Chapter 8: Quality Counts

Gina Peterson and Emily Elam

Chapter Objectives

In this chapter, you will be learning about:

- Closing the Achievement Gap

- Not All Preschool Programs are Alike

- Process Quality and Structural Quality

- The Role of the Teacher in High-Quality Practices

- Measuring High-Quality in Early Care and Education Classrooms

- The Environment Rating Scale (ERS)

- The Classroom Assessment Scoring System (CLASS)

- Additional Methods, Tools and Techniques to Ensure High-Quality Practices

Introduction

The need for high-quality childcare continues to be a topic of interest as more and more families enter the workforce and more and more children need care. Every week, families from all socioeconomic backgrounds drop their children off at some type of childcare. According to the National Institute for Early Education Research, “In the United States, 76% of children ages three to four, receive education and care from someone other than a parent.” (NIEER, 2002). With so many children needing childcare, researchers and policymakers are tasked with figuring out how to best support the next generation of preschoolers. In this chapter, we will address the need for high-quality in early care and education as means to reduce the achievement gap between children from low to high socioeconomic families. We will also compare standard industry practices to what the field of early care and education recognizes as high-quality practices. Lastly, we will review some of the current observation methods, tools and techniques that can be used to ensure programs are implementing quality practices.[1]

Closing the Achievement Gap

Decades of research on early child development has determined that “When it comes to early care and education programs, quality is critical,” (Wechsler, Melnick, Maier & Bishop, 2016, p.1). It is suggested that thoughtfully designed preschool programs can impact and influence a child’s future learning outcomes. Not only are there short-term benefits, based on data collected from quantitative research projects (e.g. Perry Preschool, the Abecedarian Project, and the Chicago Child-Parent Centers), there are long-term benefits as well. More specifically, children from low-income homes who attended high-quality preschool programs showed higher achievement scores – especially in math and reading, as compared to their counterparts who were not able to attend a quality preschool. Furthermore, children who were enrolled in high-quality programs were less likely to be placed in special education, less likely to be retained or held back a grade, and it was noted that they were more likely to graduate from high school.[2]

Unfortunately, due to limited funding opportunities and financial restraints, there are many families who cannot afford to send their child to a high-quality preschool. “This lack of access to high-quality early childhood education perpetuates the achievement gap, evidenced by the fact that only 48 percent of low-income children are ready for kindergarten, compared to 75 percent of moderated – or high-income children” (p. 3 Center for American Progress). This data reveals that the achievement gap is problematic on many levels. Moving forward we must consider how we, as advocates and educators, can lessen the achievement gap so that all children, no matter their socioeconomic status, can get a smart start. To find possible solutions to this dilemma, let’s take a closer look at and compare standard industry practices to what the field of early care and education regards as high-quality practices.[3]

Not all Preschool Programs are Alike

As more and more children need childcare, families are faced with a tremendous task of finding “the right preschool program.” When choosing a center, some families may contemplate certain factors like cost and affordability, hours of operation and availability, and location. Some families, on the other hand, may consider the school philosophy, the education and experience of teachers, the environment and daily activities, as well as the curriculum model and guidance policies. As you can see, there are numerous possibilities to consider. Families must also decide on whether to send their child to a state-funded or faith-based program, a family childcare or a traditional preschool setting. No matter what type of program a family chooses, in the state of California all childcare centers must be licensed by the California Department of Social Services and comply with Community Care Licensing Title 22 regulations. For the purpose of this text, in order to demonstrate that all preschools are not alike, we will refer to “standard industry practice” as any state licensed childcare program and we will refer to “high-quality practice” as any childcare center that undergoes regular assessments using tools and techniques that are above and beyond the standard industry practice.

A Look at Standard Industry Practices

To legally operate a childcare program in California, a center must comply with certain licensing policies and procedures. These state regulations provide “a baseline standard and are primarily focused on protecting children from harm rather than on advancing child development and early learning,” (Workman & Ullrich, 2017, p. 3). In other words, Title 22 Regulations stipulate health and safety standards, space and square footage requirements, supervision standards, and teacher qualifications. Title 22 Regulations do not however, consider curriculum activities, age appropriate materials, or teacher-to-child interactions, nor does it address developmentally appropriate practices such as family culture and perspectives, child development theories, or principles and practices.

