8.3 Sexual Development Across the Life Span

Puberty is the stage of development in which individuals become sexually mature. Although the outcomes of puberty for boys and girls are very different, the hormonal control of the process is very similar. The sequence of changes that occur is predictable for male and female adolescents in the development of secondary sex characteristics, the physical changes that serve roles in reproduction.

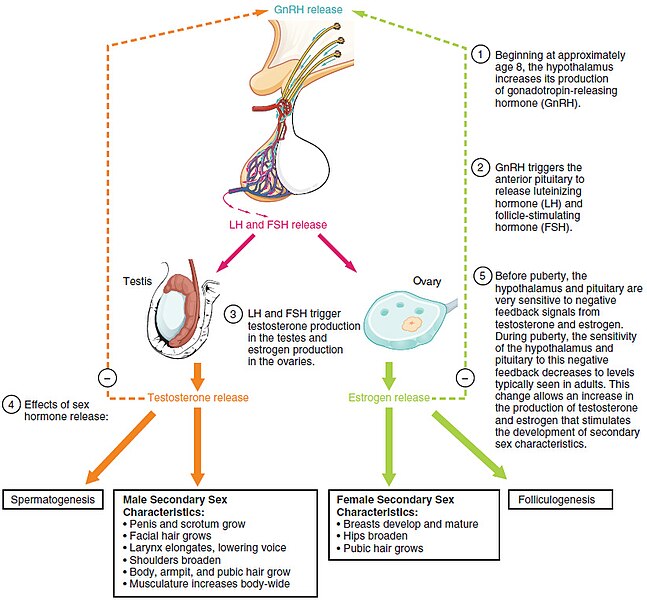

As shown in Figure 8.9,[1] hormones released from the hypothalamus (gonadotropin releasing hormone [GnRH]), the anterior pituitary (luteinizing hormone [LH] and follicle-stimulating hormone [FSH]), and the gonads (either testosterone or estrogen) are responsible for the maturation of male and female reproductive systems. Gonads are the components of the reproductive system that produce gametes. In females, the ovaries are gonads that produce estrogen. In males, the testes are gonads that produce testosterone.[2]

The first changes that occur during sexual development begin around the age of eight or nine when the production of LH becomes detectable in both genders. LH release occurs primarily at night during sleep and precedes the physical changes of puberty by several years. In pre-pubertal children, the negative feedback system in the hypothalamus and pituitary is very sensitive. This means that very low concentrations of androgens and estrogens in the bloodstream will negatively feed back to the hypothalamus and pituitary, keeping their production of GnRH, LH, and FSH low.[3]

As a child approaches puberty, two changes in sensitivity occur. The first is a decrease of sensitivity in the hypothalamus and pituitary to negative feedback, meaning that it takes increasingly larger concentrations of hormones in the blood to stop the production of LH and FSH. The second change is an increase in sensitivity of the gonads to the FSH and LH signals, meaning the gonads become more responsive to these gonadotropins. As a result of these two changes, LH and FSH levels slowly increase and cause the enlargement and maturation of the gonads. Maturation of the gonads leads to secretion of higher levels of sex hormones and the initiation of spermatogenesis and folliculogenesis.[4]

In addition to age, multiple factors can affect the age of onset of puberty, including genetics, environment, and psychological stress. One of the most important influences is nutrition. Historical data demonstrates the effect of better and more consistent nutrition on the age of menarche in girls in the United States, which decreased from an average age of approximately 17 years of age in 1860 to the current age of approximately 12.75 years. Some studies indicate a link between puberty onset and the amount of stored fat in an individual. This effect is more pronounced in girls but has been documented in both sexes. Body fat, corresponding with secretion of leptin hormone by adipose cells, appears to have a strong role in determining menarche. However, girls who are lean and highly active, such as gymnasts, often experience a delay in the onset of puberty.[5]

Signs of Puberty

Initially, there is a growth spurt, followed by the first part of sexual maturity where primary sexual characteristics develop and changes to the internal reproductive organs occur. Primary sexual characteristics are present at birth, such as ovaries in females and testes in males.

