Chapter 2: Preparatory Part 2

Brian Litza, EdD, NRP

2.1 Introduction

Learning Objectives

- Identify components of communication systems.

- Describe proper radio communications between EMS providers and dispatch.

- Identify proper communication with medical direction.

- Demonstrate proper communication with receiving facilities.

- Identify attributes for increasing effectiveness and efficiency of verbal communications.

- Identify correct radio procedures for all phases of a typical call.

- Identify components of system maintenance.

- Identify considerations of phone and/or cellular communications.

Emergency Medical Services Communications

Effective communication is necessary for successful pre-hospital emergency care. From the initial 9-1-1 call to the transfer of patient care at the hospital, clear and accurate communication ensures the right resources are deployed efficiently and patient information is transmitted seamlessly. This section explores the key elements of communication in EMS, focusing on the technologies used, best practices for effective communication, and the importance of maintaining robust communication systems.

The EMS communication system is a complex network designed to facilitate the rapid and efficient flow of information between various stakeholders. Key components include:

- Base Station: A stationary radio located in a strategic position, such as a hospital, dispatch center, or a high vantage point, enabling wide-area communication coverage.

- Mobile Radios: Higher-powered two-way radios typically installed in ambulances, allowing communication with the base station and other units over a range of 10-15 miles.

- Portable Radios: Handheld radios used by EMTs and paramedics for on-scene communication when away from the ambulance, with a shorter range due to lower power output.

- Repeaters: Devices that receive transmissions from lower-powered radios and retransmit them at a higher power, extending the communication range and overcoming obstacles.

- Digital Radio Equipment: Modern systems utilize digital technology for clearer audio, increased security, and advanced features like data transmission.

- Cellular Telephones: Cell phones provide a backup communication method and enable direct communication with medical direction or receiving facilities.

![OpenAI. (2025). ChatGPT. (April 28 version) [Large language model]. https://chatgpt.com/ Infographic detailing emergency communication systems range and capabilities, as described in text](https://wtcs.pressbooks.pub/app/uploads/sites/68/2025/04/Screenshot-2025-06-26-203019.png)

Radio Communications

The primary method of communication for EMS providers continues to be radio communications. The Federal Communications Commission (FCC) assigns and licenses specific radio frequencies for use by EMS. Here’s how radio communication plays a role in the different phases of an EMS call:

- Response to the Scene:

- Acknowledge call receipt from dispatch.

- Notify dispatch when en route to the scene.

- Communicate with other responding agencies as needed (e.g., fire department, police).

- Arrival at the Scene: Inform dispatch upon arrival at the scene.

- Transport to Hospital:

- Provide updated patient information to receiving facility.

- Request further orders from medical direction if necessary.

- Leaving the Scene: Notify dispatch when departing the scene if transporting, or clearing the scene if back in service.

- Arrival at the Hospital: Inform dispatch upon arrival at the hospital.

- Leaving the Hospital: Notify dispatch when leaving the hospital to return to station.

- Arrival at the Station: Inform dispatch upon returning to the station.

Communication with Medical Direction

As an EMS provider, you operate as an extension of a physician’s license, and medical direction provides the necessary oversight and guidance to ensure you’re practicing safely and effectively. This means you need clear and concise communication for obtaining orders, clarifying procedures, and ultimately, providing the best possible care to your patients. Whether you need to administer a medication, perform a complex intervention, or simply seek advice on patient management, establishing a reliable line of communication with the online physician is essential.

When contacting medical direction, remember to be organized and concise in your transmission. Present the patient’s information in a clear and structured manner, focusing on pertinent details and avoiding unnecessary information that might distract from the clinical picture. Be accurate – provide precise and truthful information to ensure the physician has a complete and accurate understanding of the situation. This includes clearly stating the patient’s chief complaint, relevant medical history, vital signs, and your initial assessment findings. By painting an accurate picture for the physician, you enable them to provide informed and appropriate medical guidance.

Finally, always repeat orders back word for word to confirm your understanding and don’t hesitate to question any orders that seem unclear or inappropriate. This closed-loop communication helps prevent errors and ensures that you are carrying out the physician’s instructions accurately. Remember, effective communication with medical direction is a two-way street. It’s about conveying critical information clearly and concisely, actively listening to the physician’s guidance, and seeking clarification when needed. This collaborative approach ensures the delivery of safe and effective patient care in the dynamic pre-hospital environment.

Communication with Receiving Facilities

Effective communication with the receiving hospital ensures a smooth transition of care for your patient. It’s more than just letting them know you’re on the way; it’s about providing a concise and accurate overview of the patient’s condition, allowing the hospital to prepare and mobilize the necessary resources. This pre-arrival notification acts as a trigger, prompting the hospital to initiate their internal processes. By conveying key information such as the patient’s chief complaint, vital signs, and any interventions performed, you enable the hospital to select the appropriate room – be it a trauma bay, cardiac unit, or isolation room – and ensure the availability of specialized equipment like monitors, ventilators, or diagnostic tools.

Additionally, this pre-alert allows the hospital to assemble the appropriate medical team. In the case of a trauma patient, they might activate the trauma surgeon, nurses, and ancillary staff. For a cardiac patient, they might alert the cardiologist and prepare the catheterization lab. This proactive approach, driven by your communication, ensures that the right expertise is available immediately upon the patient’s arrival, minimizing delays and being able to provide potentially life-saving interventions.

A sample radio report will be something like: “This is Medic Unit 1 en route to your facility with a 60-year-old female found unresponsive with suspected stroke. Vitals are blood pressure 180 over 110, heart rate 90, respirations 12, and blood glucose of 100. ETA approximately 15 minutes.” This provides essential information to the emergency department staff. In this case, it would allow the hospital time to prepare a stroke alert, readying the CT scanner, stroke team, and potentially the neurology department. Again, effective pre-arrival communication facilitates a coordinated response, minimizing delays and optimizing patient outcomes by ensuring a seamless transition from the ambulance stretcher to definitive care within the hospital.

Effective Verbal Communication

In the world of EMS, clear and efficient verbal communication is necessary. Whether using the radio to communicate with dispatch or the hospital, or providing a verbal report to medical direction, every EMS provider must be a master of concise and accurate information exchange. This ensures patient safety, facilitates smooth coordination of care, and maintains the highest professional standards.

Radio communication requires specific etiquette to maximize clarity and efficiency. Here are some important points to using a radio for communications:

- Always make sure your radio is on, the volume is set appropriately, and the frequency is clear before transmitting.

- Be mindful of background noise and try to minimize it by shielding the microphone or moving to a quieter area.

- Use the “press to talk” (PTT) button and pause for a second before speaking to avoid clipping the beginning of your message.

- Speak clearly and slowly, using a monotone voice to minimize any misunderstanding, and maintain a consistent distance from the microphone.

- Keep your transmissions concise and avoid unnecessary words, jargon, or codes.

- Remember to protect patient privacy by refraining from using their names over the air.

- Use “affirmative” and “negative” instead of “yes” and “no.” When transmitting numbers, state the number followed by the individual digits (e.g., “13, one-three”).

- Use “we” instead of “I” when describing actions to reflect teamwork and shared responsibility.

- Avoid slander, profanity, or inappropriate language, as this can not only damage your professional reputation but could also lead to fines or lawsuits.

As a reminder, when providing a verbal report to medical direction or the receiving hospital, you need to take a structured approach. Start by identifying your unit and your level of care. Provide an accurate estimated time of arrival (ETA) and basic patient demographics like age and gender. Clearly state the patient’s chief complaint and provide a concise history of their present illness, including any relevant past medical history. Report the patient’s mental status, baseline vital signs, and pertinent physical exam findings. Describe the emergency medical care you have provided and the patient’s response to that treatment. Finally, be sure to report any changes in the patient’s condition during transport.

