5.2 Basic Concepts of Mental Health and Mental Illness

Mental Health and Resilience

Mental health is an essential component of health.[1]

The World Health Organization (WHO) defines health as a state of complete physical, mental, and social well-being and not merely the absence of disease or infirmity.[2]

Resilience refers to an individual successfully adapting to difficult or challenging life experiences through mental, emotional, and behavioral flexibility and adjustment to external and internal demands. Several factors contribute to a person’s resiliency, including the ways they view and engage with the world, the availability of quality social resources, and specific coping strategies. According to the American Psychological Association, research demonstrates that the resources and skills associated with resilience can be cultivated and practiced.[3]

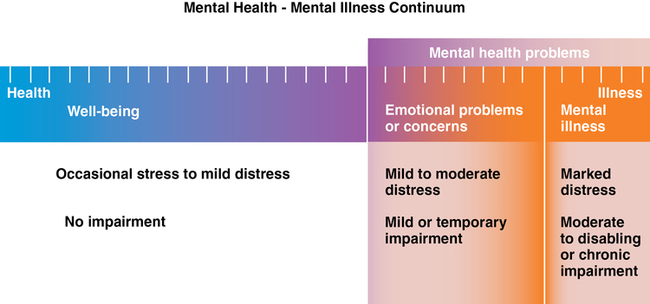

Mental health fluctuates over the course of an individual’s life span and can range from well-being with occasional stress and mild distress to mental health problems with emotional problems and/or mental illness with impaired functioning, as indicated on the mental health continuum illustrated in Figure 5.1.[4]

Mental Illness

According to the American Psychiatric Association, mental illness is a health condition involving changes in emotion, thinking, behavior, or a combination of these, associated with emotional distress and problems functioning in social, work, or family activities. Poor mental health increases the risk of chronic physical illnesses, such as heart disease, cancer, and strokes, and can lead to thoughts and intentions of suicide or self-harm. The term mental health conditions is also used to encompass mental health disorders, psychosocial disabilities, and other mental states with significant distress, impaired functioning, or risk of self-harm.[5]

Mental illness is common in the United States, with more than 1 in 5 adults having a diagnosable mental disorder.[6] Mental illness can affect anyone regardless of age, gender, socioeconomic status, ethnicity, religion/spirituality, or sexual orientation. It can occur at any age, but symptoms of 75% of mental illnesses begin by age 24.[7]

Mental illnesses take many forms. Some are mild and only interfere in limited ways with daily life, such as some phobias (abnormal fears). Other mental health conditions are so severe that the person requires care in a hospital. Suicidal ideation and self-harming behaviors are common symptoms associated with mental illness. Suicidal ideation refers to thinking about or formulating plans for suicide. Self-harm refers to purposely injuring one’s body, such as cutting oneself with a sharp object. Similar to other medical illnesses, treatment depends on the illness and the severity of its impact on the person’s functioning. The majority of individuals with treated mental illnesses are able to continue to function in their daily lives.[8]

The symptoms of mental illnesses cluster into discrete mental health disorders defined by the American Psychiatric Association in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th edition, Text Revision (DSM-5-TR). For example, depressive disorders, bipolar disorder, anxiety disorders, and many other disorders are defined in the DSM-5-TR with specific signs and symptoms.[9]

Read more information about specific mental health disorders in the “Mental Health Conditions” chapter.

Cultural Considerations

An individual’s cultural values, beliefs, and perspectives impact how they view health and illness. In the case of mental illness, culture can impact how an individual describes symptoms, whether or not they seek help, the type of help they seek, and the social support available. For example, individuals from some cultures may express symptoms of distress through one or more physical (somatic) symptoms, such as dizziness, while not reporting their emotional symptoms. However, if questioned further, they may acknowledge having emotional symptoms.[10]

Cultural perspectives also impact the meaning of illness, if it relates to the body or the mind (or both), if it warrants sympathy, how much stigma surrounds it, what might cause it, and what type of person might develop it. Cultural meanings of illness have significant consequences in terms of whether people are motivated to seek treatment, how they cope with their symptoms, and the support they receive from their families and communities. In general, historically marginalized communities in the United States are less likely to access mental health treatment or may wait until symptoms are severe before seeking assistance.[11]

View a supplementary YouTube TED Talk video[12] about cultural stigma affecting mental health: There’s No Shame in Taking Care of Your Mental Health | Sangu Delle.

