9.8 First Trimester Prenatal Care

The second prenatal visit is often the only other follow-up visit in the first trimester because the first prenatal visit is typically scheduled at eight weeks of gestation, and the second visit is scheduled before 13 weeks’ and 6 days’ gestation. Follow-up visits are less time intensive for the client than the first prenatal visit.

Interval History

The interval history is obtained, and the client is asked if they have experienced any of following symptoms since the previous prenatal visit[1]:

- Vaginal discharge, bleeding, or leaking of fluid

- Epigastric or abdominal pain

- Pelvic pressure or uterine cramping

- Back pain or dysuria

- Dizziness or syncope

- Headache

If the client responds “Yes” to any of the symptoms, the nurse communicates these changes to the health care provider who determines if additional evaluation or treatment is required.[2]

Objective Data

The client is weighed, and their blood pressure is measured. This data is compared to baseline data from the first prenatal visit. The client provides a urine specimen that is tested for glucose, protein, nitrites, blood, and ketones by urine dipstick.

The physical exam at the second prenatal visit consists of auscultating the fetal heart rate and assessing the size of the uterus. The fetal heart rate is expected to be 110 to 160 beats per minute. If the client is at 12 or more weeks of gestation, the fundus can be palpated.[3]

The health care provider discusses laboratory results from the first prenatal visit and offers additional screenings that are performed during the first and second trimesters of pregnancy.

Screenings and Diagnostic Tests

The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) recommends that all pregnant women be offered prenatal genetic assessment through screening and diagnostic tests regardless of risk factors. A screening is a test used during pregnancy to identify whether a fetus is more or less likely to have certain birth defects, many of which are genetic disorders. Genetic testing allows clients the opportunity to seek counseling for obstetric management and recommendations, early referral to pediatric subspecialists, or earlier and safer pregnancy termination if the results are abnormal. The decision to have prenatal screening is up to each pregnant woman. A positive screening indicates a higher risk of the fetus having a genetic, chromosomal, or structural abnormality, and further diagnostic testing is needed to confirm a diagnosis. Some couples choose to have prenatal testing to plan for medical care their child may need. Other couples choose to terminate the pregnancy if the results are abnormal.[4]

Integrated Screenings

Integrated screening is a series of tests performed during pregnancy to estimate the risk of a fetus having certain birth defects, such as Down syndrome, spina bifida, and trisomy 18. The test is done in two stages, with the first stage taking place between 10 and 13 weeks of pregnancy and the second stage between 15 and 22 weeks. The screenings include an ultrasound for nuchal translucency screening and a blood test called a multiple marker screen to measure the level of pregnancy-associated plasma protein A (PAPP-A) and free hCG. The ultrasound and blood work results are combined with the pregnant woman’s age to calculate the risk of the fetus having Down syndrome, trisomy 18, or other defects.[5]

Ultrasound for Nuchal Translucency Screening

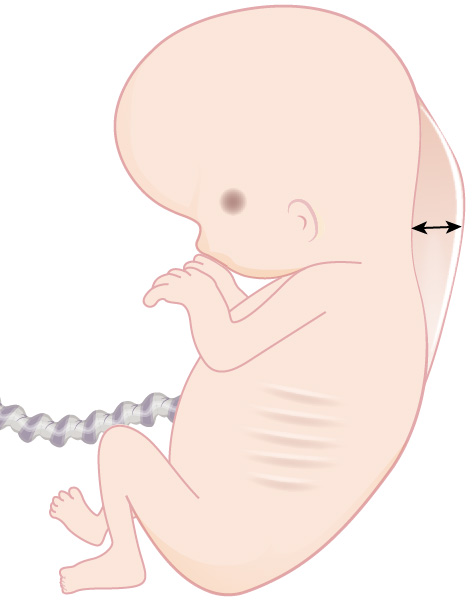

Nuchal translucency screening is an ultrasound scan that measures the thickness of space at the back of the fetus’s neck, known as the nuchal fold thickness. This screening assesses the risk of trisomy 21 (Down syndrome) and heart, abdominal wall, and skeleton defects. Nuchal translucency screening is usually done between 11 and 14 weeks of gestation. During pregnancy, it is common for fetuses to have some fluid at the back of their neck. However, if the fetus has Down syndrome or another genetic disorder, there may be an increase in the amount of fluid present, causing the space to appear thicker on an ultrasound.[6] See Figure 9.18[7] for an illustration of nuchal translucency.