Beyond these specific techniques, remember to adhere to Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) regulations and never share patient names or private identifiers over the radio.

Effective communication with dispatch is equally important. Always notify dispatch when leaving the scene, arriving at the hospital, leaving the hospital, and arriving back at your station. This allows dispatch to track your unit’s status and efficiently manage resources. Upon arrival at the hospital, provide a thorough handoff report to the receiving staff. Introduce the patient, clearly state the chief complaint, describe the treatments provided and any changes in the patient’s condition en route, and share any additional findings not previously transmitted. Utilizing these communication guidelines, EMS providers can contribute to a safer, more efficient, and more professional environment for both their patients and their colleagues.

System Maintenance / Phone and Cellular Communications

To ensure that communication systems remain operational, especially during critical situations, regular maintenance is essential as well as having a backup system in case of failure. This includes periodic checks of equipment, such as radios and repeaters, by qualified technicians to identify and rectify any potential issues like frequency drift or malfunctioning components. Staying abreast of technological advancements is equally important. Upgrading to new technologies, like digital radios and cellular communication systems, can significantly enhance communication capabilities and efficiency. However, any new equipment must be thoroughly tested for reliability, range, and compatibility with existing systems before being deployed in the field.

Given the unpredictable nature of emergencies, establishing backup communication plans is crucial. This means having alternative methods in place, such as secondary radio frequencies, landlines, or even satellite phones, to ensure continuous communication in case of primary system failure. These backup systems need to be regularly tested to guarantee they are ready for immediate use when needed.

We regularly use cell phones in our day-to-day activities. We need to understand there are limitations to cellular technology. We should be aware of areas with poor signal strength, commonly known as “dead zones,” and have strategies in place to overcome these challenges. This might involve using alternative networks, switching to data modes, or relying on other communication devices like satellite phones or landline phones at designated facilities. Regular training on device operation and procedures for shifting to backup communication methods is necessary to ensure that all EMS practitioners are prepared to maintain communications during emergencies, even when primary systems fail.

By prioritizing system maintenance, embracing technological advancements, and establishing robust backup plans, EMS agencies can ensure that reliable communication remains available. This commitment to effective communication not only facilitates better patient care but also enhances the safety and efficiency of EMS operations as a whole.

Activity

If you are not familiar with radio traffic, you may listen to open channels such as in Dane County.

Broadcastify: Dane County Wisconsin Live Audio Feeds

Scroll down and choose any of the fire or EMS channels. Those with more listeners will be busier.

Other county public safety channels are available on Broadcastify.

2.2 Therapeutic Communication

Learning Objectives

- Identify principles of therapeutic communication.

- Identify strategies to develop a positive communication relationship.

- Demonstrate interview techniques that are used to obtain information from patients.

- Identify verbal defusing strategies used with a hostile patient.

- Identify the communication process and list the components of communication.

- Identify techniques to use in special interview situations.

It is important to establish a connection with the patient and foster trust during a potentially stressful and vulnerable time. This is completed by using a method called therapeutic communication. As an emergency medical responder, you can consciously influence a patient’s understanding and emotional state through skilled communication. This involves using both verbal and nonverbal techniques to encourage open expression and demonstrate empathy. By actively listening, showing genuine concern, and using appropriate language, you can create a safe space for the patient to share their feelings and concerns.

This skill relies heavily on strong interpersonal skills. It’s about connecting with the patient on a human level, building trust, and alleviating fear and anxiety. Making eye contact, for example, demonstrates that you are actively listening and engaged with the patient’s concerns. Positioning yourself at a level lower than the patient, when possible, can subtly convey respect and avoid any sense of intimidation, particularly when they are already feeling vulnerable.

Furthermore, honesty is a key factor in communication. Even when delivering difficult news, being truthful while also offering empathy and support can strengthen the patient/provider relationship. Clear and articulate speech, along with using the patient’s proper name, shows respect and personalization of care. Modulate your tone and cadence for clarity. You should also be aware of your body language to appear engaged, never bored or annoyed. Maintaining a calm demeanor, even in chaotic situations, can help de-escalate tension and display a sense of competence and control. For patients with hearing difficulties, remember to speak clearly and ensure your lips are visible, facilitating lip-reading. In essence, every interaction with a patient is an opportunity to provide holistic care that encompasses both their physical needs and emotional well-being. Through the mindful application of therapeutic communication techniques, you can effectively build a quick report with your patient and facilitate a better patient assessment which will lead to better patient care.

Effective communication in EMS is crucial for building trust and rapport with patients, which in turn leads to better patient care and outcomes. It is important to adjust your communication strategies to suit the individual needs of each patient. This includes considering their age and developmental stage, using appropriate language, and being mindful of any special needs such as hearing impairments.

Cultural sensitivity is also a concern in EMS communication. Recognize that both you and the patient bring cultural perspectives to the interaction. Avoid imposing your own cultural beliefs (cultural imposition) and be mindful of potential biases (ethnocentrism). Understand that different cultures may have varying comfort levels with eye contact, personal space, touch, and nonverbal cues. For instance, some cultures may view direct eye contact as disrespectful, while others may have different interpretations of personal space zones.

Interviewing Techniques

Effective interviewing techniques help gather information from patients. Nonverbal communication plays a significant role. Pay attention to your own physical appearance, posture, gestures, and facial expressions, as these can influence the patient’s perception of you. Similarly, be observant of the patient’s nonverbal cues, which can provide valuable insights into their emotional state and overall well-being.

Utilize a combination of open-ended and closed-ended questions to gather information. Open-ended questions encourage the patient to provide detailed responses, while closed-ended questions help elicit specific details. Ask one question at a time, allowing the patient ample time to answer. Avoid common interviewing pitfalls such as providing false reassurance, giving unsolicited advice, asking leading questions, interrupting, and using “why” questions that may make the patient feel defensive.

Verbal Diffusing Strategies

Encountering a hostile or agitated patient can be challenging. Maintaining a calm and professional demeanor helps in de-escalating the situation. Building rapport by actively listening, showing empathy, and acknowledging the patient’s concerns can help diffuse tension.

Family presence during emergencies can be a sensitive issue. EMS practitioners should be familiar with departmental policies regarding family presence and consider factors such as the patient’s age, the nature of the emergency, and the family’s preferences. Clear communication with both the patient and the family is essential to ensure everyone feels informed and supported.

Communication Process and Components

The communication process involves several key components: encoding (the sender formulating the message), the message itself, decoding (the receiver interpreting the message), the receiver, and feedback. Different types of responses can be used to facilitate effective communication:

- Facilitation: Encouraging the patient to continue speaking by using verbal and nonverbal cues like nodding and saying “Go on.” This shows the patient you’re engaged and interested in what they have to say, prompting them to elaborate.

- Silence: Allowing a pause in the conversation, giving the patient time to gather their thoughts or express emotions. This can be particularly helpful when a patient is dealing with a sensitive or difficult topic, allowing them to process their feelings.

- Reflection: Repeating or rephrasing the patient’s statements to demonstrate understanding and encourage further elaboration. This confirms that you’re actively listening and allows the patient to clarify or correct any misinterpretations.

- Empathy: Showing understanding and compassion for the patient’s situation and emotions. Statements like “This must be very difficult for you” can help build rapport and make the patient feel heard and validated.

- Clarification: Asking for more information or details about the patient’s statements to ensure accurate understanding. This is especially useful when the patient uses vague or ambiguous language, preventing misunderstandings.

- Confrontation: Pointing out discrepancies or inconsistencies in the patient’s statements or behavior. This should be done respectfully and with sensitivity, but can help address potentially important issues.