Early Signs of Mental Health Conditions

Nurses in all health care settings interact with individuals who have diagnosed and undiagnosed emotional and mental health conditions. When nurses recognize signs and symptoms of mental health conditions, they can react appropriately and request the provider refer clients to services. Each mental health disorder has specific signs and symptoms, which are covered in the “Mental Health Conditions” chapter. Common signs of mental health problems in adults and adolescents are as follows:

- Excessive worrying or fear

- Excessive sad or low feelings

- Confused thinking or problems concentrating and learning

- Extreme mood changes, including uncontrollable “highs” or feelings of euphoria

- Prolonged or strong feelings of irritability or anger

- Avoidance of friends and social activities

- Difficulty understanding or relating to other people

- Changes in sleeping habits or feeling tired and low energy

- Changes in eating habits, such as increased hunger or lack of appetite

- Changes in sex drive

- Hallucinations, which means sensing things that don’t exist in reality

- Lack of insight, which is the inability to perceive changes in one’s own feelings, behavior, or personality

- Misuse of substances like alcohol, drugs, or prescription medications

- Multiple physical ailments without obvious causes (such as headaches, stomachaches, or vague and ongoing “aches and pains”)

- Thoughts of suicide (suicidal ideation)

- Inability to carry out daily activities or handle daily problems and stress

- Intense fear of weight gain or being overly concerned with appearance

Mental health conditions can also be present in young children. Because children are still learning how to identify and talk about thoughts and emotions, their recognizable symptoms are often behaviors or complaints of physical symptoms (such as a stomachache or headache). Behavioral symptoms in children can include the following:

- Changes in school performance

- Excessive worry or anxiety

- Hyperactive behavior

- Frequent nightmares

- Frequent disobedience or aggression

- Frequent temper tantrums

View a supplementary YouTube video[13] about warning signs of mental health conditions: 10 Common Warning Signs of a Mental Health Condition.

Causes of Mental Illness

Mental health researchers explain the causes of mental health disorders with several theories. Several factors can combine to trigger a mental health disorder, including environmental, biological, and genetic factors.

Environmental Factors

Individuals are affected by broad social and cultural factors, as well as by unique personal factors. Conditions referred to as social determinants of health (SDOH) can impact the likelihood and severity of developing mental health disorders due to factors such as economic stability, the social and physical conditions where people live, and the ability to access quality health care. For example, unemployment, food insecurity, unsafe neighborhoods, and lack of access to health care can lead to increased psychological distress. See Figure 5.2[14] for an illustration of SDOH.

Adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) such as abuse, neglect, or growing up in a household with substance misuse, mental illness, suicidal thoughts and behavior, divorce or separation, incarceration, or intimate partner violence or domestic violence can affect mental health and are linked to chronic health problems, mental illness, and substance misuse in adulthood. Most adults in the United States have at least one ACE. People who experienced at least four ACEs are more likely to have lower educational attainment and unemployment. Preventing ACEs could reduce the incidence of chronic health conditions, risky behaviors such as smoking and drinking excessively, and socioeconomic challenges. The CDC recommends prevention strategies such as economic support for families, education on healthy parenting and emotion management skills, high-quality childcare and preschool education, education on healthy relationships, connecting youths to caring adults, and early detection and treatment of health issues, along with trauma-informed care.[15] Trauma-informed care is further discussed in one of the following subsections.

See Figure 5.3[16] for an image of adverse childhood experiences.

Take the Adverse Childhood Experiences PDF Questionnaire for Adults to better understand how previous experiences can affect one’s health and feelings of well-being.

Read more information about ACE on the CDC web page: Preventing Adverse Childhood Experiences.

Biological Factors

In addition to environmental factors, biological factors such as neurotransmitters, physiological or infectious conditions, and genetics can affect a person’s mental health.

