1.3 Peripheral IV Access

The initiation and maintenance of a peripheral venous access includes selecting an appropriate site, selecting an appropriate IV catheter and size, establishing IV access, and monitoring for potential complications. The nurse also incorporates life span considerations while following general guidelines for maintaining peripheral venous access sites.

Selection of Venous Access Site Selection

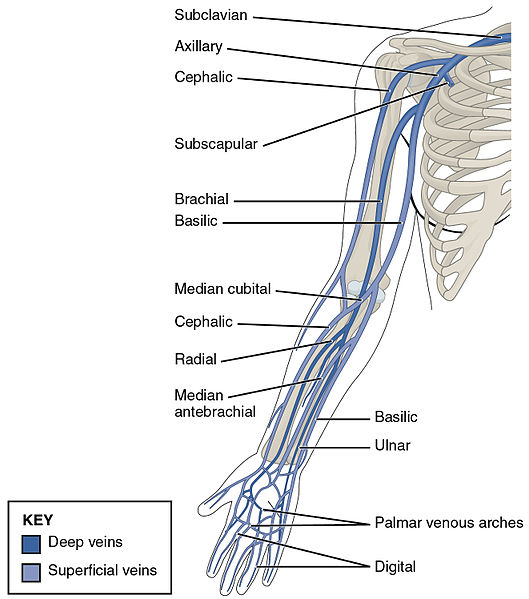

The process of IV start and vessel cannulation includes a comprehensive vein search, identification, and assessment process. Veins in the upper extremities (hands and arms) are typically the preferred sites for insertion. The nurse should be systematic when assessing potential vessels for insertion, examining potential sites both visually and through palpation while progressing up the patient’s extremity. The arms should be rotated so that vessels on the dorsal surface can be considered as well. Taking time to identify the best access site will increase the chances for successful cannulation and decrease discomfort for the patient. See Figure 1.12[1] for an illustration of vein anatomy in the upper extremity.

The veins of the hands are common places to begin one’s assessment. These veins on the dorsal surface of the hand are typically easily visualized and palpated due to the proximity to the surface of the skin. See Figure 1.13[2] for an image of the veins in a hand. Veins on the palmar side of the wrist should be avoided due to potential nerve damage. A limitation of using hand veins for venous access is they are smaller than the cephalic, basilic, or brachial veins in the arm. For example, if the patient requires rapid infusion of fluid or administration of blood products, a large gauge IV cannula is typically placed in a large vein in the upper arm.

If no suitable veins are found on the hand, the nurse should progress up the arm and continue to assess for good access sites. The basilic and cephalic veins are good alternatives for establishing IV access. The brachial vein can be considered, but caution must be used due to its location near the brachial artery in the antecubital fossa. Palpating for a pulse and then avoiding the area where the pulse is located can help ensure cannulation occurs into a vein rather than the artery.[3]

Nurses must also reflect on the purpose for venous access to determine the appropriate access site and catheter lumen size. For example, consider the venous access site required to obtain a blood sample specimen versus that to provide intravenous fluid administration. For blood sampling, the nurse should direct attention to the large veins located in the antecubital fossa (i.e., the interior aspect of the elbow) because the veins are larger in size and can be accessed frequently. However, these veins are not optimal for routine IV fluid administration because every time the patient bends their elbow, a mechanical obstruction in the IV catheter may occur. Despite the potential disadvantage of mechanical obstruction when accessing veins in the antecubital fossa, the nurse may still decide to access veins in the antecubital fossa if rapid IV access is needed or if the patient is only receiving intermittent short-term infusions. In this manner, the purpose for a patient’s venous access plays a strong role in determining the appropriate access site.

When considering a potential site for IV cannulation, it is important to note that a catheter must be inserted and threaded for a short distance into the vein. Veins that have ¼- to ½-inch sections of straight surface are usually easily accessed. Suitable IV access sites include lengths of veins that feel spongy and resilient to the touch. Veins that bifurcate (i.e., divide into branches), narrow significantly, or are curved can be difficult to access and thread the cannula. Nurses should also palpate for knobby bumps in a vein that may indicate the presence of valves in that area. Valves can be difficult to cannulate through and, therefore, should be avoided.