As a girl reaches puberty, typically the first visible change is the development of the breast tissue. This is followed by the growth of axillary and pubic hair. A growth spurt normally starts at approximately age 9 to 11 years old and may last two years or more. During this time, a girl’s height can increase approximately three inches per year, and menarche, the first menstruation cycle, begins. The female gametes are stored in the ovaries and are present at birth but are immature. Beginning at puberty, one ovum ripens and is released about every 28 days during the menstrual cycle.[6],[7]

In boys, the growth of the testes is typically the first physical sign of the beginning of puberty, which is followed by growth and pigmentation of the scrotum and growth of the penis. The next step is the growth of hair, including armpit, pubic, chest, and facial hair. Testosterone stimulates the growth of the larynx and thickening and lengthening of the vocal folds, which causes the voice to drop in pitch. The first fertile ejaculations typically appear at approximately 15 years of age, but this age can vary widely across individual boys. Unlike the early growth spurt observed in females, the male growth spurt occurs toward the end of puberty, at approximately age 11 to 13, when a boy’s height can increase as much as four inches per year. In some males, pubertal development can continue through the early 20s.[8]

The second part of sexual maturity occurs with the visibility of secondary sexual characteristics. These are physical changes not directly linked to reproduction but signal sexual maturity. For males, this includes broader shoulders and a lower voice as the larynx grows. Hair becomes coarser and darker, and hair growth occurs in the pubic area, under the arms, and on the face.

For females breast development begins around age ten, although full development takes several years. Hips broaden and pubic and underarm hair develops and also becomes darker and coarser. Sex hormone concentrations contribute to the development and function of secondary sexual characteristics. See Table 8.3a for a summary of secondary sexual characteristics in males and females.

Table 8.3a. Secondary Sex Characteristics

| Male | Female |

|---|---|

| Increased larynx size and deepening of the voice | Deposition of fat, predominantly in the breast and hips |

| Increased muscular development | Breast development |

| Growth of facial, axillary, and pubic hair and increased growth of body hair | Broadening of the pelvis and growth of axillary and pubic hair |

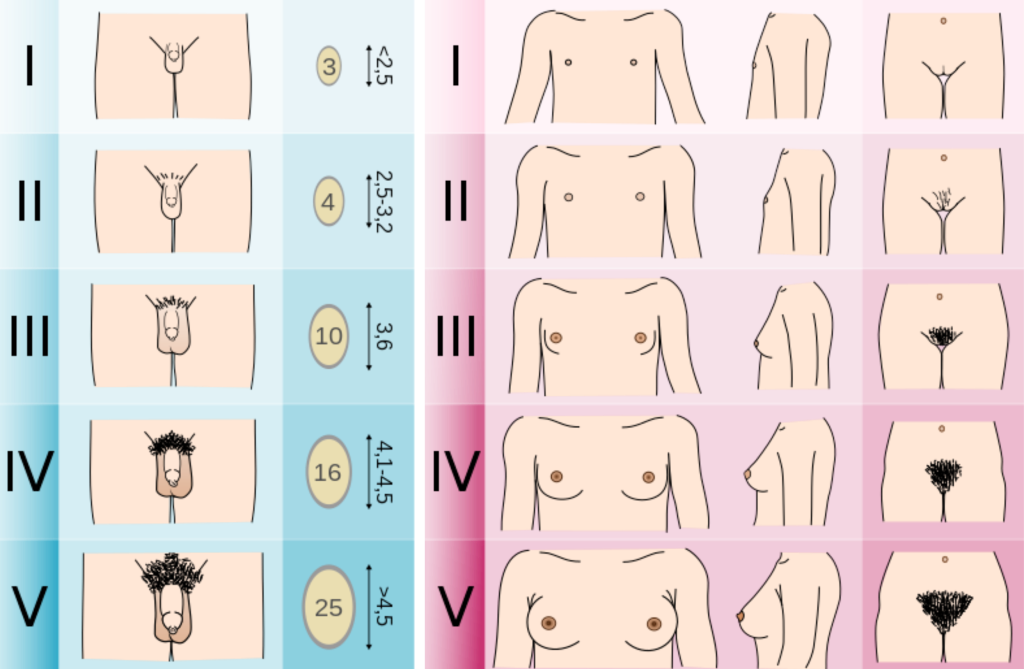

The Tanner Staging Scale is an objective classification system used by nurses and other health care providers to track and document the development of a client’s secondary sex characteristics as they develop through childhood and puberty to an adult. See Figure 8.10[9] for an illustration of the Tanner Staging Scale. Table 8.3b provides an overview of the developing characteristics in each stage.