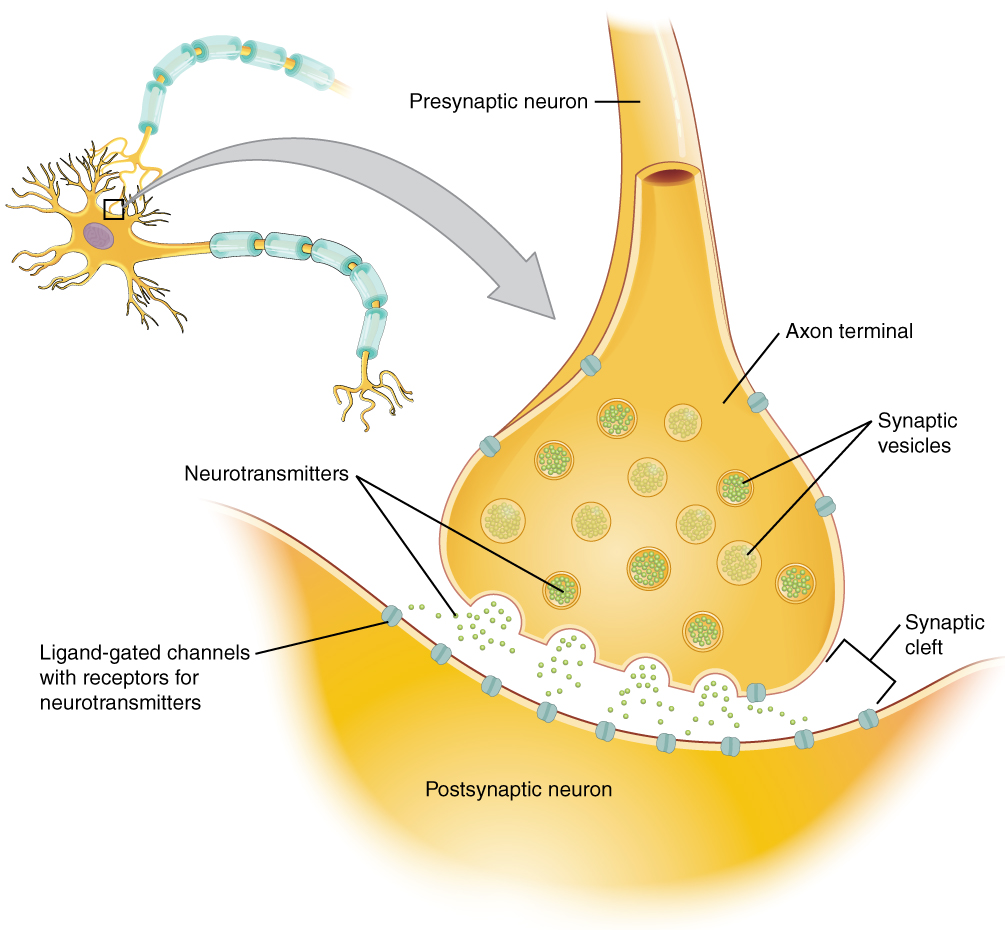

Neurotransmitters

Neurotransmitters are chemicals in the brain that send messages throughout the nervous system. When neurotransmitters and receptors are out of balance, mental health disorders can occur. See Figure 5.4[17] for an illustration of neurotransmitters at the synapse level of the nervous system.

Scientists believe that an imbalance of neurotransmitters, such as dopamine, acetylcholine, gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA), norepinephrine, glutamate, and/or serotonin can cause changes in behavior, mood, and thought. While causes of fluctuations in brain chemicals aren’t fully understood, contributing factors can include physical illness, hormonal changes, reactions to medication, substance misuse, diet, and stress. Many classes of psychotropic medications have been developed to restore the balance of a variety of neurotransmitters.

View a supplementary YouTube video[18] on causes of mental health conditions: Biology of Mental Health Conditions.

Physiological or Infectious Conditions

Mental health can be affected by other physical or infectious conditions. Some studies suggest depressive and bipolar disorders are accompanied by immune system dysregulation and inflammation.[19]

Other research has shown that children may develop obsessive compulsive disorder (OCD) symptoms following a streptococcal infection, referred to as pediatric autoimmune neuropsychiatric disorders associated with streptococcal infections (PANDAS).

Prior to making a mental health diagnosis, health care providers rule out possible physiological causes for symptoms. For example, depression and other mood disorders could be associated with the following physiological conditions:

- Hypothyroidism or hyperthyroidism

- Degenerative neurological conditions, such as multiple sclerosis, Parkinson’s disease, Alzheimer’s disease, and Huntington’s disease

- Cerebrovascular accidents (i.e., strokes)

- Some nutritional deficiencies, such as a lack of vitamin B12

- Endocrine disorders with the parathyroid or adrenal glands

- Immune system diseases, such as lupus

- Some viruses, such as mononucleosis, hepatitis, and HIV

- Cancer

- Erectile dysfunction in men

- Steroid or certain blood pressure medications

Genetics

Some mental illnesses may have a genetic component. For example, individuals with major depressive disorder often have parents or other close relatives with the same illness.

Therapeutic Nurse-Client Relationship

In psychiatric care, the therapeutic relationship is considered to be the foundation of client care and healing. Although nurse generalists are not expected to perform advanced psychiatric interventions, all nurses are expected to engage in compassionate, supportive relationships with their clients using therapeutic communication. The therapeutic nurse-client relationship establishes trust and rapport with a specific purpose of engaging the client in decision-making regarding their plan of care.

Promoting Respect and Dignity

Individuals with mental health conditions and substance use disorders should be treated by health professionals with respect and dignity. Nurses advocate for clients with mental health and substance use disorders and support them, their family members, and their loved ones in an inclusive and equitable manner. The following are tips discussed in the WHO Mental Health Intervention Guide.

Do:

- Treat people with mental health and substance use conditions with respect and dignity.

- Protect confidentiality.

- Ensure privacy.

- Provide access to information and explain the proposed treatment risks and benefits in writing when possible.

- Make sure clients provide consent to treatment.

- Promote autonomy and independent living in the community.

- Provide access to decision-making options.

Don’t:

- Discriminate against people with mental health and substance use conditions.

- Ignore individual preferences.

- Make decisions for or on behalf of individuals.

- Use overly technical language when explaining proposed treatment.

Nurses advocate for clients through cultural awareness. To overcome systemic barriers that can contribute to health disparities, nurses must recognize and respect cultural differences of diverse populations and develop prevention programs and interventions in ways that ensure members of these populations benefit from their efforts.

Using effective communication skills promotes quality mental health care. Tips for effective communication from the WHO Mental Health Intervention Guide include the following:

- Create an environment that facilitates open communication.

- Meet the person in a private space, if possible.

- Be welcoming and conduct introductions in a culturally appropriate manner.

- Use culturally appropriate eye contact, body language, and facial expressions that facilitate trust.

- Explain to adults that information discussed during the visit will be kept confidential. (Special considerations regarding “conditional confidentiality” and mandatory reporting for minors are discussed later in the “Mandatory Reporting” subsection.)

