3.2 Basic Concepts Related to Nutrition

Essential Nutrients

Before we begin our discussion on teaching clients about healthy diets, let’s review the different food groups and nutrient-rich sources of vitamins and minerals.

Nutrients from food and fluids are used by the body for growth, energy, and bodily processes. Essential nutrients refer to nutrients that are necessary for bodily functions but must come from dietary intake because the body is unable to synthesize them. Essential nutrients include vitamins, minerals, some amino acids, and some fatty acids.[1] Essential nutrients can be further divided into macronutrients and micronutrients.

Macronutrients

Macronutrients make up most of a person’s diet and provide energy, as well as essential nutrient intake. Macronutrients include carbohydrates, proteins, and fats. However, too many macronutrients without associated physical activity cause overnutrition that can lead to obesity, cardiovascular disease, diabetes mellitus, kidney disease, and other chronic diseases. Too few macronutrients result in undernutrition, which contributes to nutrient deficiencies and malnourishment.[2]

Carbohydrates

Carbohydrates are sugars and starches and are an important energy source that provides 4 kcal/g of energy. Simple carbohydrates are small molecules (called monosaccharides or disaccharides) and break down quickly. As a result, simple carbohydrates are easily digested and absorbed into the bloodstream, so they raise blood glucose levels quickly. Examples of simple carbohydrates include table sugar, syrup, soda, and fruit juice. Complex carbohydrates are larger molecules (called polysaccharides) that break down more slowly, which causes slower release into the bloodstream and a slower increase in blood sugar over a longer period of time. Examples of complex carbohydrates include whole grains, whole fruits, beans, and vegetables.[3] Nurses teach clients to eat complex carbohydrates instead of simple carbohydrates, such as eating a whole apple instead of drinking a cup of apple juice.

Foods can also be categorized according to their glycemic index, a measure of how quickly glucose levels increase in the bloodstream after carbohydrates are consumed. The glycemic index was initially introduced as a way for people with diabetes mellitus to control their blood glucose levels. For example, processed foods, white bread, white rice, and white potatoes have a high glycemic index. They quickly raise blood glucose levels after being consumed and also cause the release of insulin, which can result in more hunger and overeating. However, foods such as most fruit, green leafy vegetables, raw carrots, kidney beans, chickpeas, lentils, and bran breakfast cereals have a low glycemic index. These foods minimize blood sugar spikes and insulin release after eating, which leads to less hunger and overeating. Eating a diet of low glycemic foods has been linked to a decreased risk of obesity and diabetes mellitus.[4]

See Figure 3.1[5] for an image of the glycemic index of a variety of foods.

Proteins

Proteins are peptides and amino acids that provide 4 kcal/g of energy. Proteins are necessary for tissue repair and function, growth, energy, fluid balance, clotting, and the production of white blood cells. Protein status is also referred to as nitrogen balance. Nitrogen is consumed in dietary intake and excreted in the urine and feces. If the body excretes more nitrogen than it takes in through the diet, this is referred to as a negative nitrogen balance. Negative nitrogen balance is seen in clients with starvation or severe infection. Conversely, if the body takes in more nitrogen through the diet than what is excreted, this is referred to as a positive nitrogen balance.[6] During positive nitrogen balance, excess protein is converted to fat tissue for storage.

Proteins are classified as complete, incomplete, or partially complete. Complete proteins must be ingested in the diet. They have enough amino acids to perform necessary bodily functions, such as growth and tissue maintenance. Examples of foods containing complete proteins are soy, quinoa, eggs, fish, meat, and dairy products. Incomplete proteins do not contain enough amino acids to sustain life. Examples of incomplete proteins include most plants, such as beans, peanut butter, seeds, grains, and grain products. Incomplete proteins must be combined with other types of proteins to add to amino acids and form complete protein combinations.[7] For example, vegetarians must be careful to eat complementary proteins, such as grains and legumes, or nuts and seeds and legumes, to create complete protein combinations during their daily food intake. Partially complete proteins have enough amino acids to sustain life, but not enough for tissue growth and maintenance. Because of the similarities, most sources consider partially complete proteins to be in the same category as incomplete proteins. See Figure 3.2[8] for an image of protein-rich foods.

Fats

Fats consist of fatty acids and glycerol and are essential for tissue growth, insulation, energy, energy storage, and hormone production. Fats provide 9 kcal/g of energy.[9] While some fat intake is necessary for energy and uptake of fat-soluble vitamins, excess fat intake contributes to heart disease and obesity.

Fats are classified as saturated, unsaturated, and trans fatty acids. Saturated fats are those that come from animal products, such as butter and red meat (e.g., steak). Saturated fats are solid at room temperature. Recommended intake of saturated fats is less than 10% of daily calories because saturated fat raises cholesterol and contributes to heart disease.[10]

Unsaturated fats come from oils and plants, although chicken and fish also contain some unsaturated fats. Unsaturated fats are healthier than saturated fats. Examples of unsaturated fats include olive oil, canola oil, avocados, almonds, and pumpkin seeds. Fats containing omega-3 fatty acids are considered polyunsaturated fats and help lower LDL cholesterol levels. Fish and other seafood are excellent sources of omega-3 fatty acids.

