9.7 First Prenatal Visit

The initial prenatal visit starts with obtaining the client’s health history and data related to the signs and symptoms of pregnancy. The pregnancy is confirmed, and the client’s estimated date of delivery (EDD) is determined using the client’s recollection of the first day of their last menstrual period (LMP). An ultrasound may be performed to confirm the EDD. A physical exam is completed by the health care provider, and specimens for initial prenatal laboratory and diagnostic tests are obtained. The visit ends with health teaching about multiple topics for keeping healthy during the pregnancy and scheduling the next prenatal visit.

Health History

At the first prenatal visit, a comprehensive health history is obtained, including demographic data, past medical and surgical history, current medications, family health and genetic history, lifestyle and health practices, current medications, history of drug use, and exposure to sexually transmitted infections (STIs). An obstetric history, nutritional assessment, depression screening, and intimate partner violence screen are also completed during the first prenatal visit. The goal of the health history is to obtain baseline data on the client and the client’s partner (or the biological father or sperm donor of the fetus) to identify risk factors that could affect the client, fetus, and newborn.[1]

Demographic Data

The age of a pregnant woman can be a risk factor for complications, especially if the person is 19 years old or younger when conception occurred or will be 35 years old or older at the estimated date of delivery. Clients at the lower and higher ends of the age continuum are at increased risk for preeclampsia, gestational diabetes, preterm delivery, prolonged labor, and delivery by cesarean section.[2]

Where the client lives provides cues for social determinants of health, such as potential problems with access to care (i.e., lack of reliable transportation to and from prenatal visits and diagnostic testing ordered during the pregnancy), exposure to environmental toxins, and neighborhood violence. Members of the client’s household also represent the support system available to the client throughout the pregnancy and after the baby is born.[3]

Sociocultural considerations, such as the client’s race, ethnicity, religious practices, primary language, education, and occupation, often impact pregnancy. Race and ethnicity play a role in dietary intake and risk for certain genetic disorders. Religious practices may influence dietary intake and choice of prenatal care provider and place of delivery.[4]

The client’s primary language and highest level of education influence both their literacy and health literacy levels. The prenatal period is an optimal time for the nurse to screen for health literacy and for the health care provider to increase the client’s health literacy. Availability of medical interpreters and verbal and written education in the client’s primary language are essential to promote awareness of actions to maintain a healthy pregnancy and early recognition of potential problems during the prenatal period.[5]

The occupations of the client and their partner can affect the pregnancy due to exposure to stress and environmental pollutants. Stress can raise the client’s blood pressure, decrease resistance to infection, interfere with sleep, and affect dietary intake. Each of these factors also influences fetal growth and development and increases the risk for low birth weight and preterm delivery. Stress can also increase the incidence of intimate partner violence during pregnancy. Exposure to environmental pollutants and teratogens raises the risk for congenital malformations as well.

Medical and Surgical History

The client’s medical and surgical history reveals current and past medical problems that may occur again or worsen during the pregnancy. Chronic illnesses such as anemia, diabetes mellitus, hypertension, thyroid disorders, autoimmune diseases, sickle cell disease, thalassemia, cystic fibrosis, and Tay-sachs disease should be documented, as well as a history of eating disorders. Frequent urinary tract infections are an example of an intermittent medical problem that increases the risk for complications for the entire perinatal period. Surgeries and other procedures that may place the pregnancy at risk include previous uterine surgery, loop electrosurgical excision procedure (LEEP), and repair of a fractured pelvis.[6]

Current Medications and Over-the-Counter Supplements

A list of prescribed medications, over-the-counter (OTC) medications, vitamins, minerals, and dietary supplements that have been taken by the client since the first day of their last menstrual period is obtained and provides the health care provider a baseline to screen for teratogens. The embryo and fetus are especially vulnerable to teratogens in the first trimester. The client’s current medications list also provides the nurse with a foundation for healthy teaching on the safety of medications and supplements during pregnancy.[7]

Clients with preexisting medical conditions are often taking drugs prescribed by other health care providers, so it is important for them to inform their other health care providers they are pregnant to ensure medication safety. Obstetric care providers often work hand-in-hand with other health care providers, such as endocrinologists, when clients have thyroid disease or diabetes.[8]

Lifestyle and Health Practices

Other lifestyle and health practices are assessed, including if the client is currently using or has a history of using tobacco products, alcohol, opioids, marijuana, or illegal substances, especially since their LMP. These substances are linked with adverse maternal and fetal outcomes.[9]

Discussing current exercise and activity levels with the client assists in developing an exercise plan during pregnancy. Exercise is encouraged because staying active during pregnancy is associated with fewer musculoskeletal complaints, decreased risk of preeclampsia and gestational diabetes mellitus, and shorter length of labor. If a client is inactive prior to conception, exercise should be increased gradually.[10]

Obtaining a 24-hour diet recall from the client provides the data to evaluate the client’s dietary habits and nutritional status. Inadequate or poor nutritional intake is associated with low birth weight, prematurity, and preeclampsia. Low fiber and inadequate water intake increase the risk of constipation during pregnancy.[11]

The client should also be asked if they use other health practices such as massage therapy, acupressure, acupuncture, Ayurveda, homeopathy, or other home remedies. This information should be documented in the electronic health record (EHR) for discussion with the health care provider regarding the safety of the continued use of these practices.[12]

Household contact with cats should be documented and health teaching provided regarding toxoplasmosis and reducing the risks for exposure. Toxoplasmosis is a parasitic infection that can be transmitted to pregnant women through handling cat feces or exposure to insects that come in contact with cat feces, in addition to consuming undercooked meats. This infection then crosses the placental barrier to infect the fetus, which can cause several problems such as premature birth, enlarged liver, eye damage, intellectual disability, seizures, and other nervous system complications.[13]

Obstetric and Gynecologic History

During the obstetric history-taking process, the client’s estimated date of delivery is determined. Information is also obtained about any previous pregnancies to establish the client’s gravidity and parity, both of which will be defined and discussed later in this section. A gynecologic history is obtained to identify additional risk factors affecting the pregnancy.[14]

Estimated Date of Delivery

The estimated date of delivery (EDD) is the date the pregnant woman is expected to give birth, plus or minus two weeks. The “plus or minus two weeks” of the calculated EDD takes into consideration the normal variations in a menstruating person’s cycle. When the pregnant woman is confident of the first day of their last menstrual period (LMP), the EDD is determined using Naegele’s Rule. Naegele’s Rule is a three-step calculation based on a 28-day menstrual cycle used to determine a pregnant woman’s due date. Using Naegele’s Rule, the nurse first subtracts three months from the first day of their LMP and then adds seven days and then adjusts the year as indicated.[15] See a sample calculation in the following box.

Sample Naegele’s Rule Calculation

Date of LMP: April 6, 2024

Subtract 3 months: January 6, 2024

Add 7 days: January 13, 2024

Adjust the year to the following year: January 13, 2025

View a supplementary YouTube video[16] on using Naegele’s Rule calculation:

Gravidity and Parity

Gravidity and parity indicate the client’s reproductive history in numerical form. Gravidity refers to the total number of times the client has been pregnant (including the current pregnancy), regardless of the outcome or number of fetuses. Parity is the number of pregnancies where the client has given birth to a fetus that was 20 weeks of gestation or more, regardless of whether the pregnancy ended in a live birth or fetal demise. For example, a client who is pregnant for the third time and the outcome of the two previous pregnancies was a live birth at 37 weeks and a fetal demise at 28 weeks, the nurse would document G3/P2. Abortion is the medical term for a pregnancy ending at 20 weeks of gestation or less, regardless of if it was induced or a spontaneous miscarriage.[17]

Gravidity and parity can be expanded on in several ways based on the health care provider’s preference. The most common method of detailing gravidity and parity is using the G/TPAL (gravida, term, preterm, abortion, living) method[18]:

G: Gravida (or gravidity) is the number of pregnancies, including the current pregnancy.

T: Term is the number of births at 37 weeks of gestation and later.

P: Preterm is the number of births at >20 weeks of gestation and before 37 weeks.

A: Abortion is the number of pregnancies ending before 20 weeks of gestation.

L: Living is the number of children the pregnant woman has given birth to who lived past 28 days from the date of birth.

To determine a client’s gravidity and parity using G/TPAL, follow this process[19]:

- Determine how many times the client has been pregnant. This is the gravida or G.

- Determine the number of times the client has given birth at 37 weeks of gestation or later. This is the number of term, or T, births.

- Determine the number of times the client has given birth after 20 weeks of gestation but before 37 weeks. This is the number of preterm, or P, births.

- Determine the number of pregnancies that have ended before 20 weeks of gestation. This is the number of abortions or A.

- Determine the total number of living children the client has given birth to. This is the number of living or L.