- If caregivers are present, suggest speaking with the client alone (except for young children) and obtain consent from the client to share clinical information.

- When interviewing a young person, consider having another person present who identifies with the same gender to maintain feelings of a psychologically safe environment.

- Involve the person.

- Include the client (and with their consent, their caregivers and family members) in all aspects of assessment and management as much as possible.

- Start by listening.

- Actively listen. Be empathic and sensitive. Allow the person to speak without interruption.

- Be patient and ask for clarification of unclear information.

- For children, use language that they can understand.

- Convey that you understand their feelings and situation.

- Be friendly, respectful, and nonjudgmental.

- Be nonjudgmental about an individual’s behaviors and appearances.

- Remain calm and professional.

- Use good verbal communication skills.

- Use simple language. Be clear and concise. Avoid medical terminology only understood by health care professionals.

- Use open-ended statements/questions and other therapeutic communication techniques. For example:

- “Tell me more about what happened.”

- “To clarify, were you at home or a neighbor’s house when this happened?”

- Summarize and repeat key points at the end of the conversation.

- Allow the person to ask questions about the information provided.

- Respond with sensitivity when people disclose traumatic experiences (e.g., sexual assault, violence, or self-harm).

- Thank the person for sharing this sensitive information.

- Show extra sensitivity when discussing difficult topics.

- Remind the person what they tell you will only be shared with the immediate treatment team to provide the best possible care.

- Acknowledge it may have been difficult for the person to disclose the information.

Review therapeutic communication in the “Communicating With Patients” section of the “Communication” chapter of Open RN Nursing Fundamentals, 2e.

Trauma-Informed Care

The health care system is composed of people, both providing and receiving care, who have experienced trauma or abuse. Individuals who have a history of trauma may have intense feelings triggered when engaging with the health care system that stimulate their “fight, flight, or freeze” stress response. This response can affect the client’s ability to interact with health professionals and may impact their ability to adhere to treatment plans. Nurses must understand the potential impact of previous trauma and utilize principles of client-centered, trauma-informed care.

Trauma-informed care (TIC) is an approach that uses a lens of trauma to understand the range of cognitive, emotional, physical, and behavioral symptoms individuals may demonstrate in health care systems. It emphasizes instilling a sense of safety, control, and autonomy in individuals’ lives and health care decisions. The basic goals of TIC are to avoid retraumatization; emphasize survivor strengths and resilience; aid empowerment, healing, and recovery; and promote the development of survivorship skills.

Trauma-Informed Nursing Practice

Nurses can incorporate trauma-informed care by routinely implementing the following practices with all clients:

- Introduce Yourself and Your Role in Every Client Interaction: Clients may recognize you, but they may not remember your role. When a client understands who you are and your role in their care, they feel empowered to be actively engaged in their own care. They also feel less threatened because they know your name and why you are interacting with them. When one party is nameless, there can be an automatic power differential in the interaction.

- Use Open and Nonthreatening Body Positioning: Be aware of your body position when working with clients. Open body language conveys trust and a sense of value. Trauma survivors often feel powerless and trapped. Health care situations can trigger past experiences of lack of control or an inability to escape. Using nonthreatening body positioning helps prevent the threat detection areas of the client’s brain from taking over and helps clients stay regulated. A trauma-informed approach to body position includes attempting to have your body on the same level as the client, often sitting at or below the client. It could also include raising a hospital bed. Additionally, it is important to think about where you and the client are positioned in the room in relation to the door or exit. Both nurse and client should have access to the exit so neither feels trapped.

- Provide Anticipatory Guidance: Verbalize what the client can expect during a visit or procedure or what paperwork will cover. Knowing what to expect can reassure clients even if it is something that may cause discomfort. Past trauma is often associated with unexpected and unpredictable events. Knowing what to expect reduces the opportunity for surprises and activation of the sympathetic nervous system (SNS) symptoms. It also helps clients feel more empowered in the care planning process.

- Ask Before Touching: For many trauma survivors, inappropriate or unpleasant touch was part of a traumatic experience. Touch, even when appropriate and necessary for providing care, can trigger a “fight, flight, or freeze” response and bring up difficult feelings or memories. This may lead to the individual experiencing increased anxiety and activation of the stress response. Nurses are often required to touch clients, and sometimes this touch occurs in sensitive areas. Any touch can be interpreted as unwanted or threatening, so it is important to ask all clients’ permission to touch them. Asking permission before you touch clients gives them a choice and empowers them to have control over their body and physical space. Be alert to nonverbal signs such as eye tearing, flinching, shrinking away, or other body language indicating the person is feeling uncomfortable. If the client exhibits signs of discomfort when being touched, additional nursing interventions can be implemented such as a mindfulness or grounding practice. (See the “Stress and Coping” section of this chapter for more information.)

- Protect Client Privacy: Family members and other members of the medical team may be present when you care for a client. Clients may not feel empowered or safe in asking others to step out. It is the nurse’s role to ask the client (in private) whom they would like to be present during care and ask others to leave the room.

