7.14 Eating Disorders

Many people become concerned about their weight at some point in their lives. However, individuals with eating disorders have a distorted view of their weight and their body image and develop an unhealthy relationship with food. As a result of this psychological struggle, behaviors such as severe restriction of food intake, obsessive exercising, binging, and purging can occur. Eating disorders can affect anyone, regardless of gender, age, race, or economic status and can also affect their family members and loved ones. The physiological consequences of eating disorders can be fatal if they are not identified and treated appropriately, due to nutritional deficits and electrolyte abnormalities.[1]

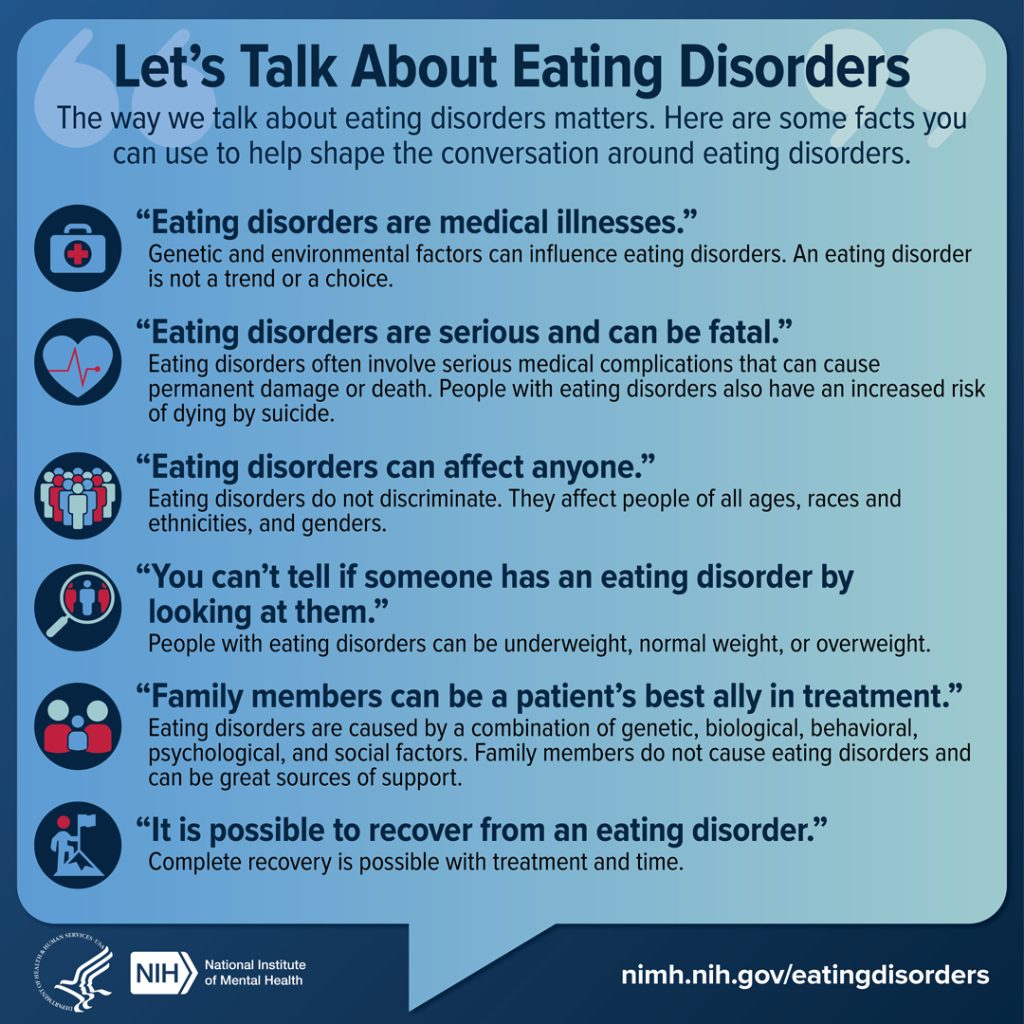

Eating disorders are serious illnesses, and the way that nurses and health care professionals talk about them matters.[2] See Figure 7.8[3] for an infographic with facts nurses can use to help shape the conversation around eating disorders.

