8.5 Reproductive Screening

Health care providers and nurses assess a couple’s risk for having an infant with birth defects by reviewing their family and personal health history before conception or at the beginning of pregnancy, as well as recommending reproductive screening. Reproductive screening is recommended for healthy couples to identify their risk of having children with genetic diseases. Screening tests do not definitively diagnose a genetic disease in a fetus, but they identify increased risk for specific disorders so that additional diagnostic tests can be performed.[1]

The quad screen is an example of a maternal blood screen test to detect an increased risk of the fetus having a birth defect such as Down syndrome. The quad screen measures maternal blood for alpha fetoprotein (AFP), estriol, human chorionic gonadoptropin (hCG), and inhibin A. AFP requires a blood sample to be drawn from a pregnant woman between 15- and 20-weeks’ gestation. If the results are abnormal, further diagnostic testing may include a diagnostic ultrasound or amniocentesis. Amniocentesis is a procedure that removes and tests a small sample of cells from amniotic fluid, the fluid that surrounds the fetus in the uterus, to diagnose genetic disorders like Down syndrome and neural tube defects. Down syndrome, also called trisomy 21, is a common chromosome abnormality that causes a characteristic appearance, hypotonia, and cognitive impairment. Neural tube defects are a common birth defect in the United States that can cause anencephaly or spina bifida. Anencephaly is a lethal condition where the fetal brain and skull do not form properly. Spina bifida is a condition that occurs when the neural tube doesn’t close as it should, resulting in damage to the spinal cord and nerves. The survival rates and degree of physical and intellectual disabilities in children with spina bifida vary with the location and severity of the damage.[2],[3]

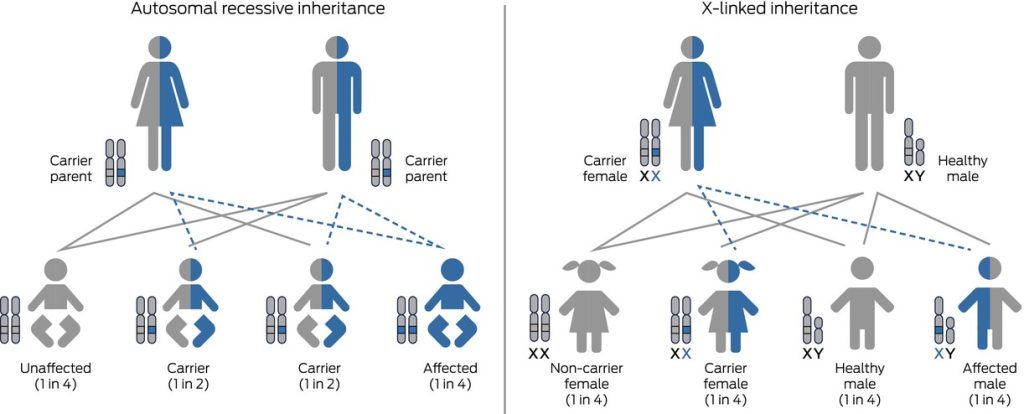

There are many new and expanding screening tests that provide couples who are pregnant or plan to become pregnant with information about potential illness of their fetus. Reproductive genetic carrier screening (RGCS) screens healthy couples for increased risk of having a child with a recessive genetic condition that causes serious childhood disease. Recessive genetic conditions are caused by autosomal recessive inheritance or X-linked inheritance.[4] See Figure 8.19[5] for an illustration of autosomal recessive inheritance and X-linked inheritance patterns.

Examples of recessive genetic conditions that cause serious childhood disease include cystic fibrosis, spinal muscular atrophy, fragile X syndrome, thalassemias, and hemoglobinopathies. Cystic fibrosis is a life-limiting autosomal recessive condition that causes severe damage to the lungs, digestive system, and other organs in the body. Spinal muscular atrophy affects the central nervous system, peripheral nervous system, and voluntary muscle movement and is a frequent cause of infant mortality. Fragile X syndrome is a common cause of X-linked intellectual disability. Thalassemia and hemoglobinopathies cause a lack of normal hemoglobin, resulting in oxygenation problems.