- Provide Clear and Consistent Messaging About Services and Roles: Trust is built when clients experience care providers who are forthright and honest. Dependability, reliability, and consistency are important when working with trauma survivors because previous trauma was often unexpected or unpredictable. Providing consistency from the nursing team regarding expectations and/or hospital rules can help clients feel secure and decrease opportunities for unmet expectations that might lead to triggering disruptive behavior.

- Use Plain Language and Teach Back: Avoid medical jargon and use clear, simple language. When clients are feeling triggered (i.e., their “fight, flight, or freeze” system is engaged), information processing and learning parts of the brain do not function optimally, and it is hard to remember new information. When providing education, information, or instructions, break information into small chunks and check for understanding. Offer to write important details down so they can accurately recall the information at a later time. Use clear language and “teach back” methods that empower clients with knowledge and understanding about their care.

- Practice Universal Precaution: Universal precaution means providing TIC to all clients regardless of a trauma history.

Crisis and Crisis Intervention

Nurses are often the frontline care providers when an individual experiences a crisis, so it is vital to recognize signs of crisis and intervene appropriately.

A crisis can be broadly defined as a person’s inability to cope or adapt to a stressor, in which their usual coping mechanisms fail. A crisis commonly occurs when an individual experiences a significant life event, resulting in feelings of distress and an impaired ability to function related to their usual daily activities. Examples of such events are a newly diagnosed critical or life-altering illness like a life-threatening myocardial infarction or cancer. Other events that may result in crisis development include stressors such as the loss of a job, loss of one’s home, divorce, or death of a loved one. Clustering of multiple events can also cause stressors to build sequentially so that individuals can no longer successfully adapt and cope, resulting in crisis. Additionally, the crisis may be experienced by family and loved ones of the client.

Nurses assess for signs of crisis and implement strategies to promote safety and effective coping. Signs of crisis include the following:

- Escalating anxiety

- Denial

- Confusion or disordered thinking

- Anger and hostility

- Helplessness and withdrawal

- Inefficiency

- Hopelessness and depression

- Rapid heart rate, rapid breathing

- Pacing

When a client is experiencing a crisis, nurses identify their needs and offer support, including resources for enhanced coping. A variety of factors influence an individual’s ability to resolve a crisis and return to equilibrium, such as realistic perception of the event, adequate situational support, and effective coping strategies to respond to a problem. Crisis intervention refers to resources and interventions to therapeutically assist an individual in crisis to remain safe, as well as ensure the safety of staff, other clients, and visitors. Table 5.1 describes sample therapeutic communication for individuals in early stages of crisis. While implementing these techniques, it is important to act calm and listen to the client’s concerns. Be aware of your nonverbal messages and control your body movements to appear nonthreatening.

Table 5.1. Therapeutic Interventions for Individuals in Early Stages of Crisis[20]

| Strategies | Examples |

|---|---|

| Use therapeutic communication to defuse the stress response and encourage the person to express their thoughts and concerns. | “I understand how hard this must be for you.”

“You seem upset. Tell me more about what is bothering you.” |

| Use a shared problem-solving approach. Avoid being defensive. | “I understand your feelings of frustration. How can we correct this problem?” |

A person experiencing an elevated phase of crisis is not likely to be in control of their emotions, cognitive processes, or behavior. It is important to give them space, so they don’t feel trapped. Many times, these individuals are not responsive to verbal intervention and are solely focused on their own fear, anger, frustration, or despair.[21]

Read more information about additional verbal de-escalation techniques in the “Workplace Violence” section of the “Maladaptive Coping Behaviors” chapter.

If there is no immediate danger, the nurse should notify the person’s psychiatrist, psychiatric-mental health nurse specialist, therapist, case manager, social worker, or family physician who is familiar with the person’s history. The professional can assess the situation and provide guidance, such as scheduling an appointment or admitting the person to the hospital.

If the situation continues to escalate and you can’t reach anyone for assistance, consider calling your county mental health crisis unit, crisis response team, or other similar contacts. If the situation is life-threatening or if serious property damage is occurring, call 911 and ask for immediate assistance. When you call 911, tell them someone is experiencing a mental health crisis and explain the nature of the emergency, your relationship to the person in crisis, and whether there are weapons involved. Ask the 911 operator to send someone trained to work with people with mental illnesses such as a crisis intervention training (CIT) officer.[22]

A person who is severely agitated and out of control may require physical or chemical restraints to be safe. Nurses must be aware of agency policies and procedures regarding restraints if the client’s or others’ safety is in jeopardy.

Review information and guidelines for behavioral restraints in the “Restraints” section of the “Safety” chapter in Open RN Nursing Fundamentals, 2e.

Clients with mental illness and their loved ones should be provided information for what to do if they are experiencing a crisis. Navigating a Mental Health Crisis: A NAMI Resource Guide for Those Experiencing a Mental Health Emergency provides important, potentially life-saving information for people experiencing mental health crises and their loved ones. It outlines what can contribute to a crisis, warning signs that a crisis is emerging, strategies to help de-escalate a crisis, and available resources.[23]

Read NAMI’s Navigating a Mental Health Crisis: A NAMI Resource Guide for Those Experiencing a Mental Health Emergency.