To ensure early childhood education programs are compliant with all state policies and procedures, a licensing analyst will conduct an annual inspection, or will evaluate a program as needed. Typically, the analyst will look at the center’s overall cleanliness and they will inspect both the indoor and outdoor environment to certify that the center is safe for the children. The analyst will confirm that the ratios are met, and that there is proper space and square footage available for each child to play and nap. The analyst will also conduct a spot check of the employee files to confirm teacher qualifications, and they will look through the children’s files to validate that the proper paperwork is signed and in complete order. To comply with state regulations and policies, a center director will need to download the California Code of Regulations, Title 22 administered by CDSS (Divisions 12 only) and follow all the mandated requirements. If any criteria are not met, the analyst will cite the program. The program will then be given a certain timeframe to rectify and correct the concern. The analyst will return to verify the problem has been fixed. Families who are considering a program can check the Community Care Licensing website to see if a center has received any “substantiated citations.”[4]

A Look at High-Quality Practices

One of the hallmarks of high-quality practices is the practice of continuously monitoring and evaluating a program’s overall effectiveness for the purpose of accountability. Therefore, in addition to complying with state licensing regulations, high-quality programs may utilize noted assessment tools and resources (e.g. ECERS, CLASS, QRIS, NAEYC’s Developmentally Appropriate Practice) to evaluate their center and staff. To guide high-quality practices, early childhood educators often look to the National Association for the Education of Young Children (NAEYC) to provide ethical pedagogy. NAEYC is a recognized professional organization committed to promoting quality early learning experiences for children, birth through age 8. Grounded by research and theory principles, NAEYC promotes best practices for children, families, teachers, administrators, stakeholders and policy makers. To ensure quality practices are being implemented, it is suggested that teachers follow NAEYC’s Developmentally Appropriate Practice (DAP) Framework:

- Teachers encourage children to be active participants in their own learning

- Teachers set reasonable expectations based on what they know about a child’s age and stage of development

- Teachers build on what children know using a variety of learning strategies, materials, meaningful experiences

- Teachers plan activities to support all aspects of development: social, emotional, physical and cognitive

- Teachers value each child’s family, language, and cultural practices

- Teachers are aware of each child’s interests, strengths, abilities and individual needs

- Teachers recognize play as a primary context in which young children learn

- Teachers establish warm, caring and respectful relationships with children, families and colleagues

- Teachers regularly assess the children’s development and the environment, and they self-reflect on their own practices (Gordon and Browne, 2016, Beginning Essentials in early childhood education 3e)

Process Quality and Structural Quality

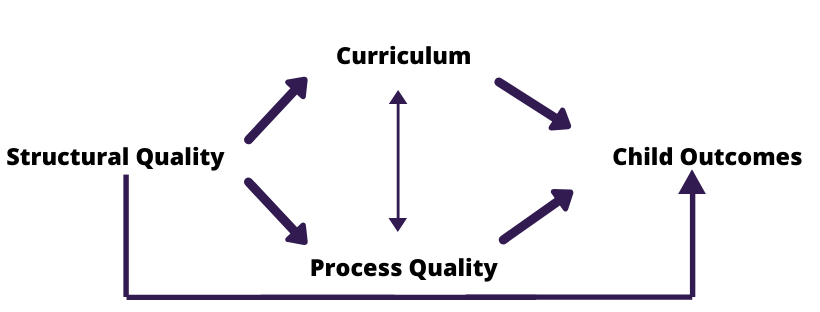

Unlike standard industry practices, high-quality practices place an emphasis on promoting positive child outcomes. The key to a high-quality program is contingent upon what happens inside the classroom environment. Let’s examine how both process quality and structural quality work together to influence positive outcomes for children.

Process quality refers to the types of interactions that occur throughout the day between the teachers, children, families, and administrators. Process quality also considers the types of materials that are available for the children to use, as well as the activities that children engage in throughout their day. Lastly, process quality takes into account the health, well-being and safety of the children. Structural quality on the other hand, refers to the features and characteristics of a program. More specifically, the class size, teacher-to-child ratios, teacher qualifications and experiences, teacher pay scale, along with the allotted square footage for play space define quality. Although process quality is thought to have a more direct impact on child outcomes as compared to structural quality, researchers and leaders in the field of early care and education agree that process and structural indicators are interrelated, and when combined together they promote the highest quality experiences.

For example, when groups are smaller, teachers tend to have more positive, supportive, and stimulating interactions with children. Warm and nurturing interactions are directly linked to children’s social competence and future academic success, and such interactions are essential to high quality. Early childhood teachers who are more highly qualified and have smaller groups can more effectively provide individualized, responsive learning opportunities. Finally, higher teacher wages have consistently been linked to higher process quality.[5]

Figure 8.1 Structural Quality directly effects Child Outcomes[6]

The Role of the Teacher in High-Quality Practices

As mentioned above, the teacher plays a vital role in orchestrating high-quality practices. In high-quality classrooms, not only must teachers create a safe and nurturing space, they must intentionally set up the environment to support children’s interests and individuality. California childcare programs serve a diverse population, therefore, an intentional teacher must also consider the cultural, linguistic, and socioeconomic status of each family enrolled in her class. The highly- qualified teacher has a deep understanding of child development, and with that knowledge she will provide appropriate materials and experiences to challenge the children in her care. In the chart below, we can see how teachers maintain high-quality practices.

