7.6 Psychotropic Medications

This section will provide an overview of common classes of psychotropic medications used to treat mental health conditions that are discussed in this chapter.

Information about medications changes frequently, so it is vital for nurses to consult evidence-based resources for the latest drug information, warnings, and client education guidelines when administering medications. Free reference information is provided by the National Library of Medicine (NLM) on the DailyMed website. DailyMed is a database containing current information from the Food and Drug Administration on prescription and over-the-counter medications. It provides essential information to health professionals for the safe and effective use of medications, including indications, dosage and administration, contraindications, boxed warnings and precautions, adverse reactions, drug interactions, information about use in specific populations, and other important information for health care practitioners.[1] Specific information about psychotropic medications can also be found on the National Alliance on Mental Illness’ Mental Health Medications web page.

Visit the DailyMed web page for current information about prescription medications.

Visit the National Alliance on Mental Illness’ Mental Health Medications web page.

Clients who are pregnant or breastfeeding should weigh risks and benefits of psychotropic drugs on their health and the health of their babies. Some clients may delay treatment due to concerns about the effects of medications; however, they should also weigh the risk of untreated mental health conditions on their welfare. Nurses can use resources in the following box to help clients investigate the effects of medications for their situations.

Visit the MGH Center for Women’s Mental Health website for additional information about “Breastfeeding and Psychiatric Medications” and “Psychiatric Disorders During Pregnancy.”