Sample G/TPAL1

For example, consider a pregnant woman whose reproductive history reveals she has given birth twice. The first child was born a week early, and the second child was born four weeks early. She also miscarried twins during the fourth month of pregnancy. Here is how her G/TPAL score would be determined:

G = 4 (she is currently pregnant)

T = 1 (1 week early is 39 weeks)

P = 1 (4 weeks early is 36 weeks)

A = 1 (4 months is 16 weeks, and a multiple gestation pregnancy is considered one birth)

L = 2

This client’s G/TPAL is G4 P1112.

View a supplementary video[20] on calculating gravidity and parity:

Nurses must use caution when discussing gravida and parity with the expectant mother in the presence of others to ensure confidentiality. Although the antepartum record may indicate a previous pregnancy or childbirth, she may not have shared this information with her family, and her right to privacy could be jeopardized by probing questions in their presence.

Obstetric History

In addition to EDD and determination of gravidity and parity, other information obtained during an obstetric history may include information about previous pregnancies and deliveries, including the following:

- Length of previous gestations: Previous preterm birth increases the risk for repeated preterm birth.

- Weight of previous infants at birth: Birth of a previous infant more than 4,000 g (8.8 lb) increases the risk for cesarean birth, infant birth injury, maternal gestational diabetes, and neonatal hypoglycemia.

- Labor experiences, type of deliveries, locations of births, names of previous physicians or midwives: Previous cesarean birth can impact the choice of delivery for the current pregnancy. Previous labor experiences can impact expectations and/or anxieties regarding labor and delivery during this pregnancy.

- Types of anesthesia and any difficulties with anesthesia during childbirth or previous surgeries: Previous difficulties with anesthesia impact the type of anesthesia that may be used during labor and delivery of the current pregnancy.

- Previous maternal complications: Previous maternal complications such as hypertension, preeclampsia, eclampsia, gestational diabetes, infection, or excessive bleeding increase the risk for complications during this pregnancy.

- Rh sensitization: Rh sensitization from previous pregnancies, miscarriages, or induced abortions can pose significant risks for Rh-negative individuals carrying an Rh-positive fetus. The nurse also reviews lab data for Rh type and history of Rhogam administration.

- Previous newborn complications or fetal/neonatal death: The loss of a previous pregnancy, whether through miscarriage (loss of pregnancy after 20 weeks’ gestation) or neonatal death (death of a newborn within the first 28 days of life), can have profound emotional, psychological, and medical implications for the individual and their subsequent pregnancies.

- Methods of infant feeding used in the past and planned for this infant: Previous successes or challenges with breastfeeding can impact the decision for infant feeding after delivery.

- Mood disorders before, during, or after previous pregnancies: Mood disorders can impact maternal health behaviors during and after pregnancy, such as poor nutrition, inadequate prenatal care utilization, substance misuse, nonadherence to medical recommendations, and increased risk for postpartum depression.

- Other concerns: Other concerns lingering from previous pregnancies and deliveries should be addressed with anticipatory guidance.

Gynecologic History

The gynecologic history provides information that may place the pregnancy at risk and includes whether the pregnant woman has ever been diagnosed with a reproductive cancer, breast disorder, menstrual disorder, or sexually transmitted infection. Previous reproductive surgeries or diagnostic tests are included in the gynecologic history. Multiple terminations of pregnancy, dilatation and curettage (D&C), cervical biopsies, and other reproductive procedures weaken the cervix and place the pregnant woman at risk for cervical insufficiency and preterm delivery. Multiple terminations of pregnancy can also produce cervical scarring, leading to problems with cervical dilation during labor. Uterine anomalies can also increase the risk of preterm delivery. Previous uterine surgeries increase the risk of abnormal placement of the placenta and uterine rupture during labor, and a cesarean birth may be recommended based on the location of the placenta and type of uterine scar. Breast surgery can interfere with breastfeeding.[21]

Genetic History

The genetic history includes information on the pregnant woman, the biological father or sperm donor of the fetus, and their respective families. Any known genetic condition of the parents and their families that can be inherited by the fetus is documented. The most common genetic conditions include the following: cystic fibrosis, trisomy 21, Tay-Sachs disease, hemophilia, sickle cell disease or trait, congenital mental impairment, and congenital anomalies. Other factors that increase the risk for inherited disorders are also included in the genetic history, such as maternal and paternal age and shared ancestry (such as when the parents are first cousins).[22]

Interval History Since Last Menstrual Period

After completion of the health history and risk assessment, the focus of the first prenatal visit focuses on confirmation of the pregnancy. Typically, the client has missed one or two menstrual periods, and a home pregnancy test result was positive. To confirm the pregnancy, the nurse will obtain baseline subjective and objective data from the client.[23]

Baseline Subjective Data

The nurse asks the client a series of questions (known as the interval history). The questions are specific to the client’s current gestation and inquire about the presence of nausea, vomiting, dizziness, breast tenderness, vaginal discharge and spotting, lower backache, and uterine cramping. Nausea and vomiting, fatigue, and breast tenderness are expected symptoms in early pregnancy. Dizziness, vaginal discharge and spotting, lower backache, and uterine cramping are not expected and require further investigation.[24]

Baseline Objective Data

The baseline objective data for the first prenatal visit include the client’s height and weight, blood pressure and pulse, and urine dipstick results. The height and weight are entered into the electronic health record and are used to calculate the client’s body mass index (BMI). When the client is underweight, overweight, or obese, expectations for weight gain during pregnancy are different than for the client who has a normal BMI.[25]

The client’s blood pressure (BP) and pulse are taken to determine baseline values. The blood pressure of a pregnant woman is expected to be below 120/80 mm Hg and the pulse between 60 to 100 beats per minute. A slightly elevated BP may be attributed to anxiety or excitement about the pregnancy or may indicate a preexisting hypertensive disorder. The heart works harder to pump more blood to the growing fetus, which increases blood volume by 40–50%. This causes the heart rate to increase by 10–20 beats per minute. Tachycardia at the first prenatal visit may indicate anxiety or a preexisting cardiac condition. It is important for the nurse to ask the client if they know what their BP has been in the past when the BP obtained at the first or any prenatal visit is elevated.[26],[27]

A urine dipstick test is performed to check for protein, blood, glucose, ketones, bacteria, and nitrites in the urine. At the first prenatal visit, the presence of protein in the urine can be interpreted as contamination from vaginal discharge or an indication of preexisting renal disease. The presence of blood in the urine can be caused by vaginal bleeding or by a urinary tract infection. Glucose in the urine can be a sign of preexisting diabetes. Ketonuria occurs as a result of excessive vomiting. Bacteria and nitrites indicate the presence of a urinary tract infection. The nurse reviews the pregnant woman’s health history and answers to the intake questions when there are any unexpected results in the urine dipstick and informs the health care provider. The urine dipstick test is also performed to detect asymptomatic urinary tract infections, which, if not treated, can result in acute pyelonephritis.[28]

Confirmation of Pregnancy

A urine or blood pregnancy test is performed to confirm the probability of pregnancy, and the client may also have a pelvic ultrasound (US) to confirm a viable intrauterine pregnancy. The method of confirmation is based on the capabilities of the office or clinic where the initial prenatal visit takes place. Some private practices and many community or county clinics do not have an ultrasonographer and will refer the client to a facility with ultrasound capability.[29]

Pregnancy tests can be performed using the client’s urine or blood. The advantage to using urine is that the test can be performed at the same place as the initial prenatal visit. Both urine and serum pregnancy tests detect the human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG) hormone. The urine pregnancy test only detects the presence or absence of hCG (qualitative), whereas blood serum pregnancy tests can also detect the amount of hCG (quantitative). Quantitative serum hCG levels are also ordered if there is no gestational sac or cardiac activity detected by the pelvic ultrasound.[30]

If performed at the first prenatal visit, a pelvic ultrasound provides important objective data. It confirms an intrauterine pregnancy, rules out an ectopic pregnancy, provides data on the number of fetuses present in the uterus, and confirms the presence of fetal cardiac activity. The ultrasound also establishes an EDD by measuring the dimensions of the gestational sac or fetus during the first trimester of pregnancy.[31]

Screening for Factors Placing the Pregnancy at Risk

After the initial and interval health history is obtained, the screening process for factors placing the pregnancy at risk for perinatal complications begins at the first prenatal visit. The obstetric and gynecologic histories, along with the medical and surgical histories, are reviewed to determine preexisting risk factors affecting the maternal and fetal outcome. The demographic, sociocultural, and genetic factors that may cause increased risk for maternal and fetal complications are also reviewed. The most common risk factors during pregnancy include the following[32]:

- Maternal age <19 at conception or ≥35 at the EDD

- Obesity

- Nutritional deficiencies

- Substance misuse

- Hypertension

- Diabetes mellitus

- HIV

- STIs

- Hepatitis B and C

- Herpes simplex virus

- Cardiac disease

- Renal disease

- Epilepsy

- Psychiatric disorders

- Cervical procedures or surgeries

- Uterine anomalies

- Uterine surgery

- Obstetric complications in previous pregnancies

Examples of previous medical conditions that increase risks during pregnancy include the following:

- Diabetes mellitus: Increased risk for preeclampsia, cesarean birth, preterm birth, infant small or large for gestational age, neonatal hypoglycemia, or congenital anomalies.

