Chapter 9: Using Observation Methods, Tools and Techniques to Gather Evidence

Gina Peterson and Emily Elam

Chapter Objectives

In this chapter, you will be learning about:

- Taking the First Step: Gathering Baseline Data

- Understanding the Child

- Let’s Get Started

- A Closer Look at Observation Methods, Tools and Techniques

- Running Records

- Frequency Counts

- Checklists

- Anecdotal Records

- Work Samples

- Learning Stories

- Technology

Introduction

Observing children as they play, learn, and socialize with others is an integral part of every early educator’s daily routine. According to the California Preschool Program Guidelines, when early caregivers and preschool teachers “regularly observe and document brief, subtle moments of children’s learning through play, those records help parents and others understand how useful and important play is in helping children to learn and grow” (p. 32-33). In this chapter, we will examine the various observation methods, tools and techniques that can be used to gather information about the children in your care. Although teachers may favor one method over the other, it is recommended that teachers utilize several methods, tools and techniques so that they can gather a well- rounded perspective of each child. To truly understand the “whole child” it is important to realize that observation and documentation is an ongoing process that begins with gathering “baseline data.”

Taking the First Step: Gathering Baseline Data

In order to truly measure the learning, growth, and development of a child over time, there needs to be a point of reference, or a starting point. Baseline data provides a starting point. As recommended by the California Department of Education, in the Desired Results Developmental Profile (DRDP), to establish a baseline, children should be observed “within 60 calendar days of enrollment and [formally assessed] every 6 months thereafter” (DRDP, 2015, p. ii). More specifically, any time a child starts your program, or any time you introduce a new concept, topic or theme, it would be beneficial to gather baseline data. With each observation the goal is to track – What the child can do. Then, as we review each observation, we further consider what the child has the potential to do. Knowing specific details about how the child responds to the activities we have planned, and how the child is interacting with their peers, allows intentional teachers to make informed decisions that are in the best interest of the child. Baseline data allows us to create individualized activities and enriched learning opportunities and set up engaging environments where each child can feel empowered, challenged and well cared for.

Here is an example:

Aaron is 3.5 years old and this is his first time in preschool. To see whether Aaron can write his name, you would set out writing materials (markers or crayons, paper and possibly stencils), and you would observe Aaron at the writing center. To gather baseline data, you could use an Anecdotal Note to record how Aaron holds the markers – is he using the palmer grasp or the pincher grasp? Is he using his right or left hand? You would also want to note what Aaron created – did he write his name, draw a picture or scribble? If Aaron scribbled, he might not be ready to use lined paper to write his name or to journal a story. Rather than planning an activity that would require Aaron to write between the lines, it may be more beneficial to plan activities that would help him further develop his fine motor skills. Perhaps you would set out activities that would build his pincher grasp like play dough or stringing beads. Once you observe Aaron’s progression and his “signs of readiness”, then you would reintroduce writing between the lines.

Understanding the Child

Many of the same tools and techniques you use to gather baseline data, you will continue to use to support the whole child. This includes screening, planning curriculum, and assessing development. Every observation you complete provides valuable information that you can use to be more intentional and more responsive. When we observe the children in our care, we can learn about their:

- interests, abilities and preferences

- developmental skill level (cognitive, language, social, emotional, physical)

- how they strategize in social situations

- how they approach learning opportunities

- personality and temperament

Let’s Get Started

Whether you are doing a planned observation, or you decide to do a spontaneous observation, you will need some essentials. An intentional teacher is a prepared teacher, and here are a few things you will need:

- Something to write on – paper, sticky notes, color coded index cards, clipboard, notebook

- Something to write with – colored ink pens, sharpie markers

- Something to record with – photo camera, video camera, tape recorder, printer

- Something to store your documentation in – a filing cabinet, accordion file folder, portfolio

- Blank observation tool templates – checklists, frequency counts, ABC, anecdotal notes

- Some extras – tape, stickers, paper clips, stapler, batteries, dictionary

A Closer Look at Observation Methods, Tools and Techniques

No single observation can give you all the information you will need about a child’s development. In order to truly understand a child’s unique attributes, preferences, personality and strengths, you must observe them consistently, using several documentation tools and techniques. Each observation method has strengths and limitations. In this section, we will review some of the more commonly used techniques and tools that teachers use to gather objective observation evidence: Running Record; Checklists; Frequency Count; Anecdotal Record; Work Sample; Learning Story; and Technology.

