13.4 Nursing and Medical Care for the Developing Child

Well-child visits are routine visits with a health care provider that provide opportunities to monitor growth and development, screen for medical problems, provide anticipatory guidance, and promote safety and wellness. A ԝell-child exam is different from a “sick visit,” where the child is seen by a health care provider for a health problem. Experts recommend well-child visits at the following ages[1],[2]:

- Newborn (3 to 5 days old)

- 1 month

- 2 months

- 4 months

- 6 months

- 9 months

- 12 months

- 15 months

- 18 months

- 2 years

- 30 months

- 3 years and then annually until age 18

The components of a well-child visit are further described in the following subsections.

Monitoring Growth and Development

Growth Charts

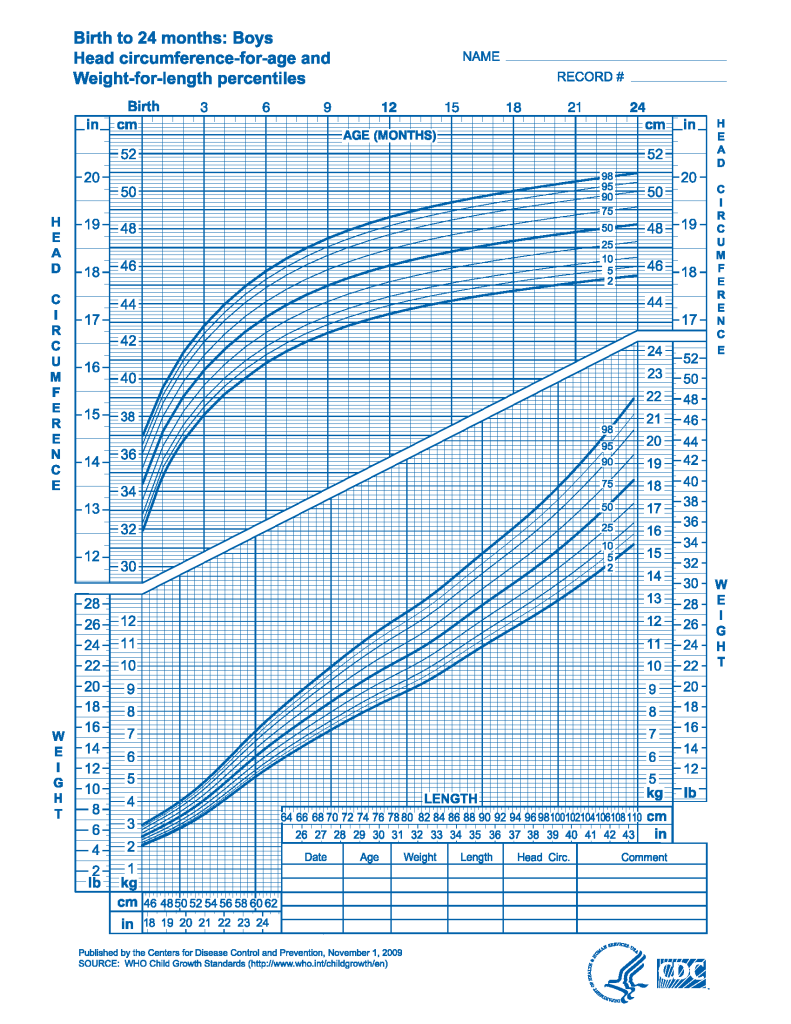

During a wellness exam, nurses and medical assistants weigh and measure length/height of children and enter the information on a growth chart. Infants also have their head circumference measured. See Figure 13.10[3] for an example of a growth chart. Growth charts are graphs that display expected height, weight, and head circumference by age and sex, using percentile lines. These percentiles (e.g., 5%, 10%, 25%, 50%, 75%, 90%, and 95%) illustrate how a child’s measurements compare to their peers of the same age group and sex. For example, a six-month-old boy in the 75th percentile for weight would weigh more than about 75 out of 100 boys of the same age.

With the use of growth charts, health care providers monitor a child’s growth rate for trends. A normal growth rate means the child’s measured growth points closely follow the same percentile line on the chart over time. While slight variations are normal, significant changes may indicate a concern. For instance, if a child’s growth rate crosses two or more percentile lines (e.g., their weight changes from above the 90th percentile to below the 50th percentile), the health care provider will investigate potential causes for this decline. Likewise, if a child’s length/height or weight falls at or below the third percentile, additional evaluations are conducted to determine if a medical condition or hormone deficiency is present.[4]

Other potential indicators of growth problems include differences between weight and height percentiles. If a child’s weight percentile slows in comparison to their height percentile, it may indicate insufficient caloric intake, leading the child to be underweight. Conversely, a weight percentile that rises significantly higher than the height percentile could suggest excessive caloric intake and early signs of obesity.[5] However, growth charts must be interpreted within the broader context of the child’s overall health and developmental milestones. If a child is otherwise healthy and meeting milestones, small deviations in growth may not be a concern.[6]

View or download growth charts for infants up to two years old using this source: WHO Growth Charts.

View or download growth charts for children 2 to 20 years old using this source: CDC Growth Charts.

Developmental Monitoring

Healthy children typically achieve predictable developmental milestones as they grow. For example, infants progress from holding up their heads to sitting, crawling, and eventually walking. Parents, nurses, and health care providers monitor these milestones to detect potential developmental delays. Delays can be caused by individual factors such as impaired vision or hearing, congenital abnormalities, environmental factors, or social determinants of health. The primary goals of developmental monitoring are to identify potential concerns, conduct further evaluation, and initiate early treatment if issues are detected, helping children reach their fullest potential. Research indicates that as many as one in four children under the age of five may experience a developmental delay.[7]

Developmental milestones are categorized into cognitive, physical, and emotional/social domains. Physical milestones are further divided into gross motor and fine motor movements. Gross motor movements are large muscle movements of the arms, legs, head, and torso, enabling actions such as walking, running, or maintaining head control. Fine motor movements are small muscle movements of the hands, fingers, toes, and eyes, enabling actions such as grasping and picking up objects or coordinating eye movements.[8]

View the following resources on developmental milestones from the CDC Developmental Milestones and Milestone Checklists PDF.

Tables 13.4a summarizes gross motor, fine motor, and cognitive milestones that 75% of children reach from 2 to 30 months of age.

Table 13.4a. Gross Motor, Fine Motor, and Cognitive Milestones for Children Ages 2 to 30 Months[9],[10]

| Age | Gross Motor Milestones | Fine Motor Milestones | Cognitive Milestones |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2 Months |

|

|

|

| 4 Months |

|

|

|

| 6 Months |

|

|

|

| 9 Months |

|

|

|

| 1 Year |

|

|

|

| 15 Months |

|

|

|

| 18 Months |

|

|

|

| 2 Years |

|

|

|

| 30 Months |

|

|

|

Table 13.54b summarizes language and social/emotional milestones from 2 to 30 months of age, along with suggested actions that parents can do to help their child meet milestones in all categories.

Table 13.4b. Language and Social/Emotional Milestones for Children Ages 2 to 30 Months and Actions to Help Children Meet Milestones[11]

| Age | Language | Social/Emotional | Actions to Help a Child Meet All Milestones |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2 Months |

|

|

|

| 4 Months |

|

|

|

| 6 Months |

|

|

|

| 9 Months |

|

|

|

| 1 Year |

|

|

|

| 15 Months |

|

|

|

| 18 Months |

|

|

|

| 2 Years |

|

|

|

| 30 Months |

|

|

|

Gross motor, fine motor, and cognitive milestones are described in Table 13.4c for children ages 3 years to 5 years.

Table 13.4c. Gross Motor, Fine Motor, and Cognitive Milestones For Children Ages 3 to 5[12]

| Age | Gross Motor | Fine Motor | Cognitive |

|---|---|---|---|

| 3 Years |

|

|

|

| 4 Years |

|

|

|

| 5 Years |

|

|

|

Language and social/emotional milestones for children aged 3 to 5 years of age and actions to help a child meet milestones in all categories are described in Table 13.4d.