Trans fats are fats that have been altered through a hydrogenation process, so they are not in their natural state. During the hydrogenated process, fat is changed to make it harder at room temperature and have a longer shelf life. Trans fats are found in processed foods, such as chips, crackers, and cookies, as well as in some margarines and salad dressings. Minimal, if any, trans fat intake is recommended because it increases cholesterol and contributes to heart disease.[11]

Micronutrients

Micronutrients include vitamins and minerals.

Vitamins

Vitamins are necessary for many bodily functions, including growth, development, healing, vision, and reproduction. Most vitamins are considered essential because they are not manufactured by the body and must be ingested in the diet. Vitamin D is also manufactured through exposure to sunlight.[12]

Vitamin toxicity can be caused by overconsumption of certain vitamins, such as vitamins A, D, C, B6, and niacin. Conversely, vitamin deficiencies can be caused by various factors, including poor food intake due to social determinants of health, malabsorption problems with the gastrointestinal tract, drug and alcohol misuse, proton pump inhibitors, and prolonged parenteral nutrition. Deficiencies can take years to develop, so it is usually a long-term problem for clients.[13]

Vitamins are classified as water soluble or fat soluble. Water-soluble vitamins are not stored in the body and include vitamin C and B-complex vitamins: B1 (thiamine), B2 (riboflavin), B3 (niacin), B6 (pyridoxine), B12 (cyanocobalamin), and B9 (folic acid). Additional water-soluble vitamins include biotin and pantothenic acid. Excess amounts of these vitamins are excreted through the kidneys in urine, so toxicity is rarely an issue, though excess intake of vitamin B6, C, or niacin can result in toxicity.[14] See Table 3.2a for a list of selected water-soluble vitamins, their sources, and their function.[15],[16],[17],[18],[19],[20],[21],[22],[23]

Table 3.2a. Selected Water-Soluble Vitamins

| Water-Soluble Vitamin | Sources | Functions | Deficiency |

|---|---|---|---|

| C (Ascorbic Acid) | Citrus fruits, broccoli, greens, sweet peppers, tomatoes, lettuce, potatoes, tropical fruits, and strawberries | Infection prevention, wound healing, collagen formation, iron absorption, amino acid metabolism, antioxidant, and bone growth in children. | Early Signs: weakness, weight loss, myalgias, and irritability. Late Signs: scurvy, swollen gums, loose teeth, bleeding gums and skin, poor wound healing, edema, leg pain, anorexia, irritability, and poor growth in children. |

| B1 (Thiamine) | Nuts, liver, whole grains, pork, and legumes | Nerve function; metabolism of carbohydrates, fat, amino acids, glucose, and alcohol; appetite and digestion. | Fatigue, memory deficits, insomnia, chest pain, abdominal pain, anorexia, numbness of extremities, muscle wasting, heart failure, and shock in severe cases. |

| B2 (Riboflavin) | Eggs, liver, leafy greens, milk, and whole grains | Protein and carbohydrate metabolism, healthy skin, and vision. | Pallor, lip fissures, and seborrheic dermatitis. |

| B3 (Niacin) | Fish, chicken, eggs, dairy, mushrooms, peanut butter, whole grains, and red meat | Glycogen metabolism, cell metabolism, tissue regeneration, fat synthesis, nerve function, digestion, and skin health. | Pellagra characterized by skin lesions at pressure points/sun exposed skin, glossitis (swollen tongue), constipation progressing to bloody diarrhea, abdominal pain, abdominal distention, nausea, psychosis, and encephalopathy. |

| B6 (Pyridoxine) | Organ meats, fish, and various fruits and vegetables | Protein metabolism and red blood cell formation. | Rare due to presence in most foods. Peripheral neuropathy, seizures, anemia, glossitis (swollen tongue), seborrheic dermatitis, depression, and confusion. |

| B9 (Folic Acid) | Liver, legumes, leafy greens, seeds, orange juice, and enriched refined grains | Coenzyme in protein metabolism and cell growth, red blood cell formation, and prevention of fetal neural tube defects in utero. | Glossitis (swollen tongue), confusion, depression, diarrhea, anemia, and fetal neural tube defects. |

| B12 (Cyanocobalamin) | Meat, organ meat, dairy, seafood, poultry, and eggs | Mature red blood cell formation, DNA/RNA synthesis, new cell formation, and nerve function. | Pernicious anemia from lack of intrinsic factor in intestines. Early Signs: weight loss, abdominal pain, peripheral neuropathy, weakness, hyporeflexia, and ataxia. Late Signs: irritability, depression, paranoia, and confusion. |

Fat-soluble vitamins are absorbed with fats in the diet and include vitamins A, D, E, and K. They are stored in fat tissue and can build up in the liver. They are not excreted easily by the kidneys due to storage in fatty tissue and the liver, so overconsumption can cause toxicity, especially with vitamins A and D.[24] See Table 3.2b for a list of selected fat-soluble vitamins, their sources, their function, and manifestations of deficiencies and toxicities.[25],[26],[27],[28],[29],[30],[31],[32]

