6.5 Substance Misuse

Substance misuse is another type of maladaptive behavior some people use for coping with stressful or unpleasant situations. Substance misuse is defined as the use of alcohol or drugs in a manner, situation, amount, or frequency that could cause harm to the user or to those around them.[1] Misuse can be of low severity and temporary, but it can increase the risk for serious and costly consequences such as motor vehicle crashes, overdose, sexually transmitted disease, unintended pregnancies, and death by suicide, overdose, or other accidents. Sixteen percent of the U.S. population aged 12 or older have a substance use disorder (SUD), with the highest percentage in young adults aged 18 to 25. Annually, approximately 140,000 people die from alcohol-related causes, making alcohol the fourth-leading preventable cause of death in the United States. Substance misuse has far-reaching adverse effects that can impact the cardiovascular, respiratory, nervous, and reproductive systems. However, despite these impacts, 94% of people with an SUD do not receive treatment. It is crucial for nurses to recognize signs and symptoms of substance misuse and initiate guidance on treatment.[2],[3]

Substance Use Disorders

According to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5-TR), substance use disorder (SUD) is a problematic pattern of substance use leading to clinically significant impairment. Substances include alcohol, caffeine, cannabis, hallucinogens, inhalants, opioids, sedatives, hypnotics, anxiolytics, stimulants (amphetamines, cocaine, and other stimulants), tobacco, or other substances like nitrous oxide.[4] All these substances taken in excess have a common effect of directly activating the brain reward system and producing such an intense activation of the reward system that normal life activities may be neglected. Nonsubstance-related disorders such as gambling disorder activate the same reward system in the brain.[5]

Substance use disorders are diagnosed based on cognitive, behavioral, and psychological symptoms that are similar across substances. See the DSM-5-TR diagnostic criteria used for SUD in the following box. SUD may manifest with mild, moderate, or severe signs and symptoms.[6]

DSM-5-TR Criteria for Substance Use Disorder

SUD diagnosis requires the presence of two or more of the following criteria in a 12-month period[7]:

- The substance is often taken in larger amounts or over a longer period than intended.

- There is a persistent desire or unsuccessful efforts to cut down or control substance use.

- A great deal of time is spent in activities necessary to obtain the substance, use the substance, or recover from its effects.

- There is a craving, or a strong desire or urge, to use the substance.

- There is recurrent substance use, resulting in a failure to fulfill major role obligations at work, school, or home.

- There is continued substance use despite having persistent or recurrent social or interpersonal problems caused by or exacerbated by the effects of the substance.

- Important social, occupational, or recreational activities are given up or reduced because of substance use.

- There is recurrent substance use in situations in which it is physically hazardous.

- Substance use is continued despite knowledge of having a persistent or recurrent physical or psychological problem that is likely to have been caused or exacerbated by the substance.

- Tolerance develops to the substance, as defined by:

- A need for markedly increased amounts of the substance to achieve intoxication or the desired effect.

- There is a markedly diminished effect with continued use of the same amount of the substance.

- Withdrawal symptoms occur when substance use is cut back or stopped following a period of prolonged use.

Clinicians also indicate if an individual is in early remission, meaning none of the criteria have been met for three months, or sustained remission, meaning none of the criteria have been met for 12 months or longer.[8]

Severe substance use disorders have been historically referred to as addiction. However, addiction is no longer a diagnosis by the American Psychiatric Association because of its potentially negative connotation.[9]

Neurobiology of Substance Use Disorders

Substance use disorders, commonly referred to as addictions, were once considered a moral failing or character flaw, but they are now classified as a chronic brain disease. All addictive substances have powerful effects on a person’s brain. These effects account for the euphoric or intensely pleasurable feelings that people experience during their initial use of alcohol or other substances. These feelings may motivate people to use those substances again and again, especially as maladaptive coping behaviors, despite the risks for significant harm.

As individuals continue to misuse alcohol or other substances, progressive changes, called neuroadaptations, occur in the structure and function of the brain. These neuroadaptations drive the transition from controlled, occasional substance use to chronic misuse that can be difficult to control and can endure long after an individual stops using the substances.[10],[11]

Three regions of the brain are involved in the development and persistence of substance use disorders: basal ganglia, extended amygdala, and prefrontal cortex[12]:

- The basal ganglia control the rewarding, pleasurable effects of substance use and are responsible for the formation of habitual substance taking.

- The extended amygdala is involved in the stress response and the feelings of unease, anxiety, and irritability that typically accompany substance withdrawal.

- The prefrontal cortex is involved in executive function (e.g., the ability to organize thoughts and activities, prioritize tasks, manage time, and make decisions), including exerting control over substance use.

See Figure 6.5[13] for an illustration of the regions of the brain associated with SUD. These changes in the brain persist long after substance use stops and are associated with a high incidence of relapse with substance use disorders.[14]

![Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (US); Office of the Surgeon General (US). Facing addiction in America: The surgeon general's report on alcohol, drugs, and health [Internet]. Washington (DC): US Department of Health and Human Services; 2016 Nov. Figure 2.3, The Three Stages of the Addiction Cycle and the Brain Regions Associated with Them. Used under Fair Use. Available from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK424849/figure/ch2.f3/ Image showing the Regions of the Brain Associated with Substance Use Disorder](https://wtcs.pressbooks.pub/app/uploads/sites/48/2024/07/Areas-of-Brain-Associated-with-SUD-ch2f2.jpg)

As a person continues to misuse substances, neuroadaptations in these areas of the brain reduce a person’s ability to control their substance use. Each area is associated with a stage of SUD[15]:

- Binge/Intoxication: The stage at which an individual consumes an intoxicating substance and experiences its rewarding or pleasurable effects.