- Interpretation: Offering a possible explanation for the patient’s feelings or behaviors. This can help the patient gain insight into their situation, but it’s important to avoid making assumptions or judgments.

- Explanation: Providing factual information to the patient about their condition or treatment. This helps educate the patient and empowers them to make informed decisions about their care.

- Summarization: Briefly reviewing the key points of the conversation to ensure mutual understanding. This helps organize the information and provides closure to the interaction.

It is important to understand your responses and utilize the appropriate response based on the situation. Not all of these will be used in one encounter, but it demonstrates there are many ways to respond to a patient to assure you are hearing their words and there to help them through their emergency.

Developing Patient Rapport

While most patients are generally cooperative and willing to share information, you may occasionally encounter individuals who are unmotivated to talk. This can be due to various factors such as fear, anxiety, intoxication, or underlying medical conditions. It’s important to recognize that even when a patient seems reluctant to engage, they likely still need your help. Don’t let their initial hesitation discourage you from gathering the necessary information to provide appropriate care.

To build rapport, or supportive understanding, begin the interview as you normally would, introducing yourself and explaining your role. Use a calm, reassuring tone and maintain a non-judgmental demeanor. Start with open-ended questions to encourage the patient to express themselves in their own words, such as “Can you tell me what happened?” or “How are you feeling?” Offer positive feedback and encouragement to show you’re actively listening and that you value their input. For example, you might say, “I appreciate you sharing that with me” or “That’s helpful information.”

Ensure the patient understands your questions by using clear, concise language and avoiding medical jargon. If there’s a language barrier, utilize a language line or interpreter services if available. If the patient remains reluctant, gently persist with your questioning, rephrasing as needed and offering reassurance. Be patient, understanding, and persistent in your efforts to gather the information necessary to provide effective medical care. Remember, your ability to communicate effectively with even the most challenging patients can significantly impact their outcome.

Special Interview Situations

When communicating with elderly patients, you must be mindful of the potential for age-related sensory changes that can impact your interaction. While it’s true that aging can sometimes lead to visual and auditory deficits, it’s equally important to avoid stereotyping and to treat each patient as an individual. Don’t immediately assume an elderly patient can’t see or hear you clearly – always assess their individual needs.

If you suspect a visual deficit, take steps to optimize their ability to see you. Make sure the environment is well-lit, reduce glare if possible, and position yourself directly in front of them. If they wear glasses, ensure they have them on and are clean. Speak clearly and face the patient directly while speaking, as many individuals with hearing loss rely on lip reading. If they have a hearing aid, check that it’s in place, turned on, and has a functioning battery.

Remember, communication is a two-way street. Be patient, attentive, and observant of the patient’s responses. If they seem to be struggling to understand you, rephrase your questions or statements, and consider writing down key information. By being sensitive to the potential for sensory changes and taking proactive steps to facilitate communication, you can ensure a positive and productive interaction with your elderly patients.

Therapeutic communication is more than just talking to your patient. It is a summation of your ability to connect with your patient and obtain the necessary information to treat them effectively. There will be challenges both mentally and physically that may interfere with your communication. This can easily be overcome with the techniques discussed in this section.

Activity

View the following supplementary YouTube video on Therapeutic Communication:

2.3 Medical, Legal, and Ethical Issues in EMS

Learning Objectives

- Define appropriate emergency medical practitioner scope of practice.

- Identify the importance of Do Not Resuscitate [DNR] (advance directives) and local or state provisions regarding EMS application.

- Define consent and identify methods of obtaining consent.

- Identify the role of consent of minors in providing care.

- Identify implications for the emergency medical practitioner in patient refusal of transport.

- Define abandonment, negligence, and battery, and their implications for the emergency medical practitioner.

- Identify the importance, necessity, and legality of patient confidentiality.

- List the actions that an emergency medical practitioner should take to assist in the preservation of a crime scene.

- Identify the conditions that require an emergency medical practitioner to notify local law enforcement officials.

Emergency medical services operate at the intersection of healthcare, public safety, and the law. This section examines the legal and ethical framework which EMS providers function, highlighting key concepts such as scope of practice, consent, patient rights, confidentiality, and legal obligations.

Scope of Practice

The scope of practice for EMS professionals outlines the boundaries within which they are legally permitted to provide medical care. This scope is primarily defined by state legislation, which establishes the permissible interventions that EMS providers can perform. This legislation serves as the foundation for the provider’s actions and is further enhanced by medical direction. Medical direction, typically provided by physicians, refines the scope of practice through the implementation of protocols and standing orders. These protocols and orders offer specific guidelines for patient care, ensuring consistent and appropriate treatment. Additionally, the scope of practice often references the National Standard Curricula, which outlines the core knowledge and skills expected of EMS professionals at various levels of training.

The legal right of an EMS professional to function effectively is often contingent upon the availability of medical direction. This typically involves the ability to communicate with a physician via telephone or radio, adhere to approved standing orders and protocols, and maintain a respectful and cooperative relationship with the medical director. This collaborative relationship ensures that patient care decisions are informed and that the provider acts within the appropriate legal and medical boundaries.

Beyond the legal framework, EMS professionals are bound by ethical principles and moral obligations. These obligations emphasize the importance of prioritizing the physical and emotional needs of the patient, striving for excellence in patient care through continuous skill development and maintenance, and actively seeking opportunities for professional growth through continuing education and refresher programs. Furthermore, critical self-reflection and a commitment to improving response times, patient outcomes, and communication are essential components of ethical practice. Honesty in reporting, both internally and externally, is paramount to maintaining public trust and ensuring accountability.

Ethical dilemmas can arise in various forms within the practice of EMS. These may include situations involving the futility of care, such as attempting resuscitation in a remote location where successful resuscitation is highly unlikely. The allocation of limited resources, such as during mass casualty incidents, may necessitate difficult decisions regarding patient prioritization (triage). Additionally, ethical concerns arise in cases of professional misconduct, such as patient abuse, and instances of economic triage, such as “patient dumping,” where patients are transferred to hospitals that are ill-equipped to handle their needs.

The scope of practice for EMS professionals is a complex interplay of legal requirements, medical direction, and ethical considerations. By understanding and adhering to these guidelines, EMS providers can ensure that they provide high-quality, compassionate, and legally sound care to their patients while upholding the highest standards of professional conduct.

The fundamental duty of an EMS provider is to prioritize the well-being of their patient. This means providing compassionate and appropriate medical care within the boundaries of their training and scope of practice. Every decision and action should be guided by what is in the best interest of the patient, considering their physical and emotional needs. This includes respecting patient autonomy, providing pain relief, ensuring privacy, and offering emotional support during what can be a frightening and vulnerable experience. EMS providers must advocate for their patients, acting as their voice when they are unable to advocate for themselves. This commitment to patient well-being forms the ethical core of EMS practice.

Medical Direction

EMS providers operate as an extension of a physician medical director’s license. This means they are accountable to the medical director for the quality of care they provide. Adhering to established protocols and standing orders is crucial, as these guidelines ensure consistent and appropriate treatment modalities. Maintaining clear and open communication with medical direction is essential, especially when encountering complex cases or situations that require consultation or orders for interventions beyond the provider’s scope of practice. This collaborative relationship between EMS providers and medical direction ensures that patients receive safe and effective care that meets established medical standards.

Public Trust

EMS providers hold a position of public trust. Communities rely on them to be competent, ethical, and professional in their delivery of emergency medical services. Maintaining this trust requires a commitment to ongoing education and skills maintenance to ensure proficiency in all aspects of patient care. Professionalism encompasses not only clinical skills but also conduct, appearance, and communication. EMS providers must demonstrate respect for all individuals, maintain patient confidentiality, and act with integrity in every situation. Upholding the public’s trust is essential to the success and effectiveness of the EMS system.