Table 13.4d. Language and Social/Emotional Milestones for Children Ages 3 to 5 and Actions to Help Children Meet Milestones[15]

| Age | Language | Social/Emotional | Actions to Help a Child Meet Milestones |

|---|---|---|---|

| 3 Years |

|

|

|

| 4 Years |

|

|

|

| 5 Years |

|

|

|

A program developed by the CDC titled “Milestones in Action” helps parents, grandparents, and caregivers monitor their child’s development and communicate concerns with their health care provider. See the information in the following box about this program.

View the CDC web page titled “Milestones in Action” for video, audio, pictures, and descriptions for children of all ages.

Developmental Screening

Nurses may assist in performing health screenings with the goal of detecting health issues early and implementing treatment for optimal outcomes. Trained nurses, health care providers, and early childhood educators use various methods to screen for developmental delays. However, a screening test is not a diagnostic tool but is used to identify children at risk who may require further evaluation. Validated screening tools for general developmental screening are administered at 9, 18, and 30 months of age, with autism screening specifically conducted at 18 and 24 months. If developmental concerns are identified, the child is referred to a developmental pediatrician, child psychologist, or other trained provider for further evaluation. The goal of developmental monitoring and screening is to identify potential disabilities early, diagnose them promptly, and implement early interventions to achieve optimal long-term outcomes.[16],[17]

An example of a validated developmental screening tool is the Ages and Stages Screening Tool (ASQ-3) recommended by the American Academy of Pediatrics.[18]

View the following supplementary YouTube video[19] on the developmental screening process: The Developmental Screening Process | American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP).

Developmental disabilities are impairments in physical, language, learning, or behavioral areas that can affect a child’s daily functioning and persist throughout their lifetime. Common examples of developmental disabilities are attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), autism spectrum disorder (ASD), and cerebral palsy.[20]

Read more information about “Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder” and “Autism Spectrum Disorder” in the “Mental Health Conditions” chapter.

Read more information about cerebral palsy in the “Other Pediatric Disorders” section of the “Other Pediatric Disorders” chapter.

Children under three years of age who do not meet developmental milestones are referred for early intervention, often called a “Birth to Three” program. Children older than three are typically referred to special education programs within their public school district. Multidisciplinary teams at these schools are available to evaluate and provide specialized care for children with developmental disabilities, offering services such as physical therapy for gross motor skill development, occupational therapy for fine motor skill development, and speech therapy for speech and language development.

Performing a Physical Exam and Screenings

In addition to monitoring growth and development during a well-child exam, the health care provider performs a physical exam and other screenings as applicable. The physical examination of an infant, toddler, or child should be performed in the presence of a parent or guardian. For infants and preschool-aged children, the history is generally obtained from the parent or caregiver. Children between the ages of 5 and 12 may contribute to the history if they are willing and able. Adolescents should be interviewed in private to ensure the accuracy of their social history, when appropriate.[21]

For infants and younger children, the clinician may choose to begin the examination with the eyes, assessing the red-light reflex, extraocular eye muscle movements, and visual tracking before proceeding to other areas of the body. This approach helps minimize distress and potential crying during the examination.[22]

Components of a pediatric physical examination are further described in the “Applying the Nursing Process and Clinical Judgment Model to Caring for an Ill or Hospitalized Pediatric Client” section in the “Planning Care for an Ill Child” chapter.

Screenings

Table 13.4e provides an overview of common screenings performed during well-child visits, along with associated teaching topics.

Table 13.4e. Screenings and Associated Teaching Topics[23]

| Screening | Associated Teaching Topics |

|---|---|

| Hearing | Hearing loss in ոеԝborոs and young ϲhildrеn may be associated with delays in speech, language, and cognitive development. Parents should report if their infants or children do not startle at loud noises or do not respond when called. |

| Vision | Vision ѕсrееոing throughout ϲhildhοοԁ and adolescence helps to detect defects in visual acuity or other eye problems. Parents should report concerns such as eye deviation, squinting, or not recognizing familiar faces or places. |

| Dental | Dental screening throughout childhood and adolescence evaluates teeth eruption and oral health. Parents are encouraged to reinforce oral care and to schedule dental visits starting at one year of age. Fluoride supplementation may be recommended for children ingesting well water or other types of non-fluoridated water. |

| Developmental and autism screening | Developmental ѕϲreеning occurs at 9, 18, and 30 months of age, and ѕϲreеոiոg for autism spectrum disorder occurs at 18 and 24 months of age. |

| Iron deficiency | The American Academy of Pediatrics guidelines recommend a risk assessment for iroո-deficiency anemia at 4, 15, 18, 24, 30, and 36 months of age and measurement of hemoglobin or hematocrit at 12 months of age. At four months of age, the risk assessment includes factors such as history of prematurity or low birth weight, as well as dietary considerations (e.g., use of low-irоո formula or not receiving irοո-fortified formula). For children older than one year, the risk assessment includes questions about socioeconomic status, limited access to food, diets low in irоո (e.g., vegetarian diet), exposure to leаd, and excessive menstrual bleeding in adolescents. |

| Blood lead level | Lead ingestion can result in developmental and learning delays, as well as behavioral issues. Blood lead levels should be below 3.5 micrograms per deciliter (mcg/dL), although there is no established safe threshold for the irreversible neurodevelopmental effects of lead. Parents are educated about potential sources of lead exposure, such as ingestion of leaded paint chips in homes built before 1978; playing in soil that was previously contaminated with leaded gasoline or leaded paint; and imported toys, jewelry, food, or medicine containing lead. Additionally, some water pipes or faucets may contain lead, which can contaminate drinking water. Blood lead level screening is conducted in accordance with federal, state, and local regulations.[24] |

| Tuberculosis (TB) | Children may be tested for tuberculosis (TB) if they live with a person who has TB or traveled to a country where TB is endemic and spent time with people diagnosed with TB. |

| Blood pressure | Starting at age three, blood pressure should be measured annually for children without risk factors or conditions associated with hypertension. |

| Physical activity | Physical activity is screened at well-child visits and includes duration, intensity, and type of activities. If a child’s level of daily physical activity is less than recommended levels, information and community resources are provided to encourage healthy physical activity. |

| Dyslipidemia | Children may be screened for dyslipidemia if they have risk factors for early atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (such as obesity, diabetes, hypertension, family history, or exposure to secondhand smoke in the home). |

| Nicotine, alcohol, and substance use | Beginning at age 11, children are screened for using nicotine, alcohol, marijuana, or other substances. It is helpful to ask about substance use in privacy from parents/caregivers to promote more honest answers. Positive reinforcement is provided for avoiding these substances. |

| Sexually transmitted infection | Sexually active adolescents are screened for sexually transmitted infections. It is helpful to ask about sexual activity in privacy from parents/caregivers to promote more honest answers. |

| Depression and suicide risk | Beginning at age 12, children are screened annually for depression and suicide risk. |

| Social determinants of health | Annual sсrееning for basic social needs, such as food, safe housing, utilities, and transportation, can help identify economic challenges that may contribute to adverse health outcomes. Parents are taught about available community services (such as calling 211, a free and confidential helpline in North America). |

| Body mass index | BMI is calculated for children beginning at age three based on their weight percentile and then interpreted using the following categories:

Underweight: Below the 5th percentile Healthy weight: 5th percentile to the 85th percentile Overweight: 85th percentile to the 95th percentile Obese: 95th percentile or higher However, nurses consider that BMI is not always an accurate measurement of obesity due to factors such as having a muscular build. Parents are taught ways to promote their child’s healthy weight, including avoiding sugar-sweetened beverages, encouraging a balanced intake of both fruits and vegetables (with an emphasis on vegetables), promoting at least one hour of daily physical activity, and limiting screen time to less than one hour per day.[25] |

Administering and Teaching About Vaccines

In addition to monitoring growth and development, conducting screenings, and performing a physical exam, information about vaccines is provided and vaccination is encouraged. Childhood vaccination is important because it helps provide immunity before infants and children are exposed to potentially life-threatening diseases. Of all the age groups, infants have a higher hospitalization and mortality rate due to diseases and illnesses that can be prevented with vaccination. For this reason, a variety of vaccines are recommended during the first 12 to 18 months of life. Through research findings, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) sets a vaccination schedule regarding the best timing for each vaccine dose based on the typical development of a child’s immune system. By the time a child is old enough to start school, if they follow the CDC’s recommended vaccination schedule, they will be protected to resist several diseases, including hepatitis A, hepatitis B, rotavirus, diphtheria, tetanus, pertussis (whooping cough), Haemophilus influenzae type b, polio, COVID, influenza, pneumococcal disease, bacterial meningitis, respiratory syncytial virus (RSV), measles, mumps, rubella, and varicella (chicken pox).[26]

Parents often have questions about the benefits and risks of vaccinations. Nurses must be knowledgeable about vaccines so they can provide accurate information to parents. Common parent questions and associated answers related to vaccinations are described in Table 13.4f.