Figure 9.1 Notetaking is one of the oldest forms of recording observations[1]

Running Record

One of the oldest observation methods used in early child education is the Running Record. Running Records are considered by some as an “informal method” of observation as compared to Narrative Description or Specimen Records which are considered to be a more “formal method” of collecting data. The primary difference between the two methods is that with a Running Record, evidence is gathered in a more spontaneous (informal) manner as it occurs, whereas with a Narrative Description a (formal) plan would be arranged in advance, prior to the observation. More specifically, you would schedule a day, time and setting, you would select a specific child or group of children, and you would decide on the purpose, reason or focus of your observation (e.g. cognitive skills, social interactions, play patterns). Both methods provide rich, detailed evidence and both methods provide written accounts of everything you see and hear a child doing during a specific timeframe (Bentzen, 2009).

For the purpose of this text, we will use the term Running Record and recommend that you, as an intentional teacher, conduct Running Records (whether spontaneous or planned, informal or formal) as part of your regular or routine observations. The primary goal for using a Running Record is to “obtain a detailed, objective account of behavior without inference, interpretations, or evaluations” (Bentzen, 2009, p.112). You will know you have gathered good evidence when you can close your eyes and you can “see” the images in your mind as they are described in your Running Record (Bentzen, 2009).

Collecting Your Data

All you need is time, paper and a pen to gather your observation evidence. The goal with a running record is to write down everything you see and hear – exactly as it occurs, without adding any comments or attaching any opinions. As the saying goes, “just the facts, ma’am!” With the Running Record format, not only will you highlight children’s behaviors, you will record the “setting, situation and sequence” in which the behavior occurred. Be as descriptive as possible and yet be as concise as possible. Children move quickly, so you must write quickly. When conducting a running record, you need to be out of ratio. You are to step back and observe from a distance. Do not interfere with the child’s natural play, do not ask questions and do not run after them. Be as invisible as possible.

Organizing your Data

As you collect rich, detailed data throughout the school year, you will begin to recognize patterns of development, and you will see each child’s unique attributes, personalities, and abilities as they emerge. Be sure to date all your running records; having 12-24 children in your classroom can add up to a lot of running records. You will need to store your running records safely in a portfolio or file folder. When it comes time to assess a child’s development, you will be able to look back and review all the evidence you have collected and to monitor the child’s progress over time.

Note: A Running Record is an ideal observation method for “students”. Teachers may not always have the time or staff coverage to conduct a Running Record.

Table 9.1: Running Record

|

Advantages |

Disadvantages |

|

|

Let’s Practice Gathering Evidence

Example 1:

Running Record: On 7/2/2019, Jorge played in the sandbox for 20 minutes.

What did you “see” with this example? What was the setting, situation and sequence of events?

What did you learn about Jorge?

Was the evidence objective? Was the evidence descriptive?

Let’s try again.

Example 2:

Running Record: 7/2/2019. Time: 10:10am

During outside play and exploration, the following activities were available: bikes, sandbox, sensory table with goop, hula hoops, balls and a reading area with a basket of books. Jorge played in the sandbox for 20 minutes. With his left hand, Jorge dug a hole using a shovel. Jorge asked Julissa if he could have the dinosaur, “When you are finished, can I have the dinosaur for my cave?” Julissa handed Jorge the dinosaur and said, “Can I see?” Jorge nodded his head up and down.

At 10:30am, the teacher announced that it was time to clean up. Jorge stood up, dropped his shovel, ran over to the door and got in line. While in line, Jorge waved his hands and said “Come on Max. Come on. Here. Come here.” Max ran over and stood next to Jorge in line.

What did you “see” with this example? What was the setting, situation, and sequence of events?

What did you learn about Jorge?

Was the evidence objective? Was the evidence descriptive?[2]

|

Running Record Template #1 |

|

Date: Start Time: End Time: Setting: Activity Area: Who did you observe: |

|

Running Record |

|

|

|

Running Record Template #2 |

|

Date: Start Time: End Time: Setting: Activity Area: Who did you observe: |

|

Running Record |

Interpretation |

|

|

|

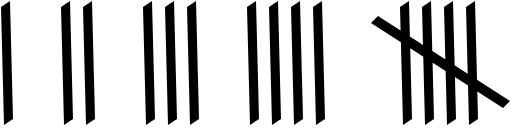

Figure 9.2 When is a frequency count used? Whenever you need to tally and record how many times a behavior is occurring.[3]