Table 8.3b. Tanner Scale Stages[10]

| Stage | Male | Female | Pubic Hair (both males and females) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Stage 1 (prepubertal) | Testicular volume < 4 mL or long axis < 2.5 cm | No glandular breast tissue palpable | No hair |

| Stage 2 | 4 mL-8 mL (or 2.5 to 3.3 cm long) | Breast bud palpable under the areola | Downy hair |

| Stage 3 | 9 mL-12 mL (or 3.4 to 4.0 cm long) | Breast tissue palpable outside areola; no areolar development | Scant terminal hair |

| Stage 4 | 15-20 mL (or 4.1 to 4.5 cm long) | Areola elevated above the contour of the breast, forming a “double scoop” appearance | Terminal hair that fills the entire triangle overlying the pubic region |

| Stage 5 | > 20 mL (or > 4.5 cm long) | The areolar mound recedes into a single breast contour with areolar hyperpigmentation, papillae development, and nipple protrusion | Terminal hair that extends beyond the inguinal crease onto the thigh |

Sexuality

Sexuality is a component of human development and encompasses complex interactions among chromosomes, anatomy, hormones, psychology, interpersonal relationships, and cultural influences. Cultural values and beliefs affect an individual’s views on sexuality, contraception, and gender identity.[11] Culture is a set of beliefs, attitudes, and practices shared by a group of people or community that is accepted, followed, and passed down to other members of the group. Culture is more than a person’s nationality or ethnicity and threads its way through the development of one’s self-concept, sexuality, and spirituality.[12]

Adolescents and adults who are mature and healthy in their sexuality are able to do the following[13]:

- Take responsibility for one’s own behavior

- Practice effective decision-making

- Affirm that human development includes sexual development, which may or may not include reproduction or sexual experience

- Seek further information about sexuality and reproduction as needed and make informed choices about family options and relationships

- Interact with all genders in respectful and appropriate ways

- Affirm one’s own gender identity and sexual orientation and respect the gender identities and sexual orientations of others

- Appreciate one’s body and enjoy one’s sexuality throughout life, expressing one’s sexuality in ways that are congruent with one’s values

- Express love and intimacy in appropriate ways

- Develop and maintain meaningful relationships, avoiding exploitative or manipulative relationships

- Exhibit skills and communication that enhance personal relationships with family, peers, and romantic partners

Gender Identity and Sexual Orientation

Distinctions between gender, sexual orientation, and sexual behavior are critical concepts in adolescent health and are significantly influenced by one’s culture. Biological sex is assigned at birth based on anatomical characteristics and chromosomes that determine whether a person is born biologically male or female.

Gender identity, gender roles, and gender expression are psychological and cultural constructs referring to various aspects of maleness, femaleness, or another nonbinary designation.[14] Gender identity refers to an individual’s innate sense of being male, female, androgynous (i.e., of indeterminant sex), nonbinary (i.e., a blend of both genders or don’t identify with either gender), or a preference to reject gender designation. An individual’s gender identity is generally established during early childhood but may evolve across their life span. Gender expression refers to a person’s outward demonstration of gender in relation to societal norms, such as in style of dress, hairstyle, or other mannerisms.[15] Transgender refers to a person whose gender identity does not correspond with the gender assigned to them at birth.[16]

Gender roles are social constructs based on masculinity and femininity that embody cultural expectations, attitudes, behaviors, and personality traits based on biological sex. An individual’s gender identity and gender role are influenced during early childhood by parents and immediate family members defining how a person expresses themselves as members of their gender. As children become adolescents, their influences broaden with peer, media, and community norms of gender and sexuality impacting their individual value systems.[17]

Sexual orientation refers to an individual’s pattern of physical, emotional, and romantic arousal (including fantasies, activities, and behaviors) and the gender(s) of persons to whom an individual is physically or sexually attracted. Sexual orientation is on a continuum and is manifested in one’s self-identity and behaviors.[18] The acronym LGBTQIA+ stands for lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer or questioning, intersex, asexual, and others in reference to gender identity and sexual orientation. Transgender people may be sexually oriented toward men, women, both sexes, or neither sex.[19] Definitions related to LGBTQIA+ concepts are described in Table 8.3c.