If a patient has several suitable venous access sites, preference should be given to establishing an access site on their nondominant hand or arm. Patients typically use their dominant hand when moving to reposition themselves, take meals or fluids, or operate the television remote. These movements can increase the chance of the cannula dislodging from the vein.[4]

Additional considerations for vein selection include avoiding extremities with restrictions such as those with a previous history of mastectomy, lymph node dissection, or arteriovenous (A/V) fistula; the presence of a cast or other assistive device; or those with conditions causing reduced sensation or movement such as paralysis or stroke. The presence of an IV cannula in extremities with these conditions increases the risk for localized infection and other complications.

The nurse should also consider the condition of the patient’s skin when selecting an access site. Skin that is scarred can be fibrous and tough to penetrate with a needle, causing increased discomfort. Sites below a recent venipuncture or IV access site should also be avoided due the potential for fluids to seep out of the site. Additionally, skin that is tattooed or extremities with edema should also be avoided whenever possible. Tattoos and edema make a vein not only more difficult to identify, but also more difficult to assess for signs of complications such as cannula dislodgement and the presence of fluid leaking into subcutaneous tissues.

There are many methods that nurses can use to dilate veins and determine the presence of suitable access sites if the veins are not visually apparent. A simple method is to apply a single-use tourniquet. The tourniquet should be snug but still allow for the presence of arterial blood flow. Blood flow can be easily assessed by applying the tourniquet and assessing the presence of the radial pulse. Tourniquets should only be applied for short periods of time and released periodically during the vein search and selection process to ensure resolution of systemic blood flow. In a similar manner, a blood pressure cuff can be also applied and pumped up for a short period of time.

Application of warmth can also be helpful for vein identification. Wrapping the upper extremities in warm blankets, or applying warm compresses, promotes vessel dilation. The blankets or compresses should be in place for short intervals (i.e., 3-5 minutes) to allow time for the vessels to respond to the warm stimuli.

Placing the upper extremities in a dependent position is another useful method for enhancing vessel dilation. Allowing the arm and hand to hang dependently (i.e., below the level of the heart) allows venous blood to migrate by gravity into the lower arms and hands. The pooling of venous blood into the small vessels of the hands promotes vessel dilation and vein identification.

In addition to promoting vessel dilation, nurses may also be trained in some facilities to use equipment to visually detect veins, such as illumination lights or ultrasound equipment. Some agencies also have specially trained venous access teams who insert intravenous lines and can be consulted if vascular access proves challenging.

Many patients have had previous experience with IVs and can provide helpful information regarding strategies for success. For example, if a patient states, “My veins often ‘roll’ when they try to start an IV,” the nurse should take special caution to anchor the vessel when puncturing the skin.

Nurses should restrict IV insertion attempts to no more than two attempts per clinician. Multiple unsuccessful attempts cause pain to the client, delay treatment, limit future vascular access, increase cost, increase the risk for complications, and decrease trust in the nurse. After two unsuccessful attempts, the nurse should seek a clinician with a higher skill level or consider alternative routes of medication administration.[5]

