9.4 Anatomical, Physiological, and Psychological Changes During Pregnancy

Body System Changes During Pregnancy

Nurses assess pregnant women and analyze assessment data for expected versus unexpected findings that require follow-up. Nurses must understand the anatomical, physiological, and psychological changes that commonly occur during pregnancy to provide health teaching to pregnant women and their partners to help them adapt to the expected changes and recognize any unexpected changes that may place the pregnancy at risk. Table 9.4a summarizes expected body system changes and associated symptoms during pregnancy. These changes are further discussed in the following subsections.

Table 9.4a. Expected Body System Changes and Associated Symptoms During Pregnancy[1]

| System | Changes During Pregnancy |

|---|---|

| Reproductive |

|

| Cardiovascular |

|

| Respiratory |

|

| Hematological |

|

| Gastrointestinal |

|

| Urinary and Renal |

|

| Integumentary |

|

| Musculoskeletal |

|

| Nervous |

|

| Immune |

|

| Endocrine |

|

Reproductive System Changes During Pregnancy

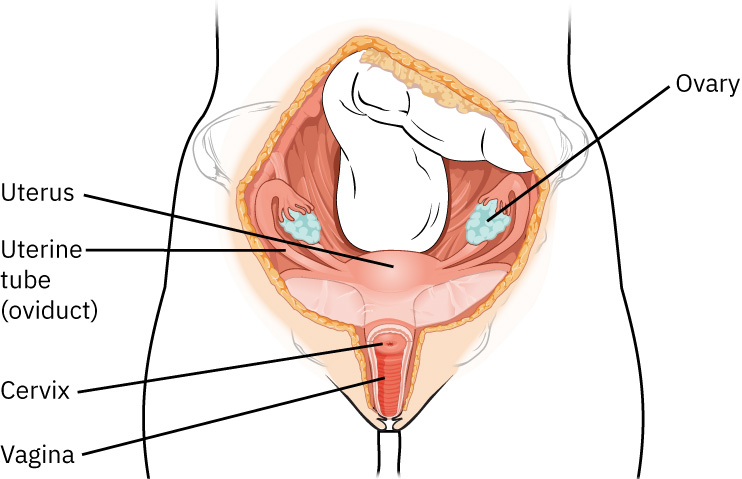

Many significant changes occur in the reproductive system during pregnancy. The uterus expands to accommodate the growing fetus, amniotic fluid, and placenta. Changes in the vagina and cervix allow for passage of the fetus into the extrauterine environment. The ovaries assist in maintaining the pregnancy until the placenta takes over. The breasts prepare for lactation.[2] See Figure 9.3[3] for an illustration of the female reproductive system.

