3.2 Basic Concepts

Compatibility and Blood Types

ABO Antigen Markers

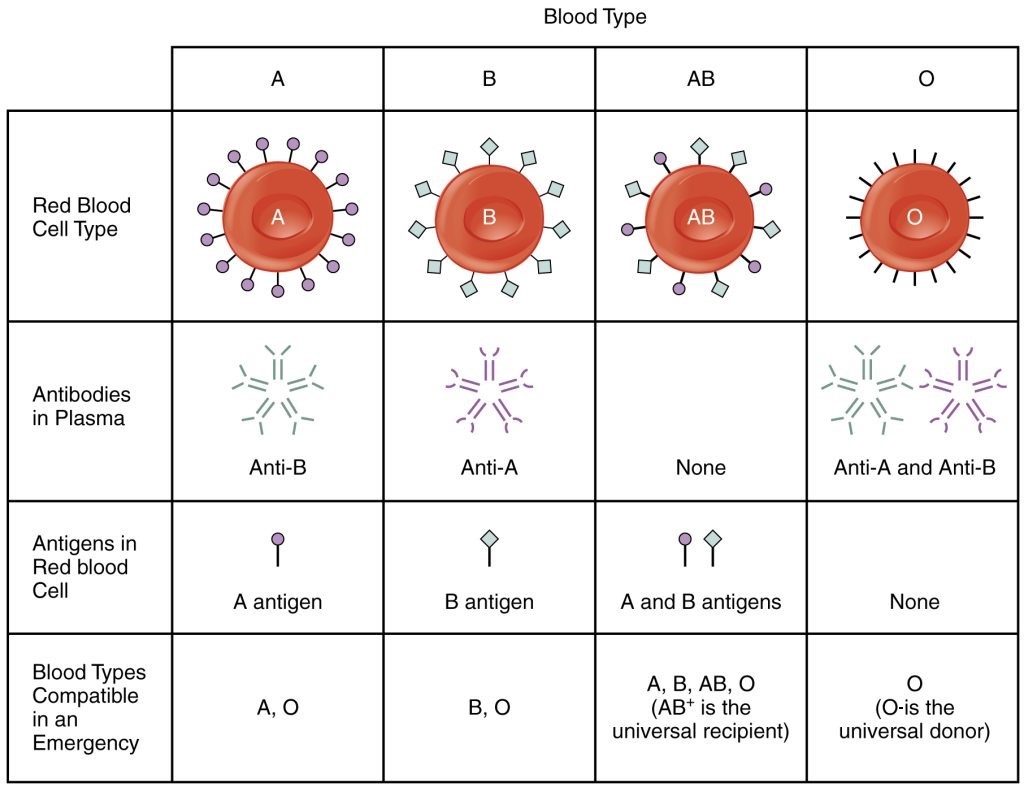

There are four main types of blood groups based on antigens on the surface of red blood cells. Some of these antigens are also present on platelets and in other tissues in the body. The ABO system uses the presence or absence of these specific antigens to identify four main blood groups: A, B, AB, and O. See Figure 3.1[1] for an illustration of ABO antigens and blood groups.

In addition to the antigens present on the red blood cell, people in certain blood groups have naturally occurring antibodies in the serum against the antigens they don’t have. For example, people with blood type A have anti-B antibodies, people with blood type B have anti-A antibodies, people with blood type O have anti-A and anti-B antibodies, and people with AB blood type have no anti-A or anti-B antibodies. For these reasons, the presence of antigens on a person’s red blood cells dictates the type of blood they can receive. However, type O blood does not have an antigen, so it can be given to a person with any blood type. As a result, people with type O negative blood are often referred to as “universal blood donors.” Likewise, people with type AB positive blood are referred to as “universal recipients” because they can receive blood from any blood type.

If a person receives blood that is not compatible with their blood type, red cell destruction called hemolysis occurs. ABO incompatibility can cause significant transfusion reactions that can be fatal. Nurses play a major role in safe blood product transfusions and constitute the last link in the chain of the transfusion process to ensure incompatible blood types are not administered and patients are closely monitored for transfusion reactions.[2]

Rh Factor

In addition to ABO blood types, another major consideration for compatibility of blood products is the person’s Rh factor. There are over 50 Rh antigens, and five are most antigenic. The most important Rh factor is D, located on the surface of the red blood cell. If a person has the D antigen, they are referred to as “Rh positive” or “Rh+.” If the D antigen is not present, the person is considered “Rh negative” or “Rh-.”