Catheter Size and Type Selection

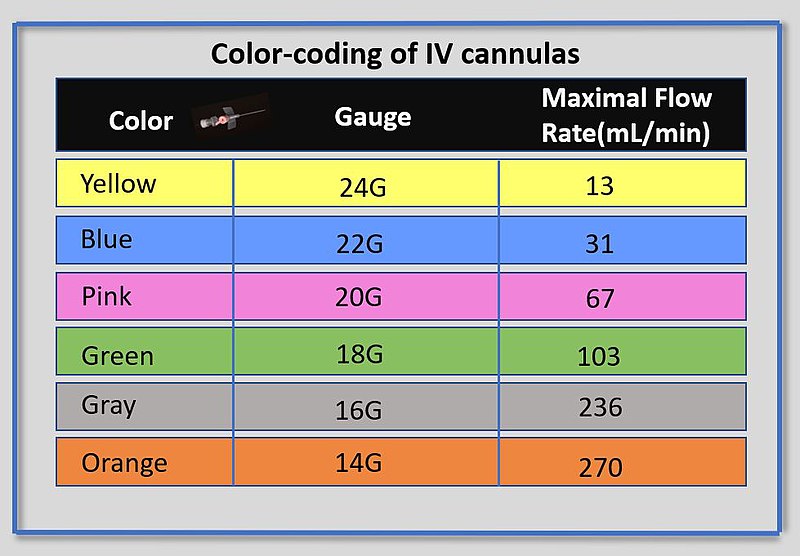

Peripheral IV catheters are available in a variety of sizes, most commonly ranging from 14 gauge to 24 gauge. Note that the lower the gauge size, the wider the diameter of the catheter, with 14-gauge catheters allowing for the greatest flow rate.[6] Catheter sizes are color coded to allow for easy identification of the catheter size after a vein is accessed. See Figure 1.14[7] for colors associated with IV catheter sizes and their associated flow rates.

Nurses must consider the purpose for venous access, along with assessment of the client’s vessel size, when selecting an IV catheter to attempt cannulation. Catheters with a smaller gauge (i.e., larger diameter) permit infusion of viscous fluids, such as blood products, at a faster rate with decreased opportunity for catheter occlusion.[8] Additionally, an appropriately sized catheter also allows for adequate blood flow around the catheter itself. The most common IV catheter size for adult patients is 18- or 20-gauge catheters. However, frail elderly patients and children have smaller vasculature, so a 22-gauge catheter is often preferred.

There are different manufacturer brands of IV catheters, but all include a beveled hollow needle, flashback chamber in which one can visualize blood return when entering the vein, and a flexible catheter that is left in the vein after the catheter has been threaded into the vein and the needle removed.

IV insertion equipment varies among institutions, but common types include shielded IV catheters or winged (i.e., “butterfly”) devices. Variation is often related to the presence of a stabilizing device at the site of insertion, as well as the presence of short extension tubing. For shielded catheter types, the stabilizing device and extension tubing are typically added to the catheter itself and not included with the cannulation needle. See Figure 1.15[9] for an image of shielded IV catheters.

Nurses must ensure the selected size and type of IV catheter are appropriate for the procedure or infusion that is ordered because not all peripheral IV catheters are suitable for all procedures. For example, if a procedure requires the infusion of contrast dye, a specific size infusion port is required.

Despite the wide variation in catheter equipment that is available, there has been significant focus among manufacturers regarding the need for safety equipment during venipuncture. Many devices utilize mechanisms to self-contain needles within a plastic sheath after withdrawal from the client. These devices can be activated through a button in the devices or a manual trigger initiated by the individual attempting cannulation. Regardless of the type of safety lock, it is important to utilize the equipment as intended and never attempt to disable or override the mechanism. These mechanisms are important to help prevent accidental needlesticks or injury with a contaminated needle after it has been removed from the patient. Additionally, after cannulation is attempted, the individual who attempted cannulation is responsible for ensuring all needles are disposed of in a sharps container. It is good practice to be aware of how many sharps were brought into the room, opened, and disposed. This helps to ensure that any needles are not inadvertently left in a patient’s bed, tray table, floor, etc. Nurses must be familiar with the equipment used at the health care facility and receive orientation on the specific mechanics related to the equipment and safety practices.

Initiating Peripheral IV Access

The steps for initiating peripheral IV access are described in the “Perform IV Insertion and IV Removal” checklist later in this chapter.