Ethical and Legal Considerations in Mental Health Care

The Code of Ethics for Nurses With Interpretive Statements states the nurse promotes, advocates for, and protects the rights, health, and safety of the client.[24] Ethical principles are used to define right from wrong action. Although there are many ethical principles that guide nursing practice for all clients, foundational ethical principles include respect for autonomy (self-determination), beneficence (do good), nonmaleficence (do no harm), justice (fairness), fidelity (keep promises), and veracity (tell the truth).

When individuals with mental health disorders are admitted to a hospital or long-term care treatment facility, they may lose a number of rights we take for granted, such as the ability to come and go, schedule their time, and control their activities of daily living. In many states, clients’ rights associated with inpatient admission to a mental health unit are spelled out in state law. Clients must be specifically informed of their rights as described in the Patient Bill of Rights document.

The Patient Self-Determination Act was passed in 1990 and is considered a landmark law for client rights. This law requires hospitals, skilled nursing facilities, home health agencies, hospice programs, and health maintenance organizations to provide clear written information for clients concerning their legal rights to make health care decisions, including the right to accept or refuse treatment. Informed consent is the fundamental right of an individual to accept or reject health care. Based on the Patient Self-Determination Act, clients have the right to give informed consent before receiving medical treatment, except in emergency situations when imminent harm may occur to themselves or others.

Competency and Guardianship

Competency is a legal term related to the degree of cognitive ability an individual has to make decisions, carry out specific acts, or provide informed consent. Individuals are considered competent until they have been declared incompetent in a formal legal proceeding. If found incompetent, the individual is appointed a legal guardian or representative who is responsible for providing or refusing consent (while considering the individual’s wishes). Guardians are typically family members such as spouses, adult children, or parents. If family members are unavailable or unwilling to serve in this role, the court may appoint a court-trained guardian.[25]

Guardianships and protective orders are legal methods in states for appointing an alternative decision-maker and identifying required services for individuals who are legally incompetent. Legally incompetent individuals may have developmental disabilities, chronic and serious mental illness, severe substance use disorders, or other conditions that limit their decision-making ability. A court can issue orders for a person who has a guardian to be protectively placed. The legal standard basically states that without the protective placement, the individual is so incapable of providing for their own care and well-being that it creates a substantial risk of serious harm to themselves or others. Protective services may include case management, in-home care, nursing services, adult day care, or inpatient treatment. Protective placements must be the least restrictive setting necessary to meet the individual’s needs and must be reviewed annually by the court.[26]

Seclusion and Restraints

Seclusion refers to the confinement of a client in a locked room or an area from which they cannot exit on their own. Seclusion should only be used for the management of violent or self-destructive behavior. Seclusion limits freedom of movement because, although the client is not mechanically restrained, they cannot leave the area.

Restraints are devices used in health care settings to prevent clients from causing harm to themselves or others when alternative interventions are not effective. A restraint is a device, method, or process that is used for the specific purpose of restricting a client’s freedom of movement without the permission of the person. Behavioral restraints are used to manage violent or self-destructive behavior that poses an immediate danger to a client or others. Restraints include mechanical devices such as a tie wrist device, chemical restraints, or seclusion. The Joint Commission defines a chemical restraint as a drug used to manage a client’s behavior, restrict the client’s freedom of movement, or impair the client’s ability to appropriately interact with their surroundings that is not a standard treatment or dosage for the client’s condition.[27] It is important to note that the definition states the medication “is not standard treatment or dosage for the client’s condition.” For example, administering prescribed benzodiazepines as standard treatment to manage the symptoms of a diagnosed mental health disorder is not considered a chemical restraint, but administering benzodiazepines to limit a client’s movement is considered a chemical restraint.

Although restraints are used with the intention to keep a client safe, they impact a client’s psychological safety and dignity and can cause additional safety issues and death. A restrained person has a natural tendency to struggle and try to remove the restraint and can fall or become fatally entangled in the restraint. Furthermore, immobility that results from the use of restraints can cause pressure injuries, contractures, and muscle loss. Restraints take a large emotional toll on the client’s self-esteem and may cause humiliation, fear, and anger.

Any health care facility that accepts Medicare and Medicaid reimbursement must follow federal guidelines for the use of behavioral restraints. These guidelines include the following[28]:

- When applying a restraint that is the only viable option for preventing harm to self or others, it must be discontinued at the earliest possible time.

- A physician or licensed independent practitioner must see and evaluate the need for restraints or seclusion.

- After restraints have been applied, the nurse should follow agency policy for frequent monitoring and regularly changing the client’s position to prevent complications.

- Nurses must ensure the client’s basic needs (e.g., hydration, nutrition, and toileting) are met.

- Range-of-motion exercises and circulatory checks are typically provided hourly. Some agency policies require continuous monitoring or a 1:1 sitter when restraints are applied, or seclusion is implemented.

Review safe use of behavioral restraints in the “Restraints” section of the “Safety” chapter of Open RN Nursing Fundamentals, 2e.

Admission for Care

When clients experiencing severe symptoms of mental health disorders are admitted for inpatient care, their type of admission dictates certain rights and aspects of their treatment plan. Admissions may be voluntary, emergency, or involuntary.