Table 8.3c. Definitions of Concepts Related to LGBTQIA+

| Term | Definition |

|---|---|

| Lesbian | Women attracted to other women |

| Gay | People who are attracted to the same gender |

| Bisexual | People who acknowledge the potential to be attracted to people across genders, including their own, in various ways and times |

| Transgender or Trans | A person whose gender identity does not match the biological sex given at birth. Trans is considered more inclusive because it covers more than gender. They may or may not alter their bodies surgically or hormonally |

| Queer | Some use queer to describe their fluid identities. It should only be used by those who claim it to describe themselves because it has been used in a negative context at times |

| Questioning | Sometimes the Q in LGBTQIA+ refers to questioning for people who are exploring their sexual orientation, gender identity, or gender expression |

| Intersex | People whose sex characteristics are between the biological expression for male and female, not pertaining to gender. Sometimes, characteristics are evident at birth, but not always. They can be of any gender, sexual orientation, or romantic orientation |

| Asexual | A person who does not experience sexual attraction |

| + (Plus) | People who define their gender such as genderfluid, non-binary, or two-spirit |

| Cisgender | A person whose gender identity matches their biological sex assigned at birth |

| Transition | A person going through a social, legal, or medical process to affirm their gender identity through the use of hairstyle, clothing, pronouns, identification documents, medication, and/or surgery |

| Two-spirit | A term used only by American Indian/Alaska Native people who identify themselves as such to refer to non-binary gender, sexuality-related identities, roles, and contributions |

| Gender Non-conforming | A person’s expression of gender is different from what is culturally expected |

See Figure 8.18[20] for an image of participants in an LGBT rally in Dublin.

An individual’s assessment of their sexual orientation is termed sexual identity. Formation of sexual identity may be fluid with experimentation with same-gender sexual contacts as part of adolescent development. Approximately 5 to 10 percent of teens identify as lesbian, gay, or bisexual.[21]

LGBTQIA+ people may experience stigma related to their gender identity and sexual identity and encounter barriers to accessing health care. Recent data indicates lesbian, gay, and bisexual youth are at increased risk of being bullied, having suicidal thoughts, and using illicit drugs.[22]

Gender Dysphoria

When a person’s assigned biological gender differs from their gender identity, they experience feelings of unease about their incongruent maleness or femaleness referred to as gender dysphoria. For example, a biologic male with an innate sense of being female may describe himself as “a woman trapped in a man’s body.”[23] People who are transgender have a gender identity or gender expression that differs from the sex they were assigned at birth. See Figure 8.12[24] for an image of a person displaying a sign at a rally for transgender equality.

Gender dysphoria is a psychiatric diagnosis. According to the American Psychiatric Association’s diagnostic criteria, at least six of the following symptoms must be exhibited for at least six months and associated with distress or impaired functioning for a child to be diagnosed with gender dysphoria[25]:

- A strong desire to be of the other gender or an insistence they are another gender

- A strong preference for dressing in clothing stereotypical of the other gender

- A strong preference for playing with toys, games, or activities stereotypical of the other gender

- A strong rejection of the toys, games, and activities stereotypical of their assigned gender

- A strong preference for cross-gender roles when playing

- A strong preference for playmates of the other gender

- A strong dislike of one’s sexual anatomy

- A strong desire to have the primary and/or secondary sex characteristics of the other gender

Only a small percentage of children who display gender dysphoria will continue to show these characteristics into adolescence or adulthood. Adolescents with gender dysphoria who dread the appearance of secondary sexual characteristics may seek medical treatment like hormones or surgery to alter their masculine or feminine appearance.[26]

Asking clients about their preferred pronouns (i.e., he, she, they, ze) is considered part of a nursing assessment. By promoting sexuality as healthy, respectful, and meaningful in the global context of adolescent development, nurses can encourage a positive model of empowerment for youth exploring their gender and sexual identities.[27]

Adolescent Reproductive Health

Many adolescents engage in risky behaviors and experiences that can result in unintended poor health outcomes. The following statistics resulted from a survey among U.S. high school students in 2021[28]:

- 30% had experienced sexual intercourse

- 48% did not use a condom the last time they had sex

- 8% had been physically forced to have sexual intercourse when they did not want to

- 5% of all students had been tested for sexually transmitted infections during the past year

Sexual risky behaviors place youth at risk for sexually transmitted infection (STI), HIV infection, and unintended pregnancy. More than half of the nearly 20 million new STIs reported in 2020 were among adolescents aged 15–24; 20% of all new HIV diagnoses were among adolescents aged 13–24 in 2020; and more than 145,000 infants were born to adolescent females in 2021.[29]

State laws vary regarding consent for treating minors under age 18. As a general rule, a health care provider may not treat a minor without the consent of the minor’s parent or guardian, but there are often exceptions regarding treatment for STI, pregnancy, or for prescribing contraceptives. In some states, minors may receive confidential treatment without parental consent because they may not otherwise seek health care if they have to tell their parents. Privacy may also be an issue for minors when their parents receive an explanation of benefits form from their insurance company that describes the person who obtained care, the care provided, and the provider.[30] Nurses must be aware of the state laws regarding treatment for minors in the states in which they practice.