Uterus

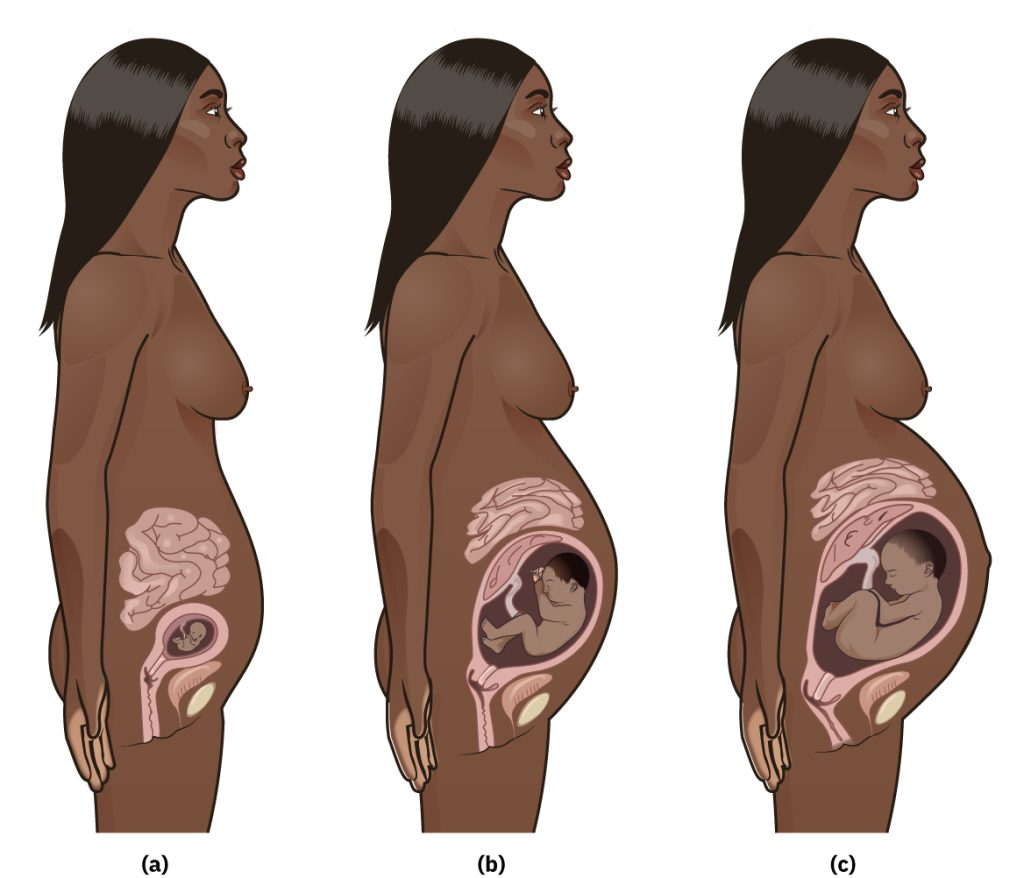

The uterus is a unique organ because it can enlarge (via hyperplasia and hypertrophy) without increasing the number of its cells. Initial uterine enlargement is stimulated by estrogen. The myometrial cells in the walls of the uterus stretch and thin as the fetus grows, the placenta enlarges, and the amniotic fluid increases. The uterine blood vessels enlarge as well, increasing the blood volume supporting the pregnancy, with the majority of the blood flow going to the placenta. The nonpregnant uterus weighs about 60 grams, enlarging to 1,000 to 1,200 grams at 40 weeks of pregnancy. The fundus (i.e., topmost portion) of the enlarging uterus is at the symphysis pubis by 12 weeks of gestation and reaches its highest point at the xiphoid process around 36 weeks of gestation. At the end of the pregnancy, the enlarged uterus has displaced the intestines, changed the shape of the rib cage, shifted the lungs, and changed the pregnant woman’s center of gravity The enlargement also leads to hypercontractility of the uterus, resulting in spontaneous, irregular, and mild uterine contractions known as Braxton-Hicks contractions that occur throughout the pregnancy. Braxton-Hicks contractions normally have no effect on the cervix until the final weeks of the pregnancy when the cervix begins to soften in preparation for labor.[4] See Figure 9.4[5] for an image of pregnancy progression as the uterus enlarges.

Cervix

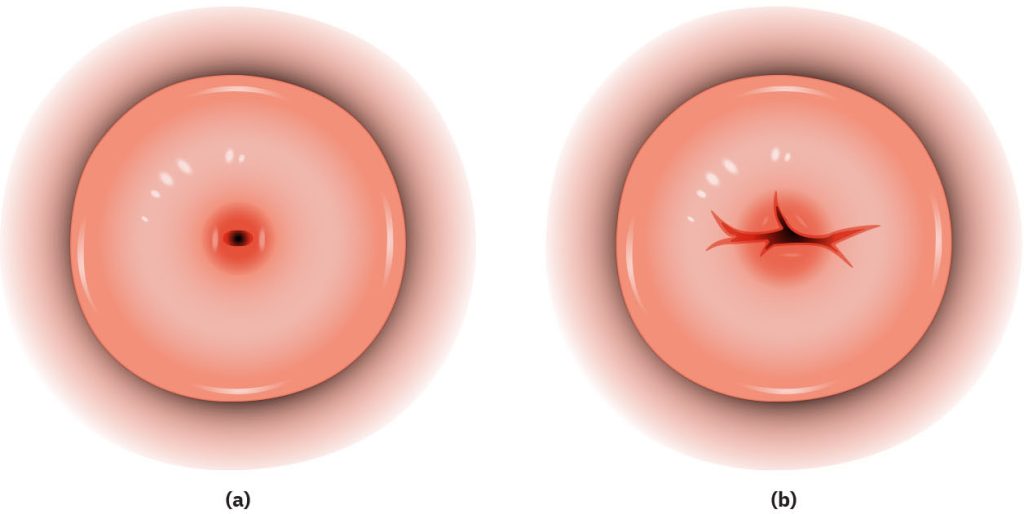

The cervix is the lower, narrow portion of the uterus that connects the uterus to the vagina. It is a gateway between these two structures and plays a crucial role in reproductive physiology. In a nonpregnant woman, the cervix is firm and closed and prevents bacteria from ascending into the uterus and causing infection. During nonfertile times, cervical mucus is thick and inhibits the transit of sperm into the uterus. During fertile times, cervical mucus is thin and slippery, facilitating the passage of sperm. Estrogen-induced changes in the cervix during pregnancy cause endocervical glands to secrete thick, tenacious mucus that accumulates and forms a mucous plug. The mucous plug seals the cervical canal and prevents ascent of bacteria into the uterus. When cervical dilation begins during labor, the mucus plug is expelled. The cervical os is a small opening in the middle of the cervix that can be visualized and palpated during physical examination. The cervical os of a woman who has never been pregnant or is pregnant for the first time is round and small, but the cervical os of a woman who has had one or more previous pregnancies will appear like a slit. See Figure 9.5[6] for an illustration of the cervical os.

Ovaries

The ovaries stop releasing ova during pregnancy, and human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG) produced by the fertilized egg maintains the corpus luteum. The corpus luteum forms from the remnants of the ovarian follicle and secretes progesterone until mid-pregnancy when the placenta begins to produce progesterone to help sustain the pregnancy to full term. The increased estrogen and progesterone levels during pregnancy prevent ovulation by blocking secretion of follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) and luteinizing hormone (LH).[7]

Vagina

Estrogen-induced changes during pregnancy cause increased vascularization, hyperplasia, and hypertrophy of the vagina. Additionally, vaginal secretions become thicker, white, and more acidic and contribute to the creation of the mucous plug. This environment helps prevent bacterial infections but can contribute to an increase in yeast infections during pregnancy. By 40 weeks’ gestation, the vaginal wall becomes relaxed to permit distention and passage of the infant.[8]

Breasts

The breasts increase in size during pregnancy due to glandular hyperplasia caused by increased estrogen and progesterone levels in preparation for lactation. Increased pigmentation of the areola and striae may develop as pregnancy progresses. Colostrum, an antibody-rich secretion that helps develop the newborn’s immunity, may be expressed from the breasts by the sixteenth week of pregnancy.[9]

