11 The Impact of Culture and Time on Business Ethics

Stephen M. Byars and Kurt Stanberry

Access this chapter for free at https://openstax.org/books/business-ethics/pages/5-introduction

Introduction

Ethics is a construct of considerable significance to human beings. Some suggest ethics emerged to allow families and clans to cooperate in harsh environments. Others point to its use in governing trade and commerce, even simple bartering. Still others say ethical behavior is wired into the cognitive structures of the brain, explaining why we find codes of ethics and morality in texts as diverse as the Code of Hammurabi (a Babylonian code of law nearly four thousand years old), the Bible, the Napoleonic Code, and The Analects of Confucius, all of which outline ways for people to live together in society.

Whatever its origin, ethics has almost certainly existed throughout human time and varied with language, culture, history, and geography. Are there underlying values that transcend time and place, however? If so, do the protocols of business ethics embody these values? For instance, we see respect for others in Dubai, where tea accompanies negotiations; in Tokyo, where formal words and bows come first; and in Lima, where polite inquiries about the family precede business. Is respect, therefore, a universal value?

In short, to what degree is any code of business ethics conditioned by culture, time, and geography? Given that individuals are responsible only for their own behavior, is it possible for business ethics to be universal?

The Relationship between Business Ethics and Culture

Learning Objectives

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Describe the processes of acculturation and enculturation

- Explain the interaction of business and culture from an ethical perspective

- Analyze how consumerism and the global marketplace might challenge the belief system of an organization

It has been said that English is the language of money and, for that reason, has become the language of business, finance, trade, communication, and travel. As such, English carries with it the values and assumptions of its native speakers around the world. But not all cultures share these assumptions, at least not implicitly. The sick leave or vacation policies of a British investment bank, for instance, may vary greatly from those of a shoe manufacturer in Laos. Because business and capitalism as conducted today have evolved primarily from European origins and profits are measured against Western standards like the U.S. dollar, the ethics that emerges from them is also beholden primarily (but not exclusively) to Western conceptions of behavior. The challenge for business leaders everywhere is to draw out the values of local cultures and integrate the best of those into their management models. The opportunities for doing so are enormous given the growing impact of China, India, Russia, and Brazil in global commerce. The cultures of these countries will affect the dominant business model, possibly even defining new ethical standards.

Business Encounters Culture

To understand the influence of culture on business ethics, it is essential to understand the concepts of enculturation and acculturation. In its most basic anthropological sense, enculturation refers to the process by which humans learn the rules, customs, skills, and values to participate in a society. In other words, no one is born with culture; all humans, regardless of their origin, have to learn what is considered appropriate behavior in their surrounding cultures. Whereas enculturation is the acquisition of any society’s norms and values, acculturation refers specifically to the cultural transmission and socialization process that stems from cultural exchange. The effects of this blending of cultures appear in both the native (original) culture and the host (adopted) culture. Historically, acculturation has often been the result of military or political conquest. Today, it also comes about through economic development and the worldwide reach of the media.

One of the earliest real estate deals in the New World exemplifies the complexity that results when different cultures, experiences, and ethical codes come into contact. No deed of sale remains, so it is difficult to tell exactly what happened in May 1626 in what is now Manhattan, but historians agree that some kind of transaction took place between the Dutch West India Company, represented by Pieter Minuit, the newly appointed director-general of the New Netherland colony, and the Lenape, a Native American tribe. Which exact Lenape tribe is unknown; its members may have been simply passing through Manhattan and could have been the Canarsee, who lived in what is today southern Brooklyn.

Legend has it that the Dutch bought Manhattan island for $24 worth of beads and trinkets, but some historians believe the natives granted the Dutch only fishing and hunting rights and not outright ownership. Furthermore, the price, acknowledged as “sixty guilders” (about $1000 today), could actually represent the value of items such as farming tools, muskets, gun powder, kettles, axes, knives, and clothing offered by the Dutch. Clearly, the reality was more nuanced than the legend.

The 1626 purchase of Manhattan as depicted by Alfred Fredericks in The Popular Science Monthly of 1909. (credit: “The Purchase of Manhattan Island” by “Ineuw”/Wikimedia Commons, Public Domain)

The “purchase” of Manhattan is an excellent case study of an encounter between two vastly different cultures, worldviews, histories, and experiences of reality, all within a single geographic area. Although it is a misconception that the native peoples of what would become the United States did not own property or value individual possession, it is nevertheless true that their approach to property was more fluid than that of the Dutch and of later settlers like the English, who regarded property as a fixed commodity that could be owned and transferred to others. These differences, as well as enforced taxation, eventually led to war between the Dutch and several Native American tribes. European colonization only exacerbated hostilities and misunderstandings, not merely about how to conduct business but also about how to live together in harmony.

Link to Learning

Two major conditions affect the relationship between business and culture. The first is that business is not culturally neutral. Today, it typically displays a mindset that is Western and primarily English-speaking and is reinforced by the enculturation process of Western nations, which tends to emphasize individualism and competition. In this tradition, business is defined as the exchange of goods and services in a dedicated market for the purpose of commerce and creating value for its owners and investors. Thus, business is not open ended but rather directed toward a specific goal and supported by beliefs about labor, ownership, property, and rights.

In the West, we typically think of these beliefs in Western terms. This worldview explains the misunderstanding between Minuit, who assumed he was buying Manhattan, and the tribal leaders, who may have had in mind nothing of the sort but instead believed they were granting some use rights. The point is that a particular understanding of and approach to business are already givens in any particular culture. Businesspeople who work across cultures in effect have entered the theater in the middle of the movie, and often they must perform the translation work of business to put their understanding and approach into local cultural idioms. One example of this is the fact that you might find sambal chili sauce in an Indonesian McDonald’s in place of Heinz ketchup, but the restaurant, nevertheless, is a McDonald’s.

The second condition that affects the relationship between business and culture is more complex because it reflects an evolving view of business in which the purpose is not solely generating wealth but also balancing profitability and responsibility to the public interest and the planet. In this view, which has developed as a result of political change and economic globalization, organizations comply with legal and economic regulations but then go beyond them to effect social change and sometimes even social justice.

The dominant manufacture-production-marketing-consumption model is changing to meet the demands of an increasing global population and finite resources. No longer can an organization maintain a purely bottom-line mentality; now it must consider ethics, and, therefore, social responsibility and sustainability, throughout its entire operation. As a result, local cultures are assuming a more aggressive role in defining their relationship with business prevalent in their regions.

