7.3 Suicide Screening and Safety Interventions

Nurses encounter clients having suicidal thoughts in all health care settings. Suicidal ideation refers to thinking about or formulating plans for suicide. Suicidal ideation exists on a spectrum of intensity, from a general desire to die that lacks any concrete method, plan, intention, or action and progressing to active suicidal ideation, which involves a detailed plan and a determined intent to act. Suicidal ideation is a significant safety risk factor for future suicide attempts and death.[1],[2]

Risk Factors and Warning Signs

Several risk factors and warning signs show an increased likelihood a client will consider, attempt, or complete suicide[3]:

- Mental health condition

- Substance use disorders

- Hopelessness

- Impulsiveness

- Isolation

- Previous suicide attempt or family history of suicide

- Job or financial loss

- Loss of relationship

- Access to lethal means

- Exposure to others who have died by suicide

The following warning signs indicate a client may attempt suicide[4]:

- Talk about wanting to die, kill self, or have no reason to live

- Search for a way to kill self like online shopping for a gun

- Talk about feeling trapped or a burden

- Increase use of alcohol or substance(s)

- Act anxiously, agitated, or reckless

- Sleep too much

- Talk about seeking revenge

- Demonstrate extreme mood swings

- Isolate oneself

Several protective factors decrease the likelihood a client will consider, attempt, or complete suicide, such as using effective coping strategies, having a reason for living, such as a relationship or a pet; feeling supported and connected to others; and safely storing guns and prescribed medications in the household.[5]

Suicide Risk Screening

Universal screening for suicidal ideation of clients aged 12 and older admitted to all medical settings allows for the detection of suicide risk and implementation of early safety interventions.

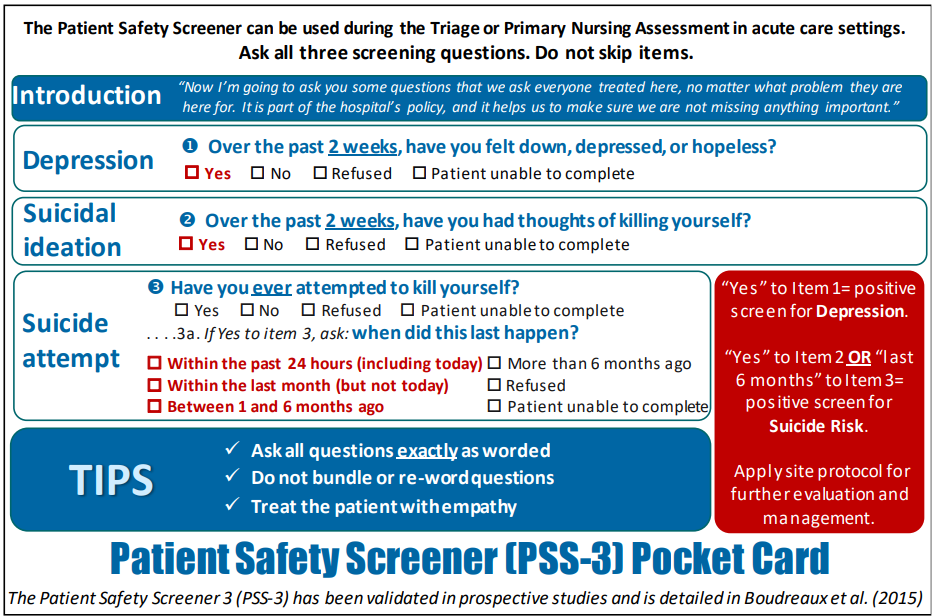

When performing suicide screening, it must be introduced in a way that helps the client understand its purpose and normalize questions that might otherwise seem intrusive. A nurse might introduce the topic in the following way: “Now I’m going to ask you some questions that we ask everyone treated here, no matter what problem they are here for. It is part of the facility’s policy, and it helps us to make sure we are not missing anything important.” It is also important to attend to the client’s answers to help them feel safe divulging information.

The Patient Safety Screener (PSS-3) is an example of a brief screening tool to detect suicide risk in all clients presenting to acute care settings. See Figure 7.2[6] for an image of the PSS-3. The PSS-3 consists of questions about depression, active suicidal ideation, and lifetime suicide attempt.

Each of the items in the PSS-3 addresses a different aspect of suicide risk:

- Depression is a common precipitant of suicidal ideation and behavior and is the most common diagnosis among those who die by suicide.

- Suicidal ideation (i.e., thoughts about killing oneself) is a precondition for suicidal behavior.

- A previous suicide attempt is one of the most consistent risk factors for suicide.

The ASQ Suicide Screening Tool is another example of a screening tool commonly used in medical settings that assesses a client’s risk of attempting suicide. View the questions contained in the ASQ Suicide Screening Tool and instructions for scoring in the following box.

ASQ Suicide Screening Tool[7]

- In the past few weeks, have you wished you were dead?

- In the past few weeks, have you felt that you or your family would be better off if you were dead?

- In the past week, have you been having thoughts about killing yourself?

- Have you ever tried to kill yourself? If yes: How? When?

If the client answers “Yes” to any of the above questions, ask the following acuity question:

- Are you having thoughts of killing yourself right now? If yes, please describe.

Scoring:

- If the client answers “No” to all Questions 1 through 4, screening is complete, and it is not necessary to ask Question #5. No intervention is necessary, although clinical judgment can always override a negative screen.

