6.3 Intimate Partner Violence

Intimate partner violence (IPV), also called domestic violence, refers to abuse or aggression that occurs in a romantic relationship with a current or former spouse or dating partner. IPV is a significant public health problem in the United States, with about 41% of women and 26% of men reporting an impact related to physical violence, sexual violence, or stalking by an intimate partner during their lifetime.[1]

IPV often results in injuries and death. Data from U.S. crime reports suggest that about one in five homicide victims are killed by an intimate partner and over half of female homicide victims are killed by a current or former male intimate partner.[2] Many other negative health outcomes are associated with intimate partner violence, including acute and chronic physical and mental health problems. Survivors may experience depression and post-traumatic stress disorder symptoms and are at higher risk for suicide or engaging in behaviors such as smoking, binge drinking, and risky sexual activity. People from marginalized racial and ethnic minority groups are at higher risk for worse consequences.[3]

IPV can vary in how often it happens and how severe it is. IPV can include any of the following types of behaviors[4]:

- Physical violence: Hurting or attempting to hurt a partner by hitting, kicking, or using another type of physical force

- Sexual violence: Forcing or attempting to force a partner to take part in a sex act, sexual touching, or a nonphysical sexual event (e.g., sexting) when the partner does not or cannot consent

- Stalking: A pattern of repeated, unwanted attention and contact by a partner that causes fear or concern for one’s own safety or the safety of someone close to the victim

- Psychological aggression: The use of verbal and/or nonverbal communication with the intent to harm another partner mentally or emotionally and/or to exert control over another partner

View the following CDC YouTube video[5] on intimate partner violence: What is Intimate Partner Violence?

Duluth Model and the Power and Control Wheel

The root of IPV is one person exerting power and control over another person. Males or females can be perpetrators or victims. The Power and Control Wheel was developed by the Domestic Abuse Intervention Programs in Duluth, Minnesota, and based on research using focus groups of women who had experienced battering. The most common abusive behaviors or tactics used against these women were documented in the Power and Control Wheel. “Power and Control” are in the center of the wheel, and abusive behaviors are the spokes of the wheel and include tactics such as threats, intimidation, and coercion. This wheel contains gender-specific language because it based on research using focus groups of battered women.

Conversely, the Equality Wheel demonstrates behaviors that occur in healthy relationships. This wheel contains gender-specific language because it based on research using focus groups of battered women. The information in this wheel can be used by nurses to teach clients about nonviolent partnerships.

Although these wheels were developed based on research about battered women, the concepts can be used to identify and explore abuse across all genders and encourage non-violent change. The Duluth Model is an innovative, community-based program addressing intimate partner violence that encourages law enforcement, family law, and social work agencies to work together to reduce violence against women and rehabilitate perpetrators of domestic violence.[6]

Read more about the Duluth Model and view the Power and Control Wheel and Equity Wheel at Wheel Information Center.

Cycle of Violence

Domestic violence has been traditionally described as a cycle of violence, which consists of a calm phase, a tension-building phase, an altercation, and a reconciliation phase. In the calm phase, the relationship is peaceful. In the tension-building phase, there may be repeated minor alterations with a calm phase between instances. During an altercation phase, an event occurs, which can include yelling, belittling, and/or physical violence. After the altercation phase, there may be a reconciliation phase. However, although there may be patterns that occur in an abusive relationship, abuse is not predictable. In fact, describing abuse as a cycle becomes problematic when this language is used against victims, particularly in a court setting. For example, an attorney might infer, “Why didn’t you leave during the calm stage?” The fault lies with the abuser, not the victim, so it is important to not use language that blames the person experiencing abuse. Instead, the Power and Control Wheel explains the many tactics an abusive partner uses to establish and maintain power and control over their partner.[7]

View a supplementary YouTube video[8] about the Power and Control Wheel and the Cycle of Violence at Power & Control Wheel & Cycle of Violence – English.

