to provide a controlled workspace and to promote asepsis. Apply PPE according to the client’s health conditions. The client and the RN both wear a mask during a dressing change to prevent contamination of the site area. Ask the client to turn their head in the opposite direction of the dressing change site to avoid potential contamination of the site.

|

| Nonsterile gloves are acceptable when removing a CVAD dressing. When removing the dressing, carefully roll up the edges and remove toward the insertion of the catheter to prevent dislodgement. After removing the dressing, remove the nonsterile gloves, perform hand hygiene, and don sterile gloves. |

| Most securement devices are integrated within the CVAD dressing kit and are changed with the dressing. If the catheter is secured with sutures, gently and carefully lift the suture plate to cleanse with agency-approved antiseptic, maintaining aseptic technique. |

| Cleanse the insertion site and surrounding skin with each dressing change using aseptic technique. Using chlorhexidine solution is considered standard practice, but if the client has an allergy or hypersensitivity to its use, povidone-iodine may be used as an alternative. A single-use antiseptic applicator is commonly used. When cleansing, do so in a back-and-forth motion for 30 seconds and allow it to dry. If dry blood or drainage is present on the skin and around the insertion site, it should be cleansed and removed using sterile technique prior to applying a new dressing. |

Label the dressing with the date, time, and your initials, as well as the date the dressing should be changed again.

|

Document the related assessments, cleansing, and dressing change in the client’s medical record.

|

Accessing CVADs

Each time a CVAD is accessed, there is a chance for exposure to microorganisms from the clinician, the environment, or the client. To reduce this exposure, accessing and manipulations of a CVAD should be kept at a minimum. Adhering to strict hand hygiene and ANTT standards are important strategies to reduce the risk of infection.

When accessing a CVAD, the CVAD access hub or needleless port must be decontaminated with a vigorous scrub technique with a single-use aseptic swab or a scrub hub. A scrub hub is a specific scrubbing device for CVAD hubs and embedded with chlorhexidine and alcohol or 70% alcohol to disinfect catheter hubs or needleless connectors. The suggested scrub time is up to 60 seconds with a minimum of 15 seconds. When decontaminating the hub, generate friction by scrubbing in a twisting motion like juicing an orange. Ensure the top of the hub is scrubbed, as well as the sides.[6]

An alternative to aseptic swabs or scrub hubs is aseptic-impregnated catheter hub protective caps. These caps contain a sponge that is saturated with alcohol or chlorhexidine. They are attached to the access ports and eliminate the need to perform the vigorous scrub. After the caps are removed, they are discarded, and a new sterile cap is applied.

Flushing and Locking CVADs

Flushing is a manual injection of 0.9% sodium chloride to clean the lumen of the catheter. Locking is the injection of a limited volume of a liquid following the catheter flush, for the period of time when the catheter is not used, to prevent intraluminal clot formation and/or catheter colonization.[7]

CVADs require flushing to maintain patency of the line(s) and to prevent the mixing of incompatible solutions and/or medications. The recommended flush is sterile 0.9% sodium chloride unless manufacturer or agency policy requires flushing with an alternate solution.

Central line catheters are flushed according to agency policy. They must be flushed immediately after placement of the initial insertion has been verified, before and after each fluid or medication infusion, and before and after drawing blood from the central line. Additionally, flushing of all lumens of a multi-lumen catheter should be considered after obtaining blood samples to reduce the possibility of blood influx into other lumens due to changing intraluminal pressure. If a CVAD is not being routinely accessed, it is typically flushed and locked every seven days. Implantable ports that are not being accessed should be flushed and locked every 4-6 weeks.[8]

A 10-mL or larger syringe is used to access a CVAD to prevent excess pressure that can damage the lumen. Before flushing the lumen with 0.9% sodium chloride, aspiration of blood should be attempted to ensure patency. The volume of fluid used for flushing should be twice the volume of the lumen.

Instilling the flush fluid into the catheter lumen allows a column of fluid to maintain its patency. A pulsatile flushing technique is recommended with ten small boluses of 1 mL of fluid interrupted by brief pauses. This technique has been found to be more effective at removing solid deposits (such as fibrin, drug participate, or intraluminal bacteria) compared to continuous low flow techniques.[9] Flushing should never occur if force is required against resistance because this can cause rupture of the catheter or mobilization of an occlusive clot.