- Withdrawal/Negative Affect: The stage at which an individual experiences a negative emotional state in the absence of the substance.

- Preoccupation/Anticipation: The stage at which one seeks substances again after a period of abstinence.

When used long-term, all addictive substances cause dysfunction in the brain’s dopamine reward system. For example, brain imaging studies in individuals with addictions show long-lasting decreases in dopamine receptors even after stopping substance misuse. This three-stage model provides a useful way to understand the symptoms of SUD, the ways it can be prevented and treated, and the steps for recovery.[16]

Risk Factors for Substance Use Disorders

SUD often develops gradually over time. Multiple factors influence whether a person will develop a substance use disorder such as the substance itself; the genetic vulnerability of the user; the amount, frequency, and duration of the misuse; environmental factors such as the availability of drugs; family and peer dynamics; financial resources; cultural norms; exposure to stress; and access to social support. People who have experienced adverse childhood effects (ACE) are at elevated risk for developing SUD. There is also a complex relationship between mental health disorders and SUD; mental health disorders may contribute to the development of SUD, and SUD may contribute to the development of mental health disorders. Individual factors that increase the risk of SUD are initiating substance use at a young age, having a rebellious personality, experiencing emotional distress, and demonstrating favorable attitudes toward using substances. Family risk factors that contribute to development of a SUD are conflict, parental approval of substance use, and family history of substance use.[17]

Clients with SUD often have difficulty with emotional self-regulation. People need outlets for intense emotions, and some use substances to help with emotional regulation. It appears emotional dysregulation can influence a person to start misusing substances and is also an effect of SUD.[18]

Common Types of Substance Misuse

Several types of substances can be misused. This subsection will discuss the most commonly misused substances, including alcohol, opioids, and cannabis, as well as nonsubstance-related disorders.

Alcohol

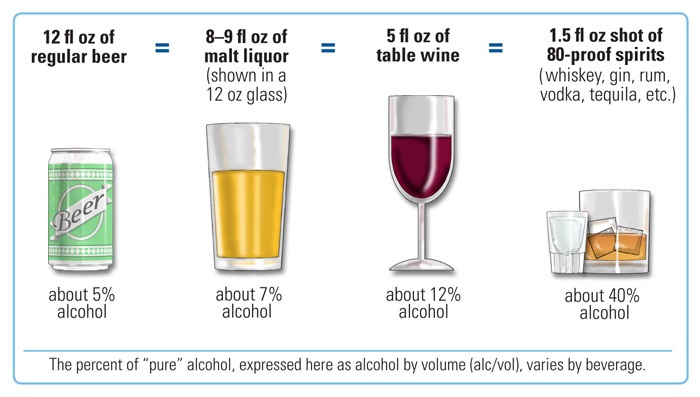

According to the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, drinking alcohol in moderation means limiting alcohol intake to two drinks or less per day for men and one drink or less per day for women. A standard drink of alcohol is defined as 14 grams (0.6 ounces) of pure alcohol. Examples of a standard drink are one 12-ounce beer, 8 – 9 ounces of malt liquor, 5 ounces of wine, or 1.5 ounces of distilled spirits.[19] See Figure 6.6[20] for an illustration of a standard drink.

Alcohol intoxication includes one or more of the following signs or symptoms that develop during or shortly after alcohol use[21]:

- Slurred speech

- Incoordination

- Unsteady gait

- Nystagmus

- Impaired attention or memory

- Stupor or coma

When females drink four or more drinks per two-hour session and males drink five or more drinks in a two-hour session, it is classified as binge drinking. Binge drinking brings the blood alcohol concentration level to 0.08% or more. Binge drinking can be deadly. Furthermore, children, adolescents, and young adults who binge drink alcohol are more likely to experience problems with school, the law, physical injuries, brain development, and memory.[22],[23]

Alcohol use disorder (AUD) is the most common SUD in the United States, including use by children and adolescents. Excessive alcohol use contributes to health problems such as depression, hypertension, injury, liver disease, cancer, and drug interactions with prescribed medications. Family members of a client with AUD also have more health problems than family members without AUD, so screening for and treating AUD helps entire families.[24]

Cannabis

The use of cannabis (marijuana) in the United States is growing, although many people do not understand its risks. Children, adolescents, young adults, and pregnant and nursing women are at highest risk for adverse effects. One in ten adults develops a cannabis-related SUD, and for those who start using cannabis before age 18, one in six develops SUD. The potential negative effects of marijuana misuse are loss of brain function; impaired mental, athletic, and driving abilities; fetal growth restriction, premature birth, stillbirth, or impaired fetal brain development; relationship problems; lower educational and career outcomes; and reduced life satisfaction.[25]

Cannabis intoxication includes two or more of the following signs or symptoms that develop within two hours after cannabis use[26]:

- Conjunctival erythema

- Increased appetite

- Dry mouth

- Tachycardia

Opioids

Opioids are a substance found in certain prescription pain medications and illegal drugs like heroin. Opioid use disorder (OUD) refers to the chronic use of opioids that causes clinically significant distress or impairment. Opioids are prescribed to treat pain, but with prolonged use the body can develop physical dependence, resulting in withdrawal symptoms when the person tries to stop taking them. Taking more than the prescribed amount of opioids or using illegal opioids like heroin can result in overdose and death.[27]

Opioid intoxication includes pupillary constriction and one or more of the following signs or symptoms that develop during or shortly after opioid use[28]:

- Drowsiness or coma

- Slurred speech

- Impaired attention or memory

OUD occurs in individuals from all educational and socioeconomic backgrounds. Individuals at higher risk for OUD include those deficient in neurotransmitters such as dopamine or those with first-degree relatives who have been diagnosed with a substance abuse disorder. Environmental risks for OUD include peer use of opioids or exposure to opioid analgesics prescribed for a previous injury. Additionally, clients with a history of untreated depression, post-traumatic stress disorder, anxiety, or childhood trauma are also at risk for OUD.[29]

The United States has been in the midst of an opioid crisis since the 1990s when increased prescriptions of opioid pain medication led to a rise in misuse and overdose deaths. In 2016 the CDC published guidelines on prescribing opioids for pain. However, these guidelines led to limited prescriptions of opioids with unintended consequences, such as forced tapering of medications for established clients requiring chronic pain control, resulting in some clients transitioning to using illicit drugs such as heroin for pain control. In 2022 the CDC released new guidelines for prescribing opioids for pain. The CDC recommends that people experiencing pain receive appropriate pain treatment, with careful consideration of the benefits and risks of all treatment options in the context of the client’s circumstances. The guidelines are intended to improve communication with clients about the benefits and risks of opioid therapy; improve function and quality of life for clients with pain; and reduce risks associated with opioid use disorder, overdose, and death.[30]

Nonsubstance-Related Disorders

Nonsubstance-related disorders are excessive behaviors related to gambling, viewing pornography, compulsive sexual activity, Internet gaming, overeating, shopping, overexercising, and overusing mobile phone technologies. These behaviors are thought to stimulate the same addiction centers of the brain as addictive substances. However, gambling disorder is the only nonsubstance use disorder with diagnostic criteria listed in the DSM-5-TR.[31]

Gambling disorder is indicated by four or more of the following signs or symptoms[32]:

- Needs to gamble with increasing amounts of money in order to achieve the desired excitement

- Is restless or irritable when attempting to cut down or stop gambling

- Has made repeated unsuccessful attempts to control, cut back, or stop gambling

- Is preoccupied with gambling with persistent thoughts of reliving past gambling behaviors, planning the next venture, or thinking of ways to get money with which to gamble

- Often gambles when feeling distressed

- After losing money gambling, often returns another day to get even

- Lies to conceal the extent of involvement with gambling

- Has jeopardized or lost a significant relationship, job, or educational or career opportunity because of gambling

- Relies on others to provide money to relieve desperate financial situations caused by gambling

Impact of Substance Use Disorders on Others

Substance use disorder is a family disease, in addition to an individual disease. When a person in a family misuses substances, all family members can be affected. For example, a parent with SUD may not fulfill their parenting role in raising children or assist with finances for the family, resulting in their spouse assuming a disproportionately large amount of the household responsibilities. A family member may exhibit aggressive or hostile behavior when intoxicated. Children of a parent with SUD often feel lonely, guilty, anxious, helpless, depressed, and fear abandonment. They are also susceptible to behavioral or emotional problems, as well as developing SUD. Parents and grandparents of a child or adolescent with SUD may develop excessive caregiver burden with associated emotional distress. These are some examples of family dysfunction that may occur as a result of a family member with SUD.[33]

Read additional information about family dysfunction in the “Family Dynamics” chapter.

Codependency

A dysfunctional relationship pattern called codependency can develop in a person who is affected by another person’s substance misuse. This learned emotional and behavioral condition may contribute to the person with SUD avoiding taking responsibility for their behavior. Family members may deny problems, repress their emotions, and disregard their personal needs. The person exhibiting codependence may be a parent, child, spouse, partner, friend, or coworker, and may also be a person with SUD. Codependence can also be passed down through generations by learned behavior.[34],[35]

A person exhibiting codependence may take responsibility to fix problems that belong to the person with SUD, demonstrate poor boundaries, and set poor limits. When the codependent person assists the client with SUD more than they should, this is called enabling because it actually helps the client with SUD avoid changing behavior. The codependent person may exhibit role shifting, which refers to completing activities that should be the responsibility of someone else. For example, a child may take responsibility for completing household tasks or performing childcare for their siblings rather than the parent who has SUD.[36],[37]

A person with codependency meets the other person’s needs rather than their own, which makes the relationship one-sided. They feel self-esteem by helping the other person. While empathy is a positive trait, in codependency there is too much empathy for the other person; in a healthy relationship both parties mutually rely upon each other.[38]

Additional signs of codependency are as follows[39]:

- Avoiding conflict

- Needing to ask permission for daily tasks

- Apologizing even though one has done nothing wrong

- Trying to change, rescue, or fix others, which they interpret as love

- Needing to help others to feel good about oneself

- Helping even if it feels uncomfortable

- Losing sense of self and free time for self

- Taking too much responsibility most of the time

- Having an extreme need for approval and recognition and disappointment without it

- Attempting to control others

- Feeling guilty if they assert themselves

- Fearing abandonment

- Lacking trust

- Poor communication

- Difficulty making decisions

Health teaching and therapy can help people with codependency regain their sense of self, set boundaries, experience feelings, and create healthy relationships.[40] People with codependency may also find help by attending a 12-step support group like Al-Anon. Al-Anon is similar to Alcoholics Anonymous (AA), but it has been developed for people affected by another person’s alcohol use disorder. Other support groups exist for people affected by other types of substance use, such as Nar-Anon for those affected by another’s addiction.

Read more about Al-Anon at the Al-Anon website or Nar-Anon at Nar-Anon website.

Myths About Substance Use Disorders

There are several myths surrounding the causes and treatment of SUD. View several myths and the corresponding reality in the following box.

Myths and Realities About SUD[41]:

- Myth: Using drugs or alcohol is a choice, so if someone gets addicted, it’s their fault.

- Reality: Addiction is a consequence of many contributing factors, including genetics, neurobiology, adverse childhood effects (ACEs), trauma, and other influences.

- Myth: If someone just uses willpower, they should be able to stop using the substance.

- Reality: For people who are genetically vulnerable to addiction, substance use can cause profound changes in the brain that hijack the reward pathway of the brain. Addictive substances flood the brain with neurotransmitters that signal pleasure. These changes create intense impulses to continue using the substances despite negative consequences of doing so.

- Myth: Addiction affects certain types of people.

- Reality: Addiction can affect anyone, irrespective of age, income, ethnicity, religion, family, or profession.

- Myth: If someone has a stable job and family life, they can’t be experiencing addiction.

- Reality: Anyone is vulnerable to addiction. Many people hide the severity of their illness or don’t get help because of stigma or shame.

- Myth: People have to become seriously ill before they can get well.

- Reality: The longer a person waits to get help, the more changes happen to the brain, which can have deadly consequences like overdose. Studies show that people forced into treatment have an equal chance of successful recovery as people who initiate treatment on their own.

- Myth: Going to rehab will fix the problem.

- Reality: SUD is a chronic disease, similar to hypertension or diabetes, that can be controlled but not cured. Treatment is the first step toward wellness; staying well requires a lifelong commitment to managing this chronic disease.

- Myth: If someone relapses, they can never get better.

- Reality: Relapse is no more likely with addiction than other chronic illnesses like diabetes. Getting well involves changing deeply embedded behaviors that are significantly rewarded in the brain. Behavioral change takes time and effort, and setbacks can occur. A relapse can signal that the treatment approach or other supports need to change or that other treatment methods are needed. There is hope that people who experience a relapse will return to recovery.

Treatment of Substance Use Disorders

Individuals with substance use disorder can overcome their disorder with effective treatment and regain health and social function, referred to as remission. When positive changes and values become part of a voluntarily adopted lifestyle, this is referred to as “being in recovery.”[42]

Recovery

Recovery is a process of change through which individuals improve their health and wellness, live a self-directed life, and strive to reach their full potential. Although abstinence from substance misuse is a primary feature of a recovery lifestyle, it is not the only healthy feature. Other features of recovery are acceptance of the condition; transforming identity or spirituality; and reconstructing attitudes, beliefs, roles, and goals. Clients with social support, religiosity, life meaning, and affiliation with 12-step support groups are most likely to thrive in recovery. Additional resources to help clients recover are community activities, housing, self-care tools, and peer support.[43],[44] Among the 29.2 million adults in 2020 who have ever had a substance use problem, 72.5 percent considered themselves to be in recovery.[45]

Relapse

SUD is a chronic illness that has the potential for relapse. Relapse refers to the individual returning to substance use after a significant period of abstinence. The chronic nature of SUD means that some individuals may relapse after an attempt at abstinence, which can be a normal part of the recovery process. Relapse does not mean treatment failure. Relapse rates for substance use are similar to rates for adherence to therapies for other chronic medical illnesses. There are a variety of medications that can be prescribed to assist with relapse prevention.[46]

Medications Used to Treat Substance Use Disorders

Medications and psychotherapy can successfully treat SUD. Medications are used to help relieve withdrawal symptoms and psychological cravings that cause chemical imbalances in the body. These medications are nonaddictive and do not cure the disorder but help clients manage their chronic problem.[47] Medications prescribed to treat a variety of types of SUD are summarized in Table 6.5.