Neurotransmitters

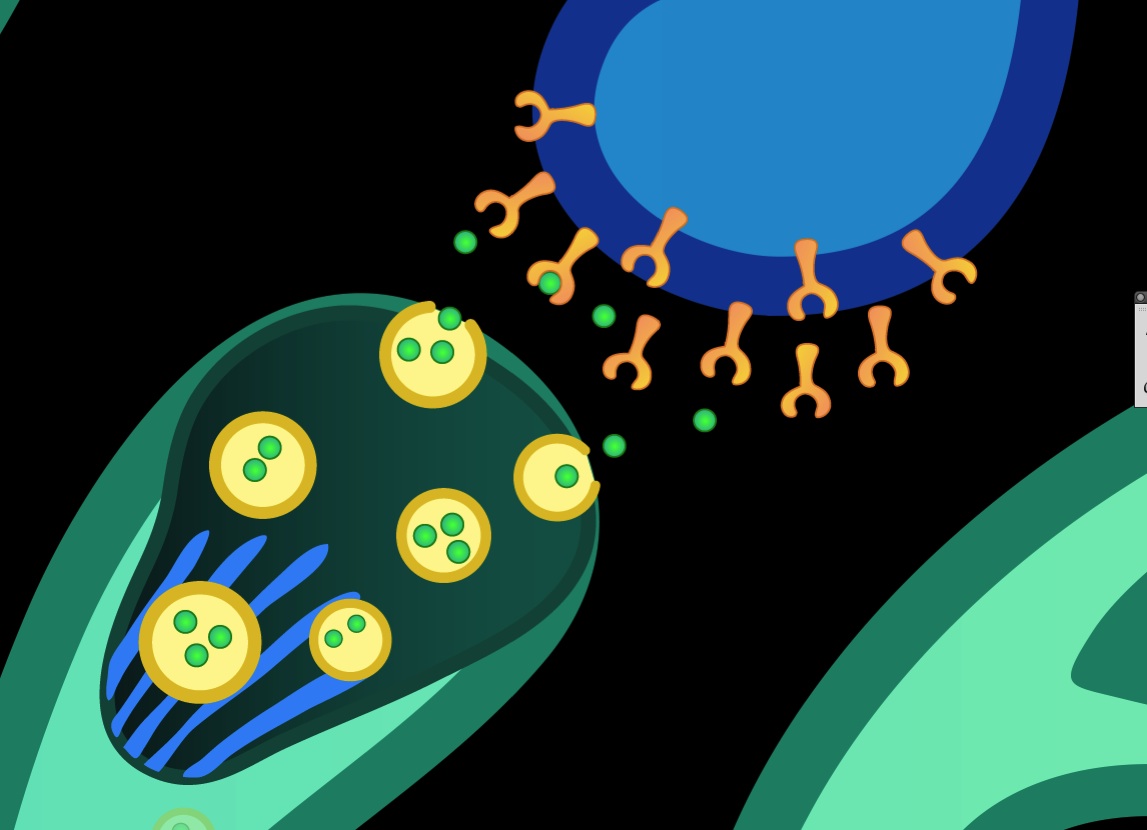

As described in the “Mental Health Concepts” chapter, neurotransmitters are chemical substances released at the end of a neuron by the arrival of an electrical impulse. They diffuse across the synapse and cause the transfer of the impulse to another nerve fiber, a muscle fiber, or other structure. Neurotransmitters interact with specific receptors like a key and a lock. Understanding neurotransmission helps nurses be knowledgeable of mental health conditions and their associated medications. See Figure 7.4[2] for an illustration of neurotransmitters and receptors.

Complete a supplemental learning activity called “Psychotropic Medications and Neurotransmitters” from the Wisconsin Technical College System to view animations demonstrating neurotransmission, psychotropic medications, reuptake, and reuptake inhibition.

Types of Neurotransmitters

Several types of neurotransmitters are associated with mental health conditions and psychotropic medications[3],[4]:

- Serotonin: Serotonin modulates multiple neuropsychological processes such as mood, sleep, libido, and temperature regulation. Abnormal levels of serotonin have been linked to many mental health disorders such as depression, bipolar disorder, and anxiety. Many psychotropic medications target serotonin. For example, fluoxetine belongs to a class of antidepressants called selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs). SSRIs prevent the reuptake of serotonin at the synapse, making more of the chemical available in the brain and relieving depression.

- Norepinephrine and Epinephrine: Norepinephrine and epinephrine stimulate alpha- and beta-receptors in the sympathetic nervous system. Their release exerts effects on a variety of body processes, including stress, sleep, attention, and focus. Many psychotropic medications target these neurotransmitters. For example, venlafaxine belongs to a class of antidepressants called norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (NRIs). NRIs are prescribed to treat depression by preventing the reuptake of norepinephrine at the synapse and boosting levels of norepinephrine in the brain.

- Gamma-Aminobutyric Acid (GABA) and Glycine: GABA and glycine are inhibitory neurotransmitters that act like brakes in a car by slowing down overexcited nerve cells. Low levels of GABA are associated with seizures, anxiety, mania, and impulse control. Pregabalin is an anticonvulsant that mimics the effects of GABA and is used to treat generalized anxiety disorder.

- Glutamate: Glutamate is an excitatory neurotransmitter. Elevated levels of glutamate are associated with psychosis symptoms that can occur with schizophrenia, as well as with illicit drug use such as methamphetamines. Conversely, lamotrigine, a medication used to treat bipolar disorder, inhibits glutamate.

- Dopamine: Dopamine plays an essential role in several brain functions, including learning, motor control, reward, emotion, and executive functions. It is associated with several mental health disorders and is targeted by many psychotropic medications. For example, bupropion is an antidepressant that inhibits dopamine reuptake, leading to increased dopamine levels in the synapse and relieving the symptoms of depression. Conversely, chlorpromazine blocks dopamine receptors and is used to treat psychosis, but this blockade can cause extrapyramidal side effects (involuntary and uncontrolled muscle movements).

- Histamine: Histamine mediates homeostatic functions in the body, promotes wakefulness, modulates feeding behavior, and controls motivational behavior. For example, diphenhydramine, a histamine antagonist, causes drowsiness and is also used to treat extrapyramidal symptoms.

- Acetylcholine: Acetylcholine stimulates nicotinic and muscarinic receptors in the parasympathetic nervous system. Other substances also bind to these receptors. For instance, nicotine (in tobacco products) binds to nicotinic receptors, and muscarine (products of specific mushrooms used as a hallucinogenic) binds to muscarinic receptors.

The following subsections will describe common classes of medications used to treat mental health conditions that impact many of these neurotransmitters.

Antidepressants

Antidepressants are commonly used to treat depression but are also used to treat other mental health conditions, such as anxiety, bipolar disorder, and insomnia.