Individuals over age 16 who present to a psychiatric facility and request hospitalization are considered voluntary admissions. Clients admitted under voluntary admission have certain rights that differ from emergency and involuntary admissions. For example, they are considered competent with the capacity to make health care decisions (unless determined otherwise). Therefore, they have the right to refuse treatment, including psychotropic medications, unless they become a danger to themselves or others.[29]

Many states allow individuals to be admitted to psychiatric facilities under emergency admission status when they are deemed likely to harm themselves or others. State laws define the exact procedure for the initial evaluation, possible length of detainment, and treatment provided. During an emergency admission, the client’s right to come and go is restricted, but they have a right to consult with an attorney and prepare for a hearing. Clients may be forced to receive psychotropic medications if they continue to be a danger to themselves or others. However, invasive procedures like electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) are not permitted unless they are ordered by the court or consented to by the client or their legal guardian.[30]

In circumstances when a person becomes so mentally ill they are at risk of hurting themselves or others or become gravely disabled (e.g., unable to provide themselves basic necessities like food, clothing, and shelter) or are in need of treatment but their mental illness prevents voluntary help-seeking behaviors, an involuntary admission for care may become necessary even though the individual does not desire care. The legal procedures are different in each state, but standards for involuntary admission are similar. Because involuntary commitment is a serious matter, there are strict legal protections established by the U.S. Supreme Court. For example, two physicians must certify the individual’s mental health status. Additionally, the client has the right to legal counsel and can take the case to a judge who can order release. If not released, the client can be involuntarily committed for a state-specified number of days with interim court appearances. The court makes a decision based on the “least restrictive alternative” doctrine, meaning the least drastic action is taken to achieve the purpose of care.[31],[32] Nurses must be aware of the state law in which they work regarding involuntary admissions.

Reporting Unsafe or Impaired Professionals

Clients have the right to humane treatment and reasonable protection from harm. For example, if a suicidal client is admitted and left alone with the means of self-harm, the nurse has a duty to protect the client and can be held liable for injuries or death that occur. Nurses also have a duty to protect clients from suspected negligence by a colleague. In many states, nurses have a legal duty to intervene and report risks of harm to clients. This may include reporting concerns to a supervisor, the institution, and/or the state Board of Nursing. For example, nurses must report suspected drug diversion by colleagues because it can impact safe and humane treatment of clients. Read more about reporting unsafe or impaired professionals in the “Substance Misuse” section of the “Maladaptive Behaviors” chapter.

Mandatory Reporting

Another legal consideration for nurses is mandatory reporting. Nurses are classified as mandatory reporters for suspected neglect and abuse of children and vulnerable adults. See the “Mandatory Reporting” subsection in the “Maladaptive Behaviors” chapter for more information on this legal obligation.

- Ernstmeyer, K., & Christman, E. (Eds.). (2022). Nursing: Mental health and community concepts. https://wtcs.pressbooks.pub/nursingmhcc/ ↵

- World Health Organization. (2022). Mental health. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/mental-health-strengthening-our-response ↵

- American Psychological Association. (n.d.). Resilience. https://www.apa.org/topics/resilience ↵

- “continuum.jpg” by University of Michigan is used with permission. Access the original at https://hr.umich.edu/benefits-wellness/health-well-being/mhealthy/faculty-staff-well-being/mental-emotional-health/mental-emotional-health-classes-training-events/online-tutorial-supervisors/section-1-what-you-need-know-about-mental-health-problems-substance-misuse). Used with permission. ↵

- American Psychiatric Association. (n.d.). What is mental illness? https://www.psychiatry.org/patients-families/what-is-mental-illness ↵

- American Psychiatric Association. (n.d.). What is mental illness? https://www.psychiatry.org/patients-families/what-is-mental-illness ↵

- American Psychiatric Association. (n.d.). What is mental illness? https://www.psychiatry.org/patients-families/what-is-mental-illness ↵

- American Psychiatric Association. (n.d.). What is mental illness? https://www.psychiatry.org/patients-families/what-is-mental-illness ↵

- American Psychiatric Association. (2022). Desk reference to the diagnostic criteria from DSM-5-TR (5th ed.). American Psychiatric Association Publishing. ↵

- American Psychiatric Association. (2022). Desk reference to the diagnostic criteria from DSM-5-TR (5th ed.). American Psychiatric Association Publishing. ↵

- American Psychiatric Association. (2022). Desk reference to the diagnostic criteria from DSM-5-TR (5th ed.). American Psychiatric Association Publishing. ↵

- TED. (2017, May 26). There’s no shame in taking care of your mental health | Sangu Delle [Video]. YouTube. All rights reserved. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=BvpmZktlBFs ↵

- NAMI. (2015, February 2). 10 common warning signs of a mental health condition [Video]. YouTube. All rights reserved. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zt4sOjWwV3M ↵

- “Social Determinants of Health” by the Centers of Disease Control and Prevention is in the Public Domain. ↵

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2024). About adverse childhood experiences. https://www.cdc.gov/aces/about/index.html ↵