Had this change taken place four centuries ago, that transaction in Manhattan might have gone a little differently. However, working across cultures can also create challenging ethical dilemmas, especially in regions where corruption is commonplace. A number of companies have experienced this problem, and globalization will likely only increase its incidence.

Cases from the Real World

If you were to do a top-ten list of the world’s greatest corruption scandals, the problems of Petrobras (Petróleo Brasileiro) in Brazil surely would make the list. The majority state-owned petroleum conglomerate was a party to a multibillion-dollar scandal in which company executives received bribes and kickbacks from contractors in exchange for lucrative construction and drilling contracts. The contractors paid Petrobras executives upward of five percent of the contract amount, which was funneled back into slush funds. The slush funds, in turn, paid for the election campaigns of certain members of the ruling political party, Partido dos Trabalhadores, or Workers Party, as well as for luxury items like race cars, jewelry, Rolex watches, yachts, wine, and art.

The original investigation, known as Operation Car Wash (Lava Jato), began in 2014 at a gas station and car wash in Brasília, where money was being laundered. It has since expanded to include scrutiny of senators, government officials, and the former president of the republic, Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva. The probe also contributed to the impeachment and removal of Lula’s successor, Dilma Rousseff. Lula and Rousseff are members of the Workers Party. The case is complex, revealing Chinese suppliers, Swiss bank accounts where money was hidden from Brazilian authorities, and wire transfers that went through New York City and caught the eye of the U.S. Department of Justice. In early 2017, the Brazilian Supreme Court justice in charge of the investigation and prosecution was mysteriously killed in a plane crash.

It is hard to imagine a more tragic example of systemic breakdown and individual vice. The loss of trust in government and the economy still affects ordinary Brazilians. Meanwhile, the investigation continues.

Critical Thinking

- Is there any aspect of the case where you think preventive measures could have been taken either by management or government? How would they have worked?

- Do you think this case represents an example of a culture with different business ethics than those practiced in the United States? Why or why not? How might corporations with international locations adjust for this type of issue?

Link to Learning

Balancing Beliefs

What about the ethical dimensions of a business in a developed country engaging in commerce in an environment where corruption might be more rampant than at home? How can an organization remain true to its mission and what it believes about itself while honoring local customs and ethical standards? The question is significant because it goes to the heart of the organization’s values, its operations, and its internal culture. What must a business do to engage with local culture while still fulfilling its purpose, whether managers see that purpose as profitability, social responsibility, or a balance between the two?

Most business organizations hold three kinds of beliefs about themselves. The first identifies the purpose of business itself. In recent years, this purpose has come to be the creation not just of shareholder wealth but also of economic or personal value for workers, communities, and investors.

The second belief defines the organization’s mission, which encapsulates its purpose. Most organizations maintain some form of mission statement. For instance, although IBM did away with its formal mission statement in 2003, its underlying beliefs about itself have remained intact since its founding in 1911. These are (1) dedication to client success, (2) innovation that matters (for IBM and the world), and (3) trust and personal responsibility in all relationships.

President and chief executive officer (CEO) Ginni Rometty stated the company “remain[s] dedicated to leading the world into a more prosperous and progressive future; to creating a world that is fairer, more diverse, more tolerant, more just.”

Link to Learning

Finally, businesses also go through the process of enculturation; as a result, they have certain beliefs about themselves, drawn from the customs, language, history, religion, and ethics of the culture in which they are formed. One example of a company whose ethics and ethical practices are deeply embedded in its culture is Merck & Co., one of the world’s largest pharmaceutical companies and known for its strong ethical values and leadership. As its founder George W. Merck (1894–1957) once stated, “We try to remember that medicine is for the patient. We try never to forget that medicine is for the people. It is not for the profits. The profits follow, and if we have remembered that, they have never failed to appear. The better we have remembered it, the larger they have been.” Culture is deeply rooted, but businesses may make their own interpretations of its accepted norms.

Link to Learning

Our beliefs are also challenged when a clash occurs between a legal framework and cultural norms, such as when a company feels compelled to engage in dubious and even illegal activities to generate business. For example, the German technology company Siemens has paid billions of dollars in fines and judgments for bribing government officials in several countries. Although some local officials may have expected to receive bribes to grant government contracts, Siemens was still bound by national and international regulations forbidding the practice, as well as by its own code of ethics. How can a company remain true to its mission and code of ethics in a highly competitive international environment?

Business performance is a reflection of what an organization believes about itself, as in the IBM and Merck examples. Those beliefs, in turn, spring from what the individuals in the organization believe about it and themselves, based on their communities, families, personal biographies, religious beliefs, and educational backgrounds. Unless key leaders have a vision for the organization and themselves, and a path to achieving it, there can be no balance of beliefs about profitability and responsibility, or integration of business with culture. The Manhattan purchase was successful to the degree that Minuit and the tribal leaders were willing to engage in an exchange of mutual benefit. Yet this revealed a transaction between two very different commercial cultures. Did each group truly understand the other’s perception of an exchange of goods and services? Furthermore, did the parties balance personal and collective beliefs for the greater good? Given the distinctions between these two cultures, would that even have been possible?

Consumerism and the Global Marketplace

To paraphrase the ancient Greek philosopher Heraclitus (c. 535–475 BCE), the one constant in life is change. Traditional norms and customs have changed as the world’s population has grown more diverse and urbanized, and as the Internet has made news and other resources readily available. The growing emphasis on consumerism—a lifestyle characterized by the acquisition of goods and services—has meant that people have become defined as “consumers” as opposed to citizens or human beings. Unfortunately, this emphasis eventually leads to the problem of diminishing marginal utility, with the consumer having to buy an ever-increasing amount to reach the same level of satisfaction.

At the same time, markets have become more diverse and interconnected. For example, South Korean companies like LG and Samsung employ 52,000 workers in the United States, and many U.S. companies now manufacture their products abroad. Such globalization of their domestic markets has allowed U.S. consumers to enjoy products from around the world, but it also presents ethical challenges. The individual consumer, for instance, may benefit from lower prices and a greater selection of goods, but only by supporting a company that might be engaged in unethical practices in its overseas supply or distribution chains. Producers’ choices about wages, working conditions, environmental impact, child labor, taxation, and plant safety feature in the creation of each product brought to market. Becoming aware of these factors requires consumers to engage in an investigation of the business practices of those parties they will patronize and exercise a certain amount of cultural and ethical sensitivity.