Table 3.2b. Selected Fat-Soluble Vitamins

| Fat-Soluble Vitamin | Source | Function | Deficiency | Toxicity |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| A (Retinol)

|

Retinol: fortified milk and dairy, egg yolks, and fish liver oil

Beta carotene: green leafy vegetables, and dark orange fruits and vegetables |

Eyesight, epithelial, bone and tooth development, normal cellular proliferation, and immunity. | Night blindness, rough scaly skin, dry eyes, and poor tooth/bone development. Causes poor growth and infections common with mortality >50%. | Dry, itchy skin; headache; nausea; blurred vision; and yellowing skin (carotenosis). |

| D | Milk, dairy, egg yolks, fatty fish, liver, and sun exposure | Changed to active form with sun exposure. Needed for calcium/ phosphorus absorption, immunity, and bone strength. | Rickets, poor dentition, tetany, osteomalacia, muscle aches and weakness, bone pain, poor calcium absorption leading to hypocalcemia and subsequent hyperparathyroidism and tetany. | Hypercalcemia resulting in nausea, vomiting, anorexia, renal failure, weakness, pruritus, and polyuria. |

| E | Green leafy vegetables, whole grains, liver, egg yolks, nuts, and plant oils | Anticoagulant, antioxidant, and cellular protection. | Red blood cell breakdown leading to anemia, neuron degeneration, neuropathy, and retinopathy. | Rare. Occasionally muscle weakness, fatigue, GI upset with diarrhea, and hemorrhagic stroke. |

| K | Green leafy vegetables and green vegetables

|

Needed for producing clotting factors in the liver. | Rare in adults. Prolonged clotting times, hemorrhaging (especially in newborns causing morbidity and mortality), and jaundice. | Can interfere with effectiveness of certain anticoagulant medications, such as warfarin. |

Minerals

Minerals are inorganic materials essential for hormone and enzyme production, as well as for bone, muscle, neurological, and cardiac function. Minerals are needed in varying amounts and are obtained from a well-rounded diet. In some cases of deficiencies, mineral supplements may be prescribed by a health care provider. Deficiencies can be caused by malnutrition, malabsorption, or certain medications, such as diuretics.

Minerals are classified as either macrominerals or trace minerals. Macrominerals are needed in larger amounts and are typically measured in milligrams, grams, or milliequivalents. Macrominerals include sodium, potassium, calcium, magnesium, chloride, and phosphorus.

Review additional information about macrominerals in the “Electrolytes” section of the “Fluids and Electrolytes” chapter in Open RN Nursing Fundamentals, 2e.

Trace minerals are needed in tiny amounts. Trace minerals include zinc, iron, chromium, copper, fluorine, iodine, manganese, molybdenum, and selenium.[33] See Table 3.2c for a list of selected macrominerals and Table 3.2d for a list of trace minerals.[34],[35],[36],[37]

Table 3.2c. Macrominerals

| Macromineral | Source | Function |

|---|---|---|

| Sodium | Table salt, spinach, and milk | Fluid and electrolyte balance |

| Potassium | Legumes, potatoes, bananas, and whole grains | Muscle contraction, cardiac muscle function, and nerve function |

| Calcium | Dairy, eggs, and green leafy vegetables | Bone and teeth development, nerve function, muscle contraction, immunity, and blood clotting |

| Magnesium | Raw nuts, spinach (cooked has higher magnesium content), tomatoes, and beans | Cell energy, muscle function, cardiac function, and glucose metabolism |

| Chloride | Table salt | Fluid and electrolyte balance and digestion |

| Phosphorus | Red meat, poultry, rice, oats, dairy, and fish | Bone strength and cellular function |

Table 3.2d. Trace Minerals

| Trace Mineral | Source | Function |

|---|---|---|

| Zinc | Eggs, spinach, yogurt, whole grains, fish, and brewer’s yeast | Immune function, wound healing, and vision |

| Iron | Red meat, organ meats, spinach, shrimp, tuna, salmon, kidney beans, peas, and lentils | Hemoglobin and collagen production |

| Chromium | Whole grains, meat, and brewer’s yeast | Glucose metabolism |

| Copper | Shellfish, fruits, nuts, and organ meats | Hemoglobin, collagen, elastin, neurotransmitter, and melanin production |

| Fluorine | Fluoridated water and toothpaste | Retention of calcium in bones and teeth |

| Iodine | Iodized salt and seafood | Energy production and thyroid function |

| Manganese | Whole grain and nuts | Not fully understood |

| Molybdenum | Organ meats, green leafy vegetables, legumes, whole grains, and dairy | Not fully understood; detoxification |

| Selenium | Broccoli, cabbage, garlic, whole grains, brewer’s yeast, celery, onions, and organ meats | Not fully understood |

Review concepts related to nutrition in the “Basic Concepts” section of the “Nutrition” chapter in Open RN Nursing Fundamentals, 2e.