Table 8.1: Classroom Environments

|

Physical environment |

The overall design and layout of a classroom, including the learning centers and play spaces, the age appropriate materials, and the child size furnishings |

|

Social environment |

The interactions that occur within the classroom between teachers, children, family members, center staff and administration |

|

Temporal environment |

The routines and daily schedules, the timing, sequence, and length of play time, the time spent indoors and outdoors engaged in child-directed and teacher-directed activities |

Here are some considerations to incorporate quality practices into your classroom to promote responsive caregiving while supporting the physical, social, emotional and intellectual development of children:

|

|

Pin It! The Building Blocks of High Quality Early Childhood Education Programs[7]

|

Measuring High-Quality in Early Care and Education Classrooms

One of the characteristics of a high-quality early childhood program is the practice of continuously monitoring children’s development, along with the environmental setting and teacher interactions. By evaluating the overall performance in these key areas, teachers, administrators and families can reflect, make necessary changes and improvements to support all students and families. There are numerous tools on the market that evaluate program quality. For the purpose of this text we will focus on just a few tools that are highly recognized and most often used in California to monitor quality practices in preschool programs.

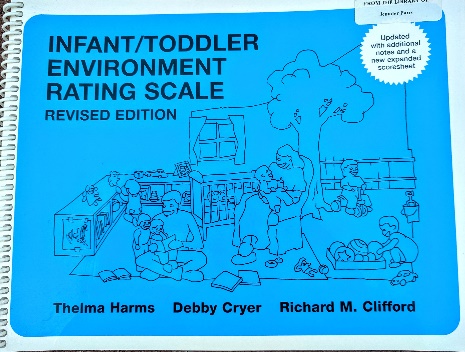

The Environment Rating Scales (ERS)

The Environment Rating Scale is a standardized assessment tool that can help caregivers, teachers, and administrators improve the quality of their program. The ERS measure process quality.

Process quality consists of the various interactions that go on in a classroom between staff and children, staff, parents, and other adults, among the children themselves, and the interactions children have with the many materials and activities in the environment, as well as those features, such as space, schedule and materials that support these interactions. Process quality is assessed primarily through observation and has been found to be more predictive of child outcomes than structural indicators such as staff to child ratio, group size, cost of care, and even type of care, for example child care center or family child care home.[8]

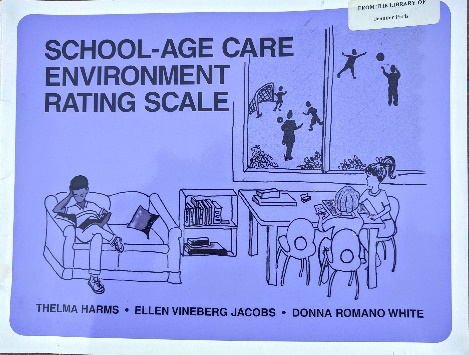

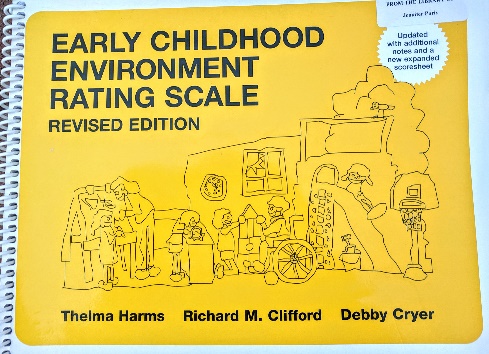

There are 4 Environment Rating Scales:

- The Infant and Toddler Environmental Rating Scale (ITERS) for programs serving young learners aged 6 weeks to 30 months

- The Early Childhood Environmental Rating Scale (ECERS) for preschool programs serving children aged 3-5 years

- The School-Age Child Environmental Rating Scale (SACERS) for afterschool programs serving children aged 5-12 years

- The Family Child Care Environmental Rating Scale (FCCERS) for family childcare programs serving children aged 6 weeks to 12 years.