Cases from the Real World

How can the purchase of a pair of sneakers be seen as an ethical act? Throughout the 1990s, the U.S. shoe and sportswear manufacturer Nike was widely criticized for subcontracting with factories in China and Southeast Asia that were little more than sweatshops with deplorable working conditions. After responding to the criticisms and demanding that its suppliers improve their workplaces, the company began to redeem itself in the eyes of many and has become a model of business ethics and sustainability. However, questions remain about the relationship between business and government.

For instance, should a company advocate for labor rights, a minimum wage, and unionization in developing countries where it has operations? What responsibility does it have for the welfare of a contractor’s workers in a culture with differing customs? What right does any Western company have to insist that its foreign contractors observe in their factories the protocols required in the West? What, for example, is sacred about an eight-hour workday? When Nike demands that foreign manufacturers observe Western laws and customs about the workplace, arguably this is capitalist imperialism. Not only that, but Western firms will be charged more for concessions regarding factory conditions. Perhaps this is as it should be, but Western consumers must then be prepared to pay more for material goods than in the past.

Some argue that demanding that companies accept these responsibilities imposes cultural standards on another culture through economic pressure. Others insist there should be universal standards of humane employee treatment, and that they must be met regardless of where they come from or who imposes them. But should the market dictate such standards, or should the government?

The rise of artificial intelligence and robotics will complicate this challenge because, in time, they may make offshoring the manufacture and distribution of goods unnecessary. It may be cheaper and more efficient to bring these operations back to developed countries and use robotic systems instead. What would that mean for local cultures and their economies? In Nike’s case, automation is already a concern, particularly as competition from its German rival, Adidas, heats up again.

Critical Thinking

- What ethical responsibilities do individual consumers have when dealing with companies that rely on overseas labor?

- Should businesses adopt universal workplace standards about working conditions and employee protections? Why or why not?

- What would be required for consumers to have the necessary knowledge about a product and how it was made so that they could make an informed and ethical decision? The media? Commercial watchdog groups? Social-issues campaigns? Something else?

Link to Learning

In considering the ethical challenges presented by the outsourcing of production to lower costs and increase profits, let us return to the example of IBM. IBM has a responsibility to provide technology products of high quality at affordable prices in line with its beliefs about client success, innovation, and trust. If it achieved these ends in a fraudulent or otherwise illegal way, it would be acting irresponsibly and in violation of both U.S. and host country laws and as well as the company’s own code of ethics. These constraints appear to leave little room for unethical behavior, yet in a globalized world of intense competition, the temptation to do anything possible to carve out an advantage can be overpowering. This choice between ends and means is reminiscent of the philosophers Aristotle and Kant, both of whom believed it impossible to achieve just ends through unjust means.

But what about consumer responsibility and the impact on the global community? Western consumers tend to perceive globalization as a phenomenon intended to benefit them specifically. In general, they have few compunctions about Western businesses offshoring their manufacturing operations as long as it ultimately benefits them as consumers. However, even in business, ethics is not about consumption but rather about human morality, a greater end. Considering an expansion of domestic markets, what feature of this process enables us to become more humane rather than simply pickier consumers or wasteful spenders? It is the opportunity to encounter other cultures and people, increasing our ethical awareness and sensitivity. Seen in this way, globalization affects the human condition. It raises no less a question than what kind of world we want to leave to our children and grandchildren.

Culture has a tremendous influence on ethics and its application in a business setting. In fact, we can argue that culture and ethics cannot be separated, because ethical norms have been established over time by and make sense to people who share the same background, language, and customs. For its part, business operates within at least two cultures: its organizational culture and the wider culture in which it was founded. When a business attempts to establish itself in a new environment, a third culture comes into play. With increasingly diverse domestic and global markets and the spread of consumerism, companies must consider the ethical implications of outsourcing production and resist the temptation to look the other way when their values are challenged by the reality of overseas supply or distribution chains.

- acculturation

- the cultural transmission and socialization process that stems from cultural exchange

- consumerism

- a lifestyle characterized by the acquisition of goods and services

- enculturation

- the process by which humans learn the rules, customs, skills, and values to participate in a society

Business Ethics over Time

Learning Objectives

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Describe the ways ethical standards change over time

- Identify major shifts in technology and ethical thinking over the last five hundred years

- Explain the impact of government and self-imposed regulation on ethical standards and practices in the United States

Besides culture, the other major influence in the development of business ethics is the passage of time. Ethical standards do not remain fixed; they transform in response to evolving situations. Over time, people change, technology advances, and cultural mores (i.e., acquired culture and manners) shift. What was considered an appropriate or accepted business practice one hundred or even fifty years ago may not carry the same moral weight it once did. However, this does not mean ethics and moral behavior are relative. It simply acknowledges that attitudes change in relationship to historical events and that cultural perspective and the process of acculturation are not stagnant.

Shifts in Cultural and Ethical Standards

We find an example of changing cultural mores in the fashion industry, where drastic evolution can occur even over ten years, let alone a century. The changes can be more than simply stylistic ones. Clothing reflects people’s view of themselves, their world, and their values. A woman in the first half of the twentieth century might be very proud to wear a fox stole with its head and feet intact ([link]). Today, many would consider that an ethical faux pas, even as the use of fur remains common in the industry despite active campaigns against it by organizations such as People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals. At the same time, cosmetics manufacturers increasingly pledge not to test their products on animals, reflecting changing awareness of animals’ rights.

Bias is built into the human psyche and expressed through our social structures. For this reason, we should avoid making snap judgments about past eras based on today’s standards. The challenge, of course, is to know which values are situational—that is, although many values and ethics are relative and subjective, others are objectively true, at least to most people. We can hardly argue in favor of slavery, for example, no matter in which culture or historical era it was practiced. Of course, although some values strike us as universal, the ways in which they are interpreted and applied vary over time, so that what was once acceptable no longer is, or the reverse.

Ethics Across Time and Cultures

From the 1940s to the 1970s, cigarettes were as common as water bottles are today. Nearly everyone smoked, from judges in court to factory workers and pregnant women. Edward Bernays, the Austrian-American founder of the field of public relations, promoted smoking among women in a 1929 campaign in New York City in which he marketed Lucky Strike cigarettes as “torches of freedom” that would lead to equality between men and women. However, by the late 1960s, and in the wake of the release of the landmark Surgeon General’s report on “Smoking and Health” on January 11, 1964, it had become clear that there was a direct link between cigarette smoking and lung cancer. Subsequent research has added heart and lung diseases, stroke, and diabetes. Smoking has decreased in Western countries but remains well established in the global East and South, where cigarette manufacturers actively promote the products in markets like Brazil, China, Russia, and Singapore, especially among young people.