Table 6.5. Medications Used to Treat Substance Use Disorders[48],[49],[50]

| Use | Example | Special Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Alcohol Use Disorder | Acamprosate | Prescribed to promote abstinence from alcohol and may improve cognitive function after stopping drinking. |

| Alcohol Use Disorder | Disulfiram | Prescribed to promote abstinence from alcohol by causing unpleasant feelings of heart palpitations, nausea, and flushing when alcohol is ingested. |

| Alcohol Use Disorder and

Opioid Use Disorder |

Naltrexone | Prescribed to block opioid receptors, reduce cravings, and diminish rewarding effects of opioids and alcohol in the brain. Also used to treat opioid overdose. |

| Alcohol Use Disorder | Vitamins: Thiamine and

Magnesium |

Chronic alcohol use is associated with depletion of thiamine and magnesium. |

| Opioid Use Disorder | Buprenorphine | Used to manage withdrawal symptoms and to maintain abstinence from opioids. |

| Opioid Use Disorder | Methadone | Reduces cravings or withdrawal and blocks/blunts effects of opioids; only administered at certified and approved centers. |

Nonpharmacological Treatments to Promote Recovery

Several nonpharmacological treatments are used to promote recovery. Efforts toward recovery include abstinence, honesty, and learning how to cope with uncomfortable emotions without using substances.

It may take four to five years for a client to achieve recovery and return to the same risk level for SUD as the general population. The client’s treatment plan should be individualized to their needs, desires, and culture. The following treatments are recommended for clients with SUD[51]:

- Interventions focused on health teaching and motivational interviewing to help clients with SUD connect their goals to their behavior.

- Concurrent treatment of medical conditions with special considerations for pharmacological treatment of chronic pain.

- Behavioral therapies that teach and motivate clients to change their behaviors as a way to control their substance use disorders. Individual, family, or group counseling may address a client’s motivation to change, provide incentives for abstinence, build skills to resist drug use, replace substance-using activities with constructive and rewarding activities, improve problem-solving skills, and facilitate interpersonal relationships. Treatment may take at least three months, and best outcomes occur with the longest treatment. Contingency management gives tangible rewards such as a food or movie voucher to individuals to support positive behavior change.

- Twelve-step programs, such as Alcoholics Anonymous (AA) or Narcotics Anonymous (NA), run by peers with similar issues.

- Recovery support services for individuals during and after treatment for SUD. These services are delivered by trained individuals and focus on providing assistance in navigating systems of care, removing barriers to recovery, staying engaged in the recovery process, and providing a social context for individuals to engage in community living without substance use. Support is provided in the educational setting for high school and college-aged clients who need help while surrounded by a culture of substance use by their peers in these settings.

Avoiding Stigma: Words Matter

Health care professionals must pay attention to the language they use when discussing substance use to help clients heal from SUD. Stigma is a negative impression associated with certain conditions such as SUD. Stigma interferes with clients admitting to substance misuse and pursuing treatment. Clinicians can reduce stigma while discussing SUD by discussing it as a chronic, treatable brain disease rather than a moral failing. It is also important to use “person-first language,” including phrases such as “a person with substance use disorder” instead of words like “addict,” “alcoholic,” “drunk,” or “substance abuser” to verbally indicate the client is more than just their disease.[52]

Nursing Assessments and Interventions for Clients Suspected of Substance Misuse

Assessment (Recognizing Cues)

Nurses may recognize signs and symptoms of substance misuse as described by a client, their significant others, or family members. Nurses who recognize cues of a potential misuse or substance use disorder based on DSM-5-TR criteria should notify the health care provider for follow-up assessment, diagnosis, and treatment. DSM-5-TR criteria are discussed under the “Substance Use Disorders” subsection.

Nurses may also be involved in screening for substance use disorders during admission assessments using standardized tools. An example of a cost-effective screening tool for alcohol use disorder is the Single Alcohol Screening Question (SASQ) that asks clients the following question:

- “How many times in the past year have you had (four for women or five for men) or more drinks in a day?”

Note that the SASQ question is not asked as a “Yes” or “No” question. One DSM-5-TR criterion for AUD is alcohol used in larger amounts or over a longer period than intended. If the client indicates one or more times, additional assessment regarding potential symptoms of AUD is performed, and the health care provider is notified.

Diagnostic Testing

Diagnostic tests like blood, urine, and hair tests may be ordered by a health care provider to assess for the presence of substances.

Nursing Interventions

Stress Management and Healthy Coping Strategies

Nurses teach stress management techniques and promote healthy coping strategies as part of the recovery process. Review “Stress and Coping” and “Applying the Nursing Process and Clinical Judgment Model to Promote Healthy Coping” in the “Mental Health Concepts” chapter.

Preventing Substance Use Disorders

Nurses are involved in providing prevention interventions for SUD at many levels, including individual, family, school, and community levels. Prevention interventions focus on protective factors to help prevent substance use disorders from developing despite the presence of risk factors.

Examples of interventions to promote protective factors at the individual level include the following[53]:

- Social, emotional, and behavioral competence: Promoting interpersonal skills that help youth integrate feelings, thoughts, and actions to achieve specific social and interpersonal goals.

- Self-efficacy: Enhancing an individual’s belief that they can modify, control, or abstain from substance use.

- Spirituality: Supporting beliefs in a higher being or involvement in spiritual practices or religious activities.

- Resiliency: Encouraging an individual’s capacity for adapting to change and coping with stressful events in healthy and flexible ways.

Interventions to promote protective factors at the family, school, and community levels are as follows[54]:

- Providing opportunities for positive social involvement.

- Recognizing positive behavior.