If resistance is met while flushing or there is inadequate blood return on aspiration, troubleshoot for potential causes and solutions such as repositioning or removing kinks in lines. If these initial steps are not successful, follow agency policy in using a thrombolytic medication (i.e., alteplase) or requesting an order for a port study or central line study with fluoroscopy.

There are different types of needleless connectors through which the CVAD is flushed. If using a negative needleless connector, clamp the lumen while injecting the last 0.5 mL and before the syringe is disconnected to prevent blood reflux back into the catheter tip when the syringe is disconnected. If using a positive needleless connector, clamp after the syringe is disconnected to allow the internal mechanism to activate. For neutral (anti-reflux) needleless connectors, there is no specific clamping procedure required.

Instilling a “locking” fluid into a CVAD catheter causes a column of fluid within the catheter to maintain patency. Recommendations regarding the type of locking solution to use vary. Some studies suggest 0.9% normal saline is as effective as heparin. Follow agency policy and recommendations from the manufacturer.[10]

Standard ANTT (Aseptic Nontouch Technique) is used when flushing and locking central lines, as well as when infusing other fluids and medications. ANTT requires use of meticulous hand hygiene and a single use or disinfected surface for placement of all supplies to provide a controlled workspace and promote asepsis.[11]

Accessing and De-Accessing an Implanted Venous Access Device

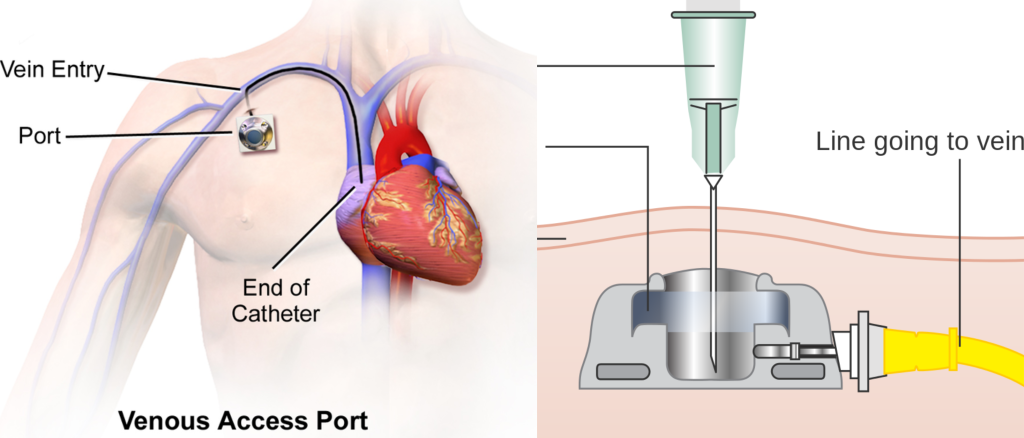

The management and care of an implanted venous access device (IVAD), as recommended by the CDC, includes utilizing proper aseptic technique before palpating, accessing, or performing dressing changes. See Figure 4.9[12] for an image of an IVAD that has been placed.

When accessing an IVAD, the skin at the site of access must be disinfected with chlorhexidine solution and allowed to dry before accessing the device. Many clients require a lidocaine medication (i.e., EMLA cream or intradermal lidocaine injection) prior to port access to prevent pain. This is especially true for vulnerable populations requiring IVADs such as pediatric, elderly, and oncology clients.

A noncoring needle must be used for accessing IVADs to prevent damage to the device. See Figure 4.10[13] for images related to accessing an IVAD.

Some IVADs are “power-injectable” while others are not. This means that some ports can tolerate the pressure required for CT injectable dye while others cannot. The type of needle used to access the port depends on what type of port the client has implanted. Clients with a power-injectable port should have an ID card, bracelet, and some type of identifier. This information should also be recorded in the medical record. If no information is available, the port should be treated as a nonpower injectable port and accessed with a normal port needle and not used for CT dye.

As with all long-term vascular access devices, IVADs are at risk for occlusion or loss of patency because protein buildup can occur on the inner surface of the device. Flushing and locking implanted ports help to prevent occlusion, but there are no clear recommendations for standardized flushing techniques or volumes. Recommendations from the manufacturers vary with the type of device regarding the use of heparin or saline. Flushing guidelines are typically established by the manufacturer and agency policy.[14] Currently, the consensus of recommendations for flushing implanted ports that are used a minimum of every 8 hours in adult clients is to flush after each infusion of medication or blood administration with 10 mL of 0.9% normal saline or every 24 hours according to the manufacturer’s recommendations.