In contrast to ABO antigens, people do not have naturally occurring antibodies against the Rh factor, but they develop them on exposure. For this reason, a person who is Rh negative develops antibodies against Rh factor only if they are exposed to Rh-positive cells. If this occurs and antibodies develop, subsequent exposure to Rh-positive blood causes a potentially life-threatening immune response with hemolysis of cells.

Rh factor is especially important during maternity care of a mother and her baby. For example, if a mother with Rh-negative blood carries a fetus with Rh-positive blood, her body develops antibodies to the Rh factor. If she becomes pregnant again with a Rh-positive fetus, these antibodies can enter the circulation of the fetus and cause a hemolytic reaction. Therefore, women with Rh-negative blood receive RhoGAM during and after pregnancy to prevent this reaction from occurring in future pregnancies.

See Table 3.2a for an overview of blood types a person can receive based on their ABO blood type and Rh factor.

Table 3.2a Blood Compatibility Based on ABO Blood Type and Rh Factor

| Person’s Blood Type | Types of Blood They Can Receive |

|---|---|

| Type A | Types A and O |

| Type B | Types B and O |

| Type AB | Types A, B, AB, and O |

| Type O | Only Type O |

| Rh+ | Rh+ and Rh- |

| Rh- | Only Rh- |

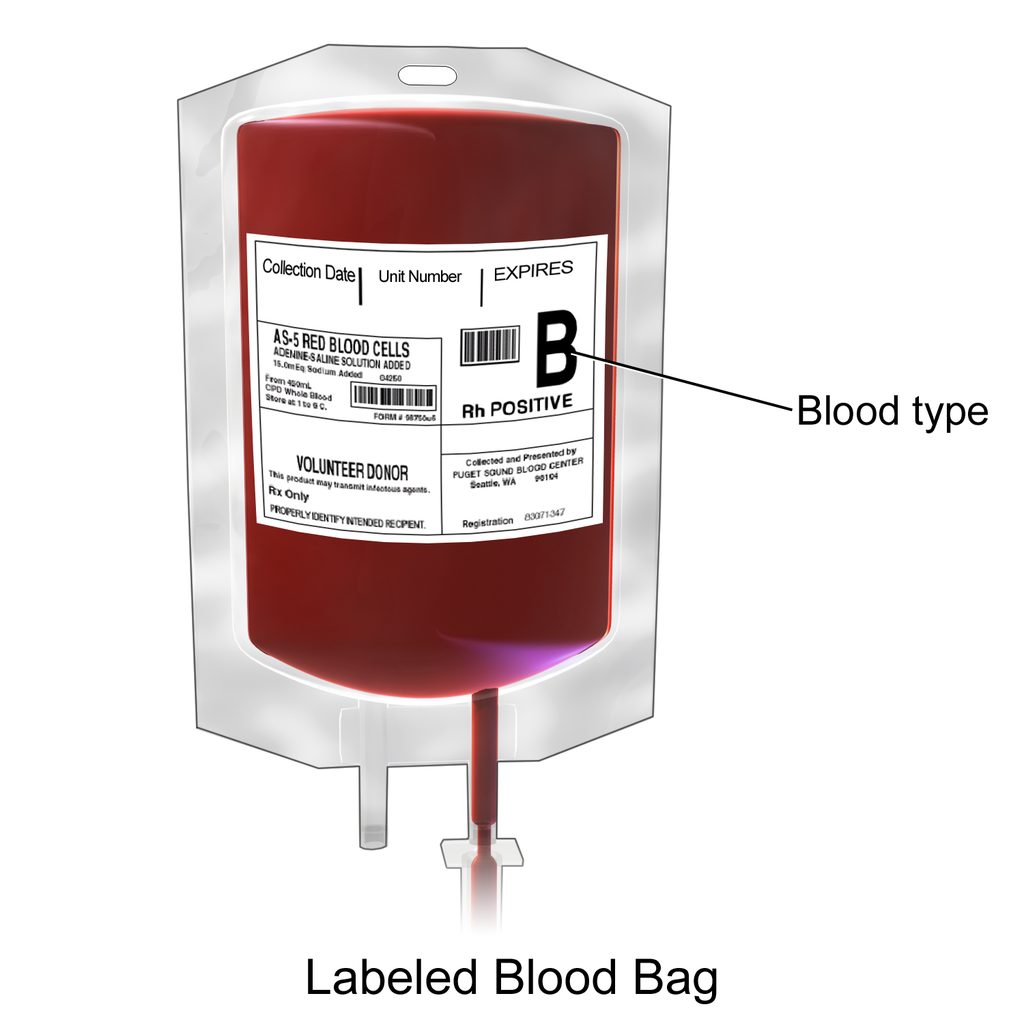

See Figure 3.2[3] for an image of a unit of blood labeled with blood type and Rh factor.