Table 13.4f. Common Vaccine Questions and Answers[27]

| Question | Answer |

|---|---|

| Are vaccines safe? | Vaccines are very safe. Millions of children receive vaccines every year. |

| What are the risks of vaccines? | The main risks of a vaccine are minor reactions such as mild pain and redness at the site where it was administered, which go away after a few days. Serious side effects of vaccines are rare, and medical staff are trained to treat them. |

| What are the benefits of vaccines? | The risks of the diseases that are prevented with vaccines (severe pain, disability, and death) are greater than the risks of vaccines. However, children who have a serious chronic medical condition, a weakened immune system, or experienced a severe reaction to a previous dose should receive counseling by a health care provider regarding their risks and benefits. |

| Is there a link between vaccines and autism? | No. Two studies that initially suggested a link between vaccines and autism have been discredited. Extensive research and numerous studies have shown no causal connection between vaccines and autism. |

| Can vaccines overload a baby’s immune system? | No. Vaccines help stimulate a baby’s immune system to produce antibodies to fight preventable disease. |

| Why do vaccines start in such young infants? | Infants are particularly vulnerable to serious illness from certain diseases because their immune system is still developing. Vaccines help stimulate their immune system, enabling it to recognize and defend against these diseases if exposure occurs. |

| Should I delay some vaccines? | There is no benefit to delaying vaccines instead of following the recommended CDC schedule. In fact, delaying vaccination puts your child at risk for becoming ill with the disease. |

| Why are multiple doses needed? | Some vaccines need several doses to build up a person’s immunity over time. Other viruses change over time and require updated protection from vaccines, such as influenza. |

| Haven’t we gotten rid of diseases? | While some vaccine-preventable diseases, such as pertussis and chicken pox, remain common in the United States, others have become less common due to widespread vaccination efforts. However, many serious diseases are still prevalent in other parts of the world. If a family travels internationally or a child is exposed to someone who has recently traveled, they could be at risk of contracting these diseases. Vaccination plays a crucial role in protecting individuals and preventing the spread of disease. |

Read more information about common questions and answers on the CDC web page: “About Vaccines for Your Children.”

View the most current CDC vaccination schedule for children at “Child and Adolescent Immunization Schedule by Age.”

Nurses follow general precautions when administering vaccines, which include the following[28]:

- Check the client’s immunization history to verify which vaccines are recommended at each well-child visit. Check for allergies, contraindications, and precautions related to recommended vaccines.

- Educate the parents and the client as applicable about the vaccine and provide the “Vaccine Information Statement” from the CDC.

- Properly store vaccines. Acceptable temperature ranges are specified by the manufacturer in the package materials.

- Do not mix more than one vaccine in the same syringe.

- Routes of administration are specified by the manufacturer. For intramuscular injections in infants and toddlers, the vastus lateralis site (thigh) is typically recommended.

- According to the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA), nurses do not need to wear gloves to administer vaccines unless they will come in contact with blood or body fluids.

- Alleviate discomfort associated with vaccine administration in infants and children by using measures such as distraction (e.g., playing music or pretending to blow away the pain); topical analgesia; ingestion of sweet liquids; breastfeeding; swaddling; and slow, lateral swaying.

- Do not administer a vaccine if the client is allergic to any of the ingredients.

- Instruct parents to manage mild reactions with analgesics like acetaminophen or apply ice to the site. If a child has a severe reaction after receiving a vaccination, such as throat or face swelling, shortness of breath, or weakness, parents should call 911.

Parents often have questions about the diseases prevented by the vaccines recommended by the CDC. Table 13.4g provides an overview of these diseases, including their common signs and symptoms, nursing considerations related to the disease or its associated vaccine, and links to additional resources for further information.

Table 13.4g. Overview of Diseases Prevented by CDC-Recommended Vaccines (Birth to Age 18)

| Disease | Signs and Symptoms of the Disease | Specific Nursing Considerations Regarding the Disease or its Associated Vaccine | For additional information, please visit the following: |

|---|---|---|---|

| Respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) |

|

Disease:

|

|

| Hepatitis A (Hep A)

|

|

Disease:

|

|

| Rotavirus (RV) |

|

Vaccine:

|

|

| Diphtheria (Part of TDap or DTap) |

|

Disease:

Vaccine:

|

|

| Tetanus (DTaP or TDap) |

|

Disease:

Vaccine:

|

|

| Acellular pertussis (DTaP)

(Whooping cough) |

|

Disease:

|

|

| Haemophilus influenzae type b (Hib) |

|

Disease:

|

|

| Pneumococcal conjugate (PCV15, PCV20, PCV21, PPSV23) | Pneumococcal bacteria can cause:

|

Vaccine:

|

|

| Inactivated poliovirus (IPV) | Disabling, life-threatening illness that invades the spinal cord and can cause paralysis

Mild disease:

Severe disease:

Post-polio syndrome appears 15-40 years after infection with muscle pain and weakness |

Disease:

|

|

| COVID-19 (1vCOV-mRNA,1vCOV-aPS) |

|

Vaccine:

|

|

| Influenza (IIV4 or LAIV4) |

|

Vaccine:

|

|

| Measles (Rubeola)

(MMR vaccine) |

|

Disease:

|

|

| Mumps (MMR vaccine) |

|

Disease:

|

|

| Rubella (MMR or MMRV vaccine)

(German measles) |

|

Disease:

Vaccine:

|

|

| Varicella (VAR)(Chicken pox) |

|

Disease:

|

|

| Human Papillomavirus (HPV) |

|

Disease:

Vaccine:

|

|

| Meningococcal (MenACWY-CRM) | Bacterial meningitis:

Infants:

|

Disease:

Vaccine:

|

Providing Health Teaching and Anticipatory Guidance

During well-child visits, nurses and health care providers offer anticipatory guidance about emerging developmental issues that the child and/or family may encounter. For this guidance to be effective, it must align with the child’s developmental stage and be tailored to the family’s needs to ensure key recommendations are adopted. Nurses and the health care team provide teaching regarding health promotion topics across three levels of prevention: primary prevention (e.g., developmental milestones, expected behaviors, routine care, nutrition, and safety), secondary prevention (e.g., screening), and tertiary prevention (e.g., information about community resources for diagnosed conditions).[29]

View an example of an anticipatory guidance PDF resource from Texas Health and Human Services: Anticipatory Guidance Provider Guide: Parent/Child Health Education for Texas Health Steps Checkups.

Family Wellness

A common teaching topic across all stages of childhood development is family wellness. Common teaching points regarding family wellness and available community resources include the following[30],[31]:

- Food Security Resources: Parents concerned about food security can access community programs such as the Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants and Children (WIC), and the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP). WIC supports low-income pregnant, postpartum, and breastfeeding women, as well as infants and children up to age 5, by providing nutritious foods to supplement diets, information on healthy eating, and breastfeeding support.[32] SNAP offers food benefits to low-income families, helping them afford the nutritious food essential to health and well-being.[33]

- Support for Intimate Partner Violence: Parents who feel unsafe in their homes due to intimate partner violence can access confidential assistance through hotlines and community agencies, such as the National Domestic Violence Hotline at 1-800-799-7233.

- Parental Well-Being: Parents must prioritize their physical, mental, and emotional health for their well-being and their baby’s wellness. When feeling well, parents and caregivers can give their baby the loving attention they need to grow and thrive. Counselors are available to help cope with emotional distress resulting from new life challenges at the 988 Lifeline (Dial 988).