Several classes and types of antidepressants exist, including selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), serotonin and norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs), norepinephrine and dopamine reuptake inhibitors (NDRIs), serotonin antagonist and reuptake inhibitors, tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs), and monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAOIs). TCAs and MAOIs are often referred to as first-generation antidepressants because they were first marketed in the 1950s. They have many side effects and are not prescribed as frequently to treat depression as SSRIs, SNRIs, and NDRIs, which have fewer side effects.

Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitors

Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) prevent the reuptake of serotonin at the synapse, causing the serotonin neurotransmitter to stay in the synapse longer, thereby raising the level of serotonin in the brain. SSRIs are primarily used to treat depression and are also used to treat bipolar disorder, obsessive-compulsive disorder, bulimia, panic disorder, post-traumatic stress disorder, anxiety, premenstrual syndrome, and migraines. Examples of common SSRIs include fluoxetine, citalopram, sertraline, paroxetine, and escitalopram.

Serotonin Norepinephrine Reuptake Inhibitors

Serotonin norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs) prevent the reuptake of serotonin and norepinephrine, with weak inhibition of dopamine reuptake. Examples of SNRIs are venlafaxine and duloxetine.

Norepinephrine and Dopamine Reuptake Inhibitors

Norepinephrine and dopamine reuptake inhibitors (NDRIs) work by directly blocking norepinephrine and dopamine receptors in the brain, thereby increasing active circulating norepinephrine and dopamine. NDRIs do not have an effect on serotonin levels. Bupropion is an example of an NDRI. It is used to treat depressive, seasonal affective, and attention deficit disorders and to help people stop smoking.

Serotonin Antagonist and Reuptake Inhibitor

Trazodone is an example of a serotonin antagonist and reuptake inhibitor. It is an antidepressant but is prescribed off-label for anxiety or as a hypnotic. Trazodone reduces levels of the neurotransmitters associated with arousal effects, such as serotonin, noradrenaline, dopamine, acetylcholine, and histamine. Low-dose trazodone use exerts a sedative effect for sleep, so is typically administered in the evening.

Tricyclic Antidepressants

Tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs) are older first-generation antidepressants that block the reuptake of serotonin and norepinephrine in the synapse, which leads to increased concentration of these neurotransmitters in the brain. They are now more commonly prescribed to treat neuropathic pain and insomnia. An example of a TCA is amitriptyline.

TCAs are often administered at bedtime due to sedating effects. Older adults are particularly sensitive to the anticholinergic side effects (e.g., tachycardia, urinary retention, constipation, dry mouth, blurred vision, confusion, psychomotor slowing, sedation, and delirium) of tricyclic antidepressants. Elderly clients should be started on low doses of amitriptyline and observed closely because they are at increased risk for falls. Blockage of adrenergic receptors can cause cardiac conduction disturbances and hypotension. Death may occur from overdosage with this class of drugs.

If overdose occurs, call 911 in an outpatient setting or rapid response in an inpatient setting. Responders can consult with a Certified Poison Control Center (1-800-222-1222) or go to https://www.poisonhelp.org/help for the latest treatment recommendations.

Monoamine Oxidase Inhibitors

Monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAOIs) are an older first-generation antidepressant. MAOIs are contraindicated with all other classes of antidepressants. Monoamine oxidase is an enzyme that removes the neurotransmitters norepinephrine, serotonin, and dopamine from the brain. By inhibiting the monoamine oxidase enzyme, norepinephrine, serotonin, and dopamine levels available in the brain will increase. Tranylcypromine is an example of an MAOI.

A significant disadvantage to MAOIs is their potential to cause a hypertensive crisis when taken with stimulant medications or foods or beverages containing tyramine. Hypertensive crisis is a medical emergency defined as severe hypertension (blood pressure over 180/120 mm Hg) with acute end-organ damage such as stroke, myocardial infarction, or acute kidney damage. Examples of foods containing tyramine are aged cheese, cured or smoked meats, alcoholic beverages, and soy sauce. Older adults are at increased risk for postural hypotension and serious adverse effects.

Classes of antidepressants and their mechanisms of action are outlined in Table 7.6a.