Human Leukocyte Antigen

The human leukocyte antigen (HLA) is an immune-type antigen that can also pose a serious transfusion complication. HLA is located on the surface of leukocytes and may be found on lymphocytes, granulocytes, monocytes, and platelets. HLA contributes to a person’s tissue type and varies among individuals. HLA tests must be completed before any stem cell or organ transplantation is completed to help ensure that the donor and recipient tissues are a match. HLA antigens are a part of an individual’s genetic makeup. Individuals may develop antibodies against HLA antigens following exposure through blood transfusion or pregnancy.

Type and Screen

“Type and screen” refers to pre-transfusion tests that include the determination of client’s ABO group, Rh type, and a screen for the detection of atypical antibodies. Nurses ensure type and screen testing has been completed before initiating a blood transfusion and also use this information during a two-person verification of a blood product before it is administered to a client.

Type and Cross-Match

A “type and cross-match” includes all the steps of a type and screen, but also performs a cross-match test to check the compatibility between the patient’s blood and a specific unit of donor blood. This test is ordered when a transfusion is definitely planned or expected soon. Once complete, the blood bank will reserve compatible blood units for the patient. This ensures safe and timely transfusion, especially in urgent or high-risk situations.

Types of Blood Products

Blood transfusion refers to the intravenous administration of whole blood or blood components into a person’s circulatory system. Blood components include red blood cells (RBC), white blood cells (WBC), platelets, fresh frozen plasma (FFP), clotting factors, cryoprecipitates, and albumin. Whole blood is rarely used in the United States for transfusion because most clients require a specific element of blood, such as red blood cells or platelets, and the required dose can be optimized according to the client’s condition. See Table 3.2b for summarized information about various blood products, including infusion times for adults, ABO/Rh testing requirements, actions, indications, and benefits.[4]

Table 3.2b Blood Products[5],[6]

Used for life-threatening hemorrhage where oxygen-carrying capacity, coagulation factors, platelets, and volume expansion are all needed. Whole blood contains approximately 150 mL of plasma, which provides volume expansion and stabilization of clotting factors.

| Blood Product | Volume/Infusion Time | ABO/Rh Testing Required | Actions/Indications/Benefits |

|---|---|---|---|

| Whole Blood | For massive blood loss, infuse as fast as the client can tolerate. | Yes | Used for life-threatening hemorrhage where oxygen-carrying capacity, coagulation factors, platelets, and volume expansion are all needed. Whole blood contains approximately 150 mL of plasma, which provides volume expansion and stabilization of clotting factors. |

| Red Blood Cells (RBC) | Typical volume of 350 mL must be infused within 4 hours. Commonly infused within 90 minutes to 3 hours. | Yes | Replaces red blood cells and increases oxygen-carrying capacity. Indicated for symptomatic anemia and gastrointestinal bleeding. One unit increases hemoglobin by 1 g/dL and hematocrit (HCT) by 2-3%. |

| Leukocyte-Reduced RBCs (Concentrate of RBCs With White Blood Cells Removed) | Infuse within 4 hours. | Yes | Indicated for symptomatic anemia for patients who are immunocompromised or at risk for reactions caused by leukocyte antibodies to the HLA. It is also recommended for children younger than six years old. It has the same actions/benefits as RBC infusion. |

| Fresh Frozen Plasma (FFP) | Typical volume of 200-250 mL is infused over 60 minutes but must be infused within 4 hours. | Yes | Increases clotting factors and expands blood volume. Indicated for clients with bleeding disorders, thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura (TTP), and life-threatening hemorrhage in patients who have significant coagulation deficiencies. Also used to reverse a client’s elevated INR when it needs to be brought down quickly to prevent complications from occurring. One unit increases clotting factors approximately 2-5%. Plasma is typically frozen within hours of donation to preserve the clotting factors and is thawed by the lab prior to administration. |

| Platelets | Typical volume of 250-350 mL is infused over one hour. | No | Increases the number of platelets to promote hemostasis (i.e., adequate blood clotting). Indicated for thrombocytopenia or platelet function abnormalities, as well as for patients undergoing treatment for leukemia, cancer, aplastic anemia, and marrow transplants. One unit of platelets is created from a pool of 4-6 whole blood donations or from one apheresis (i.e., harvested from one donor with the return of all other cells). One unit increases the platelet level by approximately 30,000-60,000. The bag should be agitated periodically because platelets may adhere to the bag. |