Reading Food Labels

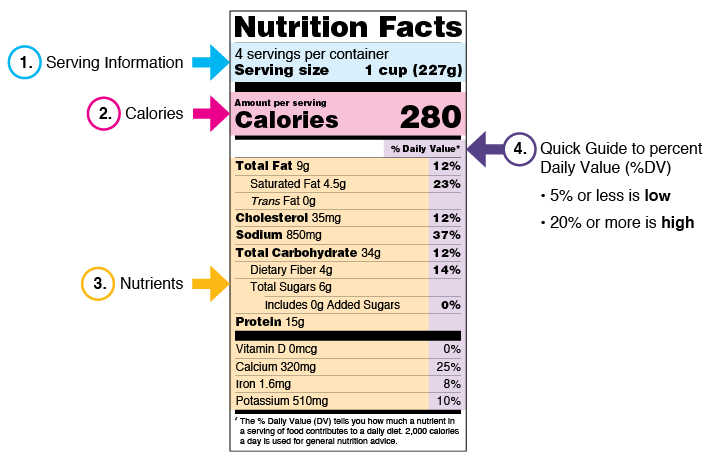

Understanding how to read food labels is an important skill for nurses and clients to learn when developing healthy eating plans. See Figure 3.3[38] for an example of a food label. Each section of the food label is further discussed in the following subsections.

Serving Information

This section of the label provides information on the number of servings in a container, as well as a serving size. When viewing the other sections of the food label, remember the numbers are based on the established serving size.

Calories

Calories are a measure of how much energy is provided when the food or drink is consumed. For example, if a person eats ½ cup (or half a serving of the food listed on the label above), they will consume 140 calories. Conversely, if they eat two cups, they will consume 560 calories.

Nutrients

This section provides information on established daily nutrients that can impact our health, including fat, cholesterol, sodium, total carbohydrate, and protein. Saturated fat, sodium, and added sugars are items that should be limited or avoided.

Under the bolded line is a list of other nutrients included in this food or beverage. For example, this label includes information on vitamin D, calcium, iron, and potassium.

Percent Daily Value

Percent daily values (% DV) show how much one serving size of the food or beverage contributes to the total daily recommended amounts of each nutrient identified. Food labels use 2,000 calories per day as a general guideline for caloric recommendations, but actual caloric recommendations are based on an individual’s age, height, weight, and activity level. For example, the label in Figure 3.3 shows one serving accounts for 37% of the daily total recommendation for sodium. However, the container contains four servings, so if the entire container is consumed, the daily recommended amount of sodium is exceeded.

A specific individual may require more or less intake of a specific nutrient listed on the label. For example, a client with chronic kidney disease may be prescribed a restricted amount of protein and potassium in their diet, whereas a client with hypertension treated with diuretics may require higher levels of potassium.

Factors Affecting Clients’ Diets

Several factors, such as cultural and/or religious beliefs, vegetarian diet choices, and conditions like lactose intolerance, can significantly impact an individual’s dietary intake.

Cultural and Religious Beliefs

Cultural and religious values and beliefs can impact what foods are eaten, how they are prepared, and when meals are consumed. Nurses consider these factors when working collaboratively with individuals to develop a healthy eating plan.[39]

Most cultural and religious beliefs are a combination of values, beliefs, and habits that have been passed down through family members and other authority figures. Cultural beliefs can impact a client’s diet in several ways, such as traditional food choices for meals. Most cultures have traditional staple foods, such as bread, pasta, or rice, and use particular ways of preparing foods.

Cultural and religious beliefs may also impact a client’s food intake due to fasting or other dietary restrictions. For example, during the thirty-day month of Ramadan, Muslims refrain from food and drink from dawn until sundown. Although anyone who is ill is not obligated to fast, hospitalized clients may wish to follow this tradition. In these cases, nurses can investigate options for predawn meals and for delaying dinner until after sunset.[40]

Several religious beliefs include dietary restrictions. For example, Jewish clients may request a special Kosher diet that has specific rules regarding slaughter of certain foods (e.g., beef), prohibition of certain foods (e.g., pork and gelatin), or prohibition of combinations of certain foods (e.g., beef served with dairy products). Clients from some religions, such as Buddhists, are strictly vegetarian and refuse to consume any meat or animal by-product. Clients from some religions may refuse to consume specific types of meat. For example, Muslim clients may not eat pork or gelatin. Clients from other religions may follow non-meat diets only during religious holidays. For example, some Roman Catholics avoid eating meat on Fridays during Lent, the 40 days before the Easter holiday. Additionally, handwashing before eating may have a religious significance for many clients.[41]

Review additional information about common religious practices that may impact nursing care in the “Common Religions and Spiritual Practices” section in the “Spirituality” chapter of Open RN Nursing Fundamentals, 2e.

In addition to religious beliefs, cultural preferences may impact an individual’s food choices, such as the following examples[42]:

- Hispanic: Eating homemade traditional food with the family is important. Common foods are beans, rice, corn, tacos, enchiladas, pork, fish, and steak, along with specialty sauces. While these foods are considered healthy choices, they may be high in fat and sodium.