Critical Thinking

Are such practices ethical? Why or why not?

Link to Learning

Thus, we acknowledge that different eras upheld different ethical standards, and that each of these standards has had an impact on our understanding of ethics today. But this realization raises some basic questions. First, what should we discard and what should we keep from the past? Second, on what basis should we make this decision? Third, is history cumulative, progressing onward and upward through time, or does it unfold in different and more complicated ways, sometimes circling back upon itself?

The major historical periods that have shaped business ethics are the age of mercantilism, the Industrial Revolution, the postindustrial era, the Information Age, and the age of economic globalization, to which the rise of the Internet contributed significantly. Each of these periods has had a different impact on ethics and what is considered acceptable business practice. Some economists believe there may even be a postglobalization phase arising from populist movements throughout the world that question the benefits of free trade and call for protective measures, like import barriers and export subsidies, to reassert national sovereignty. In some ways, these protectionist reactions represent a return to the theories and policies that were popular in the age of mercantilism.

Unlike capitalism, which views wealth creation as the key to economic growth and prosperity, mercantilism relies on the theory that global wealth is static and, therefore, prosperity depends on extracting wealth or accumulating it from others. Under mercantilism, from the sixteenth to the eighteenth centuries, the exploration of newly opened markets and trade routes coincided with the impulse to colonize, producing an ethical code that valued acculturation by means of trade and often brute force. European powers extracted raw commodities like cotton, silk, diamonds, tea, and tobacco from their colonies in Africa, Asia, and South America and brought them home for production. Few questioned the practice, and the operation of business ethics consisted mainly of protecting owners’ interests.

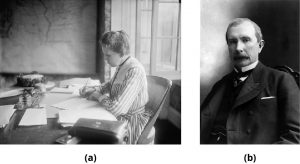

During the Industrial Revolution and the postindustrial era, in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, business focused on the pursuit of wealth, the expansion of overseas markets, and the accumulation of capital. The goal was to earn as high a profit as possible for shareholders, with little concern for outside stakeholders. Charles Dickens (1812–1870) famously exposed the conditions of factory work and the poverty of the working class in many of his novels, as did the American writer Upton Sinclair (1878–1968). Although these periods witnessed extraordinary developments in science, medicine, engineering, and technology, the state of business ethics was perhaps best described by critics like Ida Tarbell (1857–1944), who said of industrialist John D. Rockefeller (1839–1937), “Would you ask for scruples in an electric dynamo?”

With the advent of the Information and Internet ages in the late twentieth and early twenty-first centuries, a code of professional conduct developed for the purpose of achieving goals through strategic planning. In the past, ethical or normative rules were imposed from above to lead people toward right behavior, as the company defined it. Now, however, more emphasis is placed on each person at a firm embracing ethical standards and following those dictates to arrive at the appropriate behavior, whether at work or when off the clock.

The creation of human resources departments (increasingly now designated as human capital or human assets departments) is an outgrowth of this philosophy, because it reflects a view that humans have a unique value that ought not be reduced simply to the notion that they are instruments to be manipulated for the purposes of the organization. Millennia earlier, Aristotle referred to “living tools” in a similar but critical way. Although one characteristic of the information age—access to information on an unprecedented scale—has transformed business and society (and some say made it more egalitarian), we must ask whether it also contributes to human flourishing, and to what extent business should concern itself with this goal.

A Matter of Time

What effect does time have on business ethics, and how is this effect achieved? If we accept that business today has two purposes—profitability and responsibility—we might assume that business ethics is in a much better position now than in the past to affect conduct across industries. However, much of the transformation of business over time has been the result of direct government intervention; one recent example is the Dodd–Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act that followed the financial crisis of 2008. Yet, despite such regulation and increased management vigilance in the form of ethics training, compliance reporting, whistleblower programs, and audits, it is tempting to conclude that business ethics is in worse shape than ever. The Information Age and the Internet may even have facilitated unethical behavior by making it easier to move large sums of money around undetected, by enabling the spread of misinformation on a global scale, and by exposing the public to the theft and misuse of vast stores of personal data gathered by companies as diverse as Equifax and Facebook.

However, since the mercantile era, there has been a gradual increase in awareness of the ethical dimension of business. As we saw in the preceding chapter, businesses and the U.S. government have debated and litigated the role of corporate social responsibility throughout the twentieth century, first validating the rule of shareholder primacy in Dodge v. Ford Motor Company (1919) and then moving away from a strict interpretation of it in Shlensky v. Wrigley (1968). In Dodge v. Ford Motor Company (1919), the Michigan Supreme Court famously ruled that Ford had to operate in the interests of its shareholders as opposed to its employees and managers, which meant prioritizing profit and return on investment. This court decision was made even though Henry Ford had said, “My ambition is to employ still more men, to spread the benefits of this industrial system to the greatest possible number, to help them build up their lives and their homes. To do this we are putting the greatest share of our profits back in the business.” By mid-century and the case of Shlensky v. Wrigley (1968), the courts had given boards of directors and management more latitude in determining how to balance the interests of stakeholders. This position was confirmed in the more recent case of Burwell v. Hobby Lobby (2014), which held that corporate law does not require for-profit corporations to pursue profit at the expense of everything else.

Governmental regulation and legal interpretations have not been the only avenues of change over the past century. The growing influence of consumers has been another driving force in recent attempts by businesses to self-regulate and voluntarily comply with global ethical standards that ensure basic human rights and working conditions. The United Nations (UN) Global Compact is one of these standards. Its mission is to mobilize companies and stakeholders to create a world in which businesses align their strategies and operations with a set of core principles covering human rights, labor, the environment, and anticorruption practices. The Global Compact is a “voluntary initiative based on CEO commitments to implement universal sustainability principles and to undertake partnerships in support of UN goals.” Of course, as a voluntary initiative, the initiative does not bind corporations and countries to the principles outlined in it.

Link to Learning

Whenever we look at the ways in which our perception of ethical business practice changes over time, we should note that such change is not necessarily good or bad but rather a function of human nature and of the ways in which our views are influenced by our environment, our culture, and the passage of time. Many of the examples discussed thus far illustrate a gradual increase in social awareness due to the actions of individual leaders and the historical era in which they found themselves. This does not mean that culture is irrelevant, but that human nature exists and ethical inclination is part of that nature. Historical conditions may allow this nature to be expressed more or less fully. We might measure ethical standards according to the degree they allow human compassion to direct business practice or, at least, make it easier for compassion to hold sway. We might then consider ethics not just a nicety but a constitutive part of business, because it is an inherent human trait. This is a perspective Kant and Rawls might have agreed with. Ethical thinking over time should be measured, deliberate, and open to examination.