Like other mental health disorders, research suggests a combination of factors can increase a person’s risk for developing an eating disorder. In addition to genetics and biology, the environment also plays a significant role. Onset can occur at nearly any point in the life span, but eating disorders commonly start in adolescence and young adulthood when there can be exceptional pressure from peers, social media, and advertisements to diet or lose weight. For those genetically vulnerable to eating disorders, initial weight loss may reinforce a reward feedback mechanism and establish a maladaptive eating behavior pattern. Physiological and sensorial changes result in alterations in hunger and satiety, gastrointestinal motility, and decision-making around food and eating.

Cultural beliefs impact self-concept and satisfaction with body size. Anorexia nervosa is associated with cultures that value thinness. See Figure 7.9[4] for an image of an extremely underweight model in a fashion culture that values thinness. Furthermore, studies indicate that social media significantly influences these beliefs. For example, one study found that participants with higher use of social media had significantly greater odds of having eating concerns. Black and Hispanic teenagers are more likely to suffer from bulimia nervosa. Furthermore, behaviors associated with risks for eating disorders are prevalent in some sport cultures where weight is a consideration, such as in wrestling, gymnastics, figure skating, and bodybuilding.

There are several types of eating disorders, including binge eating disorder, anorexia nervosa, and bulimia nervosa.

Binge Eating Disorder

Binge eating disorder is the most common eating disorder in the United States. A binge eating episode refers to eating large amounts of food in a two-hour period compared to most individuals in a similar period under similar circumstances, along with a sense of a lack of control overeating during the episode.[5] Unlike binge eating episodes that may occur in other eating disorders, associated behaviors like dieting, fasting, or excessive exercise do not occur. As a result, people with binge eating disorder often are overweight or obese.

Anorexia Nervosa

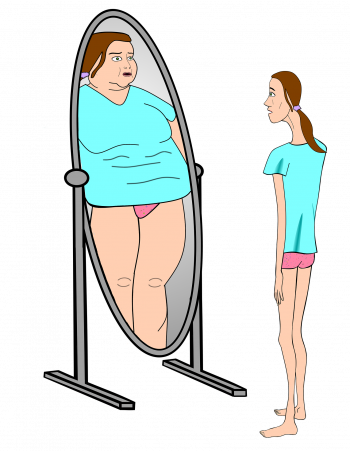

Anorexia nervosa is a condition where people restrict food intake resulting in a significantly low body weight within the context of age, sex, developmental stage, and physical health. They have an intense fear of gaining weight or becoming fat, with persistent behavior that interferes with weight gain, even if they are at a significantly low weight. People with anorexia nervosa have a disturbance in the way they view their weight or body shape and lack recognition of the seriousness of their current low body weight.[6] See Figure 7.10[7] for an illustration of how a person with anorexia nervosa who has a low body weight may perceive their body shape.

There are two subtypes of anorexia nervosa called a “restricting type” and “binge eating/purging” type. People with the restrictive subtype of anorexia nervosa lose weight primarily through dieting, fasting, or excessive exercise. People with the binge-purge subtype have recurrent episodes of binge eating episodes and/or purging. Purging episodes refer to eating large amounts of food in a short time followed by self-induced vomiting or the misuse of laxatives, diuretics, or enemas to eliminate what was consumed.[8]

The severity of clients with anorexia nervosa is based on their body mass index (BMI). BMI greater than 17 is rated as mild, BMI of 16.0 – 16.99 is rated as moderate, BMI of 15.0-15.99 is rated as severe, and BMI less than 15 is rated as extreme.[9]

Additional physiological signs related to anorexia nervosa may develop over time, including the following:

- Thinning of the bones (i.e., osteopenia or osteoporosis)

- Anemia

- Muscle wasting and weakness

- Brittle hair and nails

- Dry and yellowish skin

- Growth of fine hair all over the body (lanugo)

- Severe constipation

- Low blood pressure

- Slowed breathing and pulse

- Drop in internal body temperature, causing the person to feel cold all the time

- Lethargy, sluggishness, or feeling tired all the time

- Infertility

- Damage to the structure and function of the heart

- Brain damage

- Multiorgan failure

Anorexia nervosa has a high mortality (death) rate compared with other mental health disorders due to medical complications associated with starvation or due to suicide.[10]

Bulimia Nervosa

Bulimia nervosa is a condition where people have recurrent episodes of binge eating followed by inappropriate compensatory behaviors to prevent weight gain such as self-induced vomiting; misuse of laxatives, diuretics, or other medications; or excessive exercise. The binge eating and inappropriate compensatory behaviors occur, on average, at least once a week for three months. Individuals with bulimia nervosa also have a disturbance in the way they view their weight or body shape. The severity of Bulimia Nervosa is based on how frequently compensatory behaviors occur, unlike Anorexia Nervosa, where severity is determined by BMI.[11]

Signs and symptoms of bulimia nervosa include the following:

- Chronically inflamed and sore throat

- Swollen salivary glands in the neck and jaw area

- Worn tooth enamel and increasingly sensitive and decaying teeth as a result of exposure to stomach acid

- Acid reflux disorder and other gastrointestinal problems

- Intestinal distress and irritation from laxative abuse

- Severe dehydration from purging of fluids

- Electrolyte imbalance (sodium, calcium, potassium, and other minerals) that can lead to dysrhythmias and cardiac arrest

Assessment of Eating Disorders (Recognizing Cues)

Nurses are often the first point of contact with clients with undiagnosed eating disorders and play an essential role in identifying unhealthy patterns of eating, purging, or excessive exercise. They often recognize signs and symptoms of a possible eating disorder during routine assessments of vital signs, weight, and nutritional trends.[12]

If an eating disorder is suspected, a comprehensive nursing assessment includes mental status examination, psychosocial assessment, and screening for risk of suicide or self-harm, as well as assessment of BMI, nutritional intake, fluid intake, and daily exercise. If the client experiences binge eating episodes, the amount of food eaten within specific time periods and the frequency of these behaviors should be assessed and documented. If the client experiences purging or inappropriate compensatory behaviors such as self-induced vomiting, misuse of laxatives, diuretics, or enemas, or excessive exercise, the frequency of these behaviors should be documented. Nurses should also assess and document the client’s perception of their weight and body shape.[13]

Objective assessments include routine weight monitoring and orthostatic vital signs. During inpatient care, nurses may also observe and document behaviors such as bathroom visits following meals, stashing food, concealed eating, or excessive physical activity.

Common objective assessment findings for individuals with anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa are compared in Table 7.14. Clients with binge eating disorder may have obesity and gastrointestinal symptoms but do not typically have other associated abnormal assessment findings.

Table 7.14. Comparison of Assessment Findings for Anorexia Nervosa and Bulimia Nervosa

| Anorexia Nervosa | Bulimia Nervosa |

|---|---|

| Low weight | Normal to slightly low weight |

| Muscle weakening (from starvation and electrolyte imbalance) | Muscle weakening (from electrolyte imbalance) |

| Peripheral edema (from hypoalbuminemia) | Peripheral edema (from rebound fluids if diuretics are used) |

| Cardiovascular abnormalities (hypotension, bradycardia, heart failure from starvation, and dehydration) | Cardiovascular abnormalities (cardiomyopathy and cardiac dysrhythmias from electrolyte imbalances) |

| Abnormal lab results (hypokalemia and anemia from starvation) | Electrolyte imbalances (hypokalemia and hyponatremia from diuretics, laxatives, or vomiting) |

| Other signs:

Amenorrhea (lack of menstruation) Lanugo (growth of fine hair all over the body) Cold extremities Constipation Impaired renal function Decreased bone density |

Other signs:

Tooth erosion or dental caries (from vomiting reflux over enamel) Parotid swelling (due to increased serum amylase levels) Calluses or scars on hand (from self-inducing vomiting) Seizures (purging via self-induced vomiting lowers seizure threshold) |

Nurses may also assess a client’s body mass index (BMI) as part of initial screening. BMI has become a standard way to measure body proportion because it is easy to calculate and a weight classification is identified using categories of underweight, normal, overweight, or obese. However, recent research indicates BMI should be used cautiously. Because BMI only measures the ratio of weight to height, it cannot account for other factors that influence weight and body composition such as a person’s musculature or bone density, which diminishes its validity as a measure of weight status. It can also be problematic when caring for clients with eating disorders. While a very low or rapidly decreasing BMI is a reliable indicator that a client requires medical treatment, clients with a normal or elevated BMI can also have an eating disorder that could be missed. Furthermore, an elevated BMI may increase the risk for developing an eating disorder when clients restrict their food intake in pursuit of an ideal BMI. For these reasons, BMI must be used with other indicators to determine a healthy weight.[14],[15],[16]

Laboratory and diagnostic tests are commonly performed for clients with suspected eating disorders to rule out thyroid imbalances and to evaluate for potential physiological complications resulting from starvation, dehydration, and electrolyte imbalances. Tests may include the following:

- Complete blood count

- Electrolyte levels

- Glucose level

- Thyroid function tests

- Erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR)

- Creatine phosphokinase (CPK)

- Electrocardiogram (ECG)

- Dual energy X-ray absorptiometry (DEXA) to measure bone density

Treatment of Eating Disorders

A variety of treatments are effective for eating disorders. Early treatment for eating disorders is crucial because of the increased risk for medical complications, suicide, and self-injury behaviors. People with eating disorders may also have coexisting mental health disorders (such as depression or anxiety) or problems with substance misuse. Generally, treatment is most effective if the disorder is detected before it becomes chronic, but even people with long-standing eating disorders can recover with proper treatment.

Health care professionals must be cautious with word choices about weight, BMI, appearance, and food intake, and instead emphasize healthy behaviors and coping strategies such as good nutrition, restful sleep, regular physical activity, maintaining social connections, and participating in hobbies. Clients recovering from eating disorders may be sensitive to hearing or visualizing their weight on the scale and find it to be triggering for ruminating about their eating behaviors.[17],[18]

Treatment plans are tailored to individual needs and may include medications, individual, family, and group psychotherapy, medical care, and nutritional support. These treatments are discussed in the following subsections.

Medications

Medications such as antidepressants, antipsychotics, or mood stabilizers may be prescribed by the health care provider. However, bupropion and tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs) should not be used due to their potential cardiotoxicity, and bupropion also increases the risk for seizures. Read more about these medications in the “Psychotropic Medications” section of this chapter.

Psychotherapy

Cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) is used to reduce or eliminate binge eating and purging behaviors. Individuals learn how to identify distorted or unhelpful thinking patterns and recognize and change inaccurate beliefs. Read more about CBT in the “Psychotherapy” section of this chapter.

Family-based therapy is a type of psychotherapy where parents of adolescents with anorexia nervosa assume responsibility for feeding their child. This therapy has been found to be very effective in helping adolescents gain weight and improve eating habits and moods.

Group therapy with peers who are also experiencing eating disorders can be helpful in helping clients establish a healthy perspective on body weight and body shape.