- Chinese: Preferences vary depending on the originating region of China. Foods are classified as warm or cold, yin or yang, and chosen according to the client’s health condition. Beef, lamb, tofu, and chicken, along with vegetables, rice, bread, buns, or steamed buns, are typical choices. This diet may contain high sodium from soy sauce, protein, and refined carbohydrates.

- Japanese: Diets often contain fish and seafood, which could be grilled or raw. The seafood provides polyunsaturated, omega-3 fatty acid. Other protein sources may come from tofu or meat. Miso, soy sauce, and tofu come from soy. Soy sauce, pickled vegetables, and miso may add high sodium to the diet.

- Indian: Diets often include lacto-vegetarian choices. Protein may be plant-based, chicken, mutton, or goat. This diet may be high in calcium and carbohydrates but low in vitamin B12.

- Middle Eastern: This diet includes a wide variety of plant and animal sources of foods. The diet may be high in fiber, iron, and poly- and mono-unsaturated fat coming from chickpeas, lentils, walnuts, and almonds.

- African American: Eating with family is an important tradition. Traditional diets may include beans and peas, collard or turnip greens, cabbage, sweet potatoes, rice, pork, fish, and chicken. Foods may be prepared by frying in oil.[43]

Vegetarian and Vegan Diets

Individuals may follow a vegetarian and vegan diet for a variety of reasons, such as cultural/religious/spiritual beliefs, health reasons, or broad environmental concerns. Vegetarian diets include beans, grains, and fruits and vegetables but do not contain red meat, poultry, seafood, or other animal flesh. A lacto-vegetarian diet includes dairy products, and a lacto-ovo-vegetarian diet includes dairy products and eggs. A vegan diet is the most restrictive vegetarian diet and does not include dairy, eggs, or other animal products (including seafood).

Well-balanced vegetarian diets can lower the risk of a number of chronic conditions, including heart disease, diabetes, and obesity. However, if a vegetarian diet does not include a variety of food choices, it may be insufficient in calcium, iron, omega-3 fatty acids, zinc, and vitamin B12.[44] Nurses teach clients eating vegetarian diets how to avoid these insufficiencies in food choices by referring them to a dietician.

Lactose Intolerance

In addition to cultural and religious beliefs, other conditions can impact a client’s diet. For example, sixty-five percent of adults have lactose intolerance that affects their dairy intake. Lactose intolerance occurs when the body lacks an enzyme called lactase that breaks down lactose, the type of sugar in milk. Symptoms after ingesting dairy products include gas, bloating, and cramps. Clients from various ethnic groups, such as East Asian, West African American, Arab, Jewish, Mexican American, Native American, Greek, and Italian backgrounds, tend to have lactose intolerance. Nurses help clients understand this condition is a food intolerance and how to select alternative sources of calcium and vitamin D, such as hard and aged cheese, yogurt with active and live cultures, and lactose-free milk. Supplements are also available to help breakdown lactose in dairy products.[45],[46]

Food Insecurity

Food insecurity can impact a client’s diet. Food insecurity refers to limited or uncertain access to nutritious foods because of social determinants of health. In 2020, almost 15% of U.S. households experienced food insecurity at some point in time.[47]

Nurses should screen clients for food insecurity as part of a nutritional assessment. The Hunger Vital Sign screening is easy to use and is increasingly being built into electronic health record systems. The Hunger Vital Sign includes two statements that can be used during a health history interview. The client should respond to each statement as “Often true,” “Sometimes true,” or “Never true” for their household in the last 12 months[48]:

- “We worried whether our food would run out before we got money to buy more.”

- “The food we bought just didn’t last, and we didn’t have money to get more.”

If the client responds “Often true” or “Sometimes true” to either question, the screening for food insecurity is positive and requires additional assessment or referrals to social workers or case managers.

The community in which a client lives can significantly influence food insecurity. For example, food deserts are geographic areas that lack access to affordable, healthy food. These can be rural or urban areas that lack grocery stores with healthy food options.[49]

Food insecurity is associated with poor health outcomes. When people do not have reliable, nutritious food sources, they cannot follow recommended diets and are at increased risk for malnutrition, overnutrition, and long-term health conditions, including diabetes, obesity, and heart disease.[50]

View estimates of food insecurity across America at https://map.feedingamerica.org/.