Cardiovascular System Changes During Pregnancy

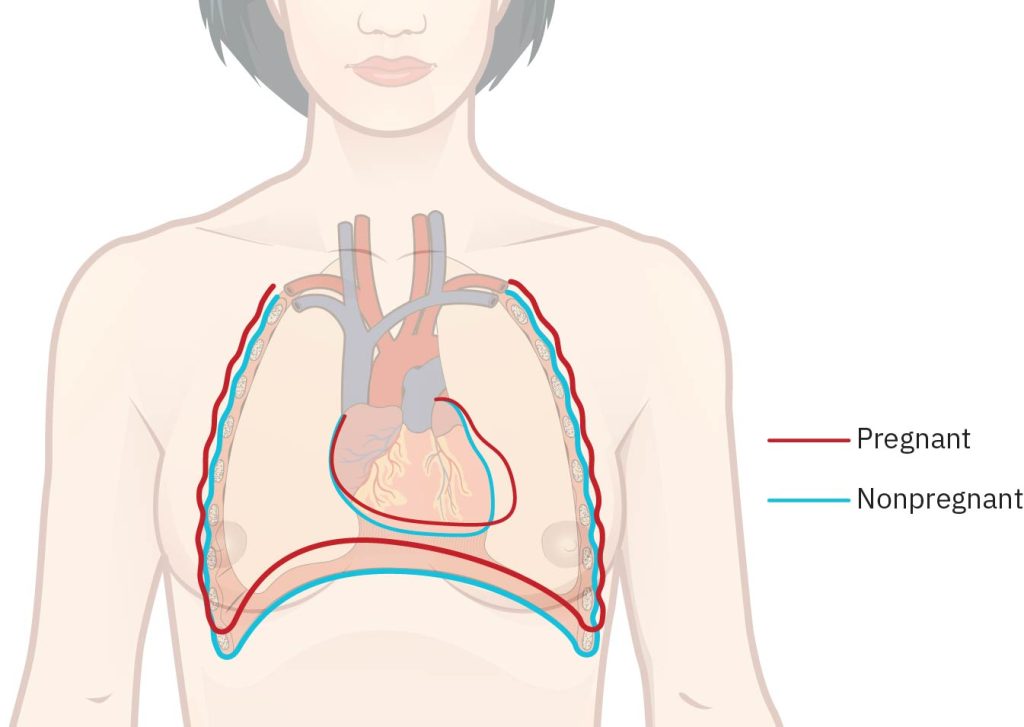

The heart is pushed up and to the left by the enlarging uterus, and a systolic heart murmur may be heard in approximately 90% of pregnant women. Throughout the pregnancy, blood volume and cardiac output increase by 30-45% above nonpregnant levels. The heart rate mildly increases approximately 10-15 beats per minute to 70-115 beats compared to the normal range of 60-100 beats per minute. Peripheral vascular resistance decreases, and blood pressure typically decreases slightly during the second trimester, with a gradual return to pre-pregnancy baseline levels by the end of the third trimester. Dizziness may occur due to changing blood volume and blood pressure during pregnancy.[10] See Figure 9.6[11] for an illustration of heart and diaphragm displacement in the mother during pregnancy.

The weight of the uterus on the vascular system causes fluid pooling and edema in the lower extremities, especially during the second half of the pregnancy. In the last weeks of pregnancy, the supine position should be avoided in pregnant women for prolonged periods of time because the heavy uterus puts pressure on the superior vena cava and restricts blood return to the heart. The restricted blood return causes hypotension in the mother and reduces blood flow to the fetus via the placenta. When the pregnant woman lies on her side, the venous return is more efficient, the fluid pooling and edema are relieved, and potential fetal risks are avoided.[12]

Respiratory System Changes During Pregnancy

Respirations are normally between 12 and 22 breaths/minute. The diaphragm becomes elevated as a result of the pressure from the enlarging uterus, resulting in a change from abdominal breathing to thoracic breathing. The chest circumference may increase as much as six centimeters. In addition to these changes, the client may experience nasal stuffiness, congestion, or epistaxis (nose bleeds) due to estrogen-induced edema and vascular congestion of the nasal mucosa.[13]

Oxygen consumption during pregnancy increases to meet the needs of the mother, fetus, and placenta. Hyperventilation during pregnancy is caused by an increased tidal volume (the amount of air that moves into and out of the lungs during each breath) due to the increased oxygen needs. This can cause mild respiratory alkalosis and may be perceived by the client as shortness of breath.

Review information on respiratory alkalosis in the “Acid-Base Balance” section of the “Fluids and Electrolytes” chapter of Open RN Nursing Fundamentals, 2e.

Hematologic System Changes During Pregnancy

Physical changes that occur to the hematologic system during pregnancy include an increase in the red blood cells and plasma levels. An increase in red blood cells is needed for the transport of additional oxygen. The plasma volume increases by 50%, which can cause hemodilution and physiologic anemia of pregnancy due to the ratio of plasma volume to the number of red blood cells, resulting in decreased hematocrit levels. An increase in the ability of the blood to coagulate, or hypercoagulability, occurs during pregnancy to prepare for normal blood loss during the birthing process. Plasma fibrin increases 40 percent, and fibrinogen increases 50 percent. The platelet count falls slightly because of hemodilution during pregnancy. The increase in blood coagulability, along with blood pooling from the weight of the uterus on the lower extremities, places the pregnant woman at risk for venous thrombus formation. White blood cell production also increases during pregnancy due to the stimulating effects of estrogen and cortisol on the bone marrow to produce more WBCs. See Table 9.4b for hematological reference ranges for nonpregnant women compared to first trimester (first day of LMP-Week 13 and 6 days), second trimester (Week 14-Week 27 and 6 days), and third trimester (Week 28 – Week 40 and 6 days) ranges.