Medical Care and Nutritional Support

Clients with severe eating disorders may require hospitalization and nutritional rehabilitation through tube feeding or total parenteral nutrition (TPN). However, clients who do not recognize the seriousness of their extremely low body weight may refuse treatment and require additional counseling by the interprofessional health care team. Additionally, a complication called refeeding syndrome may occur for clients with severe malnutrition, resulting in life-threatening electrolyte imbalances. Nurses must carefully monitor electrolyte balances when administering tube feeding or TPN to clients with severe eating disorders.[19]

Nutritional rehabilitation for adolescent clients during periods of growth is especially important. Research indicates TPN therapy for adolescents can be effective for treating malnutrition and recovering their appetite without refusal behaviors.[20]

Nutritional counseling by a dietician with specialized training is crucial for individuals with eating disorders. Counseling includes education about nutritional needs, as well as planning healthy food choices.

Some clients may pursue complementary therapies for treating eating disorders, such as acupuncture, biofeedback, or other homeopathic remedies. As with all complementary therapies, nurses encourage clients to discuss the risks and benefits of complementary therapies with their health care provider to make an informed decision.

The Mental Health America website provides an analysis of Complementary and Alternative Medicine for Mental Health Conditions.

Nursing Interventions

It is vital for nurses to build a therapeutic nurse-client relationship with clients with eating disorders while seeking to understand their perspective of the disorder. Individuals with anorexia nervosa often do not view their behavior as a problem and are typically seen in health care settings due to concerned family or friends who encourage them to seek treatment. Conversely, individuals with bulimia nervosa or binge eating disorder may feel shame and sensitivity to the perceptions of others regarding their illness. Nurses must use conscious language with clients with eating disorders and avoid commenting on their weight, appearance, or food intake.

Nursing interventions may include the following[21]:

- Monitor weight and BMI; ask the client if they want to be aware of their weight/ BMI or if they find this triggering

- Monitor food and fluid intake

- Monitor fluid output and bowel patterns

- Assess for inappropriate compensatory behaviors such as fasting; self-induced vomiting; inappropriate use of laxatives, diuretic, or enemas; or excessive exercise

- During inpatient or residential care, supervise activity after meals to prevent purging behaviors or excessive exercise

- Prevent pressure injuries in clients with malnutrition

- Monitor for signs of complications such as irregular cardiac rate or rhythm, hypotension, or electrolyte imbalances

- Encourage constructive positive self-talk and compliment them on qualities other than weight, appearance, or food intake

- Assist the client to create achievable goals and plan healthy meals

- Involve family members and/or friends with the treatment plan, as appropriate

- Provide information on support groups

Health Teaching

In addition to teaching clients about eating disorders, prescribed medications, and other treatments, nurses teach clients about using stress management and healthy coping strategies to manage their emotional responses. Stress management techniques include engaging in regular physical exercise, selecting healthy food choices, setting personal and professional boundaries, and maintaining a healthy social support network. Additional stress management strategies include the techniques of grounding, unhooking, acting on our values, being kind, and making room. Emotion-focused coping refers to strategies used to manage one’s emotional responses, such as participating in mindfulness, meditation, or yoga; using humor and jokes; seeking spiritual or religious pursuits; breathing exercises; and seeking social support. Review additional information about these strategies in the “Applying the Nursing Process and Clinical Judgment Model to Promote Healthy Coping” in the “Mental Health Concepts” chapter.

- Ernstmeyer, K., & Christman, E. (Eds.). (2022). Nursing: Mental health and community concepts. https://wtcs.pressbooks.pub/nursingmhcc/ ↵

- Ernstmeyer, K., & Christman, E. (Eds.). (2022). Nursing: Mental health and community concepts. https://wtcs.pressbooks.pub/nursingmhcc/ ↵

- “2020_eatingdisorderinfographics_final.jpg” by U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Mental Health is in the Public Domain. ↵

- “7991065935_8f05b38f46_k” by Farrukh is licensed under CC BY-NC 2.0 ↵

- American Psychiatric Association. (2022). Desk reference to the diagnostic criteria from DSM-5-TR (5th ed.). American Psychiatric Association Publishing. ↵