| Cryoprecipitate | Typical volume of 90-120 mL is infused over 15-30 minutes. | Yes | Provides Factor VIII, fibrinogen, vWF, and Factor XIII. Indicated for Hemophilia A, von Willebrand’s disease, and Factor XIII deficiency. Also used as a part of “Mass Transfusion” protocols where clotting factor deficiencies are common. One pool increases fibrinogen approximately 50 mg/dL. |

| Albumin (Colloid-Containing Solution) | Refer to hospital policy. Rate is individualized. | No | Expands blood volume and provides plasma proteins. Indicated for the treatment of severe hypovolemia and/or hypoalbuminemia. Albumin helps hold fluid in the vascular space to temporarily prevent and/or correct third spacing. Used for critically ill patients who have a limited response to crystalloid solutions and those with burns, ascites, and anasarca (i.e., swelling of the whole body from fluid retention). |

| Intravenous Immunoglobulin (IVIG) | Infusion starts at a rate of 0.5 to 1 mL/kg/hour for the first 15-30 minutes and then can be increased every 15-30 minutes to a maximum of 3 to 6 mL/kg/hour if no adverse reactions. | No | Provides antibodies the client cannot make on their own (i.e., “humoral immunodeficiency”). Indicated as replacement therapy for immunodeficiencies, autoimmune conditions such as immune thrombocytopenia (ITP) and autoimmune hemolytic anemia (AIHA), Guillain-Barré syndrome, or chronic inflammatory demyelinating polyneuropathy (CIDP).[7] |

| Autologous | Refer to agency policy for collection and infusion. | No | Provides patient’s own blood to prevent potential transfusion reactions but has risk for bacterial infection. Used to replace blood loss during planned elective surgery. |

Conditions Requiring Blood Product Transfusion

Blood product transfusions can offer life-saving therapeutic benefits for several conditions, such as non-hemorrhagic anemia, active bleeding or symptomatic anemia, loss of coagulation factors, and platelet deficiency or dysfunction.[8]

Non-Hemorrhagic, Asymptomatic Anemia

The current guidelines from the Association for the Advancement of Blood & Biotherapies (AABB) recommend the use of restrictive hemoglobin thresholds to indicate the need for RBC transfusion for anemia, as well as the use of “standard-issue” rather than “fresh” RBCs.[9],[10] Anemia is a hematological condition where there is a lack of healthy red blood cells and/or hemoglobin to carry adequate oxygen to the body’s tissues.

- Recommendation 1:

- A threshold of hemoglobin level of 7 g/dL or less is recommended for the indication of RBC transfusion for hospitalized adult patients with asymptomatic anemia who are hemodynamically stable, including critically ill patients.

- A threshold of 8 g/dL or less is recommended for RBC transfusion for patients undergoing orthopedic surgery, cardiac surgery, and those with preexisting cardiovascular disease.

- Recommendation 2:

- Patients, including neonates, should receive “standard issue” RBCs (i.e., units selected at any point within their licensed dating period) rather than limiting patients to transfusion of only “fresh” RBCs (i.e., units with storage length less than ten days).

Active Bleeding and Symptomatic Anemia

RBC transfusions are indicated for patients who are actively bleeding or for those with symptomatic anemia whose hemoglobin is less than 8 g/dL. Symptoms of anemia include, but are not limited to, weakness, dyspnea with exertion, and tachycardia. Each case is individually evaluated to compare the patient’s need for transfusion with its risks and benefits. Unless the patient is actively bleeding, it is recommended to transfuse one unit of packed red cells at a time, which typically increases the patient’s hemoglobin level by 1 g/dL and their hematocrit by 3%. Hemoglobin levels should be checked 4-24 hours post-transfusion or according to agency policy.[11]

Loss of Coagulation Factors

Transfusion of fresh frozen plasma (FFP) is commonly used for prophylaxis in non-bleeding patients. It is also indicated for acutely bleeding patients to replace their lost coagulation factors. Other clinical situations that may indicate coagulation factor replacement include cardiopulmonary bypass, massive transfusion, decompensated liver disease, extracorporeal pulmonary support techniques, acute disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC), and prior to invasive procedures for patients with decreased clotting factors and/or elevated INR.[12]

Platelet Deficiency/Dysfunction

Platelet transfusions are an effective treatment for patients with platelet deficiency and/or platelet dysfunction, such as bone marrow insufficiency or thrombocytopenia. Platelet transfusions for patients who are thrombocytopenic may be done prophylactically to either prevent or reduce the severity of spontaneous patient bleeding with platelet counts less than 10,000/uL and no other risk factors are present for bleeding. If a client is actively hemorrhaging and thrombocytopenia is contributing to the hemorrhaging, platelets should be infused if the platelet count is less than 50,000/uL.[13]