- Bonding by promoting attachment, commitment, and positive communication with family members, schools, and communities.

- Encouraging committed relationships with people who do not misuse alcohol or drugs.

- Establishing family, school, and community norms that communicate healthy beliefs and clear and consistent expectations about not misusing alcohol or drugs.

Substance Use Disorder in Nurses

Health care professionals are not immune to developing SUD. Long working hours, multiple exposures to traumatic situations, chronic stress, and work-related musculoskeletal injuries that cause chronic pain put them at risk. Nurses also have access to controlled substances when administering prescribed medications, further adding to their risk.[55]

The National Council of State Boards of Nursing (NCSBN) states many nurses with substance use disorder (SUD) are unidentified, untreated, and continue to practice when their impairment may endanger the lives of their clients. Because of the potential safety hazards to clients, it is a nurse’s legal and ethical responsibility to report a colleague’s suspected SUD to their manager or supervisor. This reporting contributes to early detection and, hopefully, early treatment.[56]

While it can be hard to differentiate between the subtle signs of SUD and stress-related behaviors, nurses can be aware of three significant signs of SUD, which include behavioral changes, physical signs, and drug diversion[57]:

- Behavioral changes: Decreased job performance, absences from the unit for extended periods, frequent trips to the bathroom, arriving late or leaving early, and making an excessive number of mistakes, including medication errors. These behaviors may show the nurse is using substances before or during work.

- Physical signs: Subtle changes in appearance that may escalate over time, increasing isolation from colleagues, inappropriate verbal or emotional responses, diminished alertness, confusion, or memory lapses.

- Drug diversion: Medication is misdirected from intended client use to personal use, sale, or distribution to others. Diversion includes drug theft, drug use, or tampering with medications (e.g., adulteration or substitution). Drug diversion is a felony that can result in a nurse’s criminal prosecution and loss of license. Signs of diversion include frequent discrepancies in opioid counts, unusual amounts of opioid wastage, numerous corrections of medication records, frequent reports of ineffective pain relief from clients, offers to medicate coworkers’ clients for pain, and altered verbal or phone medication orders.

The earlier a nurse is diagnosed with SUD and treatment is initiated, the sooner client safety is protected and the better the chances for the nurse to recover and return to work. In most states, a nurse diagnosed with a SUD enters a nondisciplinary program designed by the Board of Nursing for treatment and recovery services. When a colleague treated for an SUD returns to work, nurses should create a supportive environment that encourages their continued recovery.[58]

View the NCSBN PDF pamphlet called A Nurse’s Guide to Substance Use Disorder in Nursing.

View this supplementary YouTube video[59] from NCSBN regarding SUD in nursing: Substance Use Disorder in Nursing.

Preventing Drug Diversion

All nurses perform common procedures based on agency policy to help prevent drug diversion. For example, if a client is receiving patient-controlled anesthesia (PCA), the PCA pump is locked and at shift change, two nurses verify and document the amount of medication administered, as well as the amount of medication remaining. Another example is when controlled substances are kept in a locked medication cart. At the end of the shift, two nurses verify and document the doses administered during the shift and the doses remaining in the cart. In both of these examples, if there are any discrepancies, the nursing supervisor is notified and an investigation regarding possible diversion is performed. A third example of a procedure to prevent drug diversion is related to drug wasting of controlled substances. If a nurse only administers a partial dose from a package or vial of a controlled substance to a client, two nurses observe and document the disposal of the remaining medication. The second nurse must actually witness the disposal of the medication in a way that is not retrievable (such as down the sink) according to agency policy. If the second nurse does not visually witness the disposal of medication, they should decline cosigning the medication waste.[60]

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (US). (n.d.). Facing addiction in America. National Center for Biotechnology Information. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK424857/ ↵

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. (2023). SAMHSA announces National Survey on Drug Use and Health (NSDUH) results detailing mental illness and substance use levels in 2021. https://www.hhs.gov/about/news/2023/01/04/samhsa-announces-national-survey-drug-use-health-results-detailing-mental-illness-substance-use-levels-2021.html ↵

- American Addiction Centers. (2024). Health risks of substance abuse. https://americanaddictioncenters.org/health-complications-addiction ↵

- Herdman, T. H., Kamitsuru, S., & Lopes, C. (Eds.). (2024). Nursing diagnoses: Definitions & classification, 2024-2026. Thieme. ↵

- Herdman, T. H., Kamitsuru, S., & Lopes, C. (Eds.). (2024). Nursing diagnoses: Definitions & classification, 2024-2026. Thieme. ↵

- American Psychiatric Association. (2022). Desk reference to the diagnostic criteria from DSM-5-TR (5th ed.). American Psychiatric Association Publishing. ↵

- American Psychiatric Association. (2022). Desk reference to the diagnostic criteria from DSM-5-TR (5th ed.). American Psychiatric Association Publishing. ↵

- American Psychiatric Association. (2022). Desk reference to the diagnostic criteria from DSM-5-TR (5th ed.). American Psychiatric Association Publishing. ↵

- American Psychiatric Association. (2022). Desk reference to the diagnostic criteria from DSM-5-TR (5th ed.). American Psychiatric Association Publishing. ↵

