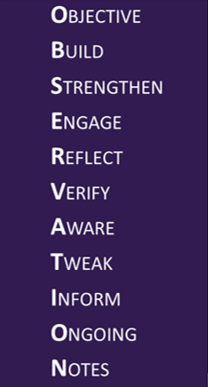

Chapter 7: Observation and Documentation: The Key to Intentional Teaching

Gina Peterson and Emily Elam

Chapter Objectives

In this chapter, you will be learning about:

- The Role of Observation

- Becoming a Skilled Observer

- Observations can be Spontaneous or Planned

- The Role of Documentation

- Objective Versus Subjective Observation Evidence

- Recognizing Your Own Biases

- Ethical Practices When Observing Children

- Observation Dos and Don’ts

Introduction

To provide children with a safe and nurturing learning environment and to maintain program effectiveness, teachers must incorporate observation, documentation and assessment into their daily routines. To truly be effective, teachers must develop skills and strategies that are grounded in best practices. In this chapter you will be presented with information that highlights how observation and documentation can be used as a key strategy to ensure intentional teaching. You will examine the initial steps to take to becoming a skilled observer, and you will reflect on how to objectively document the interactions that you see and the conversations that you hear. It is important to note that becoming a skilled observer takes time and practice, and that learning how to incorporate observation, documentation and assessment into your regular routines and daily duties requires some thoughtful consideration.

The Role of Observation

Observations are conducted every day in early childhood classroom environments. Teachers are constantly surveying the environment and completing safety checks to make sure the equipment and materials are safe for the children to use. Teachers also perform daily health screenings to ensure their children are healthy enough to participate in program activities. Beyond the standard safety check and health screening, teachers have many other important tasks and duties that they must do in order to maintain a copasetic classroom environment. Intentional teachers use their observations to plan and implement curriculum, set up engaging learning environments, monitor the children’s social interactions, track behaviors, communicate with families, and assess each child’s progress and development. Essentially, observations help teachers be more accountable. By conducting regular observations intentional teachers can:

- Evaluate program effectiveness

- Evaluate teacher effectiveness

- Make improvements to ensure quality practices

- Plan and implement developmentally appropriate curriculum

- Measure and assess a child’s development

- Develop respectful family partnerships

- Understand the cultural practices and family structure

- Select effective learning strategies to support and accommodate the diverse needs of children

- Ensure ethical conduct and professional standards of practice

- Teach with confidence

Figure 7.1: COC OER[1]

|

|

Pin It! Observation Observation is defined as “the process of gathering information about objects and events using senses of sight, smell, sound, touch and taste, noticing specific details or phenomena that ordinarily might be overlooked” (CDE, 2016 p. 64).[2] |

If we want to understand children, we must first watch them and listen to them. Then, we must try to make sense of what we observed and give it meaning. The role of observation is to provide teachers with information and evidence that they will need to make informed decisions on how to best support the children in their care. With each observation, you will get a glimpse into a child’s developing mind. Not only will you see a child’s personality emerge, you will be able to see what a child can do. As you watch your children, you will see how they problem solve when conflicts arise and how they cope with the stress from being in a group setting. You will learn about their individual needs and their cultural practices. When you watch children closely, their interests and abilities are revealed. With each observation, you will gain useful insight that will help you become an intentional teacher.

Becoming a Skilled Observer

To truly observe a child, you must be present, knowledgeable, inquisitive and intentional. With every observation, you will sharpen your skills as you learn how to effectively gather objective evidence and detailed data.

Be present: To capture all the individual mannerisms, subtle social nuances, non-verbal body language and dynamic conversations that occur throughout the day you must be attentive, focused and ready to go at any given moment. Children move fast. When we blink, we are bound to miss some little detail or precious moment, that’s a given. Being present takes considerable effort and careful planning.

Be knowledgeable: Understanding the core concepts of early childhood education is extremely important if you are to set reasonable expectations and plan developmentally appropriate learning experiences. Familiarizing yourself with child development theories will help you understand and appreciate why children do what they do. Learning about the key principles in early care and education will provide you with a solid foundation and a wide range of instructional strategies to support a child’s development.

Be inquisitive: Think of yourself as a researcher. Your primary mission is to investigate the children in your care by routinely gathering evidence, using a variety of observation methods and tools. As a good researcher you will need to ask some thoughtful questions. These questions will guide you as you plan purposeful observations and as you select your method of observation. Here are some sample questions you may ask yourself: What activities interest Max? How many times did Stevie hit today? What skills did Hazel master today with this activity, and what skills need further support? How long did Zoey stay engaged while playing in the sandbox? What milestones will this activity support? By asking thoughtful questions, you will learn more about the children in your care and you will do a better job at supporting each child’s individual needs. Rather than fixating on a child’s behavior, in time you will begin using focused observations to try and figure out the reasons why a child acts the way they do.