Table 9.4b. Normal Hematological Reference Ranges for Women

| Hematologic Lab Test | Nonpregnant | First Trimester | Second Trimester | Third Trimester |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hemoglobin (g/dL) | 12–16 | 11.6–13.9 | 9.7–14.5 | 9.5–14.5 |

| Hematocrit (%) | 36–48 | 31.0–41.0 | 30.0–39.0 | 28.0–40.0 |

| WBC (×106/mm3) | 4.5–11 | 5.7–13.6 | 5.6–14.8 | 5.9–16.9 |

| Platelet count (×109/L) | 150–450 | 174–391 | 155–409 | 146–429 |

| PT (sec) | 11–13.5 | 9.7–13.5 | 9.5–13.4 | 9.6–12.9 |

| aPTT (sec) | 25–35 | 24.3–38.9 | 24.2–38.1 | 24.7–35.0 |

| Fibrinogen (mg/dL) | 200–400 | 244–510 | 291–538 | 373–619 |

Gastrointestinal System Changes During Pregnancy

During the pregnancy, gastrointestinal system changes occur due to displacement of the intestines due to the growth of the fetus and uterus, as well as hormonal changes. See Figure 9.7[14] for an illustration of displacement of the intestines during pregnancy. The pregnant woman may experience feelings of nausea and vomiting, which typically take place in the first trimester as a result of the increased hCG secretion and changes in carbohydrate metabolism. Additionally, the client may experience an increase in heartburn due to the pressure of the enlarging uterus, elevation of progesterone levels causing relaxation of the smooth muscle, the displacement of the intestines laterally, the displacement of the stomach superiorly, and the reflux of acidic secretions due to a relaxation of the lower esophageal sphincter. Bleeding gums may occur due to increased circulating estrogen, so regular dental care is important. Hemorrhoids often occur due to constipation and increased pressure of blood vessels below the uterus. Decreased gallbladder emptying during pregnancy due to slowed gastrointestinal motility can cause a retention of bile salts, leading to intense itching starting with the palms of the hands and the soles of the feet. This intense itching can be a sign of a serious disorder called cholestasis of pregnancy. Cholestasis of pregnancy requires medication and/or delivery of the baby at 37 weeks. There are no long-term sequelae for the pregnant women, but cholestasis of pregnancy can cause sudden fetal death.[15],[16]

Urinary and Renal System Changes During Pregnancy

The growing fetus puts pressure on the mother’s bladder, causing urinary frequency. Bladder tone decreases, and capacity increases because of the rise in progesterone in pregnancy. These changes can impair full emptying of the bladder, increasing the risk for urinary tract infection. The kidneys and ureter can become dilated, typically on the right side due to the lie of the uterus, which can also cause urinary stasis and increased risk for infection. The glomerular filtration rate (GFR) rises, along with an increase in urine volume during pregnancy. More solutes are filtered during pregnancy because the kidneys are now filtering waste products from both the pregnant woman and the fetus. The increase in filtration of solutes overwhelms tubular reabsorption, and low levels of glucose and protein are excreted in the urine. This elevated urine glucose must be differentiated from elevated blood glucose levels that occur with gestational diabetes. The change in the GFR also speeds up the excretion of drugs, and dosage adjustments must be made to prescribed medications that are metabolized by the kidneys.[17] See Table 9.4c for a summary of renal function normal reference ranges.

Table 9.4c. Renal Function Normal Reference Ranges in Women[18]

| Lab Test | Nonpregnant | First Trimester | Second Trimester | Third Trimester |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| BUN (mg/dL) | 7–20 | 7–12 | 3–13 | 3–11 |