Food Safety

Food safety is an important concept related to teaching about diet and nutrition. Approximately one in six Americans becomes ill from food poisoning annually.[51] Nurses teach clients to safely handle food to protect themselves from contamination from microorganisms that can cause food-borne illness. Clients can avoid food poisoning by properly washing hands, cleaning utensils and surfaces, separating fresh produce from raw meats and seafood, and cooking and storing food in ways that decrease microbial viability.[52]

Clients should be instructed to wash hands with plain soap and water before preparing and eating food and after handling raw meat, seafood, poultry, or uncooked eggs. Utensils, cutting boards, dishes, and surfaces that have touched raw meat, poultry, seafood, eggs, and flour should be cleaned with hot, soapy water. Cutting boards and utensils used for raw meat, poultry, and seafood should be kept separately from those used for fruits and vegetables to keep from spreading microbes. Utensils and cutting boards used for raw food should also be kept separately from those used for cooked food.[53]

In a similar manner, when purchasing food, raw meats, poultry, and seafood should be kept separate from other food in shopping carts and shopping bags. Raw food should be used or frozen within two or three days of purchase. Eggs should be stored in their original container inside the refrigerator, not the door of the refrigerator.[54]

Fruits and vegetables should be washed to remove pesticides and dirt, but caution should be used if raw meat, poultry, or seafood is washed because water contaminated with microbes can splash on surfaces in the kitchen. Additionally, the safest way to thaw frozen food is in a refrigerator, not on the kitchen counter.[55]

When preparing food, it must be cooked to the correct internal temperature to kill microbes that can cause illness. An internal thermometer should be placed in the thickest part of the food to ensure the proper temperature has been reached for that type of food item. Additionally, hot food should be kept above 140 degrees until it is eaten because lower temperatures allow microbe growth. For example, hamburger should be cooked until it is 160 degrees internally, which kills harmful microbes. It may be safe to eat if it is pink internally, as long as the internal temperature is 160 degrees. Hamburger is prone to cause food poisoning because in the grinding process, microbes on the outside of the meat are mixed into the center. If the meat is not thoroughly cooked, the microbes in the center of the meat may cause illness. When a microwave oven is used, clients should stir the food during cooking to ensure the food is heated throughout because microwaves cook food hotter on the outside.[56]

After a meal is completed, food must be chilled properly to inhibit the growth of microbes. Microbes grow best between 40- and 140-degrees Fahrenheit, so food should only be in this temperature range for up to two hours. Refrigerated food should be chilled in a refrigerator that is 39 degrees or colder or a freezer that is zero degrees or colder.[57]

- Youdim, A. (2023). Overview of nutrition. Merck Manual Professional Version. https://www.merckmanuals.com/professional/nutritional-disorders/nutrition-general-considerations/overview-of-nutrition ↵

- Youdim, A. (2023). Overview of nutrition. Merck Manual Professional Version. https://www.merckmanuals.com/professional/nutritional-disorders/nutrition-general-considerations/overview-of-nutrition ↵

- Youdim, A. (2023). Overview of nutrition. Merck Manual Professional Version. https://www.merckmanuals.com/professional/nutritional-disorders/nutrition-general-considerations/overview-of-nutrition ↵

- Youdim, A. (2023). Overview of nutrition. Merck Manual Professional Version. https://www.merckmanuals.com/professional/nutritional-disorders/nutrition-general-considerations/overview-of-nutrition ↵

- “Eat-Foods-Low-on-the-Glycemic-Index-Step-1-Version-2.jpg” by unknown is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 3.0. Access for free at https://www.wikihow.com/Eat-Foods-Low-on-the-Glycemic-Index#aiinfo ↵

- Youdim, A. (2023). Overview of nutrition. Merck Manual Professional Version. https://www.merckmanuals.com/professional/nutritional-disorders/nutrition-general-considerations/overview-of-nutrition ↵

- Brazier, Y. (2020). How much protein does a person need? Medical News Today. https://www.medicalnewstoday.com/articles/196279 ↵

- “Protein-rich_Foods.jpg” by Smastronardo is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0 ↵

- Youdim, A. (2023). Overview of nutrition. Merck Manual Professional Version. https://www.merckmanuals.com/professional/nutritional-disorders/nutrition-general-considerations/overview-of-nutrition ↵

- Healthwise. (2023). Types of fats. Michigan Medicine at University of Michigan. https://www.uofmhealth.org/health-library/aa160619 ↵

- Healthwise. (2023). Types of fats. Michigan Medicine at University of Michigan. https://www.uofmhealth.org/health-library/aa160619 ↵

- Johnson, L. E. (2022). Overview of vitamins. Merck Manual Professional Version. https://www.merckmanuals.com/professional/nutritional-disorders/vitamin-deficiency,-dependency,-and-toxicity/overview-of-vitamins?redirectid=43#v2089966 ↵

- Johnson, L. E. (2022). Overview of vitamins. Merck Manual Professional Version. https://www.merckmanuals.com/professional/nutritional-disorders/vitamin-deficiency,-dependency,-and-toxicity/overview-of-vitamins?redirectid=43#v2089966 ↵

- Healthwise. (2023). Vitamins: Their functions and sources. Michigan Medicine at University of Michigan. https://www.uofmhealth.org/health-library/ta3868 ↵

- Healthwise. (2023). Vitamins: Their functions and sources. Michigan Medicine at University of Michigan. https://www.uofmhealth.org/health-library/ta3868 ↵

- Healthwise. (2023). Vitamins: Their functions and sources. Michigan Medicine at University of Michigan. https://www.uofmhealth.org/health-library/ta3868 ↵