IPV can happen to anyone. It occurs in all races, religions, income, and educational levels. Observers often wonder why a person experiencing IPV does not leave the relationship. The Power and Control Wheel provides many factors impacting the person’s decision. Additionally, the risk of homicide for a person ending an abusive relationship should not be taken lightly. For one person’s story about domestic violence, view the video in the following box.

View the following supplementary YouTube video[9] by Leslie Morgan Steiner: Why Domestic Violence Victims Don’t Leave | Leslie Morgan Steiner | TED.

Cultural Considerations

IPV may manifest or be received differently depending on the person’s cultural values and beliefs. Cultural context can also play a large role in a survivor’s decision to stay or leave an abusive relationship.

Read more about abuse in a variety of cultural communities in the National Domestic Violence Hotline web page “Abuse and Cultural Context.”

Teen Dating Violence

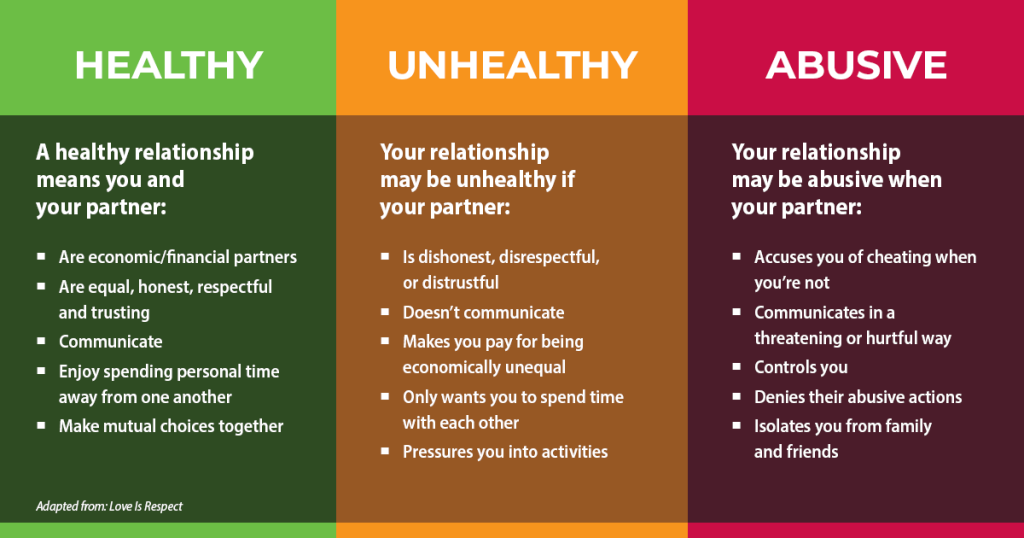

When IPV occurs during adolescence, it is referred to as teen dating violence. Teen dating violence affects millions of U.S. teens each year. Youth from marginalized groups, such as the LGBTQ+ population, are at greatest risk of experiencing sexual and physical dating violence. The use of alcohol and drugs is also a risk factor for nonconsensual sexual contact among undergraduate and graduate students.[10] See Figure 6.2[11] for an infographic that can be used to teach about healthy relationships.