There are different types of platelet infusions, and they yield different results. A typical unit of apheresis platelets should increase the recipient’s platelet count by 30,000 to 60,000/uL. Apheresis is a procedure in which whole blood is collected from a donor, part of the blood such as platelets or white blood cells is removed, and the rest of the blood is returned to the donor. In comparison to apheresis platelets, whole-blood derived platelets, which are often pooled from several donors, are expected to raise the platelet count by 5,000 to 10,000/uL.[14]

Fibrinogen Deficiency or Disorders

Cryoprecipitate transfusion is indicated in dysfibrinogenemia or fibrinogen deficiency (hypofibrinogenemia) when the patient is experiencing active bleeding, traumatic injury, invasive procedures, or acute disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC).[15] Dysfibrinogenemia is a coagulation (clotting) disorder characterized by an abnormal form of fibrinogen. Hypofibrinogenemia is a rare, autosomal dominant condition characterized by bleeding and obstetric problems such as abruption, postpartum hemorrhage, and recurrent pregnancy loss. Fibrinogen is a protein produced by the liver that helps control bleeding by helping blood clots to form; abnormal or deficient fibrinogen results in defective clot formation.

Severe Hypovolemia

Rapid infusion of crystalloid solutions, such as 0.9% normal saline, remains the standard, evidence-based first-line treatment for severe hypovolemia or hypovolemic shock due to their wide availability, low cost, and effectiveness in restoring intravascular volume. Crystalloids primarily expand extracellular fluid and require larger volumes to achieve hemodynamic stability.

However, when patients show a limited response to crystalloids or when hypoalbuminemia is suspected to contribute to fluid imbalance, colloid solutions like albumin may be considered. Albumin is the primary protein responsible for maintaining plasma oncotic pressure, and it plays a crucial role in modulating fluid distribution between body compartments. It treats hypovolemia by drawing sodium and water into the intravascular space, thereby increasing circulating volume more efficiently than crystalloids in some cases.

While albumin can be effective, its use should be carefully evaluated due to higher cost, limited availability, and potential risks, including allergic reactions and fluid overload in certain patients.[16],[17]

Transfusion Reactions

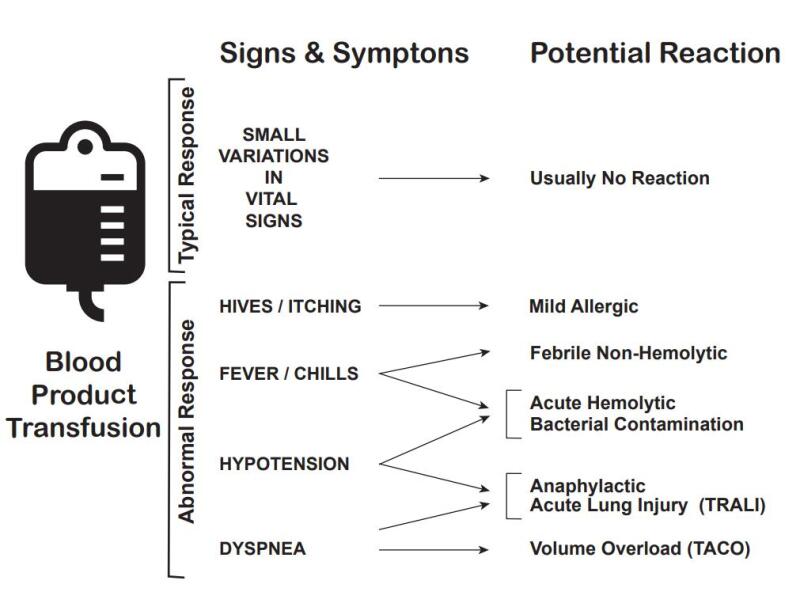

Transfusion reactions are adverse events that are directly related to the transfusion of blood products and may range from mild to severe with life-threatening effects. The onset of transfusion reactions may occur during the transfusion (known as acute transfusion reactions) or in days or weeks following the transfusion (known as delayed transfusion reactions). Reactions may be an immune-related reaction or non-immunological condition. Immune-related reactions are often due to a mismatch or incompatibility of the transfused blood product and the recipient’s blood type or Rh factor. Non-immunologic reactions are typically caused by the physical effects of the blood component or the transmission of a disease.