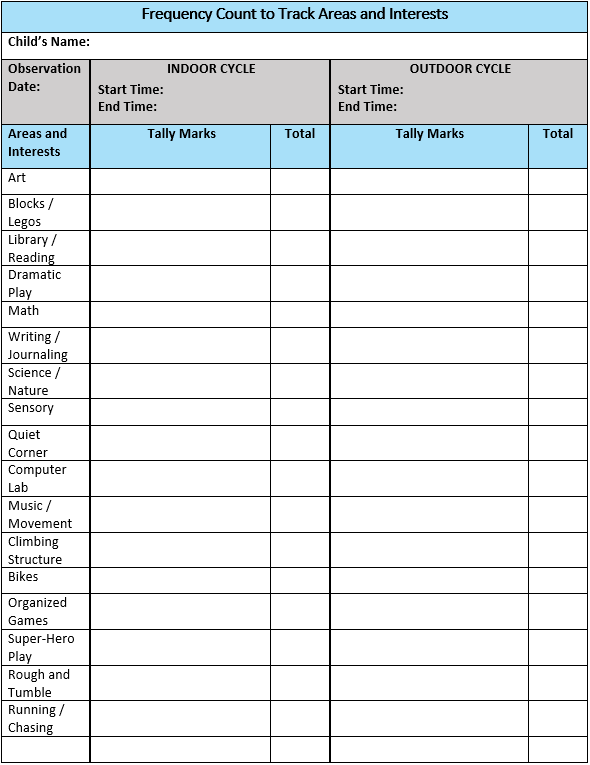

Frequency Counts (Time or Event Sampling)

A Frequency Count is an informal observation method that is used to gather information about a child’s interests, social interactions, play patterns, and temperamental traits. As the teacher observes the children at play, a tally mark is made every time the noted behavior or action occurs within a set timeframe. Frequency Counts are also used to track undesirable or challenging behaviors, as well as ideal or positive behaviors.

Collecting your data

To create a Frequency Count, you must first decide on what social interactions, behaviors, interest areas, or types of play you want to monitor. You may decide to track your child during one focused activity or timeframe, or you may map out what a typical day might look like for your child and track all the interactions and experiences they engage in throughout the day. Either way, as you observe your child, you will make a tally mark every time they play in a specified area or display one of the action items as listed on your Frequency Count.

Here are some examples of how you might use a Frequency Count to gather data:

- Sue has been hitting a lot lately and displaying other challenging behaviors. You will want to track how many times she hits in a typical day, along with any other challenging behaviors. You will also want to track where the incidents are occurring – are there more incidents while inside the classroom or are things happening during outside play? You will want to look at when the incidents are occurring most often– are there more incidents earlier in the day or later in the day? You may want to observe what is happening at drop-off time, mealtime and at naptime. Lastly, you may want to track who Sue is socializing with and how she plays with others. Does Sue display a consistent play pattern (parallel play, cooperative play, onlooker play)?

- Thomas is a new student and his mother wants to know how he is doing. You may want to observe which centers Thomas goes to most often throughout the day and track his interests. You may also want to track whether he plays alone or with other children.

- You and a child in your class are constantly butting heads. How can you create a supportive environment and provide a “goodness of fit?” You may need to track the child’s temperamental traits and observe how the child approaches activities and how they respond to social situations.

Organizing Your Data

After you have collected all the data for that timeframe, count the tally marks. What can you interpret from this data? What areas or action items received a high number of tally marks? What areas or action items received a low number of tally marks? Do you see any patterns? As you consider those questions, reflect on a plan of action that you might use to further support that child’s development.

Table 9.2: Advantages and Disadvantages of Frequency Data

|

Advantages |

Disadvantages |

|

|

Checklists

Checklists are an efficient and practical way to collect information about a child’s development. Checklists are based on “developmental norms” as determined by developmental theorists. With each age range, there are certain expectations and skills that a child should be able to achieve. Checklists are designed to track a child’s competencies in all the developmental domains including physical, cognitive, language, social and emotional. With a checklist, teachers can easily see what a child can do, as well as note what areas of development need further support. Teachers can create their own checklists based on certain skill sets, or they can download a formal developmental milestone checklist from a reputable source to look at a child’s full range of development. Checklists can be used to track a large group of children or an individual child.

Collecting your data

Whether you design your own checklist or download one, use it regularly to collect data. The checklist can be utilized in two ways:

- You can observe a child on a specific day while they are engaged in an activity (either child-directed or teacher-directed). As you observe, you will check off the skills or milestones that the child can do on that day, at that moment.

- You can also review data from other observations (e.g. running records or anecdotal notes, work samples) that you collected, and ADD any other skills or milestones that were mastered during those previous observations.