Ethical Considerations

Patient Advocacy

At the heart of ethical EMS practice lies patient advocacy. This principle compels providers to prioritize the physical and emotional needs of each patient they encounter. It means recognizing that patients are often vulnerable and may be experiencing fear, anxiety, or pain. EMS providers must act as compassionate caregivers, ensuring that patient comfort and dignity are maintained throughout the entire encounter. Advocacy also involves effective communication, explaining procedures in plain language, and respecting patient wishes whenever possible. In essence, patient advocacy means placing the patient’s best interests at the forefront of every decision and action.

Competence

Maintaining a high level of competence is an ethical imperative for EMS providers. This means possessing the necessary knowledge, skills, and abilities to provide safe and effective patient care. Competence is not static; it requires a commitment to continuous improvement through ongoing training, education, and self-reflection. Staying abreast of the latest medical advancements, refining clinical skills, and participating in continuing education programs are essential for maintaining competence. By striving for excellence in their practice, EMS providers fulfill their ethical obligation to deliver the highest-quality care possible.

Honesty

Honesty and integrity are foundational ethical principles in EMS. Providers have a duty to be truthful and accurate in all aspects of their work, including patient interactions, documentation, and reporting. This includes accurately documenting assessment findings, interventions performed, and patient responses. Honesty also extends to interactions with colleagues, supervisors, and other healthcare professionals. Maintaining transparency and truthfulness fosters trust and accountability within the EMS system, ultimately contributing to better patient outcomes.

Ethical Dilemmas

EMS providers often encounter ethically challenging situations that require careful consideration and decision-making. Recognizing and addressing these ethical dilemmas is critical to providing morally sound care. Some common ethical challenges include:

- Futility of Care: Determining when continued medical intervention is no longer beneficial or desired by the patient.

- Resource Allocation: Making difficult decisions about how to allocate limited resources in mass-casualty incidents or when faced with competing needs.

- Professional Misconduct: Addressing instances of unethical behavior by colleagues or other healthcare professionals.

Navigating these ethical dilemmas requires sound judgment, adherence to ethical principles, and often consultation with medical direction or ethics committees.

By thoughtfully considering the ethical implications of their actions, EMS providers can ensure they are providing care that aligns with the highest standards of the profession.

Advance Directives

Advance directives are legal documents that empower individuals to take control of their future healthcare decisions. They provide a voice for patients when they may not be able to communicate their wishes due to illness or incapacitation. These documents offer guidance to loved ones and healthcare providers, ensuring that medical treatment aligns with the patient’s values and preferences. Here are the common types of advance directives:

Do Not Resuscitate (DNR) Orders

DNR orders are specific instructions that indicate a patient’s desire to forgo cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) or other life-sustaining measures in the event of cardiac or respiratory arrest. These orders are typically initiated by the patient in consultation with their physician and must be clearly documented and readily available to EMS providers. It is crucial for EMS providers to be well-versed in state and local regulations regarding DNR orders, as these can vary. In situations where a valid DNR order is present, EMS providers must respect the patient’s wishes and withhold resuscitative efforts. However, if there is any doubt about the validity or applicability of a DNR order, it is always best practice to initiate resuscitation and contact medical direction for further guidance.

View the Wisconsin Department of Health Services website for more information: EMS: Do Not Resuscitate Information

Power of Attorney for Health Care

A power of attorney for health care, also known as a health care proxy or medical power of attorney, allows an individual to designate a trusted person to make medical decisions on their behalf if they become unable to do so. This designated person, often a family member or close friend, becomes the patient’s advocate and decision-maker, ensuring that medical treatment aligns with the patient’s known wishes and values. This document provides a crucial safety net, ensuring that someone the patient trusts can make informed decisions during challenging medical situations.

Living Will

A living will provide more specific instructions regarding a patient’s preferences for various medical treatments. It outlines the types of life-sustaining measures the patient does or does not want, such as mechanical ventilation, artificial nutrition, or hydration. Living wills often address specific medical conditions or scenarios, guiding healthcare providers in making decisions that honor the patient’s wishes. While living wills provide valuable insight into a patient’s preferences, it’s important to remember that they may not cover every possible situation. Therefore, open communication between the patient, their health care proxy, and medical professionals is crucial to ensure that treatment decisions reflect the patient’s values and goals of care.

Consent

Informed consent is a cornerstone of ethical healthcare, respecting patient autonomy and their right to make decisions about their own medical treatment. It requires that patients be provided with clear and understandable information about the proposed treatment, including its nature, purpose, potential benefits, and possible risks. Only when a patient has this information and voluntarily agrees to the treatment can true informed consent be obtained.

- Expressed Consent: This is the most straightforward form of consent, where a competent adult patient verbally or nonverbally communicates their clear and unequivocal agreement to the proposed treatment. This might involve a patient explicitly stating “yes” or nodding their head in agreement after a thorough explanation of the procedure.

- Implied Consent: In emergency situations where a patient is unconscious, incapacitated, or otherwise unable to provide expressed consent, the law allows for implied consent. This principle operates under the assumption that a reasonable person would want to receive life-saving treatment in such circumstances. However, EMS providers should only provide care that is immediately necessary to preserve life or limb.

Consent for Minors

Obtaining consent for minors presents unique challenges. Generally, consent must be obtained from a parent or legal guardian before providing medical treatment to a minor. However, in life-threatening emergencies where a parent or guardian is unavailable, implied consent allows EMS providers to initiate necessary care. EMS providers must be familiar with state-specific regulations regarding the age of majority and exceptions, such as emancipated minors, who are legally authorized to make their own healthcare decisions.

Refusal of Treatment

Competent adult patients possess the right to decline medical care, even if that decision may have negative consequences. Before leaving the scene of a call where a patient has refused treatment or transport, the emergency medical practitioner must take several crucial steps. First, they should make a renewed effort to persuade the patient to accept standard treatment or transport to a hospital. Second, ensure the patient is capable of making a rational and informed decision. This involves assessing whether the patient is under the influence of alcohol or drugs, or if their judgment is impaired by the effects of their illness or injury. Third, the emergency medical practitioner should clearly explain to the patient the potential risks and consequences of refusing treatment or transport, emphasizing the importance of seeking professional medical care.

In situations where a patient persists in refusing treatment or transport, local protocols may dictate a consultation with medical direction for guidance. In some cases, involving law enforcement may be necessary, particularly if there are concerns about the patient’s safety or the potential for harm to themselves or others. Regardless of the circumstances, thorough and accurate documentation is essential. This includes recording all assessment findings, any medical care provided, and the patient’s refusal of standard treatment or transport. A signed refusal form by the patient further strengthens the documentation and provides legal protection for the emergency medical responders.

Key points to remember including:

- Inform the Patient: Clearly explain the potential risks and consequences of refusing treatment, including the possibility of worsening health or even death.

- Ensure Understanding: Take steps to confirm that the patient understands the information provided and is making a rational, informed decision, free from coercion or altered mental status. This can be assured by describing the information to the patient and then having them repeat back what you stated. This shows the patient received the information, processed it, understood it, and was able to reword and communicate the understanding back to you.

- Document Thoroughly: Meticulously document all assessment findings, care offered, the patient’s refusal, and any efforts made to persuade the patient to accept treatment.

- Consult Medical Direction: When in doubt, contact medical direction for guidance on how to proceed.

The decision to transport a patient ultimately rests with the patient themselves. Emergency medical practitioners should never unilaterally decide against transporting a patient, even if they believe it to be in the patient’s best interest. Respecting patient autonomy is a fundamental principle of ethical medical care. By following these procedures and maintaining meticulous documentation, emergency medical responders can ensure that they have fulfilled their duty of care while respecting the patient’s right to make informed decisions about their own healthcare.