| Serum creatinine (mg/dL) | 0.6–1.1 | 0.4–0.7 | 0.4–0.8 | 0.4–0.9 |

| GFR (mL/min) | 90–120 | 131–166 | 135–170 | 117–182 |

| Serum protein (g/dL) | 6–8 | 6.2–7.6 | 5.7–6.9 | 5.6–6.7 |

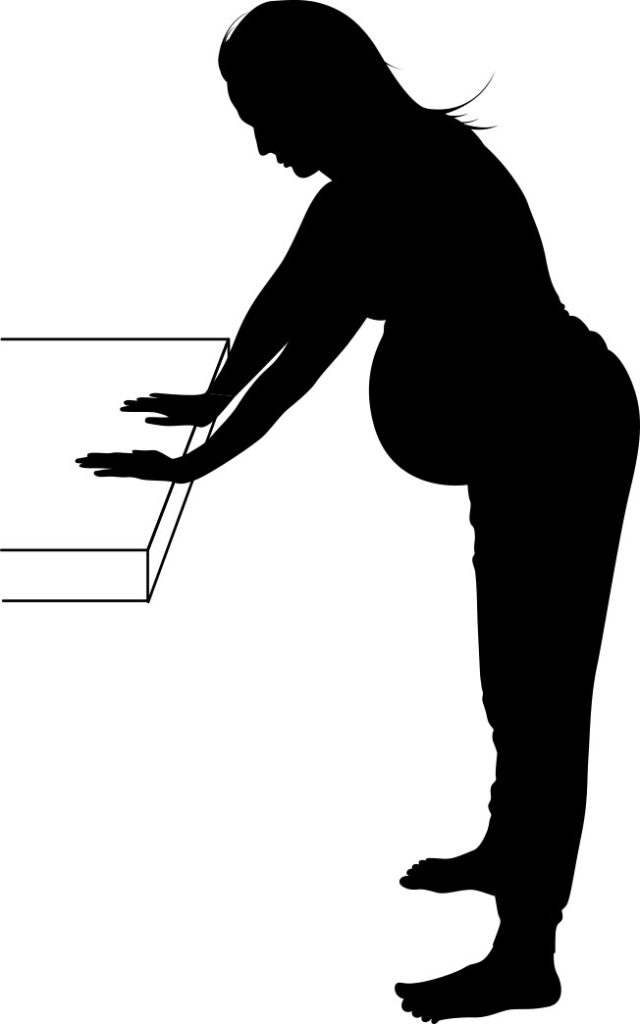

The growing uterus tends to lie toward one side of the pregnant woman’s abdomen, putting pressure on that ureter and causing urine to build up in the kidney. Nurses can instruct the pregnant woman to bend at the hips and support themselves on a table or sink to alleviate some of this pressure. See Figure 9.8[19] for an illustration of positioning to pull the growing uterus away from the maternal back, relieve pressure on the ureter, and allow urine to flow into the bladder. This position also straightens the spine, relieving lower back ache.

Integumentary System Changes During Pregnancy

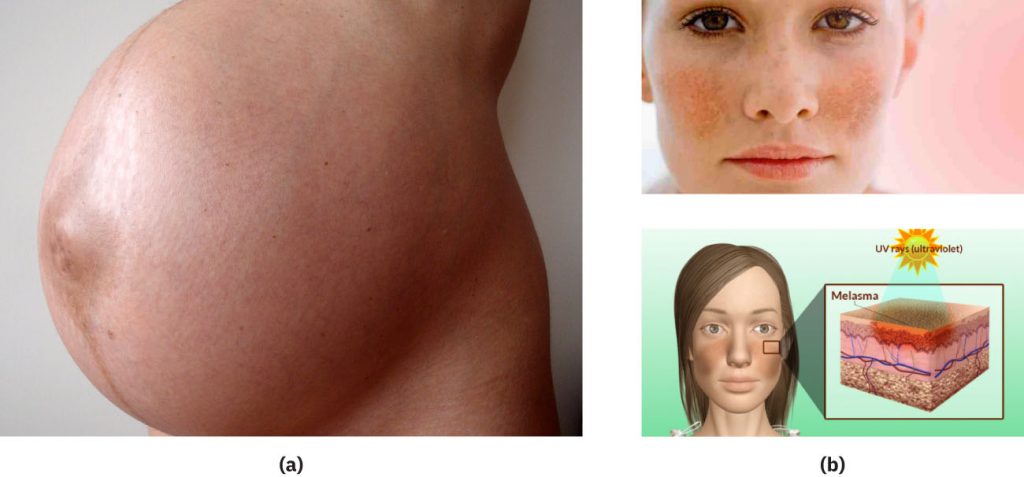

Changes in skin pigmentation occur during pregnancy due to increased estrogen, progesterone, and melanocyte-stimulating hormone levels. The pregnant woman may experience linea nigra, a vertical line of increased pigmentation, which starts at the pubic hair line, passes through the umbilicus, and goes up to the xiphoid process. The pregnant woman may also experience melasma, commonly called the mask of pregnancy, which is hyperpigmentation on the face from the cheekbones to the forehead. Both the linea nigra and melasma get darker in the sun, so nurses should advise pregnant women to wear a hat and to cover the abdomen when spending time in the sun. Hyperpigmentation also occurs on the nipples, perineum, and axilla.[20] See Figure 9.9[21] for an image of linea nigra and melasma.

Striae gravidarum, commonly called stretch marks, are reddish lines where the skin has stretched to accommodate the growth in the breasts, abdomen, and buttocks during pregnancy. Estrogen, relaxin, and adrenocorticosteroids affect the strength of the collagen within the skin, contributing to the formation of the striae. Applying lotions and creams to the skin during pregnancy has not been shown to decrease the occurrence of striae gravidarum, but these products can help to decrease itching. See Figure 9.10[22] for an image of striae gravidarum.

Some pregnant women may develop a benign rash that consists of pruritic urticarial papules and plaques of pregnancy (PUPPP). The rash starts on or near striae on the abdomen and can spread to the arms, legs, back, and buttocks. The cause of PUPPP is unknown. Corticosteroid lotions can help relieve the itching. The rash disappears shortly after giving birth. See Figure 9.11[23] for an image of PUPPP.