Be intentional: As you organize learning experiences, set up the classroom and outside environment, assess children’s developmental progress, engage in activities, and interact with your children and families – you must have a thoughtful plan of action in place. “Intentional teaching means that everything you do as a teacher has a specific goal and purpose” (Gordon & Browne, 2016 p. 103). Even as spontaneous situations arise, intentional teachers must make the most of teachable moments. Intentional teachers conduct regular observations and gather objective documentation data to be accountable for the actions they take, the plans they generate and the assessments they make.

Observations can be Spontaneous or Planned

Spontaneous observations occur all the time. Whether teachers are actively engaged with their children during an activity or in the background cleaning up after an activity, teachers have numerous opportunities to see and hear some wonderful developments as they randomly occur. According to Piaget, children require long uninterrupted periods of play and exploration so that they can discover things for themselves. If we truly believe that children are capable of socializing, problem solving, and creating complex systems with rules, then we can successfully use spontaneous observations to capture a child’s development as it unfolds naturally.

As intentional teachers, we can also appreciate when teachable moments arise unexpectedly. These golden moments are noteworthy as well. For example, as we witness a child attempting to master a milestone, we may provide some verbal support or guidance to scaffold the child’s learning. For example, when Abraham is becoming frustrated with not being able to get a piece of his puzzle to fit, a teacher might ask, “What happens when you turn the piece around?” During spontaneous situations, we must remember to simultaneously make mental notes so that we can later write down and reflect on a more formal plan of action that can be later used to help the child achieve their developmental goals.

Let’s review the advantages and disadvantages associated with spontaneous observations.

Advantages: Being in the moment allows you to enjoy your children, and children appreciate your presence. When you are present, you can celebrate a child’s success or provide positive reinforcements to help them master major milestones. While being spontaneous, you can focus on the child’s interests and pose thoughtful questions to extend and enrich their learning experience. When a teacher keeps a low profile, a child is less likely to be self-conscious or nervous.

Disadvantages: The longer you wait to document your spontaneous observation evidence, the harder it will be to remain objective and recall the vital details which is important when tracking behaviors or assessing development. Also, the more time that passes, the more difficult it will be to access accurate data. For example, by not documenting the children’s dialogue or capturing their key quotes in a timely manner, you may find it difficult to remember their actual word choices and use of vocabulary which is essential for assessing a child’s expressive language development.

Let’s now discuss focused or planned observations. Becoming a skilled observer takes practice. At first you may be slightly overwhelmed with trying to incorporate an official observation time into your already busy schedule. You may struggle with finding that delicate balance between knowing when to interact with your children and realizing when to step back and observe. Once you do observe, you might be surprised by the amount of evidence you have collected on each child. What’s more, you will have to sift through all the evidence, and that can be both time consuming and exhausting. Since your time is limited and you cannot possibly observe everything, incorporating a planned observation will help you navigate through your busy day and you will be able to gather more specific evidence (Grouland & James, 2013).

Questions you may want to ask yourself as you plan your next observation

When should I observe?

From the moment a child walks into their classroom until the time they leave, opportunities to learn are occurring. Some observations will happen spontaneously, while others will be scheduled. To see a child’s full potential, you will need to observe at various times throughout the day. For example, some children are slow-to-warm and it may take them some time to get acclimated before they can fully engage and interact with others. If a child is slow -to-warm, the morning drop-off may not be the best time to document their social development. You will want to track them throughout the day, at various times (including transition times and snack/meal times), to get a full picture of who they are and what they can do.

Where should I observe?

Many times, observations are centered around structured, teacher-directed activities. This is, in fact, a perfect time to witness what major milestones a child has mastered. However, observing a child while they are exploring in the dramatic play area (inside) or while they are in the sandbox area (outside) can prove to be just as enlightening. During child-directed play or open exploration, you will no doubt be able to document many of the developmental skills as suggested in the DRDP or Rating Scales, especially how they communicate, cooperate, solve dilemmas and create. Because children can play and learn differently while they are inside as compared to when they are outside, it is necessary to observe in both environments. Likewise, it is important to observe in all activity areas and play spaces.

What observation method should I use?

Use a variety of methods to record and document your children. You will want to “try out” several tools and techniques to find your “go to” method. Because each tool has a specific purpose or focus, using a variety of methods will provide you with sound documentation data to better understand the whole child’s development. Note: In the next chapter, you will examine the various tools and techniques more closely.