- Hypothyroidism: Increased incidence of preeclampsia, placental abruption (separation of the placenta from the uterine wall before delivery that can cause life-threatening complications such as postpartum hemorrhage and fetal hypoxia), low birthweight, preterm birth, and stillbirth.

- Hyperthyroidism: Increased maternal risk for preeclampsia, thyroid storm, or postpartum hemorrhage.

- Cardiac disease: Increased maternal risk for cardiac decompensation and death and increased risk for fetal and neonatal death.

- Renal disease: Increased maternal risk for renal failure and preterm delivery and increased fetal risk for intrauterine growth restriction.

- Infections during the first trimester of pregnancy: Increased risk of spontaneous abortion or congenital anomalies (heart disease, blindness, deafness, bone lesions).

Physical Examination

The physical examination includes a comprehensive head-to-toe and a gynecologic pelvic exam performed by the health care provider. The data obtained during the physical exam provide the baseline assessment of the client’s current physical condition that is compared with future data obtained throughout the pregnancy for changes or trends.[33]

The physical examination is typically performed by the health care provider, but the nurse may assist with gathering and documenting some of the data. The nurse also informs the client about what to expect during the head-to-toe and pelvic exams to decrease anxiety and answer questions. Following the guidelines of trauma-informed care, recognition, knowledge, concern, and respect are especially important if this will be the client’s first pelvic exam or if there is any history of sexual abuse. The client will be asked to remove all clothing, including undergarments, and put on a paper or cloth gown before the physical examination begins. The presence of a support person near the head of the bed during the physical exam can increase the client’s comfort level and should be offered to the client. A staff chaperone may also be present during the pelvic exam.[34]

General Survey

The client’s overall appearance is observed, noting any signs of distress or discomfort, as well as their mental status, behavior, mobility, and nutritional and fluid statuses. The nurse engages in open, nonjudgmental communication to assess the client’s current emotional state and provide counseling or referrals as needed.

Review the components of a general survey in the “General Survey” chapter of Open RN Nursing Skills, 2e.

Vital Signs

Measure the client’s vital signs, including the following:

- Blood pressure: Blood pressure readings of 140/90 or greater can indicate preeclampsia or hypertension.

- Pulse: Normal heart rate during pregnancy is 60-100 beats per minute. Assess the apical pulse for one minute to assess for irregularities. Tachycardia may be a sign of hyperthyroidism, anxiety, or infection.[35]

- Respiratory rate: Normal respiratory rate during pregnancy is 16-24 breaths per minute. Monitor for signs of respiratory distress or hyperventilation.

- Temperature: Normal temperature during pregnancy is 36.7 C to 37.6 C. Elevated temperature can indicate infection.

Body Systems

Body systems are assessed with considerations regarding changes during pregnancy and common discomforts. The following subsections discuss pregnancy considerations by body system.

Review focused assessments of specific body systems in applicable chapters in Open RN Nursing Skills, 2e.

Neurological System

The client’s neurological status is assessed, including sensory and motor function and for signs of headache, visual disturbances, or changes in deep tendon reflexes, which may indicate complications such as preeclampsia.[36]

Skin and Mucous Membranes

The skin is inspected for lesions, rashes, or discoloration, including signs of striae gravidarum (stretch marks). Mucous membranes are assessed for signs of dehydration or pallor, a sign of anemia. The client’s mouth is assessed for lesions, gum disease, or dental caries that may impact nutritional intake or indicate preexisting medical or dental disorders. Gum disease is associated with an increased risk of preterm delivery.[37]

Musculoskeletal System

The extremities are assessed for symmetry of range of motion, strength, circulation, and edema. A client with limited use of their arms and hands may require assistive devices to care for their newborn. Normal range of motion of the legs is important during the second stage of labor when bearing down to deliver the baby vaginally. This may limit birthing options for clients with impairment in their lower limbs. The nurse should also ask the client if they have any difficulty walking to determine the current or future need for assistive devices during pregnancy. Gait and posture changes may occur with the growing uterus and cause strain to the lower back. Clarification of any history of scoliosis, back injury, or surgery is important to discover possible contraindications to epidural or spinal anesthesia during the birth process.

Cardiovascular System

The client is assessed for signs of edema, particularly in the hands, feet, and face. Signs of venous congestion most commonly occur in lower extremities. The absence of edema in the lower extremities is expected at the first prenatal visit. The presence of edema at the first prenatal visit may indicate preexisting renal or cardiac disease that requires further investigation. Varicosities (swollen, twisted veins that can appear just under the skin) may occur in the legs, vulva, or rectal area (i.e., hemorrhoids).[38]

The heart sounds are auscultated at the aortic and mitral valves, using both the bell and diaphragm of the stethoscope. Systolic flow murmurs are common after 24 weeks of gestation due to the normal increase in blood volume during pregnancy. Extra blood volume during pregnancy can exacerbate preexisting conditions such as aortic valve stenosis or mitral valve prolapse, resulting in heart failure. Early identification of abnormal heart sounds is important and requires a referral to a cardiologist for follow-up.

Respiratory System

Shortness of breath and dyspnea can occur during pregnancy due to a rise in progesterone, estrogen, and prostaglandin hormones that cause lung congestion, but auscultated breath sounds are expected to be clear. Auscultation of the side walls of the chest may be required when the client has enlarged breasts that interfere with anterior chest auscultation. Adventitious breath sounds, sudden dyspnea, or worsening dyspnea require further investigation.

Breasts

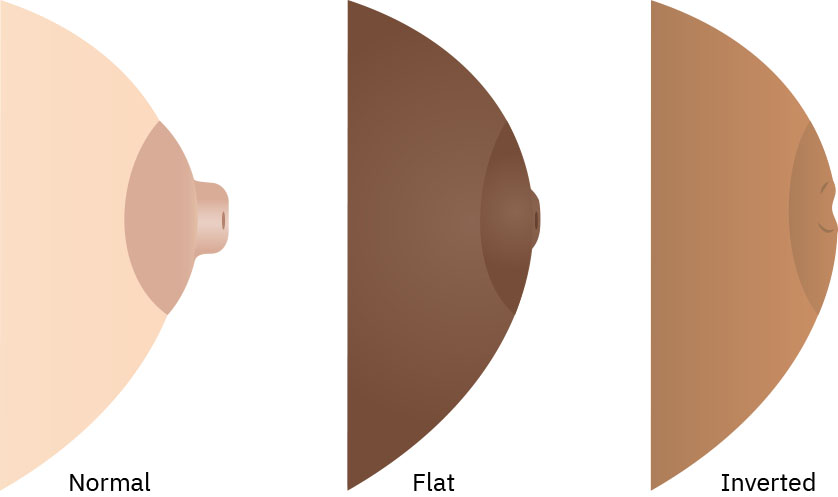

After inquiring about the presence of breast tenderness and requesting permission, the breasts are inspected for symmetry in size and shape and palpated to detect lumps or masses. The presence of colostrum is noted. The nipples are assessed because flat or inverted nipples are linked with difficulty in breastfeeding. Referral to a lactation consultant can assist the client to overcome any obstacles to successful breastfeeding caused by inverted nipples.[39] See Figure 9.16[40] for an illustration comparing normal, flat, and inverted nipples.

Abdomen

The abdominal examination starts with inspection of the skin for color, hair distribution, and scars. The contour of the abdomen is noted, and any protuberance is assessed to rule out an umbilical hernia or other abnormality. As the pregnancy progresses, the enlarged uterus will become visible, as well as linea nigra and striae gravidarum. Auscultation of bowel sounds in all four quadrants is performed before palpation. Bowel sounds may be diminished due to the effects of circulating progesterone on smooth muscle. Palpation of the abdomen is performed to determine the lower liver margin and the absence of any distention or abdominal masses. If the client is at 12 or more weeks of gestation, the fundal height is noted. The fundal height is measured from the symphysis pubis to the top of the uterus (fundus). The uterine fundus is expected to be at or right below the symphysis at 12 weeks of gestation, halfway between the symphysis and the umbilicus at 16 weeks, and at or just below the umbilicus at 20 weeks of gestation. If the client is at ten or more weeks of gestation at the first prenatal visit, fetal heart tones are auscultated via Doppler monitoring, and the fetal heart rate is counted in beats per minute. Uterine tenderness on palpation is noted, which could indicate infection.[41]

View a supplementary YouTube video[42] on an abdominal assessment during pregnancy: Pregnancy Abdomen Examination (a.k.a. Obstetric Abdominal Examination).