Multiple Marker Screen

A multiple marker screen is a blood test that screens for chromosomal disorders and neural tube defects between 10 and 14 weeks of pregnancy using Pregnancy Associated Plasma Protein-A (PAPP-A) and free B-hCG markers. PAPP-A measures the level of a protein produced by the placenta. If PAPP-A levels are low before the 14th week, there may be an increased risk of Down syndrome and trisomy 18. Free B-hCG is a hormone produced by the placenta. High levels of hCG may indicate an increased risk of Down syndrome.[8]

Cell Free DNA (cfDNA)

A cell-free DNA (cfDNA) screening is a blood test that can be done as early as ten weeks’ gestation and up until delivery and screens for certain conditions caused by an abnormal number of chromosomes. The maternal blood sample obtained is analyzed for an abnormal amount of DNA from chromosomes 21, 18, and 13. This test screens for trisomy 21 (Down syndrome), trisomy 18 (Edwards syndrome), and trisomy 13 (Patau syndrome). This screening has a high accuracy rate compared to other prenatal screenings. If the results come back negative, it is unlikely the fetus has a chromosomal disorder. However, if the results are positive, the fetus is at risk for having a chromosomal disorder, and further testing is needed to confirm a diagnosis. Additional testing such chorionic villus sampling (CVS) or amniocentesis is performed to confirm a diagnosis. CVS is performed in the first trimester, and amniocentesis is performed in the second trimester.[9]

Chorionic Villus Sampling

Chorionic villus sampling (CVS) is a prenatal diagnostic test conducted between the 10th and 13th week of pregnancy to diagnose fetal chromosomal, metabolic, or DNA abnormalities. This test involves taking a biopsy of the placental tissue (chorionic villi) by obtaining a tissue sample from the placenta using a catheter inserted through the cervix or a needle inserted through the abdomen. Chorionic villi are microscopic projections from the outer membrane (chorion) that develop and burrow into endometrial tissue as the placenta is formed. The villi are composed of rapidly dividing cells of fetal origin that reflect the chromosomal and genetic makeup of the fetus. CVS sampling is a considered an invasive procedure that increases a client’s risk for complications such as infection or miscarriage.

Carrier Screening

Carrier screening is performed to determine if a pregnant woman or her partner carries genes for specific genetic disorders such as cystic fibrosis, hemoglobinopathies, and spinal muscular atrophy. Clients also have the option to undergo targeted or expanded carrier screening for other disorders based on their family history. A sample of blood, saliva, or cheek tissue is collected and tested. The partner with the higher likelihood of being a carrier is typically tested first. If the initial test comes back negative, no further testing is required. However, if the results indicate that the first partner is a carrier, the other partner will also undergo testing.[10]

Carrier screening is usually looking for recessive disorders. For a recessive disorder to be outwardly present, both parents must at least be a carrier of the disorder. If a person has the gene for a disorder but does not manifest symptoms of the disorder, they are a carrier. Because a carrier does not have the disorder, they often do not know that they are a carrier. When both parents carry the gene for a disorder, their child has a 25 percent chance of inheriting the gene from each of them and developing the disorder. Additionally, the child has a 50 percent chance of being a carrier of the disorder. However, if only one parent is a carrier, the child has a 50 percent chance of also being a carrier of the disorder but will not develop the disorder. If the pregnant woman and her partner are both carriers of a genetic disorder, diagnostic testing can be done on the fetus with each pregnancy to determine if the fetus has the disorder.[11]