Musculoskeletal System Changes During Pregnancy

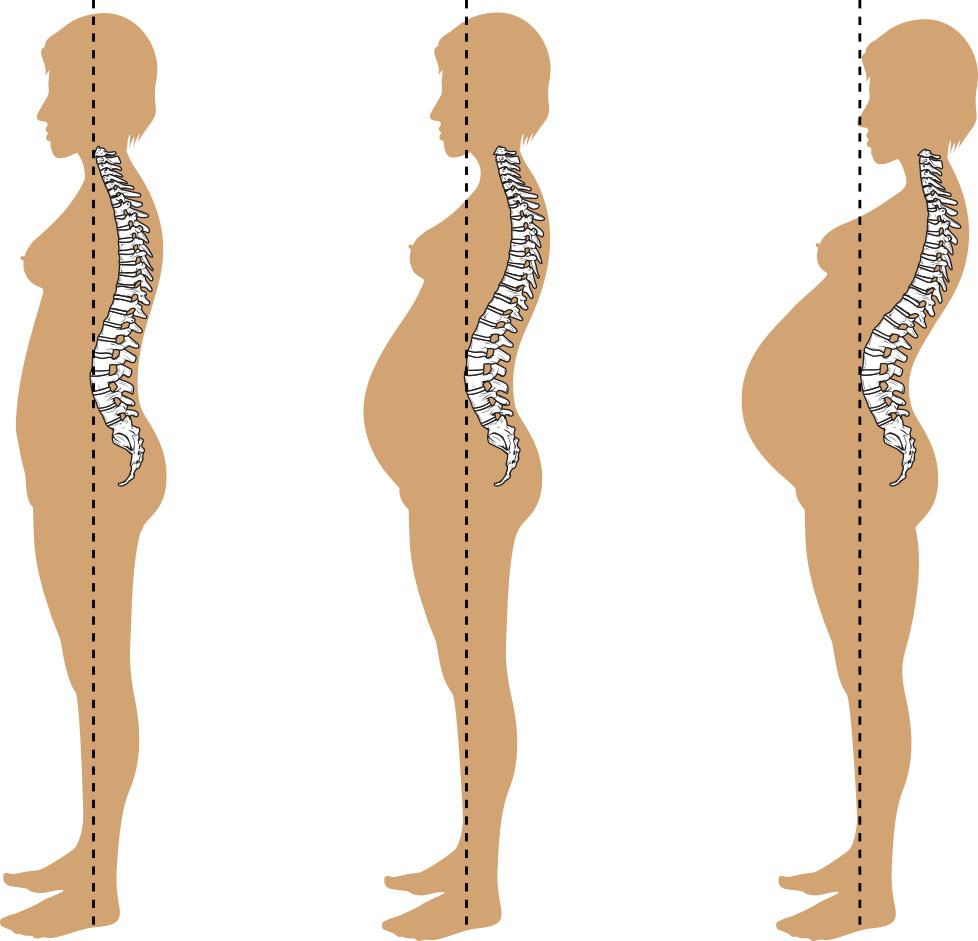

The hormones relaxin and progesterone cause relaxation and stretching of the pelvic joints to facilitate vaginal birth by increasing the inside diameters of the pelvis. This stretching may cause the appearance of waddling while walking and can also cause round ligament pain. The pregnant woman’s center of gravity also shifts as the uterus enlarges, causing lordosis (inward curvature of the lumbar spine) and posture changes that can cause lower back pain. See Figure 9.12[24] for an illustration of lordosis during pregnancy. In some instances, pressure from the enlarging uterus can cause a separation of the rectus abdominis muscle, called diastasis recti. Severe separation of this muscle can affect muscular support in future pregnancies. Muscle cramping may also occur due to hypocalcemia or dehydration.

Nervous System Changes During Pregnancy

Due to the release of multiple hormones and physical changes that occur during pregnancy, the pregnant woman may experience problems with their sleep patterns. They may experience difficulty falling asleep or have frequent awakenings due to active fetal movements and nocturia (frequent urination at night). They may also experience decreased attention, concentration, and memory. Increased blood volume and vascular system changes can exacerbate carpal tunnel syndrome and sciatica.[25]

Immune System Changes During Pregnancy

The maternal immune system is modulated by progesterone to prevent rejection of the fetus as a foreign body. However, it is also characterized by reinforcements to recognize and respond to pathogens to prevent infection and maintain the well-being of the mother and the fetus.[26]

Endocrine System Changes During Pregnancy

Several changes occur to the endocrine system during pregnancy and can have an impact on the growth and development of the fetus. An increase in T4 production occurs due to an increase in vascularity and hyperplasia of the thyroid gland. The pituitary gland enlarges and supports the pregnancy through the secretion of several hormones, including prolactin and oxytocin. During pregnancy there is an increased need for insulin due to the hormones affecting insulin resistance. As the pregnancy advances and the placenta enlarges, the need for insulin increases, and a deficiency can become more apparent.[27]

The basal metabolic rate of pregnant women increases by 10-20% due to the increased oxygen consumption. The pregnant woman must meet their own tissue requirements, prepare for labor and lactation, and contribute to fetal growth and development. The client may also experience increased fluid retention due to increased blood volume, as well as fluid needed for fetal, placenta, and amitotic fluid development.[28]

Placenta Hormones

The placenta hormones that play a major role during pregnancy are human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG), progesterone, estrogen, human placental lactogen (hPL), and relaxin. The hormones produced by the placenta are responsible for the establishment, progression, and maintenance of a pregnancy and promote fetal growth and development. The role of the placenta hormones in the physiologic adaptations of the pregnant woman, as well as fetal growth and development, is summarized in Table 9.4d.

Table 9.4d. Functions of the Placenta Hormones[29]

| Hormone | Functions During Pregnancy |

|---|---|

| Human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG) |

|

| Human placental lactogen (hPL) |

|

| Estrogen |

|

| Progesterone |

|

| Relaxin |

|

Psychological Changes During Pregnancy

Several psychological changes may occur during the three trimesters of pregnancy.