Who should I observe?

You will want to observe each child as individuals, and you will want to track group interactions. Becoming aware of who is in your class is necessary if you are going to create a caring classroom community and respectful learning environment. Look for those who are the leaders in your group; find out who needs more one-to-one support and who are your helpers; watch for who plays with who. This insight can help you organize peer scaffolding opportunities which can free up some of your time. As a gentle reminder, sometimes we connect with certain children for one reason or another, and other times a child may challenge us. Either way we need to regularly observe each child with an open mind and an open heart, and we need to look at children with a clear lens that is free of bias. Each child needs your attention; each child has unique gifts; and each child needs your support.

What is the focus of my observation, what am I looking for?

With focused observations, there usually is a specific goal in mind. For example, you might want to know what milestones a child has mastered. For that, you would use a developmental checklist to “check-off” all the skills the child was observed doing. Maybe you want to learn what the child’s interests are and what they like to play with. For that, you can use a frequency count to tally up all the areas and activities the child used during that observation. Keep in mind that you can observe several skills and competencies across multiple domains during one observation. For example, one day you might set out a math activity and the children are expected to create patterns using colorful beads and pipe cleaners, While they work and play, you can listen to the children’s conversations as they describe the patterns they are making; and you can note their fine motor development based on how well they string the beads onto the pipe cleaner; you can also see how they shared space and materials with their peers. Although this was a math activity, many other areas of development can be observed.

The Role of Documentation

One of the cornerstones of a high-quality early care and education program is the practice of observing, documenting and assessing children’s development. According to NAEYC (2009), in order to make formative decisions that will guide what goes on in the classroom, there needs to be an organized system in place to collect information. When we record our observations and collect data, we “hold in memory the actions, nonverbal communication, or comments that seem to be significant to children’s thinking” (California Preschool Program Guidelines, 2015 p. 46). When we document children’s learning and collect key artifacts, we create tangible evidence that we can share with the children and their families, along with administrators and stakeholders. There are many ways you can record and document children’s learning. In fact, you should attempt to utilize several methods as part of your regular observation routines.

To collect and record data you can use the following methods:

- running records

- anecdotal notes

- checklists

- frequency counts

- learning stories

- time or event samples

- work samples

- taking photos, videotaping, or audio recordings

To store your documentation

To safely store your collected data, you will need to have an organized system in place. Portfolios are a popular strategy used by intentional teachers. To create a portfolio, you can use a binder or notebook, a file or accordion-style folder, or a cardboard box. As you collect observation evidence for each child, it is vital that you date everything so you can organize it chronologically. This will help you track each child’s progress throughout the school year more efficiently. Portfolios help you construct a well-rounded and authentic picture of each child in your class. Knowing the “whole child” you are better equipped to build on each child’s individual interests, and you are more apt to plan developmentally appropriate activities.

Each child should have their own portfolio. A well-organized portfolio will contain observations and artifacts of children’s work that are collected at different time periods throughout the school year. It is recommended that you include some type of documentation that highlights each developmental domain. For example:

- Gross Motor: Take photographs of your child while they are engaged in outside activities like running, jumping, climbing, riding a bike or playing in the sandbox.

- Fine Motor: Keep a checklist of when your child learns to button, zip, and tie his shoes. Include work samples of their cutting, coloring, painting, and samples of emergent writing

- Social-Emotional: Write anecdotal notes when your child engages in open-ended, child-directed play. Take note of how they share and cooperate with others. Do a frequency count to see which centers your child chooses to spend their time in and tally their play patterns to see if they prefer to play alone or with others.

- Cognitive: Chart a science experiment and take photos. Photograph a completed puzzle. Use a video camera to record a child as she builds a block bridge. And, as she explains her process and she had to figure out all the steps to take so that the bridge wouldn’t fall down – be sure to record that too.

- Literacy and Oral language: Save writing examples to track how the child writes her name. Include illustrations of stories they love and the stories they write themselves. Write down quotes in your running record or make audiotapes of conversations during circle time.

- Creative expression: Videotape your child while playing in the dramatic play area or while performing a dance during music and movement. Photograph a clay creation, painting or block tower.

To be clear, it isn’t the amount of documentation you collect for each portfolio that matters, it’s the quality of information you gather. Portfolios tell a story of the whole child. There should be a beginning, middle, and an end. Each work sample, anecdotal note, checklist, frequency count and learning story should be used to showcase how a child processes information, develops relationships, and learns while playing.