- “Types of ACEs” by unknown author for Centers for Disease Control and Prevention is licensed in the Public Domain. ↵

- “1225_Chemical_Synapse.jpg” by Young, K. A., Wise, J. A., DeSaix, P., Kruse, D. H., Poe, B., Johnson, E., Johnson, J. E., Korol, O., Betts, J. G., & Womble, M. is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- NAMI Central Texas. (2018, October 17). Biology of mental health conditions [Video]. YouTube. All rights reserved. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=C7P2wWqQE3U ↵

- Ernstmeyer, K., & Christman, E. (Eds.). (2022). Nursing: Mental health and community concepts. https://wtcs.pressbooks.pub/nursingmhcc/ ↵

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (n.d.). The National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health. https://www.cdc.gov/niosh/ ↵

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (n.d.). The National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health. https://www.cdc.gov/niosh/ ↵

- Brister, T. (2018). Navigating a mental health crisis. National Alliance of Mental Illness. https://www.nami.org/support-education/publications-reports/guides/navigating-a-mental-health-crisis/ ↵

- Brister, T. (2018). Navigating a mental health crisis. National Alliance of Mental Illness. https://www.nami.org/support-education/publications-reports/guides/navigating-a-mental-health-crisis/ ↵

- American Nurses Association. (2015). Code of ethics for nurses with interpretive statements. https://www.nursingworld.org/practice-policy/nursing-excellence/ethics/code-of-ethics-for-nurses/ ↵

- Halter, M. D. (2022). Varcarolis’ foundations of psychiatric-mental health nursing (9th ed.). Saunders. ↵

- Brister, T. (2018). Navigating a mental health crisis. National Alliance of Mental Illness. https://www.nami.org/support-education/publications-reports/guides/navigating-a-mental-health-crisis/ ↵

- The Joint Commission. (n.d.). Homepage. https://www.jointcommission.org/ ↵

- Moore, G. P., Moore, M. J., & Im, D. (2024). The acutely agitated or violent adult: Overview, assessment, and nonpharmacologic management. UpToDate. https://www.uptodate.com ↵

- Cady, R. F. (2010). A review of basic patient rights in psychiatric care. JONA’s Healthcare Law, Ethics, and Regulation, 12(4), 117-125. https://doi.org/10.1097/NHL.0b013e3181f4d357 ↵

- Cady, R. F. (2010). A review of basic patient rights in psychiatric care. JONA’s Healthcare Law, Ethics, and Regulation, 12(4), 117-125. https://doi.org/10.1097/NHL.0b013e3181f4d357 ↵

- Cady, R. F. (2010). A review of basic patient rights in psychiatric care. JONA’s Healthcare Law, Ethics, and Regulation, 12(4), 117-125. https://doi.org/10.1097/NHL.0b013e3181f4d357 ↵

- Halter, M. D. (2022). Varcarolis’ foundations of psychiatric-mental health nursing (9th ed.). Saunders. ↵

A state of complete physical, mental, and social well-being and not merely the absence of disease or infirmity.

Refers to an individual successfully adapting to difficult or challenging life experiences through mental, emotional, and behavioral flexibility and adjustment to external and internal demands.

Representation of mental health fluctuation over the course of an individual's life span ranging from well-being to impaited functioning and illness.

A health condition involving changes in emotion, thinking, behavior, or a combination of these, associated with emotional distress and problems functioning in social, work, or family activities.

Used to encompass mental health disorders, psychosocial disabilities, and other mental states with significant distress, impaired functioning, or risk of self-harm.

Abnormal fears.

Refers to thinking about or formulating plans for suicide.

Purposely injuring one’s body, such as cutting oneself with a sharp object.

Sensing things that don’t exist in reality.

The inability to perceive changes in one’s own feelings, behavior, or personality.

The conditions in which people are born, grow, work, live, and age.

Abuse, neglect, or growing up in a household with violence, mental illness, substance misuse, incarceration, or divorce can affect mental health and are linked to chronic health problems, mental illness, and substance misuse in adulthood.

Chemicals in the brain that send messages throughout the nervous system.

An approach that uses a lens of trauma to understand the range of cognitive, emotional, physical, and behavioral symptoms individuals may demonstrate in health care systems.

A person’s inability to cope or adapt to a stressor, in which their usual coping mechanisms fail.

Resources and interventions to therapeutically assist an individual in crisis to remain safe, as well as ensure the safety of staff, other clients, and visitors.

Principles are used to define right from wrong action.

A legal term related to the degree of cognitive ability an individual has to make decisions, carry out specific acts, or provide informed consent.

The confinement of a client in a locked room or an area from which they cannot exit on their own.

Devices used in health care settings to prevent clients from causing harm to themselves or others when alternative interventions are not effective.

Used to manage violent or self-destructive behavior that poses an immediate danger to a client or others.

Drug used to manage a client’s behavior.

Individuals over age 16 who present to a psychiatric facility and request hospitalization.

Individuals admitted when they are deemed likely to harm themselves or others.

Admission to a mental health facility or unit for care that is necessary to prevent harm to the client or others even though the individual does not desire care.