During the first trimester (gestational Week 1-Week 13 and 6 days), the primary focus of the pregnant woman tends to be the self, especially if they are experiencing discomforts like nausea, vomiting, and fatigue. The mother and her partner may experience uncertainty and ambivalence about the pregnancy. They may experience concerns regarding teratogen exposure and the health of the fetus. The partner may experience stress and concern for the mother. Nurses assess maternal attachment to the fetus and identify families at risk for maladaptive behaviors due to risk factors like unintended pregnancy, pattern of family violence, mental health issues, and social determinants of health.[30]

During the second trimester (gestational Week 14-Week 27 weeks and 6 days), the pregnant woman tends to experience a sense of well-being with return of energy and resolution of nausea and vomiting. The fetus typically becomes the focus of the mother.[31]

During the third trimester (gestational Week 28-Week 40 weeks and 6 days), anticipation of labor and childbirth may cause heightened anxiety as the due date approaches, with concerns about pain during childbirth and knowing when to go to the health care facility. The pregnant woman may also feel anxious about the physical discomforts of late pregnancy and the impending responsibilities of parenthood. They may worry about potential fetal harms and become more protective of the pregnancy. They may demonstrate increasing dependence on their partner during the last weeks of pregnancy with increased needs for love and attention. If these needs are met, the pregnant woman may feel more secure and able to cope. The third trimester often brings increased physical discomfort due to the growing size of the uterus and pressure on the mother’s organs. This discomfort can contribute to mood changes and irritability. Many women experience a strong urge to prepare for the arrival of the baby during the third trimester. This can involve nesting behaviors such as organizing the nursery, washing baby clothes, and completing other preparations for the baby’s arrival.[32]

Cultural Influences on Childbearing

The culture of the pregnant woman influences their acceptance of and adaptation to the pregnancy. Cultural beliefs and practices related to pregnancy encompass role expectations of pregnant women and their support person(s); dietary preferences and restrictions; health promotion practices; religious preferences; and pregnancy, labor, and birth practices. When gathering cultural data, the nurse should respect the pregnant woman’s beliefs, values, and behaviors. Other actions by the nurse demonstrating cultural awareness include listening to the pregnant woman, providing nonjudgmental care within an environment of trust, discovering religious and spiritual influences on pregnancy and birth expectations, and understanding the pregnant woman’s family dynamics.[33]

After establishing a culturally sensitive environment, nurses should incorporate a cultural assessment when caring for all pregnant clients. There are many assessment guides used for client interviews that are adaptable to a variety of health care settings and are designed to facilitate understanding and communication. The Four Cs of Culture model[34] is an example of a quick cultural assessment tool that asks questions about what the client Considers to be a problem, the Cause of the problem, how they are Coping with the problem, and how Concerned they are about the problem. See the following box for examples of sample answers to the four Cs assessment.

Four Cs of Culture[35]

- What does the client Consider to be the problem and what they Call it? (In other words, “What do you think is wrong? What is worrying you?”)

- For example, a pregnant client in her first trimester experiencing daily nausea and vomiting believes her body is “unbalanced.”

- What does the client think Caused this problem?

- For example, the client believes this illness is a punishment for a misdeed. The client avoids eating certain foods to treat the illness while also using home remedies such as herbal tea.

- How Concerned is the client about this problem? (In other words, how serious is this problem?)

- For example, a client views the illness as being “God’s will” and states, “It’s in God’s hands.”

Review information about providing “Culturally Responsive Care” in the “Diverse Patients” chapter of Open RN Nursing Fundamentals, 2e.

- Giles, A., Prusinski, R., & Wallace, L. (2024). Maternal newborn nursing. OpenStax. https://openstax.org/books/maternal-newborn-nursing/pages/1-introduction ↵

- Giles, A., Prusinski, R., & Wallace, L. (2024). Maternal newborn nursing. OpenStax. https://openstax.org/books/maternal-newborn-nursing/pages/1-introduction ↵

- “20f4b79b824880d0f5d0faf77bcf0ac8d62aa913” is derived from work by OpenStax and is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/maternal-newborn-nursing/pages/3-3-health-promotion ↵

- Giles, A., Prusinski, R., & Wallace, L. (2024). Maternal newborn nursing. OpenStax. https://openstax.org/books/maternal-newborn-nursing/pages/1-introduction ↵

- “396050289_a3e853f629_o” by Andrew Bardwell is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 2.0 ↵

- “f62410c80227d53b751569ceded7026e95245583” by OpenStax is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/maternal-newborn-nursing/pages/11-1-first-prenatal-visit#fig-00002 ↵

- Giles, A., Prusinski, R., & Wallace, L. (2024). Maternal newborn nursing. OpenStax. https://openstax.org/books/maternal-newborn-nursing/pages/1-introduction ↵

- Giles, A., Prusinski, R., & Wallace, L. (2024). Maternal newborn nursing. OpenStax. https://openstax.org/books/maternal-newborn-nursing/pages/1-introduction ↵

- Giles, A., Prusinski, R., & Wallace, L. (2024). Maternal newborn nursing. OpenStax. https://openstax.org/books/maternal-newborn-nursing/pages/1-introduction ↵

- Giles, A., Prusinski, R., & Wallace, L. (2024). Maternal newborn nursing. OpenStax. https://openstax.org/books/maternal-newborn-nursing/pages/1-introduction ↵

- “0def9caca480473c4dda9efc1478d94d1fab6075” by OpenStax is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/maternal-newborn-nursing/pages/11-1-first-prenatal-visit#fig-00002 ↵

- Warland, J. (2017). Back to basics: Avoiding the supine position in pregnancy. The Journal of Physiology, 595(4), 1017–1018. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5309362/ ↵