- American Psychiatric Association. (2022). Desk reference to the diagnostic criteria from DSM-5-TR (5th ed.). American Psychiatric Association Publishing. ↵

- “maxpixel.net/Bulimia-Anorexia-Nervosa-Skimmed-Delusional-4049661.png” by unknown author is licensed under CC0 ↵

- American Psychiatric Association. (2022). Desk reference to the diagnostic criteria from DSM-5-TR (5th ed.). American Psychiatric Association Publishing. ↵

- American Psychiatric Association. (2022). Desk reference to the diagnostic criteria from DSM-5-TR (5th ed.). American Psychiatric Association Publishing. ↵

- National Institute of Mental Health. (2024). Eating disorders. https://www.nimh.nih.gov/health/topics/eating-disorders ↵

- American Psychiatric Association. (2022). Desk reference to the diagnostic criteria from DSM-5-TR (5th ed.). American Psychiatric Association Publishing. ↵

- Dugan, J. (2024). Nurse’s guide to caring for patients with eating disorders. NurseJournal. https://nursejournal.org/resources/caring-for-patients-with-eating-disorders/ ↵

- American Psychiatric Association. (2022). Desk reference to the diagnostic criteria from DSM-5-TR (5th ed.). American Psychiatric Association Publishing. ↵

- Bunnell, D. (n.d.). Body mass index (BMI). National Eating Disorders Association. https://www.nationaleatingdisorders.org/bmi/ ↵

- Toppino, F., Longo, P., Martini, M., Abbate-Daga, G., & Marzola, E. (2022). Body mass index specifiers in anorexia nervosa: Anything below the “extreme”? Journal of Clinical Medicine, 11(3), 542. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm11030542 ↵

- Mishra, K., & Harrop, E. (2023). Teaching how to avoid overreliance on BMI in diagnosing and caring for patients with eating disorders. AMA Journal of Ethics, 25(7), 507-513. https://journalofethics.ama-assn.org/article/teaching-how-avoid-overreliance-bmi-diagnosing-and-caring-patients-eating-disorders/2023-07 ↵

- Mishra, K., & Harrop, E. (2023). Teaching how to avoid overreliance on BMI in diagnosing and caring for patients with eating disorders. AMA Journal of Ethics, 25(7), 507-513. https://journalofethics.ama-assn.org/article/teaching-how-avoid-overreliance-bmi-diagnosing-and-caring-patients-eating-disorders/2023-07 ↵

- Dugan, J. (2024). Nurse’s guide to caring for patients with eating disorders. NurseJournal. https://nursejournal.org/resources/caring-for-patients-with-eating-disorders/ ↵

- Tamura, A., Minami, K., Tsuda, Y., & Yoshikawa, N. (2015). Total parenteral nutrition treatment efficacy in adolescent eating disorders. Pediatrics International, 57(5), 947-953. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/ped.12717 ↵

- WebMD. (2023). What is refeeding syndrome? https://www.webmd.com/mental-health/eating-disorders/anorexia-nervosa/what-is-refeeding-syndrome ↵

- Dugan, J. (2024). Nurse’s guide to caring for patients with eating disorders. NurseJournal. https://nursejournal.org/resources/caring-for-patients-with-eating-disorders/ ↵

Distorted view of weight, body image, and unhealthy relationship with food.

Eating large amounts of food in a 2 hour period compared to most individuals in a similar period under similar circumstances, along with a sense of a lack of control over eating during the episode.

A condition where people restrict food intake resulting in a significantly low body weight within the context of age, sex, developmental stage, and physical health.

Refer to eating large amounts of food in a short time followed by self-induced vomiting or the misuse of laxatives, diuretics, or enemas to eliminate what was consumed.

Growth of fine hair all over the body.

A condition where people have recurrent episodes of binge eating followed by inappropriate compensatory behaviors to prevent weight gain such as self-induced vomiting; misuse of laxatives, diuretics, or other medications; or excessive exercise.