Pelvic Examination

The health care provider may perform a pelvic examination to obtain specimens for diagnostic testing or if there are concerns such as vaginal bleeding, pelvic pain, or suspected cervical incompetence. The pelvic exam may be deferred, especially if the client is very young or has a history of sexual trauma. The external genitalia and perineum are inspected for normal development, placement of the urinary meatus, and hair distribution. The presence of any rashes, lesions, or discharge is discussed with the client to determine if the symptom is new or ongoing. Any visible hemorrhoids are discussed. Diagnostic tests may be ordered for abnormal findings.[43]

Female Genital Mutilation

Female genital mutilation (FGM) refers to a sociocultural practice in many African, Middle East, and Asian cultures that performs partial or complete removal of female external genitalia in those assigned female at birth. Nurses caring for clients with FGM may be involved in health teaching about scheduling a cesarean birth due to FGM or the time required after a vaginal birth to repair the external genitalia.[44]

A speculum exam allows the health care provider to visualize the vaginal walls and cervix, where Chadwick’s and Goodell’s signs may be seen. A specimen for a PAP smear or HPV testing may be obtained.

A bimanual exam is performed by the health care provider by inserting two fingers of one hand into the vagina and placing the other hand just above the client’s symphysis pubis. The fingers within the vagina palpate the vaginal walls to assess for normal contour and tone, any palpable growths such as human papillomavirus (HPV) lesions, and the presence of a cystocele (prolapsed bladder into the vagina) or rectocele (rectal prolapse into the vagina). The cervical os is palpated, which is expected to be smooth, soft, and closed. If the cervical os is open, one finger is gently inserted to determine if only the external os or both the internal and external cervical os are open. The cervical length is also assessed and expected to be 4 to 5 centimeters. A cervix that is open and is shortened at less than 20 weeks of gestation is associated with an increased risk of pregnancy loss.[45]

While applying gentle suprapubic pressure with the external hand, the provider palpates the lower uterine segment for smoothness and the presence of uterine fibroids. The size of the uterus can be estimated using the distance between the external hand over the anterior uterus and the internal fingers touching the posterior uterus. When an ultrasound is not available, determining the size of the uterus manually is important to confirm the client’s current gestation and EDD. Using the anterior to posterior uterine diameter measurement fruit-equivalent method, an 8-week uterus diameter is the size of a lemon, a 12-week uterus diameter is the size of a large orange, a 16-week uterus diameter is the size of a grapefruit, and a 20-week uterus diameter is the size of a cantaloupe.[46]

The health care provider makes clinical measurements of the general shape and size of the pelvis, called clinical pelvimetry. The pelvic inlet, midplane, and outlet are assessed using the diagonal conjugate, prominence of the ischial spines, curvature of the sacrum and coccyx, width of the pubic arch, and width of the intertuberous diameter. Clinical pelvimetry at the first prenatal visit allows for identification of pelvic structure anomalies that determine an increased risk for cesarean delivery. See Figure 9.17[47] for illustrations related to clinical pelvimetry.

Common Initial Prenatal Laboratory and Diagnostic Tests

Multiple specimens are collected during the first prenatal visit for laboratory testing. These tests provide information on the presence or absence of specific STIs, immunity to or history of infections, and current status of a preexisting medical condition. The tests also determine risk for or presence of genetic abnormalities in the fetus. These tests are summarized in Table 9.7a and further discussed in the following subsections.

Table 9.7a. Common Diagnostic Tests During the Initial Prenatal Visit[48]

| Laboratory Test | Obstetric Purpose | Expected Results |

|---|---|---|

| Blood type, Rh, and antibody screen | Determine risk for ABO incompatibility and rule out Rh sensitization |

|

| Complete blood count (CBC) | Determine if infection, anemia, or thrombocytopenia are present | All values are normal |

| Rubella titer | Determine immune status | 1.0 or greater indicates immunity |

| Hepatitis B and C | Determine history of hepatitis, current infection, or chronic hepatitis infection | Negative |

| Sexually transmitted infection screening | ||

| HIV | Diagnose STI if present | Negative |

| Syphilis | Diagnose STI if present | Negative |

| Gonorrhea and chlamydia | Diagnose STI if present | Negative |

| Urinalysis | Diagnose UTI and proteinuria if present | Within normal limits (WNL) |

| Urine C&S | Diagnose UTI if present | Negative |

| Urine drug screen | Diagnose substance misuse | Negative |

| Genetic screening | ||

| Sickle cell screen | Screening for fetal risk of genetic conditions | Negative |

| Cystic fibrosis | Screening for fetal risk of genetic conditions | Negative |

| Cell-free DNA | Screening for fetal risk of genetic conditions | Negative for trisomy 21, 18, and 13 and sex chromosome abnormalities |

| Additional laboratory tests | ||

| Pap | Screen for cervical cancer | Normal cytology |

| Glucose screen (glucose challenge test, or GCT) | Screen for gestational diabetes | Less than 140 mg/dL |

| Basic metabolic panel (BMP, Chem 7, or Chem 12) | Screen for electrolyte imbalances, liver, and renal functions | Normal values |

| Thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH) | Screen for thyroid function | Normal value |

| Herpes simplex antibodies | Determine history or current infection | Negative |

Blood Type, Rh, and Antibody Screen

The client’s blood type, Rh factor, and antibody screen are obtained. If the client is Rh negative, antepartum Rho(D) immune globulin will be administered if pregnancy-related bleeding occurs at any time before labor. Rho(D) immune globulin prevents the development of Rh sensitization during pregnancy (when a pregnant woman’s immune system produces antibodies that attack the fetal red blood cells). A negative antibody screen demonstrates the client has not developed antibodies from a previous pregnancy or blood transfusion. A positive antibody screen at the first prenatal visit requires further investigation for possible interactions between the mother and the fetus that could compromise the outcome of the pregnancy.[49]

Complete Blood Count

A complete blood count (CBC) provides information on the number of white blood cells (WBCs), red blood cells (RBCs), hemoglobin, hematocrit, and platelets in the blood sample. An elevated WBC count indicates the presence of infection in the client. Decreased RBCs, hemoglobin, and hematocrit may indicate anemia, and if present, iron indices may be ordered to determine if the anemia is due to lack of iron or a different type of anemia. A decreased platelet count indicates the client is at risk for bleeding and can be diagnostic of a clotting disorder.[50]

Rubella Titer

A rubella titer is obtained to determine immunity to the disease. If the mother is not immune, the rubella virus can pass through the placenta and infect the fetus. Rubella infection in the fetus can cause multiple congenital anomalies, such as blindness, deafness, cognitive impairment, and heart disease. If the rubella titer does not indicate maternal immunity to the disease, the client is instructed to avoid exposure to anyone with a rash or those who have been diagnosed with rubella. If exposure occurs, the client is instructed to contact the health care provider. A rubella vaccine is prescribed after delivery and before discharge from the postpartum unit. The vaccine is not administered during pregnancy because it is a live vaccine and can transmit the virus to the fetus.[51]

Hepatitis B and C

A hepatitis B and C panel is obtained to determine if the client currently has an active hepatitis infection or has had one in the past. The panel will also indicate if the client has chronic hepatitis. If the client is currently infected with acute or chronic hepatitis, the virus can pass through the placenta and infect the fetus. Hepatitis during pregnancy is associated with a high risk of maternal and newborn morbidity and mortality.[52]

Sexually Transmitted Infections

A venereal disease research laboratory (VDRL) test or rapid plasma reagin (RPR) test is performed to screen the client for syphilis. If the VDRL or RPR test is positive, the treponemal assay blood test is performed to determine if there is a current syphilis infection. Treponema pallidum (the bacterium causing syphilis) crosses the placenta and infects the fetus. Even with treatment, the fetus exposed to syphilis may contract syphilis and may die in utero, especially if the client goes untreated during the first 16 weeks of gestation. Fetuses who are born alive with syphilis have similar congenital anomalies as infants who were exposed to rubella in utero. Treatment of clients with syphilis, their current partner, previous partners, and the newborn is provided based on current Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) guidelines.[53]

An HIV antibody or antigen blood test is performed. If the test is positive, the client will be started on zidovudine, an antiretroviral drug not known to cause congenital anomalies in the fetus. When the parent is treated during pregnancy and the infant is treated immediately after birth, the chance of the infant contracting HIV is less than 1 percent. Testing and treatment of the client, current partner, and previous partners are carried out based on current CDC guidelines.[54]

Testing for gonorrhea and chlamydia infections is routinely done during the first prenatal visit. The test is most often performed using a cervical specimen obtained during the pelvic exam. As with HIV and syphilis, testing and treatment of the client, current partner, and previous partners are recommended based on current CDC guidelines. The bacteria causing gonorrhea and chlamydia do not cross the placenta. However, risk to the fetus occurs once the membranes have ruptured. Prophylactic antibiotics are administered to the newborn’s eyes to prevent infection.[55]

Sexually transmitted infection testing is performed during the initial prenatal visit and during the final weeks of pregnancy. This second testing is most often performed around 36 weeks’ gestation to identify new exposure.[56]

Urinalysis and Urine Drug Screen

In addition to the urine dipstick test performed in the office or clinic, the client’s urine specimen is sent to the laboratory for a urinalysis, urine culture and sensitivity (C&S), and possible urine drug screen (UDS) based on agency policy. The urinalysis and C&S are ordered because urinary frequency is one of the signs of both pregnancy and a urinary tract infection (UTI). A pregnant woman may overlook the symptoms of a UTI or have asymptomatic bacteriuria and go untreated. A UDS may be obtained as a screening tool for current use of substances such as amphetamines, cocaine, marijuana, opiates, phencyclidine, benzodiazepines, barbiturates, methaqualone, and methadone.[57]

If the UDS is positive, the nurse and health care provider will first review the EHR and list of current medications to determine any links to the UDS results. It is important for the nurse or health care provider to discuss the effects of the substance(s) on the client, fetal growth and development, and pregnancy outcome, such as preterm delivery. Throughout the dialog with the client, a nonjudgmental approach is indicated, along with discussion of rehabilitation programs offering supportive services.[58]

Genetic Screening

Initial prenatal lab tests may include screening for genetic diseases like cystic fibrosis and sickle cell trait and disease. Read more about genetic screening tests in the “First Trimester Prenatal Care” section.