- Johnson, L. E. (2022). Folate deficiency. Merck Manual Professional Version. https://www.merckmanuals.com/professional/nutritional-disorders/vitamin-deficiency-dependency-and-toxicity/folate-deficiency ↵

- Johnson, L. E. (2022). Niacin deficiency. Merck Manual Professional Version. https://www.merckmanuals.com/professional/nutritional-disorders/vitamin-deficiency-dependency-and-toxicity/niacin-deficiency ↵

- Johnson, L. E. (2022). Riboflavin deficiency. Merck Manual Professional Version. https://www.merckmanuals.com/professional/nutritional-disorders/vitamin-deficiency-dependency-and-toxicity/riboflavin-deficiency ↵

- Johnson, L. E. (2022). Thiamin deficiency. Merck Manual Professional Version. https://www.merckmanuals.com/professional/nutritional-disorders/vitamin-deficiency-dependency-and-toxicity/thiamin-deficiency ↵

- Johnson, L. E. (2022). Vitamin B6 deficiency and dependency. Merck Manual Professional Version. https://www.merckmanuals.com/professional/nutritional-disorders/vitamin-deficiency-dependency-and-toxicity/vitamin-b6-deficiency-and-dependency ↵

- Johnson, L. E. (2022). Vitamin B12 deficiency. Merck Manual Professional Version. https://www.merckmanuals.com/professional/nutritional-disorders/vitamin-deficiency-dependency-and-toxicity/vitamin-b12-deficiency ↵

- Johnson, L. E. (2022). Vitamin C deficiency. Merck Manual Professional Version. https://www.merckmanuals.com/professional/nutritional-disorders/vitamin-deficiency-dependency-and-toxicity/vitamin-c-deficiency ↵

- Healthwise. (2023). Vitamins: Their functions and sources. Michigan Medicine at University of Michigan. https://www.uofmhealth.org/health-library/ta3868 ↵

- Healthwise. (2023). Vitamins: Their functions and sources. Michigan Medicine at University of Michigan. https://www.uofmhealth.org/health-library/ta3868 ↵

- Johnson, L. E. (2022). Vitamin A deficiency. Merck Manual Professional Version. https://www.merckmanuals.com/professional/nutritional-disorders/vitamin-deficiency-dependency-and-toxicity/vitamin-a-deficiency ↵

- Johnson, L. E. (2022). Vitamin D deficiency and dependency. Merck Manual Professional Version. https://www.merckmanuals.com/professional/nutritional-disorders/vitamin-deficiency-dependency-and-toxicity/vitamin-d-deficiency-and-dependency ↵

- Johnson, L. E. (2022). Vitamin D toxicity. Merck Manual Professional Version. https://www.merckmanuals.com/professional/nutritional-disorders/vitamin-deficiency-dependency-and-toxicity/vitamin-d-toxicity ↵

- Johnson, L. E. (2022). Vitamin E deficiency. Merck Manual Professional Version. https://www.merckmanuals.com/professional/nutritional-disorders/vitamin-deficiency-dependency-and-toxicity/vitamin-e-deficiency ↵

- Johnson, L. E. (2022). Vitamin E toxicity. Merck Manual Professional Version. https://www.merckmanuals.com/professional/nutritional-disorders/vitamin-deficiency-dependency-and-toxicity/vitamin-e-toxicity ↵

- Johnson, L. E. (2022). Vitamin K deficiency. Merck Manual Professional Version. https://www.merckmanuals.com/professional/nutritional-disorders/vitamin-deficiency-dependency-and-toxicity/vitamin-k-deficiency ↵

- Johnson, L. E. (2022). Vitamin K toxicity. Merck Manual Professional Version. https://www.merckmanuals.com/professional/nutritional-disorders/vitamin-deficiency-dependency-and-toxicity/vitamin-k-toxicity ↵

- MedlinePlus [Internet]. (2020). Minerals. https://medlineplus.gov/minerals.html ↵

- Texas Heart Institute. (n.d.). Minerals: What they do, where to get them. https://www.texasheart.org/heart-health/heart-information-center/topics/minerals-what-they-do-where-to-get-them/ ↵

- Texas Heart Institute. (n.d.). Trace elements: What they do and where they get them. https://www.texasheart.org/heart-health/heart-information-center/topics/trace-elements/ ↵

- Texas Heart Institute. (n.d.). Minerals: What they do, where to get them. https://www.texasheart.org/heart-health/heart-information-center/topics/minerals-what-they-do-where-to-get-them/ ↵

- Texas Heart Institute. (n.d.). Trace elements: What they do and where they get them. https://www.texasheart.org/heart-health/heart-information-center/topics/trace-elements/ ↵

- “nfl-howtounderstand-labeled.png” by unknown author at FDA.gov is in the Public Domain. Access for free at https://www.fda.gov/food/nutrition-facts-label/how-understand-and-use-nutrition-facts-label ↵

- Brown, T. L. (2003). Meal-planning strategies: Ethnic populations. Diabetes Spectrum, 16(3), 190-192. https://doi.org/10.2337/diaspect.16.3.190 ↵