It can be difficult to ascertain if a reaction will occur and what kind of reaction is occurring because some reactions can present with non-specific, overlapping manifestations. The most common manifestations of transfusion reactions include fever, urticaria, chills, and itching. Some mild symptoms may resolve without treatment, but some are severe, presenting with high fevers, respiratory distress, hypotension, and hemoglobinuria.[18]

The most common types of transfusion reactions include acute hemolytic, febrile non-hemolytic, delayed hemolytic, anaphylactic, simple allergic, transfusion-associated circulatory overload (TACO), transfusion-related acute lung injury (TRALI), and septic (bacterial contamination).[19] If a patient experiences a blood transfusion reaction, always follow agency policy to manage mild to severe blood reactions. See Table 3.2c for additional information about different types of transfusion reactions, their causes, onset, manifestations, prevention, and related nursing interventions.[20] See Figure 3.3 for an illustration of common manifestations of transfusion reactions.

![]() Life-threatening transfusion reactions typically occur within 15 minutes of initiating a transfusion. Remain with the patient during this time and monitor their physiologic responses.

Life-threatening transfusion reactions typically occur within 15 minutes of initiating a transfusion. Remain with the patient during this time and monitor their physiologic responses.

Table 3.2c Transfusion Reactions and Related Nursing Interventions[21]

| Transfusion Reaction | Cause | Onset | Manifestations | Prevention | Nursing Interventions |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mild to Moderate Allergic Reaction | Hypersensitivity to a foreign protein in the donor product. | During the transfusion and up to 24 hours post-transfusion. | Pruritus, erythema, urticaria, and bronchospasm. | If known history of a previous allergic reaction, may require administration of an antihistamine prior to infusion. | Stop transfusion and notify the provider. Administer antihistamine if prescribed and carefully monitor for new or progression of symptoms. Analyze vital signs every 15 minutes. |

| Anaphylactic | Recipient allergy to donor antigen (most often IgA). | Occurs within 5-15 minutes of initiation of transfusion. | Similar to mild/moderate allergic reaction, but more severe with nausea/vomiting, shortness of breath, cough, wheezing, hypotension, and loss of consciousness. May lead to cardiac arrest. | If known history of previous allergic reaction, transfuse with leukocyte – depleted RBCs. | Stop transfusion and notify the provider. Maintain IV access. Administer epinephrine, antihistamines, and corticosteroids as prescribed. Monitor vital signs frequently until stable. |

| Febrile Non-Hemolytic | Caused by cytokines released from blood donor’s leukocytes or platelets. Most common transfusion reaction that typically occurs in immunocompromised patients. | Occurs 30 minutes after initiation of transfusion to 6 hours post-transfusion. | Increased fever greater than 1 degree Celsius above baseline with associated flushing, chills, muscle pain, and headache. Tachycardia, tachypnea, and hypotension may also occur. | If known history of a previous febrile non-hemolytic reaction, use a leukocyte-reduced blood product. | Stop transfusion and notify the provider. If prescribed, administer antipyretics. Monitor temperature every four hours and as needed. |

| Acute Hemolytic | ABO and Rh incompatibility results in destruction of RBCs. | Occurs within 15 minutes of initiation of transfusion. | Flank pain, chest pain, increased heart rate, chills, increased temperature, low back pain, headache, dyspnea, bronchospasm, anxiety, hypotension, or pain along the accessed vein. | Considered a hospital-acquired condition preventable by diligent patient identification and blood product compatibility verification. | Stop transfusion, remove blood tubing, and maintain access with 0.9% normal saline. Notify the provider and monitor vitals every 15 minutes. Obtain blood and urine samples and send to the lab with unused portion of blood product. |

| Septic | Contamination of blood product with bacterial microorganisms. | During transfusion and possibly up to two hours post-transfusion. | High fever, skin flushing, hypotension, back pain, abdominal cramping, nausea, and vomiting and diarrhea. | Complete transfusion within four hours to avoid bacterial growth. Proper care of blood product is required from donation through administration. | Stop the transfusion, remove blood product and tubing, and maintain IV access with 0.9% normal saline. Notify the provider. Monitor vital signs. Obtain blood cultures as prescribed. Administer fluids, obtain gram stain, and provide broad-spectrum antimicrobials as prescribed. |

| Transfusion-Associated Circulatory Overload (TACO) | Occurs when the volume of the transfusing blood component causes volume overload (hypervolemia) from an overly rapid administration rate or amount. | Can occur anytime during the transfusion or within 1-2 hours post-transfusion. | Crackles in lung bases, dyspnea, cough, tachypnea, tachycardia, hypertension, jugular vein distension, and headache. | Follow prescribed rate of infusion, typically 2 – 4 mL/kg/hr. Use caution with older adults and with those who have cardiac and renal disorders. | Reduce rate or stop transfusion as prescribed by provider. Monitor and manage patient manifestations. Elevate head of bed and administer diuretic as prescribed. |