*Note: It is vital that you note the dates that you observed the skills being mastered. A check mark alone will limit the reliability and validity

Organizing your data

Schedule a day and time to regularly review your observation data. Data collected from other observations (mastered milestones and developing skill sets) can be added to the checklist so you can clearly see a child’s progress over time. You may use colored pens to track all the different dates that milestones were achieved. As you review the checklist, what can you interpret from this data? Does the child demonstrate strengths in any of the developmental domains or areas of learning? Which milestones and skills need further support? As you consider those questions, reflect on a plan of action that you might use to further support that child’s development. How can you provide opportunities for the child to gain more practice? What adjustments need to be made to make the activity more challenging? What extensions can be added to continue the learning pattern?[4]

Table 9.3: Advantages and Disadvantages of Checklists

|

Advantages |

Disadvantages |

|

|

Checklist for Physical Milestone

Perceptual Movement

|

Skills |

Can Do |

Needs Further Support |

Date and Evidence |

|

Moves in a zig-zag pattern – able to change directions with ease |

|

|

|

|

Plays follow the leaders and mirrors others movements |

|

|

|

|

Moves body to music cues |

|

|

|

|

Speeds up and slows down while running or riding bike |

|

|

|

Gross Motor Movement

|

Skills |

Can Do |

Needs Further Support |

Date and Evidence |

|

Completes tasks on an obstacle course |

|

|

|

|

Changes directions and stops quickly while running |

|

|

|

|

Pumps legs on a swing |

|

|

|

|

Runs and uses arm and legs in opposition |

|

|

|

|

Climbs |

|

|

|

|

Walks up and down stairs with one foot on each stair step |

|

|

|

|

Hops on one foot |

|

|

|

|

Kicks balls

|

|

|

|

|

Catches and throws (bean bags and balls) |

|

|

|

|

Pedals a 3-wheeled bike (tricycle) |

|

|

|

|

Bounces a ball several times |

|

|

|

|

Walks along a balance beam |

|

|

|

|

Jumps up and down, jumps forward using arms |

|

|

|

Fine Motor Movement

|

Skills |

Can Do |

Needs Further Support |

Date and Evidence |

|

Cuts with scissors

|

|

|

|

|

Uses writing utensils (markers, crayons, pencils) to scribble |

|

|

|

|

Prints letters, numbers

|

|

|

|

|

Uses stamps and stamp pad

|

|

|

|

|

Strings beads

|

|

|

|

|

Pours liquid into cup

|

|

|

|

|

Manipulates, moves and picks up small objects |

|

|

|

|

Uses utensils to feed self

|

|

|

|

|

Buttons and zips

|

|

|

|

|

Peels a banana or orange

|

|

|

|

|

Opens and closes a Ziploc baggie |

|

|

|

|

Scoops and pours materials (sand, dirt, rocks, beads) |

|

|

|

Anecdotal Records

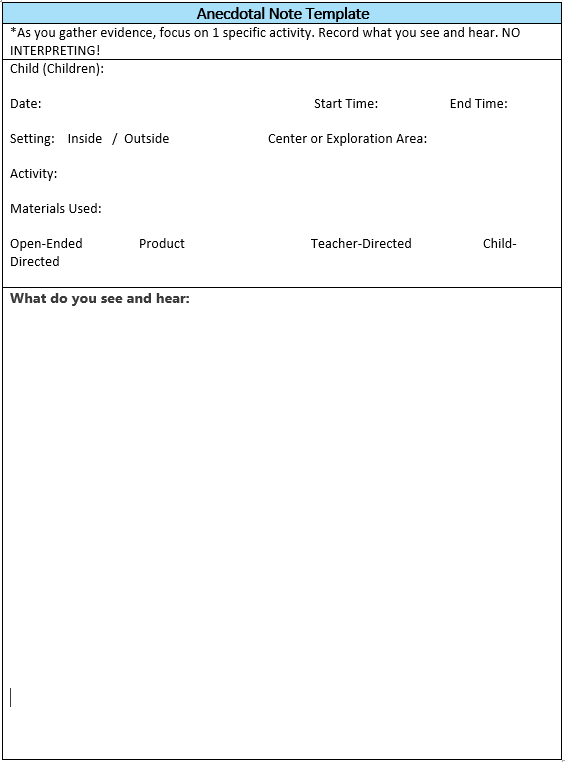

An Anecdotal Record is “an informal observation method often used by teachers as an aid to understanding the child’s personality or behavior. It provides a running account of behavior that is either typical or unusual for the child” (Bentzen, 2009, p. 178). Anecdotal Records, also referred to as “anecdotal notes,” are direct observations of a child that offer a window of opportunity to see into a child’s actions, interactions and reactions to people and events. An Anecdotal Record is an excellent tool that provides teachers with a collection of narratives that can be used to showcase a child’s progress over time. As compared to a Running Record, Anecdotal Records provide brief notes that are focused on a specific event or activity.