To document children’s learning

Whether you collect evidence through spontaneous or planned observations, you will use your documentation to ultimately assess a child’s learning, growth, and development. With well-organized documentation, intentional teachers can effectively communicate with a child’s family, using the evidence and artifacts they have collected over time. Families appreciate being able to see their child’s progression and how they interact with others. Families also enjoy seeing the types of activities their child engages in during a typical day at school. Here are a few ways documentation can be used to showcase a child’s learning, growth and development:

- rating scales and formal developmental assessments

- daily progress reports

- documentation boards

|

|

Pin It! 10 Teacher Tips When Gathering your Documentation

|

Objective versus Subjective Observation Evidence

Intentional teachers must learn how to write objective observations. As you observe, it is best to write down all that you see and hear, and report just the facts. It takes practice to learn how to separate facts from opinions. Here are some helpful tips for you to review:

Table 7.1: Objective Observations vs. Subjective Observations

|

Objective Observations |

Subjective Observations |

|

Objective observations are based on what we observed using our senses, we record exactly what we see, hear, taste, touch, and smell |

Subjective observations are often influenced by our past events, personal experiences and opinions, and can be biased based on our cultural backgrounds |

|

Objective information is based on the facts we gather. If we don’t see it, we don’t report it. We report only details and provide vivid descriptions |

Subjective information is based on our opinions, assumptions, personal beliefs, prejudice feelings or can be based on suspicions, rumors and guesses |

|

Results are more likely to be valid and reliable from child to child |

Results are often inconsistent and vary from child to child |

|

Objective Terms that can be Used: Seems to be; Appears to |

Subjective Words to Avoid: Just; because; but; always, never; can’t; I think; happy, smart, helpful, pretty, angry, shy, likes, loves, hates, sad |

Recognizing Your Biases

Google the word bias and this is what pops up: “prejudice in favor of or against one thing, person, or group compared with another, usually in a way considered to be unfair.”

Biases, we all have them. Biases stem from our upbringing. Every interaction and every experience we have had has shaped who we are. To some degree, our biases influence our beliefs and behaviors, they sway our attitudes, and they affect our personalities. Because our biases are so ingrained into who we are, it would be unrealistic to simply say “ignore your bias.” Therefore, a valuable exercise might be to do a self-check and examine your own biases. Look for those biases that are “triggers.” More specifically, think about the behaviors, temperamental traits, and moods that make you feel uncomfortable, frustrated, or annoyed.

It is important to note, that we might not be fully aware of all our biases. For example, when a child says, “give me some milk!” Our first response might be “Ummm, how do you ask?” We might not realize that manners (or lack of them) can make us react in a judgmental way. What’s important to recognize is that how we feel about the child’s behavior can taint how we see them. What’s more, our biases can influence how we gather our observation evidence. As intentional teachers we have to recognize our biases so we can treat all children with the respect that they deserve. According to NAEYC’s Code of Ethical Conduct and Statement of Commitment (2011),

P-1.3—We shall not participate in practices that discriminate against children by denying benefits, giving special advantages, or excluding them from programs or activities on the basis of their sex, race, national origin, immigration status, preferred home language, religious beliefs, medical condition, disability, or the marital status/family structure, sexual orientation, or religious beliefs or other affiliations of their families (p. 3).

So as not to lose our objectivity, it is important to keep an open heart, an open mind, and a clear lens. Rather than letting a child’s behavior trigger you, look beyond their behavior, look beyond your bias. Focus on collecting objective observation evidence and use that data to reflect on what might be causing that behavior. Consider ways that you can support the child through redirection, modeling, scaffolding or positive reinforcements. As intentional teachers, one of our primary roles is to empower children, and to build meaningful relationships by creating warm, caring environments (Epstein, 2007).

|

|

Pin It! Common Mistakes to Avoid When Writing Observation Evidence

|

Ethical Guidelines when Observing Children

Every day, teachers observe, record and capture essential moments in a child’s development. The evidence and artifacts that are gathered are then used to plan curriculum and assess development. Although we have highlighted the importance of gathering work samples and observation evidence as a key element to be an intentional teacher, we must also consider the perspective of the child. In the article “Who is Watching? Thinking Ethically about Observing Children” the authors highlight some of the ethical tensions that can arise within early childhood settings when trying to balance the rights of children, the responsibilities of teachers and the role of a student who is training to be a future teacher.