The majority of techniques that are used for locking IVADs consist of withdrawing the syringe while still applying positive pressure during the injection of the last 0.5 mL of fluid volume. The volume used for locking depends on the reservoir volume and catheter diameters. Formal recommendations for maintenance locking in implanted ports are to flush with 10 mL 0.9% normal saline every four weeks in closed ports. For open-implanted ports, the recommendation is to flush with 10 mL normal saline followed by 5 mL heparin every four weeks.[15] The dose of heparin required to maintain patency can vary from 10 to 1,000 iU/mL, with the concentration of 100 IU/mL in a volume of 3 mL the most commonly used.[16]

Current recommendations for the maintenance of implanted ports indicate the needle should be changed and the port accessed every seven days.[17]

View a supplementary YouTube video[18] on CVAD access and care: Ports: Access and Care.

Blood Sampling From a CVAD

Obtaining a blood sample from a CVAD is a responsibility of the registered nurse. Multiple venipunctures frequently occur in acute care settings due to the severity of the medical condition in a client who requires a CVAD. The main advantage of using a CVAD for frequent blood sampling is decreased pain and anxiety compared to the experience of multiple peripheral venipunctures. However, accessing CVADs also has potential risks associated with infection, occlusion, and improper sample taking, resulting in inaccurate test results. Following evidence-based infection prevention practices, limiting the frequency of blood sampling, and following ANTT guidelines help reduce the risk of infection. A summary of key points related to blood sampling from CVADs is outlined in Table 4.3d. See the “Checklist: Obtain a Blood Sample From a CVAD” for the complete steps for this procedure. Note that current guidelines recommend to not use CVADs infusing parental nutrition for blood sampling because manipulation may increase the risk for CLABSI.[19]

![]() During the blood sampling procedure, if any signs or symptoms occur indicating an air embolism, place the client on the left side in Trendelenburg or left lateral decubitus position, call the rapid response team, and notify the provider.

During the blood sampling procedure, if any signs or symptoms occur indicating an air embolism, place the client on the left side in Trendelenburg or left lateral decubitus position, call the rapid response team, and notify the provider.

Table 4.3d Summary of Key Points Related to Blood Sampling From a CVAD

| Steps | Rationale |

|---|---|

| Stop the infusion of fluids and medications into the catheter’s lumens. | Stopping the infusion of fluids or medications prevents these substances from interfering with the blood sample. Current guidelines do not specify a standard length of time for stopping the infusion, but it is associated with the internal volume of the specific CVAD.[20] |

| Choose the appropriate CVAD lumen for obtaining samples based on the largest lumen or the configuration of the lumen exit sites. | Blood draw requires a large lumen. For catheters with a staggered lumen exit at the tip, the sample should be drawn from the lumen exiting at the point farthest away from the heart and above other lumen exits used for infusion.[21] Follow CVAD manufacturer’s instructions for these decisions. |

| Vigorously scrub the needless connector for at least 15 seconds with antiseptic scrub and let it dry completely.[22] | Scrubbing prevents microorganism contamination, and drying prevents contamination by substances. |

| Attach a prefilled 10-mL syringe of preservative-free normal saline to the needleless connector using ANTT. Unclamp the catheter and thoroughly flush the lumen with 10-20 mL of preservative-free 0.9% normal saline.[23] Aspirate slowly for blood, noting the characteristics of the whole blood. | A 10-mL syringe generates lower pressure within the catheter and prevents lumen rupture and/or occlusion. |

| Clear the dead space by using the push-pull method or discarding the aspirated blood according to agency policy. The discard method requires initial aspiration of 2 to 25 mL of blood (per internal volume of the CVAD, saline flushing prior to drawing the discard volume, and specific laboratory tests needed) and then discarding the syringe before performing the blood sampling.[24] The push-pull method utilizes the same syringe used when aspirating to test patency of the catheter. With the syringe still attached, 4 mL to 6 mL of blood is aspirated and then pushed back into the catheter. This aspiration and reinfusion sequence is repeated for four cycles. The blood and syringe are then discarded.[25] | Either method clears the CVAD catheter’s dead space volume and removes any of the blood that becomes diluted with the flush solution. Performing the push-pull method for four cycles allows for an accurate blood sample and also reduces phlebotomy-associated blood loss, particularly when obtaining multiple blood samples. For the discard method, coagulation studies require the largest discard volume to produce accurate results, but this volume of discarded blood can lead to hospital-acquired anemia. |

| After obtaining the blood sample, thoroughly flush the CVAD lumen with 10-20 mL of preservative-free 0.9% normal saline.[26] | Flushing thoroughly prevents occlusion. |