Abandonment, Negligence, and Battery

EMS providers must be aware of the legal implications of their actions to avoid liability. Here are some key legal concepts:

- Abandonment: This occurs when an EMS provider terminates patient care without ensuring that another provider of equal or higher training assumes responsibility. This can leave the patient vulnerable and without continued care. This is focused on leaving the scene and not jumping from patient to patient as you would at a multi-casualty incident.

- Negligence: In the context of EMS, this refers to a breach of the provider’s duty to deliver a reasonable standard of care, resulting in further harm to the patient. It’s not about making a simple mistake or having a bad outcome; it’s about failing to act as a competent and prudent EMS provider would in a similar situation. To establish negligence, four key elements must be proven:

- Duty to Act: This element establishes that the EMS provider had a legal obligation to provide care to the patient. This duty can arise from various sources, such as a direct call for assistance, an existing contractual agreement with a municipality, or simply beginning treatment on a patient. Once an EMS provider responds to a call or initiates care, a duty to act is established.

- Breach of Duty: This element demonstrates that the EMS provider failed to fulfill their duty to act in a competent and reasonable manner. This could involve providing inappropriate care, failing to provide necessary care, or acting in a way that deviates from accepted EMS protocols and standards. Essentially, it means the provider did something they shouldn’t have done or didn’t do something they should have done.

- Injury to the Patient: This element establishes that the patient suffered actual harm as a result of the EMS provider’s breach of duty. This harm can be physical, such as a worsened injury or a new medical complication, or it can be emotional or psychological.

- Proximate Cause: This element links the EMS provider’s breach of duty directly to the patient’s injury. It must be demonstrated that the provider’s actions or inactions were a direct and foreseeable cause of the harm the patient suffered. In other words, the patient’s injury wouldn’t have occurred if not for the provider’s negligence.

Proving negligence in EMS requires a thorough investigation and often involves expert testimony to establish the accepted standard of care and demonstrate how the provider’s actions deviated from that standard. It’s a complex legal concept with serious implications for both patients and EMS providers.

- Battery: Battery is the unlawful touching of a person without their consent. In the EMS context, this could involve providing treatment to a competent adult who has refused care.

- Assault: For comparison, assault is the threat or attempt to inflict physical harm, which can occur without any actual physical contact. For instance, raising a fist in a threatening manner can constitute assault if it causes the victim to fear an impending strike.

By understanding these legal concepts and adhering to ethical principles and the standard of care, EMS providers can minimize their risk of liability and provide safe and appropriate patient care.

Confidentiality

Confidential information in EMS encompasses various aspects of patient care. This includes sensitive details gathered during patient interviews, such as medical history, as well as vital assessment findings and the treatments administered.

Releasing confidential patient information generally requires a written release form signed by the patient. Unauthorized disclosure, whether verbal or written, is strictly prohibited unless legal guardianship has been established. However, there are exceptions where disclosure is permissible without a patient’s written consent. These include situations where other healthcare providers need the information for continued patient care; when state law mandates reporting of incidents like rape, abuse, or gunshot wounds; for the purpose of third-party payment billing; or in response to a legal subpoena.

The Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) Privacy Rule is a cornerstone of patient privacy protection within the healthcare system. It establishes guidelines for how healthcare providers must handle and disclose patient data. Specifically for ambulance service providers, HIPAA mandates patient notification of their privacy rights, obtaining prior written permission from patients for any information disclosure, and requiring staff training on HIPAA regulations.

HIPAA outlines permissible disclosures of protected health information, such as for treatment, payment, and certain health care operations within the healthcare system. However, the Privacy Rule also includes exceptions. These include disclosures mandated by law; public health reporting; reports of abuse, neglect, or domestic violence; Workers Compensation claims; organ donation or transplantation activities; and disclosures to coroners or medical examiners. Violations of HIPAA regulations can have serious consequences, including both civil and criminal penalties.

The use of social media platforms, such as Facebook, Twitter, texting, blogging, and others, presents unique challenges to maintaining patient confidentiality. Sharing any patient information, even seemingly innocuous details, on social media platforms is strictly prohibited and can have severe repercussions for both the individual and the EMS agency.

Maintaining patient confidentiality is a moral and legal responsibility in EMS. Adhering to strict protocols and a strong ethical framework ensures patient trust and protects sensitive information.

Crime Scene Preservation

When responding to incidents that may involve a crime, EMS providers face the dual responsibility of providing patient care while also taking steps to preserve potential evidence. While patient care remains the paramount concern, providers should:

- Avoid Disturbing Evidence: Unless necessary for patient care, avoid moving or disturbing any items at the scene. If it’s necessary to move something, carefully document its original location and any alterations made.

- Observe and Document: Pay close attention to the scene and document any unusual findings or alterations that may be relevant to the investigation. This might include noting the position of the patient, the presence of weapons or other objects, and any signs of a struggle.

- Preserve Evidence: Whenever possible, avoid cutting through clothing that may contain evidence, such as bullet holes or stab wounds. If it’s necessary to remove clothing for patient care, handle it carefully and preserve it for law enforcement.

Mandatory Reporting

As discussed in the previous chapter, EMS providers serve as mandated reporters, meaning they are legally obligated to report certain situations to the appropriate authorities. These reporting requirements are designed to protect vulnerable individuals and safeguard public health. Specifically, EMS providers are required to report any suspicion of abuse or neglect, including child abuse, elder abuse, and domestic violence. Recognizing the signs and symptoms of abuse and reporting these concerns to the appropriate agencies is important to preventing further harm and ensuring victims receive appropriate support and intervention.

Additionally, EMS providers must report crimes such as gunshot wounds, stabbings, and sexual assault. This reporting requirement assists law enforcement in their investigations and helps to ensure public safety. Certain communicable diseases and animal bites are also subject to mandatory reporting. By notifying public health authorities of these incidents, appropriate measures can be taken to control the spread of disease and protect the community. Failure to comply with these mandatory reporting requirements can result in legal consequences for the EMS provider.

2.4 Lifting and Moving

Learning Objectives

- Define body mechanics.

- Identify guidelines and safety precautions that need to be followed when lifting a patient.

- Demonstrate the safe lifting of cots and stretchers.

- Identify guidelines and safety precautions for carrying patients and/or equipment.

- Identify one-handed carrying techniques.

- Demonstrate correct and safe carrying procedures on stairs.

- Identify guidelines for reaching and their applications.

- Demonstrate correct reaching for log rolls.

- Identify guidelines for pushing and pulling.

- Identify general considerations of moving patients.

- Identify three situations that may require the use of an emergency or urgent move.

- Identify the following patient-carrying devices:

- Wheeled ambulance stretcher

- Portable ambulance stretcher

- Stair chair

- Scoop stretcher

- Long spine board

- Basket stretcher

- Flexible stretcher

- Bariatric stretcher

- Powered stretcher

- Neonatal isolette

- Demonstrate with a partner how to prepare each of the following devices for use, transfer a patient to the device, properly position the patient on the device, move the device to the ambulance, and load the patient into the ambulance:

- Wheeled ambulance stretcher

- Portable ambulance stretcher

- Stair chair

- Scoop stretcher

- Long spine board

- Basket stretcher

- Flexible stretcher

- Powered stretcher

- Demonstrate with a partner the techniques for transferring a patient from an ambulance stretcher to a hospital stretcher.

Patient Moving and Lifting

Moving and lifting patients is an everyday task in EMS. Whether extricating a patient from a vehicle, carrying them down stairs, or simply transferring them to a stretcher, proper techniques are essential to ensure both patient and provider safety. This section explores the principles of body mechanics, safe lifting and carrying techniques, and the various equipment used in patient movement.