Collecting Your Data

To gather effective observation evidence, you need to include the following components:

- Accurate and specific details of the event (vivid descriptions exactly as you see and hear them happening – do not summarize, assume or make judgments)

- The context, setting and situation that surrounds the event (the where, when, who, what, and how)

- Objective facts about the child’s behavior and interactions (report actions and conversations)

- Write records in the past tense

Here are some examples of observation evidence you might want to gather:

- Social interactions with peers

- Everyday routines, like mealtime and transition times

- How they utilize materials at the various centers (library, block, math, science, art, music)

- How they engage in teacher-directed activities (structured learning opportunities)

- How they engage in child-directed activities (open exploration opportunities)

- How they are inside and how they are outside

Organizing your Data

Once you have completed the Anecdotal Record you will take a moment to interpret the data. You will look for patterns and you will note whether the data reflects typical or unusual behavior for the child. To measure a child’s developmental progress, you will look for their strengths (skills and milestones that have been mastered) and their needs (skills and milestones that the child needs further support with). The summary notes help you to clarify instructional recommendations (adjustments that you will make to the environment to accommodate the child’s individual learning style). The notes you take can help you generate developmentally appropriate lesson plan activities and interactions. All Anecdotal Records need to be dated and stored safely in the child’s portfolio or file folder.

Table 9.4: Advantages and Disadvantages of Anecdotal Record

|

Advantages |

Disadvantages |

|

|

|

|

Pin It! Writing an Anecdotal Note Watch this video to learn how to write an anecdotal note: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=GsXvbflrLu4&t=92s Watch this video to learn how to use an anecdotal note: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=KAczTiO1rUg&t=3s |

Figure 9.3 A Childs Masterpiece.[5]

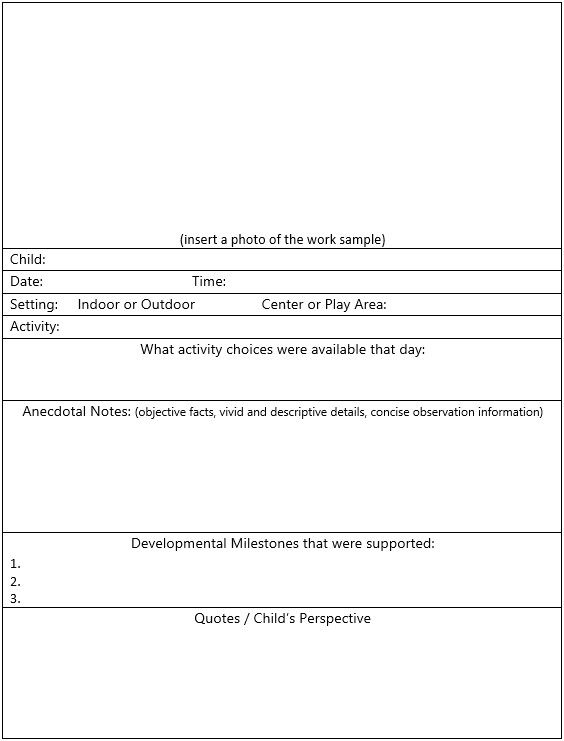

Work Samples

Teachers have been collecting pieces of children’s artwork and posting them on the classroom walls forever. Not only do the children enjoy seeing their work of art on display, parent’s appreciate seeing their child’s work as well! To create an official work sample however takes more effort than hanging a picture on the wall. What exactly is a work sample? A work sample is a tangible piece of evidence that showcases a child’s effort, progress and achievement. More specifically, not only does a work sample highlight the final product, it can highlight the process as well, by highlighting the child’s problem-solving efforts, experimentation methods or collaboration skills. Work samples are authentic artifacts that provide information about the child’s learning experience.

Collecting your data

Work samples can be gathered throughout the school year. Typically, you would collect a variety of samples that highlight the child’s overall development in each of the developmental areas: Physical; Cognitive; Language; Social -Emotional. More specifically, you might include a child’s drawing or painting, a writing sample from their journal, a cutting sample, or photographs of the child engaged in activities such as building a block tower or sandcastle or riding a bike.