Read an issue brief from the Wisconsin Legislative Council on Health Care and Confidentiality of Records for Minors in the state of Wisconsin.

Along with school health programs, nurses can help adolescents adopt behaviors to reduce their risk for STI, HIV, and unintended pregnancy. According to the CDC, these health programs should incorporate the following[31]:

- Provide health information that is basic, accurate, and directly contributes to health-promoting decisions and behaviors.

- Address the needs of youth who are not having sex, as well as youth who are currently sexually active.

- Ensure that all youth are provided with effective education and skills to protect themselves and others from STI, HIV, and unintended pregnancy.

- Be consistent with community values.

Older Adults’ Reproductive Health

Men

As men age, male reproductive system changes may include changes in sperm production, the prostate gland, erectile function, and libido. These changes tend to gradually occur. The testes continue to produce sperm, but the rate of sperm cell production slows. The prostate gland enlarges in about 50% of men in a condition called benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH). BPH may cause problems with slowed urination and ejaculation. Age and prostate function do not predict male fertility. Older men can (and do) father children. Some men may have a lower sex drive (libido). Sexual responses may become slower and less intense. This may be due to a decreased testosterone level, chronic illness (such as diabetes or cardiovascular disease), psychological or social changes due to aging (such as the lack of a willing partner), or certain medications.[32]

Women

Changes in the female reproductive system due to aging are caused by decreased estrogen and progesterone levels. One clear sign of aging is menopause, when menstrual periods stop permanently, defined by no menstrual cycles for one year. Medical confirmation of menopause includes 12 months of no menstrual cycle and a FSH level of 30 mIU/mL or higher. Menopause typically occurs between the ages of 45 and 55, with the average age of 51. The time before menopause is called perimenopause, which can begin four to eight years before a woman’s last menstrual period. Signs of perimenopause are as follows[33]:

- Menstrual cycles are initially more frequent and may become irregular or longer or shorter in length

- Changes in the amount of menstrual flow

- Menstrual cycles eventually become less frequent until they stop completely

Along with changes in menstrual cycle, these physical changes in the body and reproductive tract also occur[34]:

- The vaginal walls become thinner, dryer, less elastic, and can become irritated. The external genital tissue decreases and thins and can also become irritated. Sometimes sex becomes painful due to these vaginal changes.

- The risk for vaginal yeast infections increases.

- Hot flashes, moodiness, headaches, and trouble sleeping can persist for years.

- Short-term memory can become impaired.

- Breast tissue decreases.

- Sex drive (libido) and sexual response decrease.

- Risk for osteoporosis increases.

- The urinary system changes, with frequency, urgency, and increased risk for urinary tract infection.

- The loss of muscle tone in the pelvic floor pubic muscles can result in the vagina, uterus, bladder, or colon falling out of position (referred to as prolapse). A cystocele, also known as a prolapsed bladder, occurs when the bladder bulges into the vaginal wall. A rectocele, also known as posterior vaginal prolapse, occurs when the rectum bulges into the vaginal wall. Surgery may be required to fix the prolapse.

Women experiencing perimenopause and menopause should be counseled to continue to use a birth control method until they have not had a menstrual cycle for 12 months. Any bleeding that occurs more than one year after their last period is not normal and should be evaluated by their health care provider.[37]