Figure 8.2 Rating Scale Texts[9]

Why Use Environment Rating Scales

The scales are used in a variety of ways including for self-assessment by center staff, preparation for accreditation, and voluntary improvement efforts by licensing or other agencies. For example, in the United States:

- Several states, including California, Massachusetts, Montana, Mississippi, Kansas, Oregon, Kentucky, New Mexico, Georgia, Florida, Wisconsin, and Nebraska have also initiated quality evaluation and improvement programs using our scales. Each state is tailoring its use of the scales to its individual needs and resources.

- The state of Arkansas has trained personnel, who do assessments and provide training and technical assistance so that childcare centers and homes can increase their quality of care. Another innovative feature of the Arkansas program is that parents who select childcare facilities with an average of 4.5 or higher on our scales are eligible for two times the state childcare tax exemption. Thus, both parents and providers are being rewarded for quality improvements that benefit the children.

- The state of Colorado uses the scales in a variety of program improvement and evaluation projects. For example, Denver has a quality improvement program that uses on site consultation and training based on scale scores. Many of the centers participating in this program serve poor and minority children and their families. The state of Colorado is currently considering a tiered reimbursement system using the scales.

- North Carolina also currently uses scale scores as part of their 5-star rated license system. Centers and family childcare homes are awarded either one or two stars based on compliance with licensing standards. Programs may voluntarily apply for an additional three stars based on a set of quality measures including the licensing compliance record, teacher and director education, and the levels of process quality as measured by the appropriate environmental scale. Only the lowest level of licensing is mandatory. However, an additional fee is paid to the provider of subsidized care for each additional star earned voluntarily.

- The Oklahoma 3-star tiered license incorporates an evaluation with the scales in the second tier as a basis for quality improvement, and provides technical assistance based on scores for meeting accreditation standards. Tiered reimbursement is a part of this system.

- Tennessee is now initiating a rated license system, based on North Carolina’s experience. In their system, however, program evaluation is not voluntary, but is required yearly to create a “Report Card” that must be posted with the license so childcare consumers have access to reliable information on the quality of childcare they are using for their children. Tiered reimbursement will also be tied to scores on the scale.

- All the US military services have been using the scales routinely in their center and family childcare homes for program improvement and monitoring. The military child development system was recognized by Executive Order in 1998 for its high quality.

- Our environmental rating scales are widely used by programs as they prepare for accreditation. This is due to the fact that our scales use a format with detailed levels of quality that provides a blueprint for gradual change. The content of our scales is completely supportive of the various credentialing and accreditation programs.

The ERS Tool

As suggested by ERS, in order to provide high-quality care and education experiences to all children and their families, a childcare program must provide for the three basic needs all children have:

- Protection of their health and safety

- Building positive relationships

- Opportunities for stimulation and learning from experience

Let’s take a closer look at how to use the Early Childhood Environmental Rating Scale (ECERS-3) for preschool programs serving children aged 3-5 years. The Scale consists of 35 items organized into 6 subscales:[10]

- Space and Furnishings

- Personal Care Routines

- Language and Literacy

- Learning Activities

- Interaction

- Program Structure

Within each subscale there are indicators that are arranged in a hierarchical order with basic needs at low levels and the more educational and interactional aspects at higher levels. The requirements for each indicator must be met before the next indicator is measured. If a requirement is not met, scoring then comes to a stop.

Scoring:

1 = inadequate

3 = minimal

5 = good

7 = excellent

Empirical Research

Empirical studies using the Early Childhood Environment Rating Scale – Revised (ECERS-R) tool have generally found positive associations between the quality of early childhood programs and child development.

The ECERS-R (1998) is the revised edition of the original ECERS (1980). It is currently being used in several major studies, including the Early Head Start Study (Mathematica Corporation), and Welfare, Children and Families: A Three City Study (Columbia University, University of Chicago, and Harvard University). The original ECERS was used in the Head Start FACES study, in which over 400 classrooms are included nationwide. The preliminary results in all these studies show that the ECERS and the ECERS-R are performing very well.

Additionally, it should be noted that the ECERS and ITERS were used as the comprehensive quality measures in the National Child Care Staffing Study (Whitebook, Howes, & Phillips, 1989) and the Cost, Quality, and Child Outcomes Study (1995), the major studies of their time. The FDCRS was used in The Study of Children in Family Child Care and Relative Care (Galinsky, Howes, Kontos, & Shinn, 1994). In all of these studies, a relationship was found between higher scores on the ECERS and more positive child development outcomes in areas that are considered important for later school success. The effects of higher quality early childhood experiences have now been shown to last at least through the second grade of elementary school (Peisner-Feinberg, Burchinal, Clifford, Culkin, Howes, Kagan, Yazejian, Byler, Rustici, & Zelazo, 1999). Research is continuing to evaluate longer-lasting effects.[11]

ERS Strengths

The instrument has good test-retest reliability, high inter-rater reliability (Clifford et al., 2010), and many studies have demonstrated its predictive validity (Burchinal et al., 2008; Montes et al., 2005; Peisner-Feinberg et al., 2001). Furthermore, the results show that ECERS-R is a significant predictor of child development in two domains: physical health and well-being, and social competence.