Organizing your data

Whether you post a work sample on the classroom wall (using a documentation board) or you collect a sample for a child’s portfolio, you must add documentation. Not only will documentation help families recognize the value of play, it reinforces the concept that every activity is an opportunity to learn. For accuracy, be sure to include the following information: Child’s Name; Date; Setting; and an Anecdotal Note with a description about how and why the sample was collected. Work samples should be organized in a chronological manner to showcase progress over time. Be sure to store work samples in a safe place like a file-folder or portfolio, or electronically in a computer file.

Table 9.5: Advantages and Disadvantages of Work Samples

|

Advantages |

Disadvantages |

|

|

Work Sample Template

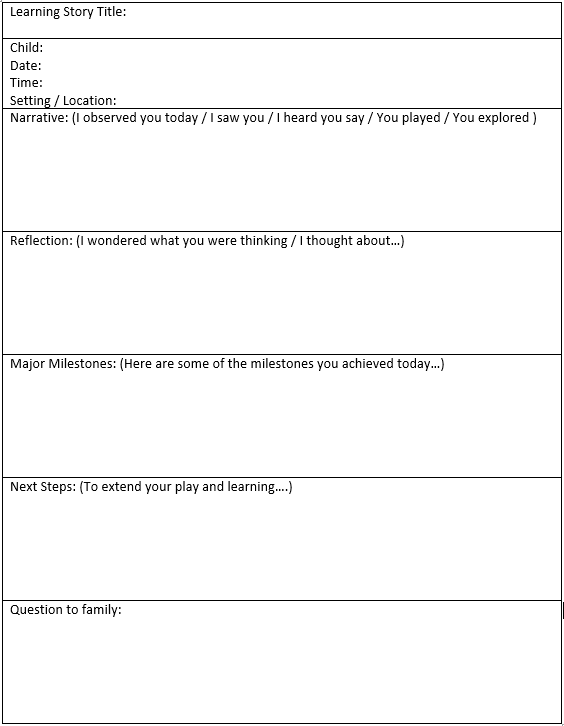

Learning Stories

In an article published in NAEYC’s Teaching Young Children, Judy Pack shares her thoughts on Learning Stories, “I like to think of it as observing small moments that provide big opportunities.”[6]

As compared to Running Records or Anecdotal Notes, a Learning Story is an observation method that is written in a narrative story format to highlight a child’s learning. The Learning Story communicates more than facts about how a child approaches or accomplishes tasks, it spotlights key moments in a child’s day and focuses on their strengths. When writing a Learning Story, a teacher not only writes down what she saw and heard, she can also write down what she thought about while she watched the child play. More than that, this method encourages the child and their families to be active participants in the reflective process. When the teacher shares the Learning Story with both the child and family members, they can add their comments, ask follow-up questions and make suggestions on how to move forward based on what was reported in the Learning Story. One unique aspect of Learning Stories is that when used regularly, they can help teachers connect to families and build strong, respectful relationships.[7]

Gathering your data

Whether you plan an observation, or you spontaneously watch a child as they play, and whether you observe during a teacher-directed activity or during a child-directed moment, you can gather some suitable evidence for your Learning Story. As you watch and listen to a child at play, you can take some pictures and jot down some objective and descriptive facts that you will use to write a story. As suggested by Park (2016), if you want to learn about a child’s interests and capabilities, and how they process information; you will want to watch the following:

- Engagement: How long does the child stay focused and engaged in an activity?

- Intentionality: Does the child have a goal in mind or express a plan of action?

- Relationships: Does the child interact or connect with others?

- Learning disposition: Does the child have a particular approach to figuring things out or a preferred style of learning?[8]

Organizing your data

Whether you want to write a short paragraph or a full page, there are some key components that you must include in your Learning Story. We will refer to the EarlyWorks tool and the guidelines as recommended by Tom Drummond to write up your observation data.[9] Your Learning Story should include the following:

- A Title – All good stories have a title that draws the reader in. Titles can act as a reminder of the content of the learning story, making it easy for educators to revisit at a later time.

- Photos – Learning Stories should have at least one photo. Visual images evoke emotion and a connection to the story.

- Narrative – This is where the storyteller (you) describes what is seen and heard. It is best to write in the first person, using “I…”. The narrative is the body of the story and highlights authentic observation evidence (facts and vivid details).

- What it means – This is where the storyteller (you) interprets the learning that took place. It is best to write in the second person, using “You…”.

- Opportunities and Possibilities – This is where you reflect on planning for the next step and building on what the child knows.