Monitoring for Potential Complications

Several potential complications may arise from peripheral intravenous therapy. It is the responsibility of the nurse to monitor for signs and symptoms of complications and intervene appropriately. Complications can be categorized as local or systemic. See Table 1.3a for potential local complications of peripheral IV therapy.

Table 1.3a Local Complications of Peripheral IV Therapy[10],[11]

| Complications | Potential Causes and Prevention | Treatment |

|---|---|---|

| Phlebitis: The inflammation of the vein’s inner lining, the tunica intima. Clinical indications are localized redness, pain, heat, purulent drainage, and swelling that can track up the vein leading to a palpable venous cord. | Chemical causes: Inflammation of the vein’s inner lining can be caused by medications or fluids with high alkaline, acidic, or hypertonic qualities. To avoid chemical phlebitis, follow the parenteral drug therapy guidelines in a drug reference resource for administering IV medications, including the appropriate amount of solution and rate of infusion.

Mechanical causes: Inflammation of the vein’s inner lining can be caused by the cannula rubbing and irritating the vein. To prevent mechanical inflammation, use the smallest gauge possible to deliver the medication or required fluids. Avoid inserting over areas of flexion.

Infectious causes: May be related to emergent VAD insertions, poor aseptic technique, or contaminated dressings. |

Chemical phlebitis: Evaluate infusion therapy and the need for different vascular access, different medication, slower rate of infusion, or more dilute infusate. If indicated, remove the Vascular Access Device (VAD).[12]

Transient mechanical phlebitis: May be treatable by stabilizing the catheter, applying heat, elevating limb, and providing analgesics as needed. Consider requesting other pharmacologic interventions such as anti-inflammatory agents if needed. Monitor site for 24 hours post-insertion, and if signs and symptoms persist, remove the catheter.[13] Infectious phlebitis: If purulent drainage is present or infection is suspected, remove the catheter and obtain a culture of the purulent drainage and catheter tip. Monitor for signs of systemic infection.[14] |

| Infiltration: A condition that occurs when a nonvesicant solution is inadvertently administered into surrounding tissue. Signs and symptoms include pain, swelling, redness, the skin surrounding the insertion site is cool to touch, there is a change in the quality or flow of IV, the skin is tight around the IV site, IV fluid is leaking from IV site, or there are frequent alarms on the IV pump. | Infiltration is one of the most common complications in infusion therapy involving an IV catheter.[15] For this reason, the patency of an IV site must always be checked before administering IV push medications.

Infiltration can be caused by piercing the vein, excessive patient movement, a dislodged or incorrectly placed IV catheter, or too rapid infusion of fluids or medications into a fragile vein. Always secure a peripheral IV catheter with tape or a stabilization device to avoid accidental dislodgement. Avoid sites that are areas of flexion. |

Stop the infusion and remove the cannula. Follow agency policy related to infiltration. |

| Extravasation: A condition that occurs when vesicant (an irritating solution or medication) is administered and inadvertently leaks into surrounding tissue and causes damage. It is characterized by the same signs and symptoms as infiltration but also includes burning, stinging, redness, blistering, or necrosis of the tissue. | Extravasation has the same potential causes as infiltration but with worse consequences because of the effects of vesicants. Extravasation can result in severe tissue injury and necrosis. For this reason, known vesicant medications should be administered via central lines. | Stop the infusion. Detach all administration sets and aspirate from the catheter hub prior to removing the catheter to remove vesicant medication from the catheter lumen and as much as possible from the subcutaneous tissue.[16]

Follow agency policy regarding extravasation of specific medications. For example, toxic medications have a specific treatment plan. |

| Hemorrhage: Bleeding from the IV access site. | Bleeding occurs when the IV catheter becomes dislodged. | If dislodgement occurs, apply pressure with gauze to the site until the bleeding stops and then apply a sterile transparent dressing. |

| Local infection: Infection at the site is indicated by purulent drainage, typically two to three days after an IV site is started. | Local infection is often caused by nonadherence to aseptic technique during IV initiation or IV maintenance or the dressing becomes contaminated or non-intact over the access site. | Remove the cannula and clean the site using sterile technique. If infection is suspected, remove the catheter and obtain a culture of the purulent drainage and catheter tip. Monitor for signs and symptoms of systemic infection. |

| Nerve injury[17] | Paresthesia-type pain occurring during venipuncture or during an indwelling IV catheter can indicate nerve injury. | Immediately remove the cannula, notify the provider, and document findings in the chart. |