Additional Laboratory Tests

Additional laboratory tests may be performed at the first prenatal visit that include, but are not limited to, the Pap smear, gestational glucose screen, complete metabolic panel (CMP), thyroid function panel, and herpes simplex titers. If the client is 21 years or older, a Pap smear is obtained during the pelvic exam to screen for cervical precancerous and cancer cells. This test is done if indicated based on the client’s age and the amount of time since any previous cytology study was performed, as well as the client’s risk status depending on previous Pap smear results. The client’s blood is drawn for a basic metabolic panel if they have a history of medical conditions, such as renal or liver disease, hypertension, or diabetes. Herpes simplex 1 and 2 antibodies are sometimes included with the initial prenatal lab tests to detect a current or previous infection.[59]

The one-hour glucose challenge test (GCT), also known as the gestational diabetes screen, is performed if the client is at increased risk for gestational diabetes. The most common risk factors are obesity, first-degree relative with diabetes, and gestational diabetes with a previous pregnancy. The thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH) level is included in the routine first prenatal visit lab tests because thyroid disease is often overlooked in women. A thyroid panel is performed if the client has thyroid disease.[60]

Health Teaching During First Prenatal Visit

Health teaching provided at the first prenatal visit focuses on health maintenance and preventing complications of pregnancy. The major teaching topics include the following[61]:

- Fetal growth and development

- Review content regarding fetal development in the “Reproduction” section of the “Reproductive Concepts” chapter.

- Physiologic and psychological changes during early pregnancy

- Review content in the “Anatomical, Physiological, and Psychological Changes During Pregnancy” section of this chapter.

- Common discomforts of pregnancy

- Review content in the “Common Discomforts of Pregnancy and Relief Measures” section of this chapter.

- Laboratory testing and results

- Review content in the “Common Initial Prenatal Laboratory and Diagnostic Tests” subsection in the above section of this chapter.

- Signs of complications during the first trimester

- Healthy lifestyle activities and health promotion, including nutrition, weight gain, exercise, substance use, safe medication use, and environmental hazards

- Future routine prenatal care visits

Signs of Complications During the First Trimester

It is not always easy for a pregnant woman to determine if a symptom they are experiencing is a normal discomfort of pregnancy or is a sign of a complication. The nurse investigates the symptoms to differentiate between symptoms that are expected during pregnancy, those that indicate the presence of a medical condition requiring evaluation and treatment, and those that indicate an obstetric complication or emergency requiring immediate evaluation. Symptoms associated with complications of pregnancy discussed at the first prenatal visit are listed in Table 9.7b.[62]

Table 9.7b. Signs of Complications During the First Trimester[63]

| Symptom | Possible Complication |

|---|---|

| Persistent vomiting | Hyperemesis gravidarum |

| Dysuria | Urinary tract infection |

| Intermittent back pain or pelvic pressure | Pyelonephritis or preterm labor |

| Vaginal bleeding | Cervicitis, miscarriage, placenta previa, or placental abruption |

| Temperature >38.3° C (101° F) | Infection |

| Persistent abdominal pain or epigastric pain | Cholelithiasis, liver disease, gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD), preeclampsia, or HELLP (syndrome with hemolysis, elevated liver enzymes, and low platelet counts) |

| Frequent dizziness | Anemia, dehydration, infection, heart disease |

| Leaking of fluid from the vagina | Vaginitis or premature rupture of membranes (PROM) |

Nausea and vomiting frequently occur in the first trimester of pregnancy and are considered normal. However, persistent vomiting accompanied by weight loss or dehydration is not normal, and the client needs further evaluation for hyperemesis gravidarum with possible treatment with intravenous fluids and antiemetics.[64]

Increased urinary frequency is considered normal during pregnancy, but if it is accompanied with dysuria and hematuria, it can indicate a urinary tract infection (UTI) that requires further evaluation. Furthermore, an untreated UTI can progress to pyelonephritis, triggering preterm contractions.[65]

Intermittent back pain and pelvic pressure are common during pregnancy due to the weight of the growing uterus. However, persistent back pain and/or pelvic pressure can be a sign of preterm contractions or UTI that requires further evaluation.[66]

Vaginal bleeding is never a normal symptom during pregnancy and always requires evaluation. Vaginal spotting may occur from a vaginal exam by the health care provider, from cervical erosion due to vaginitis, or from the penis coming in contact with the cervix during sexual intercourse. However, vaginal bleeding may indicate that possible miscarriage, preterm labor, or placental complications such as placenta previa (the placenta is attached in the lower part of the uterus and covers the cervix) or placental abruption (the placenta separates from the uterine wall before childbirth) are occurring.[67]

If a pregnant woman has a temperature greater than 38.3° C (101° F), an infection is present that requires further evaluation. Untreated infection can cause preterm birth.[68]

Pregnant women often experience occasional epigastric or abdominal pain that can be as simple as dyspepsia or flatus. However, severe epigastric pain may also indicate cholelithiasis or hepatic inflammation that are associated with hypertensive disorders of pregnancy. Abdominal pain can also be a sign of placental abruption, appendicitis, or a gastrointestinal infection.[69]

The client may experience an occasional dizzy spell in the early weeks of the pregnancy due to a drop in blood glucose or blood pressure. However, frequent or severe episodes of dizziness may indicate anemia, dehydration, or an underlying heart condition.[70]

Leaking of fluid from the vagina may be caused by stress urinary incontinence or vaginitis. Fluid leaking from the vagina can also be a sign of spontaneous rupture of the membranes (SROM). If SROM occurs in the first trimester, a miscarriage is inevitable.[71]

Self-Care Practices

Hygiene

Hygiene self-care includes bathing practices, handwashing, and dental care. Bathing removes the buildup of oils, bacteria, and dirt on the body, decreasing the risk of disease. It is important for the nurse to include perineal cleansing when discussing bathing practices because of the increase in cervical and vaginal secretions during pregnancy. Frequent handwashing and cleaning under the fingernails by the pregnant woman help prevent illness caused by the microorganisms on multiple surfaces touched every day.[72]

Pregnant women should also be cautioned not to use hot tubs, saunas, or tanning beds during pregnancy. The heat generated by these products raises the pregnant woman’s temperature and the fetal heart rate. The vasodilation of the blood vessels in the skin (as a response to the increase in temperature) pulls blood away from the uterus and can cause orthostatic hypotension upon standing after using these devices.[73]

Pregnancy changes the amount of saliva and increases the vascularity of the gums. These two events place the pregnant woman at risk for gingivitis, dental caries, and loss of teeth. Oral hygiene with a soft-bristled toothbrush after each meal helps to prevent the buildup of bacteria and bleeding gums. Visits with a dental hygienist for routine teeth cleaning are encouraged during pregnancy. If X-rays need to be taken, the pregnant woman should wear a protective apron to shield the abdomen.[74]

Oral hygiene also decreases the risk for periodontitis, which is associated with preterm birth and low birth weight. The symptoms of periodontitis include bleeding gums, loose teeth, and abscess formation. The nurse can assess the mouth, gums, and teeth and refer the pregnant woman to dental services before periodontitis occurs.[75]

Clothing

Self-care related to clothing includes wearing clothes that are not constrictive to the growing uterus such as shapewear. Education also includes the avoidance of knee-high stockings or socks that are tight at the top. These stockings or socks can impede circulation, increasing the risk of DVT in the pregnant woman. Education also includes wearing shoes with low heels to decrease the incidence of lower back ache and risk for falls.[76]