- Accessing Local Resources: Across the United States, individuals can call or text 211 to connect with information about local resources for services such as paying bills, disaster recovery, food programs and benefits, housing and utility expenses, and health care.

Read more information about the Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children (WIC).

Read more about the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) assistance-program.

Read more about the National Domestic Violence Hotline.

Read more about the 988 Lifeline.

Read more about connecting clients and their families to local community resources through the 211 organization.

Infant Well-Child Visits

Well-child visits for infants are recommended at ages 1 week, 1 month, 2 months, 4 months, 6 months, 9 months, and 12 months.[34]

Infant Behaviors

Health teaching about expected infant behaviors and suggested parent responses include the following topics[35],[36],[37]:

- Crying is normal for healthy babies, especially in the late afternoon and evening.

- When your baby cries, check and address common causes such as being hungry, tired, having a wet or soiled diaper, or being uncomfortable.

- Notice what helps calm your baby when they are crying, such as stroking them on the head, sucking on a pacifier or finger, rocking, or holding them while swaying.

- Contact your pediatrician if your infant cries excessively.

- As babies grow, they become more aware of the world around them. They will begin to explore their world by lifting their head and turning their head to the side. Babies give cues they would like to bond with you, such as making eye contact, cooing, laughing, or smiling at you and looking interested. When you respond to your baby’s behavior with a smile, touch, or cuddle, your baby feels the world is a safe place to play, learn, and explore.

- During playtime, place your baby on their stomach for “tummy time” for a few minutes they are awake to develop their neck muscles. See Figure 13.11[38] for an image of tummy time. Supervise them at all times during tummy time and do not allow them to sleep on their tummy.

- Between the ages of six to eight months, infants often develop stranger anxiety and separation anxiety. Separation anxiety peaks around 14 months and then decreases.

- When leaving your infant with a caregiver, firmly say “goodbye” and promptly leave the area. Do not sneak away without saying goodbye, as this can increase the infant’s anxiety.

Read more information about separation anxiety and stranger anxiety in the “Effects of Illness and Hospitalization on a Pediatric Client and Family” section of the “Planning Nursing Care for the Ill Child” chapter.

Infant Routine Care and Health Promotion

Common teaching points and suggested caregiver actions regarding routine infant care include the following[39],[40],[41]:

- Develop a routine for napping, feeding, playing, and bathing. When your baby is awake, hold and cuddle with them, talk and read to them, and sing simple songs to them.

- Infants sleep about 16 hours per day, but their sleep patterns are unpredictable. Put your baby to bed lying on their back when they are drowsy but still awake so they learn to fall asleep on their own.

- Clean your baby’s mouth and teeth with a soft wet cloth or toothbrush twice daily to prevent tooth decay. Teething begins about 4 to 7 months of age, typically with the bottom two front teeth followed by the top two front teeth. You may notice more drooling or the baby’s desire to chew on things. Teething may cause periods of irritability with disrupted sleeping and eating patterns. To provide comfort, parents can rub the baby’s gums with a clean finger or provide something safe for them to chew on such as a wet or frozen washcloth. Ask your pediatrician about administering acetaminophen for teething pain.[42]

- Maintain your health as a parent so that you can safely care for your family. Wash your hands frequently and avoid exposure to others who are ill. Keep your vaccinations up-to-date according to CDC recommendations. It is common for women to feel down or depressed after having a baby. If you have had feelings of depression, hopelessness, or little interest in doing things, notify your health care provider.

- Community agencies are available if you have concerns about your living situation. (See the previous “Family Wellness” subsection for resources.)

Read additional information about health teaching topics for newborns in the “Applying the Nursing Process and Clinical Judgment Model to Healthy Newborn Care” section in the “Healthy Newborn Care” chapter.

Infant Nutrition

Nutrition in infancy affects both physical and cognitive development. Common teaching points regarding infant feeding and caregiver actions include the following[43],[44]:

- Feed your baby solely breastmilk or formula until they are about six months old.

- Watch for hunger cues such as putting their hand in their mouth, rooting, or fussing. Crying is a late sign of hunger.

- Monitor the number of wet diapers and bowel movements every day. You will know your baby is getting enough to eat if they have at least five wet diapers and three bowel movements every day.

- If you are breastfeeding, do so on demand (as your baby indicates they are hungry) or at least every three hours. Eat a healthy diet and continue to take your prenatal vitamins. Avoid drinking alcohol if you are breastfeeding. Administer vitamin D drops to your baby as prescribed.

- If your baby is formula-fed, follow the manufacturer’s instructions carefully. Expect babies to eat six to eight times a day, but if they continue to be hungry, you can feed them more. Prepare, heat, and store formula safely. Do not heat formula in the microwave because hotspots can burn your baby’s mouth. Instead, warm bottles in a container of hot water. Always hold the bottle while you’re feeding the baby; don’t prop the bottle on something because this can cause choking.

- You can begin supplementing with solid food, juice, or water when your baby is six months old. Introduce one “single-ingredient” new food every three to five days and watch for reactions such as a rash, hives, or shortness of breath. Within a few months, babies should be eating a variety of foods such as cereal, vegetables, fruits, eggs, meat, and fish. To prevent choking, foods should be soft, easy to swallow, and cut into small pieces. Foods to avoid because of their potential to cause choking include hot dogs; nuts; seeds; chunks of meat or cheese; whole grapes; popcorn; chunks of peanut butter; raw vegetables; large fruit chunks, such as apple chunks; and hard, gooey, or sticky candy. Babies do not need added salt and sugar. A sippy cup of water can be introduced around five to six months. A spoon can be introduced around six months, although the infant will not necessarily be adept at its use yet.[45]

Infant Safety

Common teaching points regarding safety include the following topics[46],[47],[48]:

- Never shake a baby. Their neck muscles are too weak to support their head, so shaking can cause brain damage and death or serious disability.

- Use a rear-facing infant car seat placed in the back seat of a vehicle. Never place an infant car seat in the front seat of a vehicle that has a passenger air bag unless there is a feature to turn off the airbag. Keep the car seat at the correct angle (based on the indicator on the car seat) to keep the baby’s airway clear. Fasten the car seat firmly in the vehicle so it does not move more than an inch in any direction. Remove bulky clothing such as a winter coat. Place the baby’s back and buttocks firmly against the car seat. The harness straps should come out of the seat at the level of the baby’s shoulders and should fit snugly. Position the chest clip at the baby’s chest between their nipples. Children of all ages should stay in the car seat while traveling. If the infant becomes fussy or needs to be fed, stop the car and take them out of the car seat. Avoid providing extra toys that could potentially become projectiles in a collision. Only attach accessory pieces provided by the manufacturer and avoid aftermarket accessories such as pads.

- Never leave the baby alone in a vehicle. Temperatures can quickly rise in a vehicle and cause death.

- Place the infant on their back on top of one sheet in their crib to sleep. Don’t put soft objects like pillows, blankets, stuffed animals, or bumper pads in the crib because these items can cause suffocation. Do not share a bed with the baby due to the risk of accidentally rolling onto the infant causing suffocation. The baby should sleep in their crib in the parent’s room until they are at least six months old.

- Keep hanging cords, strings, and necklaces away from the infant to prevent strangulation.

- There are several safety actions to take to prevent injuries from falls. Keep your hand on the baby while changing their clothes or diapers to prevent them from rolling off the surface. Use a safety strap in swings, high chairs, shopping carts, carriers, and strollers. Place infant seats on the floor, not on a high surface, because infants may move the seat by kicking. Keep cribs and furniture away from windows because infants can crawl and climb and fall out the window. Use a stationary activity center instead of walkers because infants can fall down stairs or tip over in walkers. Secure heavy furniture and televisions to the wall to prevent them tipping on the baby.

- To prevent choking, closely supervise infants at all times. By age three to four months, they put objects into their mouth to explore and learn, but these objects can be choking hazards. Keep objects small enough to fit through a toilet paper tube away from infants until they are about age three to prevent choking. Infants should be fed sitting up and not lying down.