Evaluation

Daily evaluation for the necessity of continuing the CVAD is important and supported by the CLABSI prevention guidelines. Evaluating the client’s cardio-respiratory status every shift and as needed per client condition prompts early recognition of potential complications.

Clients who are receiving infusion therapy and/or medication treatment require ongoing monitoring of laboratory values, intake/output, daily weights, and vital signs to evaluate their current fluid and electrolyte balances.

Nurses also evaluate the client’s understanding of the CVAD. If the client will be discharged home with an IVAD, it is imperative they understand how to manage their device safely and when to notify the provider. They will also need referrals to a home health agency, as well as supplies to manage the device on an outpatient basis, such as extra dressings, flushes, and tubing.

- NSW Agency for Clinical Innovation. (2021). Central venous access devices (CVAD): Clinical practice guide. Agency for Clinical Innovation. https://aci.health.nsw.gov.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0010/239626/ACI-CVAD-clinical-practice-guide.pdf ↵

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2015, November 5). Summary of recommendations: Guidelines for the prevention of intravascular catheter-related infections (2011). https://www.cdc.gov/infectioncontrol/guidelines/bsi/recommendations.html ↵

- Gorski, L. (2021). A look at 2021 infusion therapy standards of practice. Home Healthcare Now, 39(2), 62-71. https://www.nursingcenter.com/wkhlrp/Handlers/articleContent.pdf?key=pdf_01845097-202103000-00002 ↵

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2015, November 5). Summary of recommendations: Guidelines for the prevention of intravascular catheter-related infections (2011). https://www.cdc.gov/infectioncontrol/guidelines/bsi/recommendations.html ↵

- “ID-112-CVAD-IJ-CICC-Oct-2020-2.jpeg” by E. Alexandrou used with permission. Access the original image at https://www.eviq.org.au/clinical-resources/central-venous-access-devices-cvads/112-central-venous-access-devices#short-term-cvads ↵

- The Joint Commission. (2023). Central line-associated bloodstream infection toolkit and monograph. https://www.jointcommission.org/resources/patient-safety-topics/infection-prevention-and-control/central-line-associated-bloodstream-infections-toolkit-and-monograph/ ↵

- Godelieve, A. G. (2015). Flushing and locking of venous catheters: Available evidence and evidence deficit. Nursing Research and Practice, 2015. https://doi.org/10.1155/2015/985686 ↵

- Gorski, L. A., Hadaway, L., Hagle, M. E., Broadhurst, D., Clare, S., Kleidon, T., Meyer, B. M., Nickel, B., Rowley, S., Sharpe, E., & Alexander, M. (2021). Infusion therapy standards of practice (8th ed.). Journal of Infusion Nursing: The Official Publication of the Infusion Nurses Society, 44(1S Suppl 1), S1–S224. https://doi.org/10.1097/NAN.0000000000000396 ↵

- Gorski, L. A., Hadaway, L., Hagle, M. E., Broadhurst, D., Clare, S., Kleidon, T., Meyer, B. M., Nickel, B., Rowley, S., Sharpe, E., & Alexander, M. (2021). Infusion therapy standards of practice (8th ed.). Journal of Infusion Nursing: The Official Publication of the Infusion Nurses Society, 44(1S Suppl 1), S1–S224. https://doi.org/10.1097/NAN.0000000000000396 ↵

- Gorski, L. (2021). A look at 2021 infusion therapy standards of practice. Home Healthcare Now, 39(2), 62-71. https://www.nursingcenter.com/wkhlrp/Handlers/articleContent.pdf?key=pdf_01845097-202103000-00002 ↵

- Gorski, L. (2021). A look at 2021 infusion therapy standards of practice. Home Healthcare Now, 39(2), 62-71. https://www.nursingcenter.com/wkhlrp/Handlers/articleContent.pdf?key=pdf_01845097-202103000-00002 ↵