Sleep and Rest

Balancing sleep and rest with work, household expectations, and exercise promotes self-care. During sleep, the body repairs itself and grows. During pregnancy, sleep also promotes fetal growth and development. Education for self-care involving rest and sleep includes the establishment of a consistent bedtime routine and bedtime. Consistency places the body on a schedule, making it easier to fall asleep. Limiting fluid intake for two hours prior to going to bed decreases nocturia and prevents interrupted sleep.[77]

Sexual Activity and Intimacy

Sexual activity during pregnancy can remain normal for couples during an uncomplicated pregnancy. The physiologic changes and psychosocial adaptations that occur during pregnancy may consciously and unconsciously alter the pregnant woman’s interest in sexual activity and intimacy. Sexual activity is not restricted during pregnancy except in cases of vaginal bleeding, placenta previa, rupture of membranes, and preterm contractions. Intimacy involves actions and communication between the pregnant woman and their support person. This can also be a hug, watching a movie together, giving gifts, or just talking.[78]

Employment

Employment may require the pregnant woman to commute or to work from home. Some pregnant women provide full-time care for members of the immediate or extended family. The family members may be siblings of the fetus, related children or children living in the neighborhood, or adults. Pregnancy places a few limitations on job requirements. These limitations include no heavy lifting, specifically no more than 25 pounds after 28 weeks of gestation; avoiding exposure to teratogens, such as chemical fumes and tobacco products; and taking scheduled breaks.[79]

Healthy Lifestyle Choices and Health Promotion

Healthy lifestyle choices during pregnancy include good nutrition, regular exercise, safe medication use, avoidance of substance use, and avoiding environmental exposures to toxic chemicals and teratogens.

Nutrition

Pregnancy changes a person’s nutritional needs, and these needs change as the weeks of gestation progress. The client needs to consume between 70 and 100 grams of protein daily (depending on the client’s BMI and weeks of gestation), 1,000 mg of calcium daily if 19 years of age or older (1,300 mg if less than 19 years of age), 600 mcg of folate every day, and 27 mg of iron each day when pregnant. The client also needs to drink eight to twelve 8-ounce glasses of water every day throughout the pregnancy. See Table 9.7c for an overview of nutritional needs during pregnancy and the best food sources to meet these needs.[80]

Table 9.7c. Nutritional Recommendations During Pregnancy[81]

| Nutrient | Daily Amount | Food Sources | Client and Fetal Benefits |

|---|---|---|---|

| Protein |

|

|

|

| Calcium |

|

|

|

| Folate |

|

|

|

| Iron |

|

|

|

| Vitamin B6 |

|

|

|

| Vitamin B12 |

|

|

|

| Vitamin C |

|

|

|

| Vitamin D |

|

|

|

| Vitamin A |

|

|

|

| Choline |

|

|

|

| Iodine |

|

|

|

| Docosahexaenoic acid (DHA) |

|

|

|

A client’s daily caloric needs during pregnancy are based on their BMI, activity level, and weeks of gestation. A pregnant woman with a normal BMI does not require additional calories during the first trimester of pregnancy. What is important is for the pregnant woman to make their daily intake healthy. During the second trimester of pregnancy, the client should eat around 300 more calories per day. The additional calories can be ingested by drinking two 8-ounce glasses of whole milk. During the third trimester of pregnancy, the client should eat around 400 more calories a day than when not pregnant. Eating one-half of a sandwich with the 8 ounces of milk will supply the additional calories.[82]

The motivation to eat healthy is typically very high for the client who is pregnant. The nurse can provide a pamphlet on eating healthy during pregnancy or pull up the MyPlate.gov website and discuss key information on the nutritional needs during pregnancy.[83]

Nutritional Supplements

Prenatal vitamins with 400 mcg of folic acid are recommended for all pregnant women to keep the mother and fetus healthy and decrease the risk for birth defects. Prenatal vitamins should be taken with a full glass of water or citrus juice to increase absorption. Nurses advise clients to take the vitamins at night if nausea occurs. Although iron is an ingredient in most prenatal vitamins, some pregnant women require additional supplemental iron. Iron tablets are available by prescription or OTC and should be taken only when recommended by the health care provider. Nurses advise clients that iron may turn stools dark brown or black and increase the risk of constipation.[84]

Recommended Weight Gain During Pregnancy

The recommended total weight gain during pregnancy is based on the client’s BMI before conception. The recommended weight gain for clients with a normal BMI is 25 to 35 pounds. For clients whose BMI indicates they were underweight before conception, the recommended total weight gain is 28 to 40 pounds. Clients whose BMI indicates they were overweight before conception are expected to gain 15 to 25 pounds, and clients whose BMI indicates they were obese before conception are expected to gain 11 to 20 pounds. The weight gain during pregnancy is expected to begin after the first trimester of pregnancy.[85] See Table 9.7d for a summary of recommended weight gain during pregnancy based on pre-pregnancy BMI.[86]

Table 9.7d. Recommended Weight Gain During Pregnancy[87]

| Pregestational BMI | Recommended Total Weight Gain | Recommended Weight Gain Each Week During the Second and Third Trimesters |

|---|---|---|

| Underweight:

< 18.5 |

28–40 lb | 1–1.3 lb/week |

| Normal weight:

18.5–24.9 |

25–35 lb | 0.8–1 lb/week |

| Overweight:

25.0–29.9 |

15–25 lb | 0.5–0.7 lb/week |

| Obese:

≥ 30.0 |

11–20 lb | 0.4–0.5 lb/week |

The distribution of weight gained in pregnancy is as follows[88]:

- Breasts: 1–3 pounds

- Uterus: 2 pounds

- Increased fluid volume: 2–3 pounds

- Increased blood volume: 3–4 pounds

- Fat: 6–8 pounds

- Fetus (at term): 7–8 pounds

- Placenta: 1.5 pounds

- Amniotic fluid: 2 pounds

Influence of Religious Beliefs and Rituals on Nutrition

Religious beliefs and rituals may involve fasting on holy days, forbid the ingestion of specific foods and drinks, and specify rituals in food preparation. When a person is pregnant or breastfeeding, the fasting requirements are waived, but many pregnant women elect to fast. The pregnant woman needs to understand the importance of balanced nutritional practices every day to meet the needs of the developing and growing fetus. Food and drink restrictions are taken into consideration when the nurse provides dietary suggestions. Discussing food preparation rituals encourages a dialog about safe handling of food.

Read more about cultural influences on diet in the “Healthy Diets” chapter.

Pica

A significant concern for pregnant women is development of pica, which is a strong craving for and consumption of a nonfood substance. The top three ingested substances with pica are dirt, ice cubes, and cornstarch. Iron-deficiency anemia or other nutritional deficiencies can cause pica.

Exercise

Exercise is recommended during pregnancy even if the client did not exercise prior to conception. For clients who exercised regularly prior to conception, 30 minutes of brisk walking five to seven days a week is advised. Starting slowly is recommended for clients who did not have an exercise routine prior to conception. The client is encouraged to exercise as little as 5 minutes per day and add another 5 minutes every week until a total of 30 minutes each day is reached. Yoga and tai chi classes specifically for pregnant people are other good options.[89]

Safe Over-the-Counter Medication Use

Whenever a pregnant woman is considering taking an over-the-counter (OTC) medication, they should first consult their obstetric care provider regarding its safety. The provider will have an informed discussion with the pregnant woman regarding the benefits and risks of any current or possible prescribed and over-the-counter medication to be taken during the pregnancy.[90]

Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDS) such as ibuprofen and naproxen are contraindicated after 19 weeks of gestation because they can cause oligohydramnios (too little amniotic fluid), renal disease in the fetus, and premature closure of the ductus arteriosus. When not prescribed for risk reduction related to preeclampsia, aspirin is also contraindicated because it can interfere with the clotting cascade and increase the risk of the bleeding.[91]

Acetaminophen is safe to take during pregnancy but is associated with abnormal liver function in clients who exceed 3,000 mg in a 24-hour period, have a history of hypertension prior to pregnancy, or develop a hypertensive complication during pregnancy.[92]

Over-the-counter (OTC) allergy medications such as chlorpheniramine, hydroxyzine, and dexchlorpheniramine, loratadine, and cetirizine are considered safe to take after the first trimester. However, the decongestant pseudoephedrine is not recommended for a pregnant woman to take during the first trimester and is contraindicated in clients with hypertensive disorders because it raises the blood pressure. Dextromethorphan, an antitussive, and guaifenesin, an expectorant, are found in many OTC medications and clients should not exceed the recommended 24-hour dosage.[93]

Substance Use

Research indicates that even small to moderate amounts of daily caffeine intake of 50-200 mcg (about a half cup to 2 cups of coffee) increases the risk for smaller birth size of the fetus. Smaller birth size increases the risk of obesity, heart disease, and diabetes later in life. Women should talk to their health care provider about current recommendations regarding caffeine intake.[94]