| Transfusion – Related Acute Lung Injury (TRALI)[22] | Acute lung injury caused by antibodies in the donor blood products that react with antigens in the recipient. Recipient chemical mediators are released and lead to pulmonary edema. | Within 6 hours to 72 hours of transfusion of blood products that are rich in plasma. | Cyanosis, dyspnea, fever, hypoxemia, hypotension, and pulmonary edema that is not cardiac-related (i.e., due to fluid overload). | Assess for contributing factors that predispose the patient to this condition, including infection, inflammation, or recent surgery. | Stop the transfusion immediately and notify the provider. Administer treatment to support blood pressure as prescribed. Administer supplemental oxygen as prescribed. Prepare for endotracheal intubation and mechanical ventilation. Notify the blood bank so they can screen for certain donor antibodies. |

For more information, review the article “Transfusion Reactions.”[23]

View this supplementary YouTube video[24] on blood transfusion reaction types.

Initiating Blood Product Therapy

Nurses and health care practitioners who administer blood products must complete specific training for safe transfusion practices and demonstrate competency in the transfusion administration process. Always refer to agency policy for guidelines for preparing, initiating, and monitoring blood product transfusions. The nurse is responsible for knowing which blood components are appropriate for specific client situations and serving as the last link in the chain of safety events.

Agency policy and procedures must be strictly followed to prevent client harm. The nurse must verify that the client has signed informed consent for the procedure in their medical record. Prior to blood product administration, the nurse confirms that a blood sample has been collected from the client and transported to the laboratory within the past 72 hours for typing and compatibility screening. This is the first step in maintaining patient safety and preventing errors.

Diligent patient identification and blood product compatibility verification are vital for safe blood product administration. A two-person verification process is used for blood product transfusions. The first individual is the qualified transfusionist who will administer the blood or blood product to the client. The second individual conducting the identification verification process is qualified to participate in the verification process, as determined by the hospital.

Blood is stored within a refrigerated area. Blood products should never be heated in a microwave or hot water or vigorously shaken because this will destroy the blood cells. In certain circumstances, such as trauma or surgery, blood may be warmed with an appropriate blood warmer, but this is prescribed within designated conditions and not a routine practice.

Health Care Team Collaboration

Blood product transfusion therapy is implemented by several members of the health care team. Nurses must be knowledgeable of the transfusion process, potential complications, and management of possible complications. The majority of transfusion reactions occur because of clinical error. Engaging in interprofessional teamwork, utilizing effective communication, and adhering to evidence-based protocols improve patient outcomes and safety. If there are any concerns during any step in the blood product administration process, the nurse must advocate for patient safety.[25]

Blood product transfusion therapy cannot be delegated to unlicensed assistive personnel (UAP). However, if the client is stable, UAP may obtain vital signs as instructed during the transfusion and report any concerns or complaints to the supervising nurse.

Cultural Considerations

When administering blood products, be aware of the client’s beliefs (and in the case of minors, their parents’ religious beliefs). Some religions, such as Jehovah’s Witnesses, oppose blood transfusions. They may be excommunicated from their church and the facility can be sued, even if the transfusion is implemented to save their life. This is another reason why it is critical to obtain written informed consent prior to initiating blood or blood product administration. It is essential to follow agency policies and procedures if a client (or the parent of a minor) refuses blood therapy.[26]

Autologous Blood Transfusion

Autologous blood transfusion is a procedure in which blood is removed from the client and returned to their circulation at a later time, instead of relying on blood donated by others (referred to allogeneic blood). Autologous blood transfusion can be performed in different ways, such as elective preoperative blood collection and retransfusion of blood during surgery or intraoperative hemodilution.

Autologous blood transfusion avoids the risks of transfusion reactions that can occur with allogeneic blood. It may also be acceptable for clients prior to stem cell transplantation, clients with leukemias or lymphomas, or clients with religious beliefs who oppose blood transfusions.