Preventing IPV

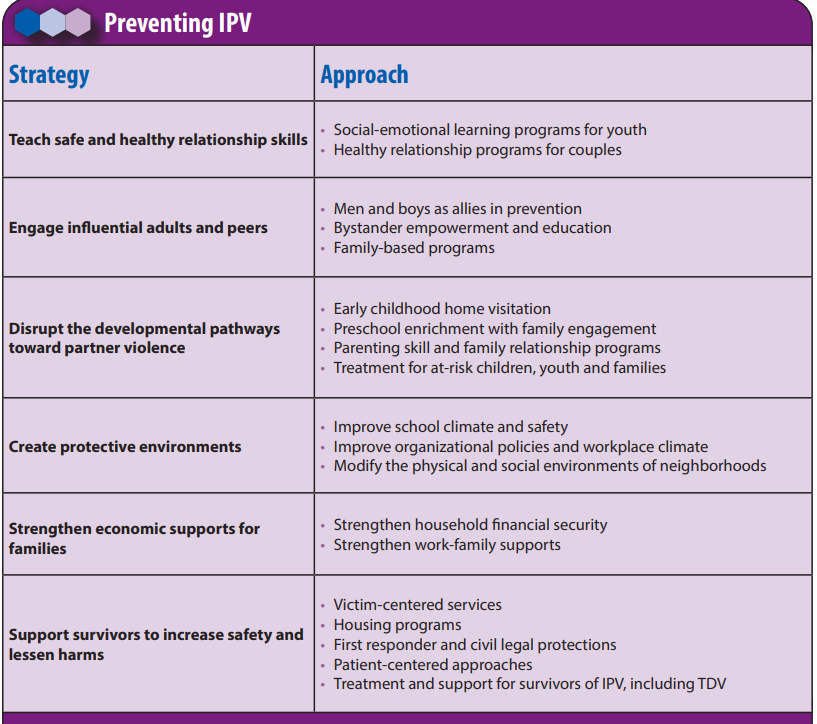

Nurses and communities can promote healthy, respectful, and nonviolent relationships to help reduce the occurrence of IPV.[12] See Figure 6.3[13] for an infographic related to IPV prevention strategies from the CDC.

Applying the Nursing Process to IPV

Nurses are crucial in recognizing warning signs of IPV, collecting additional information, and implementing interventions like safety plans.

Assessment

Recognizing Cues

The following observations should heighten a nurse’s suspicion of IPV[14]:

- Inconsistent explanation of injuries.

- Delay in seeking treatment for injuries.

- Frequent emergency department or urgent care visits. (Abusers typically do not want their victims to form an ongoing care relationship with one clinician. They may feel the victim will be less likely to find an ally in an emergency department where care may be more fragmented.)

- Missed appointments. The client may not keep appointments because the abuser will not allow medical attention.

- Late initiation of prenatal care during pregnancy.

- Repeated abortions. Unplanned pregnancy may result from sexual assault and/or not being allowed to use birth control by the abuser.

- Medication nonadherence. Victims may not take medicines because the abuser has taken them away or not allowed the partner to fill prescriptions.

- Inappropriate affect. Victims may appear jumpy, fearful, or cry readily. They may avoid eye contact and seem evasive or hostile. Additionally, flat affect or dissociation may suggest post-traumatic stress disorder.

- Overly attentive or verbally abusive partner. The clinician should be suspicious if the partner answers questions for the client. If the partner refuses to leave the examination room, the nurse should find a way to get the partner to leave before questioning the client.

- Apparent social isolation.

- Reluctance to undress or have a genital, rectal, or oral examination or difficulty undergoing these or other examinations.

Nursing Interview

If a nurse recognizes cues of suspected IPV, the nurse must ensure that the client feels safe and comfortable for follow-up questioning. Individuals are more likely to disclose their experiences of IPV when the nurse uses the following strategies[15]:

- Provide privacy. Other people present in the room should be asked to leave for the interview and examination. Resistance of a partner to leave is a warning sign.

- Appear concerned with good eye contact.

- Be nonjudgmental and compassionate.

- Use open-ended questioning and ask only a few questions.

- Ask about “being hurt” or “treated badly” and avoid phrases like “domestic violence,” “victim,” “abused,” or “battered.”

- Assure confidentiality unless mandatory reporting is required or someone is in grave danger (i.e., duty to warn).

- Do not pressure to disclose, leave the relationship, or press charges.

- Encourage shared decision-making and respect for the client’s decisions.