As a function of culture, ethics is not static but changes in each new era. Technology is a driving force in ethical shifts, as we can see in tracing changes from the age of mercantilism to the Industrial Revolution to the postindustrial era and the Information Age. Some of the most successful recent efforts to advance ethical practices have come from influences outside industry, including government regulation and consumer pressure.

- mercantilism

- the economic theory that global wealth is static and prosperity comes from the accumulation of wealth through extraction of resources or trade

The Influence of Geography and Religion

Learning Objectives

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Describe the impact of geography on global relationships and business ethics

- Explain how religion informs ethical business practice around the world

Business ethics guides people to practice commerce professionally and honestly and in a way that permits as many as possible to flourish. However, as we have seen, the ethical standards by which business is conducted can vary depending on culture and time. Geography and regional cultural practices also play a significant role. As global markets become increasingly connected and interdependent, we navigate more of our valued relationships across international boundaries.

Business as Global Relationships

Global relationships teach us to be sensitive not just to other languages and customs but also to other people’s worldviews. A company looking to move its production to another country may be interested in setting up supply, distribution, and value chains that support human rights, worker safety, and equity for women, while the local culture is excited about the economic benefits it will gain from the company’s investment in employment and the local tax base and infrastructure. These goals need not be in conflict, but they must be integrated if the company is to reach an ethically sound agreement with the host country. Dialogue and openness are crucial to this process, just as they are in every other kind of relationship.

Geography affects a business’s relationship with almost any type of stakeholder, from stockholders and employees to customers, the government, and the environment. Hence the growing importance of localization, the process of adapting a product for non-native environments and languages, especially other nations and cultures. Such adaption often starts with language translation but may include customizing content or products to the tastes and consumption habits of the local market; converting currencies, dates, and other measurements to regional standards; and addressing community regulations and legal requirements.

Research has shown that successful leaders and organizations with global responsibilities “need to understand and exceed the leadership expectations in the cultures they are interacting with.” In its study of leadership effectiveness and organizational behavior across cultures, the GLOBE leadership project of the Beedie School of Business at Simon Fraser University in Vancouver, Canada, found leader effectiveness is contextual and strongly connected to cultural and organizational values. The study also concluded that, although leaders learn to adapt to cultural expectations, they often have to exceed those expectations to be truly successful. In other words, business has a role beyond merely reflecting the culture in which it operates.

One element of business culture you may not realize is based on local custom and culture is the notion of time. Unlike the notion of historical time discussed in the previous module, the concept of time in business—people’s approach to punctuality, for example—varies widely in different cultures. To put it in economic terms, all cultures share the resource of time, but they measure and use that resource very differently. These differences might significantly affect the foundation of any business relationships you may want to establish around the world. For this and many other reasons, basic cultural literacy must be at the forefront of any ethical system that governs business behavior.

Consider, for example, that in the United States, we might speak of “a New York minute,” “the nick of time,” “the eleventh hour,” and so on. Such expressions make sense in a culture where the enculturation process emphasizes competition and speed. But even among Western business cultures, conceptions of time can differ. For example, the Italian subito and the German sofort both refer to something happening “at once” or “straightaway,” but with different expectations about when the action, in fact, will take place. And some cultures do not measure the passage of time at all.

Generally, the farther east and south we travel from the United States, the more time becomes relational rather than chronological. In Kenya, tutaonana baadaye means “see you later,” although “later” could be any time, open to context and interpretation. The nomadic inhabitants of North Africa known as the Tuareg sit down to tea before discussing any business, and as a rule, the longer the time spent in preliminary conversation, the better. A Tuareg proverb has it that the first cup of tea is bitter like life, the second sweet like love, and the third gentle like death. Compare this with the Western attitude that “time flies” and “time is money.” Finally, Westerners doing business in some English-speaking African countries have learned that if they want something immediately, they have to say “now now” as “now” by itself does not convey the desired sense of immediacy.

Another aspect of international business relationships is the question of personal space. In Nigeria, for example, standing either too close or too far from someone to whom you are speaking might be seen as impolite. In some cultures, touch is important in establishing connection, whereas in others it may be frowned upon. As a general rule, “contact” cultures—where people stand closer together when interacting, touch more often, and have more frequent direct eye contact—are found in South America, the Middle East, and southern Europe, while “noncontact” cultures—where eye contact and touching are less frequent, and there is less physical proximity during interactions—are in northern Europe, the Far East, and the United States. So, the seemingly innocuous gesture of a handshake to cement a new business relationship might be viewed very differently depending on where it occurs and who is shaking hands.

All of this speaks to the awareness and cultural sensitivity that must be exhibited by an ethical manager doing business in a region different from his or her own. Certain mistakes, particularly accidental ones and those not motivated by malicious design, will likely be forgiven. Still, a global ethical demeanor requires that we be as conscious as possible as to what constitutes courtesy wherever we find ourselves conducting business.

What Would You Do?

Time and space are just two examples of cultural characteristics that you may take for granted but that are not universal. Business attire is another, as is humor, which is notoriously hard to translate across languages and cultures. And, of course, miscommunications can occur not just across regional boundaries and business cultures but even within them. For example, unless you are a barista at a hipster coffee bar, it may not be a good idea to wear piercings, tattoos, or colorfully dyed hair to work. Employers have the right to establish a dress code and expect employees to abide by it.

In the movie The Intern, Robert De Niro’s senior character wears conservative blue and gray suits to his job at an e-commerce fashion startup, whereas the younger men dress very casually. At one point in the film, De Niro’s character asks, “Doesn’t anybody tuck in their shirt?” Leaving your shirt untucked has become more acceptable in recent years, and the black t-shirt and jeans favored in Silicon Valley are now quite fashionable in some business environments.

Many today would disagree with the old adage that “clothes make the man,” yet studies show that well-dressed employees are held in higher esteem and may earn more, on average, than those who dress down. The age of uncomfortable dresses and starched white shirts may be over, but cultural standards, along with underlying values that prioritize, say, innovation over uniformity, change over time and even within the same company.

Critical Thinking

- How do you think clothing choices affect the relationships we form at work or in other business situations?