- Ernstmeyer, K., & Christman, E. (Eds.). (2024). Nursing fundamentals 2E. WisTech Open. https://wtcs.pressbooks.pub/nursingfundamentals/ ↵

- Ernstmeyer, K., & Christman, E. (Eds.). (2024). Nursing fundamentals 2E. WisTech Open. https://wtcs.pressbooks.pub/nursingfundamentals/ ↵

- Nemec, K. (2020). Cultural awareness of eating patterns in the health care setting. Clinical Liver Disease, 16(5), 204-207. https://doi.org/10.1002%2Fcld.1019 ↵

- Moore, M. (2024). Healthy soul food your way. Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics. https://www.eatright.org/food/cultural-cuisines-and-traditions/african-american/healthy-soul-food-your-way ↵

- University of Hawai‘i at Mānoa Food Science and Human Nutrition Program. (n.d.). Human nutrition. https://pressbooks.oer.hawaii.edu/humannutrition ↵

- MedlinePlus [Internet]. (2023). Lactose intolerance. https://medlineplus.gov/genetics/condition/lactose-intolerance/ ↵

- Johns Hopkins Medicine. (n.d.). Lactose intolerance. https://www.hopkinsmedicine.org/health/conditions-and-diseases/lactose-intolerance ↵

- Bilbrew, E. C., Vogelzang, J., & Whittington, K. (n.d.). Nutrition for nurses. OpenStax. https://openstax.org/details/books/nutrition ↵

- Bilbrew, E. C., Vogelzang, J., & Whittington, K. (n.d.). Nutrition for nurses. OpenStax. https://openstax.org/details/books/nutrition ↵

- Bilbrew, E. C., Vogelzang, J., & Whittington, K. (n.d.). Nutrition for nurses. OpenStax. https://openstax.org/details/books/nutrition ↵

- Bilbrew, E. C., Vogelzang, J., & Whittington, K. (n.d.). Nutrition for nurses. OpenStax. https://openstax.org/details/books/nutrition ↵

- FoodSafety.gov. (2021). Keep food safe. https://www.foodsafety.gov/keep-food-safe ↵

- FoodSafety.gov. (2021). Keep food safe. https://www.foodsafety.gov/keep-food-safe ↵

- FoodSafety.gov. (2021). Keep food safe. https://www.foodsafety.gov/keep-food-safe ↵

- FoodSafety.gov. (2021). Keep food safe. https://www.foodsafety.gov/keep-food-safe ↵

- FoodSafety.gov. (2021). Keep food safe. https://www.foodsafety.gov/keep-food-safe ↵

- FoodSafety.gov. (2021). Keep food safe. https://www.foodsafety.gov/keep-food-safe ↵

- FoodSafety.gov. (2021). Keep food safe. https://www.foodsafety.gov/keep-food-safe ↵

Nutrients that are necessary for bodily functions but must come from dietary intake because the body is unable to synthesize them.

Make up most of a person’s diet and provide energy, as well as essential nutrient intake including carbohydrates, proteins, and fats.

Sugars and starches and are an important energy source that provides 4 kcal/g of energy.

Small molecules (called monosaccharides or disaccharides) and break down quickly.

Larger molecules (called polysaccharides) that break down more slowly, which causes slower release into the bloodstream and a slower increase in blood sugar over a longer period of time.

A measure of how quickly glucose levels increase in the bloodstream after carbohydrates are consumed.

Peptides and amino acids that provide 4 kcal/g of energy.

Reflects the equilibrium between protein intake and losses.

Have enough amino acids to perform necessary bodily functions, such as growth and tissue maintenance.

Do not contain enough amino acids to sustain life.

Have enough amino acids to sustain life, but not enough for tissue growth and maintenance.

Consist of fatty acids and glycerol and are essential for tissue growth, insulation, energy, energy storage, and hormone production.

Fats that come from animal products, such as butter and red meat (e.g., steak).

Fats come from oils and plants, although chicken and fish also contain some unsaturated fats.

Fats that have been altered through a hydrogenation process, so they are not in their natural state.

Vitamins not stored in the body, include vitamin C and B-complex vitamins.

Absorbed with fats in the diet and include vitamins A, D, E, and K.

Inorganic materials essential for hormone and enzyme production, as well as for bone, muscle, neurological, and cardiac function.

A type of mineral that is needed in larger amounts and are typically measured in milligrams, grams, or milliequivalents.

Minerals are needed in tiny amounts including zinc, iron, chromium, copper, fluorine, iodine, manganese, molybdemun, and selenium.

Include beans, grains, and fruits and vegetables but do not contain red meat, poultry, seafood, or other animal flesh.

A vegetarian diet that includes dairy products.

A vegetarian diet that includes dairy products and eggs.

The most restrictive vegetarian diet and does not include dairy, eggs, or other animal products.

Occurs when the body lacks an enzyme called lactase that breaks down lactose, the type of sugar in milk.

Refers to limited or uncertain access to nutritious foods because of social or economic factors.