- Ernstmeyer, K., & Christman, E. (Eds.). (2022). Nursing: Mental health and community concepts. https://wtcs.pressbooks.pub/nursingmhcc/ ↵

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (US). (n.d.). Facing addiction in America. National Center for Biotechnology Information. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK424857/ ↵

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (US). (n.d.). Facing addiction in America. National Center for Biotechnology Information. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK424857/ ↵

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (US). (n.d.). Facing addiction in America. National Center for Biotechnology Information. Used under Fair Use. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK424849/figure/ch2.f3/ ↵

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (US). (n.d.). Facing addiction in America. National Center for Biotechnology Information. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK424857/ ↵

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (US). (n.d.). Facing addiction in America. National Center for Biotechnology Information. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK424857/ ↵

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (US). (n.d.). Facing addiction in America. National Center for Biotechnology Information. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK424857/ ↵

- Ernstmeyer, K., & Christman, E. (Eds.). (2022). Nursing: Mental health and community concepts. https://wtcs.pressbooks.pub/nursingmhcc/ ↵

- Stellern, J., Xiao, K. B., Grennell, E., Sanches, M., Gowin, J. L., & Sloan, M. E. (2022). Emotion regulation in substance use disorders: A systematic review and meta‐analysis. Addiction, 118(1), 30–47. https://doi.org/10.1111/add.16001 ↵

- Office of the Assistant Secretary for Health. (2024). Drink alcohol only in moderation. https://health.gov/myhealthfinder/health-conditions/heart-health/drink-alcohol-only-moderation ↵

- “NIH_standard_drink_comparison.jpg” by National Institutes of Health is in the Public Domain. ↵

- American Psychiatric Association. (2022). Desk reference to the diagnostic criteria from DSM-5-TR (5th ed.). American Psychiatric Association Publishing. ↵

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (n.d.). About underage drinking. https://www.cdc.gov/alcohol/underage-drinking/ ↵

- National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism. (2024). Understanding binge drinking. https://www.niaaa.nih.gov/publications/brochures-and-fact-sheets/binge-drinking ↵

- National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism. (n.d.). Alcohol’s effects on health. https://www.niaaa.nih.gov/alcohols-effects-health ↵

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. (2024). Know the risks of marijuana. https://www.samhsa.gov/marijuana ↵

- American Psychiatric Association. (2022). Desk reference to the diagnostic criteria from DSM-5-TR (5th ed.). American Psychiatric Association Publishing. ↵

- Dydyk, A. M. (2024). Opioid use disorder. StatPearls. [Internet]. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK553166/ ↵

- American Psychiatric Association. (2022). Desk reference to the diagnostic criteria from DSM-5-TR (5th ed.). American Psychiatric Association Publishing. ↵

- Dydyk, A. M. (2024). Opioid use disorder. StatPearls. [Internet]. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK553166/ ↵

- Dowell, D., Ragan, K. R., Jones, C. M., Baldwin, G. T., & Chou, R. (2022). CDC clinical practice guideline for prescribing opioids for pain - United States, 2022. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 71(3), 1-95. https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/volumes/71/rr/rr7103a1.htm?s_cid=rr7103a1_w ↵

- American Psychiatric Association. (2022). Desk reference to the diagnostic criteria from DSM-5-TR (5th ed.). American Psychiatric Association Publishing. ↵

- American Psychiatric Association. (2022). Desk reference to the diagnostic criteria from DSM-5-TR (5th ed.). American Psychiatric Association Publishing. ↵

- Penn Foundation. (n.d.). Addiction is a family disease. https://www.pennfoundation.org/news-events/articles-of-interest/addiction-is-a-family-disease/ ↵

- Gould, W. R. (2024). How to spot the signs of codependency. Verywell Mind. https://www.verywellmind.com/what-is-codependency-5072124 ↵

- Mental Health America. (n.d.). Co-dependency. https://www.mhanational.org/co-dependency ↵

- Gould, W. R. (2024). How to spot the signs of codependency. Verywell Mind. https://www.verywellmind.com/what-is-codependency-5072124 ↵

- Mental Health America. (n.d.). Co-dependency. https://www.mhanational.org/co-dependency ↵

- Gould, W. R. (2024). How to spot the signs of codependency. Verywell Mind. https://www.verywellmind.com/what-is-codependency-5072124 ↵

- Gould, W. R. (2024). How to spot the signs of codependency. Verywell Mind. https://www.verywellmind.com/what-is-codependency-5072124 ↵

- Mental Health America. (n.d.). Co-dependency. https://www.mhanational.org/co-dependency ↵

- Face It Together. (n.d.). Common myths about addiction. https://www.wefaceittogether.org/learn/common-myths ↵

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. (2021). Key substance use and mental health indicators in the United States: Results from the 2020 National Survey on Drug Use and Health. [PDF]. https://www.samhsa.gov/data/sites/default/files/reports/rpt35325/NSDUHFFRPDFWHTMLFiles2020/2020NSDUHFFR1PDFW102121.pdf ↵

- Herdman, T. H., Kamitsuru, S., & Lopes, C. (Eds.). (2024). Nursing diagnoses: Definitions & classification, 2024-2026. Thieme. ↵