- Giles, A., Prusinski, R., & Wallace, L. (2024). Maternal newborn nursing. OpenStax. https://openstax.org/books/maternal-newborn-nursing/pages/1-introduction ↵

- “8a1d89ec7b041f7fb029c8498192bb6f7e37f600” by OpenStax is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/maternal-newborn-nursing/pages/11-1-first-prenatal-visit#fig-00002 ↵

- Giles, A., Prusinski, R., & Wallace, L. (2024). Maternal newborn nursing. OpenStax. https://openstax.org/books/maternal-newborn-nursing/pages/1-introduction ↵

- American Pregnancy Association. Cholestasis of pregnancy: Causes, symptoms, and treatment. https://americanpregnancy.org/healthy-pregnancy/pregnancy-complications/cholestasis-of-pregnancy/ ↵

- Giles, A., Prusinski, R., & Wallace, L. (2024). Maternal newborn nursing. OpenStax. https://openstax.org/books/maternal-newborn-nursing/pages/1-introduction ↵

- Giles, A., Prusinski, R., & Wallace, L. (2024). Maternal newborn nursing. OpenStax. https://openstax.org/books/maternal-newborn-nursing/pages/1-introduction ↵

- “9109ade1f701eacf438518e8c72e59092d2f30d5” by OpenStax is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/maternal-newborn-nursing/pages/11-1-first-prenatal-visit#fig-00002 ↵

- Giles, A., Prusinski, R., & Wallace, L. (2024). Maternal newborn nursing. OpenStax. https://openstax.org/books/maternal-newborn-nursing/pages/1-introduction ↵

- “7c988483460baa3361b5a595417423e6c2ba4e39” by OpenStax is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/maternal-newborn-nursing/pages/11-1-first-prenatal-visit#fig-00002 ↵

- “6d2e0e9923760c95f2d014ca802602941061006d” by OpenStax is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/maternal-newborn-nursing/pages/11-1-first-prenatal-visit#fig-00002 ↵

- “7694e6a12ef39057727b43c745b5f176472ccaaa” by OpenStax is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/maternal-newborn-nursing/pages/11-1-first-prenatal-visit#fig-00002 ↵

- “4855f42ed6953acbb2532157cb5c00a97c9f6a6c” by OpenStax is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/maternal-newborn-nursing/pages/11-1-first-prenatal-visit#fig-00002 ↵

- Giles, A., Prusinski, R., & Wallace, L. (2024). Maternal newborn nursing. OpenStax. https://openstax.org/books/maternal-newborn-nursing/pages/1-introduction ↵

- Mor, G., & Cardenas, I. (2010). The immune system in pregnancy: A unique complexity. American Journal of Reproductive Immunology, 63(6), 425–433. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3025805/ ↵

- Giles, A., Prusinski, R., & Wallace, L. (2024). Maternal newborn nursing. OpenStax. https://openstax.org/books/maternal-newborn-nursing/pages/1-introduction ↵

- Giles, A., Prusinski, R., & Wallace, L. (2024). Maternal newborn nursing. OpenStax. https://openstax.org/books/maternal-newborn-nursing/pages/1-introduction ↵

- Giles, A., Prusinski, R., & Wallace, L. (2024). Maternal newborn nursing. OpenStax. https://openstax.org/books/maternal-newborn-nursing/pages/1-introduction ↵

- Giles, A., Prusinski, R., & Wallace, L. (2024). Maternal newborn nursing. OpenStax. https://openstax.org/books/maternal-newborn-nursing/pages/1-introduction ↵

- Giles, A., Prusinski, R., & Wallace, L. (2024). Maternal newborn nursing. OpenStax. https://openstax.org/books/maternal-newborn-nursing/pages/1-introduction ↵

- Giles, A., Prusinski, R., & Wallace, L. (2024). Maternal newborn nursing. OpenStax. https://openstax.org/books/maternal-newborn-nursing/pages/1-introduction ↵

- Culturally and Linguistically Appropriate Services. (n.d.). Maternal health care. https://thinkculturalhealth.hhs.gov/maternal-health-care/courses/1/intro/1 ↵

- Galanti, G. A. (2014). Caring for patients from different cultures (5th ed.). University of Pennsylvania Press. ↵

- Galanti, G. A. (2014). Caring for patients from different cultures (5th ed.). University of Pennsylvania Press. ↵

These contractions are mild, irregular (i.e., without a pattern), do not get more intense or more frequent, and do not cause cervical changes. They often go away when the woman walks, rests, or changes position.

A small opening in the middle of the cervix that can be visualized and palpated during physical examination.

A temporary structure in the ovary that forms after ovulation and produces progesterone to support early pregnancy.

An antibody-rich secretion that helps develop the newborn’s immunity.

A mild type of anemia that occurs during pregnancy when plasma volume increases faster than red blood cell mass.

An increase in the ability of the blood to coagulate.

A liver condition that can occur in late pregnancy that triggers intense itching, but without a rash.

A vertical line of increased pigmentation, which starts at the pubic hair line, passes through the umbilicus, and goes up to the xiphoid process.

Commonly called the mask of pregnancy, which is hyperpigmentation on the face from the cheekbones to the forehead.

Commonly called stretch marks, are reddish lines where the skin has stretched to accommodate the growth in the breasts, abdomen, and buttocks during pregnancy.

Inward curvature of the lumbar spine.

Caused by a weakening between the two rectus abdominis muscles.