Table 7.6a. Antidepressants

| Medication Class | Mechanism of Action |

|---|---|

| Serotonin-Norepinephrine Reuptake Inhibitors (SNRIs)

Common examples: Venlafaxine Duloxetine |

Block the uptake of both serotonin and norepinephrine from the cell synapse. Similar to SSRIs but with two neurotransmitters. |

| Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitors (SSRIs)

Common examples: Fluoxetine Sertraline Citalopram |

Impact the receptors of the cell synapse to inhibit or prevent the uptake of serotonin, making the neurotransmitter serotonin stay in the synapse longer. |

| Tricyclic Antidepressants (TCAs)

Common examples: Amitriptyline Nortriptyline |

Block the presynaptic receptor for norepinephrine and partially serotonin. This makes the neurotransmitter norepinephrine level increase in the synapse. |

| Monoamine Oxidase Inhibitors (MAOIs)

Common examples: Phenelzine Tranylcypromine |

Block the enzyme that breaks down monoamine, which causes an increase in the level of neurotransmitters serotonin and norepinephrine. |

| Norepinephrine and Dopamine Reuptake Inhibitor (NDRI)

Example: Bupropion |

Block the uptake of both norepinephrine and dopamine from the cell synapse. |

| Serotonin Antagonist and Reuptake Inhibitor

Example: Trazodone |

Reduces levels of the neurotransmitters associated with arousal effects, such as serotonin, noradrenaline, dopamine, acetylcholine, and histamine. |

Side Effects

Common side effects of frequently prescribed SSRIs and SNRIs are as follows:

- Feeling agitated, shaky or anxious

- Gastrointestinal upset, diarrhea, constipation, loss of appetite, thirst, dry mouth

- Dizziness

- Insomnia or feeling very sleepy

- Headaches

- Loss of libido (reduced sex drive), difficulties achieving orgasm, or difficulties obtaining or maintaining an erection

Side effects generally improve within a few weeks, although some can occasionally persist and require tapering or switching to a different class of antidepressant. In rare cases, some people experience suicidal ideation or a desire to self-harm when they first begin taking antidepressants. Young people under 25 are particularly at risk.

Read additional information about side effects of antidepressant medications in the “Treatments for Depression” section of the “Depressive Disorders” chapter of Open RN Nursing: Mental Health & Community Concepts.

Serotonin Syndrome

High doses of antidepressants or a combination of medications that affect serotonin, such as antidepressants or triptans (used to treat migraine headaches), can cause a medical emergency called serotonin syndrome. The presentation of serotonin syndrome is extremely variable, ranging from mild symptoms to a life-threatening syndrome. It typically develops within 24 hours from the increased dosage or combination of medications and can be fatal. Nurses must recognize signs of serotonin syndrome in clients at risk and promptly report concerns to the health care provider. Symptoms of serotonin syndrome can be classified into three categories:

- Mental status changes: Agitation, restlessness, or delirium

- Autonomic hyperactivity: Tachycardia, hypertension, hyperthermia, diaphoresis, shivering, vomiting, or diarrhea

- Neuromuscular hyperactivity: Tremor, muscle hypertonia or rigidity, myoclonus (sudden, brief, involuntary muscle twitches or jerking that can’t be controlled by the person experiencing it), hyperreflexia, or clonus (including rapid, horizontal eye movements)

People with serotonin syndrome can become severely ill if not quickly treated in the hospital. Untreated, serotonin syndrome can be deadly. With treatment, symptoms usually go away within 24 hours, but muscle breakdown and permanent kidney damage may result. Treatment includes stopping all medications that increase serotonin levels, as well as intravenous fluids to flush the byproducts of muscle damage through the kidneys.

General Health Teaching About Antidepressants

Antidepressants may produce some improvement within the first week or two, but full benefits may not be seen for two to three months. If a client feels little or no improvement after several weeks, the provider can alter the dose of the medication, add another medication, or substitute another antidepressant. In a similar manner, if a client develops ongoing bothersome side effects, the provider can switch them to a different medication. Nurses should encourage clients to contact their mental health care provider if a medication is not working within the expected time frame or if they are experiencing ongoing bothersome side effects. A typical recommendation is for clients to continue medication(s) for six or more months after the symptoms have improved. Long-term maintenance therapy may be suggested to decrease the risk of future episodes for people at high risk for recurrence.