Body Mechanics

Body mechanics refers to the proper use of the body to prevent injury and facilitate efficient movement. Understanding and applying correct body mechanics is important for EMS providers who frequently lift, carry, and move patients, often in challenging environments.

Use Your Legs:

Imagine your legs as powerful pillars supporting a sturdy temple – your back. When lifting a patient or heavy equipment, always rely on the strength of your leg muscles to do the work. Keep your back straight, like a rigid column, and bend at the hips and knees, lowering your body as if you were squatting. This allows you to engage the large muscles in your thighs and buttocks, which are far better equipped for lifting than the smaller muscles in your back. By avoiding bending at the waist, you protect your spine from excessive strain and reduce the risk of injury.

Stay Close:

Picture a weightlifter hoisting a heavy barbell. They keep the weight as close to their body as possible to maintain balance and maximize lifting power. The same principle applies to patient-handling in EMS. Whether you’re lifting a patient onto a stretcher or carrying equipment, keep the weight as close to your center of gravity as you can. This reduces the leverage on your spine, minimizing strain and making it easier to maintain control.

Maintain Proper Posture:

Maintaining proper posture is crucial for preventing injuries during carrying. Keep your back straight, like a rigid column, and avoid twisting your torso. When you need to bend, do so at the hips and knees, not at the waist. This engages your leg muscles, which are designed for lifting and carrying, and protects your back from unnecessary strain. Remember to keep your core muscles engaged to provide additional support for your spine.

Avoid Bending:

Bending at the waist while lifting or lowering a stretcher puts tremendous strain on your lower back. Instead, maintain a straight back and use your leg muscles to do the work. Remember, your legs are designed for lifting, while your back is designed for support.

Kneel for Lower Objects:

If you need to push or pull an object that is below waist level, kneeling down can help you maintain a safe back position. This prevents you from bending at the waist and straining your lower back. Imagine a gardener weeding a flower bed. They kneel to keep their back straight and avoid unnecessary strain. Similarly, when retrieving equipment from a low shelf or moving a patient on the floor, kneeling allows you to maintain proper body mechanics and protect your back.

Avoid Twisting:

Think of your spine as a delicate stack of blocks. Twisting while lifting can disrupt this alignment, potentially leading to injury. Instead of twisting your torso, pivot your feet to turn your entire body. This keeps your spine in a neutral position and distributes the weight evenly, reducing the risk of strains or sprains.

Proper Foot Position:

Imagine a martial artist in a ready stance, feet shoulder-width apart, one slightly ahead of the other. This balanced and stable position provides a strong foundation for movement and power. Similarly, when lifting in EMS, maintain a solid base by keeping your feet shoulder-width apart, with one foot slightly in front for stability. This helps distribute your weight evenly and prevents you from losing your balance during the lift.

Communication:

Lifting and moving patients often requires teamwork. Clear and frequent communication with your partner is essential for coordinating movements and ensuring safety. Before lifting, discuss the plan, establish who will give the commands, and agree on cues for lifting and lowering. During the lift, maintain verbal communication, alerting your partner to any changes in weight distribution or unexpected movements.1 This teamwork approach not only enhances safety but also makes the lift smoother and more efficient.

Assess the Weight:

Before lifting and carrying a patient or a piece of heavy equipment, take a moment to assess the weight involved. Visualize the lift and consider whether you can safely handle the weight on your own or if you’ll need assistance. If you have any doubts, it’s always best to ask for help. Overestimating your abilities can lead to injuries and compromise patient safety.

Know Your Limits:

EMS providers come in all shapes and sizes, and everyone has their own physical limitations. Be honest with yourself about your capabilities and those of your team members. If someone is recovering from an injury, has a pre-existing condition, or simply isn’t comfortable lifting a particular weight, respect their limitations. Assigning tasks based on individual strengths and limitations is key to safe and efficient patient handling.

Use Enough Help:

Lifting a stretcher with a patient on it is rarely a one-person job. Ensure you have an adequate number of people to lift the stretcher safely, distributing the weight evenly. Ideally, use an even number of lifters, with one person at each corner of the stretcher. This helps maintain balance and prevents the stretcher from tilting or becoming unstable during the lift.

Push, Don’t Pull:

Imagine pushing a heavy shopping cart versus pulling it. When you push, you engage your larger leg muscles and maintain a more stable posture. The same principle applies in EMS. Whenever possible, push rather than pull heavy objects or equipment. This allows you to use your body weight and leg strength more effectively, reducing strain on your back and shoulders. Whether you’re moving a stretcher, a loaded cot, or a piece of equipment, pushing allows for greater control and reduces the risk of injury.

Push from Waist Level:

When pushing, aim to apply force from the area between your waist and shoulders. This is where your body generates the most power and stability. Think of a football player pushing against an opponent. They drive with their legs and core, applying force from their midsection. Similarly, when pushing a stretcher or other equipment, use your legs and core muscles to generate power, keeping your back straight and your movements controlled.

Power Lift:

The power lift, also known as the squat lift, is a technique that utilizes the strength of your leg muscles while protecting your back. To perform a power lift, stand with your feet shoulder-width apart, straddling the stretcher. Keep your back straight, tighten your core muscles, and squat down, bending at the hips and knees. Grasp the stretcher handles with a secure grip, and then lift by straightening your legs, keeping your back straight throughout the movement.

Power Grip:

Your grip on the stretcher handles is crucial for maintaining control and preventing accidents. Use a power grip, where your palms and fingers fully contact the handles, with all fingers bent at the same angle. This maximizes your hand strength and provides a secure hold, reducing the risk of the stretcher slipping.

Reverse Steps:

When it’s time to lower the stretcher, don’t simply drop it or bend at the waist. Reverse the steps you used to lift the stretcher. Maintain a straight back, bend at the hips and knees, and slowly lower the stretcher using your leg muscles. This controlled descent helps prevent injury and ensures a smooth transfer for the patient.

One-Handed Carrying Technique

While it’s ideal to use both hands when carrying heavy equipment, there are times when you might need to carry something with one hand. Perhaps you’re assisting a teammate, navigating a tight space, or need to keep one hand free for another task.

In these situations, maintaining proper body mechanics is necessary to avoid injury. Imagine a waiter carrying a heavy tray of food. They keep their back straight, their core engaged, and their movements controlled to prevent spilling. Similarly, when carrying equipment with one hand, keep your back in a locked-in position, avoiding any twisting or leaning to compensate for the uneven weight distribution. Engage your core muscles to provide extra support and stability. This technique helps prevent muscle strains and keeps you balanced and in control.

Carrying on Stairs

Navigating stairs with a patient can be one of the most challenging aspects of patient handling. It requires careful coordination, proper lifting techniques, and the right equipment.

- Use a Stair Chair: Whenever possible, opt for a stair chair instead of a stretcher when moving a patient on stairs. Stair chairs are specifically designed for this purpose, providing a secure and stable platform for the patient while allowing the EMS team to maintain a safe lifting posture.

- Maintain Proper Posture: Whether using a stair chair or a stretcher, maintaining proper posture is essential. Keep your back straight and avoid bending at the waist. Instead, bend at the hips and knees, using your leg muscles to lift and lower the patient. Keep the weight close to your body to minimize strain on your back and improve balance. If using a stretcher, ensure you have enough people to lift and carry it safely, with one person at each corner to maintain stability. Communicate clearly with your team, coordinating your movements to ensure a smooth and controlled descent or ascent.

Reaching

Reaching may seem like a simple action, but in EMS, even seemingly mundane movements can lead to injury if not performed correctly. Whether reaching for equipment in the ambulance, retrieving a dropped item, or assisting a patient, proper body mechanics are essential.