In addition to local complications that can occur at the site of IV insertion, there are many systemic complications that nurses must monitor for when initiating peripheral IV access, as well as monitoring a client receiving IV therapy. See Table 1.3b for a list of systemic complications, signs, symptoms, and treatment.

Table 1.3b Systemic Complications of Peripheral IV Therapy[18]

| Complication | Signs, Symptoms, and Treatment |

|---|---|

| Pulmonary Edema | Pulmonary edema, also known as fluid overload or circulatory overload, is a condition caused by excess fluid accumulation in the lungs due to excessive fluid in the circulatory system. It is characterized by decreased oxygen saturation; increased respiratory rate; fine or coarse crackles in the lung bases; restlessness; breathlessness; dyspnea; and coughing up pink, frothy sputum. Pulmonary edema requires prompt medical attention and treatment. If pulmonary edema is suspected, raise the head of the bed, apply oxygen, take vital signs, complete a cardiovascular assessment, and immediately notify the provider. |

| Air Embolism | Air embolism refers to the presence of air in the cardiovascular system. It occurs when air is introduced into the venous system and travels to the right ventricle and/or pulmonary circulation. Air embolisms can occur during catheter insertion, changing IV bags, adding secondary medication administration sets, and catheter removal. Inadvertent administration of 10 mL of air can have serious and fatal consequences. However, small air bubbles are tolerated by most patients. Signs and symptoms of an air embolism include sudden shortness of breath, continued coughing, breathlessness, shoulder, neck, or chest pain, agitation, feeling of impending doom, light-headedness, hypotension, wheezing, increased heart rate, altered mental status, and jugular venous distension.

If an air embolism is suspected, occlude the source of air entry. Place the patient in a Trendelenburg position on their left side (if not contraindicated), apply oxygen at 100%, obtain vital signs, and immediately notify the provider. To prevent air embolisms, perform the following steps when administering IV therapy: ensure the drip chamber is one-third to one-half filled, remove all air from the IV tubing by priming it prior to attaching it to the client, use precautions when changing IV bags or adding secondary medication bags, ensure all IV connections are tight, and ensure clamps are used when the IV system is not in use. |

| Catheter Embolism | A catheter embolism occurs when a small part of the cannula breaks off and flows into the vascular system. When removing a peripheral IV cannula, inspect the catheter tip to ensure the end is intact. Notify the provider immediately if the catheter tip is not intact when it is removed. |

| Catheter-Related Bloodstream Infection (CRBSI) | Catheter-related bloodstream infection (CRBSI) is caused by microorganisms introduced into the bloodstream through the puncture site, the hub, or contaminated IV tubing or IV solution, leading to bacteremia or sepsis. A CRBSI is a hospital-acquired preventable infection and considered an adverse event. A CRBSI is diagnosed when infection occurs with one positive blood culture in a patient with a vascular device (or a patient who had a vascular device within 48 hours before the infection) with no apparent source for the infection other than the vascular access device. Treatment for CRBSI is IV antibiotic therapy.

To prevent CR-BSI, it is vital to perform hand hygiene prior to care and maintenance of an IV system and to use strict aseptic technique for care and maintenance of all IV therapy procedures. |

Life Span Considerations

IV initiation procedures vary significantly for pediatric patients and older adults due to patient size and variation in vessel size and condition. For example, in neonatal patients, venous access may be achieved through cannulation of a vein in their hand, foot, or scalp. However, IV initiation into a scalp vessel requires specific modifications and additional training. Additionally, use of a lower extremity for venous access should be specifically addressed with the provider prior to any attempt at cannulation to ensure that a lower extremity site is appropriate based on the patient condition.