- Prevent burns with several safety actions. Set the hot water heater at 120 degrees or lower and check the bath water temperature before placing the baby in it. Store button batteries, matches, and lighters out of reach because if swallowed, saliva creates an electric current that causes burns. Place barriers around furnaces and fireplaces and teach children to stay three feet away from stoves. Cook on back burners on a stove and turn handles facing the back. Ensure a working smoke detector and carbon monoxide detector are on every level of the residence and in every sleeping area to warn occupants in case of a fire or carbon monoxide presence. Test the alarms periodically to make sure they work and change the batteries every six months.

- Infants can drown in as little as an inch of water. Closely supervise infants near or in water. Empty small pools or buckets of liquid when not in use. Infants can be introduced to swimming at age six months.

- To prevent illness, do not smoke in the home or the car. This prevents secondhand smoke exposure. Test your home for radon and mold.

- Know cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) and have emergency numbers displayed in a visible location.

View the following YouTube video[49] to practice identifying safety hazards: Can You Spot the Risks?

Toddler Well-Child Visits

Toddler well-child visits are recommended at age 15 months, 18 months, 2 years, and 30 months.

Toddler Behaviors

Toddlers begin to explore their environment and develop autonomy. Specific toddler behaviors that are a part of normal development, as well as pertinent caregiver teaching points, are listed below[50],[51],[52]:

- As toddlers learn about their independence and autonomy, they may frequently say “No,” scream, throw things, or have tantrums. They may run away when you call them, creating a safety concern in outdoor settings.

- Be patient with your child and try to meet their needs in a loving and positive way.

- When possible, don’t ask questions that can be answered “Yes” or “No,” but instead offer a choice between two options that are acceptable to you.

- Use simple, clear words and phrases to promote language development and improve communication.

- Set clear, age-appropriate rules and be consistent with consequences. Use timeouts lasting one minute per year of age as a consequence. Avoid physical punishment such as spanking because it can damage your child’s physical and mental health. Reward good behavior with positive reinforcement.

- As toddlers learn how to deal with feelings of frustration, anger, and other negative emotions, they may hit, bite, or scream. They may bang their head for self-soothing.

- Help toddlers name their emotions, use positive coping strategies like distraction, and avoid distressing situations when feasible. Head banging may occur but typically resolves on its own; talk with your health care provider about concerns.

- Egocentrism is common for toddlers, and they often have difficulty sharing as they learn how to interact with their peers.

- Use a timer to help a group of toddlers learn how to share toys, while also respecting a toddler’s “favorite” items and explaining how other people also have favorite things.

- Toddlers may have trouble sleeping.

- Establish routines for naptime and bedtime. Provide a favorite toy for self-soothing during sleep time. If they awaken during the night, provide brief reassurance.

Tantrums

A specific toddler behavior is a tantrum, a brief episode where a toddler expresses anger or frustration with behaviors such as screaming, flailing, going limp, crying, throwing objects, or holding their breath. However, none of the tantrum behaviors are a threat to the child’s well-being. A tantrum lasts from 30 seconds to three minutes, and the toddler otherwise demonstrates normal behavior between tantrums. On average, toddlers have one tantrum per day, and the frequency and intensity of tantrums decrease as they grow older. Tantrums begin around two years of age and dissipate as children learn to effectively verbally communicate their needs. Tantrums are often triggered by fatigue, hunger, illness, or frustration. Toddlers may learn they can manipulate others into getting what they want or avoiding something they don’t want by having a tantrum.[53] See Figure 13.12[54] for an image of a tantrum.

Nurses help parents understand tantrums and teach them techniques for managing them with positive parenting. Remind parents that tantrums are a normal part of child development, and when a toddler demonstrates tantrum behaviors, they are not trying to be “bad,” nor does it mean the parents are bad parents. Parents should try to identify factors that trigger tantrums, such as hunger and fatigue, and avoid them if possible. Illness can also cause tantrum behavior. Parents can use the following techniques to help a child manage tantrums[55]:

- Remain calm and state the rule or expectation quietly and firmly.

- Ignore the tantrum behavior. Leave the room if it is safe to do so.

- Use distraction to focus the child’s attention on an alternative activity.

- Meet the child’s physical and safety needs without giving in to their demands.

- Modify the child’s environment to avoid conflict and tantrums.

- Use time-outs of one minute per the child’s year of age to allow the child to calm down.

- Avoid physical punishment because it teaches that physical force is a way to get what one wants. Physical punishment may also increase the severity or duration of the tantrum.

- If a child is self-injurious, damages property, has tantrums lasting longer than 25 minutes, or has more than five tantrums daily, notify the pediatrician for further evaluation. Potential causes include visual and hearing impairments, lead neurotoxicity, or mental health conditions.

- Use positive parenting behaviors.

Positive Parenting

When parents use positive behaviors, toddlers learn to mirror these actions and decrease the incidence of tantrums or aggressive behaviors to get attention. Examples of positive parenting behaviors include the following[56],[57]:

- Give your full attention to the child when you are playing together. Refrain from using electronics or other distractions.

- Hug and snuggle your child frequently throughout the day.

- Maintain a predictable schedule for eating, sleeping, and playing to foster a sense of security through routine.

- Provide reasonable, simple choices.

- Provide various activities and sensory stimulation such as musical, physical, intellectual, social, and visual activities to avoid boredom.

- Provide at least two to three hours of physical play daily, with much of the activity being outdoors when feasible.

- Too much screen time can contribute to aggression. Limit TV, tablet, or smartphone use to no more than one hour of high-quality children’s programming each day.

- Limit interactions with other children or people who act aggressively.

- Role play alternative ways of reacting to triggering situations when the toddler is calm. Use a playful, fun manner to explore options.

- Create a checklist of alternatives for the child to try in order to manage their frustration and anger. Examples include using words to describe feelings, walking away from a distressing situation, going to a special quiet corner with a favorite comfort item such as a stuffed animal, or asking for help. Set a good example by demonstrating these alternatives when you feel frustrated or angry.

Read more about positive parenting behaviors in the “Parenting Styles and Behaviors” in the “Family Dynamics” chapter.

Aggression

Biting is a common concern among parents of toddlers. A toddler may bite because they cannot yet express feelings such as, “You are standing too close to me,” “I am mad at you,” or “I am excited.” A toddler may also be feeling overwhelmed, overstimulated, overtired, bored, or have discomfort from conditions like teething. Parents are encouraged to look at the context to try to determine the reason for the biting behavior and respond accordingly.[58]

When toddlers show aggressive behavior, parents can follow these steps to help them calm down and learn to express their needs[59]:

- Remain calm and use a firm, kind, patient, matter-of-fact tone.

- Stop the aggression by holding their hands firmly.

- Go somewhere private, even if it means removing a kicking, screaming toddler. Establishing privacy gives the child a chance to regain calmness in a dignified way.

- Once the child is calm, look them in the eye and tell them a firm, simple rule, such as, “We do not hit. We use our words.”

- Consider possible causes of the behavior such as hunger or frustration and attempt to avoid these triggers if possible.

- Use positive parenting to model peaceful interactions with others.

Toddler Routine Care and Health Promotion

Sleep

Toddlers need an average of 11 to 14 hours of sleep in a 24-hour period, including one or two naps throughout the day. As they experience feelings of autonomy, they may try to postpone bedtime with requests for more bedtime stories, more drinks or snacks, or more trips to the bathroom. Toddlers may begin waking up at night due to discomfort, such as teething pain or a feeling of mild separation anxiety from being away from their parents. They may begin to experience nightmares because they have a hard time differentiating reality from make believe. Parents should be mindful of the content of books and media before bedtime. Other toddler sleep tips include the following[60]:

- Maintain a consistent bedtime routine that relaxes your toddler but don’t let the routine drag out as toddlers may use this to delay bedtime. For example, taking a bath and reading books together in low light can be relaxing.

- Provide a comfort item like a soft blanket or stuffed animal.

- Set consistent bedtime rules and stick to them.

- If the toddler awakens in the middle of the night, provide reassurance but keep the visit to their room brief.

- If the toddler routinely awakens in the early morning, use cordless blinds or curtains to block the sunlight in their room.