- Maintain Proper Posture: Imagine a dancer with perfect posture, their back straight, their core engaged. This alignment is crucial when reaching. Keep your back in a locked-in position, avoiding any twisting or bending at the waist. This protects your spine and reduces the risk of strains.

- Avoid Overreaching: Picture a gardener reaching for a weed just beyond their grasp. Overextending can strain their back muscles. Similarly, in EMS, avoid reaching too far in front of your body. If an object is more than 15-20 inches away, reposition yourself closer to it rather than straining to reach. This simple adjustment can prevent unnecessary stress on your back and shoulders.

- Limit Prolonged Reaching: Think of a mechanic working under a car, their arms extended overhead for an extended period. This sustained posture can lead to fatigue and muscle strain. In EMS, avoid situations that require prolonged or strenuous reaching. If you need to reach for something overhead, take breaks to avoid overexertion. If possible, use a step stool or ladder to bring yourself closer to the object and reduce the strain.

Reaching for Log Rolls

Log rolling is a technique used to move a patient with a suspected spinal injury, keeping their spine aligned to prevent further harm. It requires careful coordination and proper body mechanics to protect both the patient and the EMS providers.

- Maintain a Straight Back: When leaning over the patient during a log roll, keep your back straight as an arrow. Avoid hunching or rounding your back, as this can lead to strain.

- Lean from the Hips: Instead of bending at the waist, hinge at your hips, like a diver preparing to jump. This allows you to lean forward while maintaining a neutral spine position.

- Engage Your Shoulders: Use your shoulder muscles to help with the rolling motion. This distributes the workload and reduces strain on your back. Think of rowing a boat, using your shoulders and back muscles in a coordinated effort.

By following these guidelines, you can perform log rolls effectively while minimizing the risk of injury to yourself and the patient.

Emergency Moves

Picture this: you arrive on scene to find a patient trapped in a vehicle that’s leaking gasoline and emitting smoke. Every second counts. In such situations, where immediate danger threatens the patient’s life, emergency moves are necessary. These moves prioritize speed, getting the patient away from the hazard as quickly as possible. However, even in the chaos of an emergency, spinal protection remains a critical consideration.

Whenever possible, pull the patient in the direction of the long axis of their body – that is, along the line of their spine. This helps minimize spinal movement and reduces the risk of further injury. Imagine pulling a person lengthwise out of a burning car, keeping their body aligned as much as possible. This may involve dragging them by their clothing or using a blanket to pull them to safety. While emergency moves might not allow for full spinal immobilization, prioritizing axial alignment helps protect the patient’s spine while expediting their removal from danger.

Points to Remember:

- The greatest danger in moving a patient quickly is the possibility of aggravating a spine injury.

- Every effort should be made to pull the patient in the direction of the long axis of the body.

- It is impossible to remove a patient from a vehicle or other dangerous situation quickly and at the same time provide as much protection to the spine as can be accomplished with an interim immobilization device.

- If the patient is on the floor or ground, they can be moved by:

- Pulling on the patient’s clothing in the neck and shoulder area

- Putting the patient on a blanket and dragging the blanket

- Putting the EMT’s hands under the patient’s armpits (from the back), grasping the patient’s forearms and dragging the patient

Urgent Moves

Urgent moves fall between emergency moves and non-urgent moves. These situations demand swift action, but there’s a bit more time to consider spinal precautions. Picture a patient with labored breathing or signs of shock. While their life isn’t in immediate danger, their condition could deteriorate rapidly if not addressed promptly. In these cases, a rapid extrication technique might be used, allowing for some spinal protection while expediting the move to a safer location where more definitive care can be provided. The key with urgent moves is balancing the need for speed with the importance of minimizing spinal movement.

Points to remember:

Rapid extrication of patient sitting in vehicle

- One EMR gets behind the patient and brings the cervical spine into neutral in-line position and provides manual immobilization.

- A second EMR applies the cervical immobilization device as the third EMR first places the long backboard near the door and then moves to the passenger seat.

- The second EMR supports the thorax as the third EMR frees the patient’s legs from the pedals.

- At the direction of the second EMR, they and the third EMR rotate the patient in several short, coordinated moves until the patient’s back is in the open doorway and their feet are on the passenger seat.

- Since the first EMR usually cannot support the patient’s head any longer, another available EMR or a bystander supports the patient’s head as the first EMR gets out of the vehicle and takes support of the head outside of the vehicle.

- The end of the long backboard is placed on the seat next to the patient’s buttocks. Assistants support the other end of the board as the first EMR and the second EMR lower the patient onto it.

- The second EMR and the third EMR slide the patient into the proper position on the board in short, coordinated moves.

- Several variations of the technique are possible, including assistance from bystanders. Must be accomplished without compromise to the spine.

Non-Urgent Moves

Non-urgent moves are the bread and butter of patient-handling in EMS. These are situations where there’s no immediate threat to life or limb, and the patient can be moved when ready for transportation. Imagine a patient with a sprained ankle or a minor laceration. Their condition is stable, and there’s no rush to move them. In these cases, EMS providers can take their time, using proper lifting and moving techniques to ensure both patient comfort and provider safety. Non-urgent moves allow for careful consideration of spinal precautions, proper body mechanics, and the use of appropriate equipment, such as stretchers, stair chairs, or other carrying devices.

Direct Ground Lift (No Suspected Spine Injury)

- Two or three rescuers line up on one side of the patient.

- Rescuers kneel on one knee (preferably the same for all rescuers).

- The patient’s arms are placed on their chest if possible.

- The rescuer at the head places one arm under the patient’s neck and shoulder and cradles the patient’s head. They place the patient’s other arm under the patient’s lower back.

- The second rescuer places one arm under the patient’s knees and one arm above the buttocks.

- If a third rescuer is available, they should place both arms under the waist and the other two rescuers slide their arms either up to the mid-back or down to the buttocks as appropriate.

- On signal, the rescuers lift the patient to their knees and roll the patient in toward their chests.

- On signal, the rescuers stand and move the patient to the stretcher.

- To lower the patient, the steps are reversed.

View the following supplementary YouTube video to see this performed: Direct Ground Lift

Extremity Lift (No Suspected Extremity Injuries)

- One rescuer kneels at the patient’s head and one kneels at the patient’s side by their knees.

- The rescuer at the head places one hand under each of the patient’s shoulders while the rescuer at the foot grasps the patient’s wrists.

- The rescuer at the head slips their hands under the patient’s arms and grasps the patient’s wrists.

- The rescuer at the patient’s foot slips their hands under the patient’s knees.

- Both rescuers move up to a crouching position.

- The rescuers stand up simultaneously and move with the patient to a stretcher.

View the following supplementary YouTube video to see this performed: Extremity Lift

Transfer of Supine Patient from Bed to Stretcher:

Direct Carry

- Position cot perpendicular to bed with head end of cot at foot of bed.

- Prepare cot by unbuckling straps and removing other items.

- Both rescuers stand between bed and stretcher, facing patient.

- First rescuer slides arm under patient’s neck and cups patient’s shoulder.

- Second rescuer slides hand under hip and lifts slightly.

- First rescuer slides other arm under patient’s back.

- Second rescuer places arms underneath hips and calves.

- Rescuers slide patient to edge of bed.

- Patient is lifted/curled toward the rescuers’ chests.

- Rescuers rotate and place patient gently onto cot.

View the following supplementary YouTube video to see this performed, although with three rescuers: Supine Transfer – Direct Carry

Draw Sheet Method

- Loosen bottom sheet of bed.

- Position cot next to bed.

- Prepare cot: Adjust height, lower rails, unbuckle straps.

- Reach across cot and grasp sheet firmly at patient’s head, chest, hips and knees.

- Slide patient gently onto cot.