The goal of RGCS is to provide individuals with meaningful information that they can use to guide pregnancy planning based on their personal values.[6] When provided before conception or early in pregnancy, RGCS allows couples to make informed reproductive choices for current or future pregnancies. It can reduce the chance of having a child with a genetic disease or allow optimization of health care during an ongoing pregnancy.[7] However, screening for genetic conditions is optional, and after counseling, clients may decline any or all genetic carrier screening.[8]

According to the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, if a woman is found to be a genetic carrier for a specific condition, her reproductive partner should be offered screening so that accurate genetic counseling regarding the risk of having an affected child can be provided. If a carrier couple is identified before pregnancy (i.e., both parents are carriers for the same genetic condition), genetic counseling is encouraged. Genetic counselors describe the risk for specific genetic condition(s) and reproductive options such as donor gametes.[9]

Psychosocial risks of reproductive screening have been identified, including parents’ lack of understanding of screening results, significant stress and anxiety, and reproductive decision-making that does not align with the individual’s values.[10] The perceived threat to the developing fetus, coupled with the feeling of helplessness that can occur as the diagnostic process continues, can intensify the feelings of anxiety for the pregnant woman and couple.[11] There are also ethical concerns regarding RGCS, including the influence of socially constructed models of disability and difference.[12]

Prenatal RGCS does not replace newborn screening. Newborn screening is discussed in the “Applying the Nursing Process and Clinical Judgment Model to Newborn Care” section of the “Healthy Newborn” chapter.

The Nurse’s Role in Reproductive Screening

Nurses may be involved in reproductive screening in a number of ways. They may be involved in planning, implementing, administering, or evaluating screening and testing programs, or they may care for clients undergoing or considering screening. Nurses providing direct client care must be aware of the availability and potential impact of screening techniques so they can provide appropriate information and support and reduce potential psychological impact.[13]

Informed consent is the first step in the screening process. Offering reproductive screening is considered a standard of care, although it is voluntary for clients to participate, and they have the option to refuse screening. As clients consider reproductive screening, nurses should be prepared to provide accurate and sensitive answers to the following common questions[14]:

- What are the conditions for which the test is designed to detect increased risk? Many conditions may be unfamiliar to the client. Written information about the tests and conditions being screened should be available to supplement discussion with the health care provider.

- What diagnostic tests will be suggested by the health care provider if the screening test is positive? Nurses can help the client understand that the screening test may be only the first step, and other tests such as a diagnostic ultrasound and/or amniocentesis will be offered if the screening results are abnormal. This is the time to explore what the screening will mean for the couple in the context of their personal values and beliefs. Discussions about abortion may occur at this time because treatment is not available during pregnancy. However, the client may feel there is a benefit in knowing about a serious birth defect even when treatment before birth is not available. For example, the existence of a fetus’s serious birth defect will allow for planning delivery at a center where appropriate care is available for the infant. Additionally, having time before delivery to consult with specialists and make decisions about treatment options for the newborn is important to many families.

- What are the client’s reasons for accepting or rejecting reproductive screening? Some women accept reproductive screening due to concern about potentially harmful effects from exposures to medications or environmental agents. Nurses can clarify what is known about exposure to specific agents so that clients understand what information reproductive screening can and cannot provide. In some cases, it may be necessary to refer clients to specialists for additional evaluation and counseling.

- How does the client prefer to be notified of the screening results? The nurse should document how the client prefers to receive the screening results. Although a telephone call or letter may be adequate to report negative results, abnormal results can invoke an intense emotional response that requires privacy.

- What follow-up will occur if there are abnormal screening results? If additional tests or a referral to a specialist is indicated based on screening results, appointments should be made at the earliest convenience for the client. The nurse should emphasize that the client should take time to consider any recommended invasive diagnostic testing and/or pregnancy termination, and follow-up decisions should not be made until both parents have adequate information.

Due to rapidly evolving advancements in reproductive genetic screening, nurses are not likely to be able to maintain in-depth knowledge about all types of screening. Instead, nurses involved in direct prenatal care should establish their own network of resources, such as resources within a screening laboratory, perinatal centers where diagnostic testing is performed, genetic counseling resources, and local support groups for families experiencing birth defects and perinatal losses. These resources will help the nurse to provide the most up-to-date information and support to clients.[15]

Reproductive Health Screening

In addition to prospective parents screening for potential genetic defects in children, all clients are encouraged to participate in reproductive health screening for issues such as sexually transmitted infections (STIs), cervical cancer, and prostate cancer.