Clients should be instructed to not suddenly stop taking antidepressants or they may experience withdrawal symptoms. When it is time to stop the medication, the provider will slowly and safely decrease the dose. If clients stop taking the medication before the provider advises, the depression may return. Clients should also be counseled that if they do not feel better with the first antidepressant prescribed, the provider may need to try several different classes of medications to find one that works best for them.

Review additional information in the “Antidepressants” section of the “Central Nervous System” chapter of Open RN Nursing Pharmacology, 2e.

Mood Stabilizer – Lithium

The most commonly prescribed mood stabilizer is lithium. Lithium is primarily used to treat mania in bipolar disorder. Lithium reduces excitatory neurotransmission (dopamine and glutamate) and increases inhibitory neurotransmission (GABA). It also alters sodium transport in nerve and muscle cells and causes a shift in metabolism of catecholamines. When administered to a client experiencing a manic episode, lithium may reduce symptoms within one to three weeks. It also possesses unique antisuicidal properties that sets it apart from antidepressants.

Side Effects

Lithium toxicity can occur at doses close to therapeutic levels, so lithium levels must be routinely monitored regularly. Signs of lithium toxicity must be promptly reported to the health care provider for dosage adjustment and treatment. Lithium blocks ADH, so symptoms of diabetes insipidus (i.e., excessive thirst and urination) should be monitored and promptly reported. Lithium’s mechanism of action, nursing considerations, and side effects are summarized in Table 7.6b.

Table 7.6b. Lithium

| Medication Class | Nursing Considerations | Common Side Effects

(*Indicates medical emergency) |

|---|---|---|

| Lithium |

|

Lithium blocks ADH, so monitor for symptoms of diabetes insipidus (i.e., excessive thirst and urination)

*Lithium toxicity (notify the health care provider)

*Lithium levels > 2.5 mEq/L constitute a medical emergency, even if the client is asymptomatic.

|

Health Teaching About Lithium

Nurses teach clients that lithium must be taken as prescribed or serious side effects can occur. They reinforce the importance of adhering to regular blood tests to measure lithium levels and reporting symptoms of elevated levels of lithium, including diarrhea, vomiting, drowsiness, muscular weakness, lack of coordination, ringing in the ears (tinnitus), or large amounts of dilute urine. Driving or operating heavy machinery should be avoided when first starting lithium because it can impair mental alertness. Lithium should not be taken during pregnancy or while breastfeeding unless it is determined that the benefits to the mother outweigh the potential risks to the baby.

Read additional information about lithium in the “Antimanias” section of the “Central Nervous System” chapter of Open RN Nursing Pharmacology, 2e.

Antianxiety Medications

Antianxiety medications help reduce the symptoms of anxiety, panic attacks, or extreme fear and worry. The most common class of antianxiety medications is benzodiazepines. Benzodiazepines are used to treat generalized anxiety disorder, although SSRIs or other antidepressants are typically used to treat panic disorder or social phobia (i.e., social anxiety disorder). Buspirone and beta-blockers and may also be prescribed for anxiety.

Benzodiazepines

Benzodiazepines are used to treat anxiety and are also used for their sedation and anticonvulsant effects because they bind to GABA receptors and stimulate the effects of GABA (an inhibitory neurotransmitter). Benzodiazepines include clonazepam, alprazolam, and lorazepam. Benzodiazepines are a controlled substance because they have a potential for misuse and can cause dependence. Short-acting benzodiazepines (such as lorazepam) and beta-blockers are used to treat the short-term symptoms of anxiety. Lorazepam is available for oral, intramuscular, or intravenous routes of administration.

Side Effects

Overdosage of benzodiazepines causes central nervous system depression, ranging from drowsiness to coma. Children and older adults are more susceptible to the sedative and respiratory depressive effects of lorazepam and may experience paradoxical reactions such as tremors, agitation, or visual hallucinations. Benzodiazepines may cause fetal harm when administered to pregnant women. There is a boxed warning that concomitant use of benzodiazepines and opioids may result in profound sedation, respiratory depression, coma, and death. See Table 7.6c for summarized information about benzodiazepines.