- If the client answers “Yes” to any of Questions 1 through 4, or refuses to answer, they are considered a positive screen, and Question #5 must be asked to assess severity of risk of suicide.

- If the client answers “Yes” to Question #5, this indicates an acute positive screen with imminent risk. The client requires an immediate evaluation for safety and mental health. The client should not leave until they are evaluated for safety by a health care provider. They should be kept in an area under continuous observation, all dangerous objects should be removed from the room, and the health care provider should be immediately notified.

- If the client answers “No” to Question #5, this indicates a non-acute positive screen with potential risk identified. The client requires a brief suicide safety assessment to determine if a full mental health evaluation is needed. The health care provider should be notified.

Provide these resources to all clients:

- Call 988 to reach the 24/7 National Suicide Prevention Lifeline

- Text “HOME” to 741741 to reach the 24/7 Crisis Text Line

Suicidal thoughts often elevate over a period of time, peak, and then decrease, as depicted in the Suicide Risk Curve depicted in the following box. Helping a client recognize their thoughts and feelings and implementing interventions can help them allow suicidal feelings to pass without acting on them.

View the Suicide Risk Curve PDF.

Implementing Safety Interventions for Clients at Risk for Suicide or Self-Injury

When a client has been identified at risk for suicide or non-suicidal self-injury, nurses must immediately implement safety interventions. Interventions may include therapeutic communication, 1:1 observation by staff, adapting the environment for safety, and implementing safety plans. The environment should be immediately adapted by removing sharp objects, potential ligature points, materials that could be used to hang themselves, pens, aerosol sprays, and mouthwashes.[8] For example, suicidal clients may attempt to hang themselves with sheets, call cords, IV tubing, or stethoscopes, so these items should not be left in the room. They may use sharp objects like pens or paper clips for self-injury or use aerosol sprays, hand sanitizer, or mouthwashes in an attempt to overdose on substances. Nurses must ensure that environmental modifications are made before the client is left alone in a room to help keep them safe.[9],[10]

A common practice for working with clients who have suicidal ideation is to create a written or verbal contract for safety that indicates the client agrees that if they have suicidal ideation, they will ask for help. Unfortunately, evidence indicates that clients with a safety contract may still elect to commit suicide.[11] A better option is to help the client create a safety plan that outlines their strengths and resources to use in case of suicidal ideation. A safety plan includes the following[12]:

- Identifying triggers and situations that place the client at risk for suicidal ideation and avoiding them

- Documenting positive coping strategies that are preferred by the client

- Giving guns and other potentially lethal suicidal methods to a trusted friend for safekeeping

- Identifying trusted support people and providing permission for the health care provider to contact them

- Providing contact information for support groups like NAMI and the Suicide Prevention Hotline (dial 988)

The 988 Suicide & Crisis Lifeline is a national network of local crisis centers available 24 hours a day, seven days a week to support people in crisis or in danger of suicide. View the website at https://988 lifeline.org/ or call or text 988 for help.

- Ernstmeyer, K., & Christman, E. (Eds.). (2022). Nursing: Mental health and community concepts. https://wtcs.pressbooks.pub/nursingmhcc/ ↵

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. (n.d.). Bipolar disorder. National Institute of Mental Health. https://www.nimh.nih.gov/health/topics/bipolar-disorder ↵

- Wisconsin Department of Health Services. (2024). Suicide prevention. https://www.dhs.wisconsin.gov/prevent-suicide/index.htm ↵

- Wisconsin Department of Health Services. (2024). Suicide prevention. https://www.dhs.wisconsin.gov/prevent-suicide/index.htm ↵

- Wisconsin Department of Health Services. (2024). Suicide prevention. https://www.dhs.wisconsin.gov/prevent-suicide/index.htm ↵

- “Patient Safety Screener (PSS-3) Pocket Card” by University of Massachusetts Medical School (UMass Medical) is used on the basis of Fair Use ↵

- National Institute of Mental Health. (2024). Suicide risk screening tool. [PDF]. https://www.nimh.nih.gov/sites/default/files/documents/research/research-conducted-at-nimh/asq-toolkit-materials/asq-tool/screening_tool_asq_nimh_toolkit_0.pdf ↵

- Timberlake, L. M., Beeber, L. S., & Hubbard, G. (2019). Nonsuicidal self-injury: Management on the inpatient psychiatric unit. Journal of the American Psychiatric Nurses Association, 26(1), 10-26. https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/1078390319878878 ↵

- Timberlake, L. M., Beeber, L. S., & Hubbard, G. (2019). Nonsuicidal self-injury: Management on the inpatient psychiatric unit. Journal of the American Psychiatric Nurses Association, 26(1), 10-26. https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/1078390319878878 ↵

- Donovan, A. L., Aaronson, E. L., Black, L., Fisher, S. A., Bird, S. A., Benzer, T., & Temin, E. S. (2021). Keeping patients at risk for self-harm safe in the emergency department: A protocolized approach. The Joint Commission Journal on Quality and Patient Safety, 47(1), 23-30. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S1553725020302154?via%3Dihub ↵

- Hoffman, R. M. (2013). Contracting for safety: A misused tool. Pennsylvania Patient Safety Advisory, 10(2), 82-84. https://patientsafety.pa.gov/ADVISORIES/Pages/201306_82.aspx# ↵

- Hartwell-Walker, M. (2015). The suicidal client: Contracting for safety. PsychCentral. https://psychcentral.com/pro/the-suicidal-client-contracting-for-safety#1 ↵

Refers to thinking about or formulating plans for suicide.