A nurse or other medical professional may serve as a “chaperone” during an examination or procedure involving the genitals and serve as a witness for the provider. A chaperone should be provided regardless of the provider or client gender, according to the comfort of the client.[16]

Screening for Sexually Transmitted Infections

Sexually transmitted diseases that can be transmitted between partners and/or between mothers and fetuses are discussed in the “Sexually Transmitted Infections” section. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) has established the following screening guidelines to protect people and their infants from potentially lifelong and serious effects of STIs[17]:

- All people between the ages of 13-64 should be tested at least once for human immunodeficiency virus (HIV).

- All sexually active women younger than age 25, women with new or multiple partners, or women whose partners have an STI should be tested for gonorrhea and chlamydia annually.

- All pregnant clients should be tested for gonorrhea, chlamydia, syphilis, HIV, hepatitis B, and hepatitis C.

- All men who have sex with men should be tested for HIV, syphilis, gonorrhea, and chlamydia at least yearly. Men with multiple or anonymous partners need more frequent testing. If living with HIV, men in this category should be tested at least yearly for hepatitis C.

- Anyone who is sexually active and shares needles should be tested for HIV yearly.

- People who engage in oral or anal sex may be at risk for throat or rectal disease and should speak with their health care provider about screening tests.

Screening for Cervical Cancer

Women should be routinely screened for cervical cancer with a Papanicolaou and HPV test. Review information about cervical cancer screening in the “Secondary Prevention” section of the “Healthy Lifestyles” chapter.

Screening for Testicular and Prostate Cancer

The U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) reviewed the evidence from cancer screenings and determined there is no reduction in cancer deaths from routine screening for prostate or testicular cancers.

Testicular cancer (a tumor of the testis) is the most common cancer among males aged 15 to 34 years. However, with an annual incidence rate of 5.4 cases per 100,000 males, testicular cancer is relatively rare compared with other types of cancer. Most cases of testicular cancer are discovered accidentally by clients or their partners. Potential harms associated with screening for testicular cancer include false-positive results, anxiety, and harms from diagnostic tests or procedures. The United States Preventative Services Task Force (USPSTF) states there is little or no benefit for routine screening for testicular cancer.[18] However, nurses do teach clients to report concerning symptoms to their health care provider.

Prostate cancer is a common cancer affecting approximately 11% of men in the United States, with the lifetime risk of dying of prostate cancer of 2.5%. Most prostate cancers are slow growing and asymptomatic. In fact, most men with prostate cancer will die of other causes before they become symptomatic. The Prostate-Specific Antigen (PSA) blood test can be performed, but elevated PSA levels can be caused by other conditions, including benign prostatic hyperplasia or inflammation of the prostate (prostatitis), in addition to cancer. Health care providers may perform a digital rectal exam to palpate the prostate for abnormalities, but this test is not specific. Additionally, the treatment for prostate cancer can be harmful and cause incontinence and erectile dysfunction. For these reasons, the USPSTF does not recommend screening for prostate cancer unless a man expresses a preference for screening after being informed of these potential risks.[19] Nurses teach clients to report concerning symptoms to their health care providers.

- Grant, S. S. (2000). Prenatal genetic screening. The Online Journal of Issues in Nursing, 5(3). https://doi.org/10.3912/OJIN.Vol5No03Man02 ↵

- Grant, S. S. (2000). Prenatal genetic screening. The Online Journal of Issues in Nursing, 5(3). https://doi.org/10.3912/OJIN.Vol5No03Man02 ↵

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (n.d.). About spina bifida. https://www.cdc.gov/spina-bifida/about/ ↵

- Rogers, A. P., Fitzgerald, L., Liebelt, J., & Barnett, C. (2024). Medicare-funded reproductive genetic carrier screening in Australia has arrived: Are we ready? Medical Journal of Australia, 220(8), 394–397. https://doi.org/10.5694/mja2.52261 ↵

- “mja252261-gra-0001-m” from Rogers, A. P., Fitzgerald, L., Liebelt, J., & Barnett, C. (2024). Medicare‐funded reproductive genetic carrier screening in Australia has arrived: Are we ready? Medical Journal of Australia, 220(8), 394–397. https://doi.org/10.5694/mja2.52261 is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. (2017). Committee opinion No. 690 summary: Carrier screening in the age of genomic medicine. Obstetrics & Gynecology, 129(3), 595-596. http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/AOG.0000000000001951 ↵