- What is your opinion about workplace dress codes, and how far should employers go in setting dress and other behavior standards? Why are these standards important (or not) from an ethical perspective?

- How do you think clothing might affect an international company’s approach to business ethics?

Link to Learning

Religion and Ethics

A major factor in the difference that geography and culture make in our ethical standards is the influence of religious practice. For example, just as the current debate over the redistribution of goods and services has Christian roots, so the Industrial Revolution in England and northern Europe looked to Protestant Christianity in particular for the values of frugality, hard work, industriousness, and simplicity. Until the seventeenth century, religion and ethics were nearly inseparable. Many believed that people could not be persuaded to do the right thing without the threat of eternal damnation. The Enlightenment’s attempt to peel religion away from ethics was short-lived, with even Kant acknowledging the need to base morality on something beyond the rationalism of his time.

Religions are neither uniform nor monolithic, of course, nor are they unchanging over time. The core of Christianity, for instance, does not change, but its emphasis in any given period does. Moreover, the state or crown often worked side by side with the church in the past, choosing certain teachings over others to promote its own interests. This cooperation was evident during the era of mercantilism when the issue of personhood, or the privilege of having the freedom and capacity to make decisions and act morally, was hotly debated in the context of slavery, a practice that had been going on for centuries in the Christian West and the Islamic East. Although the church officially opposed slavery, the conquest of new lands was justified theologically as bringing salvation and civilization to populations considered savage and unsophisticated. Christianity was thought to save them from their pagan ways just as Islam and the message of the prophet saved unbelievers in the East. Behavioral norms for the clergy were founded and supported by the divine right of kings and the authority of religious tradition. Commerce and trade followed these norms.

By the time of the Industrial Revolution and postindustrial eras, Protestantism and its values of frugality, hard work, and simplicity (the “Protestant ethic”) had helped create a culture of individualism and entrepreneurship in the West, particularly in Great Britain and the United States. In fact, the Protestant work ethic, religion, and a commitment to hard work all are intertwined in the business history of both these countries. One example of this singular association is John D. Rockefeller, who, in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, commanded the attention given today to Bill Gates and Warren Buffet as emblems of free enterprise.

No one was more convinced of the link between religious faith and success in business than Rockefeller, who clung to his Baptist faith from his early years until his death in 1937. The richest person of his age, Rockefeller earned his fortune as the founder and major shareholder of Standard Oil but always regarded his billions as a public trust rather than his personal prize. “As his fortune grew big enough to beggar the imagination, [Rockefeller] retained his mystic faith that God had given him money for mankind’s benefit . . . or else why had He lavished such bounty on him?” Despite criticism, even from family members, Rockefeller donated enormous sums to many causes, especially medical research (in the form of Rockefeller University) and higher education. He financed the founding of the University of Chicago as an institution that would train students to pursue their professional and business interests under the guidance of Christian faith.

Still, as Ida Tarbell pointed out in her work, Rockefeller’s business ethics were not above reproach. In making his fortune, he pursued markedly Darwinian practices revealing a conviction in survival of the fittest. Later in life, and as his philanthropic motivation increased, his endowment of several charitable causes more fully reflected his belief as to how God wished him to dispose of a sizable portion of his wealth.

Link to Learning

Of course, Rockefeller’s concept of stewardship—an attitude toward money and capital that stresses care and responsibility rather than pure utility—can be found across cultures and religions in various forms, and there are many similarities among the Judaic, Islamic, and Christian views of money and its use toward a greater end. All three of these religions teach that no harm should be done to others, nor should people be treated as means toward a material end like wealth. Yet what role does a religious concept of stewardship play in the ethics of the twenty-first century? The Enlightenment attempted to separate religion and ethics but could not. Are the two concepts inextricably linked? Might the business leaders of today succeed where the Enlightenment failed?

Although religious practices and cultural assumptions remain strongly in place, fewer people in the West today profess a religion than in the past. Does this development affect the way you approach business relationships and conduct negotiations? Might we see a universal, secular code of ethics developing in place of religion? If so, how would it accommodate the differences across time, regions, and cultures discussed in this chapter? The Universal Declaration of Human Rights, adopted by the United Nations General Assembly in December 1948, contains a list of basic human rights such as the right to life, liberty, due process, religion, education, marriage, and property. Business ethics will have to balance all these factors when adopting standards of conduct and local practices.

What Would You Do?

Jillian Armstrong leads an external audit team reviewing the financial statements of Islamabad Investment Bank in Islamabad, Pakistan. It is Ramadan, and the employees on her team are Muslims who fast each day for a month. Jillian has never fasted and believes the practice can be harmful over prolonged periods, especially in the heat of summer. She proposes several times that team members keep up their strength by drinking water or tea, but her suggestions are met with awkward silence. She has decided to leave well enough alone as long as everyone does their work, but now she faces a dilemma. What should she do for lunch? Should she eat in her office, out of sight of the team and bank employees? Have lunch in one of the local restaurants that cater to Westerners? Or perhaps fast with her team and eat at sundown?

Critical Thinking

- What do you think would be the effect of Jillian’s accepting the local custom but continuing her own personal preference at mealtimes?

- Can two ways of life exist side by side at work? Why or why not?

Business is primarily about relationships—with employees, business partners, and customers and clients. Ethical standards and practices governing these relationships depend on the environment they exist in, an environment that, in turn, depends on additional factors such as geography and religion. Religion’s role in business is less certain today; we are perhaps more likely to see a universal, secular code of ethics develop than to see religion serve as common ground for different cultures to come together.

- localization

- the process of adapting a product for non-native environments and languages, especially in other nations and cultures

Are the Values Central to Business Ethics Universal?

Learning Objectives

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Explain the difference between relative and absolute ethical values

- Discuss the degree to which compliance is linked with organizational responsibility and personal values

- Identify the criteria for a system of normative business ethics

- Evaluate the humanistic business model

One of the perennial themes in business ethics—indeed, in ethics in general—is the difference between relative and absolute values. Is it possible to identify a set of universal values that is consistent across cultures and time? We might begin with always honoring the terms of a contract, consistently treating customers and partners with honesty, and never cheating. Where could we go from there? No matter our culture, geography, or time, could we identify some basic normative behaviors to govern business conduct in general?

Absolute Values versus Relative Values

To put this question another way, is there a set of universal values that all can endorse? Are there “human values” that apply everywhere despite differences in time, place, and culture? If not, and if ethical standards are relative, are they worth having? Again, the UN Universal Declaration of Human Rights is a useful starting point for the way business can conduct itself. Let us look at how it is possible to align business with human rights in such a way that both profitability and responsibility are honored across the globe.