When working with pediatric patients, it is important to consider the stability of the IV access. Many pediatric patients are very mobile and may not be able to understand the need to leave a saline lock or continuous infusion line in place. Utilizing stabilizing arm boards or gauze wraps may be helpful reminders that also create stability in the line and access site. Many health care organizations have additional tools and strategies to ease IV cannulation for pediatric patients, such as topical anesthetics including lidocaine cream, to minimize discomfort with insertion. Special procedural rooms oriented toward children are often used with helpful visual distractors like dolls, toys, stuffed animals, videos, or support of child life specialists.[19] See Figure 1.16[20] for an image of toys used as distractors with a hospitalized pediatric patient.

Providing education to the parents regarding the process of the IV start and what might work best for the child ahead of the procedure can be helpful for ensuring cannulation occurs with minimal complications. Parents can often be excellent sources of support when pediatric patients undergo invasive procedures, but it is important that the parents are comfortable and informed regarding their role and the manner in which they will offer assistance.

There are also modifications nurses can make independently based on their clinical knowledge of a patient’s condition. For example, many elderly patients who receive steroids have vessels that are very fragile and difficult to cannulate. Nurses may modify the procedure by omitting the use of a tourniquet. This decreases pressure in the vessel during venipuncture and helps to prevent the vein from rupturing or “blowing" (i.e., leaking blood due to rupture). The use of a tourniquet may also be omitted to prevent skin tears.

Many elderly patients have less subcutaneous tissue as a result of the aging process, and the nurse may note that their vessels, particularly those located in the hands, appear more superficial than is seen in younger patients. See Figure 1.17[21] for an image of superficial veins. As a result, the experienced nurse may modify their vessel cannulation technique by inserting the needle at a decreased or shallower angle when attempting cannulation. Decreasing the angle of insertion will provide less chance of passing the needle through the vessel when first puncturing through the skin.[22]

General Guidelines for Maintaining Peripheral Venous Access Sites

Health care agencies have policies regarding site assessment, flushing, maintenance, and dressing changes. The following general guidelines apply to maintaining peripheral IV access sites:

- Site assessment: In inpatient and nursing facilities, peripherally inserted IV sites should be assessed at least every four hours and more frequently for patients receiving infusions of vesicant medications. Sites should be assessed every 1-2 hours for patients who are critically ill/sedated or have cognitive deficits and every hour for neonatal/pediatric patients.[23] In outpatient or home settings, the patient or caregiver should be taught to check the site every four hours during waking hours for signs of complications and immediately report concerns to their health care provider.[24]

- Duration of site: Traditionally, IV access sites were changed every 72-96 hours, but research indicates no clear difference in rates of infection, phlebitis, mortality, or pain if catheters are kept in place until IV therapy is complete or a complication occurs requiring site discontinuation.[25]

- Routine flushing of saline locks: When not in continuous use, saline locks should be flushed with two times the amount of external catheter length plus catheter (i.e., 5 mL in adults) with normal saline every 8-12 hours to ensure patency.[26]

- Securement devices: To maintain integrity of the IV site and prevent infiltration and other complications, proper securement devices should be used, when available, to keep the IV secure and prevent dislodgement. Examples of securement devices are stat locks, chevron tape, arm boards, and arm wraps.

- Peripheral IV dressing changes: Gauze dressings should be changed at least every two days and transparent dressings at least every seven days. They should be changed immediately if the dressing becomes visibly soiled, loosened, dislodged, or if there is any moisture, drainage, blood, or compromised skin.[27]

- Site care: Protective measures for the IV site include no tub baths or soaking and wrapping with a protective covering if showering. Restrictive clothing should be avoided, and blood pressure should be taken in an arm without an IV site present.