Tobacco products, e-cigarettes (vaping), alcohol, marijuana, and recreational drug use are contraindicated throughout the pregnancy. Tobacco products and e-cigarettes contain nicotine, a known vasoconstrictor that affects placental function. Tobacco products are associated with low birth weight, preterm delivery, and sudden infant death syndrome (SIDS). Drinking alcohol during pregnancy is associated with fetal alcohol spectrum disorder (FASD) and can affect cognitive ability, behavior, and facial structure. Marijuana use during pregnancy has been linked to low birth weight and abnormal neurologic development that may not present until the child is of school age. Opioid and illicit substance use in pregnancy is associated with an increased risk of miscarriage, low birth weight, abnormal neurologic development in infants, and SIDS. In addition, illicit substance use during pregnancy is also linked with an increased risk of preterm delivery, placental abruption, intrauterine fetal demise, and withdrawal symptoms in newborn infants.[95]

Environmental Exposures

The same safety concerns and environmental hazards that may affect any person can affect a person who is pregnant. These include, but are not limited to, motor vehicle accidents, pesticides, painting products, heavy metal ingestion, chemical exposure, fall risks, and work hazards. To decrease risk of injury, seat belts should be worn whenever the pregnant woman is a driver or passenger in an automobile, a passenger on an airplane, or an operator of any other type of motor vehicle. Home and work environments should be assessed for fall risks.[96]

When gardening, gloves and long sleeves should be worn, and only organic products should be used. Latex paints are recommended when painting. Exposure to paint thinners, toxic chemicals, or any other toxic ingredients should be avoided throughout the pregnancy because they are associated with an increased risk for miscarriage. The ingestion of mercury and lead is associated with neurologic deficits in the infant. Exposure to secondhand smoke has similar effects on the fetus as if the pregnant woman were smoking.[97]

Pregnant women with cats should be reminded not to change cat litter and avoid being scratched by outdoor cats. Cat feces and nails can transport toxoplasmosis, a known infectious teratogen. Toxoplasmosis can also be transmitted through undercooked meat.[98]

- Giles, A., Prusinski, R., & Wallace, L. (2024). Maternal newborn nursing. OpenStax. https://openstax.org/books/maternal-newborn-nursing/pages/1-introduction ↵

- Giles, A., Prusinski, R., & Wallace, L. (2024). Maternal newborn nursing. OpenStax. https://openstax.org/books/maternal-newborn-nursing/pages/1-introduction ↵

- Giles, A., Prusinski, R., & Wallace, L. (2024). Maternal newborn nursing. OpenStax. https://openstax.org/books/maternal-newborn-nursing/pages/1-introduction ↵

- Giles, A., Prusinski, R., & Wallace, L. (2024). Maternal newborn nursing. OpenStax. https://openstax.org/books/maternal-newborn-nursing/pages/1-introduction ↵

- Giles, A., Prusinski, R., & Wallace, L. (2024). Maternal newborn nursing. OpenStax. https://openstax.org/books/maternal-newborn-nursing/pages/1-introduction ↵

- Giles, A., Prusinski, R., & Wallace, L. (2024). Maternal newborn nursing. OpenStax. https://openstax.org/books/maternal-newborn-nursing/pages/1-introduction ↵

- Giles, A., Prusinski, R., & Wallace, L. (2024). Maternal newborn nursing. OpenStax. https://openstax.org/books/maternal-newborn-nursing/pages/1-introduction ↵

- Giles, A., Prusinski, R., & Wallace, L. (2024). Maternal newborn nursing. OpenStax. https://openstax.org/books/maternal-newborn-nursing/pages/1-introduction ↵

- Giles, A., Prusinski, R., & Wallace, L. (2024). Maternal newborn nursing. OpenStax. https://openstax.org/books/maternal-newborn-nursing/pages/1-introduction ↵

- Giles, A., Prusinski, R., & Wallace, L. (2024). Maternal newborn nursing. OpenStax. https://openstax.org/books/maternal-newborn-nursing/pages/1-introduction ↵

- Giles, A., Prusinski, R., & Wallace, L. (2024). Maternal newborn nursing. OpenStax. https://openstax.org/books/maternal-newborn-nursing/pages/1-introduction ↵

- Giles, A., Prusinski, R., & Wallace, L. (2024). Maternal newborn nursing. OpenStax. https://openstax.org/books/maternal-newborn-nursing/pages/1-introduction ↵

- MedlinePlus [Internet]. (2023). Congenital toxoplasmosis. https://medlineplus.gov/ency/article/001360.htm ↵

- Giles, A., Prusinski, R., & Wallace, L. (2024). Maternal newborn nursing. OpenStax. https://openstax.org/books/maternal-newborn-nursing/pages/1-introduction ↵

- Giles, A., Prusinski, R., & Wallace, L. (2024). Maternal newborn nursing. OpenStax. https://openstax.org/books/maternal-newborn-nursing/pages/1-introduction ↵

- RegisteredNurseRN. (2016, December 15). Naegele’s Rule example with practice questions for maternity nursing NCLEX review (Nagele’s Rule) [Video]. YouTube. All rights reserved. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=N0iqVBX5F9s ↵

- Giles, A., Prusinski, R., & Wallace, L. (2024). Maternal newborn nursing. OpenStax. https://openstax.org/books/maternal-newborn-nursing/pages/1-introduction ↵

- Giles, A., Prusinski, R., & Wallace, L. (2024). Maternal newborn nursing. OpenStax. https://openstax.org/books/maternal-newborn-nursing/pages/1-introduction ↵

- Giles, A., Prusinski, R., & Wallace, L. (2024). Maternal newborn nursing. OpenStax. https://openstax.org/books/maternal-newborn-nursing/pages/1-introduction ↵

- RegisteredNurseRN. (2020, January 24). Gravidity and parity examples maternity nursing NCLEX review (Gravida & para) [Video]. YouTube. All rights reserved. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4YlVvP5Z4XM ↵

- Giles, A., Prusinski, R., & Wallace, L. (2024). Maternal newborn nursing. OpenStax. https://openstax.org/books/maternal-newborn-nursing/pages/1-introduction ↵

- Giles, A., Prusinski, R., & Wallace, L. (2024). Maternal newborn nursing. OpenStax. https://openstax.org/books/maternal-newborn-nursing/pages/1-introduction ↵

- Giles, A., Prusinski, R., & Wallace, L. (2024). Maternal newborn nursing. OpenStax. https://openstax.org/books/maternal-newborn-nursing/pages/1-introduction ↵

- Giles, A., Prusinski, R., & Wallace, L. (2024). Maternal newborn nursing. OpenStax. https://openstax.org/books/maternal-newborn-nursing/pages/1-introduction ↵

- Giles, A., Prusinski, R., & Wallace, L. (2024). Maternal newborn nursing. OpenStax. https://openstax.org/books/maternal-newborn-nursing/pages/1-introduction ↵

- Giles, A., Prusinski, R., & Wallace, L. (2024). Maternal newborn nursing. OpenStax. https://openstax.org/books/maternal-newborn-nursing/pages/1-introduction ↵

- University of New Mexico Health. (2023). How pregnancy affects the heart: Normal symptoms and when to call your doctor. https://unmhealth.org/stories/2023/05/how-pregnancy-affects-heart-symptoms-when-to-call-doctor.html ↵

- Giles, A., Prusinski, R., & Wallace, L. (2024). Maternal newborn nursing. OpenStax. https://openstax.org/books/maternal-newborn-nursing/pages/1-introduction ↵

- Giles, A., Prusinski, R., & Wallace, L. (2024). Maternal newborn nursing. OpenStax. https://openstax.org/books/maternal-newborn-nursing/pages/1-introduction ↵

- Giles, A., Prusinski, R., & Wallace, L. (2024). Maternal newborn nursing. OpenStax. https://openstax.org/books/maternal-newborn-nursing/pages/1-introduction ↵

- Giles, A., Prusinski, R., & Wallace, L. (2024). Maternal newborn nursing. OpenStax. https://openstax.org/books/maternal-newborn-nursing/pages/1-introduction ↵

- Giles, A., Prusinski, R., & Wallace, L. (2024). Maternal newborn nursing. OpenStax. https://openstax.org/books/maternal-newborn-nursing/pages/1-introduction ↵

- Giles, A., Prusinski, R., & Wallace, L. (2024). Maternal newborn nursing. OpenStax. https://openstax.org/books/maternal-newborn-nursing/pages/1-introduction ↵

- Giles, A., Prusinski, R., & Wallace, L. (2024). Maternal newborn nursing. OpenStax. https://openstax.org/books/maternal-newborn-nursing/pages/1-introduction ↵

- University of New Mexico Health. (2023). How pregnancy affects the heart: Normal symptoms and when to call your doctor. https://unmhealth.org/stories/2023/05/how-pregnancy-affects-heart-symptoms-when-to-call-doctor.html ↵

- Giles, A., Prusinski, R., & Wallace, L. (2024). Maternal newborn nursing. OpenStax. https://openstax.org/books/maternal-newborn-nursing/pages/1-introduction ↵