- “Port-catheter.jpg” by Una Smith (talk) is licensed under CC0 ↵

- “Diagram_showing_an_implantable_port_under_the_skin_CRUK_100.svg” by Cancer Research UK and “Venous_Access_Port_Catheter.png” by BruceBlaus are both licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0 ↵

- Blanco-Guzman, M. O. (2018). Implanted vascular access device options: A focused review on safety and outcomes [Review]. Transfusion, 58, 558-568. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/pdfdirect/10.1111/trf.14503 ↵

- Blanco-Guzman, M. O. (2018). Implanted vascular access device options: A focused review on safety and outcomes [Review]. Transfusion, 58, 558-568. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/pdfdirect/10.1111/trf.14503 ↵

- Oliveira, F. J. G., Rodrigues, A. B., Ramos, I. C., & Caetano, J. Á. (2020). Dosage of heparin for patency of the totally implanted central venous catheter in cancer patients. Revista Latino-Americana de Enfermagem, 28, e3304. https://doi.org/10.1590/1518-8345.3326.3304 ↵

- Oncology Nursing Society. (2017). Access device standards of practice for oncology nursing. https://www.ons.org/books/access-device-standards-practice-oncology-nursing ↵

- Moffott Cancer Center. (2018, October 31). Ports: Access and care [Video]. YouTube. All rights reserved. https://youtu.be/KtCwEdQbPRQ ↵

- Gorski, L. (2021). A look at 2021 infusion therapy standards of practice. Home Healthcare Now, 39(2), 62-71. https://www.nursingcenter.com/wkhlrp/Handlers/articleContent.pdf?key=pdf_01845097-202103000-00002 ↵

- Gorski, L. (2021). A look at 2021 infusion therapy standards of practice. Home Healthcare Now, 39(2), 62-71. https://www.nursingcenter.com/wkhlrp/Handlers/articleContent.pdf?key=pdf_01845097-202103000-00002 ↵

- Gorski, L. (2021). A look at 2021 infusion therapy standards of practice. Home Healthcare Now, 39(2), 62-71. https://www.nursingcenter.com/wkhlrp/Handlers/articleContent.pdf?key=pdf_01845097-202103000-00002 ↵

- The Joint Commission. (2023). Central line-associated bloodstream infection toolkit and monograph. https://www.jointcommission.org/resources/patient-safety-topics/infection-prevention-and-control/central-line-associated-bloodstream-infections-toolkit-and-monograph/ ↵

- Gorski, L. (2021). A look at 2021 infusion therapy standards of practice. Home Healthcare Now, 39(2), 62-71. https://www.nursingcenter.com/wkhlrp/Handlers/articleContent.pdf?key=pdf_01845097-202103000-00002 ↵

- Gorski, L. (2021). A look at 2021 infusion therapy standards of practice. Home Healthcare Now, 39(2), 62-71. https://www.nursingcenter.com/wkhlrp/Handlers/articleContent.pdf?key=pdf_01845097-202103000-00002 ↵

- McBride, C., Miller-Hoover, S., & Proudfoot, J. A. (2018). A standard push-pull protocol for waste-free sampling in the pediatric intensive care unit. Journal of Infusion Nursing: The Official Publication of the Infusion Nurses Society, 41(3), 189–197. https://doi.org/10.1097/NAN.0000000000000279 ↵

- Gorski, L. (2021). A look at 2021 infusion therapy standards of practice. Home Healthcare Now, 39(2), 62-71. https://www.nursingcenter.com/wkhlrp/Handlers/articleContent.pdf?key=pdf_01845097-202103000-00002 ↵

An aseptic nontouch technique reflecting the global standard for an invasive procedure.

Any sterile part of equipment used during an aseptic procedure, such as needle hubs and dressings.

The insertion site, nonintact skin, or an access site for medical devices connected to clients.

A specific scrubbing device for CVAD hubs and embedded with chlorhexidine and alcohol or 70% alcohol to disinfect catheter hubs or needleless connectors.

Caps contain a sponge that is saturated with alcohol or chlorhexidine.

A manual injection of 0.9% sodium chloride to clean the catheter.

The injection of a limited volume of a liquid following the catheter flush, for the period of time when the catheter is not used, to prevent intraluminal clot formation and/or catheter colonization.