View the following supplementary YouTubes videos to see this performed with different considerations:

Drawsheet Method (Lifting and Moving)

Draw Sheet Transfer

Patient-Carrying Devices

EMS providers have a diverse toolkit of carrying devices designed to safely and effectively move patients in various situations. Here are some of the most common:

- Wheeled Ambulance Stretcher: The workhorse of EMS, this stretcher is the most commonly used device for transporting patients. Its sturdy construction, adjustable features, and smooth-rolling wheels make it versatile for a wide range of situations.

Figure 2.2 - Portable Ambulance Stretcher: For navigating tight spaces or carrying patients over short distances, the portable stretcher offers a lighter and more compact option. It can be folded or disassembled for easy storage and transport.

- Stair Chair: Stairs can be a formidable obstacle in EMS. The stair chair provides a safe and controlled way to move patients up or down stairs. Its design allows the EMS team to maintain a proper lifting posture, minimizing strain and ensuring patient safety.

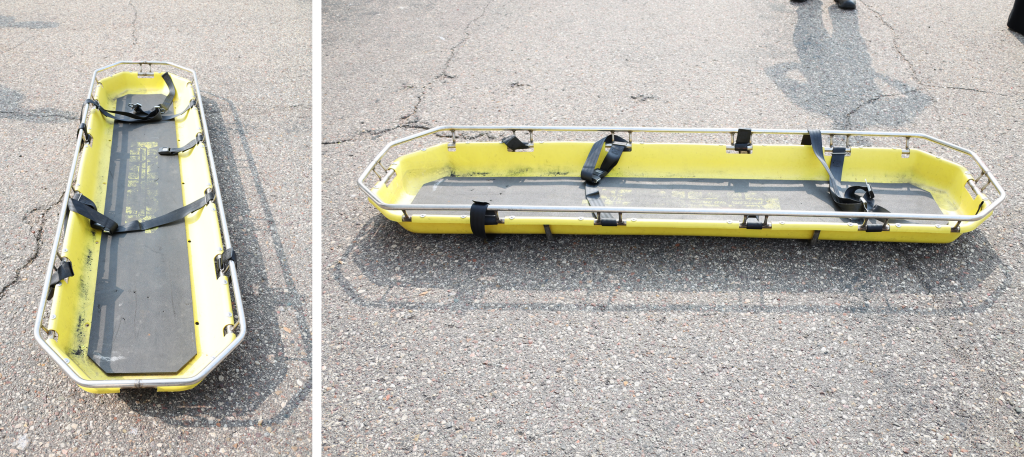

Figure 2.3 - Scoop Stretcher: This device is ideal for patients with suspected spinal injuries. It splits into two halves, allowing the patient to be “scooped” up without log rolling, minimizing spinal movement.

Figure 2.4

- Long Spine Board: Used for immobilizing and transporting patients with suspected spinal injuries, the long spine board provides a rigid platform to secure the patient and prevent further spinal movement.

Figure 2.5 - Basket Stretcher: Rugged and versatile, the basket stretcher is designed for extricating patients from rough terrain, such as wilderness areas, ravines, or industrial sites. Its sturdy construction and secure straps protect the patient during transport over uneven ground.

Figure 2.6 - Flexible Stretcher: This lightweight and adaptable stretcher conforms to the patient’s body and can be rolled up for easy storage and transport. It’s particularly useful in confined spaces or for extricating patients from challenging environments.

Figure 2.7 - Bariatric Stretcher: For obese patients, the bariatric stretcher offers increased weight capacity and wider dimensions to ensure safe and comfortable transport.

- Powered Stretcher: This innovative stretcher features a motorized lifting system that reduces the physical strain on EMS providers. It allows for effortless raising and lowering of the stretcher, making patient handling easier and safer.

- Neonatal Isolette: Specifically designed for newborns, the neonatal isolette provides a controlled environment for transporting infants, maintaining temperature, humidity, and oxygen levels.

View the following supplementary YouTube videos to see how these devices are used:

- Lifting Mechanics and How to Operate the Stretcher

- This is a different model of stretcher: Stretcher Use and Movement

- Stryker Stair Chair Tutorial

- This is a different model of stair chair: How Operate the Stairchair (EMT Skill)

Patient Positioning

Proper patient positioning on the stretcher is more than just about comfort; it’s a crucial aspect of patient care that can significantly impact their well-being and outcome. Think of it as tailoring the stretcher to the patient’s specific needs, optimizing their position to facilitate breathing, maintain circulation, and prevent complications. In patients with both airway and spinal injury considerations, the airway takes priority.

- Unresponsive Patients: For unresponsive patients without suspected spinal injuries, the recovery position is key. This side-lying position helps maintain an open airway and prevents aspiration if the patient vomits. Imagine gently rolling the patient onto their side, ensuring their head is tilted slightly downward to allow fluids to drain from their mouth. This simple maneuver can be life-saving.

- Patients with Chest Pain or Difficulty Breathing: Patients experiencing chest pain or shortness of breath often find it easier to breathe in a sitting (Fowler’s) or semi-sitting (semi-Fowler’s) position. This upright posture allows for better lung expansion and reduces the work of breathing. However, if the patient has low blood pressure, keeping them flat might be necessary to ensure adequate blood flow to the brain. Always assess the patient’s overall condition and adjust their position accordingly.

- Patients with Suspected Spinal Injuries: For these patients, spinal motion restriction is necessary. Placing the patient lying on their back (supine) on a firm surface, a long spine board, or scoop stretcher and maintaining a neutral spinal alignment helps prevent further injury. If the patient’s condition allows, slightly elevating the head of the stretcher can help reduce spinal pressure and improve breathing.

- Patients in Shock: Shock, or hypoperfusion, is a life-threatening condition characterized by inadequate blood flow to vital organs. Place the patient supine. Level of consciousness and airway must be monitored closely. Trendelenburg position (legs elevated) is no longer widely recommended and can be detrimental.

- Pregnant Patients: In pregnant patients, the weight of the developing fetus can compress major blood vessels, potentially leading to hypotension, especially when lying flat on their back. Transporting these patients on their left side helps alleviate this pressure and maintain adequate blood flow to both the mother and the fetus. If spinal precautions are needed, slightly tilt the long board to the left using padding.

- Nauseated or Vomiting Patients: For patients experiencing nausea or vomiting, prioritize airway control. Position them in a way that allows for easy access to their airway in case they vomit, such as the Fowler’s or recovery positions, and be prepared to suction if necessary. While comfort is important, ensuring the patient can breathe freely and doesn’t aspirate vomit takes precedence.

View the following YouTube video short from Master Your Medics on positioning: Patient Positioning Examples

You can also see examples of the same positions by visiting the Repositioning Clients section of Chapter 13.2 from Open RN Nursing Fundamentals.

References

American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons. (2023). Emergency care and transportation of the sick and injured (12th ed.). Jones and Bartlett.

Bell, B., & Farmer, D. (2025). Oral/interpersonal communication. WisTech Open. https://wtcs.pressbooks.pub/oralinterpersonalcomm/

Gillespie, C. B. (2013). Code of ethics for EMS practitioners. National Association of Emergency Medical Technicians. https://www.naemt.org/about-ems/code-of-ethicsf Ethics

Mangles, P. (2024). Exploring ethical dilemmas: An analysis of moral challenges in paramedic education. Journal of Emergency Medical Services [Internet]. https://www.jems.com/ems-training/analysis-of-moral-challenges-in-paramedic-education/

National Registry of Emergency Medical Technicians. (n.d.). The continued competency initiative. https://www.nremt.org/Document/Continued-Competency-Initiative

Office for Civil Rights. (2024). HIPAA for professionals. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. https://www.hhs.gov/hipaa/for-professionals/index.html