In most classrooms, a typical day includes teachers grabbing their cameras to take snapshots of the children in their care so that they will have ample documentation. Consider this – does the teacher’s presence change the context of the child’s experience? Does the thought of being monitored make the child behave any differently? How does the child feel about having their picture taken? Are teachers becoming overly concerned about capturing children in precious moments, rather than being engaged in teachable moments? As a “student” who is learning to observe and document a child’s development it is important for you to consider the following guidelines when observing children:

- Take every precaution to maintain confidentiality and to ensure privacy

- Remember to ask if it is OK to take photographs of children and their work

- Understand that children have the right not to take part in activities

- Be respectful and keep a reasonable amount of space between you and the child so as not to interfere with their play and learning

- Be attuned to children’s body language, temperament and styles of communication

- See each child as a unique individual who has their own perspective, set of feelings, interests, and way of socializing, along with their own cultural context, belief system, and values

- Be upfront and inform children about the purpose of your observation visit if you are approached

- Share information with the child about what you have observed when appropriate

- Write quotes down just as they were said without adding context, or trying to rationalize what the child may have meant

- Be aware that photos and observation data should be collected in a non-intrusive manner

- Ensure that observation evidence and photos are used only for the purposes intended

- Handle photos and data with care and sensitivity, and always store information securely

- Realize that a child’s reactions, behaviors and conversations may not be what you expect and therefore you should refrain from being judgmental or tainted by your cultural biases

By following these guidelines, you are providing the children you observe with the respect they deserve while ensuring their dignity and safety. The centers and programs where you are observing are trusting you to act with integrity while you are at their site observing their children. Lastly, families will appreciate that you have their child’s best interest at heart.

Figure 7.2 Observing the world through a different lens[3]

Observation and Documentation Dos and Don’ts

Whether performing a planned or spontaneous observation here are some helpful tips to ensure you are recording quality evidence:

Table 7.2: Observation and Documentation Do’s and Don’ts

|

Observation and Documentation DOs: |

Observation and Documentation DON’Ts |

|

|

Conclusion

To become a skilled observer takes time and practice (Gronlund & James, 2013). You will need to figure out your rhythm so that you can incorporate observation and documentation into your regular routine. As an intentional teacher, you will want to plan systematic observations so that you can document each child’s unique qualities, interests, developmental strengths and needs, as well as uncover their cultural practices, approaches to learning and play preferences throughout the school year. As you gather evidence you will want to be as objective as you can be, and you will have to recognize your biases. As you collect your documentation on each child, you will want to organize it in a chronological manner and store it safely. Lastly, be sure to observe every child in your class, be aware that some children may catch your attention more than others for one reason or another. In the next chapter, we will examine several observation tools and techniques that you will want to use as part of your regular observation routine to ensure high-quality practices.

References

California Department of Education. (2016). The Integrated Nature of Learning. Retrieved from https://www.cde.ca.gov/sp/cd/re/documents/intnatureoflearning2016.pdf

Early Childhood Videos. (2016, Aug 12). Documenting Children’s Learning. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=RdOqkukZikE

First 5 California. (2015). For the Record: Documenting Young Children’s Learning and Development. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-WAy474XE6s

janiceaughey. (2011). Subjective-Objective Exercise. Retrieved from https://www.slideshare.net/janiceaughey/subjective-objective-exercise

JECEI. (n.d.). The Importance of Documentation. Retrieved from http://www.jecei.org/PDF/10%20The%20Importance%20of%20Documentation%20and%20Project%20Work.pdf

Lynn Cohen. (2020). The Power of Portfolios. Retrieved from https://www.scholastic.com/teachers/articles/teaching-content/power-portfolios/

Mehan, S., & Moore, L. (n.d.). Who is watching? Thinking ethically about observing children. Early Childhood Australia. Retrieved from http://www.earlychildhoodaustralia.org.au/our-publications/every-child-magazine/every-child-index/every-child-vol-17-3-2011/watching-thinking-ethically-observing-children-free-article/

Posada, Margarita M. (2004) Ethical Issues in Assessments with Infants and Children. Graduate Student Journal of Psychology, Vol. 6, 42-47. Retrieved from https://www.tc.columbia.edu/publications/gsjp/gsjp-volumes-archive/gsjp-volume-6-2004/755_Assessment-finalversion.pdf

Sage Publications (n.d.). Observation and Assessment. 86-110. Retrieved from https://www.sagepub.com/sites/default/files/upm-binaries/9656_022816Ch5.pdf

Seitz, H. (2008). The Power of Documentation in the Early Childhood Classroom. Young Children, 88-93. Retrieved from https://www.naeyc.org/sites/default/files/globally-shared/downloads/PDFs/resources/pubs/seitz.pdf

- Image by College of the Canyons ZTC Team is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- The Integrated Nature of Learning by the CDE is used with permission ↵

- Image by Andrew Seaman on Unsplash ↵