Table 7.6c. Benzodiazepines

| Generic | Nursing Considerations | Side/Adverse Effects |

|---|---|---|

|

May cause fetal harm in pregnant women and may cause paradoxical effect in children | Boxed Warning: Concomitant use of benzodiazepines and opioids may result in profound sedation, respiratory depression, coma, and death

Increased risk for falls |

Health Teaching

Clients should be cautioned that driving a motor vehicle, operating machinery, or engaging in hazardous or other activities requiring attention and coordination should be delayed for 24 to 48 hours following administration of benzodiazepines or until the effects of the drug, such as drowsiness, have subsided. Alcoholic beverages should not be consumed for at least 24 to 48 hours after receiving lorazepam due to the additive effects on central nervous system depression. Hospitalized clients should be advised that benzodiazepines increase fall risk, and getting out of bed unassisted may result in falling and potential injury

Buspirone

Buspirone is a non-benzodiazepine medication indicated for the treatment of chronic anxiety. It is included in the class of medications called anxiolytics, but it is not chemically related to benzodiazepines, barbiturates, or other sedatives. Buspirone should not be taken concurrently with a monoamine oxidase inhibitor (MAOI) due to the risk of fatal side effects. It can also cause serotonin syndrome if used in combination with MAOIs, SSRIs, or SNRIs.

Buspirone increases serotonin and dopamine levels in the brain. In contrast to benzodiazepines, buspirone must be taken every day for a few weeks to reach its full effect; it is not useful on an “as-needed” basis. A common side effect of buspirone is dizziness.

Beta-Blockers

Beta-blockers (such as propranolol) block sympathetic nervous system stimulation of Beta-1 receptors. They may be prescribed to manage the physical symptoms of anxiety (such as trembling, rapid heartbeat, and sweating) for a short period of time or used “as needed” to reduce acute physical symptoms.

Read more information about benzodiazepines in the “CNS Depressants” chapter and more information about propranolol in the “Beta-2 Antagonists” section of the “Autonomic Nervous System” chapter of Open RN Nursing Pharmacology, 2e.

Antipsychotics

Antipsychotic medications are primarily used to manage psychosis (i.e., a loss of contact with reality that may include delusions or hallucinations) caused by severe mental illness such as schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, or severe depression. Antipsychotic medications may also be used in combination with other medications to treat the symptoms of other mental health conditions, including attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), eating disorders, post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD), and generalized anxiety disorder.

There are two major classes of antipsychotics called first-generation antipsychotics (also called typical antipsychotics) and second-generation antipsychotics (also referred to as atypical antipsychotics). Clients respond differently to antipsychotic medications, so it may take several trials of different medications to find the one that works best for their symptoms.

First-Generation Antipsychotics

Common first-generation antipsychotic medications (also called “typical” antipsychotics) include chlorpromazine, haloperidol, perphenazine, and fluphenazine. First-generation antipsychotics have several potential adverse effects, and medication is prescribed based on the client’s ability to tolerate the adverse effects. First-generation antipsychotics work by blocking dopamine receptors in certain areas of the CNS associated with emotions, cognitive function, and motor function. As a result, blockage produces a tranquilizing effect in psychotic clients. However, several adverse effects can be caused by this dopamine blockade.

Side Effects

Common side effects of both first- and second-generation antipsychotics include the following[5]:

- Anticholinergic symptoms: dry mouth, constipation, blurred vision, or urinary retention

- Drowsiness

- Dizziness

- Restlessness

- Weight gain

- Nausea or vomiting

- Low blood pressure

First-generation antipsychotics, also known as neuroleptics or typical antipsychotics, have significant potential to cause extrapyramidal side effects and tardive dyskinesia due to their tight binding to dopamine receptors. Extrapyramidal side effects include tremors and slowed, involuntary, or uncontrollable movements or muscle contractions called dystonia. Dystonia refers to involuntary contractions of muscles of the extremities, face, neck, abdomen, pelvis, or larynx in sustained or intermittent patterns that lead to abnormal movements or postures. Tardive dyskinesia is a syndrome of movement disorders that persists for at least one month and can last up to several years despite discontinuation of the medications.