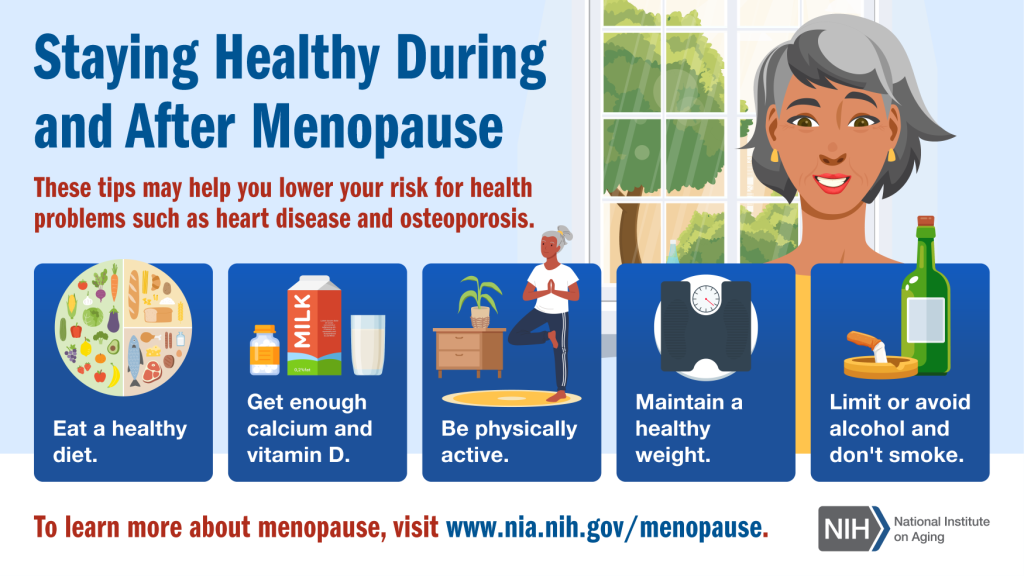

Menopausal symptoms can significantly affect a woman’s quality of life. Nurses can provide health teaching about common symptoms and treatments[38]:

- Mood changes: Menopause can cause women to feel moody and/or irritable. Some women may elect to try St John’s Wort or vitamin B6 dietary supplements. Nurses encourage clients to speak to their health care provider about their symptoms and possible treatments like antidepressants and counseling.

- Incontinence: Menopause may cause women to have sudden urges to urinate; leak urine during exercise, sneezing, or laughing; or develop urinary tract infections. Nurses can teach women to perform Kegel exercises to strengthen their pelvic floor and to speak to their health care provider about symptoms and treatments.

- Hot flashes (vasomotor instability): Many women have hot flashes, which can last for many years after menopause and are related to changing estrogen levels. A hot flash is a sudden feeling of heat in the upper part or all of the body. The face and neck may become flushed, and red blotches may appear on their chest, back, and arms. Most hot flashes last between 30 seconds and 10 minutes and can happen several times a day or a few times a week. Nurses can teach women to dress in layers that can be easily removed and replaced and to speak to their health care provider about symptoms and treatments.

- Night sweats: Women may experience hot flashes while sleeping, resulting in diaphoresis, commonly referred to as night sweats. Nurses can teach women to wear cool pajamas, keep a cold pack on their pillow or feet, use a fan, and sip cool water through the night. Some women may elect to try using black cohosh dietary supplements to manage night sweats, but research has demonstrated that it does not effectively treat vasomotor symptoms.[39]

- Trouble sleeping: Women may experience problems falling asleep, awakening too early, or awakening frequently throughout the night due to night sweats. Nurses can teach women good sleep hygiene, such as maintaining consistent sleep hours; using the bed only for sleep or sex; keeping the bedroom cool, quiet, and dark; avoiding screens; and avoiding alcohol, caffeine, and drinking liquids within two hours of sleep. Some women may find it helpful to ingest warm milk or peanuts or drink chamomile tea before bedtime due to their relaxing effects. Some women may try using lavender or melatonin supplements to help promote sleep, but research is inconclusive regarding their effectiveness.[40]

- Vaginal discomfort: After menopause, the vagina may become drier, which can make sexual intercourse uncomfortable. Nurses can teach women to use lubricants during sex to ease symptoms of vaginal atrophy or use a vaginal moisturizer. Women may speak with their health care provider about using estradiol topical vaginal cream for vaginal burning, itching, and dryness.

Nurses also provide general health teaching to women about staying healthy during menopause. See Figure 8.13[41] for an infographic regarding general health teaching.

Hormone Replacement Therapy

Hormone replacement therapy (HRT) refers to estrogen and progesterone replacement therapy to decrease moderate to severe vasomotor and vaginal symptoms for women in menopause when their ovaries decrease production of these hormones. HRT also helps prevent osteoporosis. However, research demonstrates that HRT can have adverse health risks to women over 60, such as breast cancer, cardiovascular disease, venous thromboembolism, and stroke. HRT may be prescribed to women younger than age 60 to help manage menopausal symptoms. Nurses teach women to speak with their health care providers about the benefits and risks of HRT.[42] Read additional information about hormone replacement therapy in the “Perimenopause and Menopause” section of the “Reproductive System Alterations” chapter.