ERS Limitation

While the ECERS-R is a useful tool to measure the quality of early childhood programs across various settings, there are some limitations. Because the Environmental Rating Scales were developed in the United States, the relevance to non-American cultural settings has been questioned (Dickinson,2006; Mathers, Singler,& Karemaker, 2012). Some have criticized that the ITERS-R scale places too much emphasis on the structural aspects of childcare (Sanders & Howes, 2013;Vermeer et al., 2008, while others are concerned that the Rating Scales fail to measure the interactions between the teacher and children and families, which is considered to be key quality factors in childcare (Bisceglia, Perlman, Schaack,& Jenkins, 2009; Helmerhorst et al., 2014).

Although the Environment Rating Scales are highly regarded, there has also been some considerable criticism. For example, a closer look at the items in the ECERS-R reveals that some items may be less relevant than others in our study’s setting—poor, rural villages in Indonesia. Item 27 outlines the provision of TV, video or computers for classroom activities. Item 3 describes the provision of soft furnishings such as carpeted space and cushions for children’s relaxation and comfort. While all of these provisions would be great to have, they are often unfeasible in rural, resource-constrained environments. In over 3 weeks of field observation, we rarely saw soft furnishings—sitting on the floor for children and adults alike is the norm in rural Indonesia – even when soft furnishings are available. We did encounter one center with a computer lab during piloting of the ECERS-R but this was a state-of- the-art center where not one but three international donors had channeled funding.[12]

ECERS FAQ Find:

When was the first ECERS tool published?

Who typically uses the ECERS tool?

Who administers the assessment tool?

How can teachers prepare for an assessment?

When was the last time the ECERS tool was updated?

How many measures are there in the ECERS?

The Classroom Assessment Scoring System (CLASS)

Research shows that all children benefit from high-quality instruction and classroom interactions, regardless of language status, race/ethnicity, or special needs (August & Shanahan, 2006; Bowman, Donovan, & Burns, 2001). When teachers provide individualized support and guidance to the children in their classrooms, they contribute to each child’s social and emotional development, which has been linked to their overall physical development and academic achievement. The CLASS tool showcases various strategies that teachers can implement to promote quality interactions. It is important to note that class does not favor any curriculum model over another.

The CLASS tool differs from other measurement tools that may address the content of the physical environment, available materials, or a specific curriculum. Although the physical environment materials and curriculum are important, the CLASS tool focuses more on the context of how teachers directly interact, engage and communicate with the children in their classroom environment. CLASS measures cooperative and creative learning experiences and focuses on the teacher’s role in allowing children to be active participants in their own learning. More specifically, CLASS promotes social justice and equity, and has “indicators” to assess how a teacher develops a sense of community and empathy for others. Not only must the teacher consider the tangible environmental elements, they must consciously incorporate quality interactions. Teachers must ask questions and engage in thoughtful conversations that emphasize back and forth dialogue rather than one and done responses. Teachers must extend the children’s vocabulary and create opportunities where children can use their expressive language skills. Lastly, teachers must provide positive feedback to children throughout the day and allow children to make choices.

Why Use the Classroom Assessment Scoring System (CLASS)

As advocates and educators, we know that engaging interactions and well-designed environments form the foundation for optimal learning to occur. High-quality preschool programs should strive to incorporate the following:

- well-managed and well-organized classrooms with clearly defined spaces

- support systems to enhance children’s social and emotional development

- a variety of instructional materials that stimulate children’s thinking and curiosity

- opportunities for authentic interactions and meaningful conversations

- a balance of teacher-directed activities and child-directed activities

- enhanced language and literacy implemented throughout the day

- opportunities for movement and classroom spaces that support kinesthetic learning

Research findings from over 3,000 classrooms found that children who were in classrooms that received higher CLASS ratings showed greater gains in social skill, language, early literacy, and math development. Furthermore, after a decade of research, crucial conclusions were made that suggest using the CLASS tool can not only improve the effectiveness of an individual classroom, it can also improve the program as well. Let’s look at some reasons as to why you might want to use the CLASS tool:

- Effective teacher–child interactions are an active and crucial ingredient for children’s social and academic development.