- "2134_Thoracic_Upper_Limb_Veins.jpg" by OpenStax College is licensed under CC BY 3.0. Access for free at http://cnx.org/content/col11496/1.6/ ↵

- "3029775415_7458f6461b_o.jpg" by charcoal soul is licensed under CC BY-ND 2.0 ↵

- Engström, Å., & Forsberg, A. (2019). Peripheral intravenous catheter difficulty – A clinical survey of registered nurse and critical care nurse performance. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 28(3-4), 686-694. https://doi.org/10.1111/jocn.14668 ↵

- Takahashi, T., Ryoko, M., Abe-Doi, M., Miyahara-Kaneko, M., Chiho, K., Nakamura, M., Mariko, M., Chieko, K., & Hiromi, S. (2020). Preventing peripheral intravenous catheter failure by reducing mechanical irritation. Scientific Reports, 10(1), 1550. http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-56873-2 ↵

- Gorski, L. A., Hadaway, L., Hagle, M. E., Broadhurst, D., Clare, S., Kleidon, T., Meyer, B. M., Nickel, B., Rowley, S., Sharp, E., & Alexander, M. A. (2021). Infusion therapy standards of practice. Journal of Infusion Nursing, 44(Suppl 1S), S1–S224. https://doi: 10.1097/NAN.0000000000000396.org ↵

- This work is a derivative of StatPearls by Beecham & Tackling and is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- "Color-coding_of_IV_cannulas.jpg" by Dr.Vijaya Chandar is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0 ↵

- This work is a derivative of StatPearls by Beecham & Tackling and is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- "IV_Catheters_(9).JPG" by Intropin is licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0 ↵

- This work is a derivative of Clinical Procedures for Safer Patient Care by British Columbia Institute of Technology and is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- Simin, D., Milutinović, D., Turkulov, V., & Brkić, S. (2018). Incidence, severity and risk factors of peripheral intravenous cannula‐induced complications: An observational prospective study. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 28(9-10), 1585-1599. https://doi.org/10.1111/jocn.14760 ↵

- Gorski, L. A., Hadaway, L., Hagle, M. E., Broadhurst, D., Clare, S., Kleidon, T., Meyer, B. M., Nickel, B., Rowley, S., Sharp, E., & Alexander, M. A. (2021). Infusion therapy standards of practice. Journal of Infusion Nursing, 44(Suppl 1S), S1–S224. https://doi: 10.1097/NAN.0000000000000396.org ↵

- Gorski, L. A., Hadaway, L., Hagle, M. E., Broadhurst, D., Clare, S., Kleidon, T., Meyer, B. M., Nickel, B., Rowley, S., Sharp, E., & Alexander, M. A. (2021). Infusion therapy standards of practice. Journal of Infusion Nursing, 44(Suppl 1S), S1–S224. https://doi: 10.1097/NAN.0000000000000396.org ↵

- Gorski, L. A., Hadaway, L., Hagle, M. E., Broadhurst, D., Clare, S., Kleidon, T., Meyer, B. M., Nickel, B., Rowley, S., Sharp, E., & Alexander, M. A. (2021). Infusion therapy standards of practice. Journal of Infusion Nursing, 44(Suppl 1S), S1–S224. https://doi: 10.1097/NAN.0000000000000396.org ↵

- Wang, J., Li, M. M., Zhou, L. P., Xie, R. H., Pakhale, S., Krewski, D., & Wen, S. W. (2022). Treatment for grade 4 peripheral intravenous infiltration with type 3 skin tears: A case report and literature review. International Wound Journal, 19(1), 222–229. https://doi.org/10.1111/iwj.13624 ↵

- Gorski, L. A., Hadaway, L., Hagle, M. E., Broadhurst, D., Clare, S., Kleidon, T., Meyer, B. M., Nickel, B., Rowley, S., Sharp, E., & Alexander, M. A. (2021). Infusion therapy standards of practice. Journal of Infusion Nursing, 44(Suppl 1S), S1–S224. https://doi: 10.1097/NAN.0000000000000396.org ↵