- “Figure_28_03_01.jpg” by OpenStax College is licensed under CC BY 3.0 ↵

- Dooley, L., Chruścik, A., Kauter, K., Windus, L., & Whiteside, E. (2021). Fundamentals of anatomy and physiology. University of Southern Queensland. https://usq.pressbooks.pub/anatomy/ ↵

- Dooley, L., Chruścik, A., Kauter, K., Windus, L., & Whiteside, E. (2021). Fundamentals of anatomy and physiology. University of Southern Queensland. https://usq.pressbooks.pub/anatomy/ ↵

- Dooley, L., Chruścik, A., Kauter, K., Windus, L., & Whiteside, E. (2021). Fundamentals of anatomy and physiology. University of Southern Queensland. https://usq.pressbooks.pub/anatomy/ ↵

- Dooley, L., Chruścik, A., Kauter, K., Windus, L., & Whiteside, E. (2021). Fundamentals of anatomy and physiology. University of Southern Queensland. https://usq.pressbooks.pub/anatomy/ ↵

- Dooley, L., Chruścik, A., Kauter, K., Windus, L., & Whiteside, E. (2021). Fundamentals of anatomy and physiology. University of Southern Queensland. https://usq.pressbooks.pub/anatomy/ ↵

- Feng, C. C., Agostini, M., & Bertiz, R. (n.d.). Health assessment guide for nurses. Montgomery College. https://pressbooks.montgomerycollege.edu/healthassessment/ ↵

- Dooley, L., Chruścik, A., Kauter, K., Windus, L., & Whiteside, E. (2021). Fundamentals of anatomy and physiology. University of Southern Queensland. https://usq.pressbooks.pub/anatomy/ ↵

- “Tanner_scale_male_intact” and “Tanner_scale-female” by M. Komorniczak is licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0 ↵

- Emmanuel, M., & Bokor, B. R. (2022). Tanner stages. StatPearls [Internet]. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK470280/ ↵

- Forcier, M. (2023). Sexual development and sexuality in children and adolescents. UpToDate. https://www.uptodate.com ↵

- Ernstmeyer, K., & Christman, E. (Eds.). (2024). Nursing fundamentals (2nd ed.). WisTech Open. https://wtcs.pressbooks.pub/nursingfundamentals/ ↵

- Forcier, M. (2023). Sexual development and sexuality in children and adolescents. UpToDate. https://www.uptodate.com ↵

- Forcier, M. (2023). Sexual development and sexuality in children and adolescents. UpToDate. https://www.uptodate.com ↵

- Keuroghlian, A. S., Ard, K. L., & Makadon, H. J. (2017). Advancing health equity for lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender (LGBT) people through sexual health education and LGBT-affirming health care environments. Sexual Health, 14(1), 119–122. https://doi.org/10.1071/SH16145 ↵

- Ernstmeyer, K., & Christman, E. (Eds.). (2024). Nursing fundamentals (2nd ed.). WisTech Open. https://wtcs.pressbooks.pub/nursingfundamentals/ ↵

- Forcier, M. (2023). Sexual development and sexuality in children and adolescents. UpToDate. https://www.uptodate.com ↵

- Forcier, M. (2023). Sexual development and sexuality in children and adolescents. UpToDate. https://www.uptodate.com ↵

- Meerwijk, E. L., & Sevelius, J. M. (2017). Transgender population size in the United States: A meta-regression of population-based probability samples. American Journal of Public Health, 107(2), e1–e8. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2016.303578 ↵

- “Dublin_LGBTQ_Pride_Festival_2013_-_LGBT_Rights_Matter_(9183564890).jpg” by infomatique is licensed under CC BY-SA 2.0 ↵

- Forcier, M. (2023). Sexual development and sexuality in children and adolescents. UpToDate. https://www.uptodate.com ↵

- Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion. (n.d.). Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender health workgroup. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. https://health.gov/healthypeople/about/workgroups/lesbian-gay-bisexual-and-transgender-health-workgroup ↵

- Forcier, M. (2023). Sexual development and sexuality in children and adolescents. UpToDate. https://www.uptodate.com ↵

- “2013_Rally_for_Transgender_Equality_21175.jpg” by Ted Eytan is licensed under CC BY-SA 2.0 ↵

- American Psychiatric Association. (2022). Desk reference to the diagnostic criteria from DSM-5-TR. American Psychiatric Association Inc. ↵