- Children in ECE settings are not consistently exposed to effective teacher–child interactions.

- Initial evidence suggests thresholds for effective teacher–child interactions, as measured by CLASS, in promoting children’s learning and development.

- Quality improvement efforts that focus explicitly on teacher–child interactions maximize impacts for children.

- Carefully designed and implemented professional development support can improve the quality of teacher–child interactions

The CLASS Tool

The CLASS Tool is divided into 3 Domains: Emotional Support; Classroom Organization; and Instructional Support. Each Domain has several Dimensions (see the chart below), and each Dimension has several Indicators that provide detailed descriptors of how a teacher should interact (Note: the indicators for each dimension are not listed in the chart below.)

Table 8.2: CLASS Tool Domains

|

Emotional Support |

Classroom Organization |

Instructional Support |

|

|

|

Scoring

Scoring is based on a 7-point scale, with the “low range” being a score of 1 to 2, the “middle range” a score of 3 to 5, and the “high range” a score of 6 to 7. The higher the range in each dimension the better.

CLASS Strengths

The Classroom Assessment Scoring System (CLASS) tool is a systematic observation tool that can be used to measure the interactions between teachers and their children in typical classroom settings. The CLASS tool has also been used to assess classroom quality across diverse populations, including dual language learners (DLLs), children from migrant families, tribal populations, in addition to children with special needs and children with diverse cultural backgrounds (Downer et al., 2011). The CLASS tool is deemed both reliable and valid, and it provides preschool programs and individual classroom teachers with an opportunity to regularly monitor and evaluate themselves.

Formal assessments can be made by certified CLASS evaluators and the results are shared with the teacher and program with the intent of finding strategies on how to improve interactions. The tool can also be used informally. Teachers can review each domain, dimension and indicator, and then reflect on their own practices to find ways they can incorporate more intentional interactions.

CLASS Limitations

Even though every CLASS observer is formally certified, there will be small, systematic differences in their scoring. Some observers may tend to give slightly higher scores, while others may tend to be slightly more critical. Although slight differences fall within the threshold for “reliability,” inaccurate results have been noted. One other limitation is that there is little emphasis on structural quality. More specifically, CLASS does not assess the physical environment or materials, and it is not designed to review program safety.

Additional Methods, Tools and Techniques to Ensure High-Quality Practices

Program Accreditation

Both the National Association for the Education of Young Children (NAEYC) (link: https://www.naeyc.org/) and the National Early Childhood Program Accreditation (NECPA)[13] (link: https://www.naeyc.org/accreditation) are nationally recognized agencies that set a standard of excellence for overall program quality. Programs that pursue accreditation must meet key criteria expectations in areas such as “the learning environment, teacher and child interactions, staff qualifications, professional development, and family engagement” (Center for America, 2017, p. 6). Both NAEYC and NECPA offer training, technical assistance, and consulting services to support early care and education programs that not only want to meet but exceed standard industry practices. Accreditation is a voluntary endeavor that requires programs to undergo a self-study as they prepare for the validation process. Programs that achieve accreditation status must be re-assessed every three years to demonstrate a continued commitment to high-quality practices.

The Quality Rating and Improvement System (QRIS)

The Quality Rating and Improvement System (QRIS) is a systemic approach to assess, improve, and communicate the level of quality in early care and school-age care programs.[14] The main purpose of the QRIS is to improve and standardize the quality of care in all facilities in the state, and to make childcare more accessible and affordable for families. In California, the QRIS is used to:

- Assess program quality comparably across provider types (publicly and privately funded, centers and family childcare homes) throughout the state

- Align program standards with early learning and practitioner standards

- Support continuous quality improvement for participating programs and their staff

- Provide families with information about program quality to assist them in making informed choices.[15]

The Caregiver Interaction Scale (CIS)

In the late 80’s, Arnett released the Caregiver Interaction Scale (1989) to assess a global rating of caregiver sensitivity and responsiveness in both early care and education settings and family childcare environments. The tool focuses on caregiver / teacher emotional interactions and measures several items including sensitivity, harshness, detachment, and permissiveness. Items are rated on a 4-point scale. The scale has limitations as it captures only one aspect of process quality, and thus it is suggested that additional assessments be used to measure more structural dimensions.