According to the Union Internationale des Avocats, an international, nongovernmental association of legal professionals, corruption “corrodes the democratic principles of accountability, equality, and transparency. It poses an extremely high cost to the citizenry, it saps the credibility of government and it places companies under an unbearable economic burden.” The UN Convention Against Corruption has called corruption “an insidious plague” that exists everywhere and “hurts the poor disproportionately by diverting funds intended for development, undermining a Government’s ability to provide basic services, feeding inequality and injustice and discouraging foreign aid and investment.” Corruption appears to exist everywhere, so it would seem to require a persistent and consistent answer everywhere. Can business ethics provide one?

Business ethics exists on three levels: the individual, the organizational, and the societal. At the organizational and societal levels, laws, regulations, and oversight can go a long way toward curtailing illegal activity. Business ethics motivates managers to (1) meet legal and industry governing and reporting requirements and (2) shape corporate culture so that corrupt practices such as bribery, embezzlement, and fraud have no place in the organization. In the ideal case, the organization’s culture never allows the latter, because scandals not only damage reputations but they make companies and countries much less attractive to investors. Corruption is expensive: According to the World Economic Forum, no less than $2 trillion is lost each year worldwide as a result of corruption, a staggering waste not just of resources but of credibility for business in general.

At the individual level, when corruption takes place, it is a matter of conscience. Corruption can be defeated only by individuals acting in accordance with their conscience and being supported by systems and corporate culture that encourage such action. Transparency, whistleblower programs, ethics training, and modeling of appropriate behavior by upper management can create the conditions for employees to act ethically, but conscience is a personal phenomenon. So, although the work of national, regional, and international organizations can limit corruption through enforcement and the prosecution of cases (as was the case with the revelation of the so-called Panama Papers), corruption will not be reduced in any significant way unless efforts have been made to form individual conscience and teach practical ways to act on it.

Link to Learning

Although ethical practice has been directly influenced by religion, as noted, ethics is not religion and religious belief is not a prerequisite for a commitment to business ethics. For example, although what constitutes ethical behavior in Islamic society is strongly linked to religious values, secular philosophers can endorse a highly developed commitment to commercial ethics, too. Furthermore, most religions have high ethical standards but do not address many of the problems faced in business. And although a good system of law incorporates ethical standards, the law can and sometimes does deviate from what is ethical. Finally, in the same vein, ethics is not science. The social and natural sciences provide data to make better ethical choices, but science cannot tell people what they ought to do (nor should it).

Absolute values do exist. Abstaining from cheating customers, defrauding clients, lying, and murder are fairly objective ethical values; the reason for making any exceptions must be carefully laid out. Ethical systems, whether utilitarian, rights based, or based on natural law and virtue ethics, are attempts to translate absolute values like these into workable solutions for people. From these systems has emerged a basic set of ethical norms for the business world.

Business Ethics and Compliance

A hallmark of any profession is the existence of ethical guidelines, often based on values like honesty, integrity, and objectivity. Organizational responsibility is fairly straightforward: Comply with applicable local, state, national, and international regulations. Compliance can be an immense task for industries like aerospace, pharmaceuticals, banking, and food production, due to the large number of employees involved, the certification of them that sometimes is necessary, and the requisite record keeping. Still, legal requirements are usually clear, as are the ways an organization can exceed them (as do, for example, companies such as Whole Foods, Zappos, and Starbucks). Personal responsibility is a different matter. It is either less clear what to do or harder to do it because of constant pressure to increase the organization’s profitability and the perception that “everybody else is doing it.” In the United States, companies spend more than $70 billion annually on ethics training; worldwide, the figure is more than double that.

Unfortunately, in the United States, much of this money is spent on merely meeting the minimum requirements of compliance, so that if there is ever a problem with the Department of Justice or the Securities and Exchange Commission, the organization is insulated from criticism or liability because its employees have engaged in the recommended training. Federal Sentencing Guidelines for felonies and serious misdemeanors now carry mandatory prison time for individual executives who are convicted. These guidelines also are designed to help organizations with compliance and reporting, and they introduce seven steps toward that end: (1) create a Code of Ethics, (2) introduce high-level oversight, (3) place ethical people in positions of authority, (4) communicate ethics standards, (5) facilitate employee reporting of misconduct, (6) react and respond to instances of misconduct, and (7) take preventive steps.

Many organizations focus on the letter of the law so that they can claim “good faith” in their effort to create an ethical environment. However, middle managers and employees often complain their ethics training consists of passing a computerized sexual harassment or fraud program once a year but that nothing is done to address issues in a substantive way or to change the culture of the organization, even those that have experienced problems. The focus still seems to be on organizational responsibility and compliance as opposed to individual responsibility and the formation of ethical conscience. We might argue that it is not the business of business to form people in their conscience, but the result of not doing so has become expensive for everyone concerned.

The damage done to an organization’s or government’s reputation due to scandal can be enormous and long lasting. The 2017 conviction for bribery and embezzlement of Lee Jae-yong, heir to the Samsung electronics empire, was part of a widespread corruption scandal that brought down the president of South Korea. Bribery was also at the heart of the FIFA (Fédération Internationale de Football Association) corruption scandal, in which soccer officials, marketing executives, and broadcasters were accused of racketeering, wire fraud, and money laundering by the U.S. Department of Justice in 2015. The Volkswagen emissions scandal also began in 2015, when the Environmental Protection Agency cited the German automaker for violating the Clean Air Act by cheating on emissions tests. To date, the fallout has cost the company nearly $30 billion in fines.

As the LIBOR (London Interbank Offered Rate) scandal, in which banks were manipulating rates to profit from trades, showed, ethical breakdowns often occur because systems fail or people make bad decisions, and sometimes both. In the case of LIBOR, the United Kingdom’s Serious Fraud Office determined there were inadequate systems of oversight in the setting of rates and that individual executives encouraged rate fixing, which led to the conviction of several traders, at least one of whom still maintains his innocence. The result was a staggering $6 billion cumulative fine for the banks involved (i.e., Barclay’s, J.P. Morgan Chase, Citicorp, Royal Bank of Scotland, and Deutsche Bank).

Link to Learning

If there is anything to be learned from these scandals, it is that organizations will succumb to ethics crises if they do not pay attention to their organizational culture and foster their employees’ growth as moral beings. This is even more important in industries like banking that are more susceptible to unethical behavior because of the great sums of money that change hands. Compliance is important, but business managers must attempt to go above and beyond to clearly model and enforce the highest standards of ethical behavior.