- Rogers, A. P., Fitzgerald, L., Liebelt, J., & Barnett, C. (2024). Medicare-funded reproductive genetic carrier screening in Australia has arrived: Are we ready? Medical Journal of Australia, 220(8), 394–397. https://doi.org/10.5694/mja2.52261 ↵

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. (2017). Committee opinion No. 690 summary: Carrier screening in the age of genomic medicine. Obstetrics & Gynecology, 129(3), 595-596. http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/AOG.0000000000001951 ↵

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. (2017). Committee opinion No. 690 summary: Carrier screening in the age of genomic medicine. Obstetrics & Gynecology, 129(3), 595-596. http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/AOG.0000000000001951 ↵

- King, E., Halliday, J., Archibald, A. D., Delatycki, M., Barlow-Stewart, K., Newson, A. J., & McClaren, B. J. (2021). Development and use of the Australian reproductive genetic carrier screening decision aid. European Journal of Human Genetics, 30, 194-202. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41431-021-00991-x ↵

- Grant, S. S. (2000). Prenatal genetic screening. The Online Journal of Issues in Nursing, 5(3). https://doi.org/10.3912/OJIN.Vol5No03Man02 ↵

- King, E., Halliday, J., Archibald, A. D., Delatycki, M., Barlow-Stewart, K., Newson, A. J., & McClaren, B. J. (2021). Development and use of the Australian reproductive genetic carrier screening decision aid. European Journal of Human Genetics, 30, 194-202. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41431-021-00991-x ↵

- Grant, S. S. (2000). Prenatal genetic screening. The Online Journal of Issues in Nursing, 5(3). https://doi.org/10.3912/OJIN.Vol5No03Man02 ↵

- Grant, S. S. (2000). Prenatal genetic screening. The Online Journal of Issues in Nursing, 5(3). https://doi.org/10.3912/OJIN.Vol5No03Man02 ↵

- Grant, S. S. (2000). Prenatal genetic screening. The Online Journal of Issues in Nursing, 5(3). https://doi.org/10.3912/OJIN.Vol5No03Man02 ↵

- Mulcahy, L. (2023). Chaperones for physical exams? Doctors and patients weigh in. Medscape. https://www.medscape.com/viewarticle/994705 ↵

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (n.d.). Getting tested for STIs. https://www.cdc.gov/sti/testing/ ↵

- U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. (2011). Testicular cancer: Screening. https://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/recommendation/testicular-cancer-screening ↵

- U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. (2018). Prostate cancer: Screening. https://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/recommendation/prostate-cancer-screening ↵

Tests and assessments conducted to evaluate reproductive health, including fertility and potential genetic conditions.

An example of a maternal blood screen test to detect an increased risk of the fetus having a birth defect such as Down Syndrome. The quad screen measures maternal blood for alpha fetoprotein (AFP), estriol, human chorionic gonadoptropin (hCG) and inhibin A.

A prenatal procedure where amniotic fluid is extracted from the uterus for testing, often used to detect genetic disorders.

A genetic condition that affects brain and body development due to an extra chromosome number 21.

Severe birth defects of the brain and spine that occur when the neural tube, an embryonic structure that develops into the spinal cord and brain, doesn't close completely during pregnancy.

A lethal condition where the fetal brain and skull do not form properly.

A neural tube defect where the spine does not form or close correctly during fetal development in utero.

A genetic test used to identify whether an individual carries a gene for certain inherited disorders that could be passed on to their offspring.

A genetic disorder that affects the respiratory and digestive systems, leading to the production of thick mucus that can cause severe respiratory and digestive problems.

A genetic disorder that causes weakness and atrophy of skeletal muscles due to the loss of motor neurons in the spinal cord.

A genetic condition that causes intellectual disabilities, behavioral challenges, and physical characteristics due to a mutation in the FMR1 gene.

A genetic blood disorder that causes the body to produce an abnormal form of hemoglobin, leading to anemia.

A group of disorders affecting the hemoglobin in red blood cells, such as sickle cell disease or thalassemia.