Physical Examination

A physical examination can provide warning signs that abuse may be occurring. Any injury without a good explanation, particularly involving the head and neck, teeth, or genital area, should raise suspicion. Typically, victims of domestic violence present with injuries on the central part of the body such as the breasts, abdomen, and genitals. Wounds on the head and neck, particularly neck bruising, may be caused by attempted strangulation. Wounds on the forearms often occur when a victim is in a defensive position. Bruises of different ages may be present due to repeated abuse. There may be other evidence of sexual assault, including sexually transmitted infections or unintended pregnancy.[16]

People experiencing abuse may deny the abuse for several reasons. They may not feel safe disclosing information, especially if questions are not asked in a private environment or there is a fear of information not being kept confidential. They may not be emotionally ready to admit the reality of the situation, they may blame themselves, or they may feel like a failure if they admit to being abused. They may fear rejection, feel ashamed, believe that the abuse will not happen again, fear reprisal by the abuser, believe that they have no alternatives, or lack knowledge of resources that could help them. There may be language or cultural barriers between nurses and clients that interfere with communication or discomfort with using an interpreter to discuss sensitive issues.[17]

Clients for whom IPV is suspected but is not acknowledged should be asked again at subsequent visits. Research indicates clients are more likely to disclose information after they have been asked about IPV repeatedly in the health care setting and it is “normalized,” meaning it happens frequently to many people.[18]

SAFE Survey

The Joint Commission recommends that hospitals use criteria to identify possible victims of abuse and neglect upon hospital entry and on an ongoing basis, educate staff about how to recognize signs of abuse, assist with referrals of possible victims, and report abuse in accordance with law and regulation.

Several IPV screening tools have been studied for use in emergency departments and clinics. SAFE is an example of a short survey tool that stands for the following assessments[19],[20]:

- S: Stress/Safety: Do you feel safe in your relationship?

- A: Afraid/Abused: Have you ever been in a relationship where you were threatened, hurt, or afraid?

- F: Friends/Family: Are your friends or family aware you have been hurt?

- E: Emergency Plan: Do you have a safe place to go and the resources you need in an emergency?

Nursing Interventions

Survivors of IPV are often afraid to leave their abusive partners because of the threats that have been made against them or their loved ones. Safety is a top priority when IPV is identified. Before the client leaves the office, referrals to local resources should be made and a personalized safety plan in place. The most dangerous time in an abusive relationship occurs when the abused person decides to leave. Separation is a common theme found in spousal murder-suicide where half of the cases occur after the couple have either separated (26%), were in the process of separating (9%), or had expressed a desire to separate (15%).[21] As the abuser realizes they are losing power and control over their partner, they often escalate tactics to increase fear in the individual leaving the relationship in an effort to make the individual stay.[22]

A safety plan is a set of actions that can help lower the risk of a person being hurt by an abusive partner. It includes specific information and resources that will increase safety at school, home, and other places visited regularly. View an infographic related to a safety plan in Figure 6.4.[23]

Nurses should guide clients experiencing IPV to create a personalized online safety plan and review additional resources at the National Domestic Violence Hotline. These resources are provided in the following box.

If you need help or know someone who is experiencing IPV, visit the National Domestic Violence Hotline or call 1-800-799-7233.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (n.d.). About intimate partner violence. https://www.cdc.gov/intimate-partner-violence/about/ ↵

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (n.d.). About intimate partner violence. https://www.cdc.gov/intimate-partner-violence/about/ ↵

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (n.d.). About intimate partner violence. https://www.cdc.gov/intimate-partner-violence/about/ ↵

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (n.d.). About intimate partner violence. https://www.cdc.gov/intimate-partner-violence/about/ ↵

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2018, May 15). What is intimate partner violence? [Video]. YouTube. All rights reserved. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=VuMCzU54334 ↵

- Domestic Abuse Intervention Programs. (n.d.). Wheel information center. https://www.theduluthmodel.org/wheels/ ↵

- National Domestic Violence Hotline. (n.d.). Is abuse really a “cycle”? https://www.thehotline.org/resources/is-abuse-really-a-cycle/ ↵