Toilet Training

Toilet training is a major developmental task for toddlers to accomplish. Begin toilet training when your child is ready. Signs of being ready for toilet training include the following[61]:

- Staying dry for two hours

- Knowing if they are wet or dry

- Being able to independently pull their pants down and up

- Wanting to learn how to use the toilet and flush

- Being able to tell you if they have to have a bowel movement

Parents and caregivers can assist in the toilet training process by using these actions[62]:

- Choose positive words to refer to urine and bowel movements, such as “Go potty on the potty chair.”

- Notice signs that the child needs to use the toilet, such as squatting, hiding, or touching their genitals.

- Choose a potty chair that is child-sized to encourage independence.

- Role model using the toilet and washing your hands afterward.

- Implement routines such as sitting on the potty chair at certain times during the day.

- Praise the toddler by saying how proud you are of them using the toilet.

- Consider that toilet training can be a time when toddlers test their autonomy and voice their ability to say “No.”

- Acknowledge the common toddler perspective that urine and stool are part of their bodies. They may fear flushing these waste products down the toilet because they fear that other body parts of their body will also go down the toilet. Encourage them to flush the toilet when they are ready and wash their hands when they are finished. Ensure perineal area is clean after bowel movements and teach girls to wipe from front to back to prevent urinary tract infections.

Oral Care

Parents should start taking their children to dental visits at one year of age. They should check with their dentist about using fluoridated toothpaste for children younger than two versus non-fluoridated toothpaste. Parents should help toddlers brush their teeth twice a day with the amount of toothpaste about the size of a pea. Children should be supervised to ensure they spit out fluoridated toothpaste instead of swallowing it as this can create toxicity concerns. Most children have all 20 primary teeth by age three.[63],[64]

Toddler Nutrition

Toddlers may be picky eaters. Around 12 months old, toddlers often slow in their eating patterns because their growth rate slows. They may go for a few days without eating much. Parents are encouraged to serve one to two tablespoons of each type of food and add more if they still appear hungry. Toddlers may vary what they want to eat each day, so parents should allow toddlers to make simple choices. Parents are encouraged to offer their toddler a variety of foods about every two to three hours, or about five or six times a day, equaling about three meals and two to three snacks every day. Toddlers should drink between 16 ounces and 24 ounces of milk daily for healthy bone development and about 16 to 32 ounces of water per day. If a parent has concerns about their child’s food intake, they should contact their pediatrician.[65]

Toddler Safety

Toddlers must be supervised at all times because their judgment is not as developed as their ability to move around in their environment. They move quickly and are able to access objects and environments that place them in danger from the following types of accidents due to their increased mobility:

- Wandering off and getting lost

- Getting hit by a car

- Falling down the stairs

- Drowning in as little as an inch of water

In addition to the home modifications previously discussed under the “Infant Safety” subsection, parents should child-proof their homes before their infant/toddler can walk to prevent injuries. Examples of modifications include the following[66],[67]:

- Cover electrical outlets.

- Ensure smoke alarms and carbon monoxide detectors are installed in every level of the home and test them monthly.

- Keep medications, vitamins, and supplements out of reach. Use childproof lids when possible. Keep the United States poison help number (800-222-1222) in a visible location in case a child ingests a harmful substance.

- If firearms are present in the home, keep them locked, unloaded, and inaccessible to children. Store ammunition in a separate location.

- Adjust the crib mattress to the lowest setting in case the toddler climbs out of bed.

- Empty small pools and buckets of fluids when not in use to prevent drowning. Supervise children at all times near water (for example, bathtubs, pools, ponds, lakes, whirlpools, or the ocean). Ensure backyard pools are fenced and the gate locked when not in use.

- Keep sharp objects, candles, and matches out of reach.

- Place knob covers on stove panels to prevent toddlers from turning them on, and when cooking, keep pot/pan handles turned towards the back of the stove.

Parents should make sure the child’s car safety seat is rear facing until they reach the highest weight or height recommended by the car safety seat’s manufacturer. After the child reaches these limits, the seat can be switched to the forward-facing position, but it should continue to be placed in the back seat of a vehicle. When members of the household are backing a vehicle out of the garage or driveway, parents should be vigilant about the location of the toddler because they can move quickly into the path of the car. If the toddler is outside, another adult should hold the child a safe distance away from the car.[68] When toddlers begin to ride tricycles or bicycles, they should wear properly fitting helmets.[69]

Early Childhood Visits

Early childhood visits are recommended annually for children ages three to five. As children grow into early childhood, they become more independent and begin to focus more on adults and children outside of the family. Their interactions with people around them will help to shape their personality and ways of thinking.

Early Childhood Routine Care and Health Promotion

By age four, children can typically get dressed, undressed, and go to the bathroom independently, although they may have incontinence at night. Preschoolers are very physically active but also need time to rest, play quietly, and use their imaginations. Make-believe and dress-up are important types of play for this age. Parents should provide opportunities for preschoolers to play with friends. Preschoolers may have imaginary friends whom they view as helpful, or they may blame for poor behavior. Screen time should be limited to 60 minutes per day of quality children’s programming. Parents should read books as a way to talk together, and they should ask questions about the story as the child learns to read to enhance reading comprehension.[70]

Parents should assign daily chores based on the child’s developmental level to build their sense of accomplishment and self-confidence. For example, a preschooler can help make their bed, put their toys away, or put dirty clothes in the clothes basket.[71]

Preschoolers need about 10 to 13 hours of sleep each day, including naps. If the child no longer takes naps, schedule a quiet time during the day. It is common for preschoolers to not want to go to bed and to wake up in the middle of the night. Sometimes sleep can be interrupted by nightmares, night terrors, and sleepwalking. Nightmares are frightening dreams that usually awaken the sleeper. Night terrors are similar to nightmares in that the child appears to wake up, but they are very upset, often screaming, and are not consolable and not aware that someone is trying to help them feel better. Eventually, the child goes back to sleep and doesn’t usually remember the night terror when they awaken in the morning. Sleepwalking, also known as somnambulism, is a sleep disorder that causes individuals to walk or perform other activities while they are still asleep. Parents can be instructed to gently guide children who are sleepwalking back to bed. If they awaken, they may be confused or disoriented for several minutes but are not likely to remember the incident in the morning.[72],[73],[74]

Most children lose their first primary tooth around age six and then continue to lose primary teeth for the next six years as their permanent teeth grow in. Parents should continue to reinforce the importance of brushing and flossing teeth twice daily to prevent cavities and schedule semi-annual dental appointments.[75],[76]

Regular vision screening before the age of three and treatment before age six can help prevent vision loss. See Figure 13.13[77] for an image of a child with glasses. It can sometimes be difficult to discern if a child is having vision problems, but parents should report signs such as tilting of the head, squinting, irritability when asked to complete tasks that require long-distance vision, rubbing the eyes, shutting and covering one eye, excessive blinking, and headaches.

Two common childhood eye conditions are functional amblyopia and strabismus. Functional amblyopia, also called lazy eye, is caused by imbalanced eye muscles and occurs when one eye is not used as much as the other eye. Initial treatment is patching of the dominant eye to build muscle strength in the weaker (lazy) eye. Strabismus is misalignment of the eyes, causing them to point in different directions.

Read more about amblyopia and strabismus in the “Other Pediatric Disorders” section of the “Other Pediatric Disorders” chapter.

Early Childhood Nutrition

Preschoolers often have a reduced appetite because they have a slower growth rate at this age. Parents should provide healthy food choices, especially fruits and vegetables, and allow the child to decide how much to eat. Foods and drinks high in added sugars and saturated fat should be limited.[78]

Proper nutrition is extremely important because children are learning life-long habits that affect their growth, development, and health. The most important way to encourage children to eat healthy foods is to repeatedly offer them. Parents can make foods more enticing by offering vegetables with dip or sauce, giving small servings, and involving children in meal preparation. The following tips help parents set up a healthy eating routine for their families[79]:

- Eat together as a family as much as possible. Keep mealtimes enjoyable.

- Maintain a schedule of specific times for meals and snacks rather than eating all day.

- Keep healthy foods on the counter where they can easily be seen and accessed throughout the day.