- Kitzinger, R. H., Gardner, J. A., Moran, M., Celkos, C., Fasano, N., Linares, E., Muthee, J., & Royzner, G. (2023). Habits and routines of adults in early recovery from substance use disorder: Clinical and research implications from a mixed methodology exploratory study. Substance Abuse: Research and Treatment, 17. https://doi.org/10.1177/11782218231153843 ↵

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. (2021). Key substance use and mental health indicators in the United States: Results from the 2020 National Survey on Drug Use and Health. [PDF]. https://www.samhsa.gov/data/sites/default/files/reports/rpt35325/NSDUHFFRPDFWHTMLFiles2020/2020NSDUHFFR1PDFW102121.pdf ↵

- Herdman, T. H., Kamitsuru, S., & Lopes, C. (Eds.). (2024). Nursing diagnoses: Definitions & classification, 2024-2026. Thieme. ↵

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. (2024). Medications for substance use disorders. https://www.samhsa.gov/medications-substance-use-disorders ↵

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration and National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism. (2015). Medication for the treatment of alcohol use disorder: A brief guide. [PDF]. https://store.samhsa.gov/sites/default/files/sma15-4907.pdf ↵

- Holland, K. (2018). Medication for alcoholism. Healthline. https://www.healthline.com/health/medication-alcoholism ↵

- Sevarino, K. A. (2023). Opioid withdrawal: Medically supervised withdrawal during treatment for opioid use disorder. UpToDate. https://www.uptodate.com ↵

- Ernstmeyer, K., & Christman, E. (Eds.). (2022). Nursing: Mental health and community concepts. https://wtcs.pressbooks.pub/nursingmhcc/ ↵

- National Institute on Drug Abuse. (2021). Words matter - Terms to use and avoid when talking about addiction. https://nida.nih.gov/nidamed-medical-health-professionals/health-professions-education/words-matter-terms-to-use-avoid-when-talking-about-addiction ↵

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (US). (n.d.). Facing addiction in America. National Center for Biotechnology Information. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK424857/ ↵

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (US). (n.d.). Facing addiction in America. National Center for Biotechnology Information. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK424857/ ↵

- American Addiction Centers. (2024). Statistics for substance abuse in medical professionals. https://americanaddictioncenters.org/addiction-statistics/medical-professionals ↵

- National Council of State Boards of Nursing. (2018). A nurse’s guide to substance use disorder in nursing. [PDF]. https://www.ncsbn.org/public-files/SUD_Brochure_2014.pdf ↵

- National Council of State Boards of Nursing. (2018). A nurse’s guide to substance use disorder in nursing. [PDF]. https://www.ncsbn.org/public-files/SUD_Brochure_2014.pdf ↵

- National Council of State Boards of Nursing. (2018). A nurse’s guide to substance use disorder in nursing. [PDF]. https://www.ncsbn.org/public-files/SUD_Brochure_2014.pdf ↵

- NCSBN. (2020, May 28). Substance use disorder in nursing [Video]. YouTube. All rights reserved. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=fHbfza_6_Lg ↵

- Breve, F., LeQuang, J. A. K., & Batastini, L. (2022). Controlled substance waste: Concerns, controversies, solutions. Cureus, 14(2). https://www.cureus.com/articles/78322-controlled-substance-waste-concerns-controversies-solutions#!/ ↵

The use of alcohol or drugs in a manner, situation, amount, or frequency that could cause harm to the user or to those around them.

A problematic pattern of substance use leading to clinically significant impairment.

A need for markedly increased amounts of the substance to achieve intoxication or the desired effect and a diminished effect with continued use of the same amount of the substance.

No SUD criteria have been met for three months (or 12 months).

No criteria have been met for 12 months or longer.

Progressive changes in the structure and function of the brain.

The stage at which an individual consumes an intoxicating substance and experiences its rewarding or pleasurable effects.

The stage at which an individual experiences a negative emotional state in the absence of the substance.

The stage at which one seeks substances again after a period of abstinence.

Signs and symptoms may include slurred speech, incoordination, unsteady gait, nystagmus, impaired attention or memory, and stupor or coma during or after the consumption of alcohol.

When females drink four or more drinks per two-hour session and males drink five or more drinks in a two-hour session.

The most common SUD in the United States, including use by children and adolescents. It cocucrs with the sustained excessive use of alcohol.

Includes two or more of the following signs or symptoms conjuntival erythema, increased appetite, dry mouth, and tachycardia developing within two hours after cannabis use.

A substance found in certain prescription pain medications and illegal drugs like heroin.

Refers to the chronic use of opioids that causes clinically significant distress or impairment.

Includes pupillary constriction, drowsiness, slurred speech, and impaired attention or memory during or shortly after opioid use.

A condition in which gambling becomes an addiction and interferes with a person's daily life.

A dysfunctional relationship pattern in which impacts a person who is affeted by another person's substance misuse.

Codependent person assists the client with SUD more than they should.

Completing activities that should be the responsibility of someone else.

When individuals with substance use disorder overcome their disorder with effective treatment and regain health and social function.

A process of change through which individuals improve their health and wellness, live a self-directed life, and strive to reach their full potential.

Occurs when an individual returns to the former problematic behavior, such as smoking, drinking excessively, or misusing other substances.

A negative impression associated with certain conditions such as SUD.