- Family & Child’s Voice – The child’s family is encouraged to provide their understanding of the story. Families can create stories and provide valuable insight into the learning that happens at home. Children can also share their perspectives.[10]

- *Note: A Learning Story Template is available

Table 9.5: Advantages and Disadvantages of Learning Stories

|

Advantages |

Disadvantages |

|

|

Learning Story Template

Technology

Finding ways to utilize technology into regular routines can make collecting observation evidence much more efficient for busy teachers. Photographs, video, and audio recordings can authentically capture children’s explorations, investigations, play and learning experiences in the actual moment. With this type of documentation, teachers can replay key moments in a child’s day to look for specific interactions, play patterns, developmental milestones, struggles and accomplishments. With this technique, teachers can also listen for language development by recording actual conversations that children are having with their peers. Teachers can also monitor how children problem solve and can tape special moments as well as capture every day moments. As with work samples, teachers can share their observation evidence with the children. Children are fascinated with seeing and hearing themselves. This type of documentation provides the most authentic evidence of all the observation methods.

Collecting your data

There are numerous ways to incorporate technology into your classroom. It is important to keep in mind that each early care and education program would have their own protocol, policies and procedures regarding the use of technology to document children’s learning, growth and development, so be sure to verify what you can and cannot do. Here are a few suggestions that you may want to incorporate:

- Use a camera, laptop, tablet, or smartphone to record observations and take pictures

- Ask a child to dictate a story and you can type it up on a computer or use an audio recorder

- Scan or make copies of children’s work, such as drawings or writing, to create a visual timeline that shows a child’s skill development over time.

- Use email or a parent communication app to post work samples

- Use voice-to-text software to document important discussions. For example, children can explain how they created their piece of art.

- Take pictures of three-dimensional work. For example, woodworking projects, block towers, sandcastles, and culinary creations.

- Film dramatic plays and musical performances that the children produce.

- Use a video camera to document how children are progressing with their developmental milestones in each of the domains. For example, look at playful interactions to track social-emotional development; watch children on the playground to track physical development; observe how children tackle science or math activities to track cognitive development.[11]

Organizing your data

Observation data can be conveniently stored on a computer and each child can have their own digital portfolio or file folder. For every child, you would include photos of them at play, photos of their work samples, and any audio recordings or video clips that you may have collected (as suggested above). When using smartphones to take photos or videos, you can easily upload information to your computer or transfer information to other devices. Some teachers may want to use an app to formally organize observation evidence, and some schools may purchase a program that links families to daily observations. Some centers may even use an electronic assessment program (e.g. the Desired Results Developmental Program – DRDP) to track children’s developmental progress and teachers would regularly upload observation evidence as part of the assessment process. Here are a few added suggestions on how you can organize and use stored electronic observation evidence:

- Photos can be scanned, printed and posted in the classroom

- A photo slideshow can be created for family nights or as a screen saver

- The children can watch a video montage of a themed project they completed

- Children can look at “old” photos to monitor their own developmental progress and can make comments regarding their work, their thought process and their developmental outcomes.[12]

Table 9.6: Advantages and Disadvantages of Technology

|

Advantages |

Disadvantages |

|

|

Conclusion

An intentional teacher is a skilled and thoughtful observer. With each observation, whether a running record, anecdotal note, video recording, checklist, frequency counts, learning story or work sample, they are watching and listening, and considering what do I know about this child, and how can I best support this child? As teachers gather and organize their observation data, they begin to see each child for who they are as an individual, and as a member of the classroom community. With that information, intentional teachers can set realistic expectations of what children can do. Ideally, teachers will utilize the documented data to develop developmentally appropriate activities and to create an interesting and stimulating learning environment that is designed to promote play, socialization, growth and development. Now that you have been introduced to some of the tools and techniques that are used to gather information and document a child’s development, in the next chapter, you will delve deeper to review the concepts of typical development and atypical development, and you will learn about some additional tools that can be used to track a child’s development.[13]

References

Bentzen (2009), Seeing Young Children: A Guide to Observing and Recording Behavior. Thomson Delmar Learning, Clifton Park, NY

CDE. (2015). California Preschool Program Guidelines. Retrieved from https://www.cde.ca.gov/sp/cd/re/documents/preschoolproggdlns2015.pdf

CDE (2006). Desired Results Developmental Profile. Retrieved from https://www.researchconnections.org/files/meetings/ccprc/2006-04/14/CaliforniaDRDPPreschool_Instruments.pdf