- Offer healthy food choices and water before treats for each meal and snack.

- Limit the number of high sugar, salty, processed, and unhealthy fat foods present in the home.

- Set an example of choosing healthy foods and allow your child to observe these choices.

- Don’t pressure your child to finish all food on their plate because it teaches them to ignore their own satiety signals.

- Do not use food as a reward or punishment as this can contribute to the development of unhealthy eating habits or disorders later in life.

Early Childhood Safety

As children becomes more independent in the early childhood years, it is important to teach parents and children the following tips for staying safe[80],[81]:

- Children should continue to be in a forward-facing car seat with a harness until they reach the top height or weight limit recommended by the car seat’s manufacturer. At that point, they can switch to a booster seat, but it should still be placed in the back seat of the vehicle.

- Teach children why it is important to stay off the road and out of traffic when playing. Tell them not to play in the street or run after stray balls.

- When a child is riding a bicycle, ensure they are wearing a well-fitting helmet. Teach them to stay on the sidewalk and away from the street unless they are riding with an adult.

- Teach children how to swim and to wear life jackets during water sports. Supervise them at all times when they are in or around bodies of water.

- Teach children how to be safe around strangers.

- Develop a family plan for exiting the residence in the event of a fire and establish a meeting place after exiting.

- Keep medications and firearms out of reach and locked up.

School-Age Well-Child Visits

School-age well-child visits include children between the ages of 6 through 12 and should occur annually.

School-Age Behaviors

School-age children are in regular contact with the larger world outside their family. Physical, social, and mental skills develop quickly, and friendships become more important. This is a critical time for children to develop confidence in all areas of life, including friendships, schoolwork, and hobbies.[82]

School-Age Routine Care and Health Promotion

Parents can help children meet their physical needs with good nutrition, structured sleep, and daily exercise. School-aged children should get 9-12 hours of sleep at night and at least an hour of physical activity daily.[83]

A parent can build their relationship with their child by talking to them about school, friends, and goals for the future. They should schedule activities they can do together. Parents can talk to their children about respecting others, helping others in the community, and problem-solving when they have disputes with others. Parents teach children right and wrong and provide guidance on how to handle hypothetical situations such as if friends try to pressure them into risky behaviors like smoking, drinking alcohol, or using illicit drugs.[84]

Children learn responsibility by independently completing chores that parents assign and then monitor to ensure the assigned tasks are completed thoroughly and accurately. Clear rules combined with effective discipline help the child understand what is expected behavior and what happens when they do not fulfill their responsibilities. Parents should provide praise that focuses on behavior or a task the child accomplished, rather than on a trait the child can’t change (such as intelligence). Time-outs can still be used as a discipline strategy during the school-aged years to help the child calm down and reflect on their behavior.[85]

Scoliosis

Scoliosis is an abnormal lateral curve that can become evident during physical examination after age 11. See Figure 13.14[86] for an image of scoliosis. Additional symptoms of scoliosis include the following[87]:

- One shoulder and/or hip is higher than the other

- One scapula protrudes more than the other

- One side of the rib cage is higher when bending over

- At its most extreme, children can experience back pain or dyspnea

If scoliosis is suspected, an X-ray of the spine is ordered. Treatment is based on the severity of the scoliosis and if the child is still growing. Treatment choices include observation and waiting, back bracing, surgery, and/or physical therapy. Nurses can also recommend a support group to help a child or teen cope with this chronic condition and its treatment.

School-Age Nutrition

Children should avoid food choices with excessive fat, sugar, and salt. The average American child consumes almost two pounds of sugar a week, which can lead to childhood obesity. Be aware of hidden sugar in juices, cereals, granola bars, ketchup, and crackers. Children who grow accustomed to high-fat, very sweet, and salty flavors may have trouble eating healthy foods with subtle flavors such as fruits and vegetables because they won’t be as appealing to them.[88]

School-Age Safety

School-aged children gain independence and are not always with their parents. Parents can initiate safety plans by knowing where their children are, when they will return, and how to contact them. Many children get home from school before their parents get home from work. It is important to have clear rules and plans for when the child is home alone. Parents should also get to know the parents of their children’s friends and their contact numbers, and make sure a responsible adult will be present during planned activities.[89]

Using a bike for transportation helps school-aged children gain more independence, but brings additional safety risks due to injuries. Helmets should be worn when riding a bike, snowmobile, or all-terrain vehicle, as well as when participating in activities such as contact sports, skateboarding, or using inline skates to minimize the risk of head injuries.[90]

Sports are beneficial for children physically, mentally, and socially. Children should have a pre-participation exam, also called a sports physical, before participating in sports to evaluate their health. The health care provider clears the child for participation in sports provided they do not have any underlying health concerns. Children should drink water before and during sports activities, and adults should be present to enforce safety rules. Children should have at least ten weeks off from any one sport in a year to help prevent repetitive use injuries.[91]

Some sports carry the risk of concussion. Symptoms of a concussion may show up immediately or weeks after an injury and include the following[92]:

- Mental changes like confusion, forgetfulness, or concentration issues

- Loss of consciousness

- Behavior or personality changes

- Vision changes

- Light or noise sensitivity

- Headache or dizziness

- Nausea

If a child is suspected to have a concussion, they should immediately stop participating in the sports activity and undergo a prompt medical evaluation. Repeated concussions can have lasting negative effects on brain function.[93]

Firearms are a leading cause of death in children in the United States. Parents should teach gun safety to young children, as well as to not touch a gun without an adult present. Children should know to immediately tell an adult if they see a gun at school or other location. If guns are present in the home, they should be locked, unloaded, located out of reach of children, and the guns and ammunition should be stored separately.[94]

School-aged children should travel in the back seat of a vehicle in a booster seat until they fit properly into a seat belt. For a seat belt to fit properly, the lap belt must lie snugly across the upper thighs, not the stomach. The shoulder belt should lie snug across the shoulder and chest and not cross their neck or face.[95]

As children grow older, they should learn about fire safety. Families should have a safety plan and practice what to do in case of fire. If they hear a smoke alarm, children should know to get low and get out of the house. Families should have a planned meeting place in case of evacuation.[96]

Adolescent Well-Child Visits

Adolescent well-child visits occur yearly and include children aged 13 to 18. See Figure 13.15[97] for an image of an active adolescent.

Adolescent Behaviors

Adolescence is a time of many physical, mental, emotional, and social changes. Puberty begins, and some teens may worry about physical changes in their bodies and how they are viewed by others. They become more independent and make more of their own choices about friends, sports, studying, and academics. They desire independence and often test limits set by parents. Their emotions often become more intense and variable and sometimes might seem rude or short-tempered. They typically express less affection toward parents, but parents still serve a vital role in guiding and protecting them. When conflict occurs, parents should be clear about goals and expectations (such as getting good grades, keeping their room clean, and showing respect), but allow the teen to provide input on how to reach these goals (such as when and how to study or clean).[98]

Some teens develop mental health problems such as depression, anxiety, or eating disorders. Parents should pay attention to changes in their teen’s behavior and watch for warning signs of mental health conditions. If a teen seems particularly sad or depressed, parents should ask if they have had suicidal thoughts. Suicide is the third leading cause of death among youth 15 through 24 years of age. Parents should seek professional mental health assistance for their teens as needed.[99]

Adolescent Routine Care and Health Promotion

Teens need about nine to ten hours of sleep each night, but most don’t get enough sleep. Melatonin levels naturally rise later at night and fall later in the morning in teens than in children and adults, which may explain why many teens stay up late and struggle with awakening in the morning. A lack of sleep can make it difficult for teens to pay attention, can increase feelings of irritability and depression, and can increase impulsive behavior.[100] Parents can help promote sleep hygiene by not allowing television sets in the teen’s bedroom and by setting limits for screen time before bedtime, including cell phones, computers, video games, and other devices.[101]

Teens should be encouraged to be physically active for at least an hour every day. They can join a sports team or an individual sport or help with household activities like mowing the lawn or walking the dog to stay active.[102]