Health Teaching During the First Trimester

Health teaching during the first trimester continues to reinforce topics introduced at the first prenatal visit, such as fetal growth and development, nutrition, common discomforts of pregnancy, and signs of complications. At 12 weeks of pregnancy, the fetus is still vulnerable to teratogens, and the nurse reinforces the importance of healthy lifestyle choices. If the client is a smoker, the nurse should determine if the client has stopped or decreased cigarette smoking. When reviewing the signs of complications of pregnancy, the nurse stresses when to call the health care provider.[12]

- Giles, A., Prusinski, R., & Wallace, L. (2024). Maternal newborn nursing. OpenStax. https://openstax.org/books/maternal-newborn-nursing/pages/1-introduction ↵

- Giles, A., Prusinski, R., & Wallace, L. (2024). Maternal newborn nursing. OpenStax. https://openstax.org/books/maternal-newborn-nursing/pages/1-introduction ↵

- Giles, A., Prusinski, R., & Wallace, L. (2024). Maternal newborn nursing. OpenStax. https://openstax.org/books/maternal-newborn-nursing/pages/1-introduction ↵

- Giles, A., Prusinski, R., & Wallace, L. (2024). Maternal newborn nursing. OpenStax. https://openstax.org/books/maternal-newborn-nursing/pages/1-introduction ↵

- Giles, A., Prusinski, R., & Wallace, L. (2024). Maternal newborn nursing. OpenStax. https://openstax.org/books/maternal-newborn-nursing/pages/1-introduction ↵

- Giles, A., Prusinski, R., & Wallace, L. (2024). Maternal newborn nursing. OpenStax. https://openstax.org/books/maternal-newborn-nursing/pages/1-introduction ↵

- “96739ca7f27af80e8ea23ad32ee2fccc32d3bb04” by OpenStax is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/maternal-newborn-nursing/pages/13-1-prenatal-testing-during-the-first-trimester ↵

- Giles, A., Prusinski, R., & Wallace, L. (2024). Maternal newborn nursing. OpenStax. https://openstax.org/books/maternal-newborn-nursing/pages/1-introduction ↵

- Giles, A., Prusinski, R., & Wallace, L. (2024). Maternal newborn nursing. OpenStax. https://openstax.org/books/maternal-newborn-nursing/pages/1-introduction ↵

- Giles, A., Prusinski, R., & Wallace, L. (2024). Maternal newborn nursing. OpenStax. https://openstax.org/books/maternal-newborn-nursing/pages/1-introduction ↵

- Giles, A., Prusinski, R., & Wallace, L. (2024). Maternal newborn nursing. OpenStax. https://openstax.org/books/maternal-newborn-nursing/pages/1-introduction ↵

- Giles, A., Prusinski, R., & Wallace, L. (2024). Maternal newborn nursing. OpenStax. https://openstax.org/books/maternal-newborn-nursing/pages/1-introduction ↵

A test used during pregnancy to identify whether a fetus is more or less likely to have certain birth defects, many of which are genetic disorders.

A series of tests performed during pregnancy to estimate the risk of a fetus having certain birth defects, such as Down syndrome, spina bifida, and trisomy 18.

An ultrasound scan that measures the thickness of space at the back of the fetus’s neck, known as the nuchal fold thickness.

A blood test that screens for chromosomal disorders and neural tube defects between 10 and 14 weeks of pregnancy using Pregnancy Associated Plasma Protein-A (PAPP-A) and free B-hCG markers.

A blood test that can be done as early as ten weeks gestation and up until delivery and screens for certain conditions caused by an abnormal number of chromosomes.

A prenatal diagnostic test conducted between the 10th and 13th week of pregnancy to diagnose fetal chromosomal, metabolic, or DNA abnormalities.

Microscopic projections from the outer membrane (chorion) that develop and burrow into endometrial tissue as the placenta is formed.

A person who has the gene for a disorder but does not manifest symptoms of the disorder.