- Gorski, L. A., Hadaway, L., Hagle, M. E., Broadhurst, D., Clare, S., Kleidon, T., Meyer, B. M., Nickel, B., Rowley, S., Sharp, E., & Alexander, M. A. (2021). Infusion therapy standards of practice. Journal of Infusion Nursing, 44(Suppl 1S), S1–S224. https://doi: 10.1097/NAN.0000000000000396.org ↵

- This work is a derivative of Clinical Procedures for Safer Patient Care by British Columbia Institute of Technology and is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- Olsen, K., & Weinberg, E. (2017). Pain-less practice: Techniques to reduce procedural pain and anxiety in pediatric acute care. Clinical Pediatric Emergency Medicine, 18(1), 32–41. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpem.2017.01.007 ↵

- "DN-SD-06-07603.jpeg" by Department of Defense. American Forces Information Service. Defense Visual Information Center. (1994 - 10/26/2007) is licensed in the Public Domain. ↵

- "the-elderly-g2ddfbcc36_1920.png" by f_qian on Pixabay is licensed under CC0 ↵

- Simin, D., Milutinović, D., Turkulov, V., & Brkić, S. (2018). Incidence, severity and risk factors of peripheral intravenous cannula‐induced complications: An observational prospective study. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 28(9-10), 1585-1599. https://doi.org/10.1111/jocn.14760 ↵

- Gorski, L. A., Hadaway, L., Hagle, M. E., Broadhurst, D., Clare, S., Kleidon, T., Meyer, B. M., Nickel, B., Rowley, S., Sharp, E., & Alexander, M. A. (2021). Infusion therapy standards of practice. Journal of Infusion Nursing, 44(Suppl 1S), S1–S224. https://doi: 10.1097/NAN.0000000000000396.org ↵

- Gorski, L. A., Hadaway, L., Hagle, M. E., Broadhurst, D., Clare, S., Kleidon, T., Meyer, B. M., Nickel, B., Rowley, S., Sharp, E., & Alexander, M. A. (2021). Infusion therapy standards of practice. Journal of Infusion Nursing, 44(Suppl 1S), S1–S224. https://doi: 10.1097/NAN.0000000000000396.org ↵

- Webster, J., Osborne, S., Rickard, C. M., & Marsh, N. (2019). Clinically-indicated replacement versus routine replacement of peripheral venous catheters. The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 1(1), CD007798. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD007798.pub5 ↵

- Lee, P. T., & Terry, J. (2021). Changing practice to using pre-filled syringes for flushing IV cannulas. British Journal of Nursing, 30(14), S14–S22. https://doi.org/10.12968/bjon.2021.30.14.S14 ↵

- Gorski, L. A., Hadaway, L., Hagle, M. E., Broadhurst, D., Clare, S., Kleidon, T., Meyer, B. M., Nickel, B., Rowley, S., Sharp, E., & Alexander, M. A. (2021). Infusion therapy standards of practice. Journal of Infusion Nursing, 44(Suppl 1S), S1–S224. https://doi: 10.1097/NAN.0000000000000396.org ↵

The inflammation of the vein’s inner lining, the tunica intima.

A condition that occurs when a nonvesicant solution (IV solution) is inadvertently administered into surrounding tissue.

A condition that occurs when vesicant solution (medication) is administered and inadvertently leaks into surrounding tissue, causing damage to surrounding tissue.

A condition caused by excess fluid accumulation in the lungs due to excessive fluid in the circulatory system.

The presence of air in the vascular system that occurs when air is introduced into the venous system and travels to the right ventricle and/or pulmonary circulation.

An embolism that occurs when a small part of the cannula breaks off and flows into the vascular system.

An infection caused by microorganisms introduced into the bloodstream through the puncture site, the hub, or contaminated IV tubing or IV solution, leading to bacteremia or sepsis.

A blood vessel leak due to rupture.