NAEYC Position Statement on Importance of Environmental Assessments[16]

The National Association for the Education of Young Children and the National Association of Early Childhood Specialists in State Departments of Education take the position that policy makers, the early childhood profession, and other stakeholders in young children’s lives have a shared responsibility to:

- Construct comprehensive systems of curriculum, assessment, and program evaluation guided by sound early childhood practices, effective early learning standards and program standards, and a set of core principles and values: belief in civic and democratic values; commitment to ethical behavior on behalf of children; use of important goals as guides to action; coordinated systems; support for children as individuals and members of families, cultures, and communities; partnerships with families; respect for evidence; and shared accountability.

- Implement curriculum that is thoughtfully planned, challenging, engaging, developmentally appropriate, culturally and linguistically responsive, comprehensive, and likely to promote positive outcomes for all young children.

- Make ethical, appropriate, valid, and reliable assessment a central part of all early childhood programs. To assess young children’s strengths, progress, and needs, use assessment methods that are developmentally appropriate, culturally and linguistically responsive, tied to children’s daily activities, supported by Professional development, inclusive of families, and connected to specific, beneficial purposes: (1) making sound decisions about teaching and learning, (2) identifying significant concerns that may require focused intervention for individual children, and (3) helping programs improve their educational and developmental interventions.

- Regularly engage in program evaluation guided by program goals and using varied, appropriate, conceptually and technically sound evidence to determine the extent to which programs meet the expected standards of quality and to examine intended as well as unintended results.

- Provide the support, Professional development, and other resources to allow staff in early childhood programs to implement high-quality curriculum, assessment, and program evaluation practices and to connect those practices with well-defined early learning standards and program standards.

Figure 8.3 In the right environment children thrive[17]

Conclusion

Research suggests that an enriched learning environment, along with meaningful interactions and experiences can significantly enhance a child’s overall development (Center for American Progress, 2017). Not only do children deserve high-quality learning experiences, parents need the assurance of knowing that their children are in safe, healthy and nurturing environments. Unfortunately, providing high-quality early childhood education services can be particularly challenging especially for the estimated four million children who are living in poverty and considered at-risk. Thus, the achievement gap continues to be a concern and the quest for quality is ongoing. As early childhood educators, we must strive to regularly observe, collect data and assess our programs, and reflect on our teaching practices to be more proactive in our quest for quality. While a score is important to look at and improve on, it is not the end all, be all, it merely serves to guide our practices as it relates to a whole picture. Ongoing observation and documentation help to keep us informed of how to best serve the children and families in our care.

References

Crosswalk 15 minute service suites classroom. (n.d.). U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Administration for Children and Families. Retrieved from https://eclkc.ohs.acf.hhs.gov/professional-development/article/crosswalk-15-minute-service-suites-classr

Early Childhood Mentored Field Observations by Susan Eliason is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 4.0

Hamre, B. (n.d.). Using Classroom Observation to Gauge Teacher Effectiveness: Classroom Assessment Scoring System (CLASS). Retrieved from https://cepr.harvard.edu/files/cepr/files/ncte-conference-class-hamre.pdf

Indiana Institute on Disability and Community. (n.d.). Retrieved from https://iidcweb.indiana.edu/styles/iidc/defiles/ECC/CLASS%20Overview%20for%20EEMG%20participants.pdf

Mashburn, A. (n.d.). Class: Optimizing Reliability and Validity. Retrieved fromhttps://curry.virginia.edu/faculty-research/centers-labs-projects/castl/class-optimizing-reliability-and-validity

MiraCosta College. (n.d.). Retrieved fromhttps://www.miracosta.edu/instruction/childdevelopmentcenter/downloads/5.4CLASSSummaryPreschool.pdf

Slot, P. (2018). Structural characteristics and process quality in early childhood education and care: A literature review, OECD Education Working Paper No. 176. Retrieved from http://www.oecd.org/officialdocuments/publicdisplaydocumentpdf/?cote=EDU/WKP(2018)12&docLanguage=En

Slot, P., Leseman, P., Verhagen, J., Mulder, H. (2015). Associations between structural quality aspects and process quality in Dutch early childhood education and care settings. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, Volume 33, 4th Quarter 2015, 64-76. Retrieved from https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0885200615000599

The Environment as the Third Teacher. (n.d.). Retrieved from https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED493517.pdf

University of Virginia. (n.d.). Retrieved from https://curry.virginia.edu/uploads/resourceLibrary/CASTL_practioner_Part1_single.pdf

University of Virginia. (n.d.). Retrieved from https://curry.virginia.edu/uploads/resourceLibrary/CASTL_practioner_Part4_single.pdf

University of Virginia. (n.d.). Retrieved from https://curry.virginia.edu/uploads/resourceLibrary/CASTL_practioner_Part5_single.pdf