Neuroleptic malignant syndrome (NMS) is a rare but fatal adverse effect that can occur at any time during treatment with first- or second-generation antipsychotics. It typically develops over a period of days to weeks and resolves in approximately nine days with treatment. Signs include increased temperature, severe muscular rigidity, confusion, agitation, hyperreflexia, elevation in white blood cell count, elevated creatinine phosphokinase, elevated liver enzymes, myoglobinuria, and acute renal failure. The antipsychotic should be immediately discontinued if signs occur and the health care provider immediately notified for prompt treatment.

Second-Generation Antipsychotics

Second-generation antipsychotics (also called atypical antipsychotics) have fewer adverse effects and are generally better tolerated. Second-generation medications include risperidone, olanzapine, quetiapine, ziprasidone, aripiprazole, paliperidone, and lurasidone. Second-generation antipsychotics work by blocking specific D2 dopamine receptors and serotonin receptors. Several atypical antipsychotics have a “broader spectrum” of action than the older medications and are used for treating bipolar depression or depression that has not responded to an antidepressant medication alone.

Side Effects

Second-generation antipsychotics have a significantly decreased risk of extrapyramidal side effects but are associated with weight gain and the development of metabolic syndrome. Metabolic syndrome increases the risk of heart disease, stroke, and type 2 diabetes. Clinical symptoms of metabolic syndrome include high blood glucose, symptoms of diabetes (i.e., increased thirst and urination, fatigue, and blurred vision), obesity with a large abdominal girth, hypertension, elevated triglycerides, and lower levels of HDL.

Clozapine

Clients with treatment-resistant schizophrenia may be prescribed clozapine, a specific atypical antipsychotic medication that binds to serotonin, as well as dopamine receptors. Clozapine has strong anticholinergic, sedative, cardiac, and hypotensive properties and frequent drug-drug interactions. People treated with clozapine must undergo routine blood testing to detect a potentially dangerous side effect called agranulocytosis (extremely low white blood cell count).

Health Teaching About Antipsychotics

Clients should be advised to contact their provider if involuntary or uncontrollable movements occur. They should also be warned to not suddenly stop taking the medication because abrupt withdrawal can cause dizziness; nausea and vomiting; and uncontrolled movements of the mouth, tongue, or jaw. Furthermore, clients should be warned to not consume alcohol or other CNS depressants because their ability to operate machinery or drive may be impaired.

See Table 7.6d for an overview of first- and second-generation antipsychotics.

Table 7.6d. Antipsychotics

| Class | Generic | Side/Adverse Effects |

|---|---|---|

|

|

|

Read more information about antipsychotic medications in the “Antipsychotics” section of the “Central Nervous System” chapter in Open RN Nursing Pharmacology, 2e.

Stimulants

Stimulant medications are prescribed to treat children, adolescents, or adults diagnosed with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). Stimulants block the reuptake of norepinephrine and dopamine in the synapse and increase the overall level of these substances in the brain, but they have a paradoxical calming effect and improve the ability to focus and concentrate for individuals diagnosed with ADHD. Common stimulants used to treat ADHD include methylphenidate, amphetamine, dextroamphetamine, and lisdexamfetamine dimesylate.

Stimulant medications are safe when prescribed with close supervision, but they are a Schedule II controlled substance because they have a high potential for misuse and dependence. The risk of substance use disorder by the client, or their family members, should be assessed prior to prescribing stimulants, and signs of misuse and physical dependence should be evaluated while the client is receiving therapy. Nurses must be aware of the possibility of drug diversion or misuse of stimulants by adolescents or their caregivers. Up to 29 percent of school- and college-aged students with stimulant prescriptions have been asked to give, sell, or trade their medication.