- Derivative of “a9fa9181b953f0a6a9596420b0f714ad4a497b16” by unknown author is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/anatomy-and-physiology-2e/pages/18-6-blood-typing ↵

- Bediako, A. A., Ofosu-Poku, R., & Druye, A. A. (2021). Safe blood transfusion practices among nurses in a major referral center in Ghana. Advances in Hematology, 2021. https://www.hindawi.com/journals/ah/2021/6739329/ ↵

- “Blausen_0086_Blood_Bag.png” by Blausen.com staff (2014) at “Medical gallery of Blausen Medical 2014.” WikiJournal of Medicine is licensed under CC BY 3.0 ↵

- Association for the Advancement of Blood & Biotherapies. (n.d.). Regulatory for blood and blood components. https://www.aabb.org/regulatory-and-advocacy/regulatory-affairs/regulatory-for-blood ↵

- Association for the Advancement of Blood & Biotherapies. (n.d.). Regulatory for blood and blood components. https://www.aabb.org/regulatory-and-advocacy/regulatory-affairs/regulatory-for-blood ↵

- Bloodworks Northwest. (n.d.) Transfusion medicine: Typical rates, volumes, and durations for routine (non-emergent) transfusions. https://www.bloodworksnw.org/medical-services/transfusion-medicine/rates-volumes-duration-transfusions ↵

- Shehata, N. (2023). Patient education: Intravenous immune globulin (IVIG) (Beyond the basics). UpToDate. www.uptodate.com ↵

- Bediako, A. A., Ofosu-Poku, R., & Druye, A. A. (2021). Safe blood transfusion practices among nurses in a major referral center in Ghana. Advances in Hematology, 2021. https://www.hindawi.com/journals/ah/2021/6739329/ ↵

- Association for the Advancement of Blood & Biotherapies. (n.d.). Regulatory for blood and blood components. https://www.aabb.org/regulatory-and-advocacy/regulatory-affairs/regulatory-for-blood ↵

- Carson, J. L., Guyatt, G., Heddle, N. M., Grossman, B. J., Cohn, C. S., Fung, M. K., Gernsheimer, T., Holcomb, J. B., Kaplan, L. J., Katz, L. M., Peterson, N., Ramsey, G., Rao, S. V., Roback, J. D., Shander, A., & Tobian, A. A. (2016). Clinical practice guidelines from the AABB: Red blood cell transfusion thresholds and storage. JAMA, 316(19), 2025–2035. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2016.9185 ↵

- This work is a derivative of StatPearls by Lotterman & Sharma and is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- This work is a derivative of StatPearls by Lotterman & Sharma and is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- This work is a derivative of StatPearls by Lotterman & Sharma and is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- This work is a derivative of StatPearls by Lotterman & Sharma and is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- This work is a derivative of StatPearls by Lotterman & Sharma and is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- Caraceni, P., Tufoni, M., & Bonavita, M. E. (2013). Clinical use of albumin. Blood Transfusion = Trasfusione del Sangue, 11(Suppl 4), s18–s25. https://doi.org/10.2450/2013.005s ↵

- Mandel, J., & Palevsky, P. M. (2022). Treatment of severe hypovolemia or hypovolemic shock in adults. UpToDate. https://www.uptodate.com ↵

- This work is a derivative of StatPearls by Lotterman & Sharma and is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- This work is a derivative of StatPearls by Lotterman & Sharma and is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- This work is a derivative of StatPearls by Lotterman & Sharma and is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- This work is a derivative of StatPearls by Lotterman & Sharma and is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- This work is a derivative of StatPearls by Cho, Modi & Sharma and is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- This work is a derivative of StatPearls by Suddock and Crookston and is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- RegisteredNurseRN. (2018, March 20). Blood transfusion procedure nursing | Reaction types, complications (hemolytic/ febrile) NCLEX [Video]. YouTube. Used with permission. https://youtu.be/v4PHCwvkH24 ↵

- This work is a derivative of StatPearls by Suddock & Crookston and is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- Sagy, I., Jotkowitz, A., & Barski, L. (2017). Reflections on cultural preferences and internal medicine: The case of Jehovah's Witnesses and the changing thresholds for blood transfusions. Journal of Religion and Health, 56(2), 732–738. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10943-016-0353-1 ↵

Red blood cell destruction.

A hematological condition where there is a lack of healthy red blood cells and/or hemoglobin to carry adequate oxygen to the body's tissues.

Platelet deficiency causing bleeding, bruising, and slow blood clotting after injury.

A coagulation (clotting) disorder characterized by abnormal fibrinogen.

A rare, autosomal dominant condition characterized by bleeding and obstetric problems such as abruption, postpartum hemorrhage, and recurrent pregnancy loss.

Adverse events that are directly related to the transfusion of blood products and may range from mild to severe with life-threatening effects.

A procedure in which blood is removed from the patient and returned to their circulation at a later time, instead of relying on blood donated by others (referred to allogeneic blood).

Blood products donated by other people.