The National Center on Early Childhood Development, Teaching and Learning. (n.d.). Understanding and Using CLASS for Program Improvement. Retrieved fromhttps://eclkc.ohs.acf.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/pdf/class-brief-understanding-using-class-program-improvement.pdf

The National Center on Quality Teaching and Learning. (2013). Improving Teacher–Child Interactions: Using the CLASS™ in Head Start Preschool Programs. Retrieved from https://eclkc.ohs.acf.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/pdf/using-the-class-in-hs-preschool-programs.pdf

Washington Office of Superintendent of Public Instruction. (n.d.). Assessment. Retrieved from

(http://www.k12.wa.us/EarlyLearning/pubdocs/assessment_print.pdf

Wechsler, M., Melnick, H., Maier, A., Bishop, J. (2016). The Building Blocks of High-Quality Early Childhood Education Programs. Learning Policy Institute. Retrieved from https://learningpolicyinstitute.org/product/building-blocks-high-quality-early-childhood-education-programs

- Espinosa, L.M. (2002). Policy Brief- High Quality Preschool: Why We Need It and What It Looks Like. Retrieved from http://nieer.org/policy-issue/policy-brief-high-quality-preschool-why-we-need-it-and-what-it-looks-like NIEER. (2002). High Quality Preschool: Why We Need It and What It Looks Like. Retrieved from: https://www.readingrockets.org/article/high-quality-preschool-why-we-need-it-and-what-it-looks ↵

- Karoly, Lynn A. and Anamarie A. Whitaker, Informing Investments in Preschool Quality and Access in Cincinnati: Evidence of Impacts and Economic Returns from National, State, and Local Preschool Programs. Santa Monica, CA: RAND Corporation, 2016. https://www.rand.org/pubs/research_reports/RR1461.html. Wechsler, M., Melnick, H., Maier, A., & Bishop, J. (2016). The Building Blocks of High-Quality Early Childhood Education Programs (policy brief). Palo Alto, CA: Learning Policy Institute. Retrieved from https://learningpolicyinstitute.org/product/building-blocks-high-quality-early-childhood-education-programs ↵

- Workman, S. and Ullrich, R. (2017). Quality 101: Identifying the Core Components of a High-Quality Early Childhood Program. Retrieved from https://cdn.americanprogress.org/content/uploads/2017/02/10063958/QualityEarlyChildhood101-brief.pdf ↵

- Department of Social Services. (n.d.). Child Care Regulations. Retrieved from https://www.cdss.ca.gov/inforesources/letters-regulations/legislation-and-regulations/community-care-licensing-regulations/child-care ↵

- NIEER. (2002). High Quality Preschool: Why We Need It and What It Looks Like. Retrieved from: https://www.readingrockets.org/article/high-quality-preschool-why-we-need-it-and-what-it-looks ↵

- Image by College of the Canyons ZTC Team is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- Wechsler, M., Melnick, H., Maier, A., & Bishop, J. (2016). The Building Blocks of High-Quality Early Childhood Education Programs(policy brief). Palo Alto, CA: Learning Policy Institute. The Building Blocks of High-Quality Early Childhood Education Programs by Marjorie Wechsler, Hanna Melnick, Anna Maier, and Joseph Bishop is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. Videos courtesy of the High-Quality Early Learning Project. ↵

- (Whitebook, Howes & Phillips, 1995).” (Retrieved on 7/10/19 https://ers.fpg.unc.edu/) ↵

- Image by College of the Canyons ZTC Team is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- Ersi. (n.d.). Related work. Retrieved from https://www.ersi.info/scales_relatedwork.html ↵

- FPG Child Development Institute. (n.d.). Environment Rating Scales. Retrieved from https://ers.fpg.unc.edu/ ↵

- Brinkman, S. et.al. (2016). The Role of Preschool Quality in Promoting Child Development. Retrieved from https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/bitstream/handle/10986/23629/The0role0of0pr0from0rural0Indonesia.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y ↵

- NECPA. (2019). National Early Childhood Program Accreditation. Retrieved from https://necpa.net/ ↵

- Quality Rating and Improvement System by CDE is used with permission. ↵

- Quality Rating and Improvement System by CDE is used with permission. ↵

- Source: (http://www.k12.wa.us/EarlyLearning/pubdocs/assessment_print.pdf ) ©2008 Washington State Office of Superintendent of Public Instruction. This document may be freely reproduced without permission for non-profit, educational purposes. Use of or reference to this document should cite: A Guide Assessment in Early Childhood; Infancy to Age Eight. Washington State Office of Superintendent of Public Instruction, 2008. ↵

- Image by Divine Cox is in the public domain. ↵