Side Effects

Stimulants may cause minor side effects that resolve when the dosage is decreased, or a different stimulant is prescribed. The most common side effects include difficulty falling asleep or staying asleep, loss of appetite and weight loss, stomach pain, and headache. Less common side effects include motor or verbal tics (sudden, repetitive movements or sounds) or personality changes (such as appearing “flat” or without emotion). Sudden death, stroke, and myocardial infarction have been reported in children, adolescents, and adults with CNS-stimulant treatment at recommended doses. If paradoxical worsening of symptoms or other adverse reactions occur, the provider should be contacted, and the dosage reduced or discontinued. Stimulants are contraindicated in clients using a monoamine oxidase inhibitor (MAOI) or using an MAOI within the preceding 14 days. See Table 7.6e for an overview of information about stimulants.

Table 7.6e. Stimulants

| Generic | Nursing Considerations | Side/Adverse Effects |

|---|---|---|

|

|

|

Health Teaching About Stimulants

There are several health teaching topics to provide to clients and/or the parents of minor children:

- Controlled Substance Status/High Potential for Abuse and Dependence: Stimulants are a controlled substance by the FDA and can be abused and lead to dependence. Stimulants should be stored in a safe (preferably locked) place to prevent misuse and should not be shared with anyone. Unused or expired stimulants should be disposed of based on state law and regulations or returned to a medicine take-back program if it is available in the community.

- Cardiovascular Risks: Stimulants can increase one’s blood pressure and pulse rate. There is a potential serious cardiovascular risk, including sudden death, cardiomyopathy, myocardial infarction, stroke, and hypertension. Instruct clients to contact a health care provider immediately if they develop symptoms, such as exertional chest pain, dizziness, or passing out.

- Suppression of Growth: Stimulants may cause slowing of growth in children and weight loss.

- Psychiatric Risks: Stimulants can cause psychosis or manic symptoms, even in clients who have no prior history of these symptoms.

- Priapism: Painful or prolonged penile erections can occur; seek immediate medical attention.

- Alcohol: Alcohol should be avoided when taking extended-release capsules.

Nurses should reinforce with the client and their family members that the reason for the prescribed medication is to help with self-control and the ability to focus. Possible side effects should be reviewed, and clients and their family members should be reminded it may take one to three months to determine the best pharmacological treatment, dose, and frequency of medication administration. During this time, the child’s symptoms and adverse effects will be monitored closely and the medication dose adjusted accordingly.

Review additional information in the “CNS Stimulants” section of the “Central Nervous System” chapter in Open RN Nursing Pharmacology, 2e.

- DailyMed. (n.d.). About us. National Library of Medicine. https://dailymed.nlm.nih.gov/dailymed/about-dailymed.cfm ↵

- “Illustration of neurotransmitter” by NIH Image Gallery is licensed under CC BY-NC 2.0 ↵

- Betts, J. G., Young, K. A., Wise, J. A., Johnson, E., Poe, B., Kruse, D. H., Korol, O., Johnson, J. E., Womble, M., & DeSaix, P. (2022). Anatomy and physiology 2e. OpenStax. Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/anatomy-and-physiology-2e/pages/1-introduction ↵

- Sheffler, Z. M. (2023). Physiology, neurotransmitters. StatPearls. [Internet]. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK539894/ ↵

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. (n.d.). Mental health medications. National Institute of Mental Health. https://www.nimh.nih.gov/health/topics/mental-health-medications ↵

Chemicals in the brain that send messages throughout the nervous system.

Involuntary and uncontrolled muscle movements.

Occurs when your body has too much serotonin with symptoms ranging from mental status changes, autonomic hyperactivity, and neuromuscular hyperactivity.

Involuntary contractions of muscles of the extremities, face, neck, abdomen, pelvis, or larynx in sustained or intermittent patterns that lead to abnormal movements or postures.

A syndrome of movement disorders that persists for at least one month and can last up to several years despite discontinuation of the medications.

A rare but fatal adverse effect that can occur at any time during treatment with first- or second-generation antipsychotics.

High blood glucose, symptoms of diabetes (i.e., increased thirst and urination, fatigue, and blurred vision), obesity with a large abdominal girth, hypertension, elevated triglycerides, and lower levels of HDL.

Extremely low white blood cell count.

Painful or prolonged penile erections.