- Metro Nashville Office of Family Safety. (2022, March 8). Power & Control Wheel & Cycle of Violence - English [Video]. YouTube. All rights reserved. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ZX5ijOq3mTU ↵

- TED. (2013, January 25). Why domestic violence victims don't leave | Leslie Morgan Steiner | TED [Video]. YouTube. All rights reserved. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=V1yW5IsnSjo ↵

- Weil, A. (2022). Intimate partner violence: Diagnosis and screening. UpToDate. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/intimate-partner-violence-diagnosis-and-screening ↵

- “teen-dating-violence-relationship-range-chart-graphic.png” by unknown author for FairFax County Department of Family Services, Domestic and Violent Services is used under Fair Use. Access for free at https://www.fairfaxcounty.gov/familyservices/domestic-sexual-violence/teen-dating-violence ↵

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (n.d.). About intimate partner violence. https://www.cdc.gov/intimate-partner-violence/about/ ↵

- “Preventing IPV” in “Preventing Intimate Partner Violence Prevention Resource For Action PDF” by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention is in the Public Domain. ↵

- Weil, A. (2022). Intimate partner violence: Diagnosis and screening. UpToDate. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/intimate-partner-violence-diagnosis-and-screening ↵

- Weil, A. (2022). Intimate partner violence: Diagnosis and screening. UpToDate. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/intimate-partner-violence-diagnosis-and-screening ↵

- Weil, A. (2022). Intimate partner violence: Diagnosis and screening. UpToDate. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/intimate-partner-violence-diagnosis-and-screening ↵

- Weil, A. (2022). Intimate partner violence: Diagnosis and screening. UpToDate. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/intimate-partner-violence-diagnosis-and-screening ↵

- Weil, A. (2022). Intimate partner violence: Diagnosis and screening. UpToDate. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/intimate-partner-violence-diagnosis-and-screening ↵

- Weil, A. (2022). Intimate partner violence: Diagnosis and screening. UpToDate. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/intimate-partner-violence-diagnosis-and-screening ↵

- Rabin, R. F., Jennings, J. M., Campbell, J. C., & Bair-Merritt, M. H. (2009). Intimate partner violence screening tools. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 36(5). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2009.01.024 ↵

- Battered Women’s Support Services. (2020). Eighteen months after leaving domestic violence is still the most dangerous time. https://www.bwss.org/eighteen-months-after-leaving-domestic-violence-is-still-the-most-dangerous-time/ ↵

- Battered Women’s Support Services. (2020). Eighteen months after leaving domestic violence is still the most dangerous time. https://www.bwss.org/eighteen-months-after-leaving-domestic-violence-is-still-the-most-dangerous-time/ ↵

- “Protecting Yourself and Your Children” by unknown author for World Health Organization is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO. Access for free at https://www.who.int/multi-media/details/make-a-safety-plan-for-you-and-your-children ↵

Abuse or aggression that occurs in a romantic relationship with a current or former spouse or dating partner. Also referred to an domestic violence.

Abuse or aggression that occurs in a romantic relationship with a current or former spouse or dating partner. Also referred to as initimate partner violence.

Hurting or attempting to hurt a partner by hitting, kicking, or using another type of physical force.

Forcing or attempting to force a partner to take part in a sex act, sexual touching, or a nonphysical sexual event (e.g., sexting) when the partner does not or cannot consent.

A pattern of repeated, unwanted attention and contact by a partner that causes fear or concern for one’s own safety or the safety of someone close to the victim.

The use of verbal and/or nonverbal communication with the intent to harm another partner mentally or emotionally and/or to exert control over another partner.

An innovative, community-based program addressing intimate partner violence that encourages law enforcement, family law, and social work agencies to work together to reduce violence against women and rehabilitate perpetrators of domestic violence.

Description of domestic violence which consists of a calm phase, a tension-building phase, an altercation, and a reconciliation phase.

IPV occurs during adolescence.

A set of actions that can help lower the risk of a person being hurt by an abusive partner.