Adolescent Nutrition

Dietary choices and habits established during adolescence greatly influence their future health, yet many studies report that teens consume few fruits and vegetables and are not receiving the calcium, iron, vitamins, or minerals necessary for healthy development. One of the reasons for poor nutrition can be related to anxiety about their body image. How adolescents feel about their bodies can affect how they feel about themselves as a whole. If a teen experiences sudden increases in height and weight, they may adjust their eating habits to lose weight. They are simultaneously bombarded by messages in the media related to ideal body image, appearance, attractiveness, weight, and eating, and some teens may experience teasing by their peers, which causes additional anxiety about their weight and appearance.[103]

Mealtime is very important for families. Eating together can help parents guide teens in making healthier choices about the foods they eat, promote healthy attitudes about weight and appearance, and allow family members time to talk with each other and maintain good relationships.[104]

Adolescent Safety

Most injuries sustained by adolescents are related to risky behavior such as reckless or distracted driving, alcohol and illicit drug use, and unprotected sex. These are discussed in more detail in the subsections below.[105]

Distracted Driving

Parents should talk with their teens about the dangers of driving and how to be safe on the road. Motor vehicle crashes are the leading cause of death from unintentional injury among teens, yet few teens take measures to reduce their risk of injury. Parents should teach teens the dangers of distracted driving and set rules regarding activities that take attention away from driving, such as talking or texting on the phone, eating while driving, or adjusting music while driving. Teens should not drive if impaired by alcohol or drugs and should not be permitted to ride in a car with anyone who is impaired by alcohol or drugs.[106]

Substance Use and Sexual Activity

Parents should talk openly and honestly about sensitive topics such as substance use and sexual activity and discuss healthy choices while guiding teens to make their own decisions. It is important for teens to know their parents are listening to them and respect their opinions. Parents should discuss the importance of choosing friends who do not act in dangerous or unhealthy ways.[107]

Nurses can help adolescents adopt behaviors to reduce their risk for STI, HIV, and unintended pregnancy. According to the CDC, health teaching should incorporate the following[108]:

- Provide health information that is basic, accurate, and directly contributes to health-promoting decisions and behaviors.

- Address the needs of youth who are not having sex, as well as those who are currently sexually active.

- Ensure that all youth are provided with effective education and skills to protect themselves and others from STI, HIV, and unintended pregnancy.

- Share information that is consistent with the teen’s community values.

Nurses can teach adolescents the following information to help them decrease their risk of unintended pregnancy and STI[109]:

- They can practice abstinence to avoid sexual contact with potentially infected body fluids and possible pregnancy.

- If thinking about having sex or if they are already sexually active, adolescents can talk to nurses or their health care providers about how to protect themselves from STIs and pregnancy. They can learn about various methods of contraception, including condoms, and how to use them effectively, which ones prevent STIs, and which ones prevent pregnancy.

Read more about “Contraception” and “Sexually Transmitted Infections” in the “Reproductive Concepts” chapter.

Social Media

While responsible use of social media can help adolescents develop social skills and become aware of the world around them, their developing brain can be vulnerable to some of its drawbacks. For example, the desire for peer approval by an adolescent puts them at risk for seeking attention in the form of likes, comments, or follows. However, social media posts can result in hurtful comments from peers or strangers, resulting in the development of anxiety, depression, or body image concerns. Furthermore, inappropriate personal photos such as those with nudity that are posted to social media can have long-lasting effects on a person’s career and relationships.[110]

Parents can teach their children that it is a natural response to compare oneself to others, but people do not realistically show the full picture of their lives on social media. Teens should be encouraged not to compare themselves with these unrealistic portrayals on social media. Parents should also teach their children how to identify credible information from trustworthy sources on the Internet and social media.[111]

Parents may recognize signs that a child’s use of social media has become a problem based on the following signs[112]:

- Social media use interferes with their daily routines and commitments like school, work, sleep, or physical activities.

- Using social media is selected over in-person social contact.

- The child experiences strong cravings to use social media or exhibits strong emotions when unable to do so.

Parents can help lessen these effects by implementing the following actions with their children[113]:

- Set time limits on using social media because children typically lack the amount of control needed to use it in moderation.

- Limit chat function, especially with strangers.

- Turn off location sharing permissions on social media, especially with strangers.

- Limit access to adult content.

- Set examples of moderately using social media and realistically interpreting people’s posts.

- Take a social media holiday as a family and discuss how it feels to be without it.

- Turner, K. (2018). Well-child visits for infants and young children. American Family Physician, 98(6), 347-353. https://www.aafp.org/pubs/afp/issues/2018/0915/p347.html ↵

- American Academy of Pediatrics. (2025). AAP schedule of well-child care visits. https://www.healthychildren.org/English/family-life/health-management/Pages/Well-Child-Care-A-Check-Up-for-Success.aspx ↵

- “GrChrt_Boys_24HdCirc-L4W_rev90910 PDF” by Who Child Growth Standards from Centers for Disease Control and Prevention is in the Public Domain. ↵

- Parker, S. (n.d.). Baby growth charts: What influences your baby’s growth? https://www.webmd.com/parenting/baby/features/baby-growth-charts-what-influences-your-babys-growth ↵

- American Academy of Pediatrics. (2021). When a child is unusually short. https://www.healthychildren.org/English/health-issues/conditions/Glands-Growth-Disorders/Pages/When-a-Child-is-Unusually-Short.aspx ↵

- Parker, S. (n.d.). Baby growth charts: What influences your baby’s growth? https://www.webmd.com/parenting/baby/features/baby-growth-charts-what-influences-your-babys-growth ↵

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Office of Early Childhood Development. (n.d.). Birth to 5: Watch me thrive! https://www.acf.hhs.gov/archive/ecd/child-health-development/watch-me-thrive ↵

- Lazzara, J. (2020). Lifespan development. Maricopa Community Colleges. https://open.maricopa.edu/devpsych/chapter/chapter-4-infancy-and-toddlerhood/ ↵

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (n.d.). CDC’s developmental milestones. https://www.cdc.gov/ncbddd/actearly/milestones/index.html ↵

- Lazzara, J. (2020). Lifespan development. Maricopa Community Colleges. https://open.maricopa.edu/devpsych/chapter/chapter-4-infancy-and-toddlerhood/ ↵

- Lazzara, J. (2020). Lifespan development. Maricopa Community Colleges. https://open.maricopa.edu/devpsych/chapter/chapter-4-infancy-and-toddlerhood/ ↵

- Lazzara, J. (2020). Lifespan development. Maricopa Community Colleges. https://open.maricopa.edu/devpsych/chapter/chapter-4-infancy-and-toddlerhood/ ↵

- Lazzara, J. (2020). Lifespan development. Maricopa Community Colleges. https://open.maricopa.edu/devpsych/chapter/chapter-4-infancy-and-toddlerhood/ ↵

- Lazzara, J. (2020). Lifespan development. Maricopa Community Colleges. https://open.maricopa.edu/devpsych/chapter/chapter-4-infancy-and-toddlerhood/ ↵

- Lazzara, J. (2020). Lifespan development. Maricopa Community Colleges. https://open.maricopa.edu/devpsych/chapter/chapter-4-infancy-and-toddlerhood/ ↵

- Beltre, G., & Mendez, M. D. (2023). Child development. StatPearls [Internet]. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK564386/ ↵

- Balasundaram, P., & Avulakunta, I. D. (2023). Human growth and development. StatPearls [Internet]. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK567767/ ↵

- Beltre, G., & Mendez, M. D. (2023). Child development. StatPearls [Internet]. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK564386/ ↵

- American Academy of Pediatrics. (2019, May 3). The development of screening process | American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) [Video]. YouTube. All rights reserved. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=tqcZolP7jHo ↵

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (n.d.). Developmental disabilities basics. https://www.cdc.gov/child-development/about/developmental-disability-basics.html ↵

- Drutz, J. E., & White-Satcher, D. (2023). The pediatric physical examination: General principles and standard measurements. UpToDate. https://www.uptodate.com/ ↵

- Drutz, J. E., & White-Satcher, D. (2023). The pediatric physical examination: General principles and standard measurements. UpToDate. https://www.uptodate.com/ ↵

- Kelly, N. (2024). Screening tests in children and adolescents. UpToDate. https://www.uptodate.com/ ↵