- Forcier, M. (2023). Sexual development and sexuality in children and adolescents. UpToDate. https://www.uptodate.com ↵

- Forcier, M. (2023). Sexual development and sexuality in children and adolescents. UpToDate. https://www.uptodate.com ↵

- Feng, C. C., Agostini, M., & Bertiz, R. (n.d.). Health assessment guide for nurses. Montgomery College. https://pressbooks.montgomerycollege.edu/healthassessment/ ↵

- Feng, C. C., Agostini, M., & Bertiz, R. (n.d.). Health assessment guide for nurses. Montgomery College. https://pressbooks.montgomerycollege.edu/healthassessment/ ↵

- Levine, J., Gold, R. B., Nach, E., & English, A. (2012). Confidentiality for individuals insured as dependents: A review of state laws and policies. Guttmacher Institute. https://www.guttmacher.org/report/confidentiality-individuals-insured-dependents-review-state-laws-and-policies ↵

- Feng, C. C., Agostini, M., & Bertiz, R. (n.d.). Health assessment guide for nurses. Montgomery College. https://pressbooks.montgomerycollege.edu/healthassessment/ ↵

- MedlinePlus [Internet]. (2022). Aging changes in the male reproductive system. https://medlineplus.gov/ency/article/004017.htm ↵

- MedlinePlus [Internet]. (2022). Aging changes in the female reproductive system. https://medlineplus.gov/ency/article/004016.htm ↵

- MedlinePlus [Internet]. (2022). Aging changes in the female reproductive system. https://medlineplus.gov/ency/article/004016.htm ↵

- Premier Health. (2016, May 9). Cystocele [Video]. YouTube. All rights reserved. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=rEDyx6fWC3U ↵

- Premier Health. (2016, May 9). Rectocele [Video]. YouTube. All rights reserved. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=UfhyUrhluVk ↵

- MedlinePlus [Internet]. (2022). Aging changes in the female reproductive system. https://medlineplus.gov/ency/article/004016.htm ↵

- National Institute on Aging. (n.d.). Menopause. https://www.nia.nih.gov/health/menopause ↵

- National Institutes of Health. Office of Dietary Supplements. (n.d.). Health information: Dietary supplement fact sheets. https://ods.od.nih.gov/factsheets/list-all/#L ↵

- National Institutes of Health. Office of Dietary Supplements. (n.d.). Health information: Dietary supplement fact sheets. https://ods.od.nih.gov/factsheets/list-all/#L ↵

- “nia-menopause-infographic” by National Institute on Aging is in the Public Domain. ↵

- Harper-Harrison, G., Carlson, K., & Shanahan, M. M. (2024). Hormone replacement therapy. StatPearls [Internet]. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK493191/ ↵

The phase of development during which individuals undergo physical changes that lead to sexual maturity and reproductive capability.

Physical traits that develop during puberty, such as breast development in females or facial hair in males, that are not directly involved in reproduction.

The components of the reproductive system that produce gametes.

Characteristics that are present at birth, such as ovaries in females and testes in males.

The first occurrence of menstruation in a female, marking the beginning of reproductive capability.

A scale that measures the physical development of children, adolescents, and adults based on external primary and secondary sex characteristics.

The classification of individuals based on physical and genetic characteristics such as chromosomes, hormone levels, and reproductive/sexual anatomy.

An individual's personal sense of their own gender, which may or may not correspond with the sex they were assigned at birth.

The external presentation of one's gender identity, which can include behavior, clothing, haircut, voice, and other forms of presentation.

A term describing individuals whose gender identity differs from the sex they were assigned at birth.

Societal norms and expectations regarding behaviors, activities, and attributes considered appropriate for men and women.

A person’s enduring emotional, romantic, or sexual attraction to others, which can include being heterosexual, homosexual, bisexual, or others.

An inclusive acronym that stands for Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, Queer or Questioning, Intersex, Asexual, and other sexual orientations and gender identities.

Distress or discomfort that occurs when an individual’s gender identity does not align with their sex assigned at birth.

The natural cessation of menstrual periods for 12 consecutive months, marking the end of a woman's reproductive years.

The transitional period leading up to menopause, characterized by hormonal fluctuations and changes in menstrual cycles.

A condition where the bladder bulges into the vagina, often due to weakened pelvic muscles, which can lead to urinary incontinence.

A condition in which the rectum bulges into the vaginal wall due to weakened pelvic muscles.