Normative Business Ethics

Normative business ethics should address systemic issues such as oversight and transparency as well as the character of individuals who make up the organization. Human flourishing may not be the immediate concern of business, but managers and employees have a significant impact on business performance. Giving employees common-sense advice and training in practical ways to counter unethical behavior, as well as ethical role models at the top of the organization, can be more effective than prevention. There are programs that do this, such as “Giving Voice to Values” at the Darden School of Business at the University of Virginia.

These programs are effective for their ability to help individuals act on their principles. As effective as they may be, however, they beg the larger question not of how someone can act on what their conscience tells them but how to determine what their conscience is telling them in the first place.

One model of ethical behavior, sometimes called the humanistic business model, may provide the answer for businesses that wish to achieve the dual goal of human flourishing and responsible profits. In this model, organizations focus on employees as a vital part of the operation and support them in their professional training, health care, education, family responsibilities, and even spiritual concerns. Leaders create positive relationships with stakeholders, including their employees, to cultivate investor goodwill and because they believe in the underlying values of trust and authenticity. The influence of positive psychology is evident, and there is much to commend in this kinder approach to the job of management that makes an effort to establish “sustainable human welfare.” However, happy employees are one thing; the human flourishing identified by Aristotle and John Stuart Mill is quite another. What, then, is missing from humanistic business?

The problem is that if anything flourishes in this model, it is often the business rather than the employees. After all, free enterprise has the interests of the enterprise at heart. But employees are human beings first, which means any attempt to improve their welfare must begin by thinking of them as human beings rather than as employees. How can businesses do this?

One alternative is to put the humanities into business. Businesses currently rely heavily on data analytics, algorithms, and statistical analyses to drive decision-making. The use of these tools is often backed by social science research in consumer behavior, behavioral finance, and cognitive studies. But looking to the humanities to understand business is an opportunity to engage business in subjects and ideas that have a tremendous, if often overlooked, impact on people. After all, literature that has stood the test of time can provide tremendous insight into human behavior, and Homer or Shakespeare may be more relevant to contemporary executive leadership than a business seminar on how to motivate employees.

In fact, we could argue that anything that makes an impact on people should legitimately be within the scope of business. Richard DeGeorge (1933–) of the University of Kansas describes what adding the humanities to business education entails:

“Students do not need psychosociological jargon in their business interactions. They do need to understand people and their motives, to know how to read and judge character, and to have the ability to imagine themselves in another’s shoes, be they those of a competitor, a boss, or a subordinate. For those dedicated to the case method, novels, short stories, and plays offer an inexhaustible storehouse of riches, more detailed, subtle, and complete than most cases written up for courses.”

In DeGeorge’s humanities model, business ethics would not prepare students to do certain things, for which they likely will be trained by their employers, but to be certain persons. DeGeorge suggests that “a course in the philosophy of business would enable students to think about the foundations of business—its values, ends, purpose, and justification . . . philosophy could add a critical element to business education, an element that would keep business education always alive and prevent it from becoming an accepted, orthodox ideology.”

Finally, if normative business ethics is to recognize and, ultimately, be based on the individual, it must address another human trait: bias. Intellectual, emotional, and social biases affect all decision-making, including those of an ethical nature. Some bias is good, as in having a favorable disposition toward those who work hard in intellectually honest ways. Bias also rewards those who support and nurture the best elements of a culture, whether corporate, social, or political. But it becomes dangerous when people use it to blind themselves to the reality around them, reinforce hardened positions even in the face of contradictory evidence, and shirk their responsibility as moral beings.

An example of bias occurs when employees engage in unethical activity because it has been sanctioned by higher-ups. They abdicate personal responsibility by assigning blame elsewhere. However, no amount of rationalization of the fear of job loss, financial pressure, desire to please a supervisor, and the rest, can justify such behavior, because it diminishes moral agency, the self-awareness, freedom, and ability to make choices based on our perception of right and wrong. And such agency needs to be at the heart of business ethics. After all, we cannot make a commitment to serve customers, develop leaders, and improve life for all stakeholders unless there is freedom and moral agency, the necessary ingredients in establishing an attitude of concern, that is, respect for oneself and for others, including all appropriate stakeholders.

Ethics Across Time and Cultures

Philosopher and historian Martin Buber (1878–1965) taught that love is not a feeling but a responsibility of one person for another. Feelings may come and go, but the solidarity that people have with each other and the care they take with one another define them as human beings. Thus, love, as responsibility, depends on relationships based on good faith and concern. Business, too, is about relationships. Without a relationship of trust, there can be no exchange of goods or services upon which economies are built.

Many people question the place of love in a business setting. When seen from Buber’s perspective, however, love is not an idyllic feeling but a driving force for justice and care. This does not deny the need for profit and financial success. It simply emphasizes the other side of the twofold purpose of business (profit and responsibility). In fact, John Mackey, the founder of Whole Foods, has said that love has been the basis of his success in business, which translates into care and concern for customers beyond profit and for workers beyond productivity.

If there is anything that transcends time, place, and culture, it is love. The search for a universally applied set of ethics always comes back to it. But what does love look like in a business setting? (credit: “Love Is All You Need Signage” by Jacqueline Smith/Pexels, CC0)

Recall the statement by IBM quoted earlier in the chapter: “[IBM] remain[s] dedicated to leading the world into a more prosperous and progressive future; to creating a world that is fairer, more diverse, more tolerant, more just.”

Critical Thinking

- Can Martin Buber’s notion of love play a role in business? What would that look like?

- What responsibilities do companies have regarding justice and care? Should business ethics be grounded only on more concrete tenets? Why or why not?

Any system of business ethics must consider the processes of enculturation and acculturation as well as the fact that ethical standards may shift depending on geography or time, even if certain underlying ethical values (e.g., prohibitions against lying, fraud, or murder) may remain constant. It is usually in a business’s best interest to promote human flourishing within the organization, providing comprehensive training along a humanistic business model, which applies the social sciences to ensure profitability and responsibility in an organization as well as happy, productive employees.

- humanistic business model

- a business model for balancing profitability and responsibility fairly, especially with regard to stakeholders

- moral agency

- the self-awareness, freedom, and ability to make choices based on one’s perception of right and wrong

- universal values

- ethical principles that apply everywhere despite differences in time, geography, and culture

Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/business-ethics/pages/5-introduction