- Giles, A., Prusinski, R., & Wallace, L. (2024). Maternal newborn nursing. OpenStax. https://openstax.org/books/maternal-newborn-nursing/pages/1-introduction ↵

- Giles, A., Prusinski, R., & Wallace, L. (2024). Maternal newborn nursing. OpenStax. https://openstax.org/books/maternal-newborn-nursing/pages/1-introduction ↵

- Giles, A., Prusinski, R., & Wallace, L. (2024). Maternal newborn nursing. OpenStax. https://openstax.org/books/maternal-newborn-nursing/pages/1-introduction ↵

- “acff9487a07586ed5313844c81cc109053e2bf19” by OpenStax is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/maternal-newborn-nursing/pages/11-1-first-prenatal-visit ↵

- Giles, A., Prusinski, R., & Wallace, L. (2024). Maternal newborn nursing. OpenStax. https://openstax.org/books/maternal-newborn-nursing/pages/1-introduction ↵

- Geeky Medics. (2019, September 21). Pregnancy abdomen examination (a.k.a. Obstetric abdominal examination) [Video]. YouTube. All rights reserved. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-pkkgBX7OFQ ↵

- Giles, A., Prusinski, R., & Wallace, L. (2024). Maternal newborn nursing. OpenStax. https://openstax.org/books/maternal-newborn-nursing/pages/1-introduction ↵

- Giles, A., Prusinski, R., & Wallace, L. (2024). Maternal newborn nursing. OpenStax. https://openstax.org/books/maternal-newborn-nursing/pages/1-introduction ↵

- Giles, A., Prusinski, R., & Wallace, L. (2024). Maternal newborn nursing. OpenStax. https://openstax.org/books/maternal-newborn-nursing/pages/1-introduction ↵

- Giles, A., Prusinski, R., & Wallace, L. (2024). Maternal newborn nursing. OpenStax. https://openstax.org/books/maternal-newborn-nursing/pages/1-introduction ↵

- “f9922f4a3bff786d5e7f69f61bac528b3ab4dfc5” by OpenStax is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/maternal-newborn-nursing/pages/11-1-first-prenatal-visit ↵

- Giles, A., Prusinski, R., & Wallace, L. (2024). Maternal newborn nursing. OpenStax. https://openstax.org/books/maternal-newborn-nursing/pages/1-introduction ↵

- Giles, A., Prusinski, R., & Wallace, L. (2024). Maternal newborn nursing. OpenStax. https://openstax.org/books/maternal-newborn-nursing/pages/1-introduction ↵

- Giles, A., Prusinski, R., & Wallace, L. (2024). Maternal newborn nursing. OpenStax. https://openstax.org/books/maternal-newborn-nursing/pages/1-introduction ↵

- Giles, A., Prusinski, R., & Wallace, L. (2024). Maternal newborn nursing. OpenStax. https://openstax.org/books/maternal-newborn-nursing/pages/1-introduction ↵

- Giles, A., Prusinski, R., & Wallace, L. (2024). Maternal newborn nursing. OpenStax. https://openstax.org/books/maternal-newborn-nursing/pages/1-introduction ↵

- Giles, A., Prusinski, R., & Wallace, L. (2024). Maternal newborn nursing. OpenStax. https://openstax.org/books/maternal-newborn-nursing/pages/1-introduction ↵

- Giles, A., Prusinski, R., & Wallace, L. (2024). Maternal newborn nursing. OpenStax. https://openstax.org/books/maternal-newborn-nursing/pages/1-introduction ↵

- Giles, A., Prusinski, R., & Wallace, L. (2024). Maternal newborn nursing. OpenStax. https://openstax.org/books/maternal-newborn-nursing/pages/1-introduction ↵

- Giles, A., Prusinski, R., & Wallace, L. (2024). Maternal newborn nursing. OpenStax. https://openstax.org/books/maternal-newborn-nursing/pages/1-introduction ↵

- Giles, A., Prusinski, R., & Wallace, L. (2024). Maternal newborn nursing. OpenStax. https://openstax.org/books/maternal-newborn-nursing/pages/1-introduction ↵

- Giles, A., Prusinski, R., & Wallace, L. (2024). Maternal newborn nursing. OpenStax. https://openstax.org/books/maternal-newborn-nursing/pages/1-introduction ↵

- Giles, A., Prusinski, R., & Wallace, L. (2024). Maternal newborn nursing. OpenStax. https://openstax.org/books/maternal-newborn-nursing/pages/1-introduction ↵

- Giles, A., Prusinski, R., & Wallace, L. (2024). Maternal newborn nursing. OpenStax. https://openstax.org/books/maternal-newborn-nursing/pages/1-introduction ↵

- Giles, A., Prusinski, R., & Wallace, L. (2024). Maternal newborn nursing. OpenStax. https://openstax.org/books/maternal-newborn-nursing/pages/1-introduction ↵

- Giles, A., Prusinski, R., & Wallace, L. (2024). Maternal newborn nursing. OpenStax. https://openstax.org/books/maternal-newborn-nursing/pages/1-introduction ↵

- Giles, A., Prusinski, R., & Wallace, L. (2024). Maternal newborn nursing. OpenStax. https://openstax.org/books/maternal-newborn-nursing/pages/1-introduction ↵

- Giles, A., Prusinski, R., & Wallace, L. (2024). Maternal newborn nursing. OpenStax. https://openstax.org/books/maternal-newborn-nursing/pages/1-introduction ↵

- Giles, A., Prusinski, R., & Wallace, L. (2024). Maternal newborn nursing. OpenStax. https://openstax.org/books/maternal-newborn-nursing/pages/1-introduction ↵

- Giles, A., Prusinski, R., & Wallace, L. (2024). Maternal newborn nursing. OpenStax. https://openstax.org/books/maternal-newborn-nursing/pages/1-introduction ↵

- Giles, A., Prusinski, R., & Wallace, L. (2024). Maternal newborn nursing. OpenStax. https://openstax.org/books/maternal-newborn-nursing/pages/1-introduction ↵

- Giles, A., Prusinski, R., & Wallace, L. (2024). Maternal newborn nursing. OpenStax. https://openstax.org/books/maternal-newborn-nursing/pages/1-introduction ↵

- Giles, A., Prusinski, R., & Wallace, L. (2024). Maternal newborn nursing. OpenStax. https://openstax.org/books/maternal-newborn-nursing/pages/1-introduction ↵

- Giles, A., Prusinski, R., & Wallace, L. (2024). Maternal newborn nursing. OpenStax. https://openstax.org/books/maternal-newborn-nursing/pages/1-introduction ↵

- Giles, A., Prusinski, R., & Wallace, L. (2024). Maternal newborn nursing. OpenStax. https://openstax.org/books/maternal-newborn-nursing/pages/1-introduction ↵

- Giles, A., Prusinski, R., & Wallace, L. (2024). Maternal newborn nursing. OpenStax. https://openstax.org/books/maternal-newborn-nursing/pages/1-introduction ↵

- Giles, A., Prusinski, R., & Wallace, L. (2024). Maternal newborn nursing. OpenStax. https://openstax.org/books/maternal-newborn-nursing/pages/1-introduction ↵

- Giles, A., Prusinski, R., & Wallace, L. (2024). Maternal newborn nursing. OpenStax. https://openstax.org/books/maternal-newborn-nursing/pages/1-introduction ↵

- Giles, A., Prusinski, R., & Wallace, L. (2024). Maternal newborn nursing. OpenStax. https://openstax.org/books/maternal-newborn-nursing/pages/1-introduction ↵

- Giles, A., Prusinski, R., & Wallace, L. (2024). Maternal newborn nursing. OpenStax. https://openstax.org/books/maternal-newborn-nursing/pages/1-introduction ↵

- Giles, A., Prusinski, R., & Wallace, L. (2024). Maternal newborn nursing. OpenStax. https://openstax.org/books/maternal-newborn-nursing/pages/1-introduction ↵

- Giles, A., Prusinski, R., & Wallace, L. (2024). Maternal newborn nursing. OpenStax. https://openstax.org/books/maternal-newborn-nursing/pages/1-introduction ↵

- Giles, A., Prusinski, R., & Wallace, L. (2024). Maternal newborn nursing. OpenStax. https://openstax.org/books/maternal-newborn-nursing/pages/1-introduction ↵

- Giles, A., Prusinski, R., & Wallace, L. (2024). Maternal newborn nursing. OpenStax. https://openstax.org/books/maternal-newborn-nursing/pages/1-introduction ↵

- Giles, A., Prusinski, R., & Wallace, L. (2024). Maternal newborn nursing. OpenStax. https://openstax.org/books/maternal-newborn-nursing/pages/1-introduction ↵

- Giles, A., Prusinski, R., & Wallace, L. (2024). Maternal newborn nursing. OpenStax. https://openstax.org/books/maternal-newborn-nursing/pages/1-introduction ↵