Chelsea, Wright. (2015). Using Frequency Counts to Look at Emotional Development. Retrieved from https://prezi.com/gqxjbtu-75qq/using-frequency-counts-to-look-at-emotional-development/

Child Care Initiative Project. (2018). Observation, Screening, Assessment, & Documentation. Retrieved from https://d3n8a8pro7vhmx.cloudfront.net/rrnetwork/pages/1365/attachments/original/1518049788/OSAD_Module_Feb_2018_ppt_coming_soon.pdf?1518049788

Complex Needs. (n.d.) Observational Methods. Retrieved from http://complexneeds.org.uk/modules/Module-2.4-Assessment-monitoring-and-evaluation/All/downloads/m08p110b/observational_methods.pdf

Gundlach, M. (2020). Strengths and Weaknesses of Informal Assessments: Find Out What Works. Retrieved from https://www.brighthubeducation.com/student-assessment-tools/99770-strengths-and-weaknesses-of-informal-assessments/

Head Start ECLKC. (2018). Child Screening & Assessment. Retrieved from https://eclkc.ohs.acf.hhs.gov/child-screening-assessment/learning-assessment-lfa-toolkit/guided-practices

Michigan State University. (n.d.). Methods of Observing Young Children. Retrieved from https://msu.edu/~mandrews/mary/obs__methods.htm

Modesto Junior College. (n.d.). Observing, Recording, and Reporting Children’s Development. Retrieved from http://laffranchinid.faculty.mjc.edu/Ch5.pdf

National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. (2020). Child Development and Early Learning. Retrieved from https://www.nap.edu/read/19401/chapter/8

Neaum, S. (2016). Observing and assessing children’s learning and development. Retrieved from http://study.sagepub.com/sites/default/files/Neaum%2C%20S.%20%282016%29%20Observing%20and%20Assessing%20Children%27s%20Learning%20and%20Development.%20London%2C%20Sage._.pdf

Riley-Ayers, S., Stevenson-Garcia, J., Frede, E. (n.d.). Now What? Using those “anecdotals” for intentional teaching. Retrieved from http://nieer.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/08/Using_Anecdotals_for_Intentional_Teaching.pdf

US Office of Special Educational Programs. (n.d.). Behavioral Assessment: Frequency and Interval Recording. https://iris.peabody.vanderbilt.edu/wp-content/uploads/pdf_activities/independent/IA_Frequency_and_Interval_Recording.pdf

Venpakal, P. (n.d.). Tools & Techniques for Classroom Assessment. Retrieved from https://www.academia.edu/27158440/TOOLS_and_TECHNIQUES_FOR_CLASSROOM_ASSESSMENT

- Image by Glenn Carstens-Peters from Unsplash ↵

- Red Rock Community College. (n.d.) Running Record Observation. Retrieved from https://www.rrcc.edu/sites/default/files/early-childhood-education-running-record-annotated.pdf ↵

- Image is in the public domain. ↵

- Head Start ECLKC. (n.d.). Using Checklists Highlight Video. Retrieved from https://eclkc.ohs.acf.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/video/transcripts/000981-using-checklists-highlight-video.pdf Learn the Signs. Act Early by CDC is in the public domain. ↵

- Image by Dragos Gontariu on Unsplash. ↵

- Pack, J. (2016). Learning Stories. Teaching Young Children, 9 (2). https://www.naeyc.org/resources/pubs/tyc/dec2015/learning-stories ↵

- Pack, J. (2016). Learning Stories. Teaching Young Children, 9 (2). https://www.naeyc.org/resources/pubs/tyc/dec2015/learning-stories ↵

- Pack, J. (2016). Learning Stories. Teaching Young Children, 9 (2). https://www.naeyc.org/resources/pubs/tyc/dec2015/learning-stories ↵

- Pack, J. (2016). Learning Story Observations. Teaching Young Children, December/January Vol. 9, No. 2 https://getearlyworks.com.au/learning-story-observations/ ↵

- Pack, J. (2016). Learning Story Observations. Teaching Young Children, December/January Vol. 9, No. 2 https://getearlyworks.com.au/learning-story-observations/ ↵

- Blagojevic, B. and Garthwait, A. (2020). Observing and Recording Growth and Change. Retrieved from https://www.scholastic.com/teachers/articles/teaching-content/observing-and-recording-growth-and-change/ ↵

- West Sussex County Council. (2019). Effective Practice: Observation, Assessment and Planning. Retrieved from https://www.westsussex.gov.uk/media/5555/effective_poa_and_planning.pdf ↵

- Preschool Program Guidelines by the California Department of Education is used with permission ↵